Peter Smith's Blog, page 131

April 13, 2011

Postcard from the Bahamas

We are staying with Ms Rum'n'Reason and Mr R&R on New Providence — more exactly, we're staying in the north west corner of the island, well away from Nassau where the cruise ships dock. Here, as you can see, the beaches are almost deserted. I've not been a great one for beaches in the past, but these have really converted me. And we've come this time in the ideal month of year, before it gets too humid. Combine that with wonderful food too, courtesy of Ms R&R, and it's all pretty perfect.

We are staying with Ms Rum'n'Reason and Mr R&R on New Providence — more exactly, we're staying in the north west corner of the island, well away from Nassau where the cruise ships dock. Here, as you can see, the beaches are almost deserted. I've not been a great one for beaches in the past, but these have really converted me. And we've come this time in the ideal month of year, before it gets too humid. Combine that with wonderful food too, courtesy of Ms R&R, and it's all pretty perfect.

Long relaxing days, then. A lot of reading, only some of it philosophical fun: e.g. just finishing the latest Kate Atkinson, Started Early, Took My Dog (terrific: warmly recommended). But the real discovery has been a musical one. Ms R&R has the Maria João Pires recording of the Chopin Nocturnes. I listen to a great deal of piano music, but usually stopping around Schubert (by the way, Pires's recording of the impromptus is one of my favourite versions); but this is revelatory — and ideal music for sitting on the verandah as the sun goes down at the end of a Bahamian day.

'Started Early, Took My Dog' … It's been nagging away. I recognize that. But from where? Google to the rescue. But of course.

I started Early – Took my Dog –

And visited the Sea –

The Mermaids in the Basement

Came out to look at me –

…

Resolution: reread Emily Dickinson when I get home

April 11, 2011

TTP, 7. §2.II Snapshot dispositions, correction, fiction

The projectivist's root idea is that a judgement that "X is G", for a predicate G apt for projectivist treatment, is keyed not to a belief that represents X as having a special property but to an appropriate non-cognitive attitude to X. But what does being "keyed" to an attitude amount to? Well, for a start, there should be a basic preparedness to affirm X is G when one has the right attitude. But, as we noted, the projectivist wants to put clear water between his position and that of the crude (strawman?) expressivist for whom the judgement is no more than a "snapshot" evocation of the speaker's current attitudes. So the projectivist will want to complicate the story to allow what Weir calls "correctional practices", where snap judgments are allowed to be corrected in the light of thoughts about the judgements of others and oneself at other times, thoughts about how attitudes might be improved, etc.

Weir is pretty unspecific about how the story about correctional practices is to work out in detail, even in the case of "tasty", which is rather oddly his favourite replacement for "G". Maybe his reticence about the details is not so surprising given his choice of example: for I rather doubt that there are enough by way of correctional practices canonically associated talking about what's "tasty" to makes ideas of "correct judgement" robustly applicable here. But still, I'm willing to go along with Weir's general hope that there are might be other cases where projectivism works, and so (i) can illustrate how anchorage in "snapshot-plus-correctional" practices can be meaning-constituting for "X is G", (ii) without giving the judgement realist truth-conditions, while (iii) imposing enough discipline to make it appropriate to talk of such a judgement being correct/true (at least in a thin enough, non-correspondence sense).

As I said before, I doubt that Weir's discussions will do enough to really help out those philosophers of maths to whom the idea of projectivism is (relatively) new. But in this section he goes on to offer another purported illustration of how we might get a (i)/(ii)/(iii) story to fly, this time in a context which will probably be a lot more familiar to logicians, i.e. the treatment of discourse about fiction.

Thus consider Weir's example 'Dimitry Karamazov has at least two half-brothers' in the context of discussion of Dostoyevsky's book. He suggests (as a first shot at describing the relevant "snapshot dispositions")

It is constitutive of grasp of 'Dimitry Karamazov has at least two half-brothers', in the context of discussion of a given English translation of The Brothers Karamazov, that one sincerely assent (if only 'privately') to the sentence iff one believes that the sentence 'flows from' the translated text.

Here 'flows from' is to be elucidated in turn roughly (again, as a first shot) along the lines of "what experienced readers would, on reflective consideration, judge must form part of the story if it is to make overall sense", and this gives us a role for "correctional practices".

I'm not sure why Weir relativizes to a particular translation, which seems unnecessary; but let that pass. And "must form part [sic] of the story" must mean something like "must belong to any sensible/natural filling out of the story text", which raises more problems which we'll let pass too. But the root idea, at any rate, is that (i) the sketched "snapshot-plus-correctional" story means that that (ii) when we say 'Dimitry Karamazov has at least two half-brothers' we are not representing D.K. or expressing truths about the real world (not even truths about what is written in a certain book), nor indeed expressing truths about some other world (whatever that quite means) but are going in for a different kind of speech-performance, as it were a going-along-with a bit of story-telling. But the framework in which we do this is not subject merely to our creative whim (after all we are not Dostoevsky, who is more entitled to carry on just as he wants!) but is constrained enough for us to be able to talk of (iii) correct and incorrect ways of going along with the story-telling.

I don't myself have decided views about discourse about fiction, and don't know whether this line is a "best buy" (indeed Weir himself raises some issues). But it does serve, I think, to give us a case where it seems that the (i)/(ii)/(iii) schema can be filled out in a prima facie plausible way, without tangling with the special problems of projectivisms. So that's a plus point. The attending minus point, I suppose, is that the more you like this account of the semantics of discourse about fiction, the more tempted you might be to recycle it to serve the ends of a fictionalist account of mathematics. So why does Weir after all prefer "neo-formalism" to a brand of fictionalism? We'll have to see …!

April 9, 2011

TTP, 6. §2.I Projectivism

Suppose we want to claim that some class of sentences that are grammatically like those of straightforwardly fact-stating, representational, belief-expressing discourse actually have a quite different semantic function (and remember, this is going to be Weir's line about mathematical sentences: where a fictionalist error-theorist sees a failed representation, or a kinder fictionalist sees a pseudo-representation made in a fictional mode, Weir is going to argue that mathematics isn't in the business of representation at all). How then might we further explicate this idea of superficially representational claims which in fact have a different role?

One context in which such an idea has been developed and put to work is in the neo-Humean "projectivist" account of morals, modals, and the like, as nowadays particularly associated with Simon Blackburn. The root idea is that a judgement like 'X is good' doesn't express a belief about how the world is with respect to some special property of goodness, but rather a sincere such judgement is keyed to the utterer's attitude of approval of X. NB, it isn't that the judgement is about the attitude; rather that it is semantically appropriate, other things being equal, to assertorically utter the judgment when you have the right attitude. Likewise, 'E is highly probable' doesn't express a belief about the occurrence in the world of a special property of objective chance, but rather a sincere judgement is keyed to the utterer's having a high degree of belief in the occurrence of event E. And so it goes.

But of course, the devil is in the details! The root idea here is equally available to the crudest expressivist: the hard work for the Blackburnian projectivist comes in explaining (a) why, despite the anchoring of the judgements in non-cognitive attitudes, it is still appropriate that they have the logical "look and feel" of cognitive judgements — i.e. can be negated, embedded in conditionals, and the like — and there's related work to be done in explaining (b) why it makes sense to reflect "In my view, X is good, but I could be wrong" and the like. What distinguishes the projectivist from the crude expressivist is the sophisticated way in which he tries to explain (a) and (b).

Weir's §2.I touches on the projectivist's treatment of these matters – but in a way that I expect is going to be far too quick for those philosophers of mathematics (surely most of them!) who aren't already familiar with a particular strand of contemporary debate that's mostly conducted remote from home, in meta-ethics. In particular, Weir's constrast between earlier and later Blackburn, and the role of the idea of non-correspondence truth in his later work, will probably mystify (well, I can't say I found it at all clear or helpful, and I start probably knowing a bit more than many logicians about these things, having Blackburn as a colleague!).

And as well as the discussion going too quickly, Weir's discussion of projectivism is oddly framed. The full title of the section is "Projectivism in the SCW framework", and you'll recall that in his §1.III, the so-called sense/circumstances/world picture is exemplified in the treatment of demonstratives and the story about how the situation represented by an utterance involving "that" is co-determined by the literal meaning (or sense) of the utterance and the relevant circumstances of utterance which make a particular thing appropriately salient. But that was a story about context sensitivity in fixing what state of affairs was being represented (it is still good old-fashioned representation that is going on). The new issues raised by projectivist stories about non-representational content seem, then, to be quite orthogonal to the issues about how we need to tweak Fregean semantics to cope with demonstratives.

OK: we have a story about what is happening in the use of sentences with demonstratives and another story about sentences with "good" or "probable" (or whatever else invites projectivist treatment), and in each case the story deploys concepts (salience, pro-attitudes, degrees of belief) which are not part of the thought expressed in the circumstances. But there the similarity surely ends. Needing circumstances to help fix what is being represented is one thing; going in for non-representational thinking is surely something else, about which we need a quite different sort of story than is provided within the confines of the SCW framework as introduced in §1.III.

Still, let's agree that Weir's (over?) brisk remarks serve to point up that there is possibly space for, though also problems attending, treatments of areas of statement-making discourse as non-representational. And that's perhaps all we really need for now, given that Weir has already announced in his Introduction, p. 7, that he doesn't want to offer a projectivist account of mathematical discourse. So let's not get unnecessarily bogged down in worries about how best to develop projectivisms.

Though let me end this instalment with a very small protest about calling projectivism a species of reductionism (rarely a helpful label, of course). Projectivism "populates the world … with certain naturalistically unproblematic attitudes or relations between humans and objects", and in so doing does away with the need to postulate problematic properties of goodness, chance or whatever. So, to be sure, projectivism reduces ontology — but, if we want one word to describe what is happening, we are eliminating the need for the supposedly troublesome non-natural properties.

April 8, 2011

TTP, 5. New readers start here …

So at long last, it's back to discussing Alan Weir's Truth Through Proof (henceforth, TTP). And apologies to Alan, and anyone else, who has been eagerly waiting for further instalments.

Let's quickly, in this post, review where we've got to (cutting-and-pasting a few snippets from previous posts which you've now forgotten!). In his short Introduction, Weir sketches out the ground he wants to occupy. He wants to say that, as a mathematical claim, it is true that are an infinite number of primes. And this common-or-garden mathematical truth isn't to be reconstrued in some fictionalist, structuralist or other way. However, he wants to say, a mathematical claim is one thing, and a claim about how things are in the world is another thing. Speaking mathematically, it is true that there are an infinite number of primes; but there is also a good sense in which THERE ARE NO primes at all.

How is the gap here to be opened up? Not by construing talk of what really EXISTS as a special level of ontological talk, distinct from other talk that aims to represent the world. Rather, the small caps just signal that straightforwardly representational discourse is in play, and the key idea is going to be that mathematical discourse (like e.g. moral discourse) plays a non-representational role — if you like, mathematics makes moves in a different language game.

If Weir is going to be able to develop this line, we'll need to hear more in general about styles of discourse, representational vs non-representational. It's the business, inter alia, of Chap. 2 to provide some of this background. And in the next posts I'll start discussing this chapter. But some semantic groundwork, and some terminology, has already been provided in Chap. 1.

Suppose we aim for a systematic story about how sentences of a certain class get to convey the messages that they do: take, for example, sentences involving a demonstrative 'that'. The systematic story will, perhaps, use a notion like salience, so for example the story tells us that 'that man is clever' expresses a message which is true when the most salient man in the context is clever. Now, for this to be part of a semantic theory that is suitably explanantory of speech-behaviour, speakers will have to reveal appropriate sensitivity to what we theorists would call considerations of salience. But note: those we are interpreting needn't themselves have the concept of salience. So the explanatory account given in our theoretical story doesn't supply a synonym for 'that man is clever': we need to distinguish the literal content of the demonstrative sentence as speakers understand it (what is shared by literal translation, for example) from what we might call the explanatory conditions as delivered by our systematic semantic theory.

It is a familiar and not-too-contentious point that such a distinction needs to be made, and made not just in the case of the semantics of demonstratives. Somewhat unhappily, I'd say, Weir has chosen different terminology to mark it: in particular, he talks not of 'explanatory (truth)-conditions' — which indeed was his initially preferred term — but of metaphysical content. And he says "metaphysical content specifies what makes true and makes false a sentence in a circumstance". This talk of truth-making might suggest that the business of metaphysical content is to specify truth-makers in the sense favoured by some metaphysicians. But not so! Weir in fact is quite sceptical about truth-makers, so understood. Hence we mustn't read more into Weir's terminology than he really intends to put into it: to repeat, so-called metaphysical content is just a specification of the situation where an utterance of the sentence in question would be correct or appropriate or disquotationally-true.

The thought is going to be then that, when it comes to giving the 'metaphysical content' of mathematical claims, the story about what makes a mathematical sentence correct or appropriate or disquotationally-true doesn't mention mathematical entities of a platonist kind but runs on quite different lines. But how? Back in his Introduction, Weir says "The mode of assertion of [mathematical claims] … is formal, not representational". And what does this mean? Well, part of the story is hinted at by the claim that the formal, inside-mathematics, assertion that there are infinitely many primes is rendered correct by "the existence of proofs of strings which express the infinitude of the primes". Hence Weir's "neo-formalism". Our task is going to be that of making sense of this surprising claim, and evaluating it.

Now read on …

April 6, 2011

Huw Price to Cambridge

Good news, I hear as I get online from the Bahamas. Huw Price is definitely coming (back) to Cambridge as the next Bertrand Russell Professor of Philosophy on Simon Blackburn's retirement.

Also the danger that my lectureship would lapse on my retirement seems to have been averted too (despite the financial turmoil which is affecting Cambridge like everywhere). Though it's not so clear yet whether I'll be replaced with someone who can do the necessary logic teaching to keep the logical backbone of the tripos firmly in place. But one battle at a time.

April 1, 2011

Only 46 years late …

Cambridge has its own funny little ways. One example: for decades, if you took Part III of the maths tripos — one of the tougher exams on planet Earth — you got no formal recognition at all, just the glory. Later, until just recently, you were awarded a measly Certificate of Advanced Study.

Actually, I rather liked this quirky refusal to equate Part III with some more humdrum hurdle for which you might get awarded a common-or-garden degree; but the University have decided, at last, to give people who survive the experience a "M.Math.". And moreover, they are doing this retrospectively. So if you passed Part III since 1962 you can now claim your degree, and old hands are particularly invited to do so on April 30th, when there will be a celebration at CMS.

So, a mere 46 years after I worked my socks off, I'm going to turn up in fancy dress to get my gong, and join in the fun. Perhaps an earlier time-slice of me wouldn't have bothered; but now I rather like the symmetry of collecting the degree in my very last term before retirement. And perhaps I'll be slightly ruefully marking some regret too that I didn't stick with the sums.

March 29, 2011

The AHRC and BS again, and again

A remarkable number of people have already signed the online petition to remove "The Big Society" as a strategic area for AHRC funding. If you are an arts UK academic or grad student, you might want to add your name at

and then spread the word among colleagues.

And, if you can bear to read more on this, here's a useful timeline of the debacle, done with wit.

(Added later) For more comment, see James Ladyman's excellent piece in the New Statesman. I found his concluding remarks about the AHRC's bullshit particular congenial, as my own small run-in with them was about the bullshit factor in their sprinkling around descriptions of solid-but-ordinary research (including my own) as "world class". In correspondence, the AHRC apparatchiks seemed quite incapable of seeing why one might worry about this, and I suspected then that this was symptomatic of a more general inability to think and talk straight. I take no great pleasure in finding my unease to have been proved to be well-placed.

(Added still later) The petition already has over 2000 signatures, and growing. For more analysis about why this should have got people exercised, here's more insightful good sense from Iain Pears.

(Later again) Read, too, Stefan Collini on the AHRC and the road to intellectual mediocrity.

The AHRC and B.S. again

A remarkable number of people have already signed the online petition to remove "The Big Society" as a strategic area for AHRC funding. If you are an arts UK academic you might want to add your name at

http://www.ipetitions.com/petition/th...

and then spread the word among colleagues.

March 28, 2011

He that toucheth pitch …

The story so far. The Observer run a piece entitled 'Academic fury over order to study the big society' which starts off

Academics will study the "big society" as a priority, following a deal with the government to secure funding from cuts.

The Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) will spend a "significant" amount of its funding on the prime minister's vision for the country, after a government "clarification" of the Haldane principle – a convention that for 90 years has protected the right of academics to decide where research funds should be spent.

Under the revised principle, research bodies must work to the government's national objectives …

Cue a great deal of angry comment about the dirigiste ambitions of our paymasters (not to mention comparisons with the neo-Stalinist direction of research in the eastern block).

Cue in turn a vigorous if not entirely literate rebuttal from the AHRC:

The Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) unconditionally and absolutely refutes the allegations reported in the Observer … We did NOT receive our funding settlement on condition that we supported the 'Big Society', and we were NOT instructed, pressured or otherwise coerced by BIS or anyone else into support for this initiative.

Ok, suppose that they've not been coerced. Still, they seem to have rather enthusiastically gone along with talk of the Big Society. Far from keeping at arms length from the passing whims of a making-it-up-as-they-go-along government, the AHRC's Delivery Plan 2011-15 repeated refers to the Big Society (you can search the PDF). Thus …

The contribution of AHRC plans to the 'Big Society' agenda are described in section 2 …

In line with the Government's 'Big Society' agenda … the AHRC will continue to support …

And so on. Their website also hosts a document called 'Connected Communities OR "Building the Big Society"' quite explicitly headlining quotes from Cameron.

A spokesman rather pathetically says that the delivery plan had referred to the Big Society 'to help policymakers understand the concept of Connected Communities'. Really? And are we really to believe that the connected communities project would be looking just the same if Labour were still in power?

I've not myself had direct dealings with AHRC apparatchiks (except for a storm in a teacup over some past remarks on this blog, which didn't impress me). But those I know who are closer to such things, at one level or another, have often expressed exasperation or contempt. I've heard few good words. And the recent chatter on facebook and twitter and in comment threads suggests that, very widely, the AHRC is indeed held in pretty low esteem.

Now that might, for all I really know, be all terribly unfair (I've better things to do than spend a lot of time thinking about the AHRC, the REF, and the likes). Maybe the AHRC really are trying to make the best of a bad job, without undue pandering to their political masters. Maybe. Let's be really charitable (humour me!). But still, how can the AHRC apparatchiks not know how very low — unfairly or otherwise — their standing is among the academics whose interests they are supposed to be serve? And if they do know, how can they not have realized that spattering talk about the Big Society through their documents would only serve — unfairly or otherwise — to confirm the prejudices of all those who already are primed to regard them as toadying third-raters with brains addled by management-speak? Only by being politically dim to a rather staggering degree.

Which, even taking the charitable line, doesn't bode too well for us.

PS: I've just noted that the always estimable Iain Pears has added his thoughtful two-pennyworth on all this.

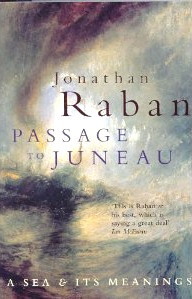

Back to work … and in praise of Jonathan Raban

A surprisingly busy term over. Almost. So, inter alia, I can at last get back to writing my ordinals book and to blogging about Alan Weir's book Truth Through Proof. Watch this space.

A surprisingly busy term over. Almost. So, inter alia, I can at last get back to writing my ordinals book and to blogging about Alan Weir's book Truth Through Proof. Watch this space.

Meanwhile, I've just finished (re)reading Jonathan Raban's quite wonderful Passage to Juneau. If you don't know Raban, you are missing surely one of the very finest living writers of non-fiction prose in English. This is his 1999 book, notionally about sailing his 35ft ketch up the Inside Passage, from his home in Seattle to Juneau in Alaska. But like all good travel books, it is about much more — the voyage of Captain Vancouver that he is retracing, about the original Indian inhabitants and their relationship to the sea, about the idea of the sublime, about the death of his father, about his feelings for his young daughter, about other escapees he encounters at the edge of the world, and much much more. And as ever "journeys hardly ever disclose their true meaning until after — and sometimes years after — they are over". His earlier book Old Glory about a journey by boat down the Mississippi was very fine: but Passage to Juneau is his masterpiece. Read it.