Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 816

June 22, 2014

Blitz the Ambassador Chronicles Hip-Hop’s ‘Mobile Diaspora’ in Afropolitan Dreams

Ghanaian-American rapper Blitz Bazawule’s new album sonically maps the roots and routes of a new cosmopolitan Diaspora.

Blitz the Ambassador Chronicles Hip-Hop’s ‘Mobile Diaspora’ in Afropolitan Dreamsby Mark Anthony Neal | The Root.com

It’s telling that Samuel Bazawule—aka Blitz the Ambassador—was introduced to hip-hop as a child in Ghana via the music of Public Enemy.

While “Niggas in Paris” like Kanye West and Jay Z are most often recalled in fantasies and nightmares of hip-hop’s global expansion, rappers have been in the vanguard of a black cosmopolitan identity for almost 40 years. That’s part of the joke that opens Bazawule’s new release,Afropolitan Dreams, recalling his arrival in the United States and the incredulous response of an immigration officer to his stated profession: “rapper.”

And the title of Bazawule’s new recording is drawn from a term coined by writer Taiye Selasi in her 2005 essay, “Bye-Bye Barbar,” where she thinks aloud about a generation of African immigrants who weren’t simply cosmopolitan—citizens of the world—but Afropolitan, or “Africans of the world.”

Though the idea of Afropolitanism has been debated in some circles, Bazawule strays from those concerns, asserting that he was inspired to create Afropolitan Dreams by meeting peers in different disciplines. “What we had in common,” he says, “was that we were all immigrants.” A theme that finds initial grounding in the audio references to the New York City subway system on the opening track, “The Arrival,” produces its own cosmopolitan logic within the context of the city. Here Bazawule is in sync with how late political scientist Richard Iton, in his book In Search of the Black Fantastic, theorized the Diaspora as distinguishing between “roots” and “routes.”

Read Full Essay

Published on June 22, 2014 19:59

Long before Bowe Bergdahl, Beards Treated with Suspicion — and as a Health Risk

Public Radio International | PRI

Public Radio International | PRIEver since Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl was released in a prisoner swap with the Taliban, there's been a lot of discussion. Not just about the deal itself, but also about beards.

Published on June 22, 2014 15:17

¿Que pasó? Horace Silver Left Town: An Appreciation

¿Que pasó? Horace Left Town: An Appreciation

by Matthew Somoroff | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

¿Que pasó? Horace Left Town: An Appreciation

by Matthew Somoroff | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)Horace Silver’s death on June 18 brought well-deserved tributes from the press: the New York Times’ obituary noted that “[m]any of his tunes became staples of the jazz repertoire” and the Washington Post rightly called him “a primary developer in the 1950s and 1960s of the style of jazz known as hard bop.”

Silver grew up working-class (and black) in (overwhelmingly white) Norwalk, CT. In the late 1940s, he began performing professionally around Connecticut. By 1951, he’d moved to New York to continue his work as a musician. With drummer Art Blakey, Silver formed the Jazz Messengers during the early 1950s. This alliance yielded two of the most enduring and noteworthy jazz ensembles of the latter half of the twentieth century: Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers and the Horace Silver Quintet.

In playing a crucial role in the development of hard-bop, Silver also helped to establish the classic Blue Note Records sound of the 1950s and 1960s: small-ensemble recordings (typically quintets or sextets) with an emphasis on original compositions bearing a bluesy tinge. The musical directions that Silver and Blakey carved out during the early 50s laid the groundwork for recordings by Donald Byrd, Lou Donaldson, Jackie McLean, Lee Morgan, Stanley Turrentine, and others. Iconic Blue Note albums like Byrd’s A New Perspective , Morgan’s The Sidewinder , or Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers’ Moanin’ owe their respective sounds to Silver.

The shadow of Silver’s compositional style looms large over Herbie Hancock’s debut album, Takin’ Off . The many hard-bop tunes Wayne Shorter contributed to Blakey’s Jazz Messengers (and hence to the jazz repertory) are indebted to Silver’s innovations in jazz composition. The popular soul jazz recordings of the 1960s by the Cannonball Adderley Quintet and the Ramsey Lewis Trio are rooted in Silver tunes like “The Preacher” and “Señor Blues.”

Silver’s importance as a bandleader cannot be overlooked. Like those of his former bandmate Art Blakey, and Miles Davis, Silver’s bands provided invaluable exposure for up-and-coming talent in the jazz world. A partial list of notable musicians whom Silver mentored must include trumpeters Blue Mitchell, Woody Shaw, Randy Brecker, Tom Harrell, and Dave Douglas; saxophonists Hank Mobley, Joe Henderson, Bennie Maupin, and Michael Brecker, and Bob Berg; drummers Louis Hayes, Roy Brooks, Roger Humphries, and Billy Cobham.

By the mid-1960s, Silver had developed a rich inventory of melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic devices to produce new compositions. In other words, once he’d formed a personalized musical language, Silver began to repeat himself, recycling old materials in new tunes. Other composers who also used this approach to producing new music include Johann Sebastian Bach, Duke Ellington, Thelonious Monk, and Cole Porter. Like them, Silver’s inventory of musical devices was large enough to permit a multitude of new permutations.

What precisely were Silver’s contributions to jazz composition and style? One of his greatest achievements as a composer was synthetic. In various configurations, Silver mixed the harmonic complexity of bebop, melodic phrasing from the blues and gospel, and rhythmic feels from R&B and Latin music. He was capable of writing ornate melodic lines akin to Charlie Parker’s classic bebop tunes, but more often he wrote clipped, strong, riff-based melodies and wedded them to unexpected chord progressions.

Silver also pioneered different approaches to arrangement and ensemble texture within his chosen format of the two-horn/rhythm section quintet. His compositions rarely consisted merely of a melody over changes. Instead, he might create call-response phrases between himself and his horn players (e.g., “Filthy McNasty”), or use stop-time rhythmic figures to generate musical tension (e.g., “Break City”).

I asked my friend Aaron J. Johnson, a professional trombonist and music scholar who just earned his PhD from Columbia, for some thoughts on Horace Silver. He replied, “His music led the move to hard bop and hard bop supercharged the connections between jazz and the black community. Hard bop is the broad genre that kept jazz in inner city bars and clubs all over black America and kept jazz on black radio deep into the 1960s.” Johnson also had the following insight into Silver’s musical approach: “If you listen to the solos on ‘Cape Verdean Blues’ starting with Silver’s own on piano, they adhere to the form of alternating two-bar solo phrases with two-bar phrases of the band playing the groove. This is Silver's answer to organizing the combination of improvisation and composition, and how to get folks to solo on the tune, not on the changes (as Ornette Coleman later put it.)”

In 1970, Silver experienced a newfound interest in spiritualism and metaphysics. He began to compose and record music that expressed these convictions. The resulting trilogy of albums, titled The United States of Mind , was grudgingly released by Blue Note. After leaving Blue Note in 1980, he founded his own record label, Silveto, with the hope of releasing music that diverged from the quintet-based hard bop for which he’d become famous.

Silver’s spiritually-minded music never found much of an audience. His existing base of listeners wanted more of the Horace Silver who wrote and performed soulful instrumental jazz. The Silver of The United States of Mind and the Silveto recordings has been effectively written out of the dominant jazz history narrative.

During the late 1990s, Silver fell back into critical favor with two albums he recorded for the resurrected Impulse! label. His next recording, made for Verve in 1999, is titled Jazz…Has…a Sense of Humor . It could be read as a cheery observation or as Silver’s admonition to the jazz world.

Horace Silver’s final work turned out to be his 2006 autobiography, Let’s Get to the Nitty Gritty . It is written in a voice resembling his musical style: direct, unpretentious, by turns idealisticand sassy. Silver expresses gratitude at his musical gifts and successful career, but also gives voice to lingering frustrations over the incomprehension that has met his post-1970, spiritual music.

§

I’m almost ashamed to admit that for a while during my late teens and early twenties, I thought I was above Horace Silver. That came only after I’d had a love affair with his music. I remember first getting into Horace Silver during high school, when I was about 16. My father and I had become obsessed with Sonny Rollins’ 1957 recording of “Misterioso,” which featured both Thelonious Monk and Horace Silver on piano. Obviously, Rollins and Monk were both amazing on the track, but we were also turned on by the stark simplicity and deep groove of Silver’s solo. We dug deeply into Silver’s classic Blue Note albums Blowing the Blues Away, Horace-Scope, Six Pieces of Silver and Song for My Father. And we couldn’t get enough of the catchy riffs and the grooves.

But by the time I was 19 or 20, I had grown weary of those records. I was expanding my musical horizons and had become too hip for Horace. The hummable melodies, the clever shifts in rhythmic feel, the stylized blooziness all began to sound like Silver was constantly winking and grinning at the listener, like a party guest who substitutes an insufferable schtick of one-liners for actual conversation.

In hindsight, I think I’d gotten swept up in the lowest-common-denominator popular conception of Horace Silver, the thumbnail sketch found in jazz history books that reduces him (and the hard bop school) to a producer of finger-snapping, good-time music. Even though I had Silver recordings to refer to, I had not really listened to them for quite a while. I’d forgotten the wry dissonances in tunes like “Kindred Spirits,” or “Nutville.” It had not occurred to me that some of Silver’s greatest compositions were his ballads, such as “Melancholy Mood” and “Peace.”

It’s now hard for me to discern the source of my discomfort with some of Silver’s tunes. Is it more that I hear some of his “funky” compositions as full of mannerisms? Or is it more the cheeky humor of some of the titles of his compositions, their insipid wordplay and offensive connotations (e.g., “Juicy Lucy” from Finger Poppin’, “Ah! So” from The Tokyo Blues, or “Calcutta Cutie” from Song for My Father)? But Silver’s occasional penchant for facile exoticism was hardly unique among jazz musicians – just think of the caricatured “redface" intros to the versions of “Cherokee” by both Bud Powell and the Clifford Brown/Max Roach Quintet.

In preparing this remembrance, I’ve listened again, particularly to deeper cuts and to forgotten recordings like You Gotta Take a Little Love and The United States of Mind. I felt it was the least I could do to recognize someone who filled my imagination early in my musical life and whose music continues to provide nourishment and pleasure. I selected some favorites from Silver’s vast and accomplished catalogue of recordings:

“My One and Only Love” from The Stylings of Silver (1957)I choose this recording as an appreciation of both Silver’s arranging abilities and his elegant understatement as a ballad player. Silver makes the unexpected move of taking the lead and playing the song’s melody himself, assigning the horns sustained harmonies and stop-time background figures. The result is that, during the melody statements, Silver achieves the textural breadth of a much larger ensemble within the quintet format. Check out Silver’s solo for a great example of his pianism: a style essentially coming out of Bud Powell, but more pared down and with a heavier blues element.

“Lonely Woman” from Song for My Father(1964)This is one of my favorite examples of Silver’s pianism and definitely my favorite of his ballads. Listen to the protracted ending of the track: a poetic evocation of an exhausted and tedious loneliness. Incidentally, I’ve come to hear Pat Metheny’s choice to cover Silver’s “Lonely Woman” on his trio album Rejoicingas intensely symbolic. Charlie Haden and Billy Higgins, the rhythm section of the classic Ornette Coleman Quartet, accompany Metheny on Rejoicing, which features three Coleman tunes. Metheny forgoes Coleman’s canonical “Lonely Woman” for an Ornette Coleman tribute album in all but name, instead choosing the other “Lonely Woman.”

“Acid, Pot or Pills” from The United States of Mind, Phase II: Total Response (1971)The rhyme scheme of the lyrics might sound a bit square, but the groove is badass. This track comes from Silver’s United States of Mind project, three albums of original songs for which Silver also wrote the lyrics. These recordings feature Silver on the RMI electric piano (in his autobiography he states that he chose the less popular keyboard because he had tired of hearing everyone play the Fender Rhodes keyboard). The United States of Mind albums were critically and commercially unsuccessful, in large part because they fit neither the marketing categories of the music industry nor the expectations of the jazz press: the music had too much funk and soul to be jazz, but too much hard-bop to be soul or R&B; the lyrics were too plainly optimistic and spiritual for a jazz album (or perhaps for an album of the early 1970s). The albums were an eccentric mix of jazz, gospel, and late-60s hippie utopianism, and the jazz world didn’t want to hear this from Horace Silver. (See the Afterword to Silver’s autobiography for more on these albums.)

“Summer in Central Park” from In Pursuit of the 27th Man (1972)The hornless instrumentation (vibes, piano, bass, drums) used for this urbane jazz waltz is atypical for Silver. The harmonic style of the tune suggests that Silver had been absorbing some of the modal/post-bop experiments of younger composers like Chick Corea, Herbie Hancock, or Joe Henderson. And check out the fleet, hip lines Silver plays during his solo!

“Philley Millie” from Jazz … Has … a Sense of Humor (1999)On his final recording date, Silver the composer, pianist, and bandleader grooves as exuberantly as ever. This mid-tempo swinger is classic Silver: a melody simple enough to be hummed upon first hearing, but joined to a chord progression with enough kinks to keep things interesting. Silver’s solo almost resembles Count Basie or mid-50s Miles in its pithy concision. The shout choruses the horns play in alternation with Silver’s soloing are also a favorit* * *

Matthew Somoroff is a writer and independent scholar living in Durham, NC. He received his PhD in Music from Duke University.

Published on June 22, 2014 13:54

Joel Christian Gill: Strange Fruit, Volume I: Uncelebrated Narratives from Black History | Talks @ Google

Illustrator Joel Christian Gill talks about his new book Strange Fruit, Volume I: Uncelebrated Narratives from Black History, which tells the story of 9 "uncelebrated heroes" including Henry Box Brown, Alexander Crummel and Bass Reeves. At the Google offices in Cambridge, MA.

Published on June 22, 2014 09:31

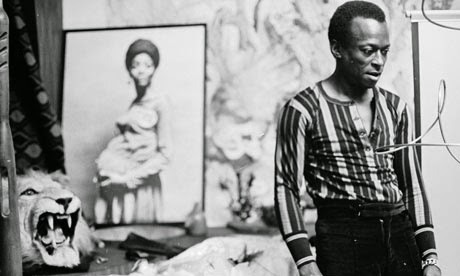

7 Miles Davis Songs for a Sunday Summer Brunch

7 Miles Davis Songs for a Sunday Summer Brunch Compiled by NewBlackMan (in Exile)

All Blues (Kind of Blue, 1960)

Milestones (Milestones, 1958)

Seven Steps to Heaven (Seven Steps to Heaven, 1963)

Human Nature (You’re Under Arrest, 1985)

Tutu (Tutu, 1986)

It’s About that Time (In a Silent Way, 1969)

Miles Runs the Voodoo Down (Bitches Brew, 1970)

Published on June 22, 2014 06:24

June 21, 2014

'Orange is the New Black' on the Real (Corporate) Criminals

Published on June 21, 2014 07:23

June 20, 2014

TED Talk: Jamila Lyiscott on being 'Articulate' and a 'Tri-Tongued Orator'

TED

TED

Jamila Lyiscott is a “tri-tongued orator;” in her powerful spoken-word essay “Broken English,” she celebrates — and challenges — the three distinct flavors of English she speaks with her friends, in the classroom and with her parents. As she explores the complicated history and present-day identity that each language represents, she unpacks what it means to be “articulate.”

Jamila Lyiscott is currently an advanced doctoral candidate and adjunct professor at Columbia University’s Teachers College where her work focuses on the education of the African Diaspora.

Published on June 20, 2014 09:39

June 19, 2014

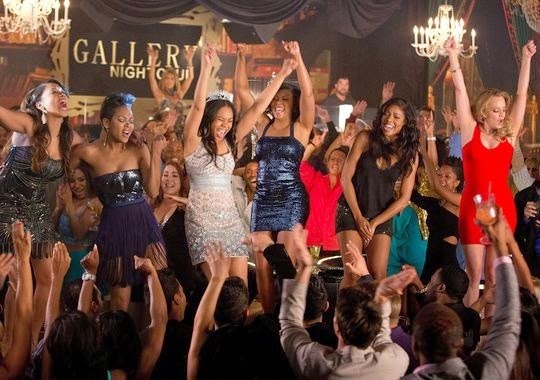

Ladies Night: Review of ‘Think Like a Man Too’ by Shana L. Redmond

Ladies Night: Review of ‘Think Like a Man Too’

by Shana L. Redmond | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Ladies Night: Review of ‘Think Like a Man Too’

by Shana L. Redmond | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)I have never seriously considered thinking like a man. Beyond a rejection of the homogeneity embedded within the demand that I think like a man (read: any man) and a recognition that your definition of “man” and mine may be very different, I also question the suggestion that the act of thinking like a man is at all beneficial. Don’t get me wrong; I rely on the thoughts of thoughtful men every single day. For example, I truly, hand to heart, believe Harry Belafonte (a man) when he sings, “man smart, woman smarter.” I even sing along (loudly). Some of my best friends are men (to whom I listen on occasion). My refusal to think like a man stems then not from any dislike for the way that certain men think but from the simple truth that I like the way that I think better.

Of course, I recognize that most women are not socialized this way and wider society reflects the reasons why. As majority (if not exclusively) male state and federal committees continue to debate and legislate women’s health, including abortion and contraception, we are similarly faced with a popular culture that tells women who and what we are, when and where we should be, and why we should be grateful for the limited access and representation that we receive. The premise of the Think Like a Man (TLAM) franchise—composed of a best-selling book by comedian Steve Harvey and two major film releases by director Tim Story—follows in this logic by telling Black women, in particular, that our capacity for rigorous and strategic thought is limited, flawed, and, ultimately, disadvantageous in our efforts to attract and keep not just Black men, but any men.

Though ripe for the picking, I’m going to forgo engagement with debates of Enlightenment thought and rationality as a colonial enterprise; I do, however, want to note just a couple of the more apparent and pressing concerns of these productions as they are the common sense of the films’ influence. TLAM & Think Like a Man Too (TLAMToo) suggest that Black women—as a monolith—are singularly motivated by our primordial instinct to mate and nest with the male species, which additionally assumes that we are basic heterosexuals—monogamous and unqueer. TLAMToo even uses prison scenes—for both the men and the women—to announce (without provocation) the characters’ proximity to but repudiation of homosexuality. Both films also suggest that for women, emotions can be our strength but are most often our weakness, requiring that we be trained to thinkin a particular, even singular, way. This was an especially prominent storyline within the original film.

The Achilles heel of the beautiful, hyper-professional business mogul Lauren (Taraji P. Henson) in TLAM was her stubborness, which nearly ended her relationship with the gorgeous and underemployed chef Dominic (Michael Ealy). By the end of the film, she is the final hurdle that the rom-com must overcome; her display of conciliation at the very end of the film, in full view of their friends and his food truck patrons, shows that the game of love is a tactical one that requires women to lose in order to win.

Men clearly have home court advantage in both films; the very lexicon of the game solidifies the films’ placement within a sphere of male dominance, even as women’s characterizations mature in the sequel. Though the game metaphors continue in TLAMToo—women and men are on “opposite teams,” the men commit “turnovers” that leave them vulnerable to the women, and, at some point, all characters find the “score tied”—the strategy in the “battle of the [two] sexes” was underplayed this time around. Gone is Harvey’s installment as an ‘impartial’ referee who reminds the audience of the rules of engagement. TLAMToo instead shows us what the characters have learned as all five couples, plus a solo Cedric (Kevin Hart) and Sonia (La La Anthony), travel to Las Vegas for the wedding of Candace (Regina Hall) and Michael (Terrence J).

Like The Best Man (1999) before it, the film does not privilege the nuptials—it instead develops an escalation of raucous scenes drawn from the bachelor and bachelorette parties. Beginning with a reprise of Tom Cruise’s famous Risky Business scene by Cedric in his posh hotel suite and “high tea” for Candace (complete with a deflated “Idris” blow-up doll) planned by Michael’s disapproving mother Loretta (Jenifer Lewis), the inevitable comedy of errors leads to consistent laughs built from Hart’s spot-on exaggeration and timing as well as the ensemble cast’s ability to reference and reinvent defining Black popular culture moments of our generation.

By losing Harvey and formal ties to his book, TLAMTooprovides more space for the women—this time joined by Tish (Wendi McClendon-Covey), the dowdy wife of Bennett (Gary Owen)—to determine their pleasure, no matter how cliché. They are the ones who most thoroughly develop the audience’s tie to the Black popular culture of the past, in the process breaking the fourth wall and provoking the head nods, applause, and call and response that only comes from mutual recognition.

The fully three-minute plus rendition of Bell Biv DeVoe’s “Poison,” which the women perform from bar tops, VIP banquettes, and a fluorescent-lit room shot with a fisheye lens (a la Puff Daddy and Mase), was the climax of a ladiesBy the time that both parties reunite and resume their normative lives, the women have already exhibited their independence, having traveled back to the 90s in order to enjoy their present. Where that freedom will take the characters next is unclear, although I am confident that we will see them all again. Until then, it would be worth reimagining the premise of the films: instead of requesting that women Think Like a Man, I think (like a woman) that it would be a far more provocative and liberatory gesture to encourage men to Party Like a Woman.

***

Shana L. Redmond is Associate Professor of American Studies and Ethnicity at USC. She received her combined Ph.D. in African American Studies and American Studies from Yale University. Her research and teaching interests include the African Diaspora, Black political cultures, music and popular culture, 20th century U.S. history and social movements, labor and working-class studies, and critical ethnic studies. Her book, Anthem: Social Movements and the Sound of Solidarity in the African Diaspora , examines the sonic politics performed amongst and between organized Afro-diasporic publics in the twentieth century. Her current project details the performative regimes of aid music.

Published on June 19, 2014 20:21

The Place of Afro-Brazilian Women in the World Cup

Photo Credit: Melissa Creary

The Place of Afro-Brazilian Women in the World Cup

by Melissa Creary and Erica Lorraine Williams | HuffPost

Photo Credit: Melissa Creary

The Place of Afro-Brazilian Women in the World Cup

by Melissa Creary and Erica Lorraine Williams | HuffPostSomos um só . The commercial released by Globo, Brazil's largest communication network, begins with a pair of soccer cleats draped over a power line and ends with a large crowd cheering a soccer game in front of a television. The commercial features a series of images that render Afro-Brazilians nearly invisible. Watching it, one quickly comes to understand that -- much like the myth of racial democracy -- "We are One" is more an aspiration than a reflection of the Brazilian reality. In a nation that has long had a troubled relationship with blackness, it is perhaps no surprise that Afro-Brazilians are nearly erased from the images of exuberant Brasileiros enjoying the World Cup.

Brazil has a long history of constructing discourses of national unity, while simultaneously pushing their black and indigenous populations to the margins. Since preparations for the World Cup began in Brazil, there have been stories of demolitionand pacification to enhance a façade of modernity and unity. But behind this façade are protests, police violence, power outages, water shortages, and a general disregard for those not considered elite. As Black American scholars who have resided in Brazil over a number of years in total for our respective research, we occupy a unique position and have witnessed the antithesis of the image of Brazil that Globo and others are trying to present to the world. We have access to both worlds of the privileged and the underserved and have observed how race, gender, and class play out literally and figuratively in the shadows of the world's most global game.

It was in Salvador, Bahia, in a Havaianas store that Melissa saw a display dedicated to the World Cup. Spain, England, USA and France, were displayed and below these rows, she viewed the city-specific sandal for Salvador. Each host city has its own sandal design and the soles of the sandals feature images of the major characteristics of each city. The Salvador sandal featured the architectural landscape of Pelourinho(an UNESCO historic site), the Havaianas themed ribbons likened to those found at the church of Nosso Senhor do Bonfim, and an adorned rubenesque woman in white headdress and clothing. In her hands she is holding acarajé, the traditional dish of Salvador. Although her skin is green and yellow, it is clear that she is a black woman -- a baiana de acarajé.

Baianas de acarajé are a symbolic representation of Africa in Brazil. Acarajé is an African derived food item made of fried ground black-eyed peas formed into fritters. Fried in dendê (palm oil) and made and sold on the street, acarajé is usually accompanied by dried shrimp, a tomato & onion salad, and a pasty condiment calledvatapá. As a food offering for the orixá Iansã, acarajé is closely associated with the Afro-Brazilian religion Candomblé. Vendors of acarajé are almost exclusively Afro-Brazilian women, and many are Candomblé adherents.

Salvador, capital of the state of Bahia in the Northeast of Brazil, is known for being the most "African" city in Brazil due to its large Afro-Brazilian population and strong preservation of Afro-Brazilian culture. In Brazil, the commodification of blackness is pervasive and longstanding. The marketing of blackness is central to Bahia's place in the transnational tourism industry. For example, we can see this in the historic city center where people pay to take a picture dressed as a baiana de acarajé or acapoeirista with faux dreadlocks.

The image of an Afro-Brazilian woman on the sole of a flip-flop to be walked upon is deeply political, economically charged, and troubling. The contradictions surroundingbaianas de acarajé in Salvador are emblematic of the persisting marginalization of black women in contemporary Brazil. Although baianas de acarajé are considered an integral part of Bahia's cultural patrimony, they have been engaged in a battle with FIFA over the past few years just to be allowed to sell their Bahian delicacies at (or within two kilometers of) the Fonte Nova stadium (so as not to compete with McDonalds, one of the sponsors).

After much protest by the Association of Baianas de Acarajé and their supporters, FIFA agreed to allow a limited number (six) of baianas to sell acarajé inside and around the stadium in June 2013. The images on the Havaianas sandal and in the correspondence of FIFA Weekly reiterate and perpetuate the historical roles to which black women have been relegated in Brazil – the erotic/exotic and the domestic/labor.

Erica's latest project has involved speaking with black activist women based in Salvador who are fighting to claim recognition beyond domesticity and exoticism. In much of the World Cup imagery, Afro-Brazilian women are featured as erotic resources necessary to ensure a successful and fulfilling trip to Brazil. This is evident in a recent travel tip document created by FIFA for tourists to Brazil. It features an image of two brown-skinned women lying stomach-down on the beach. Scantily-clad in Brazilian bikini bottoms, the women lay watching as a group of men play an exuberant game of futebol. Though this image is based in Rio de Janeiro, it fits with many of the tourism advertisements Erica found in her previous research on sex tourism, in which black women's bodies are featured as an integral part of the lure of Bahia.

These examples have urged black women's organizations across Brazil to organize to march on Brasília for the Marcha das Mulheres Negras Contra o Racismo, Violência e Pelo Bem Viver (March of Black Women against Racism, Violence and for Living Well) in March 2015. It is a step, they hope, in garnering attention for an often neglected population.

While World Cup propaganda attempts to unify the Brazilian nation under the flag of the "national religion" of futebol, this reinforced national unity consists of the same forces of gendered racism and inequality that continue to separate Brazil.

***

Melissa Creary is an interdisciplinary scholar and PhD Candidate in the Institute for Liberal Arts at Emory University. Her area of study includes history of medicine, genetics, race, health policy, and culture. Currently, Melissa is a 2013-2014 Boren Fellow and is residing in Brazil for a year of fieldwork.

Erica Lorraine Williams is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at Spelman College. Her first book, Sex Tourism in Bahia: Ambiguous Entanglements (2013), won the National Women’s Studies Association/University of Illinois Press First Book Prize. Her current project explores Afro-Brazilian feminist activism in Northeast Brazil.

Published on June 19, 2014 04:25

June 18, 2014

Legendary Pianist Horace Silver Dies At 85

Published on June 18, 2014 17:51

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.