Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 930

January 4, 2013

Unplugged on Django Unchained: A Conversation

Unplugged on Django Unchained: A Conversation by David J. Leonard & Tamura A. Lomax | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

There have been so many great discussions on Django Unchained, so many thoughtful and engaging articles, and even more critical engagements within social media. We’ve seen everything from harsh critiques to high praise, and of course everything else in between. The analyses, conversations and comments have all been challenging. Rather than write a review per se, we thought we’d have a public conversation. Regardless of how we individually interpret the film, we agree that Django needs lots of discussion. There’s still a fair amount of unsullied ground to cover, or perhaps, previously examined ground to rehash. Whatever the case may be we invite you to join us. DJL: Let me start with this: I am not a fan of Quentin Tarantino (QT), Westerns, or action films. This is not my wheelhouse so it is no wonder that I left the movie with both questions and concerns about its message and representations, and a MEH feeling about the film. I just didn’t feel it. More importantly, I find QT to be really arrogant and problematic as a filmmaker and as a PERSONA on a number of levels. His responses to critics, his self-aggrandizement, his lack of critical self-reflection, his lack of growth as a filmmaker (the fact that this film is so much like his past films is not a ringing endorsement), and the comfort in cashing in on his privileges, trouble me. My reading of the film is clouded by all of these feelings. TAL: David, let me begin by saying, “I hear you.” I hate almost all kinds of violence so I never got into QT’s films. I don’t have any preferences for action films either, and Westerns always registered as “white” in my mind. However, I loved this film! To be sure, there are numerous problems with both QT and the film. And I get your critique of QT’s persona. He absolutely comes across as self-aggrandizing, and perhaps even unreflective. One thing is for sure, QT is very much aware of his privilege. That is, he seems to understand quite well who gets to tell what story in Hollywood, and who and what’s needed for authentication. That aside, I still loved this film. I read it as a love story—one marred by both life and death of course. DJL: Speaking of violence, the violence in the film felt gratuitous at times. It was often more spectacular than a critique of white supremacist violence. There were moments where the cinematic gaze was infused with a pleasure in the violence, and that troubled me. Those scenes were early in the film – the scene involving the dogs, and slave fights, and I had to look a way because of the purpose seemed to be about eliciting pleasure from its (white) viewers. The camera’s gaze conveys pleasure and joy in in these spectacular images. It didn’t feel as if there was an interest in conveying outrage and spotlighting trauma. Rather there seemed to be an effort to bring viewers into this extreme spectacle of violence. The lack of reflection in the cinematic gaze angers me. I think about the times I have taught about the Birmingham church bombing, Emmett Till, and the history of lynchings, and how I have thought long and hard about the pain and trauma. Sometimes unsuccessful, I have looked inward in these moments, thinking how might whiteness matter when recounting these histories. I don’t feel like QT accounted for the trauma or this history. TAL: I concur. There was a lot of violence in the film, more than I could stand. But slavery was violent. Our current context is violent. But let me just say this, the continuous cannonades of blood were odious hands down. Still, I think it’s important to keep in mind that, in a captive state, death often marks the point of transition between modes of servitude and inter-subjective states of liberty. Thus, while the violence in the film was at times overwhelming, and although I really do detest violence, I was admittedly okay with some of it. I think the problem with QT, in addition to those you mentioned, is that his gaze too often waxes and wanes between voyeurism, fetishism, condescension, and black heroic genius. On one hand we get Django, a hero of sorts who kills for love and vengeance. And on the other hand, we get everyone else, a collection of seemingly disposable frozen objects who, among other things, seem cool on not only their enslavement, but the routinization of violence against black humanity around them. Along with some of the images of death, I found this to be deeply problematic. Some of the scenes were so gruesome that, in addition to looking away and/or covering my ears, I had to take a mental moment. As you've stated, QT delivers violence, perhaps even takes pleasure in it, however he doesn’t take the time to deal with or allow us to sit with the trauma. He doesn’t allow us to feel the pain of the characters; he doesn’t encourage viewers to reflect on the psychic pain of black death or the countless victimizations of white supremacy. We should problematize all of this, but perhaps QT’s offering us a mockery on life. Sometimes we take pleasure in hideous violence (isn’t this why it’s videotaped so rampant and callously?). Sometimes we find alibis for engaging the taboo. Sometimes violence is selfish. Sometimes it's unprovoked. And sometimes it's illiberal. However, sometimes violence may be just. Cathartic. Some sort of source of power. ***

Tamura A. Lomax is the Assistant Chair and an Assistant Professor of African American Studies at Virginia Commonwealth University. She teaches, writes, and researches in the following areas: American Religion, African American Religion, African American and Diaspora Studies, Gender and Sexuality Studies, and Black British and U.S. Black Cultural Studies. She is the author of several essays and is currently at work on two projects: An edited volume entitled Womanist/Black Feminist Responses to Tyler Perry’s Cultural Productions, co-authored with Rhon S. Manigault-Bryant and Carol B. Duncan, and her first single authored monograph, Womanist Thought, Black Feminism, and Black Cultural Production. She is co-founder, along with Hortense Spillers, of The Feminist Wire.

David J. Leonard is Associate Professor in the Department of Critical Culture, Gender and Race Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. He is the author of the just released After Artest: Race and the War on Hoop (SUNY Press) as well as several other works. Leonard is a regular contributor to NewBlackMan, layupline, Feminist Wire, and Urban Cusp. He is frequent contributor to Ebony, Slam, and Racialicious as well as a past contributor to Loop21, The Nation and The Starting Five. He blogs @No Tsuris.

Published on January 04, 2013 17:20

January 3, 2013

New Black Digital Sci-Fi Series: The Abandon (pilot)

The Story: The Mayan prophecy predicts the world will transform during the Winter Soltisce 2012. The Hopi believe the Blue Star Kachina will appear in the skies during the Winter Solstice 2012 and bring an alien nation to Earth and introduce the Age of Purification. In the summer of 2012 five men go on an annual hiking trip. However, things change drastically when they receive news of a global alien invasion. The Abandon follows a group of friends who must navigate and survive a global alien invasion that has changed the world forever. They have two choices: focus on their individual survival or secure the longevity of the human race.

Writer/Director Keith Josef Adkins

Published on January 03, 2013 19:44

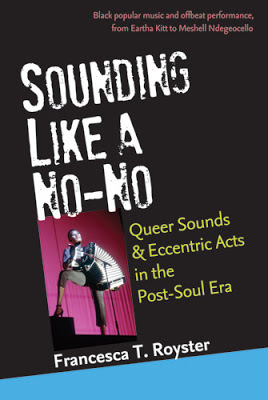

New Book—Sounding Like a No-No: Queer Sounds and Eccentric Acts in the Post-Soul Era

Sounding Like a No-No: Queer Sounds and Eccentric Acts in the Post-Soul Era Francesca T. Royster

Black popular music and offbeat performance, from Eartha Kitt to Meshell Ndegeocello

Description

Sounding Like a No-No traces a rebellious spirit in post-civil rights black music by focusing on a range of offbeat, eccentric, queer, or slippery performances by leading musicians influenced by the cultural changes brought about by the civil rights, black nationalist, feminist, and LGBTQ movements, who through reinvention created a repertoire of performances that have left a lasting mark on popular music. The book's innovative readings of performers including Michael Jackson, Grace Jones, Stevie Wonder, Eartha Kitt, and Meshell Ndegeocello demonstrate how embodied sound and performance became a means for creativity, transgression, and social critique, a way to reclaim imaginative and corporeal freedom from the social death of slavery and its legacy of racism, to engender new sexualities and desires, to escape the sometimes constrictive codes of respectability and uplift from within the black community, and to make space for new futures for their listeners. The book's perspective on music as a form of black corporeality and identity, creativity and political engagement will appeal to those in African American studies, popular music studies, queer theory, and black performance studies; general readers will welcome its engaging, accessible, and sometimes playful writing style, including elements of memoir.

"A wonderful study offering refreshing new ways of theorizing the politics of 'post-Soul' and post-Civil Rights culture. Sounding Like a No-No promises to break important new ground." —Daphne Brooks, Princeton University

Francesca Royster is Associate Professor in the Department of English at DePaul University. She is author of Becoming Cleopatra: The Shifting Image of an Icon.

Published on January 03, 2013 16:04

The NFL and America’s Drinking Problem

The NFL and America’s Drinking Problem by David J. Leonard | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

A month ago Jerry Brown Jr. lost his life. Like all too many people, each and every day, his death was the result of drunk driving. According to police reports, Brown was a passenger in the car of his Dallas Cowboys’ teammate and college roommate, Josh Brent. Travelling at what appeared to be a high speed on an interstate highway, Brent’s car struck the “outside curb, causing the vehicle to flip at least one time before coming to rest in the middle of the service road.” In just an instant one man’s life was lost and his best friend’s life would be forever changed. “Officers at the scene believed alcohol was a contributing factor in the crash,” noted John Argumaniz, an Irving police spokesman. “Based on the results and the officer's observations and conversations with Price-Brent, he was arrested for driving while intoxicated.” This is tragic on so many levels, but that is not the emergent story.

In wake of this tragic death and Brent’s arrest, a narrative emerged that sought to construct a bridge between football and drunk driving. The Memphis Business Journal parroted widely cited statistics in its piece about the “NFL’s Drinking Problem” to highlight the large problem that had tragic consequences:

In the wake of the alcohol-related death of Dallas Cowboys linebacker Jerry Brown over the weekend, the NFL may have some serious soul-searching to do.

USA TODAY reports 28 percent of the 624 player arrests since 2000 occurred because of a suspicion of driving under the influence of drugs or alcohol. The single-vehicle accident in which Brown was killed marked the third time since 1998 an NFL player killed another person due to suspected intoxicated driving, the paper reported.

Barron H. Lerner, with “Why Can't the NFL Stop Its Players From Driving Drunk?” offered a similar song, noting statistics about NFL players and arrests (yet of course failing to offer notation that this same study revealed that NFL players were less likely to engaged in this practice than their non-playing peers). He also recycled the longstanding argument that NFL players are more likely to engaged in such behavior because of the lack of moral and legal consequences:

It is reasonable to speculate that these efforts have lowered the rates of drunk driving among NFL players and, for that matter, all professional athletes. But there is still a culture of drinking and driving among NFL players. As Dan Wetzel reported on Yahoo, drunk driving is the league's biggest legal issue. A study by the San Diego Union-Tribune found that 112 of the 385 NFL player arrests between 2000 and 2008 involved drunk driving. In 2009, Cleveland Browns wide receiver Donté Stallworth, who had been drinking at a hotel bar in Florida, struck and killed a pedestrian. The problem is that there are limits to moral and legal deterrents.

Similarly, Brian Miller called for greater surveillance and punishment to address the NFL’s criminal problem:

From drugs, murder, DUI, assault and battery, the NFL needs to stand up in front and lead. They need to be tougher and frankly, Roger Goodell is a pretty tough commissioner. However, it's time that he starts landing major punches in his battle to clean up the image of the NFL. In order to do that, he will need more than simple cooperation from the (players' union). This is not an NFL issue; it's a players issue.

The narrative that imagines the NFL as a league of irresponsible drunks and criminally-minded threats to public safety dominants the landscape.

Certainly there should be a space to talk about the specific manifestations of alcoholism and drunk driving within a football sub-culture. Lets talk about it all - masculinity, self-medication, the selling of parties/lifestyles as payment for their profitable labor, and a league that makes millions off alcohol. But lets not get it twisted, alcoholism and drunk driving are a societal problem; football merely recapitulates the broader tragedies and issues within society at large. Moreover, if we are going to have this conversation, can we please have it with facts?

"The San Diego Union-Tribune reviewed hundreds of news reports and public records since January 2000 and found that the league's biggest problems with the law are in many ways just as ordinary: drunken driving, traffic stops and repeat offenders. In addition, contrary to public perception, the arrest rate among NFL players is less than that of the general population, and fueled by many of the same dynamics, analysts say.... While drunken driving arrests were the most common arrest among NFL players, the arrest rate was below that for males under 30 in the United States, which is roughly 2 percent, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. In the NFL, it's about one DUI arrest per 144 players (less than 1 percent), based on the review. Mix in lots of money, fame and expensive cars, and perhaps it's no surprise that drunken driving is the NFL's most common arrest charge. Among people ages 22-34 in the United States, DUI and drug-related offenses are the two most common charges, according to the FBI.

Irrespective of the sensationalism and aversion to facts, lets be clear: NFL players are less likely to drink and drive in comparison to those in a similar age group.

Even this data has its complications, given the realities of racial profiling. In examining traffic stops involving NFL or NBA players we need to account for race, given the leagues' demographics and given the hegemony of racial profiling. According to Peter Roby, “The whole issue of driving while black is not a figment of somebody's imagination. If (police) are on the lookout and sensitized to looking for certain people, they're probably going to find that.” If you look at studies that document each and every case involving NFL and NBA players, the number of cases where charges are dropped/never filed is telling. It should give at least some pause regarding pundits who like to cite arrest numbers, who refuse to acknowledge racial profiling.

Even with racial profiling, even when focusing on arrest rates and nothing else, the numbers still don’t point to an NFL or sports specific problem. In other words, you can talk all you want about the NFL, a culture of entitlement, and even rely on racial stereotypes, but the facts are the facts: NFL players are less likely to drive drunk than others in their age group.

And if the concern is about drunk driving, lets have that conversation. Where are the articles on college students and their drunk driving problem. Studies have found that 1 in 5 college students admit to driving drunk; over 40% admit to knowingly getting into a car with a drunk driver. Where is the media sensationalism about the culture of universities, the sense of entitlement, and the lack of moral/legal consequences? This is clearly a problem, yet the silence is telling.

Where are these same articles about CEOs and Wall Street executives and their drinking problem? If you type in drunk driving and Wall Street or any number of professions, what do you think you find, a number of cases, but no articles with Headlines, "does Wall Street or D.C." have a drunk driving problem. The tragedy over the weekend, and the issue of alcoholism or drunk driving within the NFL is a mirror into society at large. It is a window into the issues, many of which we refuse to confront, by scapegoating and criminalizing certain segments of society. Where are the sensational articles that comment on culture, criminality, and a lack of requisite punishment? Where are the stories that bundle together rather than individualize the cases involving a Florida Polo Mogul; the co-founder of Crocs or this Wall Street CEO all of whom had incidents of drunk driving (two of these cases involve fatalities). Included in such a story about the “life styles of the rich, famous, and drunk” should be the sad tale of Alix Rice, who lost her life because of a drunk driver:

A wealthy and well-connected local doctor, James G. Corasanti, was driving his BMW after spending hours as a country club—an outing at which, it was noted in the trial, Corasanti drank five rum and cokes, plus wine and champagne. He hit the teenager so hard that she was propelled 167 feet, breaking her neck and causing other injuries. Then he drove home. The doctor—whom supporters during the trial period lauded as a lifesaver for his patients, left the girl to die. He wasn't just drunk, he was speeding and texting. Further, prosecutors said, Corasanti deleted texts and removed the victim's blood and body tissue from his fancy car before turning himself in to authorities.

Despite having been cited for “driving while impaired” received ONE YEAR in prison. Lets talk about the problem of drunk driving given that 13,000-14,000 people die each year. This isn’t an NFL problem; its not a sports problems . . . it’s a society problem.

Top of Form

I know its comforting to imagine the tragic death as a symptom of the NFL (and there is a lot to criticize and loathe about the NFL); I know it is comforting to imagine the NFL as an out of control league of drunk criminals (police and criminal justice system then become solution); I know it comforting to pathologize and demonize the NFL, with its overwhelming number of African American players. I know it might even be pleasurable to imagine transgressions through black bodies, simultaneously reinforcing dominant ideas about blackness while yet again imagining whiteness as civilized, law-abiding, and harmless.

Here we can see the hegemony of Blackcriminalman trope; despite committing proportional number of crimes as any other population (or even less than frequently), the NFL and NBA player is consistently depicted as “out-of-control thugs” who are a threat to the society at hand. According to Richard Lapchick: “You can say for sure the athletes have a problem, but athletes are not the problem. They are representative of society where many of these issues are epidemic.” Confirming stereotypes and scapegoating black youth, the narrative of the criminal NFL player has larger consequences. The tragedy involving Jerry Brown and Josh Brent, as with the tragedy involving Alix Rice, should give us pause to look at the failures of society to address this public health issue ***

David J. Leonard is Associate Professor in the Department of Critical Culture, Gender and Race Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. He is the author of the just released After Artest: Race and the War on Hoop (SUNY Press) as well as several other works. Leonard is a regular contributor to NewBlackMan, layupline, Feminist Wire, and Urban Cusp. He is frequent contributor to Ebony, Slam, and Racialicious as well as a past contributor to Loop21, The Nation and The Starting Five. He blogs @No Tsuris.

Bottom of Form

Published on January 03, 2013 06:19

January 1, 2013

Democracy Now: 2012 Culture and Resistance

Democracy Now :

Today we look at the nexus of politics and art, airing highlights of our cultural coverage from the past year featuring Alice Walker, Walter Mosley, Tony Kushner, Randy Weston, Steve Earle, Randall Robinson, Toshi Reagon, Tom Morello and others. We pay tribute to the late Adrienne Rich, Gore Vidal and Whitney Houston and mark the centennial of the birth of Woody Guthrie.

Guests: Randall Robinson , founder and past president of TransAfrica and a law professor at Pennsylvania State University. He is the author of several books, including An Unbroken Agony: Haiti, from Revolution to the Kidnapping of a President. His most recent book is Makeda, his second novel.

Mark Anthony Neal , professor of black popular culture in the Department of African and African American Studies at Duke University. He is the host of the weekly webcast called Left of Black, and he blogs at newblackman.blogspot.com. He is author of several books, including What the Music Said: Black Popular Music and Black Public Culture and Songs in the Keys of Black Life: A Rhythm and Blues Nation.

Dave Isay , founder of StoryCorps and author of the new book, All There Is: Love Stories from StoryCorps.

Randy Weston , the legendary pianist, composer and pioneering jazz musician who incorporates the vast rhythmic heritage of Africa.

Walter Mosley , award-wining author of 37 books, including his series of bestselling mysteries featuring the private investigator Easy Rawlins. Mosley’s latest novel, All I Did Was Shoot My Man, follows the modern-day private eye Leonid McGill as he navigates a world filled with corporate wealth, armed assassins and family drama. His most recent work of non-fiction is Twelve Steps Toward Political Revelation.

Adrienne Rich , legendary poet, essayist and feminist who died in March at the age of 82.

Alice Walker , Pulitzer Prize-winning author, poet and activist. When Adrienne Rich was awarded the 1973 National Book Award, she refused to accept the award alone. She appeared onstage with poets Audre Lorde and Alice Walker, and the three accepted the award on behalf of all women.

Tony Kushner , renowned playwright and screenwriter. He won a Pulitzer Prize and a Tony Award for his play Angels in America, which was later made into an award-winning television mini-series. His other plays include Homebody/Kabul, Caroline, or Change and A Bright Room Called Day. His most recent play was The Intelligent Homosexual’s Guide to Capitalism and Socialism With a Key to the Scriptures.

Tom Morello , activist and musician who participated in the protests against the NATO summit.

Toshi Reagon , singing Woody Guthrie’s "This Train Is Bound for Glory," recorded live in Chicago at a concert marking Woody Guthrie’s upcoming centennial.

Steve Earle , musician, actor, author and activist. He is a three-time Grammy Award winner. He recently performed in New York at WoodyFest, a three-day concert in celebration of Woody Guthrie’s birthday. His recent novel and album share the same name: I’ll Never Get Out of This World Alive.

Eileen Myles , poet and novelist. She is the former artistic director of St. Mark’s Poetry Project. Her most recent collection is Snowflake/different streets (2012 Wave Books).

Gore Vidal , essayist, critic and author of bestselling books, Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace and Dreaming War: Blood for Oil and the Cheney-Bush Junta. He died in August at the age of 86.

Published on January 01, 2013 12:19

December 31, 2012

Django: A Baadassss Film for the Ages?

Django: A Baadassss Film for the Ages? by Stephane Dunn | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Quentin Tarantino does not promise his films will go down easy. His latest, Django Unchained, is no exception. The debate and expected criticism started before its current run in theatres. Inevitably, it’s provoked familiar discomfort about black actors playing roles like Django and Uncle Tom and concern over the legitimacy of a white director taking on black cultural oriented material and/or slavery and of course much criticism about the free use of the N-word . A film set during that era about slavery would hardly escape the appearance of that language whether it’s used once or numerous times. It might evade the word and utilize another – say “darky” but a script that engages a racist system through in part the representation of southern culture is probably going to suffer the use of such offensive language either prevalently or sparingly. Tarantino is unapologetic about his aesthetic. He knows his identity as a filmmaker, and he is a fantastic master sampler befitting a director whose work emerged within an era of worldwide hip hop cultural influence and whose work pays spectacular homage to the cult film genres that he’s been devoted to the most. For a guy who has reached the point in his career when he’s thinking about his legacy, in his words, making films for thirty to forty years down the road, having an affinity for very well-defined iconic genres, one or two of which invoke nostalgia but not critical respect, is a little risky.

Tarantino says he wanted to avoid making another one of those ‘historical’ films about slavery. Instead he stayed true to his style and a mantra Melvin Van Peebles observed when he created his controversial 1971 film, Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song. Sweetback was in part fueled by the political dynamism of Black Power, and the film’s financial success inadvertently opened the door for the explosion of one of Tarantino’s most beloved genre’s, blaxploitation. Van Peebles declared that one has to appeal to, entertain, “Brer” or the masses first. Both Sweetback (a sex show worker) and Django feature a serious underdog, an extremely disempowered every black man up against a racist culture. He evolves into a most unlikely hero who triumphs over the evil whites [the police in Sweetback and the white masters and overseers in Django] whose sole aim is to maintain the racial hierarchy.

While Django Unchainedis being marketed as Tarantino’s spin on the western, it’s more accurately a blaxploitationesque western for which Tarantino gleefully borrows signature elements from two favorites, Blaxploitation and Spaghetti Westerns. He makes full use of familiar staples in both - the revenge/payback motif and a number of iconic genre archetypes, including the beautiful damsel in need of rescue, Broomhilda (Kerry Washington), the fast gun, baadasssss hero Django (Jamie Foxx), and evil antagonists, namely Leonardo DiCapri’s ‘Monsieur’ Calvin Candie, along with, of course, lots of gun slinging and bloody scenes. One key staple of Blaxploitation films is the black hero flipping the script or taking on the whites, kicking butt, and ultimately achieving revenge and/or winning the battle. Tarantino’s Western hinges on setting his film during slavery thus heightening the stakes through the barriers the hero must face to rescue his lady love and one of his stylistic trademarks: that self-conscious playfulness that has somewhat mediated his films’ graphic violence. However, the stakes are different and more risky with Django. Tarantino must simultaneously avoid dismissing or understating the brutal implications of America’s most sinful system while offering the exhibition of extremes that his entertainment for contemporary movie audiences is rooted within. The film balances this unevenly largely because he stays within the model posed by two genres that privilege very defined plot models and an individualistic value system.

Certainly the flashbacks and images of Django and other enslaved black men and women imprisoned in some of the tortuous irons used on black people – leg shackles, muzzles, and the neck collar invoke the desired effect. They are jarring. There are others, for example, the naked, faceless Broomhilda being pulled from the hot box, screaming, after days of isolation, as her husband looks helplessly on from a distance and ‘Monsieur’ Candie ordering his hounds to literally tear apart the limbs of a poor runaway slave. One of the most disturbing is the ‘Battle Royal’, Candie’s ‘Mandingo’ fight between two enslaved men pitted in a battle to the literal death. But here, Tarantino oversteps unnecessarily indulging too much in that playfulness, his affinity for blood splattering and exploding like geysers, heads being cut off, and eyeballs being pulled from sockets, as if he can’t ever trust that the emotional impact will be spectacular enough without these.

In the case of the ‘Battle Royal’ scene, it’s already extremely discomforting. Two fancily dressed white men excitedly instruct their ‘Mandingos” to kill each other on the floor in front of them before a cozy hearth in a fancy, ‘civilized’ environment while the other black servants are forced to listen to bones breaking and the desperate grunts of the fighting men while appearing emotionless and carrying on with serving Candie and his guests. The incongruity, the barbarism in the midst of the representation of an upper crust civility, effectively speaks to the inhumanity of the system and the keepers of that system and the dehumanization of the men and women enslaved within it.

Tarantino oversteps similarly in other scenes; his fetishistic devotion to representing graphic violence and gore past b-grade flick style becomes an unwelcome interruption. The copious blood spattering and jutting bones just stop at being cheesy and so does one of the key shoot out scenes; such moments shout at us that this is a film and we shouldn’t take it too seriously even though we are invited to suspend normal reality to embrace as the real the narrative unfolding on the screen. Subtlety is not a Tarantino trademark, but he should seriously explore using it more. It would be effective even in a Tarantino film, and in particular a film like Django that dares to suggest the cruelty of American slavery while entertaining us with a compelling tough good guy and love wins story.

The overzealous exhibition of blood is not the only aspect Tarantino sometimes overplays. He’s channeling western cinema with splashes of blaxploitation and it’s a Tarantino film so of course we get an array of traditional archetypes and with them the underlying gender and racial implications. He has a lot of fun with writing rednecks and bad guys and so forth according to the typical inscriptions. However, archetypical characters in really smart contemporary films and especially in those by serious students of film and film loving directors like Tarantino, should get upset too - innovatively revised so they surprise or disturb us or they must at least be played so astutely and sincerely by the actors that imbibe then that they are utterly convincing and also hopefully provoke thoughtful interrogation.

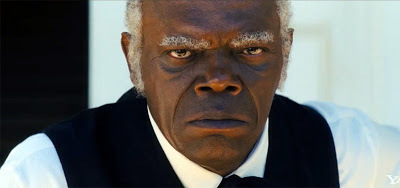

Neither is adequately achieved enough with a very important supporting character, Candie’s head slave servant Stephen, the film’s Uncle Tom, played by one of Tarantino’s favorite actors, Samuel L. Jackson. Jackson is always attention getting in whatever guise he appears on camera, and we know that playing a rascal with glee is something that suits him. His physical impersonation of the popular historical image of Uncle Tom – the almost demonic glare, white hair, prominent eyebrows, stooped shuffle, and that rascally persona, would certainly cause little children to shrink from his offer of candy. The mythic Uncle Tom has rarely been granted complex portraiture in popular culture it’s true. In Django, he’s played with an underlying comic exaggeration that’s also a familiar Tarantino character trademark. Unfortunately, Tarantino has Jackson’s ‘Uncle Tom’ swagger and ‘motherfucka’ Stephen one too many into sounding like a Blaxploitation hustler or Jackson’s Jackie Brownalter ego Ordell.

Django certainly showcases some of the filmmaking brilliance and quintessential style of Tarantino. There is beautiful cinematography as well as entertaining, strong performances by Christopher Waltz [brilliant as German bounty hunter Dr. Shultz], Foxx, DiCaprio, and even Don Johnson (Big Daddy). Yet, the film shouldn’t be constructed as one about slavery. It’s not; it is merely set against that historical backdrop and as such Tarantino invites scrutiny about how seriously he treats and represents it, and how he entertains us. For Tarantino, it is a successful film about slavery or rather western set in slavery that can stand the test of time and perhaps go down as a classic. This may prove to be true. According to him, the payback element is part of its fresh, unique cinematic treatment of slavery and one of the achievements of his story – an element that certainly added to the psychic pleasures of western and Blaxploitation flicks.

Yet, there is too much Tarantino playfulness undercutting the seriousness of a film that presumes and dares to go into historical “hell” [Tarantino’s word] and aspires to be for thirty or forty years down the road. If Django really was a white cowboy or unlikely guy, black or white, outside of the slavery setting, who mastered gun slinging then slayed a hundred dragons or bad guys to rescue his imprisoned beloved, then that might be all the expectation to fulfill. Yes, we want the hero to win, save his lady love, and live – free. Yes, it’s cool that Django gets to be a bounty hunter and thus by the authority of the law get to kill some crooked ‘crackers’ and enact payback to the slavers who’ve scarred his back and that of his woman’s. That’s the ‘entertainment’ and the psychic relief that Tarantino offers his viewers and a device that helps to keep the film from the dreaded historical with a capital “H” syndrome that previous motion pictures about slavery have fallen into according to him.

It is not enough that Django is allowed to get “dirty” in order to rescue his lady. Django has more responsibility because his is an epic situation and there are other slaves, indeed a whole system of slavery. Quite frankly, Django needs to do more than get payback on ‘Monsieur Candie and his cohorts. He also needs to care about the other slaves and whether others are left behind and function as a call to revolution. Whether he can save or free them all is beside the point. He has to care and he has to try or what’s the point of a fertile, creative mind like Tarantino that thrives on the fantastical? How could he fail to strike a blow at the system itself and dare to show Django exercise more compassion for a white boy witnessing his killer father get murdered than he does another branded, humiliated black man get torn by blood hounds?

***

Stephane Dunn, PhD, is a writer and Co-Director of the Film, Television, & Emerging Media Studies program at Morehouse College. She is the author of the 2008 book, Baad Bitches & Sassy Supermamas : Black Power Action Films (U of Illinois Press), which explores the representation of race, gender, and sexuality in the Black Power and feminist influenced explosion of black action films in the early 1970s, including, Sweetback Sweetback’s Baad Assssss Song, Cleopatra Jones, and Foxy Brown. Her writings have appeared in Ms., The Chronicle of Higher Education, TheRoot.com, AJC, CNN.com, and Best African American Essays, among others. Her most recent work includes articles about contemporary black film representation and Tyler Perry films.

Published on December 31, 2012 05:20

December 30, 2012

Berlin Conference 2.0?: U.S. Military Builds Up Its Presence In Africa

Published on December 30, 2012 18:17

Django Unchained, or, What was So Damn Funny Anyway?

Django Unchained, or, What was So Damn Funny Anyway? by Darnell Moore | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

I expected the epithet “nigger” to be overused in Django Unchained. It is a Quentin Tarantino film after all, and Tarantino is proficient in hyperbole.

I was not prepared, however, for the countless eruptions of laughter following those scenes—and there were many—in which “nigger” was used or when some other form of racist-turned-comedic line was offered. Indeed, watching Django in a crowded, downtown Brooklyn theater with a mostly white and, from what I could gather, entertained audience was as assaulting as the overdone Tarrantino-esque moments of “heroic” bloodshed. When the movie ended, my friends and I pondered how our experience might have been different if we watched the film in a theater with a predominantly black audience. Would there have been as much laughter? While a range of critical reviews has been written about the limitations and brilliance of Django, little has been said about that which the film allows, enables, and precludes. Like all cinema, Django invites spectatorship, but of a certain contextual flavor. And the spectator, as noted by documentary filmmaker Youness Abeddour, “is not simply a passive viewer, but he/she interacts in the action of the film, taking the pleasure of watching and giving a meaning to the film.” The mostly white audience members in Brooklyn were rather interactive spectators, to be sure.

The audience is offered a limited and imaginary picture of US chattel slavery as Salamishah Tillet, University of Pennsylvania professor and author of Sites of Slavery: Citizenship and Racial Democracy in the Post-Civil Rights Imagination, notes in her Ishmael Reed similarly recalled in his Wall Street Journal review that he watched Django in Berkeley “where the audience was about 95% white.” He went on to state, “They really had a good time. A row of white women sitting in front of me broke into applause as Django blew away the white mistress of the plantation who was [sic] sort of silly frivolous set up like some of the blacks in the movie.”

What do the many moments of hilarity on the part of white people viewing Django in theaters across the country communicate? And to whom?

What is, precisely, so funny about excessive use of the label, “nigger”?

Why did hundreds of white audience members in Brooklyn feel at ease snickering at the banter of Stephen (Samuel L. Jackson), the “nigger”-hating house slave in blackface who loved his owner, Calvin Candie (Leonardo DiCaprio), and protected the plantation where he was enslaved, the perversely-named Candie Land?

Why are some white people seemingly comfortable with vicarious participation in the movie’s racial violence?

These were the questions on my mind as I watched the film and wondered if I was somehow invisible in a theater surrounded by white folks who, for once, behaved as if they had license to laugh at the “nigger” on the screen and not be reprimanded by a black person in their proximity.

Indeed, Django brings to the fore the anxieties and fantasies of the white viewer and it makes space for cathartic release, namely, the passing of guilt. Some white viewers in the audience in Brooklyn, and apparently Berkeley, clapped when the always smiling Lara Lee (Laura Cayouette)–Candie’s “beautiful sister" who figured in the movie as a representation of a "good" white person among the many who were not—was blasted to her death by Django.

In the scene, Django shoots Lee and her body is forcefully thrown from a doorway, into another room, and off the screen. She is no longer visible to the audience. The brutal killing of Lee seemed to have signaled a moment in the viewing experience where justice was finally served. Lee’s killing could easily be read as signifying the exoneration of guilt maintained by some white people in the U.S. today as a result of the heartless chattel slavery industry of our past. White guilt, just like Lee's body, is literally blown away—from the screen and the conscience of the white viewer.

Django met my expectations. It was gruesome, phantasmagoric and embellished. I was not surprised by Tarantino's ahistorical and comedic moves. I was, however, troubled by three hours of white spectatorship that rendered the presence of African-Americans in the audience as spectacularly invisible. Unlike the white characters in the film who never saw a “nigger on a horse” and were too shocked to laugh when they encountered Django traveling into town, the white movie goers in Brooklyn were less modest and found reason to offer aloud their amusement at the "hilarious" racism.

Tarantino created a perverse tale of the enslaved black, and white slave owner who profited from the enslavement enterprise, which should leave all of us asking of white audiences when it’s over: What, exactly, was so damn funny?

***

Darnell L. Moore is a writer and activist who lives in Brooklyn, N.Y. Currently, he is a Visiting Scholar at the Center for the Study of Gender and Sexuality at New York University.

Published on December 30, 2012 17:45

December 29, 2012

The Wilmington 10: North Carolina Urged to Pardon Civil Rights Activists Falsely Jailed 40 Years Ago

Democracy Now :

As the new year approaches, North Carolina Gov. Bev Perdue is being urged to pardon a group of civil rights activists who were falsely convicted and imprisoned 40 years ago for the firebombing of a white-owned grocery store. Their conviction was overturned in 1980, but the state has never pardoned them. We're joined by one of "The Wilmington Ten," longtime civil rights activist Benjamin Chavis, who served eight years behind bars before later becoming head of the NAACP. We also speak to James Ferguson, a lead defense attorney for The Wilmington Ten; and to Cash Michaels, coordinator for The Wilmington Ten Pardons of Innocence Project and a reporter for the Wilmington Journal where he has been covering the activists' case.

Published on December 29, 2012 11:45

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.