Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 819

June 5, 2014

(Not) Growing Up With Mariah by EmilyJ. Lordi

(Not) Growing Up With Mariah

by Emily J. Lordi | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

(Not) Growing Up With Mariah

by Emily J. Lordi | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)Mariah Carey’s new album has got me thinking about nostalgia, since I was once her biggest fan. I was 11 when she arrived in 1990 to send R&B pyrotechnics across the pop color line in five-plus cry-tinged octaves. I loved her.

I loved Whitney Houston first. But Whitney was my parents’ singer, groomed for the adult market from the start. With her slicked-back hair and string of pearls, 21-year-old Whitney looked like a tropical goddess on the cover of her 1985 debut, and was already singing opulent ballads like “The Greatest Love of All.” Whitney’s regal entrance reminded us that she, like Aretha Franklin, was a child of gospel royalty. Mariah, on the other hand, was more akin to Etta James—a mixed-race child of the working class whose ascendance was figured as Cinderella tale rather than birthright.

While Whitney’s day-glo “How Will I Know” video showed she could party with the MTV teens, that video also defines her as queen of the 80s. Mariah, who could seem like Whitney’s scrappy younger sister, was a 90s artist all the way—from her brooding songs to her unstudied beauty, from her claim to mixed-race identity in the early years of that term’s availability to her groundbreaking union of pop virtuosity and hip hop swag.

Her 1995 collaboration with Ol’ Dirty Bastard on “Fantasy” marked a pivotal alliance between rap and multiplatinum pop. While less controversial than Whitney’s marriage to “bad boy” Bobby Brown, “Fantasy” did entail fights with Mariah’s label and then-husband Tommy Mottola. But the song shrewdly anticipated the re-segregation of the Billboard charts, as black pop merged with hip hop and R&B while white alternative-rock crowd-surfed its way across the suburbs.

I lost track of Mariah around this time. Or rather, I averted my eyes from the girly rainbows and glitter that marked her second wave. If she had once seemed to affirm my own Italian-American looks, her hair now grew straighter and lighter and she seemed unable to cover up or to pleasurably inhabit her busty new body. The transformation and bravado was embarrassing. As Margo Jefferson notes of Michael Jackson’s eventually alien face, “He was not supposed to show this kind of need.”

Fast-forward to last month, when Carey released her oddly titled but critically acclaimed sonic scrapbook of an album, Me. I Am Mariah… The Elusive Chanteuse. She has called this her favorite album. It’s not mine. At 17 tracks it’s about 20% too long, and nothing on it approaches “golden age” songs like “Vision of Love,” “So Blessed,” and “One Sweet Day.” But that’s also the point. The album refuses nostalgia and tells a bigger story about how the 90s superstar diva—an artist who can seem like the last one standing in the spotlight glare—has tried to move on and grow up.

This might seem like an odd claim to make about a 44-year-old woman who dresses like a princess and shuts down Disneyland to renew her wedding vows with Nick Cannon. But in the wake of Whitney and Michael, Mariah’s insistently un-tragic if shallow persona also seems like a mode of survival. She tries hard not to take herself too seriously, and in so doing creates her own brand of hip-hop camp.

She has also sustained her formidable craft. As Jody Rosen has observed, the point of Carey’s music is less to express heartfelt emotion than to demonstrate “technical prowess.” For this reason her stage gestures are only convincing when she uses them to aid her own singing; she has never been good at acting out lyrics because her virtuosity is the drama.

The first track on the new album, “Cry,” is accordingly about losing love and about reacquainting us with Carey’s vocal skills, as the title’s compression of her name (“Carey” without the vowels) suggests. The heavy-handed piano accompaniment recalls classic ballads like “Vanishing,” while Carey’s wordy gospel interpolations evoke her roots and routes since then.

From here we get a choppy dance track, “Faded”; the lead single, “Beautiful,” which mixes illicit lyrics with a “middle of the night” run from “Girls Just Wanna Have Fun”; a club-oriented diss song “Thirsty”; a cover of George Michael’s “One More Try”; and a “cut him loose, girl” advice song with Mary J. Blige. “Supernatural” features Carey’s cooing twins and, like Beyonce’s “Blue,” revives but also privatizes soul music’s investment in (black) children, from “Young, Gifted and Black” to “Isn’t She Lovely.” Carey’s version of Reverend James Cleveland’s “I Don’t Feel No Ways Tired” evokes the soul era in a different way. Framed with samples of Cleveland’s sermonizing, the tribute weaves Carey back into the fabric of into Aretha Franklin’s 1972 Amazing Grace album, while establishing her place in contemporary gospel and overreaching with “updating” scratch effects.

To those stuck on early Mariah this eclecticism can sound like a bundle of affectations in the midst of which Carey sometimes graciously agrees to imitate her old self. But “Dedicated,” a rich collaboration with Nas, takes this problem in stride. In this song Carey makes space for others’ nostalgia without sharing it.

She begins by calling out Steve Stoute’s nostalgia for golden-age hip hop, which he admits and she proceeds to humor. She croons about singing “that good old-school shit to ya,” without voicing the good shit itself: the vintage loop from Inspectah Deck—“rap styles vary, and carry like Mariah”—does that for her. Long-time collaborator Jermaine Dupri fondly recalls how surprised he was to hear “Fantasy” and realize that Carey was “damn near a member of the Wu Tang clan!” This track re-genders nostalgia as male by figuring men as the ones stuck in a past that Carey moves on from. It seems the only one not nostalgic for 90s Mariah is Mariah herself.

She might be nostalgic for 1970s Mariah, though. In the final speaking track she explains the album’s title and the child’s drawing on its back cover. Titled “Me. I Am Mariah,” the drawing is “a personal treasure: my first and only self-portrait.” She felt now was the time to finally share it with “those of you who actually care and have been here for me through it all.” While this indulgence appears to signal nostalgia if not regression, Carey’s terrible line reading—which wholly belies her skills as an actress—also reveals the big reveal to be an act.

Carey’s candid artifice aligns her with Andy Warhol, whom she cites in the disco track “Meteorite.” But it specifically serves to eschew questions of authenticity that have dogged her career. These concerns were couched in racial as well as vocal terms, as when post-Milli Vanilli skeptics wondered if she was merely a “studio singer” who couldn’t cut it live. If her initial response was to prove that she was the real deal—her “Unplugged” set was meant to softly kill the skeptics—then her current tack is to make herself all “elusive chanteuse.”

This strategy not only helps Carey elude her critics but also frees her from the past and allows her to make new favorite albums. This is the story of Me. I Am Mariah, the working title of which was The Art of Letting Go. Still, as she sings in the superb last track, Letting go ain’t easy, oh it’s just exceedingly hurtful, ‘cause somebody you used to know is flinging your world around, and they watch as you’re falling down. The song’s beautiful use of modifiers, from “exceedingly” to Carey’s deep melismatic “falling downnnnn,” accents not what you do but how you do it. So it’s fitting that Carey sings about letting go by moving on, shifting into a chord progression that resembles the refrain of Jason Mraz’s recent hit “I’m Yours.”

“I’m Yours” is not a good song, but Carey’s citation of it reminds us that appropriation works across both sides of a “blurred line,” and that she has been listening to new music even if we haven’t been listening to her. Such adaptation makes it possible to believe our best days are ahead of us, even as we grow up and learn how much work it takes to make that true.

***

Emily J. Lordi is an assistant professor of English at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and the author of Black Resonance: Iconic Women Singers andAfrican American Literature (Rutgers, 2013). Her music essays have appeared on New Black Man, The Feminist Wire, and The Root. She is writing a book on the album Donny Hathaway Live (Bloomsbury 33⅓ series) and a musical-literary history of

Published on June 05, 2014 20:11

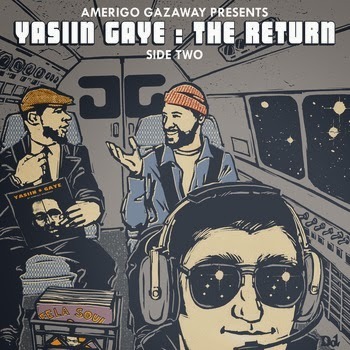

Yasiin Gaye: The Return (Side Two) -- Marvin Gaye Meets Yasiin Bey

AmerigoMusic Shifting focus for the second installment of "Yasiin Gaye", Amerigo aimed to highlight the often overlooked accomplishments of Marvin Gaye's role as the producer."I wanted to build this side from more of Marvin's original production work. He was doing a lot of what we do now, in terms of looping and pulling samples from other pre-recorded sessions decades before hip-hop made it common practice to do so. This also gave me the room to feature other artist [Chuck Berry, The Temptations, Talib, etc.] and re-present those classic Mos [Def] versus in a new context."

Published on June 05, 2014 14:16

AfroPoP Web Shorts: 'Passage' (A film by Kareem Mortimer)

NBPC

NBPCA twenty-year-old Haitian woman, Sandrine and her thirteen-year-old brother Etienne, are being transported from Haiti to the Bahamas in the hold of a dilapidated wooden vessel, filled with several other immigrants in search of a better life.

Published on June 05, 2014 12:31

June 4, 2014

How Art Can Change Society: Curator Sarah Lewis

Big Think

Big Think

Sarah Lewis describes how photography and music are often the catalyst for radical societal change. Lewis is an curator and historian based in New York. She is the author of The Rise: Creativity, the Gift of Failure, and the Search for Mastery .

Published on June 04, 2014 14:43

7 Marvin Gaye Songs You Should Know—#BMM2014

7 Marvin Gaye Songs You Should Know—#BMM2014

by Mark Anthony Neal |NewBlackMan (in Exile)

7 Marvin Gaye Songs You Should Know—#BMM2014

by Mark Anthony Neal |NewBlackMan (in Exile)“You’re the Man” (1972)

Recorded in between the What’s Going On studio sessions and those that produced Let’s Get It On, this was Gaye’s most explicit exploration of Black electoral politics. With the 1972 Presidential election and the Black Political Convention in Gary, Indiana as the backdrop—the gendered address of the song ignoring the candidacy of Shirley Chisholm—the song was meant as lead single for a second protest album from Gaye.

“If I Should Die Tonight” – Let’s Get it On (1973)

When Gaye began recording Let’s Get It On, it was intended as a thematic follow-up to What’s Going On. The former, instead, became Gaye’s legendary exploration of carnal desire. “If I Should Die Tonight” is the third track in the nearly perfect side one suite—and despite its obvious romantic overtones, the song takes on greater meaning in the midst of the losses within the Black Liberation Movement.

"A Funky Space Reincarnation" – Here, My Dear (1978)

Years before Mark Dery would coin the term, Gaye offered his view of Afrofuturism imagining a century forward in the future where “music won’t have no race.” Drawing no doubt on the popularity of Star Wars and the commercial success of P-Funk’s pro-Funk Disco, Gaye reboots the marriage and divorce that Here, My Dear documents a hundred years in the future (“2073…2084…2093”).

“Sanctified Lady” – Dream of Lifetime (1985)

“Sanctified Pussy”—as Gaye originally intended the song’s title—was the lead single from Dream of a Lifetime, the first posthumous release from Gaye in 1985. The song indexes Gaye's life long struggles with sexual and spiritual desire.

“I Wish I Didn’t Love You So” – Vulnerable (1997)

Gaye always imagined himself as a balladeer in the vein of Nat King Cole and Frank Sinatra, whose In the Wee Small Hours(1955) was particular inspiration. In the mid-1960s Gaye contracted producer and arranger Bobby Scott to work on a series of songs that Gaye tinkered with for over a decade, eventually recording versions that featured his signature vocal layering. The songs, including “I Wish I Didn’t Love You So,” appeared initially on Romantically Yours (1985), The Marvin Gaye Collection (1990) and finally, Vulnerable, which was released in 1997. The latter recording may be the best distillation of Gaye’s art.

“His Eye is on the Sparrow” – In Loving Memory (1968)

The defining tension in Gaye’s art—the desire for flesh versus the desire for spiritual salvation, often recast as salvation in the pursuit of the flesh—was a product of Gaye’s deeply religious upbringing and his stern Pentecostal preacher of a father (who, of course, killed Gaye in an act of self-defense). Gaye’s version of “His Eye is On the Sparrow” appeared on a 1968 tribute recording for Motown co-founder Loucye S. Gordy Wakefield.

“Baby I’m for Real” (1970/1972)

“Baby I’m for Real” was a breakout hit for The Originals, a group that Gaye worked with while preparing the What’s Going Onsessions. The work with the group allowed Gaye to explore his Doo-Wop roots and work out the vocal harmonies that would be featured on What’s Going Onand more explicitly on Let’s Get It On. “Baby I’m for Real” remains one of Gaye’s most stellar compositions as witnessed by versions by the Originals and the great Esther Phillips.

Published on June 04, 2014 08:57

Film Adaptation of Richard Wright's 'Big Black Good Man' (dir. Usame Tunagur, 2009)

Tamil Turk Films

Tamil Turk FilmsBig Black Good Man – 2009 (Usame Tunagur, Director/Writer/Editor) password: richardwright

Adapted from Richard Wright's short story (1958), Big Black Good Man, tells the story of Olaf, an old, white receptionist who is challenged to face his deepest anxieties when a young, black sailor checks in to his hotel.

Published on June 04, 2014 06:15

June 2, 2014

Sexual Violence, Shame and Black Male Allies

Sexual Violence, Shame and Black Male Allies

by Jas Riley

Sexual Violence, Shame and Black Male Allies

by Jas RileyAs a bright-eyed, eager, and naïve 21 year old, I donned my uniform with a clear awareness that my purpose for joining the service was for upward mobility. I did not anticipate leaving the post during break to discover I was pregnant. Troy drove me to the store to buy a pregnancy test and held my hand as we anxiously waited for the results. He held me as I cried and didn’t ask me how it happened. Mel sat with me while I talked to the guy who was responsible and listened while observing my response as we heard the guy on the other line say, “I knew you were pregnant; I was waiting on you to get back to me.”

He proceeded to tell me that he had to create a legacy. As I cringed in agony, Mel held me and cried with me, never asking why I had had sex with that guy. I wanted to scream that I pushed him off when he took the condom off, but I did not. Anthony drove me to the abortion clinic, waited with me, and cared for me practically hand and foot for a month while I recovered. They never told my secret because they understood the shame that I was and still am coming to terms with.

The shame I felt for trusting someone who could behave in such a way, the shame of promiscuity so often associated with Black women’s pregnancy, He did not look like a terrorist and he certainly did not consider himself one, but his actions—his purposeful blurring of the lines, his calm demeanor when he spoke to me, his complete disregard for my person nurtured in his misogynist tone which suggested that I should somehow be grateful that he wanted me enough to make me the mother of his seed— terrified me and still affects me.

Sexual violence and its perpetrators are often unassuming. The situations that yield such experiences are often so bound up in extended intimate relationships and a culture of sexual over-determination that the ability to recognize them as violations, or the desire of the victim to do so, is difficult to access. This is to say that the discussion on this touchy subject can never be directed to only those men “who would never have sex with a woman against her will and never want to be caught up in stupid situations that can be easily avoided” (Watkins).

While I am just beginning the healing process six years later, this incident forced me to recognize the ways Troy, Mel, and Anthony (two heterosexual and one queer black man) showed up for me. They did not judge me or pose thoughtless questions that would position me as essentially responsible or reckless, but, somehow, my twenty-one year old self—the one who had lost her virginity at twenty and only had one other sex partner beyond this guy—knew to be afraid to speak, to be ashamed of my actions, to blame myself, and to keep it a secret. These men showed up for me when I could not possibly show up for myself. The love demonstrated in their actions was radical!

For some of us, conversations about sexual violence do not move beyond such a limiting format (talk), so the extended imperative is to have discussions to entice debate. These conversations often turn into a show of muscle to flex a narrative of Black or African American exceptionalism. And for many us the realities of sexual violence significantly impact our lives even though our stories are considered simply unremarkable. So words and the passion animating an underlying desire to one-up a seeming enemy rather than sincerely understand the pain associated with various intricate forms of sexual violence and their impact in a culture that still does not know me—a young, Black woman—can be suffocating.

The sting of abortion from an act our culture deems inherent to my deviant nature demands that I question my ability to engage in pleasure, as well as my belief in the possibility of my own victimhood. What I need you to do is recognize how your words have violated women, to take off the blinders of exceptionalism, and see me. Don’t feel sorry for me, but move for me! Recognize the history of non-subjectivity your senseless questions and trivialization of the likes of me as freaks invokes and how it registers a personal injury. Recognize how your inherent distrust or the ill-informed misbelief that your plight as black man is somehow more significant enacts a similar historical violence that informs my present being. Be careful with your questions, throw down your defenses, and act in community WITH me.

“Consent to not be a single being” (Glissant) and act out of love and compassion rather than blame. We are in this together, so let’s not buy into an allusion of boundaries that will allow us to maintain such a harmful power dynamic that continuously fractures and intimidates any notion of a Black collective. The impact of sexual violence and its intimate nature cannot and should not be reduced to simply a “healthy debate” (Watkins).

I am hurt, but I don’t want to hurt you. I want you to “Get in [my shoes]” (Watkins). I need you to understand what informed my fear and I need you to believe me and help me believe me by not referring to the likes of me, whose similar situations may or may not be informing their sexual decisions as a “wolf in freaks clothing” and assuming that you know them. Begin to learn to love me fearlessly like I love you. My peace of mind and the confidence that love as a verb from you encompasses does not threaten your manhood. And if you think it does, then you prove my point we need to do more than talk. Show up for me!

***

Jas Riley is a southern born Black feminist poet who wondered her way into the world of formal criticism somehow. She is currently a student in the English PhD program at the University of California, Riverside where she studies African American Literature, Black Feminism, and Queer of Color Critique.

Published on June 02, 2014 15:03

When There Isn't a Case for Debate: Black Men Listening to Our Sisters

Carrie Mae Weems (The Kitchen Table Series)

When There Isn't a Case for Debate: Black Men Listening to Our Sisters

(organized by Brothers Writing to Live)

Carrie Mae Weems (The Kitchen Table Series)

When There Isn't a Case for Debate: Black Men Listening to Our Sisters

(organized by Brothers Writing to Live)Brothers Writing to Live is a collective formed across identities, geographical boundaries and generations to create space for black men to work through the question of what a progressive black masculinity looks like. We come together through the understanding that there is power and transformation in collective struggle. It is imperative that we push one another, with trust and love, to think critically about the ways we move in a world created by toxic visions of blackness and manhood.

It is with that as our mission that we have recently engaged in a public conversation around the issue of sexual violence, one sparked by the dissemination of retrograde ideas surrounding black womanhood through the blogosphere. We reject these ideas on the basis that they help promote rape culture and absolve black men of their responsibility to confront the destructive forces of patriarchy, misogyny, and sexism that continue to afflict the lives of black women. It is particularly egregious given that black women have been at the forefront of movements to end racist oppression of black men. It is cause for shame that we have not shown up in a meaningful way for them.

Brothers Writing to Live seeks to model a new path forward, where black men are no longer silent on the issues which face black women, particularly those that implicate black men. We have talked. We have written. But talking and writing are not enough. The most radical thing we can do is listen. We must learn to actively and intently listen when black women tell us the stories of their lives and what we as black men need to do in order to support them. We must learn to step back from our privilege and be led by the sisters already doing the work. We can not presume to know all there is to know about patriarchy, misogyny, and sexism ravaging our black communities. We must be willing to hear the truth about our complicity in these system of oppression and hatred, and then take adequate steps toward reconciliation and healing.

It is with this in mind that we turn to our sisters, whose brilliance is unmatched and whose dedication to building strong communities inspires us all to move forward with the same graciousness, respect, and love that they have shown us throughout history.

Here, we listen. We encourage you to listen, too.

Mari Morales-Williams:

I’m the education director of a community center in a tough neighborhood in North Philadelphia. One day, I was speaking with a 9 year Puerto Rican boy in my office about his phone. When I asked him who he texted, two other young men in their 20’s joked, “He texts his girlfriend.” The boy laughed and agreed. When I asked him why did he like his girlfriend, he said that she had a big butt. I looked at him squarely and probed, “Is your girlfriend a body part or a human being?” He laughed and said, “A body part.” The older youth joined in his banter.

That is what misogyny sounds like on a 9 year old boy. And as long as men continue to think that that is funny or not that big of a deal, then they will have a hard time seeing how that kind of thinking has unhealthy effects on how young boys and men build genuine relationships with girls and women. That kind of thinking keeps boys and men from seeing how they become violent with women in small and profound ways. I’m not speaking of brutal acts of violence that are privileged in media. That is a naïve and basic way to think about how sexual violence occurs in reality. I mean the everyday violence that is seen as “not that serious”: harassing a girl in the street because of what she is wearing, bullying a girl in school because she doesn’t like you, only being courteous to feminine presenting women or women you think are pretty, only engaging with women to have your needs fulfilled, and the list goes on. Men can end sexual violence by broadening their minds about what that violence looks like and being honest about how they might engage in that. They can stop it by letting their younger brothers know that such violence is far from something to joke about, but a sore wound that we all need healing from.

Lori Adelman:

"We are of the same blood, you and I." -Rudyard Kipling

Vengeful. "That woman". Leg-opener. Diseased. "Stripper/jump off/random woman." Child-support thief. Life-ruiner. "FLAT-OUT-CRAZY." Temptress. Deceitful. "A wolf in freaks clothing." Punitive. Greedy.

These are just a few of the characterizations of black women perpetuated in an effort to make the case for black men to "be careful about their sexual choices" and presumably avoid fates such as unwanted fatherhood, STIs, or unjust detention.

I wish I were more surprised. I wish I could feign outrage or even ignorance. But the truth is, I've become accustomed to this line of thinking, one in which uplifting blacks is a zero-sum game requiring sacrifice in the name of solidarity above all -- which just happens to fall neatly across gender lines. In this line of thinking, rather than tackling systemic injustices by fighting said systems and the correlating powers-at-be, we can simply demonize and deride black women, and particularly their sexuality, to solve a problem like mass incarceration.

I understand the pain goes deep, and black men are looking for solutions to a problem they didn't invent, that shouldn't exist. But our pain goes deep, too. The rates of sexual violence -- including intimate partner violence and sexual assault -- against black women are alarming. Hateful stereotypes and mischaracterizations compound this unprecedented epidemic in ways both concrete and immeasurable.

This is hardly a battle of the sexes; for community solutions to a wide range of issues, black men need look no further than the very "jump offs" and "wolves" they so joyously berates. Rather than trumped up stereotypes of mythical female demons, black women are community leaders; activists; organizers; advocates; journalists; and so much more. We are in the streets fighting against unfair drug laws and "stop & frisk" policies, and for reproductive health access in our communities. We may make for an easy scapegoat, but women of color are not the obstacle standing in the way of black men's emancipation. We must be each other's saviors, not demons. We are of the same blood.

Je-Shawna Wholley:

There is a way to encourage men to make healthy and informed decisions about their sexual partners without painting this picture of women being gold-diggers, conniving, and armed with an agenda of entrapment. What is to be gained from this narrative? Where is the self-accountability? At the end of the day, the key to saving Black men should never be the demise of Black women. We are not your enemy.

Moreover, we often speak of rape with a lightness that completely dismisses the trans-historic and everlasting trauma that is a result of rape and rape culture. As a Black woman who is also a survivor of sexual assault conversations centered on rape are honestly triggering for me. I vividly remember sitting in the court room on the same pew as my assailant’s family. I remember feeling shamed when his mother looked at me and then shouted out to her son “it’s going to be okay baby,” as if to let me know that she “knew” her son was innocent. I remember her glares. I remember the sadness I felt as I looked at his toddler son. I was putting another Black father in jail. I was responsible for another Black boy growing up without his father. But these internalized pressures are far from the truth. I was not responsible for any of that. No matter how hard it must be for that mother to realize that her son sexually assaulted me, it is the truth. I did not “put” him in jail; his actions and the punitive system that we live by are responsible for that.

Instead of centering the bodies and experiences of Black women in a conversation amongst men about “how to not be accused of rape” I would like to see men having a healthy dialog about consent. What does it mean to gain consent from your partner? How do you start that conversation? What is the difference between “yes” and “not no?” Is there a difference between the two? What are healthy sexual boundaries? Who determines these sexual boundaries in our society, men or women? How do we honor the trans-historic realities as it pertains to Black bodies (of all genders)?

Mariame Kaba:

Feminist organizers responding to the murders of black women in Boston in 1979 marched in the streets in protest carrying a banner with a line from a poem by civil rights organizer Barbara Deming which read: “WE CANNOT LIVE WITHOUT OUR LIVES.” In 2014, the assaults against Black women are unrelenting. We continue to be disproportionately beaten, stalked, raped, imprisoned, disappeared, and murdered. We are fighting for our lives. We need solidarity rather than vitriol and violence from black men.

In his seminal 1970 essay about rape, Kalamu ya Salaam wrote: “The rape of African-American women is not seen as a major problem precisely because the victim is both Black and female in a racist and sexist society.” We desperately need black men to see anti gender-based violence as a primary site of their activism and organizing. I can only ask ‘what’s taking so long?’ We desperately need each other if we are to live fully and ultimately be free. Black women cannot live without our lives.

Brittany Carter:

The idea that being falsely accused of rape is as harmful as the actual rape of a black woman's body is rather mind-blowing. The same line of thinking informs the popular claim that being called a racist is somehow as harmful as enduring the actual violence of white supremacy. This is the ingenuity of dehumanization - attempting to level the playing field between the oppressor and the oppressed so that the two become indistinguishable and justice itself becomes elusive. If the conversation is, in fact, about justice (and it should be), then surely there is a way to lay out the harms of false accusations of rape and their contributions to the epidemic of mass incarceration without doing so at the expense of our sisters. Historically, subjugating black women in the service of black men's liberation is a strategy that has not served the black freedom struggle well.

Charlene Carruthers:

We too, are human and deserving of safety and agency. Black women don't need protection -- we need recognition, respect, love and the forging of transformative spaces in partnership with Black men.

Sarah Haley:

Recently, some have attempted to shed light on a taboo and allegedly serious (but undocumented) problem of black women’s complicity in black male incarceration, claiming this as a radical act of antiracism. Some might believe that trafficking in powerful and wholly American stereotypes of black female sexual treachery is an effective strategy to make the academy more relevant to black communal interests. By this logic exposing a hidden pattern of women’s sexual revenge (erroneous rape allegations) that purportedly leads to black male incarceration is a public service. This strategy is…regrettable. Critics of this approach have been accused of espousing Democratic liberalism, which is ironic because it is the notion that black women are to blame for black men’s carceral downfall that constitutes the mainstay of mainstream bipartisan law and order politics; such stereotypes of black female moral and sexual pathology contribute to the criminalization of black women to be sure, subjecting them in disproportionate numbers to the terror of incarceration each and every day. But they also fortify assumptions about the thorough and unredeemable inferiority and criminality of black communities writ large. For such morally bereft and lascivious black women are believed to inculcate and socialize (if not biologically propagate) moral deviance, endowing their daughters and sons with such depraved and criminal characteristics and reproducing a culture (tangle) of pathology. This condemnation of blackness that scholars have so eloquently exposed ensnares both black women and men in extraordinarily violent regimes of exclusion and captivity. It is an inadvisable approach to refute presumptions of black male guilt by imposing such presumptions upon black women. Of course there are other ways of thinking about gender, violence, and imprisonment. Black women and men in and beyond the academy have advocated prison abolition, one of the most radical and expansive critiques of white supremacy and the prison industrial complex. This abolitionist theorizing and organizing emerged from a deep and thorough recognition of the magnitude of harm that imprisonment wreaks upon poor, LGBT, Black, and Brown communities, women and men. It comes from the recognition that carceral terror relies upon late capitalist surpluses and stereotypes of black male threat as well as notions of black female deviance, black women’s perceived irrationality, unscrupulousness, and hypersexuality. Dismantling will prove far more effective than redeploying the ideological brick and mortar of mass incarceration.

Danielle Moodie-Mills:

Excusing rape by blaming black women for our "wild ways" is not only disturbing but an incredibly dangerous act. The number of men that have been wrongly accused of sexual assault pales in comparison to the number of women that are scarred both emotionally and physically by having their bodies violated against their will. We need to have honest conversations about rape and rape culture within the black community that don't pin men against women and vice versa. We need to create a culture of respect and compassion for black women, not degrade them as objects of sexual desire or perpetuate the idea that black women are just trying to "trap a man" and are mischievous and not to be trusted. Instead of enlightening the "brothers" using old tropes to that allow black men to escape responsibility from ending rape and rape culture. We need responsible policy and engagement not rhetoric.

Heidi Renee Lewis:

Just over a year ago, in March 2013, my colleagues and I published short video responses to Rick Ross' "U.O.E.N.O." lyrics in which he raps about giving a woman drugs and having sex with her without her knowledge. While we did receive a lot of support for speaking out against rape culture, we also received many heinous and violent threats. One viewer commented that the women in our videos should actually be raped. For these reasons and others, it was, and still is, important that our brothers, including Darnell L. Moore and Mark Anthony Neal of Brothers Writing to Live, participated in the videos. These Black men were able to stand strong beside (not in front of) Black women, because they know, as we all should, that 1 in 3 women will be raped in their lifetime and that most sexual assaults are committed by perpetrators of the same race as their victims. These Black men were able to stand strong beside (not in front of) Black women, because they know, as we all should, that most Black women victims of sexual assault remain silent due to the shame and violence they fear they will face if they speak out. Almost 40 years ago in "A Black Feminist Statement," the Combahee River Collective wrote, "We struggle together with Black men against racism, while we also struggle with Black men about sexism." The same year, Audre Lorde reminded us, during a panel at the MLA, "My silences had not protected me. Your silence will not protect you." How long will it take for us to learn that we must work together to fight a persistent and dominant rape culture that tells Black women that we aren't worth the love and loyalty that we need? How long will it take? How long?

Sikivu Hutchinson:

Every day I work with young Black women and girls who have been emotionally and mentally battered by the constant cultural propaganda that their sexuality is dirty, pathological and destructive. As “protectors” and “defenders” of Black masculinity, black girls are taught early on that unquestioned allegiance to Black boys and men should supersede their allegiance to themselves. They learn early on that there will be no “My Sister’s Keeper” initiatives to “save” them, nor national attention given to the epidemic rates of sexual assault, intimate partner violence, HIV/AIDS contraction and Black female criminalization that jeopardizes all Black lives, families, and communities. They are repeatedly shown in white supremacist corporate mass media, popular culture and the Black community that violence and systematized terrorism against Black women and girls is acceptable, normal and “just the way shit is”. Despite the long history of radical Black feminist resistance, violence against Black women and girls has never been regarded as an urgent civil or human rights issue in Black liberation struggles. Due to this history, it is imperative that more Black men and boys stand with Black women and girls against the structures of patriarchy, sexism, heterosexism, homophobia and transphobia which normalize and institutionalize violence against women of color. For starters, Black men and boys can begin having the difficult conversation about how toxic, naturalized images of hypersexual Black women and women of color shape their everyday practice, relationships, sexuality and gendered perceptions. They can actively support the intersectional activism of black cis, lesbian, bi and trans women around intimate partner violence, HIV/AIDS and STI education, sexual assault and criminalization. Instead of venerating the usual charismatic male civil rights heroes they can lift up the lives of lesser known figures in movement struggle like Ida B. Wells, Claudette Colvin and Recy Taylor; women whose forerunning activism linked Black women’s resistance to sexual assault and sexual harassment with civil rights struggle. Through the holocaust of slavery and racial apartheid, Black men have never been told by Black women that their dehumanization was normal, natural and “just the way shit is”. Yet, even when it was at their expense, Black women have always been expected to uncritically support Black men’s self-determination. This double standard endangers Black lives.

Syreeta McFadden:

I wonder what kind of naivete persists in this conversation among men in our community that would continue propagate a narrative of rampant mistrust of women that could ultimately lead to sexual misconduct, assault and rape. I wonder what's at stake for masculinity when we teach men not to rape. What is it about no that we fail to understand? How is possible that we do harm to people we claim to love? What kind of world do we believe must be protected to teach young men to embrace this ideology?

This argument is intellectually dishonest and reductive. One vague anecdote of a sexual assault case does not a rule make. While I'm not ignorant the legacy of false claims of rape by white women in a racist society, that boondoggle has now become a cloak and crutch for our community to engage in serious discussions about sexual assault and violence within our communities. The gospel of respectability mired in dated tropes of feminine and masculine identities have barred us, in many instances, from reckoning with the realities of sexual assault and misconduct and acts of violence against women on HBCUs.

We know better and we can do better to address it.

Aishah Shahidah Simmons:

FBI statistics state that less than 2% of reported rapes are false charges. Another way of looking at this is that 98% of reported rape charges are true. There are many more rapists who lie about raping women then there are women who lie about having been raped. Black men need to ask themselves why it’s so much easier to focus on the very small percentage of false accusations than it is to focus on focus on the pervasiveness of rape? I believe Black men have a non-negotiable responsibility to focus on addressing and ending rape in our communities.

In the last stanza of his riveting poem, “To Some Supposed Brothers,” the late, award-winning Black Gay Poet Essex Hemphill wrote,

But we so-called men,

we so-called brothers

wonder why it’s so hard

to love ‘our’ women

when we’re about loving them

the way america

loves us

As a community we have an acute collective awareness about the horrific impact of racism in our communities, especially as it relates to Black men and boys. Unfortunately, however, we tend to close our eyes and ears when it’s time to raise awareness and talk about the horrific impact of intra-racial rape, sexual assault and other forms of violence perpetuated against Black women in our communities. We spend so much time blaming women and girls for the violence that they experience at the hands of men and boys in ways in which we do not tolerate (without protesting) the blaming of Black men and boys for the violence that they experience at the hands of white supremacist state sanctioned violence.

We must remember that single-issue politics will never be our community’s salvation. If we do not address gender-based violence while we simultaneously address white supremacist violence, over half of our community will be vulnerable to all types of unspeakable violence, which will render our communities unsafe and not healthy.

Published on June 02, 2014 04:27

June 1, 2014

Filmmakers at Google: Amma Asante, Director of 'Belle'

Talks @ Google

Talks @ Google

Filmmakers at Google hosted director Amma Asante at the Googleplex for a talk to discuss her 2014 Fox Searchlight film, Belle. This film was inspired by an 18th century painting of Dido Elizabeth Belle and her role in shaping the end of slavery in England. Clennita Justice, Engineering Program Manager of Google Play, is the host.

Published on June 01, 2014 13:12

May 30, 2014

Jay Smooth: A Conversation with Pharoahe Monch

Jay Smooth

Jay Smooth

A few weeks ago one of my favorite artists, Pharoahe Monch, came by the radio show and we had a great convo about writing process, loving Octavia Butler and what his Little Hater sounds like.

Published on May 30, 2014 15:00

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.