David Kudler's Blog, page 21

May 29, 2013

Apart from Love by Uvi Poznansky released!

Audible has released Stillpoint’s audiobook production of Uvi Poznansky’s contemporary novel of family drama, romance, and intrigue, Apart from Love.

Narrated by David Kudler and Heather Jane Hogan, Poznansky’s novel explores what happens when Ben, a twenty-seven year old student returns home and meets Anita, a plain-spoken, spunky, uneducated redhead, freshly married to Lenny, Ben’s aging father. Behind his back, Ben and Anita find themselves increasingly drawn to each other. They take turns using an old tape recorder to express their most intimate thoughts, not realizing at first that their voices are being captured by him.

Meanwhile, Lenny is trying to keep a secret from both of them: His ex-wife, Ben’s mother, a talented pianist, has been stricken with an early-onset Alzheimer’s. Taking care of her gradually weighs him down. What emerges in these characters is a struggle, a desperate, daring struggle to find a path out of conflicts, out of isolation, from guilt to forgiveness.

Download: apart-from-love-sample.mp3

Apart from Love

May 24, 2013

The Forgotten Branch: Author Jack Beritzhoff Remembers the Merchant Marine

As we approach Memorial Day, most Americans are conscious of honoring those who have served in the military, so it isn’t surprising that nearly all of us could name the three largest branches of the armed services — the Army, the Air Force, and the Navy (of which the Marines are the land troops). Quite a few of us could add the Coast Guard to that list.

Very few, however, would think to include the Merchant Marine, what Jack Beritzhoff, former merchant seaman and author of Sail Away: Journeys of a Merchant Seaman, calls “the forgotten branch of the military”:

David Kudler: The forgotten branch?

Jack Beritzhoff: People don’t remember that the Merchant Marine was around before the Navy — during the Revolutionary War, the Colonies hired merchantmen to protect our shores and cargoes. At the height of the Second World War, when I served, there were over 250,000 merchant sailors bringing supplies to American forces and our allies, getting torpedoed by U-boats in the Atlantic and strafed by Japanese planes in the Pacific. There are a lot of historians who say that it was our merchant fleet that won the war as much as anything.

And yet you won’t find many memorials to dead merchant sailors. We weren’t even awarded veteran status until 1987; no GI Bill for us!

David Kudler: How did you end up in the Merchant Marine?

Jack Beritzhoff: When my draft number came up, I went down to the Army recruiting office. I was a skinny boy then, and so they made me 4F, not fit for service. Well, guys didn’t want people to think they were shirking, so I went to the Marines — they turned me down too. The recruiter said, “Son, there’s no way you could carry a pack that weighs more than you!” Then he told me that there was Merchant Marine training school run by the Army out on Catalina Island off of Los Angeles.

David Kudler: Had you ever been to sea?

Jack Beritzhoff: Nope. I grew up in Alameda, right off of the San Francisco Bay, but I’d never been outside the Golden Gate. When it was time to ship out, I was assigned to the USAT Barbara C, which was due to sail out of Fort Mason in San Francisco with a convoy. I got there, and it was this old wooden steam schooner, a coastal freighter carrying a huge load of lumber to deliver across the Pacific in Australia. We sailed out at sunset under the Golden Gate with the rest of these shiny ships — but by the time the sun rose the next morning, we were all alone. We couldn’t keep up with the fleet. For most of that first leg, from San Francisco to Honolulu, I was so sea sick, I would have been just as happy to die. But I knew I had it better than some: no one shooting at me, and if they’d attacked the ship, it wouldn’t have sunk — it was all wood!

David Kudler: Not exactly a glamorous entrance to the war.

Jack Beritzhoff: No. When we pulled into ports like Hawaii, or Pago Pago, or Numea, I’d have these stories going through my head: Dorothy Lamour at Waikiki, or Joan Crawford as Sadie Thompson in Rain, or sailing into a Free French port, seeing the gendarmes and the Foreign Legionnaires, thinking about Beau Geste. But when we finally sailed into Sidney, this wooden 1880s tramp steamer flying an American flag, we passed a ferry, and this school girl leaned over the rail and yelled down to us, “Oi! What war are you fighting in?” [Laughs]

David Kudler: Were you ever actually under fire?

Jack Beritzhoff: No, we were the lucky ones. I figured any Japanese sub or plane who saw us didn’t want to waste the torpedoes. But wherever we went, we came in just after the fighting was over; there was still the stench of death. And in French Caledonia, we sailed into the biggest fleet any of us had ever seen; they were on on their way to invade the Solomon Islands.

The war was always close. One day, as we were ready to leave port, I realized that we were carrying a hold full of wooden crosses. As I wrote in my book, “I need no Memorial Day to awaken the memory of those who remain so solemnly silent beneath those wooden symbols.”

David Kudler: You say you always had these stories going through your head. Were you writing even back then?

Jack Beritzhoff: No — I never even kept a journal. I’ve always regretted that. But I’ve always been a story teller. And so a few years ago, I started writing out some of these tales that have been in my head all of these years. Then, last year, Sail Away came out. Not many people can say they published their first book at 93!

Jack Beritzhoff was born in Alameda, California in 1918. He is a fourth-generation Californian, the descendent of a California pioneer.

Jack served as a member of the United States Merchant Marine from 1942, at the height of World War II, to 1952, at the end of the Korean War.

Since leaving his life at sea on a San Francisco pier over fifty years ago, he has lived in the Bay Area town of Mill Valley. He has three children and three grandchildren. Jack started writing at the age of ninety-one. His first book, Sail Away: Journeys of a Merchant Seaman was published by Stillpoint Digital Press in 2012.

For more information about the United States Merchant Marine, visit the service’s web site, USMM.org

All images copyright © 2012 Jack Beritzhoff except for cemetery image, by Marion Doss, which as used through a Creative Commons license and recruiting poster, used courtesy of US Library of Congress posters collection

May 17, 2013

Spreadsheets to Galleys: How to Budget Your Self-Published Book

After I wrote recently about why self-publishers need to use professional editors, a number of folks emailed and commented, asking just how much such an endeavor would cost. It was a tough question to answer — I know what I would charge for many services, but it’s difficult to say what the market cost might be, especially for services that I myself don’t regularly provide. Understandably, some correspondents were anxious, wondering if they should jump in, not knowing what the whole process might cost.

This week on PBS.org, Miral Sattar, CEO of the publishing-services marketplace site BiblioCrunch, posted what I found to be a quite thorough rundown of what it might cost to put a self-published book through as professional as possible a publishing process.

She posited a fairly typical book, weighing in at around 70,000 words. She made no further stipulations — fiction vs. non-fiction, for example, or thoroughly workshopped, researched, and rewritten vs. hastely pulled together. The style, genre, and initial quality of the prose do make a huge difference in terms of the kind and amount of editorial work that needs to be done, obviously. Ms. Sattar was trying to explore a median case.

She based her standards and pricing on the Editorial Freelancers Association’s posted rate sheet, which is as close to an industry standard as exists.

Here in brief is Sittar’s rundown (each entry has a low and a high end estimate):

Service:

Low-end est.:

High-end est.:

Developmental Editing:

$2,520

$18,200

Copyediting:

$840

$7,000

Cover Design:

$150

$3,500

Ebook & Print Layout:

$0

$2,500

ISBN:

$125

$250+

Distribution:

$0

(% of gross $)

Pre-publication Reviews:

$0

$970+

Marketing/PR:

$100

$5,000+

Totaling that up, Sattar estimates a low-end total cost of $3,735, and a high-end total of $37,420 or more.

That probably made some of you catch your breath.

I would like to speak to some of the assumptions — so don’t hyperventilate just yet.

First of all, commercial publishers spend more than $4000 to bring even the least expensive title to market, and can spend millions at the high end. They’re your competition. Don’t sell yourself short by cutting corners — without a reason.

I will say too that I think all of Sattar’s numbers make sense in and of themselves (with a couple of exceptions). Even so, I’m not sure that, taken together, they necessarily represent a hard-and-fast range.

Let’s examine those points individually:

Developmental editing: This is the biggest portion of the production budget, and for good reason, since without a well-thought-through and well-built foundation, no book will ever have the impact the author is looking for. As Sattar puts it, “Not having an editor is like not QA’ing a software product or not testing a drug before it goes out onto the market.”

Even so, Sattar’s estimates feel a bit high to me for two reasons: first, she added $5/hour to the EFA rates — generous but, in my experience, unrealistic; second, the low-end estimate seems to assume that all manuscripts need a full developmental edit. If the author has been working with a writing group or sharing the manuscript with other experts in the field, that may not be true. I have to say, too, that the high-end number sounds more in line with what I would expect to charge for co-writing (aka ghostwriting) a book rather than editing one.

Copyediting: This felt more accurate — though if a mid-length book needs 140 hours of work (that’s about two pages per hour), I wouldn’t consider that a copy edit; it would mean that I’d be doing a heck of a lot more than just cleaning up the language.

Cover design: Yup. You can potentially find a designer who will toss off a generic cover for even less than $150 with public-domain art — but you’ll get what you pay for. It may be true that you can’t judge a book by its cover, but that doesn’t stop people from doing just that every day. (That said, spending top dollar on a cover for a book that’s still a mess inside probably isn’t going to help you sell many copies either.)

Print and ebook formatting: This was one of the entries that I had the biggest problem with.

Yes, you can indeed convert your manuscript into ebook format using Calibre, Apple’s Pages, OpenOffice, Scrivener, or a service like Smashwords (which uses a stripped-down, older version of Calibre). That doesn’t mean it’s going to look good without some real work. With a book that’s straight prose — a novel, say — containing no images, tables, or any complicated text formatting beyond perhaps chapter heads, that will probably work fine — if you know how lay out a book with all of the parts in the proper order. (A guide like The Chicago Manual of Style can be a real help here.)

If, on the other hand, you want to do anything more complex (like an illustrated book, for example, or poetry, or a scientific or business text that includes charts and tables) or you want to play around with typography (adding drop caps or specific fonts), you are absolutely going to need to spend time tweaking and refining the file. You’ll often need to create multiple versions of the ebook for different formats, since what works on a Kobo or the iOS app iBooks won’t necessarily display the same way on a Nook or on Adobe Digital Editions, and almost certainly won’t on a Kindle (though that’s getting better). You can use Sigil — it’s a wonderful open-source WYSIWYG ePub editor that I use every day — but the learning curve is not inconsiderable.

Unless you know a fair amount about HTML, CSS, and the ePub 2 and 3 formats, you’re going to have to spend quite a while getting the ebook to look the way you want on every device. And then you’re going to have to port the file over to the .mobi/Kindle format, which will require even more tweaking. So don’t forget to budget in your own time. How much is all of that time worth to you? Make the decision of whether to convert yourself or to outsource based on that cost-benefit equation.

Even more than that: unless you really, really know what you are doing do not plan on laying out a print book without professional assistance. There are so many things that can go wrong with creating a print edition — even with the advent of print-on-demand (POD) and easy revision — that planning on taking the low-end path here seems to me a penny-wise-pound-foolish decision. A good book designer — along with a good editor and a good cover designer — can be your best friend.

If you truly don’t want to go to the expense and your book is fairly straight-forward, design-wise, I highly recommend investing in one of the low-cost layouts from Book Design Templates. These templates are pre-designed to allow you to convert your Microsoft Word document into a press-ready file. Will the book win design awards? Probably not — but it will look professional.

Proofreading: This is my other biggest problem with Sattar’s mostly excellent run-down — she left out this essential step in the editorial process. Proofreading happens once the ebook has been designed or the print edition laid out but before it goes to press. New errors can creep in — inadvertent line breaks or deletions, or incorrect headers, for example. The design can create visual problems for the text (rivers, widows, orphans, and other print-design headaches). This is also the last opportunity to clean up any lurking style problems such as misspellings, grammar errors, or improper punctuation.

Proofreaders are special folks: they have eyes for fine detail, and they work fast, so they aren’t terribly expensive. (They’re not supposed to rewrite the text, but rather to make sure that what’s there is what’s supposed to be there.) According to the EFA rate sheet, a proofread of that 70,000-word book (no longer a manuscript!) would run approximately $650–$1100. Plan on spending that — you’ll be glad you did.

Distribution and Printing: Sattar is absolutely right here. There’s no need to spend money on paid distribution (one of my main beefs with publishing “services” like BookBaby), and for most self-published authors it makes no sense to start by incurring the expense of an offset print run.

One exception would be if the book includes high-quality images, which POD won’t generally reproduce well. Another would be if you’ve gone the high-end route with everything else, banking on creating a best-seller. If your business plan for the book assumes that you’re going to sell thousands of copies, you might consider spending the up-front money to print and house them, since the per-copy printing cost will be so much lower. At the very least, it’s an incentive to make sure that you follow through on that plan!

Reviews: Sattar is almost certainly right here as well; it irks me, however, that an independent publisher-author should have to pay to be reviewed. Paid reviews create a huge ethical dilemma — and commercial publishers aren’t forced to jump the same hurdle with the large review services. Also, there is some question whether such reviews are really helpful. (Another, potentially less ethically fraught approach is to use a review distributor like NetGalley, a paid service that offers advance review copies of books to its army of unpaid blogger-subscribers).

Marketing/PR: Again, Sattar is absolutely right. As she says, “This is probably the toughest part after you’ve written the book.” You can do nothing, hoping the book finds readers on its own. You can spend thousands on professional marketing services. As commercial publishers have found over and over again, there’s no sure-fire way to maximize your marketing dollars (though doing nothing and hoping for the best is almost certainly a terrible idea).

Most authors are writing out of passion; it’s a labor of love. I’d argue that this is even more true for authors who want to self-publish.

Yet it is important to remember that publishing a book is also business. That means making the best business decisions that you can — about the words, about the package of the book itself, and about how to market it — in order to have your book find its audience and have the affect them that you are looking for. Making those decisions in a vacuum is never a good idea – it’s too easy to waste time when you should have spent money or throw away money when a little time and effort would have done far more good. Hopefully this has helped you to approach these decisions a bit better prepared.

Image: “New Year, New Spreadsheets” by SaraE @ flickr.com. Used under a Creative Commons license.

David Kudler and Stillpoint Digital Press are not affiliated in with any of the sites or services mentioned herein.

May 2, 2013

PSA: Stopping Bullying and Isolation Before They Start

So, I was going to share a post about the lawsuit against Penguin’s Author Solutions subsidiary, but an article my daughter wrote about an organization that she’s been involved with for the past few years just came out, and with it a video that both she and my wife Maura helped to create (heck, I played sound engineer on the voiceovers!).

Beyond Differences is a student-run organization that seeks to change the culture of America’s schools one school at a time, eliminating social isolation that leads to bullying and worse. So today’s post is a public service announcement instead.

I’ll let Julia take it from here:

Be the One on Vimeo

Beyond Differences Event Highlights Fight Against Social Isolationby Julia Kudler, 9th grader at Branson

Social isolation is a growing problem in schools all over the country. For the past two years, I’ve been a member of a teen-driven group called Beyond Differences that addresses this issue head on, working through assemblies, retreats, and ongoing education to change the culture in middle schools and high schools one school at a time. Last Saturday a standing-room crowd of nearly four hundred packed the Mill Valley Community Center as Beyond Differences held its fourth annual event to raise awareness and to help Bay Area families understand how they can help fight this social epidemic.

Action was the theme for this year’s event, which included a family barbecue lunch and a presentation by forty-one students from a dozen different Marin schools. We shared our own stories, and presented different scenarios to illustrate how to be more inclusive and address social isolation and stop bullying before it starts. As teen leaders, we explained Beyond Difference’s exciting new initiative, No One Eats Alone, a program that through a variety of activities encourages kids to connect at lunch and engage with people they may not know. Hall Middle School, Kent Middle School, Davison Middle School and Brandies Hillel Day School ran the first No One Eats Alone pilot programs this year.

We were very lucky to have KTVU-TV’s anchorman Dave Clark as the master of ceremonies. Welcoming all of us, he spoke about how strongly he believes in what we in Beyond Differences are doing. “I am such a big believer in what these kids are doing,” Clark said. “Experts agree that social isolation is the precursor to problems ranging from teen suicide to dropping out to poor performance in school to impaired health, but Beyond Differences is the only organization talking about it.” Marin County Superintendent of School Mary Burke and educator Keith Fleming also spoke passionately about both what Beyond Differences has accomplished, and what remains to be done.

We also screened the world premier of “Be the One,” an incredible new short film by Jordan Raabe, a young Los Angeles filmmaker who grew up in Marin. “Be the One” shows different examples of how kids feel at school, sporting events and even in the library, when they are not included. The film, which involved members of our Teen Board, brought tears to many in the audience. We hope to see it as a lead-in to family film events in the Bay Area this summer.

For more information about Beyond Differences and our upcoming programs, visit beyonddifferences.org

I’ll share my thoughts on independent publishers vs. publishing service providers vs. vanity presses tomorrow!

April 30, 2013

Stillpoint Partners with Sixteen Rivers Press

Sixteen Rivers Press

As National Poetry Month comes to a close, Stillpoint Digital is proud to be able to announce that we are partnering with poetry collective Sixteen Rivers Press. Not only will we create ebooks with them, but Stillpoint will serve as their online store and distributor. 100% of all Sixteen Rivers net sales will be paid to the award-winning collective. It seems appropriate to us, as a company whose name is drawn from a T.S. Eliot poem!

Stillpoint has released five titles as part of its Stillpoint/Verse imprint:

Space/Gap/Interval/Distance by Judy Halebsky

The Stranger Dissolves by Christina Hutchins

Easing into Dark by Jacqueline Kudler

Practice by Dan Bellm

Sacred Precinct by Jacqueline Kudler

April 24, 2013

David Sings the Blues (and Other Classics)

Long Gone Daddies by David Wesley Williams

I’ve just wrapped recording on my second full-length audiobook this month — David Wesley Williams lyrical novel of sex, family, and rock ‘n’ roll, Long Gone Daddies. As I was listening through just now, I realized that there were a lot of similarities between this bluesy book and my most recently completed (and soon-to-be-released) project, Uvi Poznansky’s Apart from Love. Both books dissect tangled, dysfunctional families featuring deeply fractured father-son relationships, each of which is hiding some very important secrets. And music is very much at the heart of each.

For an audiobook narrator/producer, music is both a joy and more than a bit of a challenge. Audiobooks — for the most part — are not meant to include music tracks (Audible and Amazon don’t like them), and so any music must be created purely by the narrator in the character’s voice. When a song is known, that can be great fun; when it’s created by the author, that’s fun too… but can sometimes take your breath away.

Long Gone Daddies concerns three generations of the guitar-slinging Gaunt family. The narrator, Luther, spends the book in search of his heritage — both from his dead grandfather Malcolm and his disappeared father John (his long-gone daddies) and from his own musical roots. The novel literally abounds with song — discussions and descriptions of music from country blues to New York punk, but also actual performances. Some are described narratively, but in a number of cases the song lyrics themselves move the story forward, and so, as a narrator, I was faced with the daunting challenge of creating dozens of musical passages. The author describes the music in succinct detail; occasionally Luther is singing a classic tune, but most often it’s the offspring of his own imagination (or one of his long-gone daddies’). At that point, I — the least musical personal in a musical family — found myself cast in the unexpected role… of songwriter.

Here’s an example. At one point, Luther and his band-mates (and I bet you can’t guess the name of the band!) visit Clarksdale, Mississippi’s Delta Blues Museum. There, Luther imagines a “cutting contest” (a blues smack-off, the precursor of latter-day rap battles) between bluesman Muddy Waters and Elvis Presley:

/

Update Required

To play the media you will need to either update your browser to a recent version or update your Flash plugin.

Well. That was fun!*

The Kaminsky family in Apart from Love also has a musical soul; unfortunately, that soul belonged to the mother, Natasha. Divorced from narrator Ben’s father, she has disappeared, like Luther Gaunt’s progenitors. Where the Gaunts left behind only an old guitar, however, Ben’s mother left behind a beautiful white grand piano. When Ben’s father Lenny decides to remarry his long-time (and much younger) girlfriend Anita, the new Mrs. Kaminsky decides to use her predecessor’s piano as the stage for a dramatic entrance to the wedding reception. The scene is described here in a letter by Ben’s acid-eyed great aunt Hadassa — and you haven’t lived until you’ve heard an aged Jewish lady singing Bryan Adams:

Play

Aunt Hadassa Sings

/

Update Required

To play the media you will need to either update your browser to a recent version or update your Flash plugin.

So. Who knows what the next audiobook will need me to do? I can’t wait to find out!

* Yeah. My Muddy sounds more like Howlin’ Wolf. You try singing like Muddy Waters. I dare you!

April 16, 2013

Stillpoint Poet Jacqueline Kudler Interviewed

Stillpoint Digital Press author Jacqueline Kudler, writer of Sacred Precinct and Easing into Dark, has been interviewed for a new cultural television series, Marin Poets Live!

As a fitting tie-in to National Library Week and National Poetry Month, the Marin County Free Library is launching a new monthly television series in partnership with the Marin Poetry Center, and in collaboration with Community Media Center of Marin.

Marin Poets Live! is presented by Marin County Free Library, and features host Neshama Franklin, who works at the Fairfax Branch Library. The show introduces local Marin poets, and delves into their reasons for writing and the influence that living in Marin has had on their poetry. Neshama is a devoted and deep reader of poetry, and spends time eliciting background from each poet, as well as offering her insights into the poems that each guest reads aloud. The first show will air Thursday, April 11 at 7:30pm on public Comcast channel 26 and ATT channel 99. The monthly show will appear the second Thursday of each month.

“There’s nothing like hearing a poem straight from the poet’s mouth and heart,” says Neshama. “In person, as viewers will discover, poetry out loud can sing!”

The show’s first guest is Jackie Kudler, a member of the Marin Poetry Center and a founding member of Sixteen Rivers Press.

The funding for this project was generated by a benefit poetry reading that Kay Ryan, twice Poet Laureate, generously did for MCFL. Marin Poets Live! advances MCFL’s goal of promoting local poetry and expanding the visibility of local poets . Current funding of the project is accomplished in partnership with Marin County Library Foundation. Archived episodes of the show will be available for viewing at the library’s website, www.marinlibrary.org. A special page will include the episode, a biography of the poet, and links to books held in the library’s collection.

For more information about this program, and other Marin County Free Library programs, visit www.marinlibrary.org, or email info@marinlibrary.org.

April 12, 2013

In Which David Is Transported….

to Holland, and to Poetry-land, wherever that may be!

First, in a very new experience for me, I found that my article on editing, which went a bit viral on Huffington Post, has been translated into Dutch.

Wow.

Go, internet!

Second, in another first, Uvi Poznansky, who wrote the recently-released Stillpoint audiobook A Favorite Son (and whose audiobook for Apart from Love I’ve just finished editing — woohoo!) wrote a… um… poem about me.

Now, my mom’s a poet (and I’ll have more to say on that subject another time), so I’ve shown up in poems before before. Still. None (so far as I know) about me. This was incredibly touching. Here’s the poem, if you’d like to read it:

April 4, 2013

Behind the Scenes: How to Become Young Again (in an Audiobook)

Uvi Poznansky posted what I thought was a really interesting article about a part of our process in putting together the audiobook for A Favorite Son.

Every book has its own challenges — to the writer, to the editor, and to the audiobook producer. In A Favorite Son, Uvi told a story from a single point of view, but in two separate timeframes: first, of Yonkle (Jacob) as an old man, talking to his own eldest son, Reuben, which was told in the past tense; and second, of young Jacob, as he confronts first his brother Esav (Esau) and then his father Isaac.

As always, I had a blast creating the two distinct-yet-related voices (as well as voices for Esav the Hunter and the other characters). The challenge that Uvi and I worked on was how to meld the two — how to create transitions that made it clear what was happening. I’ll let Uvi narrate the process:

Behind the Scenes Look: How To Become Young Again

When I sculpt a figure, such as here, in one of my earliest pieces, I let it age and become young again, adding and reducing wrinkles as the piece is being formed. For me, working on the audiobook of A Favorite Son is no different, and let me tell you why…

My work was lucky enough to attract the attention of an amazingly gifted voice actor, David Kudler. He is a man of a thousand voices. He says, ”It’s nice to let them out of my head from time to time.” This story provides a great challenge for him, because it starts in the voice of Old Jacob, then as he plunges into the depth of his memories about a crime he committed in his youth, it continues in the voice of the young Jacob. Listen to ‘take 1′:

Oy! Your browser is not compatible with the HTML5 audio tag. Click here to listen to the sample

Problem is, the transition between the two voices, the old and the young. Because it happens ‘turning on a dime’, the listener may think that a new character has just stepped onto the scene. So, here is a different transition, where the voice of old Jacob trails off to a whisper, at the same time that the voice of young Jacob comes in from a whisper to full volume. Listen to ‘Take 2:

Oy! Your browser is not compatible with the HTML5 audio tag. Click here to listen to the sample

Maybe I’m too picky, but I felt uneasy with ‘take 2′. I figured, it is crucial we arrive at a good solution, one that does not jar the ear, one that invites the listener to the journey, so she takes a plunge into the past or rises out of it into the present, together with the character. It is also crucial because we will have more transitions coming up in the next three chapters of the book, so the same solution will apply. It will, in fact, become an audio motive of sorts.

What i envisioned in my mind was this: with no technological ‘gimmick’ (such as the double track of voices in ‘Take 2′), David will start the transition being old, and gradually, word by word, become young! This may be a great acting challenge, because all the listener has to go on is your voice–there is no visual clue such as the incredible hulk changing color to green, and bursting out of a body of a small little guy, whose clothes hang in tatters by the end of the transition. Take a listen to ‘take 3′, which is the final take, and let me know what you think:

Oy! Your browser is not compatible with the HTML5 audio tag. Click here to listen to the sample

I agree with Uvi: I think we made the right choice. What do you think?

Sometimes, the human machine is the best technology there is.

★ New! Get the paperback edition

A Favorite Son

★ New! Get the audiobook edition:

April 2, 2013

Seven Deadly Myths and Three Inspired Truths About Book Editing

I originally wrote this as a guest post for Joel Friedlander’s wonderful self-publishing resource site TheBookDesigner.com; it sparked a lot of great conversation and feedback, and it occurred to me that the information might be of interest to a more general readership. If you’ve ever groaned at typos, continuity errors, plot holes or just plain bad writing in a book or blog post, here’s my prescription:

I’ve edited lots of books — children’s books, fantasy, memoirs, self-help, textbooks, and especially books about myths. Myths? I like myths. Heck, I love myths — if we’re talking about myths as “great poems, [that] point infallibly through things and events to the ubiquity of a presence or eternity that is whole and entire in each.”*

If we’re talking about myths in the more negative sense of “untruths,” however, I like them less — especially if they’re myths about my profession and vocation.

Myths and Misinformation about the Editing of Books

There’s a lot of misinformation and misunderstanding about editors and what they do. Here are seven of those myths that I’d like to clean up:

Myth #1: A good writer doesn’t need an editor.

In these days of self-publication and “service” publishers — who take a percentage of sales for letting the author do all of the work — you hear this a lot. “I’ve slaved over this manuscript for years. I checked it through a hundred times. Microsoft Word’s Spelling and Grammar comes up clean. It’s ready for publication.”

Want an example of a professional book from a world-class author who convinced her publishers to put out the book as-is, without a deep developmental edit (see #3 below)? Look at J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix. Pretty good book, and it’s sold millions of copies, absolutely — but it’s at least a hundred pages longer than it needs to be. There’s needless repetition, uneven pacing, and side-plots that go nowhere. You’ll notice that the previous and subsequent books in the bestselling series were much shorter and much tighter. Rowling worked more closely with her editors.

Here’s the fact: if you want your book to be strong, clean, professional, and appealing, for it to affect the readers as you want it to affect them, you need to have it professionally edited. There’s never been a text written that didn’t need editing. By the time you’ve spent weeks, months, or years on a project, you can’t see the words any more. You can see the ideas — the concepts, arguments, plot, and characters — but not every word that’s on the page, or that isn’t, or where there are gaping holes in logic or jumps in style. An editor will. It’s what they’re paid to do.

Myth #2: I don’t need the expense of paying an editor. I had my wife/dad/neighbor/high-school English teacher read it through, and they didn’t find anything.

There’s no doubt that the more eyes you run your manuscript past the better. Those readers know you and love you; that’s a wonderful thing, but it’s a disadvantage as well.

A professional editor’s primary connection to the book is the manuscript itself. Your friends are all going to give you wonderful support and advice (especially that English teacher, for whom I hope you made cookies), but they’re not going to approach the text with the kind of eye for detail that an editor brings.

Myth #3: All editors are the same.

No. There are a variety of editing tasks that need to be addressed as a book goes through the publishing process, each of which requires a different set of skills:

Developmental editors work with the author to craft the manuscript, looking at structure and argument in non-fiction or plot and character in fiction. (In traditional publishing, these are usually the acquiring editors.)

Line or substantive editors also look at the manuscript as a whole, but generally don’t work as closely with the author and aren’t expected to edit as deeply. (This and the previous category are sometimes lumped together as substantive editing.)

Copy editors concentrate on the language or copy. They focus on trying to make the style of the manuscript clean and consistent.

Proofreaders are usually the last folks who look at a book, in galley or proof form, as it’s about to go off to be printed (or, in the case of ebooks, as it’s about to enter distribution). They’re looking purely for misspellings or errors in style, such as improper punctuation, grammar or formatting .

That’s not even to mention the army of other professionals who will probably be needed in order to craft a book out of a manuscript, from layout and cover designers to fact checkers, permissions researchers and the rest.

One editor might provide many of those functions, but not all at once. (See #6 below).

Myth #4: An editor is an editor — so I should just find the cheapest one I can.

It’s your work and your money; you should budget what you can afford in order to create the book that has the impact you’re looking for. As I mentioned above there are different kinds of editors who have different skills, and different kinds of editing demand different commitments of time and energy, so cheap isn’t necessarily better. I’m going to charge a lot more to do a long-term, deep, developmental edit (where I am working with the author to improve the manuscript at the fundamental level) than I will for a simple just-before-publication proofread (where I’m just looking carefully for punctuation, grammar, and style issues).

In addition to marking it up, a good substantive or developmental editor will make lots of queries (questions for the author) on the manuscript, where a copy editor will mostly clean up the language as-is, and a proofreader is usually purely focused on correcting any errors of usage or formatting. These are different approaches to your work.

As with any other service, you get what you pay for.

Myth #5: Okay, fine. I’ll hire an editor. It’s like calling a taxi; take the first one you flag down.

The best way to hire the right editor is probably to talk to any other writers you know and ask for recommendations. You could also look for a local freelance board or service or an online service such as Elance.com. I’d encourage you to look locally first; you don’t need to be able to meet the editor face-to-face, but it doesn’t hurt, especially if it’s a longer-term project.

Get some candidates, tell them exactly how long the manuscript is and what kind of edit you are looking for (see #3 above), and give them a short sample — five to ten pages should do. Ask them to edit it and give you a quote for the whole project, as well as an idea of how long it would take them. You might also ask them if there’s a particular style manual they like to use.

Most likely, no two will edit it exactly the same way, or give you the same quote or time frame. Choose the one you feel did the best job with your prose, asked the most insightful questions, and is within your time and financial limits.

Myth #6: I hired an editor who worked with me for months to rewrite the manuscript. Now it’s ready for publication!

Well… maybe. What I said above about fresh eyes? That holds for editors too. If I’ve been working with an author on a manuscript for a long time, there comes a point where I too become blind to the details.

So if you’ve hired me to do a developmental edit, I may strongly suggest that you work with a copy editor before the book gets laid out — and then, once your magnum opus is in its final format, a proofreader as well.

Myth #7: The editor marked up my manuscript, but I have no idea what the notes are about. Diction? Series commas? The editor is making it up!

Honestly, truly, no. We all cringe instinctively at the sight of our words marked in red, a habit instilled during our school days. But those marks the editor made aren’t criticism. An editor’s first job is to create the best book possible out of your manuscript. You’re paying for the editor’s professional judgment. Welcome it — but if you honestly disagree with or don’t understand a change, let the editor know and ask for the rationale.

The editor should be able to tell you that rationale. He or she was most likely trying to make the prose in your manuscript consistent with a standard. They almost certainly are working with a specific style manual whether it’s The Chicago Manual of Style, The New York Times Manual of Style, The MLA Manual, or even just Strunk and White’s Elements of Style. There should be a dictionary that you can agree on. (I had a problem with an English proofer once who inserted Us into words like color, flavor, etc. even though she’d agreed to proof the book against the US Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary.)

Most of all, the editor will have been trying to make the manuscript consistent — to the standard, but especially to itself.

So, no. Your editor is not making it up.

But There Are Truths, Too, Not Just Myths

And here, just to round things out, are three truths about editors:

Truth #1: Editors love books.

Really. They do. Trust me — we don’t get into the business for the money or the fame. We become editors because we love words and we love books: books as objects, books as art, books as treasure boxes of the human mind and spirit.

We’re editing your book because that’s our job, and because we care about it.

Truth #2: Editors (mostly) love authors.

Most editors are — or wish they could be — authors. There isn’t an editor alive who hasn’t at least tried to walk the creative path you are treading. We have enormous sympathy for the challenges of expressing yourself in words. So if we occasionally ask more than you think we should, it isn’t because we don’t care; it’s because we care too much.

Truth #3: Editors can help you to create the book you dream of creating.

You are writing a book because there is something you have to say, some knowledge or wisdom to impart, some experience to which you want to lead the reader.

An editor is your partner in making that happen, helping you to say precisely what you want to say in the most effective, affecting way possible.

What are your thoughts on editing, self-editing, writing, and publishing? I’d love to hear them!

*Joseph Campbell, Myths to Live By, ebook edition, (Mill Valley, California: Joseph Campbell Foundation & Stillpoint Digital Press, 2010)

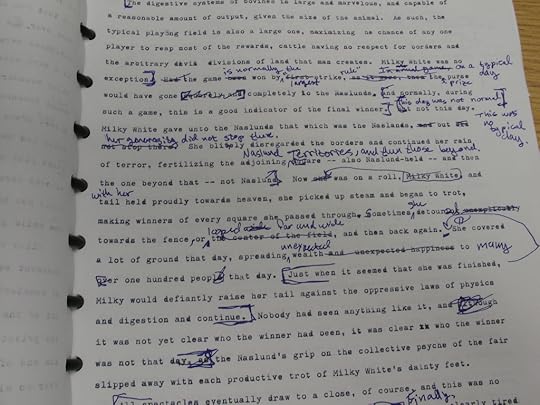

Art: “Revising, reworking, removing” by mpclemons/flickr.com. Used under a Creative Commons license.

Originally published on TheBookDesigner.com