Peter Smith's Blog, page 56

June 24, 2020

The philosophy of what’s what – and acting Shakespeare too

Here is a very nicely done piece about Hugh Mellor written by Tim Crane ten years ago.

As Tim mentions, one of Hugh’s great passions was the theatre (going to plays with friends of course, but also doing stirling work to secure the future of the ADC theatre, and not least, acting himself). Here he writes something about acting, Role-playing on Stage.

The post The philosophy of what’s what – and acting Shakespeare too appeared first on Logic Matters.

June 21, 2020

Hugh Mellor, 1938-2020

Sad news that Hugh Mellor, the kindest and most loyal of friends, died this morning. I knew that he’d been having treatment for a lymphoma — but even so, this was unexpected. Somehow I thought Hugh would always be with us. Argumentative to the last (only a couple of weeks ago he was trying to get me to see the light about conditionals), he was the very model of a straight-talking, clear-thinking philosopher, who always did his readers and disputants the courtesy of making his positions and his arguments absolutely plain. And he had much more of a hinterland than most of us, with a particular love for the theatre (he was still acting until just three or four years ago). I’ll miss him a great deal.

Sad news that Hugh Mellor, the kindest and most loyal of friends, died this morning. I knew that he’d been having treatment for a lymphoma — but even so, this was unexpected. Somehow I thought Hugh would always be with us. Argumentative to the last (only a couple of weeks ago he was trying to get me to see the light about conditionals), he was the very model of a straight-talking, clear-thinking philosopher, who always did his readers and disputants the courtesy of making his positions and his arguments absolutely plain. And he had much more of a hinterland than most of us, with a particular love for the theatre (he was still acting until just three or four years ago). I’ll miss him a great deal.

The post Hugh Mellor, 1938-2020 appeared first on Logic Matters.

June 20, 2020

From a small corner of Cambridge, 8

The wider world beyond our small corner is in no great shape: weeks upon weeks upon weeks of alarming news rather grinds you down, no?

Keeping on keeping on. But some small steps back towards normality for us. It has been good to have been able to go further afield recently. The two nearby National Trust houses — at Wimpole and at Anglesey Abbey — have opened up their grounds again to visitors. We have been walking too at Wandlebury just outside Cambridge, through the woods and out along the Roman Road beyond. So that’s been a delight.

On the last four walks we have seen red kites overhead (one circling very low at Wandlebury). Once upon a time they were so very rare. The British population was just a dozen or so breeding pairs left in the remote mid-Wales hills. And when we lived outside Aberystwyth, we’d sometimes see one or two very slowly flying down the Ystwyth valley as we drove into town, as they went to scavenge on the town rubbish tip by the sea. They were always a magnificent sight. And even now, seeing a kite remains magical.

This week’s lockdown recommendation? It has to be the series of live lunchtime concerts at Wigmore Hall that have been going since the beginning of the month. You can catch up with the streamed performances here. Two that I’ve particularly enjoyed not only hearing but watching again were the concerts by Lucy Crowe and Paul Lewis. So different in their style! Lucy Crowe conjuring up her widely scattered audience and projecting all her usual vivacity, charm and engagement (stunning singing, it goes without saying). Paul Lewis very inward, as if playing for himself (but again it goes without saying, wonderful Schubert in particular). Do watch, if you missed them!

This week’s lockdown recommendation? It has to be the series of live lunchtime concerts at Wigmore Hall that have been going since the beginning of the month. You can catch up with the streamed performances here. Two that I’ve particularly enjoyed not only hearing but watching again were the concerts by Lucy Crowe and Paul Lewis. So different in their style! Lucy Crowe conjuring up her widely scattered audience and projecting all her usual vivacity, charm and engagement (stunning singing, it goes without saying). Paul Lewis very inward, as if playing for himself (but again it goes without saying, wonderful Schubert in particular). Do watch, if you missed them!

The post From a small corner of Cambridge, 8 appeared first on Logic Matters.

June 17, 2020

Hellman and Shapiro on Mathematical Structuralism

CUP are publishing a series of short books (about 100 pages) under the title Cambridge Elements in the Philosophy of Mathematics. The blurb says that the series “provides an extensive overview of the philosophy of mathematics in its many and varied forms. Distinguished authors will provide an up-to-date summary of the results of current research in their fields and give their own take on what they believe are the most significant debates influencing research, drawing original conclusions.” Which sounds ambitious. So far, though, just two Elements have been published, Mathematical Stucturalism (2018) by Geoffrey Hellman and Stewart Shapiro, and A Concise History of Mathematics for Philosophers (2019) by John Stillwell. No further books are yet announced on the web-page for the series.

CUP are publishing a series of short books (about 100 pages) under the title Cambridge Elements in the Philosophy of Mathematics. The blurb says that the series “provides an extensive overview of the philosophy of mathematics in its many and varied forms. Distinguished authors will provide an up-to-date summary of the results of current research in their fields and give their own take on what they believe are the most significant debates influencing research, drawing original conclusions.” Which sounds ambitious. So far, though, just two Elements have been published, Mathematical Stucturalism (2018) by Geoffrey Hellman and Stewart Shapiro, and A Concise History of Mathematics for Philosophers (2019) by John Stillwell. No further books are yet announced on the web-page for the series.

The hyper-active Stillwell has already written a well-known and accessible Mathematics and Its History (3rd edn, 2010) as well as a number of other non-specialist books (alongside his hard-core maths texts). It seems a bit of a failure of imagination for the series editors to ask him to write another history; and to me, the result looks pretty unexciting.

Again, getting Hellman and Shapiro to write on structuralism is hardly adventurous! But I have now read their book. It’s not clear, really, who the intended readership is. The series blurb — “up-to-date summary”, “current research”, “original conclusions” — might suggest a book aimed at e.g. graduate students. But little of the book reaches that sort of level. (One odd feature: we aren’t told who wrote what, even though some of the passages are in the first person and are characteristic of just one of the authors.)

There is a short Introduction giving initial characterizations of some forms of mathematical structuralism, and setting out some questions that we’d want any structuralism to address. Chapter 2 gives Historical Background. This is over twice the length of the next longest chapter; it is nicely done, with a good selection of quotations, and it will provide very helpful reading for undergraduates. Chapter 3 is then on Set-Theoretic Structuralism, the view that “structures are isomorphism types (or representatives thereof) within the set-theoretic hierarchy”. Of course, this won’t in itself give us structuralism for mathematics across the board: the status of set theory itself is left up for grabs. Indeed, on the obvious story “the foundational theory [set theory] is an exception to the theme of structuralism. But, the argument continues, every other branch of mathematics is to be understood in eliminative structuralist terms.” The authors don’t do much, however, to explain why set theory should get this foundational role, or illuminate how this reductionist story squares with the familiar fact that most working mathematicians can get by in cheerful ignorance of set theory, etc. A student could be better pointed to e.g. some of Maddy’s work for a more nuanced account of the role of set theory in mathematics.

Chapter 4 is on Category Theory as a Framework for Mathematical Structuralism. But who is this short chapter addressed to? The philosophy of maths student (at any level) should have some initial grasp on what set theory is about. But most won’t have much clue about what Category Theory might be, and these brisk arm-waving pages are unlikely to help at all. On the other hand, the few who are in the game will be familiar with the usual suggestions from Awodey and others which are gestured to here: for them, there will be no news, certainly no “original conclusions”.

Chapter 5 and 6 discusses Structures as Sui Generis Structuralism (Shapiro-style) and The Modal-Structural Perspective (Hellman-style). Both views have been around well over twenty years, and we are not going to expect any exciting new insights, criticisms or developments — and in under a dozen printed pages for each chapter, we don’t get them. The final Chapter 7 is on Modal Set-Theoretic Structuralism, in particular as developed by Øystein Linnebo. This topic is at least relatively novel and is significantly interesting; but since the authors are nowhere near as good at explaining Linnebo’s approach as that particularly lucid author is, the sufficiently equipped student reader would do a lot better to go to the original paper “The Potential Hierarchy of Sets,” Review of Symbolic Logic (2013).

Which all sounds rather carping. But overall I found this a very disappointing book.

The post Hellman and Shapiro on Mathematical Structuralism appeared first on Logic Matters.

June 11, 2020

New proof theory blog

A new Proof Theory Blog has started up. “The purpose … is to give proof theorists a venue to communicate ideas, works-in-progress, gems, or simply observations that may be relevant to the proof theory community. The hope is that it can eventually evolve into a vibrant forum for proof theoretic discussions and collaboration.” Looks promising.

The post New proof theory blog appeared first on Logic Matters.

June 10, 2020

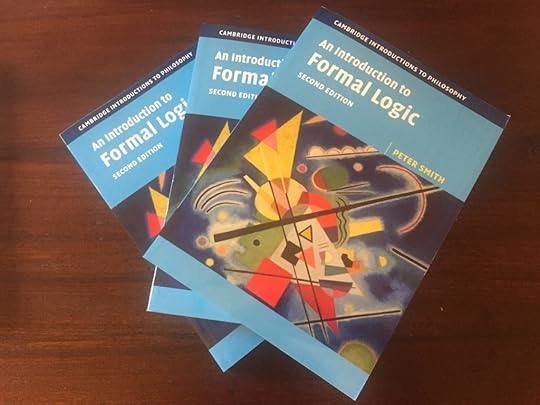

At last, it’s here …!

It’s arrived. Publication date June 25th. Hardback, paperback, PDF version all available. You’ll want all three, of course. Hurry, hurry, while stocks last.

(I’m really pleased with how it looks: so I’ll cut myself some slack and leave fretting about the contents for another day …)

The post At last, it’s here …! appeared first on Logic Matters.

June 8, 2020

Reflections on a pandemic

Click on the banner to explore reflections from CUP authors from various disciplines. They are a mixed bunch indeed, but there are some very interesting and thought provoking ones.

Click on the banner to explore reflections from CUP authors from various disciplines. They are a mixed bunch indeed, but there are some very interesting and thought provoking ones.

The post Reflections on a pandemic appeared first on Logic Matters.

June 2, 2020

IFL2 update … and online lectures?

IFL2 should be published this month. You can admire the cover and “look inside” at an excerpt here, courtesy of CUP (though the first chapter is not particularly representative). There’s more info at the book’s homepage here. I’m gradually populating the page of worked answers to the end-of-chapter exercises. And hey ho, there’s already a corrections page of typos …

I’ve been turning over in my mind the idea of putting online some series of 30 minute lectures associated with the book. At the moment I’m rather minded to provide these as “voice-over-slide-show” videos, probably with some very short talking-head interludes (so the lectures aren’t just coming from a disembodied oracle!). Since you can grow proofs in real time in a video in a way in which you can’t in a printed book, a supplementary series of videos on propositional natural deduction might indeed be quite helpful to students: so that’s where I’d start.

However, delving online for guidance about how best to do this, I’m getting lost! There is a lot of “how to/how not to” advice out there, and it is difficult to know where to start. So if anyone has any recommendations for guidance for similar projects which they have found useful, do please let me know here! [I’d be creating the videos on a Mac, using Beamer for the slides.]

The post IFL2 update … and online lectures? appeared first on Logic Matters.

June 1, 2020

Luca Incurvati’s Conceptions of Set, 15

My comments on Ch. 6 ended inconclusively. But I’ll move on to say just a little about the final chapter of the book, Ch. 7 ‘The Graph Conception’.

Back to the beginning. On the iterative conception, the hierarchy of sets is formed in stages; at each new stage the set of operation is applied to some objects (individuals and/or sets) already available at that stage, and outputs a new object. This conception very naturally leads to the idea that sets can’t be members of themselves (or members of members of themselves, etc.), which in turn naturally gives us the Axiom of Foundation.

But now turn the picture around. Instead of thinking of a set as (so to speak) lassoing already available objects, what if we think top down of a set as like a dataset pointing to some things (zero or more of them)? On this picture, being given a set is like being given a bundle of arrows pointing to objects (via the has as member relation) — and why shouldn’t one of these arrows loop round so that it points to the very object which is its source (so we have a set one of whose members is that set itself)?

Elaborating this idea a bit more, we’ll arrive at what we might call a graph conception of set. Roughly: take a root node with directed edges linking it to zero or more nodes which in turn have further directed edges linking them to nodes, etc. Then this will be a picture showing the membership structure of a pure set with its members and members of members etc. (a terminal node with no arrows out picturing the empty set); and any pure set can be pictured like this. But there is nothing in this conception as yet which rules out edges forming short or long loops. So on this conception, the Axiom of Foundation will fail.

Talking of graphs in this way takes us into the territory of the non-well-founded set theories introduced by Peter Aczel. And these are the focus of Luca’s interesting chapter. I’m not going to go into any real detail here, because much of the chapter is already available as a standalone paper, The Graph Conception of Set, J. Philosophical Logic 2014. But in §7.2, Luca explains — a bit too briskly for some readers, I imagine — Aczel’s four systems. Then in §7.3, he argues that these systems are not mere technical curiosities but arise out of what we’ve just called a graph conception of set: think of sets top down as objects which may have members (as I put it, point to some objects) which may have members etc., and “one can just take sets to be what is depicted by graphs of the appropriate form”. More specifically, in §7.4 Luca argues that the particular anti foundation axiom AFA is very naturally justified on the graph conception. In §7.5, it is argued that some other core set theoretic axioms are equally naturally justified on the graph conception, while Replacement and Choice remain outliers as on the iterative conception.

In the end, then, the claim is that ZFA (ZFC with Foundation replaced by AFA) is as well justified by graph conception as ZFC is justified by the iterative conception. This is among the most original claims in the book, I think, and seems to be to be very well defended. In §§7.6-7.8, Luca fends off some objections to a set theory based on the graph conception, though he argues that the graph conception doesn’t so naturally accommodate impure sets with urelements. But §7.9 then worries that “ultimately, non-well-founded set theory must be justified by appealing to considerations that come from the theory of graphs. Thus, in this sense, non-well-founded set theory is not justificatory autonomous from graph theory. … [I]f set theory is to provide a foundation for mathematics in the sense … endorsed by many a set theorist, the iterative conception fares better than the graph conception.”

Now “faring better” isn’t ”beating hands down”: but Luca will live with that. In the very brief Conclusion which follows Chapter 7, he is open to a “a moderate form of pluralism about conceptions of set, according to which, depending on the goals one has, different conceptions of set might be preferable”. Nonetheless, Luca’s final verdict is conservative: “[W]hen it comes to the concept of set, and if set theory is to be a foundation for mathematics, then the iterative conception fares better than its currently available rivals. This vindicates the centrality of the iterative conception, and the systems it appears to sanction, in set theory and the philosophy of mathematics.”

“We shall not cease from exploration/And the end of all our exploring/Will be to arrive where we started/And know the place …” well, not perhaps for quite the first time, but better than we did! And when I’ve had the chance to think about things a bit more, I’ll edit these blogposts into a single booknote, and may also add some afterthoughts. But I’ve enjoyed reading Conceptions of Set and blogging about it a good deal, and I hope I’ve encouraged some of you to read the book (and all of you to ensure it is in your university library). Congratulations again to Luca!

The post Luca Incurvati’s Conceptions of Set, 15 appeared first on Logic Matters.

May 29, 2020

Luca Incurvati’s Conceptions of Set, 14

We were considering the logical conception of set, according to which a set is the extension of a property. But how are we to understand ‘property’ here? In the last post, I mentioned David Lewis’s well-known theory of properties. If we adopted that theory, which sorts of property would sets the extensions of? The ‘natural’ ones? — no, too few. The ‘abundant’ ones? — too many, it seems, unless we are just to fall back into the combinatorial conception. OK, perhaps Lewis’s isn’t the right choice of a theory of properties! But then what other account of properties gives us a suitable setting for developing a distinctive logical conception of set? Now read on …

Luca does mention the problem just noted about Lewisian abundant properties in his §1.8; but having remarked that this notion of property won’t serve the cause of a logical conception of set, he doesn’t I think offer much guidance about what notion of property will be appropriate. This seems a rather significant gap. (Given a prior conception of sets, we might aim to reverse-engineer a conception of properties such that sets can be treated as extensions of properties so conceived, as in effect Lewis does for his abundant properties: but we are here trying to go in the opposite direction, elucidating a conception of sets in terms of a prior notion of property that will surely itself need some clarification.)

Be that as it may. Let’s suppose we have settled on a suitable story about properties (which will presumably be type-disciplined, distinguishing the type of properties of objects from the type of properties of properties from the type of properties of properties of properties, etc.).

Now on the type-theoretic conception of the universe, the types are incommensurable. As Quine pointed out, this is an ontological division. But, at least on an immediate reading, when the types are collapsed [as in NF] this ontological division is removed: properties (of whatever order) are now objects, entities in the first-order domain. Thus, on this reading, NF becomes a theory of [objectified] properties and ∈ becomes a predication relation, by which a property can be predicated of other objects: x ∈ y is to be read as x has property y.

So the idea is that we in particular are to move from (i) a claim attributing a property P to the object a to the derivative type-shifted claim (ii) that a stands in the membership relation to an object (an extension, or as Luca says an objectified property) associated with the property P.

But how tight is the association between a property and this associated object, the objectified property? The rhetoric of “objectification” might well suggest a non-arbitrary correlation between items of different types (as non-arbitrary as another type-shifting correlation, that between an equivalence relation and the objects introduced by an abstraction principle — prescinding from Caesar problems, it is surely not an accident that the equivalence relation is parallel to gives rise by abstraction to directions rather than e.g. numbers). Luca suggests a different sort of comparison: we can think of the introduction of objectified properties as an ontological counterpart of the linguistic process of nominalization, where we go from e.g. the property-ascribing predicate runs to the nominal expression running. This model too suggests some kind of internal connection between a property and its objectification — after all, it isn’t arbitrary that runs goes with running as opposed to e.g. sitting! If we are going to run with this model(!) then there should similarly be a non-arbitrary connection between the property you have when you run and the object that is its objectivization.

A page later, however, we get what seems to be a crashing of the gears. Luca tells us that sets are objectified properties in the sense of proxies for properties — and

a particular association of properties with objects is arbitrary: there is no reason for thinking of an object as a proxy for a certain property rather than another one.

Really? Well, we don’t want to be quibbling about terminology, but it does still seem to me a bit of a stretch to call a mere proxy an objectification (for that surely does still sound like some kind of internal ontological relationship). If I arbitrarily associate the properties of being red, being blue, and being yellow with respectively the numbers 1, 2, and 3 as proxies, aren’t the numbers more like mere labels? And this now suggests a picture introduced by Randall Holmes in motivating NF: a singleton is like a label for its ‘member’ (different objects get different labels), and a set comprising some objects, having their singletons as parts, is thus like a catalogue of these objects. Now, this conception gives rise to the thought that the resulting set-theoretic truths ought to be invariant under permutations of labels (since labellings in forming catalogues are indeed arbitrary). And then we can argue that, with a few extra assumptions in play, the desired permutation-invariance is reflected by NF’s requirement of stratification in its comprehension principle. For some details, see Ch. 8 of Holmes’s book.

Because Luca also makes the association of sets with properties arbitrary, he too wants a similar permutation invariance of the resulting truths about sets, and so he claims he can too use an argument that this invariance will be reflected by an NF-style theory: “The stratification requirement, far from being ad hoc, turns out to be naturally motivated by the idea that sets are objectified properties.” (Luca’s story seems to have less moving parts than Holmes’s, for on the latter story it seems to be important that sets not only have labels as parts but are themselves labelled. I haven’t worked out whether this matters for Luca’s argument from permutation invariance.)

So where does this leave us? Given the linkage just argued for, Luca can call his picture of arbitrary proxies for properties the ‘stratified conception’, and he writes:

If we accept that there is a sensible distinction between a logical and a combinatorial conception of a collection, this opens up the way for regarding the stratified conception as existing alongside the iterative conception. According to this proposal, the sets – the entities that we use in our foundations for mathematics – are provided by the iterative conception. This conception is often taken to be, and certainly can be spelled out as, a combinatorial conception of collection. By contrast, objectified properties – the entities that we use in the process of nominalization – are provided by the stratified conception. This conception is a logical conception of collection. … [If] the stratified conception is best regarded as a conception of objectified properties, i.e. extensions, it seems possible for the NF and NFU collections to exist alongside iterative sets.

I’m not sure the NF-istes would be too happy about this proposal: their usual view is that the NF universe includes the iterative hierarchy as a part — they just believe in more sets that the ZF-istes, more sets of the same ontological kind (i.e. they don’t see themselves as changing the subject, and talking about something different). But let that pass. What you make of all this will depend in part on what you think of this talk of objectified properties as mere arbitrary proxies. Holmes’s talk of sets-as-catalogues-based-on-arbitrary-labelling does seem a franker version of the same basic conception. Does that make it more or less attractive?

The post Luca Incurvati’s Conceptions of Set, 14 appeared first on Logic Matters.