Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 608

June 10, 2016

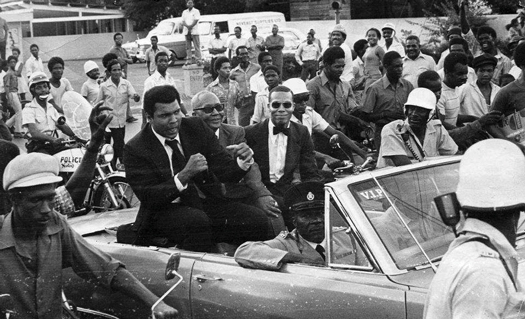

Dave Zirin on the Whitewashing of Muhammad Ali: He Wasn’t Against Just War, But Empire

'Dave Zirin, sports editor for The Nation magazine, joins +Democracy Now! from Muhammad Ali’s hometown, Louisville, Kentucky, where he will attend Ali’s funeral. Zirin recounts Ali’s activism against racism in the city and says, "[T]his funeral is, in so many respects, Muhammad Ali’s last act of resistance, because what he is doing is pushing the country to come together to honor the most famous Muslim in the world at a time when a presidential candidate is running on a program of abject bigotry against the Muslim people, and the other presidential candidate is somebody who has proudly stood with the wars in the Middle East."'

'Dave Zirin, sports editor for The Nation magazine, joins +Democracy Now! from Muhammad Ali’s hometown, Louisville, Kentucky, where he will attend Ali’s funeral. Zirin recounts Ali’s activism against racism in the city and says, "[T]his funeral is, in so many respects, Muhammad Ali’s last act of resistance, because what he is doing is pushing the country to come together to honor the most famous Muslim in the world at a time when a presidential candidate is running on a program of abject bigotry against the Muslim people, and the other presidential candidate is somebody who has proudly stood with the wars in the Middle East."'

Published on June 10, 2016 14:51

Bettina Love: On Black Girls + Discipline + Schools

'The schools attended by Black girls who live in poverty are often low-performing and too focused on discipline, explains researcher Bettina L. Love.' -- +Education Week

'The schools attended by Black girls who live in poverty are often low-performing and too focused on discipline, explains researcher Bettina L. Love.' -- +Education Week

Published on June 10, 2016 14:35

Installation; Martin Puryear--"Big Bling"

'This episode of +ART21 "Exclusive" follows the fabrication and installation of Martin Puryear’s monumental public sculpture "Big Bling" (2016). "There's a story in the making of objects," the artist told ART21 in an archival interview. "There's a narrative in the fabrication of things, which to me is fascinating."'

'This episode of +ART21 "Exclusive" follows the fabrication and installation of Martin Puryear’s monumental public sculpture "Big Bling" (2016). "There's a story in the making of objects," the artist told ART21 in an archival interview. "There's a narrative in the fabrication of things, which to me is fascinating."'

Published on June 10, 2016 14:22

BKStories: Father-Daughter Publishing Team Publish Children's Guide to Brooklyn

'Daddy Daughter Publishing's latest book

Dreaming About The Many What To Do's While In Brooklyn

" is a young tourist's guide to Brooklyn. The publisher was created by father and daughter team, Amber and Ephraim Benton. '

'Daddy Daughter Publishing's latest book

Dreaming About The Many What To Do's While In Brooklyn

" is a young tourist's guide to Brooklyn. The publisher was created by father and daughter team, Amber and Ephraim Benton. '

Published on June 10, 2016 14:07

#CodeSwitch: Being 'Outdoorsy' When You're Black Or Brown

'On this episode of the Code Switch Podcast, contributors Shereen and Adrian take a look at why being "outdoorsy" can get complicated when you're a person of color in America.' -- +NPR

'On this episode of the Code Switch Podcast, contributors Shereen and Adrian take a look at why being "outdoorsy" can get complicated when you're a person of color in America.' -- +NPR

Published on June 10, 2016 06:19

#TheSpin: Style in the Struggle--Fashion as Resistance + Liberation + Armour

Jamie McCarthy/FilmMagicOn this episode of #TheSpin with host Esther Armah, she is joined by journalist

Hannah Azieb Pool

and historian

Tanisha C. Ford

in a conversation about the politics of style. The guests examine the responses to Lupita Nyong'o recent hairstyle and the style of Black men such as Muhammad Ali, Prince and Fela Kuti.

Jamie McCarthy/FilmMagicOn this episode of #TheSpin with host Esther Armah, she is joined by journalist

Hannah Azieb Pool

and historian

Tanisha C. Ford

in a conversation about the politics of style. The guests examine the responses to Lupita Nyong'o recent hairstyle and the style of Black men such as Muhammad Ali, Prince and Fela Kuti.

Published on June 10, 2016 06:11

Down the Road to a Burning Planet: How Fracking Bypassed Democracy

'Activist Wenonah Hauter reviews the series of policy decisions and industry consolidation that set the course for America's current fracking boom, and explains why fracked natural gas is not a "bridge fuel" as politicians claim, but a backwards route away from renewable energy, and how collective action is America's only hope for steering the country off the dirty, disastrous course charted by politicians, business interests and (surprisingly) mainstream environmental groups. Wenonah is author of

Frackopoly: The Battle for the Future of Energy and the Environment

.' --

This is Hell Radio

'Activist Wenonah Hauter reviews the series of policy decisions and industry consolidation that set the course for America's current fracking boom, and explains why fracked natural gas is not a "bridge fuel" as politicians claim, but a backwards route away from renewable energy, and how collective action is America's only hope for steering the country off the dirty, disastrous course charted by politicians, business interests and (surprisingly) mainstream environmental groups. Wenonah is author of

Frackopoly: The Battle for the Future of Energy and the Environment

.' --

This is Hell Radio

Published on June 10, 2016 05:55

June 9, 2016

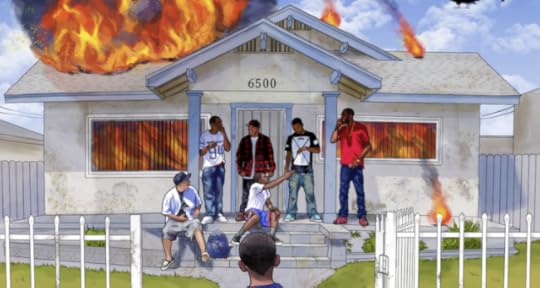

#DontSleep Series: Vince Staples, Hell Can Wait

#DontSleep Series: Vince Staples, Hell Can Waitby Lawrence Ware | @Law_Ware | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

#DontSleep Series: Vince Staples, Hell Can Waitby Lawrence Ware | @Law_Ware | NewBlackMan (in Exile)In 2015, Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly took the world by storm. The break out song from the album, “Alright”, was ubiquitous. It became the song of the summer. Yet, it was an EP released by a different California artist that captured my attention. The little known 2014 release enthralled me with its sonic cohesion and Sartrean nihilism. The album was Hell Can Wait, and the artist is Vince Staples.

Hailing from Long Beach, the home of Snoop, Staples wasn’t feeling the cheerful, club banger turn in hip-hop prior to 2014. “If you listen to shit about niggas being in a position where they have no hope, there should be nothing at peace about that,” he said in an interview with Pitchfork. “There’s a way to do it where it’s listenable and likable, but it shouldn’t just be some happy stuff.” Hell Can Wait (HCW) is the perfect aesthetic expression of that sentiment. The sometimes-soulful production is laced with lyrics that cut to the bone.

Unlike Lamar, Staples is not a dense lyricist in the tradition of Nas or Biggie. His stripped down style has a decidedly West Coast feel that owes more to Ice Cube and Tupac Shakur. He does not make you wonder about the subject matter of the album. In the chorus of “Fire”, the first song on the EP, he whispers over the chorus: “I’m probably finna go to hell anyway.” This nihilism colors all that comes thereafter.

HCW wrestles with the difficult moral choices people trapped in urban decay are forced to make. He does not comment on what gives rise to this decline; instead, he focuses upon what is experienced by those forced to live under the weight of institutional racism and economic inequality. This is a sonic tour through a museum of black misery. He investigates the psychology of men and women who have accepted their reality as inescapable and are fully invested in the underground economy the streets offer.

“65 Hunnid” discusses the loneliness inherent in a life on the streets. On the track, he says, “Car full of niggas, but you’re alone” yet, paradoxically, he says, “time to show how much you love your homies …” The need for acceptance coupled with the distance necessitated by life on the streets cultivates a sensation of paranoia.

“Screen Door” uses the hook from Goodie Mob’s “Cell Therapy “as the skeleton upon which to flesh out the ramifications of a childhood filled with infrequent visits from drug addicts seeking the respite from reality his father offers.

Next is “Hands Up”, a song that examines the difficult relationship people living in an area full of crime share with those who are sworn to serve and protect them. The contemptuous relationship described in “Hands Up” makes us sympathetic to his plight; yet that sympathy is complicated by the threat Staples poses to his community since, as we discover in “Blue Suede”, he is a member of the Long Beach Crips.

Yes, Staples is in an impossible economic situation—the land of “babies having babies;” therefore, the choices he makes are never easy ones. Sure, a college education would have been preferable, but given his immediate need, he turned to crime—a life lived in powder blue Air Jordan 3s, attire that reflects his loyalty to the gang.

The penultimate song on the EP would be blatantly misogynistic if Staples were a less insightful rapper. He begins by discussing the sexual escapades of black men who clearly view women as merely an object of sexual gratification; however, he ends the song by considering the view of love and sex from the perspective of women who are reared in an inner city milieu. The possibility of intimacy for black men and women are endangered by the institutional forces weighing down on them. One must be careful and protect their hearts, because if you “fall in love, you’re lost.”

The album ends with a summarization of all that came before. His nihilism is put on full display through spare lyrics and dizzying flow. This was an EP that, for many, put Vince Staples on the map. His follow-up, 2015’s Summertime ’06, is brilliant, but a bit verbose. Hell Can Wait is a tour de force. An album that is as much sociology and philosophy as it is art.

It’s almost as if Richard Wright stepped into the booth to lay down bars.

In Native Son, Wright writes: “Goddammit, look! We live here and they live there. We black and they white. They got things and we ain’t. They do things and we can’t. It’s just like living in jail.” Vince Staples reminds us that the inner city still imprisons many. We should never forget that for some living in those conditions the day-to-day lived experience is one of anxiety and moral ambiguity. Some are so burdened by life that the choices they make are colored by the feeling that they “prolly finna go to hell anyway.”

+++

Lawrence Ware is an Oklahoma State University Division of Institutional Diversity fellow. He teaches in OSU’s philosophy department and is the diversity coordinator for its Ethics Center. A frequent contributor to Counterpunch and Dissent magazine, he is also a contributing editor of NewBlackMan (in Exile) and the Democratic Left. He has been a commentator on race and politics for HuffPost Live, NPR’s Talk of the Nation and PRI’s Flashpoint. Follow him on Twitter.

Published on June 09, 2016 09:30

June 8, 2016

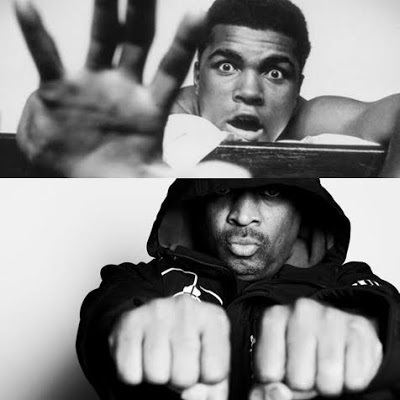

Edge of Sports: Chuck D Honors Ali--“He Grabbed the Mic and He Rhymed”

On this episode of

Edge of Sports

, host Dave Zirin is joined by Chuck D, who talks Muhammad Ali and his supergroup ‘Prophets of Rage,’ which also features B-Real from Cypress Hill and members of Rage Against The Machine.

On this episode of

Edge of Sports

, host Dave Zirin is joined by Chuck D, who talks Muhammad Ali and his supergroup ‘Prophets of Rage,’ which also features B-Real from Cypress Hill and members of Rage Against The Machine.

Published on June 08, 2016 20:24

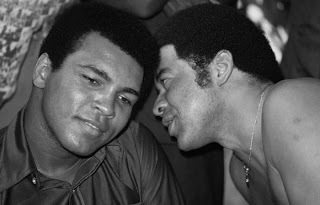

Muhammad Ali and the “Birth” of Black Digital Archive by Mark Anthony Neal

Muhammad Ali and the “Birth” of Black Digital Archiveby Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Muhammad Ali and the “Birth” of Black Digital Archiveby Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan | NewBlackMan (in Exile)It is not too ostentatious of a boast; whether Muhammad Ali “floated” like a butterfly of “stung” like a bee, he was without doubt, one of the most photographed men of the 20th Century. Like Frederick Douglass a century earlier, Ali understood the power of the photographic image. Ali was indeed “beautiful” and “pretty,” but as Henry Louis Gates, Jr. writes of Douglass he “not only used photographic images of himself, like he used his oratory—first in the battle to end slavery, and second to insure full citizenship rights for the Negro—but also theorized about photography, its nature and uses.” (Critical Inquiry, 2015)

Ali, though, had an accomplice, one who in his own right, at the peak of his notoriety, was one of the most photographed Black men of a generation. In the aftermath of Ali’s death, much has circulated with regards to his all-too-brief though powerful relationship with Malcolm X (with Sam Cooke and Jim Brown as fellow travelers). Politically linked as Ali’s “Blood Brother,” Malcolm X shared a passion for photography--and Ali was often his willing subject.

There is something striking about the subject of so much photography, being lensed so often with a camera in his hand or on his person. As Maurice Berger writes in his essay, “Malcolm X, Visual Strategist” the Nation of Islam Minister, “a keen steward of the Nation of Islam’s visual representation, Malcolm X often carried a camera...He relied on photographs to provide the visual proof of Black Muslim productivity and equanimity that sensationalistic headlines and verbal reporting often negated.” (New York Times, 2012).

Berger adds, “If Malcolm was a talented visual strategist behind the camera, he was nothing less than a prodigy in front of it. Well before the rise of photo ops and People magazine, he endeavored, with considerable sophistication, to prepare himself — and the community he led — for the penetrating, and often unforgiving, eye of the news media.” Indeed this is likely a sensibility that Malcolm X passed on to his friend Ali, whose obvious love of being in front of the camera was exploited in creation of a generous archives of now digital, material that provides so much depth into our understanding one of the most iconic figures of the 20th Century.

While much has been written and said about Ali’s verbal and cerebral acuity, Ali is less lauded for the way that his manipulation of his image could also be read as evidence of his intellectual prowess. In his book What’s My Name? Black Vernacular Intellectuals, Grant Farred observes “Ali reveled in the blackness of his body,” who as a “boxer was perforce required to display his body, but as a sports figure conscious of the history of the black body’s negative inscriptions, he drew attention to his physicality as a sociopolitical commodity to be enjoyed and consumed by all Americans.”

Ali has been the subject of many photographic collections--Benedikt Taschen’s GOAT being one of the most well-known (and expensive). And of course, one of Ali’s closet friends and confidantes was photographer Howard Bingham, who published his own collection Muhammad Ali: A Thirty Year Journey, in 1993. Bingham’s photos like those of Malcolm X are significant for the methods in which they capture BlackSpace -- what we might think of that conflation of private Blackness with the interiorities of Blackness -- those embodiments not necessarily intended for consumption, but rather to be loved, and adored and desired in the intimacy of Black Lives.

In this regard those images of Ali--relishing in the contours and crevices of what have been simply described at the time as the Chitlin’ Circuit--resonate with a generation of young Blacks for which hand-held devices and visual platforms such as Instagram and Snapchat have reimagined the Black visual archive in a digital moment marked by a devotion to the intimacy of Black Bodies across time, space and place.

Whereas some might see the ways that Blackness has encompassed social media as emblematic of the limits of so-called hyper-consumption (tethered to legitimate concerns about the Surveillance State), Krista Thompson, suggest “private consumption may be seen as indicative not of the demise of the political but of the changing ways people represent their interests in the face of widespread disenchantment with long-standing political institutions, which have changed the meaning and possibilities of politics.” (Shine: The Visual Economy of Light in African Diasporic Aesthetic Practice, 30).

Whereas some might see the ways that Blackness has encompassed social media as emblematic of the limits of so-called hyper-consumption (tethered to legitimate concerns about the Surveillance State), Krista Thompson, suggest “private consumption may be seen as indicative not of the demise of the political but of the changing ways people represent their interests in the face of widespread disenchantment with long-standing political institutions, which have changed the meaning and possibilities of politics.” (Shine: The Visual Economy of Light in African Diasporic Aesthetic Practice, 30). What those Malcolm X’s photographic practices and Bingham’s photography of Muhammad Ali anticipate is what Thompson describes as “popular visual practices” that “generate new subjectivities and configurations of the political in what might be considered a post-rights-era, when the expectations surrounding rights fought for in the immediate postcolonial and post-civil-rights era seem to some unfulfilled.” (31)

***

Mark Anthony Neal is the author of several books including Looking for Leroy: Illegible Black Masculinities (NYU Press, 2016). He is the host of the weekly video podcast Left of Black and curator of NewBlackMan (In Exile). Neal is Professor of African + African-American Studies and Professor of English at Duke University.

Published on June 08, 2016 20:03

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.