Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 1004

April 30, 2012

'That Funk': New Video by Jasiri X

FREE Download @ http://wanderingworx.bandcamp.com/album/jasiri-x-singles

directed by w.feagins, jr.

http://www.wfeaginsjr.com

Published on April 30, 2012 20:28

Chrishaun 'CeCe' McDonald: Black, Transgender Woman Faces Murder Trial as Supporters Allege Self-Defense

DemocracyNow.org

A transgender African-American woman is set to go on trial next week on charges of second-degree murder for an altercation after she was reportedly physically attacked and called racist and homophobic slurs outside a Minneapolis bar last year. Chrishaun "CeCe" McDonald received 11 stitches to her cheek, and was reportedly interrogated without counsel and placed in solitary confinement following her arrest. There were reports that the dead victim, Dean Schmitz, had a swastika tattooed on his chest. McDonald's supporters say the case is symptomatic of the bias against transgender people and African Americans in the criminal justice system. We speak with Raven Cross, one of McDonald's best friends, and Katie Burgess, executive director of Trans Youth Support Network.

Published on April 30, 2012 20:20

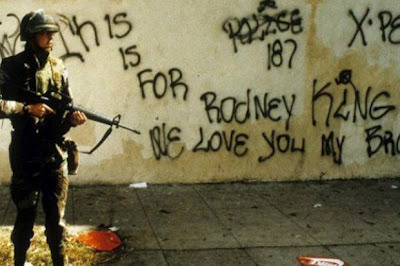

Left of Black S2:E30 | Remembering the LA Uprising: A Digital Mix

Left of Black S2:E30 | April 30, 2012

Remembering the LA Uprising: A Digital Mix

April 29th marks the 20thAnniversary of the week-long civil unrest popularly known as the LA Riots. Violence erupted throughout the city of Los Angeles in the aftermath of the acquittal of four LAPD officers who were accused of beating African American motorist Rodney King. The beating was famously captured on a held-held video device.

In this special episode of Left of Black, scholars, activists and artists reflect on the 20thAnniversary of the LA Riots including Marc Lamont Hill, Lynne d Johnson, Kimberly C. Ellis, Allison Clark, Kim Pearson, Moya Bailey, Blair LM Kelley, Christopher Martin(Play of Kid N’ Play), Treva Lindsey, Jasiri X, Michelle Ferrier, Jay Smooth and host Mark Anthony Neal.

***

Left of Black is a weekly Webcast hosted by Mark Anthony Neal and produced in collaboration with the John Hope Franklin Center at Duke University.

***

Episodes of Left of Blackare also available for free download in HD @ iTunes U

Published on April 30, 2012 15:27

Anatomy of a Black Radio Merger

A Radio Merger in New York Reflects a Shifting Industry by Ben Sisario | New York Times

On its surface, the merger last week of WRKS and WBLS, longtime rivals in the R&B radio format in New York, was business as usual for the broadcast industry. Two struggling competitors combined operations, and a deep-pocketed third party — Disney — came along to lease the leftover frequency.

But radio executives and analysts said the deal also reflected a broader trend in the business that has taken a toll on black and other minority stations. Since the introduction five years ago of a new technology for tracking audiences, many such broadcasters have experienced shrinking numbers, forcing radio companies to consolidate stations or switch to general-audience formats.

Arbitron, the standard radio ratings service, has long had sample audiences record their listening in a diary. In 2007, it began using the Portable People Meter, or P.P.M., a small electronic device that tracks radio signals, offering broadcasters far more precise listening data.

The technology, now used in 48 markets, has already had significant effects — for instance, increasing ratings for news and oldies stations. But many black stations have suffered under the new scheme, including WRKS, known as Kiss-FM, (98.7 FM) and WBLS (107.5 FM). While both were once ranked near the top of their desired demographic — adults ages 25 to 54 — since P.P.M.’s arrival they have slipped to between sixth and 11th place, said Jeff Smulyan, chief executive of WRKS’s parent, Emmis Communications.

“The recent economic downturn has affected the profitability of everyone in radio,” Mr. Smulyan wrote in an e-mail, “but the decline has been much more pronounced in adult African-American targeted stations, largely because of the impact of P.P.M.”

The deal to merge Kiss-FM and WBLS involves several broadcasters. Emmis sold Kiss’s intellectual property for $10 million to YMF Media, an investment group that is taking over WBLS. Disney, eager to expand its ESPN franchise, will lease Kiss’s old frequency for 12 years, paying a fee that starts at $8.4 million and increases 3.5 percent each year. The changes were scheduled to take effect at midnight on Monday.

Political figures, broadcasters and other industry observers have expressed concern over how the loss of stations will affect minority communities.

“I am saddened that an important black voice is going silent in New York City, especially during this important election year,” Tom Joyner, the syndicated talk-show host, said in a statement on Friday. “Although social media currently gets a lot of credit and rightfully so, nothing can replace the role black radio plays in empowering, informing and entertaining black people.” Mr. Joyner’s show was on Kiss-FM in New York but will not be on WBLS.

Last year, Radio One, which owns 53 stations, mostly in so-called urban formats — hip-hop, R&B, gospel and other genres popular with black audiences — changed stations in Houston, Cincinnati and Columbus, Ohio, from black to more general-interest formats, largely because of P.P.M. results, said Alfred C. Liggins III, the chief executive.

In response to complaints that P.P.M. undercounted minority listeners, Arbitron has settled lawsuits in New York and California, and pledged to improve its methods to find diverse sample audiences. But the company also stood by the accuracy of its ratings.

“Arbitron’s point of view is that P.P.M. is a more reliable and granular look at the marketplace,” Thomas Mocarsky, a spokesman, said on Friday. “Unlike the diary, which depended on recall, P.P.M. records what people are actually exposed to.”

Whether Arbitron’s new system will result in more changes for black stations is unclear. Emmis still owns WQHT-FM, (97.1) known as Hot 97, a top hip-hop station in New York, and Mr. Smulyan, the chief executive, said it had no plans to sell. Paul Heine, a senior editor at the trade publication Inside Radio, noted that some urban stations had been thriving under the system.

“There are a number of cities where we have two well-performing urban stations,” Mr. Heine said. “I don’t know if there’s going to be a domino effect.”

The companies behind WRKS and WBLS have also had troubles beyond simple ratings. Inner City Broadcasting, the previous owner of WBLS, went bankrupt last year. (YMF, the company buying it, is a new investment group including Ron Burkle and Magic Johnson.) WRKS’s revenue fell 32 percent in the last three years, according to a recent regulatory filing by Emmis Communications, and Mr. Smulyan said the station’s profit had fallen 90 percent.

Emmis, which has sold off a number of stations as it struggles with a heavy debt load, said its deal in New York to sell Kiss-FM and lease 98.7 to Disney was worth at least $96 million, and that it would help stabilize its balance sheet.

Some broadcasters rued the loss of black stations and the reduction of services to black communities that would result, but said the change had simply become an inevitable part of business.

“The economics of this business have changed so drastically,” said Mr. Liggins, of Radio One. “It is a shame. But something’s got to give.”

Published on April 30, 2012 07:58

April 29, 2012

Democracy Now: Will Cybersecurity Act Increase Domestic Surveillance, Violate Privacy Rights?

DemocracyNow.org

As it heads toward a House vote, critics say the Cyber Intelligence Sharing and Protection Act (CISPA) would allow private internet companies like Google, Facebook and Microsoft to hand over troves of confidential customer records and communications to the National Security Agency, FBI and Department of Homeland Security, effectively legalizing a secret domestic surveillance program already run by the NSA. Backers say the measure is needed to help private firms crackdown on foreign entities — including the Chinese and Russian governments — committing online economic espionage. The bill has faced widespread opposition from online privacy advocates and even the Obama administration, which has threatened a veto. We speak with Michelle Richardson, legislative counsel for the American Civil Liberties Union.

Published on April 29, 2012 19:12

Reflections on 20th Anniversary of the LA Riots on the April 30th ‘Left of Black’

Reflections on the 20th Anniversary of the LA Riots on the April 30th ‘Left of Black’

April 29th marks the 20thAnniversary of the week-long civil unrest popularly known as the LA Riots. Violence erupted throughout the city of Los Angeles in the aftermath of the acquittal of four LAPD officers who were accused of beating African American motorist Rodney King. The beating was famously captured on a hand-held video device.

In this special episode of Left of Black, several scholars, activists and artists reflect on the 20th Anniversary of the LA Riots including Marc Lamont Hill, Kimberly C. Ellis, Blair LM Kelley, Jay Smooth, Latoya Peterson, Kim Pearson, Christopher Martin (Play of Kid N’ Play), Jasiri X and others.

***

Left of Black airs at 1:30 p.m. (EST) on Mondays on the Ustream channel: http://www.ustream.tv/channel/left-of-black. Viewers are invited to participate in a Twitter conversation with Neal and featured guests while the show airs using hash tags #LeftofBlack or #dukelive.

Left of Blackis recorded and produced at the John Hope Franklin Center of International and Interdisciplinary Studies at Duke University.

***

Follow Left of Black on Twitter: @LeftofBlackFollow Mark Anthony Neal on Twitter: @NewBlackMan

Published on April 29, 2012 19:03

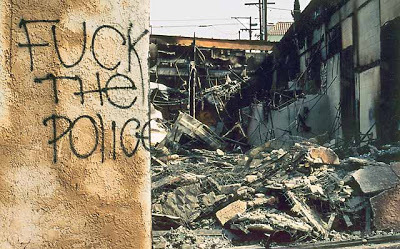

Reflections on a LA Rebellion and the Birth of the Digital Era

Reflections on a LA Rebellion and the Birth of the Digital Eraby Mark Anthony Neal | NewBlackMan

Amidst the images of violence, the fires that raged in the background and all of the allusions to earlier moments of insurrection—Watts in 1965 and Newark in 1967—my most lasting memory of the LA Riots was the watching the series finale of TheCosby Show on the evening of April 30th, 1992—a full day after the city erupted. As the Huxtables celebrated the college graduation of their only son Theo from New York University, the show that had defined Black Middle Class aspiration for nearly a decade and whose popularity made a claim on a post-race society before such language even existed, was revealed as flaccid in the face of the anger and betrayal of those that The Cosby Show ostensibly represented.

This disconnect was not without significance; The Cosby Show emerged as the most popular sitcom on television during an era—marked by the two term presidency of Ronald Reagan—that witnessed an outright assault on the Black poor and working class. For far too many Americans, The Cosby Show reflected the realityof Black life and possibility. Yet The Cosby Show had little to offer with regards to explaining the rage felt and exhibited by the young Black Americans that fueled the violence in Los Angeles and other cities across the nation. America would instead turn to generation of newly minted Black PublicIntellectuals and would be forced to finally take heed of the talking drums that had been ruminating in American cities for more than a decade in the form of rap music and Hip-Hop culture.

In his book The Black Fantastic, political scientist Richard Iton argues that the decade of the 1980s represented the beginnings of the hyper-visibility of Blackness. The popularity of The Cosby Show and YO! MTV Raps, along with the emergence of singular Black icons such as the late Michael Jackson, the late Whitney Houston, Eddie Murphy and Michael Jordan, were critical components of Black hypervisibility in the era. The beating of motorist Rodney King in March of 1991, along with the televised Anita Hill-Clarence Thomas Hearings in the fall of that year helped define what Black hypervisibility would look like at the dawn of the digital era.

King’s beating by LAPD officers—he was hit more than fifty times—was captured on a hand-held video device, and became a signature moment for the burgeoning digital era. As the video-taped beating became the most powerful evidence of what many Blacks and others understood as systematic (and perhaps systemic) violence by law enforcement officers against Black and otherbodies, that very same video-tape would be deconstructed in the court room a year later, leading to the acquittal of those officers on the basis that their violence was justified since King—unarmed and on the ground throughout—was incredulously resisting arrest.

The Digital era demanded a digital literacy, and a generation of Black scholars, many of them influenced by Black British theorist Stuart Hall, and Black and Brown journalists needed to re-tool in order to unpack the logic of the new media terrain. In her recent book, Uncovering Race: A Black Journalists Story of Reporting and Reinvention, journalist Amy Alexander recalls that “The LA riots…literally sparked my interest in media criticism.” Alexander like many Black journalists at the time found herself appalled by the coverage of the violence, and like the Black journalists that covered the Watts Riots in 1965, it also offered great opportunity for them.

A generation of Black journalists entered mainstream newsrooms immediately after the outbreak of violence in American cities in the late 1960s, just as the era created a spark in scholarship about Black life, the most well known being Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s infamous and much debated The Negro Family: The Case for National Action , which many cited as an explanation for the violence. Similarly figures such as Cornel West, bell hooks, the late Manning Marable, Patricia J. Williams, Michael Eric Dyson, Anna Devere Smith and many others rose to national prominence in the aftermath of the LA Riots, largely playing the role of interpreters of an expanding racial chasm in the post-Civil Rights era, that no longer pivoted on a Black-White axis.

Yet the figures who provided the most credible witness to the week-long violence that occurred in Los Angeles and the underlying tensions that led to the explosion of violence, were often marginalized in its coverage. Hip-Hop culture and rap music, for more than a decade prior to the LA Riots, provided commentary on the on-the-ground tactics of law enforcement, the inconsistent application of criminal justice in Black communities and the realties of poverty. Whether it was The Furious Five’s dissertation on such matters with “The Message” (1982), Toddy Tee’s “Batterram” (1985), which described the B-100 armored vehicle used by the LAPD to knock down the doors of suspected drug dealers, or NWA’s “Fuck the Police,” Hip-Hop offered a view into the kind of street level buy-and-bust strategies that accelerated the prison pipeline for Black males that inherently involved forms of police harassment, racial profiling and misconduct.

Many of those Black youth were clear about the linguistic slippages that gave the LAPD license to attack them. As Ice Cube told Angela Davis, “We're at a point when we can hear people like the L.A. police chief on TV saying we've got to have a war on gangs. I see a lot of black parents clap-ping and saying: Oh yes, we have to have a war on gangs. But when young men with baseball caps and T-shirts are considered gangs, what these parents are doing is clapping for a war against their children… That war against gangs is a war against our kids.” (Transition, 1992).

Ironically for many Black youth of that generation, the video tape of Rodney King’s beating, represented, perhaps, their last investment in the idea of American Democracy or at least the idea that there was justice. The violence that erupted on April 29th—too much of it unfocused, haphazard and detrimental to Black communities—was a product of a deep and compelling sense of betrayal.

The LA Riots became a ground-zero in the shift in the way that mainstream America covered race and how it framed the voices that would give witness to that reality. Hip-Hop’s political wing would not simply be demonized—Bill Clinton’s calculated political undressing of activist-turned-rapper Lisa Williamson (Sister Souljah) and the controversy surrounding Ice T’s “Cop Killa” being the most resonant examples—but the culture’s excesses were quickly transformed into the style du jour, creating a generation of Hip-Hop moguls, including Ice Cube, whose political rhetoric became increasingly measured and ultimately muted. The same could easily be said for the generation of Black Left intellectuals, who found themselves in regular rotation on The Charlie Rose Show and Talk of the Nation; few of us publicly defining ourselves as Radical Democrats—one of the favorite terms of the era—even if it is a politics that we are still deeply committed to.

The hand-held video camera that captured the beating of Rodney King, heralded the coming of a mobile culture, where the ability of citizens to capture the misconduct of law enforcement and other agents of the State is an everyday occurrence. Indeed the accessibility of such technology, in part, inspired B. Dolen’s recent collaboration “Film the Police,” which implores citizens to take hold of their own Democracy by shifting the frame to the State—a radical concept as the Obama White House considers whether to veto the Cyber Intelligence Sharing and Protection Act (CISPA), which was just passed in the House, and would give the government further means to provide surveillance of US citizens.

Rodney King may not have found justice that day that those four officers were acquitted in court; and folks of all races, who took to the streets in the aftermath of those acquittals, certainly did not find justice. In myriad ways, America is no closer to an honest understanding of how race functions in our society, than it was twenty-years ago; This despite the presence of a Black President, whose election has arguably dampened the political will to have such conversations. Yet the digital technology that was at the heart of our collective response to Rodney King’s beating, offered a view into how that technology could help shape future responses to such atrocities, whether they were captured on camera or not .

***

Mark Anthony Neal is the author of five books, including the forthcoming Looking for Leroy: (Il)Legible Black Masculinities (New York University Press) and host of the weekly webcast Left of Black . Neal is Professor of Black Popular Culture in the Department of African & African American Studies at Duke University.

Published on April 29, 2012 12:14

Can We All…Get It Right?: Remembering the LA Uprising

Can We All…Get It Right?: Remembering the LA Uprising by David J. Leonard | NewBlackMan

There are few days in life where you can say without a doubt, “I know what I was doing 20 years ago today.” This is the case today, on the 20th anniversary of the start of the Los Angeles Uprising.

Having dropped out of the University of Oregon after 2 quarters, I was living in Los Angeles working and taking two classes at UCLA. Like many middle-class white youth I presume, I paused when the verdict was delivered and noted the injustice that spurred my outrage before getting back to my life. I was angry, like many others, because a jury of THEIR peers concluded that 4 police officers did nothing wrong in beating Rodney King 56 times, but the anger lasted only for that second. That was the reaction from many in West Los Angeles. “That’s outrageous, can I get a cold beverage”; “what an injustice, is the mall open yet?”

I remember thinking little about the case after hearing the verdict,. I headed to work and then to my class at UCLA. Driving to my class, through the wealth of West Los Angeles, all was calm. Entering class, an introduction to sociology course that focused on inequality systemic racism and privileges, it was clear that the verdict changed little. Class was planned as usual. Yet, before long, with news reports of violence breaking out in South Central, Los Angeles, our professor announced the end of class out of concern for OUR safety. In a city immensely segregated, defined by systemic divisions that thwart interaction all while enacting violence on its residents of color, it is immensely telling that the Rodney King Verdicts/LA Uprisings became meaningful, if not visible, when people thought the riots were going to cross La Brea or other markers dividing the two LAs.

For the rest of that night and next day, I was paralyzed, watching television almost endlessly. In retrospect, for myself, and maybe others, the LA Uprising put a crack in the walls of segregation. Although living less than 15 minutes from South Central, Los Angeles, it might as well have been 10,000 miles away. That is the specter of segregation in Los Angeles. Even the media reporting then, and the ways that the verdicts and LA Uprising were being talked about demonstrated this fact as people continued to talk about what was happening “over there” concerned that it might “migrate here.” I was uncomfortable with the detached feeling paralyzing me so I decided to leave the state-protected bubble of West Los Angeles and I drove down to South Central on day 2 to donate some food, clothes, and stuffed animals to the First AME Church.

I was most certainly driven by my desire "to help," as I imagined what that meant twenty years ago, which most certainly reflected my white privileged understanding of privilege. Yet, I was also angered by the clear segregation of Los Angeles, not only in terms of geography, economics, and daily reality, but sentimentality and emotion.

The lack of sadness and anger within West Los Angeles was telling because the LA Uprising was not happening in our world; it was somewhere else, happening to someone who didn’t look like “us.” The power of race and class in eliciting not only empathy and connection, but also sentimentality and humanity, was on full-display in the days after the King Verdict. When I told people that I was heading down to South Central, they looked at me like I was crazy, as if I was driving into a foreign land amid a war. To them, it was a foreign land, one that they neither visited nor thought about except in moments of fear (“will the rioters come to the West Side) or heading to Lakers’ games. Despite voiced concerns about my driving just a few miles down the 10 Freeway, it was rather “uneventful” except in how this moment transformed me.

The drive forced me to reflect on my own assumptions and stereotypes, to think about why neighborhoods so close to my own were places I had never been (and thought of as so far away); it forced me to think about the violence and destruction that predated April 29th and bare witness to communities that West Los Angeles had abandoned; and finally, it forced me to reflect on the power of community, to see beyond the televisual representation of South Central Los Angeles rioting, to see families collecting food, kids playing, and people coming together. It forced me to look inward, to think about whiteness and privilege, to reflect on my stereotypes and assumptions. Even my ability to get my car and drive to South Central Los Angeles is evidence of privilege given the levels of state violence experienced by black and Latino youth entering LA’s white enclaves in West Los Angeles. What should have been a moment of introspection, of racial reconciliation and systemic change, instead became a moment, one that too many of us retreated as we are driving back to the “comfort” of a gated community.

Like me driving back to my middle-class world, much of Los Angeles quickly returned to its protected bubble and instead of focusing on self and policy, inequality and state violence, used the LA Uprising to justify persistent segregation I recall, for example, when teaching nursery school that summer, a child, upon seeing broken glass on the ground, told me “look what the black people did.” Although I did offer a critical intervention, I should have responded by saying “Actually, look what the white people did and while we are talking, remember the LA Uprising, the white people also did that.” ***

David J. Leonard is Associate Professor in the Department of Critical Culture, Gender and Race Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. He is the author of Screens Fade to Black: Contemporary African American Cinema and the just published After Artest: Race and the War on Hoop(SUNY Press). Leonard is a regular contributor to NewBlackMan and blogs @ No Tsuris.[image error]

Published on April 29, 2012 06:04

April 28, 2012

Malkia Cyril: Designing a New Rrradical Media

Malkia Cyril is the Founder and Executive Director of the Center for Media Justice (CMJ). As an award-winning organizer and communications leader, Malkia has more than 15 years experience conceiving and managing grassroots communications and media organizing initiatives. Since founding CMJ in 2002, Malkia has led the organization to help organizations like People Organized to Win Employment Rights, Media Literacy Project find communications strategies and policy solutions to support their campaigns for social justice change.[image error]

Published on April 28, 2012 04:47

April 27, 2012

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.