Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 856

November 12, 2013

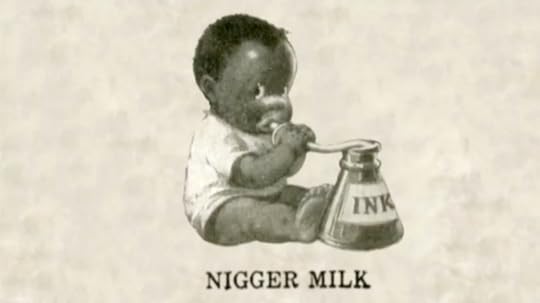

Many Rivers to Cross: Racist Images and Messages in Jim Crow Era

PBS | The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross with Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

PBS | The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross with Henry Louis Gates, Jr.Racist images in the Jim Crow era were used as propaganda to send messages that demeaned African Americans and legitimized violence against them. A visit to the Jim Crow Museum at Ferris State University in Michigan—home to the largest collection of racist memorabilia in the country—reveals racist memorabilia and messages in all forms, from kitchen utensils to postcards featuring images of public whippings. Among the museum’s collection is a row of caricatures—the Pickaninny, the Tom, the coon, the tragic mulatto, the Jezebel, the savage.

“All groups, all racial and ethnic groups in this country have been caricatured. None of them has been caricatured as often and in so many ways as have Africans and their American descendants,” says David Pilgrim, founder of the Jim Crow Museum.

Published on November 12, 2013 16:15

Left of Black S4E9: ManyVoices: LGBTQ Justice in the Black Church and a “Killadelphia Memoir’

Left of Black S4E9: ManyVoices: LGBTQ Justice in the Black Church and a “Killadelphia Memoir’

Left of Black S4E9: ManyVoices: LGBTQ Justice in the Black Church and a “Killadelphia Memoir’Left of Black host and Duke University Professor Mark Anthony Neal is joined in-studio at the John Hope Franklin Center by Rev. Cedric Harmon, Co-Director of Many Voices: A Black Church Movement for Gay and Transgender Justice and filmmaker and photographer Katina Parker, creative director behind the Many Voices Video Campaign.

Later Neal is joined in-studio by writer and poet MK Asante, who talks about his new memoir Buck and growing-up and finding his voice in “Killadelphia.”

Left of Black is a weekly Webcast hosted by Mark Anthony Neal and produced in collaboration with the John Hope Franklin Center at Duke University.

***

Episodes of Left of Black are also available for free download in @ iTunes U

***

Follow Left of Black on Twitter: @LeftofBlackFollow Mark Anthony Neal on Twitter: @NewBlackManFollow ManyVoices on Twitter: @ManyVoicesOrgFollow Rev. Cedric Harmon on Twitter: @RevCedricMVFollow Katina Parker on Twitter: @KatinaParker

Follow MK Asante on Twitter: @MKAsante

Published on November 12, 2013 03:45

Hutchins Center Colloquium feat Christopher Emdin: Colloquial Appropriations of Canonical Science through Hip-hop Education (11/13)

Hutchins Center Colloquium feat Christopher Emdin:

Colloquial appropriations of canonical science through hip-hop education

Hutchins Center Colloquium feat Christopher Emdin:

Colloquial appropriations of canonical science through hip-hop education

Location:

Harvard UniversityThompson Room, Barker Center, 12 Quincy Street, Cambridge, MA

Date/Time: November 13, 2013 - 12:00pm

S.T.E.M. with no root bears no fruit: Colloquial appropriations of canonical science through hip-hop education

In this presentation, HHARI Fellow Professor Emdin explores the ways that hip-hop culture, particularly the words, phrases, expressions, and language of its cultural ambassadors (hip-hop artists), expresses an interest in, admiration for, and in some cases, deep knowledge of science that goes unnoticed by educators who are not deeply immersed in black popular culture. Professor Emdin conducts an excavation of science themes within contemporary urban Black popular music and culture, and explores the ways that these themes can be used as pedagogical tools to bridge the divides between “non academic” hip-hop language/cultural understandings and canonical academic science. In particular, Emdin showcases approaches to teaching and learning that draw from Black culture and showcases how and why they have the potential to transform education.

Christopher EmdinAssociate Professor of Science Education, Teachers College, Columbia University

Introducer: Laurence RalphAssistant Professor of African and African American Studies and Assistant Professor of Anthropology

Lecture is free and open to the public. There will be a Q&A session following each talk. Please feel free to bring a lunch.

Published on November 12, 2013 02:44

November 11, 2013

12 Years a Slave and the Problem of (Black) Suffering by Rebecca Wanzo

12 Years a Slave and the Problem of (Black) Sufferingby Rebecca Wanzo |

HuffPost Black Voices

12 Years a Slave and the Problem of (Black) Sufferingby Rebecca Wanzo |

HuffPost Black Voices

I keep reading these blogs about Steve McQueen's 12 Years a Slave claiming that black people are "tired" of seeing yet another slavery movie. Message board comments tell me that some non-black people are tired too, but these people are those who don't understand why a majority of African Americans are inexplicably still a little troubled by slavery, Jim Crow, and ongoing inequality in labor, housing, education, and the criminal justice system. Go figure.

Maybe I know what they mean. After all, we have all those movies about well-known leaders who were slaves like Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, David Walker, Nat Turner, Sojourner Truth, Denmark Vesey... hmmmm. Not so much?

Then I guess they are just tired of all the stories about slavery that show the variety of experiences that took place over 250 years in the United States. I mean, there are at least as many films about slavery as there are about World War II, cowboys in the nineteenth century, or white people during the Civil War, right? What? You mean there's not?

Thus the claim that people are "tired" of seeing slavery is fairly indefensible in relationship to the number of other historical genres that have many notable films. I would think that an institution that was immeasurably important in shaping our national history, demonstrating the greatest evils, tragedies, and resilience that we could possibly imagine, would garner a few more notable films than Mandingo, Beloved, Django Unchained, and McQueen's recent entry into the slave film "genre." Sure, there are a few more (and while it was on television, we must include Roots in this discussion), but given the number of people who were enslaved and the number of stories that nobody knows about, we have hardly cracked the surface of tales that could be told.

This argument is thus a bit baffling. Except it's not. And it isn't baffling because we have issues in this country with telling stories of suffering that don't result in uplift.

Critic after critic focuses on how it's just too much suffering: "It is torture porn." "Why doesn't Hollywood ever want to fund other stories about African Americans that don't involve suffering?" "Why do white people just love to see brown people subjected?"

There is no question that we need a greater variety of representations of African Americans and many different kinds of people in Hollywood film. It is always fair to ask questions about why certain films get made and others do not. But we owe it to McQueen's film to evaluate it on its own terms, and not use it to complain about all the other films that don't exist.

The principle complaint about this film is that the suffering is relentless. And it is. McQueen's narrative leaves out a great deal of slave history (did I mention that we're talking about 250 years?) This is not a film about black resistance. Or the ways in which slaves found joy and community with each other. This film is a meditation on the meaning of slave suffering. After telling the audience the year early in the film, 12 Years a Slave does not give us many clues about the passage of time, or the relief of periodic dates to keep track of when freedom will inevitably come. Time is marked by shifts to different plantations, gradual graying and the haggard appearance of the protagonist, Solomon Northup, and above all, long scenes of the body in pain. I don't think another film about slavery tries to demonstrate conceptually how human beings are, as Elaine Scarry has described it, unmade by pain. It is not entertainment, but it is an artistic rendering that attempts to get the audience to see the passage of time, and the transformation of the body and human spirit under torture, in a new way.

And in McQueen's choice to focus so intently on the story of a slave woman named Patsey, Northup's salvation -- which we know is coming from the title -- does not provide the typical Hollywood uplift. If the audience forgets her cries, still ringing in their ears when Northup sees his family again, they weren't paying attention. The accusation that it is torture porn ignores the fact that pornography is supposed to result in an orgiastic catharsis. The cheers and glee accompanying the rhythm of contemporary torture porn films like Saw, the cheering that accompanies the violence in cartoonish superhero films, and the tear-soaked sentimental catharsis of The Help are not to be found here. While it is always difficult to make claims about audience response, I would suggest that the rhythm of this film leaves you too exhausted to rejoice. There is no John Williams score rising up, as it does at the end of Schindler's List, that allows the audience to cheer the goodness of a savior. People comment that 12 Years a Slave is brutal, that they are wrung out, and that it leaves them broken. It is supposed to.

While not made as a response to Quentin Tarantino's Django's Unchained, it is an important response to the deeply conventional Hollywood narrative of that film. Django is an example of the exceptional Negro that proves the rule that real men can rise up and overcome any oppression. And in the narrative logic of the film, the climax, which always involves the death of the most villainous character, doesn't involve killing the slave owner. No, it involves killing the Uncle Tom character, who was actually the one responsible for overseeing Django's fall and torture. Black people, in Django, keep themselves down, and just need inspiration to lift themselves up.

The real Solomon Northup also resists slavery, and in an interminable scene, they break him. What does it mean that in the logic of so many narratives of masculinity, that makes him less of a man?

Racist resistance to representations of black suffering and anti-racist criticisms of representations of black suffering are actually two sides of the same coin. Producers of both discourses internalize a cultural discourse that sees representations of adult victimization as somehow less artful and distasteful.

Looking away has become a national pastime -- from the poor, the sick, and the civilians killed by war and drones. It is unclear to me what kinds of representations of suffering can always escape condemnation as sentimental, or manipulative, or "suffering porn." But when we disparage 12 Years a Slave for trying to capture the essence of pain in chattel slavery, we are disavowing people whose pain can never totally be represented. There are, of course, other stories about slavery and black people that can and should be told. But that does not lessen the importance of this one.

***

Rebecca Wanzo is Associate Professor of Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies at Washington University in St Louis. She is the author of The Suffering Will Not Be Televised: African American Women and Sentimental Political Storytelling.

Published on November 11, 2013 19:04

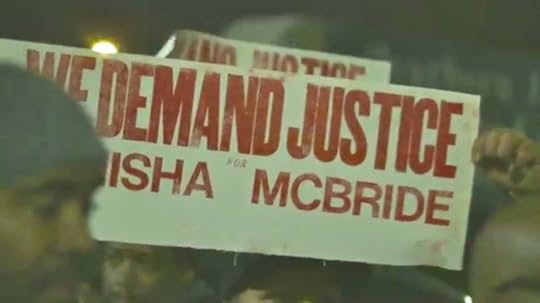

For Renisha McBride and Us by Raygine Diaquoi

For Renisha McBride and Us

by Raygine Diaquoi | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

For Renisha McBride and Us

by Raygine Diaquoi | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)I cannot remember a time when I was unaware of the fact that I lived in a world that is defined by anti-blackness. As a very young child, I would have the same recurring dream. Often, I would find myself hiding in a market place that sat at the edge of the water. Many crates filled with melons were arranged in neat rows. Sometimes, tall green stalks of freshly cut sugar cane, bound together in tight bundles, stood up against the crates as if they were bodyguards for the melons. It was warm in the market place, so warm that I would often wake up sweating.

In the market I was always crouching behind one of the crates and watching the people, who were all family members and friends, mill about hurriedly. Suddenly, brown and black men in neatly pressed olive green military uniforms, olive green caps and unusually shiny black boots, would march into the market. They brandished large rusty machetes and machine guns, slashing and shooting so quickly that the whole thing would always end before I could really see what was happening.

When the dust cleared I would emerge from behind a crate to see a macabre scene: bodies and melons, with their red insides spilling out onto the brown dust.

My own screaming and crying would wake me up. I would run downstairs to ask my grandmother to make phone calls to confirm that the people who had died in the dream were still alive in the waking world. Though my grandmother tried to soothe me by reminding me that it was only a dream, the heaviness in her face suggested otherwise. We both knew that while it wasn’t my present reality, it was a reality. I would hear her discussing the dream in hushed tones with my mother. The scene haunted me throughout my childhood and early adolescence. I couldn’t make sense of it. I didn’t know where or when it was coming from. I would walk around for many days after, silently mourning the deaths of those people in the market place.

When I was in college, I recognized the marketplace that I had been dreaming about for years in reading about the massacre that occurred in 1937 in the market town of Dajabón, which lies on the border of Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

In what would be the beginning of a series of acts fueling Dominican anti-Haitianism and anti-blackness, Dominican dictator Rafael Leonidas Trujillo Molina, ordered soldiers to kill between 15,000 and 30,000 ethnic Haitians, who had been born and had lived in the Dominican Republic for generations, while they attempted to cross what is now known as the Massacre River (Turits, 1998). In the dream, I am never among those who are running. I am always watching, seeing the hate in the eyes of the soldiers who are bent on annihilating blackness, theirs and that of the people in the marketplace. I think that my inability to act despite my knowledge of how the attack would end was what really made me scream and cry after each dream.

My grandmother was 8 at the time of the massacre, about the same age that I was when I started having these dreams, and living in Haiti. While neither she nor my parents ever discussed this part of Haitian and Dominican history with me, I lived it every night for several years throughout my early childhood and into my teen-age years.

I have since learned that while this history was not taught explicitly within schools, many Haitians were aware of it at the time, had many conversations about the massacre in their homes and communities and continue to, both consciously and unconsciously, pass the story down to future generations. Though my parents had never discussed the massacre with me, in second grade, I found myself linked to the trauma and unconscious of an entire people even though I lived many miles and years away (Freud as cited in Eng, p.167, 2001). I could not explain it then but I knew that these histories were a part of me, a living and complex part of me and that I was a part of these histories. I now understand my ability to rememory the past, a concept brought to us by Toni Morrison, to be a part of my unique ontology as an American African, a way of being that belongs to all of us.

From this recurring dream, my rememory of past injustices, I know that our red insides will continue spilling onto the brown dust if we continue to crouch silently behind our individual crates, passively watching and then actively forgetting this American nightmare. We’ve disremembered our past and forgotten that we are at Massacre River. We’ve forgotten that we live in a world that is defined by anti-blackness, missing the implications of the message of the current moment for the future and failing to recognize, in this present moment, lessons learned from a very recent past.

The late critical race theorist, Derrick Bell, reminds us that, “Black people will never gain full equality in this country. Even those herculean efforts we hail as successful will produce no more than temporary "peaks of progress, " short-lived victories that slide into irrelevance as racial patterns adapt in ways that maintain white dominance. This is a hard-to-accept fact that all history verifies. We must acknowledge it, not as a sign of submission, but as an act of ultimate defiance.”

For Renisha McBride and us.

***

Raygine Diaquoi is a critical race theorist and graduate student at theHarvard Graduate School of Education where she is completing a dissertation on African American children. You can follow her on Twitter: @CounterNarrativ

Published on November 11, 2013 05:31

November 10, 2013

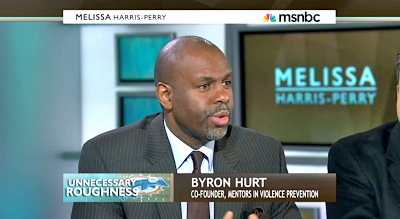

Filmmaker Byron Hurt Talks Bullying and Hazing on the MHP Show

MHP Show

MHP ShowDocumentary filmmaker and activist Byron Hurt joins “MHP” to discuss the NFL bullying controversy and his new film about the spread of hazing in America.

Published on November 10, 2013 18:11

November 9, 2013

Dialogue: bell hooks and Melissa Harris Perry [video]

MHP Show

MHP ShowMelissa Harris-Perry has a conversation with famed author bell hooks on the evolution of the black feminist movement in America.

Published on November 09, 2013 18:29

"We Demand Justice for Renisha McBride" [video]

Published on November 09, 2013 18:09

Adrienne Davis--Slavery: Beyond the Pure Property Paradigm [Lecture]

Duke Law School

Duke Law School"What, precisely, is the legal evil of slavery?" Adrienne Davis, the John Hope Franklin Visiting Professor of American Legal History examines this question and other aspects of slavery's intersection with law when she delivers Duke University's annual Robert R. Wilson Lecture. Professor Davis is visiting Duke Law during the fall 2013 semester from Washington University in St. Louis, where she is Vice Provost and the William M. Van Cleve Professor of Law.

Published on November 09, 2013 17:55

"The NFL's Bully Problem": Sports Columnist Dave Zirin Connects Violence in Sports to Rape Culture

Democracy Now

Democracy NowThe National Football League's culture of violence has come under scrutiny after Miami Dolphins player Richie Incognito allegedly made bullying and racist threats to his teammate Jonathan Martin. We talk with Dave Zirin, The Nation sports editor and host of Edge of Sports Radio who explains: "Think about other stories that have been in the media recently with names like Steubenville, or Maryville, or Torrington, Connecticut, instances where you see this connective tissue between jock culture and rape culture, all of these things are very connected. This idea where you get young men in a very violent kind of group mentality ... It creates a very, very destructive social climate that puts terrible social cues out to the general public."

Published on November 09, 2013 17:34

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.