Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 927

January 21, 2013

Game Changers: The One Hood Media Academy

1HoodMedia

Jasiri X and Paradise Gray of One Hood Media are Game Changers who are teaching young black men how to play the media game and control their own images. In this day of the Internet they don't need anyone's permission to blog or shoot their own videos, they control the vertical and the horizontal, and thus they realize the power that they have to change the way they are perceived in popular culture. It is a transformative moment when these students finally get in the game, they become Game Changers.

Game Changers was written and produced by Chris Moore for WQED TV.

Published on January 21, 2013 14:07

January 17, 2013

Behind The NRA's Money: Gun Lobby Deepens Financial Ties to $12 Billion Firearms Industry

DemocracyNow

Throughout its history, the National Rifle Association has portrayed itself as an advocate for individual gun owner's Second Amendment rights. But a new investigation finds the group has come to rely on the support of the $12-billion a year gun industry -- made up of firearms and ammunition manufacturers and sellers. Since 2005, the NRA has collected as much as $38.9 million from dozens of gun industry giants, including Beretta USA, Glock, and Sturm, Ruger & Co., according to a 2011 study by the Violence Policy Center. We speak with investigative reporter Peter Stone, whose latest article for The Huffington Post is "NRA Gun Control Crusade Reflects Firearms Industry Financial Ties."

Published on January 17, 2013 04:04

The Stupidity Of New York's Long, Expensive (And Ongoing) War On Graffiti

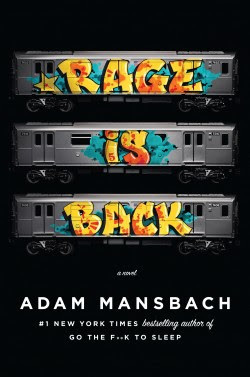

The Stupidity Of New York's Long, Expensive (And Ongoing) War On Graffiti by Adam Mansbach | special to NewBlackMan

Thirty years ago—at the height of New York City's "War on Graffiti," and in an act of faith utterly incommensurate with the city's public demonization of graffiti writers—a group of teenagers named SHY 147, DAZE, MIN and DURO met with MTA official Richard Ravitch, and proposed a deal. Give the writers of New York City one train line to adorn with their vibrant aerosol murals, and they would leave the rest alone. Let them paint for six months, then let the public vote on the merits of their contribution.

Ravitch suggested that if the writers wanted to contribute, he would give them all brooms, and hostilities resumed. The subway's exteriors have been art-free since 1989, but the war has never really ended. New York City remains rigidly opposed to the very aesthetic of graffiti—even if the art in question is perfectly legal.

Today, advertisers have learned to faithfully, if flavorlessly, appropriate graffiti's ethos of logo repetition, as anyone who has ridden the train lately can confirm. In the city that incubated the most important popular art movement of the 20th century, the message is clear: public space can be yours, if you pay for it.

Unless what you put there reminds them of graffiti, that is. I learned this last week, when I tried to buy space to advertise my new novel. The silver walls where "burners" used to blaze are now for rent; anyone willing to pay fifty thousand dollars to a company called CBS Outdoor can buy advertising "stripes" for a month. For considerably more, one can "wrap" an entire train in product messaging.

"The issue," CBS Outdoor wrote in an email, explaining why my proposal had been rejected, "is the style of writing. The MTA wants nothing that looks like graffiti."

Admittedly, my book title is rendered in colorful, flowing letters, by the Brooklyn artist Blake Lethem. Admittedly, this would not have been the first time Mr. Lethem's work had graced a train. But what exactly is the rubric by which the MTA judges a letter's graffiti-ness? At what stylistic tipping point does a word becomes impermissible to the same entity that has approved liquor adverts depicting naked women in dog collars, and bus placards featuring rhetoric widely condemned as hate speech against Palestinians? And if the NYPD defines graffiti as "etching, painting, covering or otherwise placing a mark upon public or private property, with the intent to damage," isn't a graffiti-style letter kind of like a robbery-style purchase?

All this might seem trivial, except that the War on Graffiti's tactics presaged a generation's experience of law enforcement and personal freedom. Mayor John Lindsay first declared war in 1972, and over the next 17 years, the city would spend three hundred million dollars attempting to run graffiti-free trains—this, during a period when the subway barely functioned and the city teetered on the brink of insolvency. Clearly, there was more at stake than aesthetics.

Those stakes become clearer when one examines law enforcement's public profiling of graffiti writers. They were described as "black, brown, or other, in that order," and vilified as sociopaths, drug addicts, and monsters. This was a fight over public space, and we would do well to remember that at the time the fight began, teenagers were also being arrested for breakdancing in subway stations, and throwing un-permited parties in the asphalt schoolyards of the Bronx. Taken collectively, these three activities also represent the birth of hip-hop, the single most influential sub-culture created in this or any country in the last half-century.

As historian Jeff Chang writes, the early 70s saw the politics of abandonment give way to the politics of containment in communities of color. The War on Graffiti is a prime example, and it midwifed today's era of epic incarceration, quality of life offenses, zero tolerance policies, prejudicial gang databases, and three-strike laws. The War on Graffiti turned misdemeanors into felonies, community service into jail time. It put German Shepherds to work patrolling the train yards; Mayor Koch once suggested an upgrade to wolves. Today, the city prosecutes hundreds of graffiti cases each year, and maintains a dedicated Citywide Vandals Task Force. Nationally, writers have been sentenced to prison terms as long as eight years, and ordered to pay six-figure restitutions. In other words, the war rages on.

One cannot help but wonder what might have happened if New York City had agreed to the naïve, visionary truce those four teenagers offered, 30 years ago now. With a handful of scholarships and a press release, might the "graffiti plague" have been alchemized into a landmark public art program, to be adapted by other cities with the same zeal that zero tolerance has been? Could thousands of lives have been altered, hundreds of millions of dollars better spent?

We'll never know, because the city didn't listen to its young people then. It didn't recognize graffiti as an outpouring of creativity and frustration, a simultaneous urge to beautify and destroy, to hide and be seen, that's every bit as complicated as being shunted to the margins of the American dream. Kids are still writing graffiti today, beautifully and badly, in every city in the world; New Yorkers taught them how to do it, but they've always understood why. It's not too late to listen to them now.

***

Adam Mansbach is the author of the #1 New York Times bestseller Go the F**k to Sleep and the novel Rage Is Back, available now from Viking.

Published on January 17, 2013 03:51

January 16, 2013

HuffPost Live: Is a Hip-Hop Studies Minor Legitimate?

Huffpost Live: The University of Arizona has introduced a minor in hip-hop studies. Does this represent a watering down of the traditional curriculum or a brave new intellectual turn?

Hosted by: Marc Lamont Hill GUESTS: Charles Johnson (Los Angeles, CA) Blogger Davey D (Oakland, CA) Hard Knock Radio Host; Teaches Black Music & Hip-Hop at San Francisco State University @mrdaveyd Alexander E. Nava (Tucson, AZ) Professor of Religion; Taught First Class on Hip-Hop at University of Arizona Imani Perry (Princeton, NJ) Professor at the Princeton Center for African American Studies @imaniperry John Turner (Indianapolis, IN) Professor at Ivy Tech Community College @theprofessor_JT

Published on January 16, 2013 16:50

January 15, 2013

Denzel Washington, Flight and ‘New Negro Exceptionalism’

Denzel Washington, Flight and ‘New Negro Exceptionalism’ by Usame Tunagur | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences recently announced its 2013 Oscar nominations. Nominated in the Best Actor category for his strong performance in Flight (2012), Denzel Washington received his 6th Oscar nomination, making him the most nominated black actor. So far, he has won the hardware twice; one for Best Supporting Actor in Glory(1989) and another one for Best Actor in Training Day (2001).

In Robert Zemeckis’ film Flight, Denzel Washington plays the role of an alcoholic and an accomplished pilot; a character packaged with subtle clues hinting at a generational burden of representation and the possibility of a complex humanization. Whip Whitaker is an extremely skillful veteran commercial airlines pilot who pulls off a spectacular emergency landing, saving all but six of 102 passengers after an unheard of upside-down maneuver —a maneuver the nation’s top 10 pilots failed to achieve in flight simulations. Under normal circumstances, this would make him an instant hero. However, Whip is totally drunk and has serious amounts of cocaine in his veins during this flight. The rest of the film proceeds through Whip’s challenge with his addiction along with an NTSBinvestigation and a hearing that threatens him with prison time. Reminiscent of the young black pilot who crashes his plane during a Tuskegee training flight in Ralph Ellison’s short story Flying Home, Whip (also) has to come to terms with who he is not in the skies —a space historically cherished by many African Americans as an abode away from socio-political realities of oppression, violence and inequality— but rather on the ground, and finally rise up again in the vein of the mythological Phoenix.

Flight’s arc operates on a failure to accept and deal with addiction. Nevertheless, upon a closer reading, the core issue is control. Cynthia Fuchs writes in popmatters.com, “[Flight] makes it too easy to read addiction as a moral failing, a lapse of judgment that the rest of us might judge easily. But the issue is not morality. It’s not having control.” Possibly, hidden underneath Whip’s drug and alcohol addiction is an internalized reflex to control his black image. Throughout the film, Whip operates with an illusion of control. In an effort to help him, Whip’s recovering addict white girlfriend Nicole (Kelly Reilly) invites him to an AA meeting. Whip unwillingly obliges. In the middle of the AA meeting, Whip feels extremely uncomfortable with what he perceives to be preachy, and goes home alone. Later, when questioned by her, they argue and she leaves. Whip yells behind her “I choose to drink!” He actually yells at the audience too, as he almost directly faces the lens. This urge to underscore his control, by denying a major weakness, works against Whip accepting his lack of control. His motivation might be very well linked to a generational trait in which he has found himself; As his forefathers policed and categorized black images with brush strokes via “good vs. bad” or “positive vs. negative” binaries, Whip, a stone cold alcoholic, works really hard to project a positive image against fanning the fire of popularized and mediated black pathology.

Whip is the son of a Tuskegee airman who, after the Second World War, continued flying planes for his crop dusting business in Georgia. As Whip’s dad was a Tuskegee airman, it is highly probable his father and grandfather both would have been imbued by the ideology of the New Negro spearheaded by Booker T. Washington The negro of today is in every phase of life far advanced over the negro of thirty years ago. In the following pages the progressive life of the Afro-American people has been written in the light of achievements that will be surprising to people who are ignorant of the enlarging life of these remarkable people.

Military success by Black Soldiers on the battlefields—in the civil war, WW1 and others—was a key component of the New Negro image. As Henry Louis Gates, Jr. explains, “of this anthology’s eighteen chapters, no less than seven are histories of black involvement in American wars…” Living up to the New Negro image and exemplifying a masculine military might, Whip’s father would have ultimately added to the project of creating a purely positive representation.

Enter Whip Whitaker. This post-New Negro generation Blackamerican would have felt the burden of positive representation and projection embodied by his father. This burden might have added to an inability to accept his heavy alcohol and drug addiction. He couldn’t accept, let alone announce, his drinking problem, as this would have constituted race treason; Coming out as an alcoholic Black man would be almost backstabbing the image that New Negro Exceptionalism highlights. In 1904, Voice of the New Negro magazine published an article called The New Negro Man about the essential qualities —both in terms of character and physical features— of the ideal Black Men, along with 7 portraits.

This list did not have a category for a successful pilot who also happens to be an alcoholic, drug addict and an absent father/husband. These portraits were purely positive prototypes, which did not completely fit in with the complex and diverse realities of the black experience on the ground. As a member of a generation that happened to find the New Negro baton on their laps to continue the efforts to self-project a pristine image, Whip might have felt obliged to project only perfection. So, the more he diverted from the positive image packaging of this ideology in his day-to-day reality, the more introverted and self-denying he might have become.

After he leaves the hospital where he is treated for minor injuries caused by the emergency landing, in order to stay away from news reporters’ abuse, Whip hides himself in his father’s old farmhouse that was home to his crop dusting business. It is interesting that Whip goes through most of the film in this place that he’s been trying to sell for years. This desire to sell the farmhouse stems from a desire to move on from his past. But he actually has not sold it, as he has not moved on yet. It is not in the farmhouse that he faces his demons as the farmhouse is New Negro / Positive Image Projection Territory. Here, he drinks chronically. But he hides it like dirty laundry, instead of facing, humanizing, and challenging his experience. One night, while he is again heavily drunk in the farmhouse, he watches a home video he shot probably ten years ago where his father is playing football with his son.

This is the only time we see Whip, his father and son, three generations all together, within the same scene. Whip’s positioning here is powerful. He is watching two people on the screen from whom he is disconnected; one by death, the other by lack of responsibility. Whip knows deep down that he couldn’t live up to his father’s expectation of an archetypal black Hercules. He also sadly watches the result of that failure reflected in his lack of relationship with his own son. Whip’s addictions might be personal but their repercussions have a direct impact in his relationships, especially with his wife and son. Here, that lack of control deepens as the only way of seeing his son is through an old home video. The disconnect between the complex human being that Whip really is and the image he tries to project –flawless, successful, black man—creates a fragmented individual who is unwilling to face his domestic challenges. Furthermore, this moment of three generations in one scene is important since Whip’s son represents the post-Hiphop generation; the generation that stands on the other end of the spectrum.

Whip stands in between these two general historical traits; namely the New Negro and Hiphop generations. As the New Negro era was underscored by efforts of positive representation, the Hiphop era became a social canvas on which all shapes of black pathology were drawn all the while a prefigured “keepin’ it real” urban authenticity serving as its engine. On the one hand, Whip’s upbringing was fueled by New Negro Exceptionalism, on the other hand, his pilot career would have coincided with the Hiphop era. According to Akil Houston, “the Hiphop Generation(ers) are people whose birth years include the period between 1965-1984…[They] are the first to have grown up in a post-segregation United States. These are specific years although much of mass media would create the perception that anything connected to youth culture is the Hiphop Generation.” This timeframe was emblematized by crime, drug epidemic and urban marginalization –outcomes of Reaganomics–, ultimately popularizing “black pathology” nationwide.

As James Braxton Peterson powerfully argued on a recent TV interview, “there is a tremendous American appetite for Black Pathology.” Intensified media coverage of black-centered homicide and drug/alcohol addiction, typical of the Hiphop era, would have pressured Whip even more to hide his condition. Some Hiphop generationers glorified this pathology –either to criticize and call attention to its causes or to shock-and-awe—without any apology, at the same time fitting in to a limited and limiting “Black authenticity.” However, Hiphop generation’s discourse of confidence —different than the Black pride the New Negro espoused—was not available to Whip while growing up a Tuskegee man’s son, since he was born too early to become a part of the Hiphop Generation.

In this vein, it is interesting that Whip’s breaking point does not take place in the farmhouse. It rather happens in public. It was always for public perception that he felt obliged to self-project positively. Thus, the cathartic metamorphosis had to happen before them in the spirit of Baptism by fire. It is only in the public eye —whose gaze has historically created, situated, frozen, and interrogated black representations, also prompting black projections to challenge or undo them—that Whip breaks down, accepts his addiction and lack of control. For the first time, he metaphorically flies away from the confines of New Negro Exceptionalist self-representation. During the climax scene, he finally agrees to being an alcoholic and a drug addict. Outside of the farmhouse —the New Negro Territory— and before the judgmental gazes of the public, he taps into his own complex human existence in between his father’s and son’s generations. In other words, he carves a personal space for himself in between New Negro Exceptionalism and Hiphop “Keepin’ it Real” Limited Authenticity.

This referencing of facing one’s humanity and breaking off from self-imposed enslavement of image projection is further hinted at the very end of the movie. In the very last scene, Whip’s son visits him in prison and asks to interview him for his college application essay entitled “The Most Fascinating Person I’ve Never Met.” It is an emotional and powerful scene, watching a father face his long-avoided son. His son asks him “who are you?” Whip responds with “Who am I? That’s an interesting question.” As Whip begins to respond to his son’s question, credits roll; We as the audience are expected to continue the dialogue and fill in the blanks. Whip’s response clearly suggests an honest attempt at self-discovery. Leaving the rest of the dialogue undone points to a multiplicity of perception, in that, each one of us will have a different perception of who Whip really is. In addition, his son’s question about who he is triggers the reading of Whip’s humanity beyond singular definitions, hence deepening and complicating his identity, rendering it a combination of many attributes and experiences. Consequently, he is neither a black Hercules nor a black dissolute, rather a dynamic amalgamation. This epilogue then compliments the climax scene towards portraying Whip as occupying a more complex human space beyond New Negro’s representational burden.

Talking about prison, one sore aspect of Flightis how it underscores the prison system as an ideal rehabilitative abode for black pathology. Reminiscent of Denzel in Malcolm X, Whip announces to a number of prison mates that he is free for the first time in his life —being sober for about a year and taking control in his life. Even though this epilogue might work for Flight's plotline, it nevertheless whitewashes and distracts from the realities of the American prison system given its overall poor record of disproportionate incarceration, high recidivism and low rehabilitation rates. The prison system as a solution is suspect in the most modest assessment. In reality, in and of itself it might be viewed as a cause of the problem, instead of a solution, especially for the black community. A quick look into Michelle Alexander’s book New Jim Crow would be more than sufficient to get a glimpse into the realities of the prison system with its intricate connection to Blackamerican males. Hence, Flight’s almost rosy portrayal of the prison, which projects it as a desirable and a curing location for addiction and criminality, is problematic to say the least.

Considering the above reading into Whip Whitaker’s psychological motives vis-à-vis generational traits of black representation, especially given the fact that this is a high budget, Hollywood flick, Flightis commendable in referencing human complexity –although limited– in a black male body.

***

Usame Tunagur works as a video producer at Everest Production whose mission is to create programming promoting diversity and multicultural celebration. His short films have received numerous awards and screened globally at various film festivals. He is also a recipient of the 2010 National Association for Multi-Ethnicity in Communications Award for the TV show, World in America.

There are a number of important visionaries and leaders within the New Negro Movement, who happened to disagree on major points. The debate between W.E.B. DuBois and B.T. Washington is possibly the most well known among these. However, they all agreed on representing the race in the best light. Being a Southerner and a Tuskegee Airman, Whip’s father would have most probably been more drawn to a Washingtonian New Negro than a DuBoisian or later a Lockean one.

Published on January 15, 2013 15:24

Black Men vs Mass Incarceration

1HoodMedia

Hip-Hop Artist/Activist Jasiri X interviews Charles X. Cook, owner of One on One Personal Fitness, for GAME CHANGERS PROJECT. Charles tells the story of how he went from a highly recruited High School basketball player, to drug dealer, to federal prisoner for 17 years, to now the owner and operator of his own gym.

The GAME CHANGERS PROJECT is a national media fellowship program for emerging black filmmakers in partnership with community-based organizations dedicated to improving outcomes for males of color.

Published on January 15, 2013 04:30

January 14, 2013

Democracy Now: Lawrence Lessig on Aaron Swartz

DemocracyNow

Today we remember the pioneering computer programmer and cyberactivist Aaron Swartz, who took his own life Friday at the age of 26. As a teenager, Swartz helped develop RSS, revolutionizing how people use the internet, going on to co-own Reddit, now one of the world's most popular sites. He was also a key architect of Creative Commons and an organizer of the grassroots movement to defeat the controversial House internet censorship bill, The Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA), and the Senate bill, The PROTECT IP Act (PIPA).

Swartz hanged himself just weeks before the start of a controversial trial. He was facing up to 35 years in prison sneaking into the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and downloading millions of articles provided by the subscription-based academic research service JSTOR. We hear Swartz in his own words and speak to Harvard Law School Professor Lawrence Lessig, a longtime mentor and friend. "There are a thousand things we could have done, and we have to do because Aaron Swartz is now an icon, an ideal," Lessig says. "He's what we will be fighting for, all of us, for the rest of our lives." Lessig also echoes the claims of Swartz's parents that decisions made by prosecutors and MIT contributed to his death, saying: "This was somebody who was pushed to the edge by what I think of as kind of a bullying by our government."

Published on January 14, 2013 10:07

January 13, 2013

Left of Black S3:E15 | Filmmaker Byron Hurt Discusses His New Film 'Soul Food Junkies' and 'Django Unchained'

<!-- /* Font Definitions */ @font-face {font-family:Times; panose-1:2 0 5 0 0 0 0 0 0 0; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:3 0 0 0 1 0;} @font-face {font-family:Cambria; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:3 0 0 0 1 0;} /* Style Definitions */ p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-parent:""; margin:0in; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-ascii-font-family:Cambria; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Cambria; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Cambria; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;} a:link, span.MsoHyperlink {mso-style-noshow:yes; color:blue; text-decoration:underline; text-underline:single;} a:visited, span.MsoHyperlinkFollowed {mso-style-noshow:yes; color:purple; text-decoration:underline; text-underline:single;} @page Section1 {size:8.5in 11.0in; margin:1.0in 1.25in 1.0in 1.25in; mso-header-margin:.5in; mso-footer-margin:.5in; mso-paper-source:0;} div.Section1 {page:Section1;} </style> <iframe allowfullscreen="allowfullscreen" frameborder="0" height="245" src="http://www.youtube.com/embed/jU5l3cp0hI0" width="435"></iframe><br /><br /><span style="font-size: small;"><b>Left of Black S3:E15 | Filmmaker <i>Byron Hurt</i> Discusses His New Film <i>Soul Food Junkies</i> and <i>Django Unchained</i></b></span><br /> <br /><div class="MsoNormal" style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-family: Times; font-size: small;">Byron Hurt’s late father was like the many Americans whose unhealthy diets led to a shortened lifespan. Alarmed by what he saw as a problem among African Americans, <b>Byron Hurt</b>, whose last film was the award-winning <i>Hip-Hop: Beyond Beats and Rhymes</i> decided to a more intimate look eating habits within Black communities. With <i><a href="http://www.itvs.org/films/soul-food-j... Food Junkies</a></i>, Hurt travels from his New Jersey home to the deep South to find out more about Soul Food and its lasting effects on Black communities. Among those featured in <i>Soul Food Junkies</i>, which debuted on the PBS series <i>Independent Lens</i> on January 14<sup>th</sup>, are eco-chef and food activist <b>Bryant Terry</b>, <b>Sonia Sanchez</b>, <b>Dick Gregory</b>, <b>Michaela Angela Davis</b>, and <b>Marc Lamont Hill</b>.</span></div><br /><div class="MsoNormal" style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-family: Times; font-size: small;">On the Spring Premiere of <b>Left of Black</b> Byron Hurt talks to host and Duke University Professor <b>Mark Anthony Neal</b> about his journey to <b>Soul Food Junkies</b>, the connection between healthy lifestyles and Black masculinity, the challenges faced by Black documentary filmmakers and the controversy surrounding Quentin Tarantino’s new film <i>Django Unchained</i>.</span></div><br /><div class="MsoNormal" style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: small;"><span><span style="font-family: Times;">***</span></span></span></div><span style="font-size: small;"></span><div class="MsoNormal" style="margin: 0.1pt 0in; text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: small;"><span><span style="font-family: Times;"> </span></span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="margin: 0.1pt 0in; text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: small;"><span><span style="font-family: Times;"><a href="http://leftofblack.tumblr.com/"&... of Black</a>is a weekly Webcast hosted by Mark Anthony Neal and produced in collaboration with the <a href="http://jhfc.duke.edu/">John Hope Franklin Center</a> at Duke University.</span></span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="margin: 0.1pt 0in; text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: small;"><span><span style="font-family: Times;"> </span></span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="margin: 0.1pt 0in; text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: small;"><span><span style="font-family: Times;">***</span></span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="margin: 0.1pt 0in; text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: small;"><span><span style="font-family: Times;"> </span></span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="margin: 0.1pt 0in; text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: small;"><span><span style="font-family: Times;">Episodes of <strong><span style="font-family: Times;">Left of Black</span></strong> are also available for free download in @ <a href="http://itunes.apple.com/us/itunes-u/l... style="color: blue; font-family: Times;">iTunes U</span></strong></a></span></span></span></div>

Published on January 13, 2013 17:45

Filmmaker Byron Hurt Talks About His New Film Soul Food Junkies on the Spring Premiere of ‘Left of Black’

Filmmaker Byron Hurt Talks About His New Film Soul Food Junkies on the Spring Premiere of ‘Left of Black’

Byron Hurt’s late father was like the many Americans whose unhealthy diets led to a shortened lifespan. Alarmed by what he saw as a problem among African Americans, Byron Hurt, whose last film was the award-winning Hip-Hop: Beyond Beats and Rhymes decided to a more intimate look eating habits within Black communities. With Soul Food Junkies , Hurt travels from his New Jersey home to the deep South to find out more about Soul Food and its lasting effects on Black communities. Among those featured in Soul Food Junkies, which debuts on the PBS series Independent Lens on January 14th, are eco-chef and food activist Bryant Terry, Sonia Sanchez, Dick Gregory, Michaela Angela Davis, and Marc Lamont Hill.

On the January 14th episode of Left of Black Byron Hurt talks to host and Duke University Professor Mark Anthony Neal about his journey to Soul Food Junkies, the connection between healthy lifestyles and Black masculinity, the challenges faced by Black documentary filmmakers and the controversy surrounding Quentin Tarantino’s new film Django Unchained.

***

Left of Black airs at 1:30 p.m. (EST) on Mondays on the FranklinCenterAtDukeChannel on Youtube: http://www.youtube.com/user/FranklinCenterAtDuke

Viewers are invited to participate in a Twitter conversation with Neal and featured guests while the show airs using hash tags #LeftofBlack or #dukelive.

Left of Black is recorded and produced at the John Hope Franklin Center of International and Interdisciplinary Studies at Duke University.

***

Follow Left of Black on Twitter: @LeftofBlack Follow Mark Anthony Neal on Twitter: @NewBlackMan Follow Byron Hurt on Twitter: @ByronHurt

Published on January 13, 2013 17:45

Into the ‘Wild’: The Arresting Poetry of Beast of the Southern Wild

Into the ‘Wild’: The Arresting Poetry of Beast of the Southern Wild by Stephane Dunn | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Practice saying this name and remember it: Quvenzhané Wallis. At nine years old, she is Oscar’s youngest nominee ever for best actress. Beasts of the Southern Wild, filmed in Mississippi and set in southern Louisiana, is Benh Zeitlin’s debut film, is this year’s little film that could. It’s nominated best director, screenplay, and best picture as well. I was intrigued by the title and trailer alone as it began to pick up steam in the afterglow of Sundance. I had some ambivalence too after exploring the synopsis and getting a glimpse. I went to see it alone one weekend afternoon in the fall. Two things became very clear in the first few minutes. Little Ms. Wallis, then only six years old, was absolutely mesmerizing; I literally could not take my eyes off her. And secondly, [I predicted] audiences would find it challenging to read, beautiful and haunting or extremely disturbing or an uneasy mix of all three as I did.

Zeitlin’s story about a fiercely proud, flawed father raising his daughter Hush Puppy [Mom has either abandoned them or died] in the squalor of the Bayou left devastated by the hurricane dares to play with symbolism and montage – a risky mix in our blockbuster, narrative happy, Hollywood film culture. In a larger sense, Beasts portrays a fiercely proud community’s challenge, even mocking, of the power of the hurricane and the levees. It is a community that clings admirably and blindly in some ways to a cultural identity and way of life inseparable from its geographical roots in the ‘Bathtub’ in southern Lousiana. The film does not unfold as an entreaty to help the still struggling Bayou – though certainly it highlights and reminds us of the storm’s inescapable devastation and trauma on the people. Instead, it tries to challenge what will presumably be our reading of the people and their home – dysfunctional, inappropriate, ignorant, needy etc. It doesn’t achieve this completely successful as its dogged representation of the squalor and traumatized landscape almost overwhelms the film. It opens with shots highlighting the environment – the trash, the overladen shacks the daughter and father call home then settles on baby faced Wallis, wild haired and bare foot in a ratty shirt and underwear.

If these visuals throughout the film aren’t enough, the depiction of the father Wink – played utterly unrelenting and arrestingly by real-life bakery owner and newcomer to film, Dwight Henry, and the father and daughter’s relationship is enough to raise inevitable questions and invoke disturbance alone. The father is rough, harsh really; he pushes beyond what could be comfortably considered as tough love for the sake of toughening up his little girl for her survival. The little girl has to be at once submissive to him and dependent on him for food and shelter and protection yet extremely independent and self-efficient, and almost maternal in her stewardship of an ailing, emotionally inconsistent father. This, along with the provocative title ‘wild beasts of the southern wild’ and the stark physical portrayals was bound to illicit questions and charges. Does it exploit Hushpuppy, misrepresent the culture, the people, and the misfortune the hurricane brought on? Does it demonize poor people, especially African Americans, black men and, black fathers in particular and show black folk culture in a negative manner? Is the film merely an exhibition of white liberal glamorization of poverty – an easy charge to a film that privileges the stark neglect and lack characterizing the material lives of Wink, Hushpuppy and the other Bathtub inhabitants?”

African American audiences are understandably sensitive about film imagery of black fathers and black parenting in general since they are and have been demonized and associated with pathology and family dysfunction for so long. Buzz about a film depicting a “bad” or abusive black father can immediately put many African American viewers on the defensive and keep them away from a film as Precious, despite industry applause, and films before have proven. If the film has a white director then the scrutiny and concern intensifies.

Back in September, bell hooks, a cultural critic who has blessedly never shied away from telling it like she sees a film, critically acclaimed or not, took on the film in “ No Love in the Wild ,” observing that critics by and large were carried away applauding the wholesale endorsement of the film’s “compelling cinematography, the magical realism, and the poetics of space.” She argues that the film’s vibrancy is fueled by its “crude pornography of violence.” The film, she goes on, reinforces “patriarchal masculinity” as the Bathtub is a natural universe where the people are one with nature and the men, represented by the father, are unquestioned. Her charges are bolstered by the implications of the language – as Wink’s model of toughness is clearly gendered masculine and it is this he certainly tries to instill in his daughter. His highest praise of her is, hooks reminds us, “You’re the man.” Beasts of the Southern Wild is indeed arresting poetry – visually – at points too much to the neglect of the story’s development. It reminds me of a point that hooks made about films years ago: A film can have strikingly conservative and radical elements. Beastshas troubling politics of representation as hooks argued insightfully and passionately. Yet, I would argue too, that despite other criticism to the contrary, it doesn’t merely indulge in mythologizing the moral dignity of poverty but rather wants to suggest the very real resilience of the human and cultural spirit of people in the midst of suffering and who are unapologetically proud of being folks whose identity is inextricable from their Louisiana, hurricane ridden, homeland and who would rather die rather than abandon that tie. The casting of non-actors from Louisiana helps to convey that genuine ethos.

Beasts of the Southern Wild is problematic and cinematically striking. It is an interesting piece of filmmaking with stunning performances, especially from Wallis and Henry. It does not go down easy; it presents an opportunity to extend the critical dialogue about the implications of cultural and class representations which Hurricane Katrina stirred up and beyond that to engage how it participates in the legacy of black male and female representation. Up until now, in contrast to the highly engaged Django, Beasts of the Southern Wild, hasn’t received nearly enough black critical consideration, whether enthusiastic or not, and has flown a little under the radar with popular movie loving African American viewers and not out of just ambivalence about the possible politics but the style as well as a film that registered perhaps as being artsy. Like The Help, it is being legitimized by Oscar, maybe the nominations will help fuel more black critical discussion about the film. Whether we see Beasts of the Southern Wild and engage it or not, a six year old black girl has made it a history making moment.

***

Stephane Dunn, PhD, is a writer and Co-Director of the Film, Television, & Emerging Media Studies program at Morehouse College. She is the author of the 2008 book, Baad Bitches & Sassy Supermamas : Black Power Action Films (U of Illinois Press), which explores the representation of race, gender, and sexuality in the Black Power and feminist influenced explosion of black action films in the early 1970s, including, Sweetback Sweetback’s Baad Assssss Song, Cleopatra Jones, and Foxy Brown. Her writings have appeared in Ms., The Chronicle of Higher Education, TheRoot.com, AJC, CNN.com, and Best African American Essays, among others. Her most recent work includes articles about contemporary black film representation and Tyler Perry films.

Published on January 13, 2013 09:38

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.