Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 1031

January 14, 2012

"Race is an Economic Coding System": Walter Mosley @ BAM

[image error]

Published on January 14, 2012 05:23

January 13, 2012

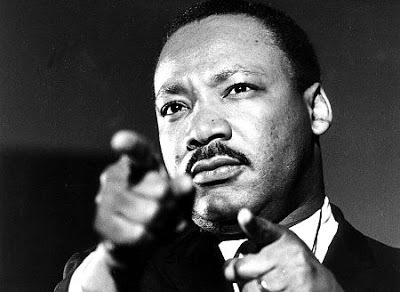

The Mixtape "King"

TheMixtape "King" byMark Anthony Neal | NewBlackMan

Twoof my favorite images of Martin Luther King Jr., are not of actual images ofKing at all. They are of actorJeffrey Wright in his performance of King from the HBO original film Boycott, directed by Clark Johnson. The first scene occurs nights beforethe launch of the Montgomery bus boycott and King and Ralph Abernathy(portrayed by Oscar nominatedactor Terrance Howard)—the duo functioning more like running partners—dispatchthemselves to local pool halls to get the word out about the bus boycott, onthe premise that, "not everybody goes to church."

Thegesture itself is not all that important, but the film presents an image ofKing that suggest how seamlessly he might have integrated himself into whatmany might have thought—at least at the time—as fairly disparate spaces; apoint that was not lost on the film's characters who were hustled into a gamesof pool by the otherwise devout servant of the Lord—and his people.

Thesecond image occurs during the film's closing credits. With the film's versionof King's legacy assured, we see King in contemporary Montgomery, holding courtwith a bunch of corner boys—young African-American men—seemingly physically,and perhaps, rhetorically at home with the denizens of the Hip-Hop generationat the turn of the 21st Century.

Inthis scene it is not unimaginable to imagine this King doppelganger, rolling upon this group of would be thugs—legible in that way to far too many casualobservers—and greeting them with the gesture "Lil Nigger, Just Where You Been?". This is, of course, part of the privateKing—the King that played the rhetorical dozens with his inner circle, the Kingwho sought sexual release in the afterhours of public life, the King that hasbecome most relatable to those generations, who've only known him as a deadicon and a ready made postage stamp.

AsMichael Eric Dyson notes in his book IMay Not Get There With You: The True Martin Luther King, Jr., the "rulesfor public discourse for blacks have changed from the fifties…neither iscursing an automatic sign of unintelligence or unrighteousness. Those stereotypes must be broken up inorder to open communication between the civil rights and hip-hop generations." AsJonathan Rieder suggests, the "sublime and decorous universalism" that definedthe public King, "never encompassed the entirety of King's repertoire of talkan identity."

Rieder'sessay "What Kind of People Worship Here? The Labor of Legitimacy and thePassion of Prophesy in 'Letter from Birmingham Jail'" is focused on King'sdexterity at speaking to multiple publics, most often one Black and oneWhite. The King that Riederpresents us, is one who is highly skilled at navigating these distinct publicsor what some social scientists have called parallel publics; one who deftlygestures across race and religion, who, as Rieder describes it, "glides fromgentility to rudeness and from the labor of legitimacy, to the passion ofprophecy." This is the King, whoneeded the comforts of community, to whoop it up, when the reporters were gone,and he needed to recover from the rhetorical pirouettes that were as necessaryto the forwarding of the freedom struggles as the direct action that took placein the streets.

Inmany ways the translation of this King to the hip-hop generation is not anempty or simple conceit; The King that Rieder give us—the King who some viewwith suspicion because of his liberal borrowing of ideas in that doctoraldissertation—is the King who functions like a skilled turntabalist, dutifullymixing and remixing narratives of freedom, resistance and redemption—forhimself and the nation; A King whois at home with the sampling practices that have come to define the sonicgenius of rap music production, both part of a broader continuum of Blackexpressive culture that privileges borrowing, sharing, and the refashioning ofstyle and ideas. Like Sean "PuffyDiddyDaddy" Combs boasted a decade ago, "weinvented the remix."

AsRichard Schur writes in his book Parodiesof Ownership: Hip-Hop Aesthetics and Intellectual Property Law, "Sampling is not simply the reshapingand reuse of recorded text, but a method of textual production…that proceeds bylistening for and incorporating discrete parts, rather than completed wholes,and constructing an aesthetically satisfying text out of them."Partof King's genius, was not simply his ability to speak across disparate publics,but to do so in a way that was aesthetically pleasing within thesepublics. Yes, this is, as Riedersuggest, the crossover King—the King we remember every January, who getsinvoked in visual mashups with Malcolm X and President Barack Obama.

Yetwe still have this private King—the barbershop King, shooting the shit with his"lil Niggers"—well offstage, sometimes into the afterhours, on drives acrossthe South, in hotel rooms where they are partaking in the fruits of theirsegregated celebrity.

Thisis the mixtape King—the King that circulates to check the temperature of hisstreet cred, the King who inspired those with no vested interest in theinstitutions and institutional figures, including King, who spoke for them, butinstead simply appreciated the Swag, both rhetorical and political. And perhaps it is this mixtape Kingthat we all might also consider.

***

Mark Anthony Neal is the author of several booksincluding the forthcoming Looking forLeroy: (Il)Legible Black Masculinities. He is professor of African& African-American Studies at Duke University and host the weekly videowebcast Left of Black . Follow him onTwitter @NewBlackMan.

[image error]

Published on January 13, 2012 20:28

Private Prisons Pimp the People

Private Prisons Pimp the People by Lamont Lilly |special to NewBlackMan

Here in America, ourgreat "land of the free," there are approximately 130,000 inmates now housed inprivately owned prisons. It's a foul stench within a justice system that leadsthe world in number of persons incarcerated within a state, federal or privateinstitution. Our latest tally of 2 million equates to 25% of the globe'sincarcerated population. This massive waste of human life is commonly known as thePrison Industrial Complex, an oppressive current now being led from the topdown by the highly profitable Prison Privatization Movement. Its roots can betraced back to the 1980's of Ronald Reagan, his "War on Drugs" and toughersentencing platform. Due to policy makers' concerns of prison overcrowding atthe time, in 1984 the Corrections Corporation of America was contracted tooversee its first facility in Hamilton County, Tennessee. Such transitionmarked a new federal precedent of complete private control of a correctionalinstitute.

Though depicted ascost-saving efficient operations, independent studies suggest the contrary. Alack of regulation enables smaller staff and inadequate training, in turn,producing more violence and consistently unstable conditions among those whoseek to "serve time" responsibly. Sustainable medical care has also come intoquestion. Private prisons like the George W. Hill Center, Walnut Grove YouthFacility and New Castle Correctional Institute have garnered a barrage ofrecent scrutiny over the deaths of dozens of inmates. And though touted asinexpensively designed, private prisons have proven just as costly to constructas those categorized as public. Even more unnerving, such misguided controlsounds eerily similar to the Black Belt's Convict Lease System of the late 1800's,a state-run practice throughout the south that forcibly extracted free laborfrom newly emancipated slaves deemed "criminal."

Just as then, thesame companies grossing billions from the capture and incarceration of Americancitizens (mostly poor, Black and Latino) are the same brokers who donatemillions to state senators, school boards, mayors and police chiefs. It's no secretthat private firms such as The GEO Group possess direct appeal to federallegislation like "Three Strikes" and Mandatory Minimum Sentencing. Common sensesays such merging complexities spell corruption—political dividends too closefor public comfort. Meanwhile, predatory investors like Wells Fargo, AmericanExpress and Merrill Lynch reap robust returns on private bond purchasing—thesame greed-driven giants literally "banking" on the results of Black boys andtheir 4th grade EOG's. (The Children's Defense Fund details this associationthrough its Cradle to Prison Pipeline Campaign). As far as the diversityof stock in such regressive investments, additional stakeholders include a slewof corporate sponsors: Nordstrom's, Microsoft, IBM, Revlon, Target, Dell, Hewlett-Packardand even AT&T, a smorgasbord of some of your favorite brands.

Fact is, we as Americansaren't committing more crime; we're doing more time because it pays. In a way, such structural manipulation isalmost worse than chattel slavery, considering America's global claim to moral Democracyat its highest order—an order not far removed, it seems, from Nazi Germany'sconcentration camps at Warsaw and Auschwitz. We're talking "Third World"sweatshops disguised as rehab programs, possibly in your home state!

The Human Rightsinfringement of privatization isn't punishing someone who does wrong; it'sprofiting from the pain of that punishment, exploiting the limited freedoms ofinhumane confinement, maximizing such restrictive conditions for capital gain—thesame profits that merely perpetuate the incarceration of more citizens forlonger periods of time. I won't even mention the effects of exploited prisonlabor on the working class. While poverty in the U.S. continues to plague thegeneral public, highly-skilled positions are going for $1 an hour in theprivate prison sector. No wonderwe can't find jobs; our furniture and home appliances are being produced by rent-a-slaves,now. I hope this isn't what Big Business means by "Made in America." If so, I don't want no parts of it.***

Lamont Lilly is a contributing editor with the Triangle FreePress, who recently served as an organizer with Cynthia McKinney's, "Reportfrom Libya Tour." He is also a Human Rights Delegate with Witness for Peace andcolumnist for the African American Voice.[image error]

Published on January 13, 2012 19:43

Gil Noble Talks "Like It Is"

from the National Visionary Leadership Projec t:

Gil Noble, producer and host of the public affairs program "Like It Is," has interviewed famous African Americans like Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., Fannie Lou Hamer and Paul Robeson. During his career, he has worked to correct negative media representations of African Americans and has promoted ethics and objectivity in journalism.

Noble was born in Harlem to Jamaican immigrants Gilbert and Iris Noble. As a teenager, Noble was inspired by pianist Erroll Garner and decided to pursue a career in music. He formed the Gil Noble Trio and played in clubs around New York City while attending City College. After graduating, he worked for Union Carbide and modeled on the side. He met his wife Jean, also a model, during this time.

Noble attempted to break into broadcast by doing voiceovers and television commercials. He became a part-time announcer for WLIB, a Harlem radio station, in 1962. While at WLIB, he also reported, read newscasts, serviced the Associated Press teletype machine and tracked interview tapes. This experience gave him working knowledge of all aspects of a newsroom operation.

In 1967, Noble auditioned for a TV reporter position at WABC. On his second audition assignment, he was called to cover violence in Newark, New Jersey's Central Ward. Blacks had been shut off by a National Guard barricade while white city officials and journalists stood at the perimeter. Noble was able to cross the barricade and get the story from the black community's perspective. Because of his reports, he was hired. By 1968, he was anchoring weekend newscasts. At that time, WABC created a black-oriented program in response to the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Actor Robert Hooks was the host and Noble was the interviewer. When Hooks accepted an acting job, Noble replaced him as host. In the beginning, "Like It Is" focused on mostly entertainers, however, when Noble became producer in 1975, he turned its focus to the more serious issues of the black experience.

Over the years, Noble saw the documentary as the central focus and most rewarding aspect of his career. "Like It Is" has produced the largest collection of programs and documentaries on the African-American experience in the last half of the 20th century. He says documentaries "remain a powerful weapon to change false values, correct historical error and cure the poison of prejudice in the minds of black and white Americans."[image error]

Published on January 13, 2012 13:02

Brother Oustider: The Life of Bayard Rustin

California Newsreel :

To watch the entire documentary, to read background information and to order DVDs, visit:

http://newsreel.org/video/BROTHER-OUTSIDER-BAYARD-RUSTIN

This is a definitive film biography of one of the most controversial figures of the Civil Rights Movement. Hew was one of the first "Freedom Riders," an advisor to Dr. Martin Luther King and A. Philip Randolph, organizer of the 1963 March on Washington, intelligent, gregarious and charismatic, Rustin was denied his place in the limelight for one reason - he was gay.

Published on January 13, 2012 08:18

Obery Hendricks: Mitt Romney and the Curse of Blackness

Mitt Romney and the Curse of Blackness Obery M. Hendricks | HuffPost Religion

When it comes to others' choice of religions, I'm pretty much a live-and-let-live guy. In fact, I don't believe in religious litmus tests of any kind. Frankly, I think they are self-righteous and insulting. Yet I must admit that there is something about Mitt Romney's religion that I find deeply troubling, particularly in light of the possibility that he could become the next president of this nation. What concerns me is this: the Book of Mormon, the book that Mitt Romney and all Mormons embrace as divinely revealed scripture that is more sacred, more true, and more inerrant than any other holy book on earth, declares that black people are cursed. That's right. Cursed. And not only accursed, but lazy and aesthetically ugly to boot.

I'm not talking about ascribed racism such as we see in Christianity, in which racist meanings are attributed to certain verses of the Bible that actually contain no such meanings, as with the Gen. 9:25 cursing of Canaan (not Ham!) which, though used as "proof" of black wickedness and inferiority, in actuality has nothing to do with race.

And no, I'm not talking about a single ambiguous, cherry-picked verse, either. I'd much rather that were the case. The sad truth is that the Book of Morman says it explicitly and in numerous passages: black people are cursed by God and our dark skin is the evidence of our accursedness. Here are a few examples:

And I beheld, after they had dwindled in unbelief they became a dark and loathsome and a filthy people, full of idleness and all manner of abominations (1 Nephi 12:23).

"O my brethren, I fear that unless ye shall repent of your sins that their skins will be whiter than yours, when ye shall be brought with them before the throne of God. (Jacob 3:8).

And the skins of the Lamanites were dark, according to the mark which was set upon their fathers, which was a curse upon them because of their transgression and their rebellion against their brethren, who consisted of Nephi, Jacob, and Joseph, and Sam, who were just and holy men (Alma 3: 6).

It would have been infinitely more righteous if Mormons had relegated the sentiments of these verses to the scriptural sidelines of their faith, but the historical record tells us otherwise. Joseph Smith, Jr., the founder of Mormonism, repeatedly ordered his Church to uphold all slavery laws. Although Smith had a change of heart toward the end of his life, his successor, Brigham Young, did not. Young instituted social and ecclesiastical segregation as the Church's official policies, thus excluding people of black African descent from priesthood ordination and full participation in temple ceremonies, regardless of their actual skin color. Moreover, Brigham Young, whom Mormons revere almost equally with Smith, proved to the end of his life to be a brutal white supremacist who fervently supported the continued enslavement of African Americans; he was so convinced of black accursedness that he declared that if any Mormon had sex with a person of color, "the penalty, under the law of God, is death on the spot."

The Book of Mormon's teaching of the accursedness and, therefore, the inferiority of blacks -- if blacks are cursed, then by definition they are inferior to the divinely acceptable whites -- was reaffirmed by numerous Mormon leaders for a century and a half. As late as 1969, even after the Civil Rights Movement had dismantled de jure segregation throughout the land, David O. McKay, then president and "living prophet" of Mormonism, still publicly justified its segregationist policies by declaring that "the seeming discrimination by the Church toward the Negro... goes back into the beginning with God."

Now, some will argue that I should dismiss the codified racism of the Book of Mormon as the unfortunate folklore of a bygone era because of the 1978 revelation by Spencer W. Kimball, the Church's president and "living prophet" at that time, that after a century and a half black males were finally un-accursed enough to fully participate in Mormonism's priesthood and sacred temple ceremonies. However, even if we ignore the suspiciously coincidental timing of this "revelation" (it conveniently appeared when the Church's federal tax-exempt status was imperiled by its racial policies), an attentive reading reveals that Kimball's proclamation did not in any way address the question of whether or not the Church still considered the Book of Mormon's assertions of black inferiority to be divinely authorized. In fact, the specific contents of Kimball's revelation were never made public. Nor has the Church ever disavowed the Book's white supremacist passages or the past racist practices and pronouncements of its leaders.

What makes this all the more problematic for me is that at no time has Mitt Romney ever publicly indicated that he seriously questioned the divine inspiration of the Book of Mormon's teachings about race, much less that he has repudiated them. It is true that in a 2008 Meet the Press interview with the late Tim Russert, Romney did vigorously assert his belief in equal rights for all Americans in every facet of life. As part of that narrative, he cited his parents' "tireless" advocacy for blacks' civil rights, including the dramatic exit of his father, Michigan Governor George Romney, from the 1964 Republican convention as a protest against nominee Barry Goldwater's racial politics. He also shared that he wept when he learned of Spencer Kimball's aforementioned revelation. Yet from Romney's remarks it is not clear whether he wept for joy because Mormonism was eschewing its segregationist policies or if he wept from relief that the announcement promised to quiet the public outrage that those policies were causing. And significantly, while he recited his parents' efforts to confront racial injustice, Mitt Romney pointed to no such activities of his own.

But let me be clear: this is not a "gotcha" political ploy. In all honesty, I am neither saying nor implying in the slightest that Mitt Romney is a racist. I simply do not know that to be the case. Nor do I mean to overlook the racial progress that the Mormon Church has made in the last several decades. What I do mean to say is 1) that Americans of goodwill owe it to ourselves not to turn a blind eye to the possible implications of the white supremacist legacy of candidate Romney's religious tradition, no matter how noble our intentions; and 2) that Mitt Romney himself owes it to America to address the issue. Why? Because Romney was tutored into adulthood by a holy book that declares that all Americans like me are cursed by God. And he is not only a believer; he has served as a leader in his faith. This is indeed a crucial point for consideration because, as this nation has seen time and time again, the inevitable consequence of America's policy-makers considering people of color as inferior to whites is that blacks' social and material interests have also been considered inferior -- and quite often treated that way.

I admit that this question of religion and racism is quite complicated and I don't claim to have all the answers. But I do know that recognizing the equal rights of black Americans under the law, while of paramount importance, is not the same as recognizing our intellectual capabilities and moral character as inherently equal to whites. And I am aware of one thing more: that when Tim Russert invited Romney to repudiate his Church's racist legacy on Meet the Press, Romney refused.

That is why, Mr. Romney, as an American citizen whose president you seek to become, I must insist that you honestly and forthrightly attest to me and all Americans of goodwill that you actually can be my president, too, fully and completely. You can accomplish this by publicly disavowing the portions of your holy book that so sorely denigrate the humanity of me, my loved ones and all people of black African descent.

It is incumbent that you do this, candidate Romney, for the sake of all Americans.

*** Obery Hendricks is Visiting Scholar at Institute for Research in African-American Studies and Department of Religion at Columbia University and the author of the recent The Universe Bends Toward Justice: Radical Reflections on the Bible, the Church, and the Body Politic .

Published on January 13, 2012 08:07

"Freedom Rider," Etta Simpson Talks "Social Media"

From the Ella Baker Center :

In 1961, a group of young civil rights activists challenged segregation in the south by riding interstate buses. We had the pleasure of meeting one of the Freedom Riders .

Published on January 13, 2012 06:25

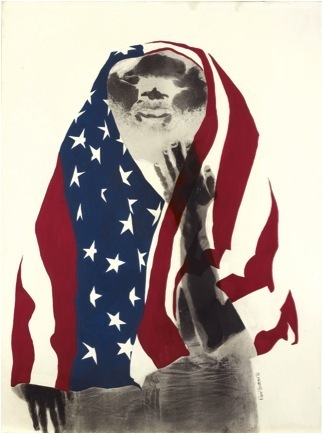

'Now Dig' Kellie Jones Talking About Art and Black Los Angeles

Now Dig Kellie Jones Talking About Art and Black Los Angeles by Tukufu Zuberi | HuffPost BlackVoices

I recently visited an art exhibit chronicling the legacy of art in Black Los Angeles. The show is at the UCLA Hammer Museum and is called "Now Dig This! Art & Black Los Angeles 1960-1980." I sat down to speak with the curator of the exhibit. Kellie Jones is associate professor in the Department of Art History and Archaeology at Columbia University. Her writings have appeared in numerous exhibition catalogues and journals. Her critically acclaimed book EyeMinded: Living and Writing Contemporary Art (Duke University Press 2011) has been named one of the top art books of 2011 by Publishers Weekly. Her project "Taming the Freeway and Other Acts of Urban HIP-notism: African American Artists in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s" is forthcoming from The MIT Press. Stay tuned for the rest of my interview with Kellie Jones tomorrow in my next post. Your latest show is at the UCLA Hammer Museum, "Now Dig This! Art & Black Los Angeles 1960-1980." Talk to me about the conceptual background of this show.

Well, the show came about because I was doing research on a book on African-American artists in Los Angeles. I was in Los Angeles and I ran into a friend who happened to be the chief curator of the Hammer Museum at the time, Gary Garrels. He said, "What are you working on?" I told him I was working on this book about L.A. And he said, "Oh, are you planning to do a show?" I told him, "One day, in the future." Two weeks later, he calls me and he says, "How about now?" So it turned out, there was this great opportunity with the Getty Foundation, the Getty Research Institute. They were offering seed money over a two to three-year period to do research on aspects of Southern California art. And would I like to put a proposal together to do a show based on my own research? I was already scheduled to go to the Getty to do an oral history for them with some of these artists, who ended up being in the show and are also in my book. So I said, "Great! Let's get going on this!"

Several of the works that you highlight in "Now Dig This!" come from the storage rooms of some of the major museums of art in the United States. In what way is this exhibition a philosophical shift from the typical show we might see at a museum of art?

I don't think it's that far off the mark of typical shows. I think what's different is that people are kind of shocked about all these artists that we didn't know about. And they happen to be African-American. This type of research goes into shows, generally, at certain institutions. If you look at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, or the Museum of Modern Art, these shows are based on a lot of research. The only difference then is that the focus is on African-American artists and what they were making at the time and how their work elucidates that time period. It's just another way to frame history.

Now, in your show, you've placed some of these artists in relation to the development of art in the United States more generally. For example, you placed David Hammons and Maren Hassinger and others in conversation with the experiments in multimedia and post-minimalism. Do you think the artists in your show were rebelling against the Western aesthetic tradition?

Yes and no. I mean, they're part of that tradition. They all went to art school, so they all have part of that. Minimalism was this kind of, more industrial, kind of cold, modernist thing. Generally in this kind of practice no sorts of extra meaning would come into the work outside the meaning of the materials themselves. But what post-minimalism did was that you could have materials that actually signified different things. So for David Hammons to use the greasy bag, for him, it meant places where people picked up chicken and the grease was running in the bag. And so, there you go. You know, for him, with hair, he thought he had found his perfect object. It was a black object. Yes, he thought this was a racial object. He used black hair, from black barbershops, and it was non-gendered. That's what he liked. So it didn't have to be about men or women. It could just be this black object. He also thought grease was a black object. Something that, you know, your mama tells you to grease your body up so you don't look ashy. So that these materials signified people's lives in history. For Senga Nengudi -- you didn't mention her, but she's also one of the people in that post-minimalist room -- she used pantyhose to talk about women's bodies. So we have a certain feminist idea. And then the sand. They're in L.A. You got a lot of sand at the beach. So you can get some sand. And that gave it a certain kind of volume, a certain kind of shape. Maren, now see Maren, she's interesting because she's using materials that are part of a minimalist canon -- that is steel, steel wire, rope -- but then she's making them into these kind of verdant forms. Of all the artists in the show, her work is not signifying something that would be "black," that would be considered "black art". But her performative practice does bring in African dance styles. They are working within a kind of canonical post-minimalism, but then at a certain point -- particularly Hammons -- they're bringing in things that are saying, this is about African-American life. This is about another side of life that you hadn't really considered, and that these kinds of materials allow us to think about.

Tukufu Zuberi is Chair and Professor of Sociology, University of Pennsylvania; host, PBS' 'History Detectives'

Published on January 13, 2012 06:13

January 12, 2012

Seven Minutes of 'Red Tails'

Published on January 12, 2012 07:44

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.