Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 852

December 6, 2013

Madiba, Peace at Last--Mandela: A Long Walk to Freedom

Madiba, Peace at Last

--Mandela: A Long Walk to Freedom

by Stephane Dunn | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Madiba, Peace at Last

--Mandela: A Long Walk to Freedom

by Stephane Dunn | NewBlackMan (in Exile)Sometimes I love irony because it reminds me to pay attention to the gift of remarkable moments. So recently, I’m honored enough to host a public chat after a movie screening and the film is Mandela: A Long Walk to Freedom. The next day, December 5, 2013, I’m sitting in front of the television catching up on the news and I go to turn it off because I’ve got to write my review of the film from the previous night but before I press POWER, South African President Jacob Zuma announces to the world: Nelson Mandela is now at peace. And right then I laugh and sniffle and it’s not all grief; it’s joy and thanks and a spirit of reverence.

I flash back to remembered scenes, Free Mandela rallies, an episode of A Different World when the students at fictional HBCU Hillman debate how to best protest against companies investing in South Africa. And then last night, the final note of the Mandelapanel – that when he passes, as we all knew of his frail health – that the world take the time to pause, take notice and ponder his legacy. Mandela: A Long Walk to Freedom is poised to lead that pause. It is not a perfectly balanced film, but it is an emotionally impactful film and with perfect timing and an extraordinary subject, ultimately memorable.

Mandela, based on Mandela’s autobiography, takes it place within the impressive South African filmogaphy of producer Anant Singh (Place of Weeping, Sarafina, Cry the Beloved Country). A South African himself, Singh worked some nineteen years on Mandela with Nelson Mandela’s blessing. The end result of this mighty and long effort is a film that does not merely chronicle the life of a singular iconic figure but which undertakes the herculean work of representing a nation and a people’s long and bloody struggle to end racial apartheid and create a new South Africa. Mandela, directed by Justin Chadwick and starring Idris Elba in an Oscar buzz worthy turn as Mandela and a stunning Naomi Harris as Winnie Mandela, accomplishes several key feats, not the least of which is somewhat demystifying the iconic moment people might recall in February 1990 when Mandela ‘walked’ out of prison after twenty-seven years by first not ending the film with that moment and secondly offering insight into the political maneuvering and long process preceding Mandela’s release, including his secret parlays with government officials representing President de Klerk.

We also get a glimpse at the bond between Mandela and his fellow life imprisoned African National Congress comrades who disagreed with Mandela’s efforts at negotiating with the enemy. Mandela also does well too in delving into the immediate aftermath of his release as violence tears apart the country amid a battle for power against the Afrikaner controlled government and between blacks within and outside the organization as they are torn over how to achieve power – violence or not and how - and whether or not to share it with the Afrikaners who had for so long maintained a brutal, total system of oppression.

We also get a glimpse at the bond between Mandela and his fellow life imprisoned African National Congress comrades who disagreed with Mandela’s efforts at negotiating with the enemy. Mandela also does well too in delving into the immediate aftermath of his release as violence tears apart the country amid a battle for power against the Afrikaner controlled government and between blacks within and outside the organization as they are torn over how to achieve power – violence or not and how - and whether or not to share it with the Afrikaners who had for so long maintained a brutal, total system of oppression. The film tries hard to invoke the sense of the collective nature of the anti-Apartheid movement, mostly through a collage of images, crowds of black South Africans fists raised around Winnie Mandela, chanting outside the courthouse where Mandela and his comrades are tried and sentenced, and later shots of brutal mass killings post Mandela’s release. Chadwich relies quite a bit on representing the collective body of South African protesters through, as is often the case in films seeking to represent a movement in it’s time, a fast paced collage of images, creating a newsreel. This can cover a lot of ground and help to convey the intensity of the revolution and underline its historical import, but it also unfortunately frames the people and their story through the same generic distillation that happens in news media from outside.

The endlessness of time – twenty-seven years in prison and more years of the struggle – is the other central element in the history of Mandela and the revolution that the film struggles to pull off here too relying on a staple of narrative film – the expert artistic aging of characters. There is something unsettling about that, robust, black haired men in their prime suddenly grey then suddenly more grey and frail. This visual appearance aims to suggest the passage of time, hard time, but doesn’t convey adequately the horror of that seemingly endless everydayness of imprisonment. The touching scene between Mandela and ZindZi visiting her father for the first time on Robben Island and the death of his first-born son whom he is denied permission to bury are exceptions.

But perhaps the most poignant achievement of the film is the intimate peak into the relationship of Nelson and Winnie Mandela from its inception, on the heels of the demise of his first marriage, through courtship and the destruction of a great love and a marriage as both are persecuted for their unyielding commitment to the struggle for freedom. It’s painful to watch that great toll on Winnie, Nelson, and their children as well as Mandela’s previous family. But this is also where the film turns to developing a problematic portrait of Winnie Mandela. Winnie is jailed, separated from her daughters, and tortured after her husband is sent to Robben Island; the film situates this as the catalyst for her transformation, not into a radical activist and political strategist but militant avenging baadasss who leads the ANC and the younger generation into mere violent chaos.

Naomi Harris invokes the resiliency of Winnie Mandela and her fighting spirit in the set of the shoulders, the rage, brave defiance, and pain she displays while being tortured by her captors but coming out resilient and more determined to fight against the oppression of her people. It is not difficult to understand Winnie Mandela and her daughters approve Harris’s performance. Harris visited with Winnie Mandela and her two daughters while preparing for the role.

Yet, the film falls short in treating the vastly more complicated character, role, and brilliance of Winnie Mandela, and her relationship to the people especially young South Africans who identified more with her than Nelson Mandela. Winnie Mandela’s controversial role in the revolution and her reported involvement in orchestrating the violence during it render her a much more challenging figure to perhaps adequately represent as she is not the globally iconized, undisputedly saintly figure that Nelson Mandela became.

However, she was instrumental in keeping his name and sacrifice alive during his years of imprisonment. There is little treatment of her years of long confinement under house arrest. She is simply a woman robbed of all humor, gone emotionally cold. Nelson Mandela is intellectuality, rationality, and nobility while Winnie, is uncontrollable emotion – a fanatic, avenging vigilante, ball of rage, and essentially an angry black woman bent on revenge rather than justice. She gets in the way of the men [white and black], attempting to reasonably negotiate terms for achieving peace and the transition in power.

The portrait of Winnie Mandela teeters into caricature as she’s reduced to a sort of Black Power-esque diva fierce face, raised fist, afro and what appears to be paranoia rather than justified questioning and suspicioning of the Afrikaners overtures to her husband. Alongside her regal husband winning over whites and the world by seeking peace and exhibiting only love and patience towards all, Winnie Mandela’s main role in the film becomes to function as the antithesis of her husband’s right way to a new South Africa. Other women, the few seemingly important enough to depict, don’t fare too well either, as Nelson Mandela’s first wife Evelyn is treated unsympathetically as merely incapable of understanding and supporting his involvement in fighting against apartheid. Still, Mandela: A Long Walk to Freedomis a significant film, even more so now as it will help to do the work of keeping this history alive presently and in the future. The film concludes after the official end of the total political domination of the Afrikaners with Nelson Mandela’s voice. The story of apartheid’s difficult legacy continues in South Africa, but Mandela: A Long Walk to Freedom effectively invokes the wondrous spirit of Madiba and the resiliency and collective move***

Stephane Dunn, PhD, is a writer who directs the Cinema, Television, & Emerging Media Studies program at Morehouse College. She teaches film, creative writing, and literature. She is the author of the 2008 book, Baad Bitches & Sassy Supermamas: Black Power Action Films (U of Illinois Press). Her writings have appeared in Ms., The Chronicle of Higher Education, TheRoot.com, AJC, CNN.com, and Best African American Essays, among others. Her recent work includes the Bronze Lens-Georgia Lottery Lights, Camera Georgia winning short film Fight for Hope and book chapters exploring representation in Tyler Perry's films.

Published on December 06, 2013 05:24

December 5, 2013

Rape, A Loaded Issue for Black Men: on Jameis Winston

Rape, A Loaded Issue for Black Men

Rape, A Loaded Issue for Black Men

by Byron Hurt | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

One of the most stressful and challenging conflicts that affect me during a rape case occurs when the alleged perpetrator is a Black man. As one of many Black males who consistently speaks out against all forms of violence against girls and women, I'm always torn and somewhat hesitant to take a strong stance or make an early rush to judgment.

The pushback that I receive from other Black men can be swift and strong. This country's history of Whites falsely accusing Black men of raping White women - only to be proven innocent years after they've paid a heavy price - makes it difficult for many Black men to believe allegations of rape, especially when the victim is White.

Countless Black men, like Alabama's the Scottsboro boys, Chicago's Emmett Till, the Central Park Five in New York City, and more recently Brian Banks in Atlanta, GA, have shamefully suffered the injustice of a racist criminal justice system that rushed to judgment, with little or no evidence. As a result, numerous innocent Black men were executed or and sent to prison to serve long sentences.

White men who do anti-sexist work may know and understand this history, but they probably don’t share the same tension I feel. I'm sure that my Black brothers who do gender violence-prevention work better understand this inner battle. The dynamics always become a little more complicated when it comes to Black men and rape.

Even more complex is having conversations with other Black men who believe in their hearts that the victim is lying, or that the Black man is being framed – a highly sensitive issue amongst us Black men. However, it must be said, without equivocation or cowardice, that Black men, like all men, do commit rape against women. We live in a rape culture that transcends race.

Tragically, men from every racial, ethnic, cultural, and socioeconomic background perpetrate acts of sexual violence that hurt and traumatize women – including Black women. We must address rape with honesty and with courage and must not be dissuaded by pushback, denial, or defensiveness by Black men or any other group of men.

When a high-profile athlete like Jameis Winston is accused of rape, I force myself to separate my love for him as a quarterback and open myself up to the possibility that even though he is an outstanding football player worthy of this year's Heisman Trophy, he may, in fact, be a rapist.

Please, lower your defenses and hear me. I totally understand that Winston has not been charged with a crime. I understand that he is a frontrunner to win the Heisman. I know you may want to see him and his teammates at Florida State University compete for the national championship. I'll be the first to admit that I enjoy watching Famous Jameis play on Saturdays.

But we must resist the temptation to assume that Jameis Winston falls into the category of Black men who have been falsely accused of rape – a lamentable historical pattern. To do so would be unfair to the rape victim. We shouldn't automatically assume that he did not commit the crime because he is being set up, or that his team's championship season is being sabotaged, or that there is a witch hunt against Winston and his Heisman campaign.

It is true that Black men continue to be cruelly stereotyped as rapists. As a Black man, I carry that label – and all of the other stereotypes associated with Black men – wherever I go in our country. However, it is also a stereotype that women lie about being victims of rape more often than not. According to FBI statistics, less than 3% of all rapes are falsely reported.

I also know what my reaction would be if my daughter approached me and told me a boy or man raped her. Race, class, social standing in the culture would mean nothing to me. My only concern would be to ensure that my daughter felt supported and safe, and that she began the healing process from her pain and from her trauma. Beyond that, I would expect the perpetrator to be punished to the full extent of the law and would advocate for him to receive extensive gender violence prevention training in prison.

That's tough to say if you believe that most women lie about rape. If your defenses are up, you are resistant to hearing the truth, or you've been scarred by history, you won't hear the voice of a fellow Black man.

Going back to the premise of this piece, when you are a Black man and you speak out against the sexual violence of other Black men, it can feel completely isolating and lonely. Your racial loyalty and your manhood get called into question by other Black men.

What Black man would go out of his way to have his Blackness and his manhood challenged by his Black brothers? What Black man wants other Black men to lose respect for him? What man wants to be dismissed, or have his man card revoked?

I don't. But I also want to be fair, and compassionate, and supportive to victims and survivors of rape, no matter who their rapist is, or what he looks like. And ultimately, I want be on the right side of justice.

What kind of man wouldn't want that for his own daughter?

***

ByronHurt is award-winning documentary filmmaker, writer, lecturer, and anti-sexist activist. He is currently working on his next film, Hazing: How Badly Do You Want In? Email him at byronhurt@bhurt.com. Twitter: @byronhurt.

Published on December 05, 2013 04:58

December 4, 2013

'Reframing Black Masculinity'—Mark Anthony Neal on HuffPost Live with Marc Lamont Hill

Reframing How Black Masculinity Is PerceivedMark Anthony Neal, professor of Black Popular Culture at Duke University, joins Marc to discuss his new book, "Looking For Leroy: Illegible Black Masculinities" about how Americans have stereotyped African-American males.

Reframing How Black Masculinity Is PerceivedMark Anthony Neal, professor of Black Popular Culture at Duke University, joins Marc to discuss his new book, "Looking For Leroy: Illegible Black Masculinities" about how Americans have stereotyped African-American males.Originally aired on December 3, 2013Hosted by:

Marc Lamont HillGuests:

Mark Anthony Neal @NewBlackMan (New York, NY) Professor of Black Popular Culture at Duke University

Published on December 04, 2013 04:55

December 2, 2013

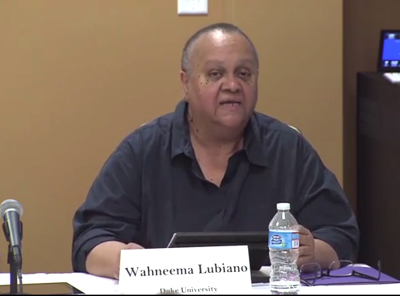

Wahneema Lubiano Debunks the Term "Black on Black" Crime

Duke Forum for Scholars & Publics

Duke Forum for Scholars & PublicsWahneema Lubiano, speaking at Duke's "National Dialogue on Race Day," offers a critique on the term "Black on Black Crime." In Fall 2013, the Center for Study of Race and Democracy at Tufts University partnered with Duke University for the first annual "National Dialogue on Race Day." The panel was co-hosted by Duke's Forum for Scholars and Publics and African and African American Studies.

Published on December 02, 2013 20:06

Playing Field to Prison Pipeline?

Hank Willis Thomas--"Strange Fruit"

Playing Field to Prison Pipeline?

by David J. Leonard | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Hank Willis Thomas--"Strange Fruit"

Playing Field to Prison Pipeline?

by David J. Leonard | NewBlackMan (in Exile)In our contemporary moment, sport does much of the ideological work of mass incarceration. Even more than others forms of popular culture, which peddle in racial stereotypes, celebrate law and order, and turn police into righteous crime fighters, sports has increasingly become a space that is central to maintaining America’s prison nation. Because of the visibility and cultural resonance of sports, because of the number of African Americans involved in professional sports, and because of the centrality of “American Dream” narratives, sports serves as the public relations wing of mass incarceration.

None of this should be surprising given the racist nature of America’s criminal justice system, and the centrality of race within contemporary discourses. Public discourses around sports and criminal justice center race.

Writing about basketball, Todd Boyd argues that the NBA “remains one of the few places in American society where there is a consistent racial discourse,” where race, whether directly or indirectly, is the subject of conversation at all times (Boyd 2000, p. 60). This is equally resonant with football and therefore it is not surprising that racialized conversations of sports and the criminal justice inform one another.

Of course this is nothing new. According to Elizabeth Alexander, the history of American racism has always been defined by practices where black bodies are put on display “for public consumption,” whether in the form of “public rapes, beatings, and lynchings” or in “the gladiatorial arenas of basketball and boxing.”

Jonathan Markowitz highlights ways in which the sports media contributes to the widespread criminalization of the black body: “The bodies of African American athletes from a variety of sports have been at the center of a number of mass media spectacles in recent years, most notably involving Mike Tyson and O.J. Simpson, but NBA players have been particularly likely to occupy center stage in American racial discourse.”

Whether through the media spectacles surrounding Tyson, O.J. Kobe Bryant, Aaron Hernandez and countless other cases, or the adoration and fear imbued in physical bodies (that which is desired on the field is also that which rationalizes mass incarceration, stop and frisk, and law and order), we see the convergence of the front and back pages.

Not coincidently, the increased focus on law-breaking athletes mirrors the integration of sports (and the rise of America’s prison nation). That is, as collegiate and professional sports became more integrated, sports media and fans began to show an increasing concern about “criminal athletes.” This is especially the case in a post-1980s context, whereupon President Reagan seized upon the death of Len Bias to expand the racialized war on drugs.

Since then, and with proliferation of ESPN industrial complex, there has been an immense focus on crime and athletes, giving credence to the widely circulated ideas about the pathology of blackness. The shared language of “discipline” and the administering of punishment for those who violate the rules of society/sports further illustrates the convergence of the sports and the (in)justice system.

If sports are central to the prison industrial complex, ESPN represents the CEO of its public relations firm. Given the longstanding role of the Disney Corporation in circulating dehumanizing images, it should be of little surprise that ESPN is doing the ideological grunt work of contemporary racism and mass incarceration.

Whether it be publishing articles about drugs and Oregon football, or sensationalizing each and every traffic stop involving a (black) athlete (never mind issues of pretext stops and racial profiling) or becoming the mouth piece for bringing law and order to a post-Palace Brawl NBA, ESPN has been a willing partner in the prison industrial complex.

In recent weeks, ESPN has turned this job over to Jason Whitlock. This is the same man who once refereed to Serena Williams as an “unsightly layer of thick, muscled blubber, a byproduct of her unwillingness to commit to a training regimen and diet that would have her at the top of her game year-round.” Fear and loathing of black youth jumps off his pages; the same sort of stereotypes and narratives that rationalize stop and frisk, and shoot first mentality that plagues this nation.

The sustained nature of Whitlock’s discussion of personal/communal/cultural failures and mass incarceration (see Whitlock Gone Wild), raises the stakes here. For example, in a recent column on Thanksgiving (never mind the history of genocide and white supremacy), where Whitlock denounced Professor Michael Eric Dyson, he once again peddled his simplistic vision of the world: the personal and cultural failures of African Americans, facilitated by intellectual and cultural enablers, has led to mass incarceration.

And while Mr. Whitlock wants to locate mass incarceration at the doorstep of hip-hop culture, at the feet of Jay Z, Allen Iverson, and Michael Eric Dyson, he is asking us ignore history. He wants to erase the linkages between mass incarceration and the history of slavery, between white supremacy, “Black Social Death,” and America’s prison system. In turning the discussion into choices, values (respectability), culture, single-parented homes, and bad role model, he denies the links between deindustrialization and expansion of prisons, between the militarization of America’s police forces and the number of African American youth locked up.

As I read column after column that blames hip-hop or the N-Word for mass incarceration, I cannot help but wonder if Richard’s Nixon’s launching of the war on drugs, if the Rockefeller laws, the federal sentencing guidelines for crack, the disenfranchisement laws that saturate our nation, the centrality of racial appeals for law and order, President Bill Clinton’s massive expansion of America’s prison system, and the he investment in police and not schools, was all because of hip-hop. If you live in Jason Whitlock’s world, and that of the vast number of celebratory commentators, that seems to be the conclusion.

***

David J. Leonard is Associate Professor in the Department of Critical Culture, Gender and Race Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. Leonard’s latest books include After Artest: Race and the Assault on Blackness (SUNY Press) and African Americans on Television: Race-ing for Ratings (Praeger Press) co-edited with Lisa Guerrero. He is currently working on a book Presumed Innocence: White Mass Shooters in the Era of Trayvon about gun violence in America.

Published on December 02, 2013 19:48

Pardoning Turkeys, Not People? Obama Urged to Reverse Lowest Clemency Rate of Modern Presidency

Democracy Now

Democracy NowAs President Obama continued a recent tradition of granting a presidential pardon to a pair of turkeys just ahead of Thanksgiving, critics pointed out that he has shown less mercy towards human beings deserving of clemency. Despite the administration's recent talk of reforming the criminal justice system, Obama has granted the fewest pardons of any modern president. During his presidency, Obama has pardoned 10 turkeys, while he has pardoned or commuted the sentences of only 39 people.

Published on December 02, 2013 12:10

December 1, 2013

A Man at His Peak?

Gary Simmons--"Step into the Arena"

Gary Simmons--"Step into the Arena"A Man at His Peak? (with a nod to my first and favorite poet Nadine Turner) by Mark Anthony Neal | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Ain’t no nuance about this—I wasn’t supposed to make it to 48, and none of the data would suggest that if I did make it to 48, that I would do and thrive. The tale of a Black male, born and raised in working poor urban America, where if the random violence of the ‘hood didn’t catch us by age 18, then the heart disease, hypertension and still random violence would surely catch us by 50 is all too real.

I know I’m blessed.

But this ain’t a time for meekness.

If December 2, 2013 marks the end of my 48th year on this earth, I’m stomping into year number 49.

At 48, my father was recovering from a pedestrian accident that put him on his ass, yet not only did he fight back, he would only a few years later claim his greatest success, finally grasping a piece of his American Dream, co-owning a restaurant in Crown Heights—however fleeting it was. When MS claimed his mobility (but not his mind) during those final 15 years of his life, he lived with it on his own terms.

At 48, my mother had transitioned from school lunch room to the classroom, with a Masters Degree in close view a few years down the road. She had achieved what her 16-year-old self would have never imagined, as she left her mother’s house in Baltimore and headed to New York City.

And at 48 my maternal grandmother, was just dusting off her heels, her life barely half over. The last day she walked the earth, she did so with five generations of her family walking the earth with her.

Fuck a mid-life crisis.

In my mind a mid-life crisis is trying to write four or five books in the next decade, like I was a cat just coming into this game at 28.

A mid-life crisis is the reminder that at 48, John Hope Franklin was about to go to the University of Chicago, with a dozen authored and edited volumes ahead of him, including the memoir that he dropped at age 90 in 2005—and he still had the energy and the passion to tour in support of its publication, while still driving his Lexus around Durham. Bawse.

And that don’t mean that the fear of death ain’t real.

Some of the greatest minds that I knew—Aaronette White, Clyde Woods and “the R”—Richard Iton—passed away well before their times. Aging gracefully is about living with the stark reality of your own mortality.

But we stomping today…

“Treat my first like my last, and my last like my first And my thirst is the same as when I came”…

and as long as I can climb up into my mind and build and create, we ain’t nowhere near our peak.

Stomping.

Published on December 01, 2013 20:14

Black Girls Code Series #1: The Revolution Will Be Mobilized

Black Girls Code

Black Girls CodeBLACK GIRLS CODE: THE SERIES is a unique documentary web series is meant to inspire.

Check out the new teaser from episode #1: THE REVOLUTION WILL BE MOBILIZED.

Founded by Kimberly Bryant, Black Girls Code is a unique non-profit that introduced young girls of color into the fields of STEM.

Support & Join the MOVEMENT OF BLACK GIRLS CODE. They are creating the future pioneers of our generation.

Support Black Girls Code @ BlackGirlsCode.com

Series directed by Shanice Malakai Johnson

MalakaiCreative.com

Published on December 01, 2013 18:50

Making a Scene: Michael B. Jordan

New York Times Video

New York Times VideoThe year's best performers star in 11 original (very) short films directed by Oscar-winning cinematographer Janusz Kaminski.

Published on December 01, 2013 18:35

Tell Me More: Blitz the Ambassador on Hip-Hop in Ghana & 'Afropolitan Dreams'

Published on December 01, 2013 07:48

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.