Peter Smith's Blog, page 89

June 10, 2016

Intro to Formal Logic 2?

I’m mulling over a proposal that I write a second edition of my Introduction to Formal Logic, first published thirteen years ago by CUP.

I’m mulling over a proposal that I write a second edition of my Introduction to Formal Logic, first published thirteen years ago by CUP.

I’m tempted. I’m sure I could make a very much better job of it. Though, of course, I’m only too aware of how time consuming it would be to undertake, and I’d also like to crack on e.g. with the Gentle Introduction to category theory (which has been going slowly of late).

If I do write a second edition, I’d like to include chapters on natural deduction (Fitch-style, I think, for user-friendliness). But I wouldn’t want the book to get too unwieldy in length — and CUP wouldn’t let it! — so some stuff would also have to go. But I guess I could put online some of the current content that goes beyond a usual first logic course (e.g. the completeness proofs for trees for PL and QL!). Would that be a win-win solution? — a tighter book, with the stuff on natural deduction some people wanted, but with the “extras” still available for the small number of real enthusiasts?

I haven’t decided yet whether to take up the proposal, let alone how to reshape and add to the text if I do go with it. But any advice and suggestions (either here, or in emails, address at the end of the About page) — especially from those who have used the first edition or indeed, perhaps even better, from those who decided not to use it — will be very gratefully received!

Intro to Formal Logic 2 ?

I’m mulling over a proposal that I write a second edition of my Introduction to Formal Logic, first published thirteen years ago by CUP.

I’m mulling over a proposal that I write a second edition of my Introduction to Formal Logic, first published thirteen years ago by CUP.

I’m tempted. I’m sure I could make a very much better job of it. Though, of course, I’m only too aware of how time consuming it would be to undertake, and I’d also like to crack on e.g. with the Gentle Introduction to category theory (which has been going slowly of late).

If I do write a second edition, I’d like to include chapters on natural deduction (Fitch-style, I think, for user-friendliness). But I wouldn’t want the book to get too unwieldy in length — and CUP wouldn’t let it! — so some stuff would also have to go. But I guess I could put online some of the current content that goes beyond a usual first logic course (e.g. the completeness proofs for trees for PL and QL!). Would that be a win-win solution? — a tighter book, with the stuff on natural deduction some people wanted, but with the “extras” still available for the small number of real enthusiasts?

I haven’t decided yet whether to take up the proposal, let alone how to reshape and add to the text if I do go with it. But any advice and suggestions (either here, or in emails, address at the end of the About page) — especially from those who have used the first edition or indeed, perhaps even better, from those who decided not to use it — will be very gratefully received!

June 9, 2016

The difference a bit of history makes

We keep car and bikes in the garage at the bottom of the garden. The lane there is very rough and ready. It is unclear who owns what and whose responsibility it all is. The potholes make cycling a hazard, and you have to inch a car along rather gingerly. A bit of a pain, we’ve always thought (though actually having a usable garage in central Cambridge is very unusual).

But now we find that the lane is medieval — a broad track used by people going along the river to cross over to Stourbridge Fair, once the largest fair in Europe (and in the sixteenth century, lasting a month).

Which puts the mud and rubble in a whole new light.

June 8, 2016

A Note on Core Logic

Here’s a very short Note on Core Logic — that’s Core Logic in Neil Tennant’s sense — prompted by reading a forthcoming short paper by Joseph Vidal-Rosset which offers what are supposed to be three fatal objections (link to his paper in my Note, which I’m posting as a PDF as it involves proof diagrams). I’m not sure quite where I stand on Tennant’s project: but I really don’t think that Vidal-Rosset gets the measure of it at all. No doubt Tennant himself will reply in due course; but some might find this quick counterblast of interest.

June 5, 2016

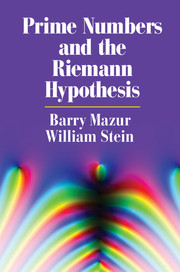

Quick book note: Prime Numbers and the Riemann Hypothesis

Here’s a newly published book from CUP by Barry Mazur and William Stein. It’s delightfully short — just 128 pages before the endnotes, and in fact a fair proportion of those relatively few pages is taken up with graphs and diagrams, and photographs, and there is a lot of white space. The aim is to explain the nature of the Riemann hypothesis and how issues about the distribution of primes relate e.g. to issues in Fourier analysis: there is real mathematics going on here, not just popularising gossip or arm-waving history. The intended readership, at least for the first parts of the book, is beginning mathematics students (or curious amateurs who do have a little maths).

Here’s a newly published book from CUP by Barry Mazur and William Stein. It’s delightfully short — just 128 pages before the endnotes, and in fact a fair proportion of those relatively few pages is taken up with graphs and diagrams, and photographs, and there is a lot of white space. The aim is to explain the nature of the Riemann hypothesis and how issues about the distribution of primes relate e.g. to issues in Fourier analysis: there is real mathematics going on here, not just popularising gossip or arm-waving history. The intended readership, at least for the first parts of the book, is beginning mathematics students (or curious amateurs who do have a little maths).

How well does the book succeed? The headline news: this may in the end be a somewhat bumpier ride than the authors intend — but I indeed found the book very engaging and illuminating. (OK, I know I’m not quite the audience the authors had in mind, but this isn’t maths I’m at all familiar with, so in this area I do count as a pretty naive reader.)

Before giving just a bit more detail, however, I’ll get out of the way a double presentational reservation, namely about the use of photographs. In Chapter 1, for example, we are given a story from Don Quixote that turns on the primeness of 17: cue illustration from a translation of that book. And we are also told the primeness of 17 has something to do with the fact that there are periodic cicadas which emerge every 17 years: cue snap of a cicada. Later when talking about (mathematical) spectra, we get a dull stock photo of a rainbow, and — heavens above! — when talking about the kind of smoothing of data that produces read-outs of average vehicle speed we get a big photo of a car dashboard. Oh dear. These silly illustrations are quite pointless and in fact spoil the aesthetics of an otherwise rather attractively produced book (let the book be judged by the zestfulness and clarity of its expositions, not by false gestures to user-friendliness of this kind). But there’s another reservation, about the other pictures which are portraits. Unlike the popularising books of a familiar kind, we don’t get stories about the lives and eccentricities of past mathematicians: there’s almost no biography here. Yet we do still get unnecessary mug-shots of various mathematicians from Descartes to our contemporaries. Which emphasises all too vividly that those mentioned are — unsurprisingly, given the history — one and all male. Without wanting to come over all politically correct, I wonder whether — in a book trying to enthuse the young — it is a bright idea in this way to unintentionally reinforce once again the impression that maths is a man’s game?

Back to the real content. Prime Numbers and the Riemann Hypothesis is divided into four parts. In Part I, we get an initial statement of the Riemann Hypothesis in the form

For any real number X, the number of prime numbers less than X is approximately Li(X) and this approximation is essentially square root accurate.

Informally, Li(X) is defined as the area of the region under the graph of 1/log(X) from 2 to X, and square root accuracy can be thought of as getting right at least the first half of the digits of the number of prime numbers less than X. Thus explained, this version of the Riemann Hypothesis will therefore be available to any high school student who has met natural logarithms. Lots of computer-generated diagrams are used to make this Hypothesis look a decent bet (though the authors also give warnings about reading too much into such diagrams). And then, if you’ve met the cosine function, you’ll understand the rest of Part One too, with its hints of Fourier analysis. This is all, surely, very well done.

In Part II, we meet “generalized functions” like the Dirac delta function and members of the same family, and get to think rather informally about Fourier transformations of delta functions and the like. So we arrive at the idea of a trigonometric series having an infinite “spike” at various values, and develop the idea of a spectrum of spike values, and learn how to get powers of primes into the story. This requires a bit more more background, and a bit more sophistication, but is still very accessible. Computer-generated diagrams of the behaviour of various truncated trigonometric series are again very effectively deployed in order to underpin plausible hypotheses about what happens in the limit.

Part III is called “The Riemann Spectrum of the Prime Numbers”. I’m not quite sure why the rather short Parts II and III are separated, as it doesn’t seem to require more mathematical sophistication to follow the further exposition here — just a bit more effort, perhaps. With few lapses, this is also clearly and engagingly done. But note, we are still working with those ideas of trig series and Fourier transformations, and haven’t yet met any complex analysis, and hence not yet met the Riemann zeta function. That happens in the very short …

Part IV, “Back to Riemann”, where we begin to connect up the approach of previous chapters with Riemann’s own work. And here the level does indeed ratchet up. It’s not just that you need to at least dimly recall some notions from complex analysis, but the speed of exposition goes up. In fact, I rather wish the space wasted on pointless pictures had been used instead to take things more gently/expansively here and to illuminate more the connection between various versions, announced equivalent, of the Riemann Hypothesis. We are also, along the way, told that RH has lots of interesting implications: again, it would have been good to learn more.

It would also have been good to finish up with a couple of pages or so of an annotated reading list for those enthused enough to want to follow up the discussions (with more pointers, at any rate, than we get in passing on pp. 119-120). After all, Prime Numbers and the Riemann Hypothesis is certainly accessible and intriguing enough to leave many readers wanting to know more.

Overall, then, at least modified rapture! And forgetting the bum notes hit by the photos, we could certainly do with more maths books in this general style.

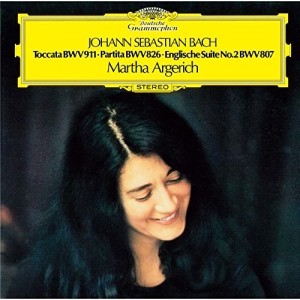

CD choice #6

Time goes so very fast: it is Martha Argerich’s 75th birthday today. Here is perhaps still my favourite recording of hers, from 1980. Completely stunning Bach playing. I can’t put it better than Jessica Duchen has: “Martha Argerich presents intense, minor-key Bach: fierce but pure, finely argued and rhetorical yet never losing the rhythm of dance; expressive but contained and articulated with beautiful clarity. Her intensity is completely compelling from the very first note of the C minor Toccata onwards: she demands, seizes and holds attention at every moment. Her personal vision displays the emotional darkness at the heart of these pieces without any suggestion of mannerism or gimmick.” If you don’t know this disc, you have missed what is surely one of the greatest ever recordings (and it’s now immediately available for streaming if you have an Apple Music, or similar, subscription.)

Time goes so very fast: it is Martha Argerich’s 75th birthday today. Here is perhaps still my favourite recording of hers, from 1980. Completely stunning Bach playing. I can’t put it better than Jessica Duchen has: “Martha Argerich presents intense, minor-key Bach: fierce but pure, finely argued and rhetorical yet never losing the rhythm of dance; expressive but contained and articulated with beautiful clarity. Her intensity is completely compelling from the very first note of the C minor Toccata onwards: she demands, seizes and holds attention at every moment. Her personal vision displays the emotional darkness at the heart of these pieces without any suggestion of mannerism or gimmick.” If you don’t know this disc, you have missed what is surely one of the greatest ever recordings (and it’s now immediately available for streaming if you have an Apple Music, or similar, subscription.)

But oh how we wish that Argerich had recorded more Bach over the years …

June 2, 2016

The English art

We drive to and from Cornwall slowly each year, staying over for a night somewhere, visiting National Trust gardens en route — this year Coughton Court and Killerton as we drove down, Knightshayes and Hidcote on the way back to Cambridge. If the weather is bad we’ll take the tour of a historic house — but they are only shells of the homes they once were, while their grounds are bursting with life and colour in May.

We drive to and from Cornwall slowly each year, staying over for a night somewhere, visiting National Trust gardens en route — this year Coughton Court and Killerton as we drove down, Knightshayes and Hidcote on the way back to Cambridge. If the weather is bad we’ll take the tour of a historic house — but they are only shells of the homes they once were, while their grounds are bursting with life and colour in May.

The making of gardens is surely one of the art forms the English do best, and care about the most.

May 25, 2016

Postcard from Cornwall

In Cornwall again, back in St Mawes. As lovely as before. The photo was taken walking along another little bit of the South West Coastal Path this morning, this time along the cliff-tops between Portloe and Pendower. On the whole, kind weather. Too kind, at any rate, to be sitting indoors, reading much serious stuff: that, and logical blogposts, can wait until I return to Cambridge, far too soon.

May 15, 2016

TYL 2017?

The Teach Yourself Logic 2016 Study Guide is linked here at Logic Matters but also at my (decidedly sparse) academia.edu page. Rather startlingly, the latter link has now been followed up over 50K times. Who knows how much impact the Guide really has. Still, I occasionally get appreciative emails (and equally cheeringly, I don’t get protests from colleagues complaining bitterly that I am leading the youth astray). So, hopefully, TYL 2016 is doing some good in spreading the logical word.

That’s the plus side. The downside is that, given it indeed seems to be used quite a bit, I suppose I should keep on updating the Guide. The year is already rattling by, and I guess I should soon start turning my mind to the time-consuming business of (re)reading around logic books old and new, familiar and less familiar, as background homework for producing TYL 2017. So if you do have suggestions for improvement, and in particular suggestions of recent books I should really take a look at over the next few months, do let me know sooner rather than later.

So many logic books, so little time …

May 11, 2016

Kurt Gödel, Philosopher-Scientist #5

The next paper in Kurt Gödel, Philosopher-Scientist is by Paola Cantù, on “Peano and Gödel”. The headline claim is that Gödel’s philosophical notebooks indicate that he had read Peano (and in particular Peano’s contributions to the Formulaire des mathématiques /Formulario Mathematico) rather carefully — and that Gödel was alert to the important differences too between Peano and Russell.

Unfortunately, when it comes to trying to spell out carefully what Peano’s views were (e.g. about the nature of functions), how Russell’s differed, and exactly what Gödel’s response comes to, I found Cantù less than ideally clear.

Here’s just one example where Cantù seems muddled. Peano defines the “classe nullo”  to be the class of objects which are common to every class (“classe de objecto commune ad omne classe” Formulario, §6). Peano also defines the iota function (Formulario, §7) such that

to be the class of objects which are common to every class (“classe de objecto commune ad omne classe” Formulario, §6). Peano also defines the iota function (Formulario, §7) such that  is the singleton class of

is the singleton class of  (the class of

(the class of  such

such  ). And then he adds a [partially defined] inverse iota function which undoes the effect of the iota function. I can’t typographically invert an iota here, so I’ll follow the later Peano and write

). And then he adds a [partially defined] inverse iota function which undoes the effect of the iota function. I can’t typographically invert an iota here, so I’ll follow the later Peano and write  instead: and then the idea is that, if

instead: and then the idea is that, if  is a class other than

is a class other than  such that any two members of it are equal (i.e. if it is a singleton class), then

such that any two members of it are equal (i.e. if it is a singleton class), then  =

=  iff

iff  . Note, by the way, Peano’s inverted iota is very different from Russell’s!

. Note, by the way, Peano’s inverted iota is very different from Russell’s!

Peano then shows, inter alia, that  where ‘

where ‘ ’ is in fact just one obvious way of characterizing the singleton of

’ is in fact just one obvious way of characterizing the singleton of  . The finer details of ‘

. The finer details of ‘ ‘ don’t matter.

‘ don’t matter.

So far so good. But Cantù comments on the latter rather trivial result as follows:

The definition of

by means of the inverse iota operator allows us to define it as an individual object rather than as a set: nullo is the element associated to a set that contains all the

such that

, i.e. the elements that, for any property, satisfy that property and its contradictory.

This is surely muddled (even forgetting about Cantù’s symbolic foul-up, though that doesn’t inspire confidence).  no more defines

no more defines  as an individual object in any sense that contrasts with being a class than would do the close equivalent

as an individual object in any sense that contrasts with being a class than would do the close equivalent  =

=  !

!  is still a class (though of course, it also an element — an element of its own singleton). Peano’s result which Cantù quotes doesn’t make nullo an element associated to a set containing just those things satisfying some contradictory condition (associated how?); rather it still is, as originally defined, a perfectly respectable class.

is still a class (though of course, it also an element — an element of its own singleton). Peano’s result which Cantù quotes doesn’t make nullo an element associated to a set containing just those things satisfying some contradictory condition (associated how?); rather it still is, as originally defined, a perfectly respectable class.

To move on, there is a quite separate issue for Peano when he later makes use of the inverted iota operation applied to classes defined by conditions not guaranteed to determine singletons. How are we to understand ‘ ’ if

’ if  is not a singleton? Good question. Cantù gives an entry from Max Phil where Gödel (a) holds that Peano commits himself to the idea that there is a contradictory null object (Unding), and “

is not a singleton? Good question. Cantù gives an entry from Max Phil where Gödel (a) holds that Peano commits himself to the idea that there is a contradictory null object (Unding), and “ when

when  has no elements [or] several elements, is this null object”, but (b) Peano can avoid this obscure doctrine. It is not clear, however, that Peano is countenancing a null object in this sense [which is not to be confused with the perfectly good class

has no elements [or] several elements, is this null object”, but (b) Peano can avoid this obscure doctrine. It is not clear, however, that Peano is countenancing a null object in this sense [which is not to be confused with the perfectly good class  !]. Gödel’s alternative isn’t clear either, and Cantù’s discussion of it here is not easy to follow. But I am not minded right now to sit down with more of the Formulario to try to work out what’s going on — fun though it is to decode Peano’s simplified Latin! So for the moment, I’ll have to leave things in this unsatisfactory state.

!]. Gödel’s alternative isn’t clear either, and Cantù’s discussion of it here is not easy to follow. But I am not minded right now to sit down with more of the Formulario to try to work out what’s going on — fun though it is to decode Peano’s simplified Latin! So for the moment, I’ll have to leave things in this unsatisfactory state.