Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 835

March 4, 2014

Producer 9th Wonder Breaks Down the Music Industry vs Education

1Hood Media

1Hood Media

9th Wonder sits down with 1Hood Media Academy participant K-Rocz to talk about the effect of the music industry and education in part three of his interview. Directed by Paradise Gray. Edited by HauteMuslim.

Published on March 04, 2014 04:58

March 3, 2014

No Final Redemption? Fruitvale Station and the Academy’s Ambivalence with Black Death

No Final Redemption?

Fruitvale Station and the Academy’s Ambivalence with Black Death

by Usame Tunagur | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

No Final Redemption?

Fruitvale Station and the Academy’s Ambivalence with Black Death

by Usame Tunagur | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)The 86th Academy Awards have been presented; As Gravity went home with 7 Oscars, 12 Years a Slave won 3 Oscars: Best Film, Best Adapted Screenplay and Best Supporting Actress. When the film first opened in theaters, Stephane Dunn said, “12 Years a Slave is decidedly not Django and not slavery light.” In spite of being a heavy, intense, and an intensely violent –both physical and psychological–film, 12 Years at the end has redemptive value, in that, Solomon Northup finds freedom after 12 years of brutal bondage. Film's resolution of Northup's eventual liberation, with the help of Brad Pitt's character, Bass, provides the audiences (particularly white viewers) a sense of redemption, hope, and a feeling of “pastness;” A feeling that we are past that horrible timeframe and have arrived in this space that should be considered post-racial.

2013 has witnessed another poignant film that engages race and justice head on: Fruitvale Station. However, the Academy did not even nominate this film in any category. So, one wonders if it was only because of how the Academy voted on its creative, narrative or technical value, or if it could be ascribable to another reason. Up-and-coming filmmaker Ryan Coogler's feature debut has already received numerous critical acclaim: Grand Jury Prize and the Audience Award for U.S. Dramatic film as well as Best First Film in Cannes' Un Certain Regard Section. Akin to Academy's nod to Beast of the Southern Wildwhile turning a blind eye to another masterpiece, In the Middle of Nowhere, Fruitvale received no love or appreciation from the Academy who has awarded 12 Years in three and nominated it in nine categories.

Could this omission stem from the fact that even though both films are based upon true stories of racial inequality and injustice, that Fruitvaledoes not offer a final redemption or relief to its audience in the face of such obvious contemporary violation of rights?

Fuitvale is clearly not a redemptive story. It is the story of Oscar Grant who was murdered on the first day of 2009 by a BART officer on the Fruitvale Station while returning from celebrating the New Years Eve with his girlfriend and other close friends. The film dramatizes Oscar's last 24 hours. It is not only based on a true story but the content is not older than five years. At the end of the film, Oscar Grant is murdered by a BART officer, becoming yet another young black male statistic in the drastic report prepared by Malcolm X Grassroots Movement highlighting the extrajudicial killings of a black person every 36 hours. The film successfully humanizes a young black male character –a rare attempt– and strongly challenges the audience about our legal system. Having been through the Prison System, Oscar tries to put his life back together; To be a better father, partner, son, and to keep his job – challenges anyone can relate.

In the beginning of the film, we see Oscar, after dropping his daughter to day care, calling his mom on the phone while listening to what some might consider “thug music” in a car that might look like to some as a “thug car” all the while wearing a hat and a long white tee – regularly associated with “thug-ness.” These associations from skittles and ice tea to “thug music” are not innocent; And they have consequence., So, when a film like Fruitvale offers a normalizing lens into the experiences of people who are more often than not only engaged or viewed as a list of shorthand associations with violence, laziness, and improper behavior, such a projection becomes both valuable and challenging.

It is with this type of appreciation that acclaimed filmmaker Ava Duvernay, in a Filmmaker Magazine interview with Coogler, celebrated this scene where Oscar Grant calls his mom, professing,

for me, to see a film in the context of Sundance, where I saw the film, I literally look around me, and it’s filled with white people seeing that same image that I see every day. I know they see it too. But now they have knowledge and context for what that brother’s day was like before that moment. Where you just see some hood in the car with the music up? No. He has a daughter. He has a mother. He has bills. He has worries. He has blood in his veins.

When the audience connects with its characters through a shared humanity, then the audience becomes receptive to the effects and outcomes of abuses of state power, prison industrial complex, and maybe most importantly our desensitization towards these real events and hard issues. This is rare and powerful; This is one of those rare moments where art can also move hearts and minds regarding policy. And, such a film totally deserves a nod from the Academy.

Coogler manages to keeps his audience wound up throughout the film, working them all the way up to the last moments of Oscar Grant. This process of keeping the audience wired is not an easy task for films whose ends are known. In that sense, both 12 Years and Fruitvale are very successful to keep their viewers engaged until the very end. It is particularly tough to maintain this tension in Fruitvale Station– as the audience knows very well what happens to Oscar at the end as the true events are freshly inscribed in their memory, especially through youtube videos of his last moments at the Fruitvale Station that went viral right after the murder and given the fact that most viewers watch this film right after weeks-long media coverage and the final verdict on the Trayvon Martin murder trial.

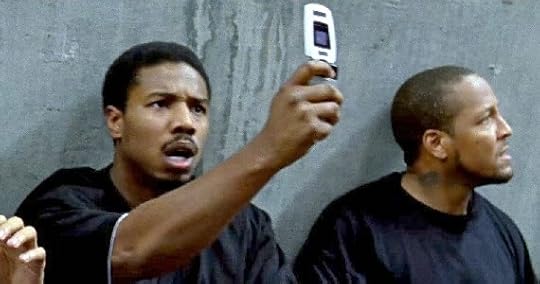

The most powerful and painful scene in Fruitvale also builds a visual bridge to 12 Years a Slave crossing over more than a century and a half. In this haunting scene towards the end of the film, the situation and position of the onlookers are particularly telling of our relationship with state power. As Oscar and his friends are pulled away from a subway train by BART officers and detained on the platform, all of the BART passengers are either looking with shock and fear, or shouting or some of them recording video with their cellphones. The scene is initially shot from the passengers' point-of-view, until the latter part of the scene. This P.O.V. brings us, the audience, to the crime scene as another set of on-lookers. This decision to cover the action from afar –through passengers' POV– reminds the audience of our “act of passive on-looking” to so many similar events of oppressions. As the audience, we are incapable (or decide to stay as such) as gross injustices are taken place literally right in front of us.

With the P.O.V shots, Coogler is replicating the angle of the cellphones that taped the moment –which then went viral on the internet and which motivated him in the first moment to write and direct this film. This also forces the audience to be on the field, almost feeling like we are witnessing this event here and now, providing a close proximity. And it is exactly the proximity of Oscar Grant murder both spatially and temporally that makes Fruitvale a tougher film for the Academy to recognize than 12 Years even though 12 Years has way more violence (both physical and psychological) throughout the film.

As clear and outward oppression is observed by on-lookers (and the audience) in this scene in Fruitvale, there is also a similar scene of a community observing–silently, powerlessly– another outright oppression and abuse in 12 Years. After finally reacting to the constant and jealous abuses of John Tibeats (solidly acted by Paul Dano) by beating him, Solomon is punished by being hanged with a noose on a tree while his toes are barely touching the ground. For a whole day until his master Ford (Benedict Cumberbatch) arrives, he stands and struggles between life and death, all the while the enslaved community goes about their chores, only staring at him for a few seconds –for fear of repercussion– with the exception of Patsy (played by now Oscar-winner Lupita Nyong'o) who only had the guts to quickly give him some water. In this scene, contrary to the above scene in Fruitvale, the audience is kept at a distance as the action plays out on a wide shot. We observe the torturous passage of time as Solomon tiptoes for his life. By keeping the audience at a distance, we are subtly reminded of the temporal and spatial distance between Solomon's reality, his context and ours.

Don't get me wrong; The scene is bleak, dark and gut-wrenching as time is working against Solomon. Furthermore, the inability of the others to help, adds insult to injury. The visible white supremacy throughout the film, is also active here invisibly halting anyone from even observing, yet alone helping Solomon–except for Patsy. True power of 12 Years lies in underscoring the psychological damage and oppression slavery caused for centuries. Scenes like forceful dancing, daily cotton reports, denial of one's own identity or knowledge, and montages displaying slow passage of torturous time create more of an impact than scenes of outright violence such as rape or beating.

One wonders if Hollywood would ever produce a film about slavery where it is not the story of Solomons who eventually find freedom– a general practice to redeem a film's narrative – but rather the story of Patseys who were born into, lived through and died under the bondage of enslavement. The answer in my humble opinion is that within Hollywood traditions, it is very rare to end a film with such a dark note where the protagonist(s) continue their bondage, challenging the viewers without much room for redemption. But it is not improbable, as independent films like Fruitvale show how it can be done, making them even tougher films to watch, but needed ones with lingering effects.

Tougher films have long shelf lives and they can seriously engage audiences to think, question, or at least feel uncomfortable, which sometimes can even result in attitude change. Such are examples of transformative art. Another question at hand is: do such films need recognition by the Academy? No film in and of itself need Academy recognition. If they are good, they will have an audience and stand for themselves. However, an Academy recognition means something. Take a film like Gravity. As it is nominated for 10 Oscar nominations, it's been re-released in theaters, and probably with 7 Oscars it will stay in theaters even longer. The same goes for 12 Years which has been re-released as well utilizing the positive wind of 9 nominations. An Academy recognition also has the potential to bring the issue or the theme of a film to national attention.

The Sundance recognition Fruitvale received cannot be underestimated which landed the film a Weinstein Bro's distribution deal which eventually released it in more than a thousand theaters. But, an Academy nod –not even the awards but at least a nomination– would have helped bring Fruitvaleto limelight and present the opportunity for more Americans to be engaged with an issue which is not going away – rather becoming grimmer and bleaker every day. Especially given the fact that the Academy has nominated 9 films for the Best Film award, Fruitvale could have been among one of those nine, or nominated for Best Original Script, Best Director or Best Actor categories.

Last night after the awards ceremony, on CNN, Piers Morgan asked the entertainment reporter on the field her initial reaction to 12 Yearswinning big. She mentioned how happy she feels and how 12 Years as a result should be included in schools' curricula. Imagine Fruitvale receiving such attention and being added to the educational curricula across the country. Maybe, if more kids watched Fruitvale along with 12 Years, it is possible in the future, as today's youth will be tomorrow's policy makers, judges and jury members, cases like Oscar Grant, Trayvon Martin and Jordan Davis might receive a more nuanced treatment and sympathetic reaction, and particularly the policies that enable these incidents will face critical engagement or even flat out rejection.

***

Usame Tunagur works as a video producer at Everest Production whose mission is to create programming promoting diversity and multicultural celebration. His short films have received numerous awards and screened globally at various film festivals. He is also a recipient of the 2010 National Association for Multi-Ethnicity in Communications Award for the TV show, World in America.

Published on March 03, 2014 20:20

March 2, 2014

The Space Age, Race and a Quiet Revolution by Dr. Mae Jemison

The Space Age, Race and a Quiet Revolution

by Dr. Mae Jemison | HuffPost Black Voices

The Space Age, Race and a Quiet Revolution

by Dr. Mae Jemison | HuffPost Black VoicesIn 1992, the Space Shuttle Endeavour made world history. I was on that flight, it was noted in the news: the first woman of color in space. When the Endeavour left the earth, the face of the space exploration changed.

When I returned to Earth, I was interviewed about my flight. "It is important, yes for young black girls to see me aboard exploring space. But it is just as critical that older white men who make so many decisions about engineering scholarships see me and understand the talent and potential of those girls," I said.

Growing up in the 60's, I avidly followed the Apollo missions and our journeys to the moon. I assumed I would travel to Mars to work as a scientist. My childhood was also right in the middle of the modern-day Civil Rights movement, and my parents made sure my brother, sister and I knew African American achievement was not new, nor did the push for full rights start or end with Martin Luther King Jr. There were others who changed the world. In fact, the praiseworthy term "the real McCoy" was coined in the 1800's because they wanted parts by inventor Elijah McCoy, a black man.

Former slave and suffragette Sojourner Truth declared, "If women want any more rights, why don't they just take them and not be talking about them." The early 1900's saw black people like Dr. Daniel Hale Williams perform the world's first successful open-heart surgery and Matthew Henson reach the North Pole with Admiral Peary. (So of course, my thirst for science and adventure fit right in.)

So, the little girl I had been was on my mind that day in 1992 when we launched. But alongside me, in the historical background, were others – the African-American engineers, rocket scientists, physicists, administrators, technicians and life scientists who helped build the space program of which I was part. They have been hidden. In the early years of NASA you could have counted the black professionals on your fingers. NASA engineer Morgan Watson is one of them. In the early 1960's in Alabama he and seven others broke the color barrier at NASA.

The stories of people like Watson are like so much of the African-American history, often marginalized and then forgotten. We think we know the story of civil rights and equal opportunity -- Martin Luther King, Fannie Lou Hamer, the Montgomery Bus Boycott, but there is also a powerful link with the Space Program.

Consider NASA's role in southern desegregation. In the early days, NASA's main centers were in the heart of what had been the old Confederacy. Huntsville, Alabama -- right next door to Decatur, where I was born – Houston , and Cape Canaveral, Florida. For the fewer than 50 African-Americans who came to those segregated communities to work at NASA, that new society started off just like the old one they knew, because local customs overrode Federal law which made discrimination illegal. Yet, overt segregation could not continue in facilities and companies that wanted federal contracts. And some of the most lucrative and prestigious contracts were with NASA!

Eventually the new frontier pushed us away from segregation. "The Space-Age" was part of building a new society as literally as we were aiming for the moon.

The promise and openness of space exploration and the determination of my talented African American colleagues at NASA is a legacy I can't ignore. And has profoundly influenced a big new challenge I am leading, 100 Year Starship, that seeks to make the capabilities for human travel to other stars a reality within the next century. Sound impossible to you? If the experiences of African Americans in the Space Program show us anything, it is this: big changes and explosive innovations come from tackling a really hard problem, stretching the limits of what you know, working with people in new, unexpected ways. It is my dream that in aiming for the distant stars, striving for the seemingly insurmountable, as we begin the first of many steps of this inclusive, audacious journey, we will transform life for the better on Earth all along the way.

***

Dr. Mae Jemison is the leader of the 100 Year Starship project. Learn more about the effect NASA'S space program had on the segregated south in the Soundprint program Race and the Space Race here.

Published on March 02, 2014 18:48

'Mad Black Men': Yes, There Were Black People In '60s Advertising

Published on March 02, 2014 13:55

Ben Horowitz & Steve Stoute on the Nexus of Tech & Culture

MrMagazineChanneL

MrMagazineChanneL

Ben Horowitz Co-founder and General Partner at Andreessen Horowitz & Steve Stoute, CEO of Translation Advertising discuss how technology innovation is transforming culture.

Published on March 02, 2014 09:02

February 28, 2014

Left of Black S4:E21: Does ‘Negro’ Cinema Matter in the Age of Global Blackness?

Left of Black S4:E21: Does ‘Negro’ Cinema Matter in the Age of Global Blackness?

Left of Black S4:E21: Does ‘Negro’ Cinema Matter in the Age of Global Blackness?

Left of Black host and Duke University Professor Mark Anthony Neal is joined via Skype by Professor Stephane Dunn, Director of the Cinema, Television, & Emerging Media Studies Program at Morehouse College and Esther Iverem, Founder and Managing Editor of SeeingBlack.com. Dunn and Iverem discuss the current state of Black film.Left of Black is a weekly Webcast hosted by Mark Anthony Neal and produced in collaboration with the John Hope Franklin Center at Duke University.

***

Episodes of Left of Black are also available for free download in @ iTunes U

***

Follow Left of Black on Twitter: @LeftofBlackFollow Mark Anthony Neal on Twitter: @NewBlackMan

Follow Esther Iverem on Twitter: @SeeingBlack

Published on February 28, 2014 12:15

"The Politics of Philanthropy": Imani Perry and Jelani Cobb on the President's "My Brother's Keeper" Initiative

All In with Chris Hayes

All In with Chris Hayes

Chris Hayes talks to his panel, including Imani Perry and Jelani Cobb, about the difference between policy and philanthropy.

Published on February 28, 2014 06:24

February 27, 2014

From 'Radical' To 'Revolutionary': dream hampton Remembers Chokwe Lumumba

Published on February 27, 2014 16:14

Joe Morton on 'Rowan Pope" and His Own Dad

Published on February 27, 2014 15:09

The Hip-Hop Fellow Outtakes: Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. speaks on 9th Wonder

Price Films

Price Films

The Hip-Hop Fellow is a feature length documentary following Grammy Award winning producer 9th Wonder's tenure at Harvard University.Interviewees include Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Kendrick Lamar, Young Guru, Dr. Mark Anthony Neal, Phonte, Dr. Marcyliena Morgan, Ali Shaheed Muhammad, Ab-Soul, Rapper Big Pooh & DJ Premier.

Published on February 27, 2014 04:18

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.