Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 1002

May 5, 2012

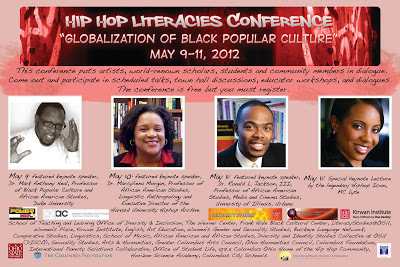

The 2012 Hiphop Literacies: The Globalization of Black Popular Culture at The Ohio State University

The 2012 Hiphop Literacies: The Globalization of Black Popular Culture

conference is designed to bring together scholars, educators, artists, students, and community members to explore Hiphop. The conference takes place May 9th-11th, 2012.

The 2012 Hiphop Literacies: The Globalization of Black Popular Culture

conference is designed to bring together scholars, educators, artists, students, and community members to explore Hiphop. The conference takes place May 9th-11th, 2012.Hiphop and Black popular culture are central to global youth culture. An artistic, social, and cultural movement, it is diverse and reflects the local histories, cultures and concerns of its worldwide practitioners, while adhering to Hiphop's ideological and aesthetic imperatives. Global Hiphop has emerged from the "collision and collusion between two powerful globally pervasive forces; transnational media and capital and African American popular culture that remains steeped in Africanist expressive modes." Hiphop is a powerful force, a "lingua franca for popular and political youth culture around the world." Its cultural codes, such as coming from something to nothing, being authentic, leaving one's mark on the world, having aspirations, having self-confidence, being relevant, and most of all being cool, are drawn upon to sell brands and have been used to "[re-write] the rules of the new economy." Brand marketing extraordinaire Steve Stoute has termed this global tanning, a state of mind, an attitude, a mental complexion. What tanning promotes both here and abroad all tangled up in Black popular culture is the "American dream," a myth that has helped to promote individualism, civic abandonment, inequality and maintenance of the status quo that has been assailed by Black political activists and other progressives for generations.

A major goal of "Hiphop Literacies" is to promote interdisciplinary research, teaching, and outreach around Hiphop, to stimulate ongoing dialogue and outreach across various disciplines in the academy and in the community. In addition to scheduled talks and workshops by renowned Hiphop scholars, artists and educators, the conference will host presentations and performances by scholars, students and community members. The conference will also feature a lecture and headline performance by MC Lyte.

Schedule of Events back to topDay One 9 a.m. - 12:00 p.m. Dr. Mark Anthony Neal, Professor of Black Popular Culture and African American Studies

Keynote & Town Hall (Wexner Film and TV Theater) 12:00 - 1:00 p.m. Lunch (on own) 1:00 - 2:30 p.m. Hiphop and the Caribbean Diaspora (Ramseyer 166)

Brazil and Japan (Arps 243) 2:30 - 4:00 p.m. Hiphop Practitioners (Arps 177) 4:00 - 5:30 p.m. Panel: Hawaii (Ramseyer 100)

Panel: Zimbabwe, Egypt and Kenya (Ramseyer 166) 5:30 - 6:30 p.m. Break for Dinner (on own) 6:30 - 8:30 p.m. Hiphop Art for the People: (Evans Lab 1008)

Speech is My Hammer: Hip Hop Art and the Reconstruction of African-‐Centered Cultural Semiosis, Dr. Samuel Livingston

DJing for the People, J. Rawls Day Two 9 - 10:15 a.m. Dr. Marcyliena Morgan, Professor of African and African American Studies, Harvard University, Executive Director of the Hiphop Archive

Keynote and Q&A (Wexner Film and TV Theater) 10:30 - 12:00 p.m. Featured Roundtable "Race, Theory and Gender in Hiphop's Global Future"

(Wexner Film and TV Theater) Drs. Treva Lindsey, James Braxton Peterson, Scott Heath and Ms. Regina Bradley 12:00 - 1:00 p.m. Lunch (on own) 1:00 - 2:30 p.m. Linguistics and Literacies (Arps 002)

Hiphop and Urban Education (Arps 200, Martha King Center) 2:30 - 4:00 p.m. Hiphop Pedagogies: Visual, Community and Youth Literacies (Arps 002) 4:00 - 5:30 p.m. Local Schools Panel/Community Town Hall (Wexner Film and TV Theater) 5:30 - 6:30 p.m. Break for Dinner/Reception for Educators, Students and Community Members (University Hall 014) 6:30 - 8:30 p.m. Workshop for Educators (University Hall 014)

Daniel Gray-Kontar Group and Yvonne Gilmore of Cornel West Theory Day Three 9 - 10:15 a.m. Dr. Ronald L. Jackson III, Professor, African American Studies, Media and Cinema Studies

Featured Workshop "Representations of Global Masculinity and Black Malehood"

(Wexner Film and TV Theater) 10:30 - 12:00 p.m. Sexualities and Feminisms (Ramseyer 200, Martha King Center)

Roundtable Social Movements and Socially Conscious Songs (Arps 386) 12:00 - 1:00 p.m. Lunch (on own) 1:00 - 2:30 p.m. Diasporic Experiences and Global Masculinities (Arps 002)

Cosmopolitanism, Exile, and Social Movement (Arps 012) 2:30 - 4:00 p.m. MC Lyte Keynote & Q&A (Wexner Film and TV Theater) 4:14 - 5:15 p.m. Reception and Poster Session (Ramseyer College Commons) 7:00 - 10:00 p.m. Concert featuring Special Hit Medley Performance by MC Lyte and Local Artists (Hitchcock Hall 131)

Published on May 05, 2012 06:13

Honoring W.E.B. Du Bois 2012

The Board of Trustees at the University of Pennsylvania appointed Dr. William Edward Burghardt Du Bois Honorary Emeritus Professor of Sociology and Africana Studies on February 17th 2012. The day included three intellectual panels, art installation, musical tribute, and a poetic tribute. This short video captures the day's activities.

With: Tukufu Zuberi, Lawrence Bobo, Camille Charles, Vivian Gadsden, Lewis Gordon, Stephanie Evans, Aldon Morris, Mary Pattillo, Reiland Rabaka, Gwendolyn Du Bois Shaw, Kenneth Shropshire, Quincy Stewart, Robert Vitalis, Howard Winant.

Published on May 05, 2012 04:47

May 4, 2012

Beastie Boys: "So What Cha Want" (RIP MCA)

Music video by The Beastie Boys performing So What Cha Want. (C) Capitol Records, LLC

Published on May 04, 2012 20:52

"They Can't Just Kill Us": Kenneth Chamberlain's Neighbors Speak Out as Police Avoid Charges

DemocracyNow.org

We get reaction from residents of the White Plains public housing complex, where Kenneth Chamberlain Sr. lived, to the news that the police officers who killed him in his own apartment will not be indicted. In the early hours of November 19, 2011, officers tasered Chamberlain and then shot him after they were called to his house when he mistakenly set off his LifeAid medical alert pendant. "Those cops that did this were wrong," says neighbor Denis Grant. "[They] need to be accountable for what [they] did ... You cannot kill us like this -- white, black, whoever. You can't kill us and get away with it."

Published on May 04, 2012 18:38

On His Way to Harlem: The Whimsical Soul of Gregory Porter

On His Way to Harlem: The Whimsical Soul of Gregory Porter by Mark Anthony Neal | NewBlackMan

With signature Kangol with ear flaps pulled over his head—looking more the vagabond than the genius—Gregory Porter would have cut a figure in any era; but it is his voice—as original as they come—that surely arrests everyone’s attention. Gregory Porter is among a generation of Black male jazz singers, including Jose James and Dwight Trible, who have made the choice against all logics to close ranks around a tradition that is so far removed from the Hip-Hop generation that there’s not a rearview mirror to consult. Whereas both James, who covered Freestyle Fellowship’s “Park Bench People” on his debut Dreamer and Trible have managed to dance on the fringes of hip-hop style production, Porter, save a few remixes, keeps it straight. As John Murph writes in a recent profile of Porter in Jazz Times , “There’s a very popular and profitable space where the theater intersects with true-blue jazz singing, but Gregory Porter ops for the latter. He’s the real deal.”

The career arcs the of Jon Lucien and Gil Scott-Heron in the 1970s are also instructive—neither would dare simply refer to themselves as jazz singers, though both were clearly indebted to that tradition. When Bobby McFerrin released his eponymous debut in 1982, covering Smokey Robinson, Van Morrison, Wayne Shorter, and quickly shifted to Jazz’s version of Biz Markie—his great gift to the tradition being “Don’t Worry Be Happy” (Chuck D: “…was a number one jam, damn if I say it, you can smack me right here”—it was clear that jazz singing was largely a dead form to young Black male singers; Will Downing was going to be an R&B singer or worse, a Smooth Jazz vocalist. Anyone remember Kevin Mahogany?

Born and raised in Bakersfield, CA, Porter and his seven siblings were reared by their mother, who was a former COGIC evangelist. It was Porter’s mother Ruth who encouraged him to pursue singing as an art, though he also entertained a career as an athlete, playing linebacker at San Diego State, before an injury ended his career. As he told Murph recently, his mother “creeps up in a lot of places in my art, whether I want her here or not.” The reverence that Porter holds for his mother, and women in general, shows up in subtle and not so subtle way in his music. The more obvious reference is the track “Mother’s Song,” from Porter’s new release Be Good. Less obvious are Porter’s covers of Nina Simone’s “Feeling Good” (from 2010’s Water) and Billie Holiday’s “God Bless the Child,” (from Be Good) both of which he does as unadorned a cappella performances.

Porter’s stellar debut, Water (2010), earned him a Grammy nomination, though it made him no more visible to Black music audiences and radio programmers. Like so many American jazz artists, Porter has had to cultivate his audiences abroad, giving even more credence to that vagabond look he has crafted for himself: have song, will travel. Porter is appreciative of his European and Asian audiences, telling Murph, “I’m not going over there aping some fake shit; they sense the authenticity…they tell you who you are in a way. The shame is that not enough American audiences—Black audiences—even know who Porter is, let alone, have heard Water.

While Porter’s covers of “Skylark” and “But Beautiful” are simply breathtaking, charting the same classic territory Jose James visited on For All We Know, released the same year as Water, it is Porter’s originals that truly standout. Tracks like “Illusion” and the title track “Water” recall the sparse ballads of Bill Withers during his +’Justments (1974) and Making Music (1975) period. Yet, Porter is not afraid to come hard, as he does on the insurgent “1960 What?” which speaks back to a broad tradition within Black music of naming evil in the world.

In the midst of the racist and systematic violence of so-called post-Race America, Porter defiantly sing “Young man coming out of a liquor store • With three pieces of black licorice in his hand y’all • Mister police man thought it was a gun • Though he was the one • Shot him down y’all • That ain’t right, ” the title of the song a reminder that what was once, is still. The power of the song has been captured in the remixes of the song, like Peter “Opolopo” Major’s “Kick & Bass Rurub” of the track. As Porter told writer Siddhartha Miller in Water’s liner notes, “It’s an album of love and protest.”

The Gregory Porter that appears on Be Good, released in February on the indie, Harlem based Motéma Music label, is one who is more polished. Besides his rousing cover of Nat Adderley’s “Work Song,” there are several signature ballads, including the lead single “Be Good (Lion’s Song).” The song perfectly captures the sense of whimsy that pervades Porter’s music—a quality that filmmaker Pierre Bennu placed front and center in his video treatment of the song, which conjures the “color” scenes from Spike Lee’s She’s Gotta Have It (1986). “Real Good Hands” (with nods the Duke Ellington’s “Heritage”) is another standout, as the groom-to-be engages the quaint tradition of asking his bride-to-be’s parents for permission to marry their daughter. Porter’s constant refrain of “I’m a real good man,” speaks volumes about his own negotiations within a marketplace has long forgot the value of regular folk. Even with that headgear, Porter’s is just a hardworking, regular dude, trying to do the right thing.

The centerpiece of Be Good is the rollicking tribute to Harlem on the track “On My Way to Harlem.” Packed with a celebratory nostalgia (“you can’t keep me away from where I was born • I was baptized by my daddy’s horn”), a sense of loss (“I found out through my way to Harlem • Ellington he don’t live ‘round here, he moved away, so they say”) and hope (I sure could use • some of those Blues • from Langston Hughes”), the song is a tour de force—one that Misters Baisden and Joyner, would do well to introduce their audiences to. I’m sure Frankie Crocker would have loved it.

Porter’s emergence points to the troubling dynamic of contemporary Black art: as musical artists like Porter, THEESatisfaction, Santigold and The Robert Glaspar Experiment represent a relative renaissance in Black music—hand-in-hand with the new media platforms birthed in the broadband era—mainstream media has turned a dead-era and blind-eye to it. If not for the availability of Porter’s “Be Good (Lion’s Song)” or “Illusion” on sites like Youtube, even fewer folks would know of his art.

Gregory Porter is on his way to Harlem, and we all should take his cue, and follow him there.

***

Mark Anthony Neal is the author of five books including the forthcoming Looking For Leroy: (Il)Legible Black Masculinities (New York University Press). He is professor of Black Popular Culture in the Department of African & African-American Studies at Duke University and the host of the Weekly Webcast Left of Black. Follow him on Twitter @NewBlackMan.

Published on May 04, 2012 10:16

May 3, 2012

Michael Kiwanuka: "I'll Get Along"

Michael Kiwanuka's new single 'I'll Get Along' taken from the debut album Home Again.

Published on May 03, 2012 18:52

Ruthie Wilson Gilmore: ""May Day is a day in which we rise up and say, 'We should be free,'"

DemocracyNow.org

In New York City's Madison Square Park, hundreds of people attended a "Free University" hosted by Occupy Wall Street, where professors gave free classes to May Day protesters. Activists said the event marked an alternative means of sharing knowledge outside the capitalist system. "This movement is all about building community and sharing and coming up with alternatives to the economic system that is so pervasive in our lives and in everything that we do," said Amin Husain, a key facilitator for the Occupy movement, who attended the event. "These are cracks in capitalism where we can actually give and take on our terms," he added. Ruthie Wilson Gilmore, a professor and co-founder of the prison abolitionist group Critical Resistance, brought her class from the City University of New York to the action. "May Day is a day in which we rise up and say, 'We should be free,' which means we should control the means of production so that we can have all the say possible in how we reproduce ourselves," said Gilmore. "Studying policing and studying capitalism and studying racism is a way toward figuring out how to change the future." Democracy Now! also spoke with poet Eileen Myles and professor and labor activist Jackie DiSalvo.

Published on May 03, 2012 16:43

From The Digital Crate—The Last Soul Brother: James Brown

From The Digital Crate—The Last Soul Brother: James Brown by Mark Anthony Neal | NewBlackMan

James Brown was of a generation of black men—mythological in many ways—who helped define the contours of freedom and possibility for black folk in the 20th century. They were the generation of “Soul Brothers”. Born shortly before and during the decade of the Great Depression, these men came to adulthood after World War II and had little choice than to be swept up in the whirlwinds of anticommunism and the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement. There was little question that these men were patriots—and in the best sense of the word—as they held American Democracy to the same standard at home and that it championed abroad. If Sam Cooke, shot dead before his prime, was the metaphor of possibility for this generation of black men, and Martin Luther King, Jr. and El Hajj Malik El Shabazz (Malcolm X), shot dead in their prime, were the very emblem of those possibilities fully realized, than James Brown was the bittersweet reminder that the men behind the mythologies rarely age with the grace that their iconography affords them.

As Soul Brother #1, the secular power of James Brown was palpable in every way to that of the King who was assassinated in Memphis and emboldened even more so after the King’s demise. It was Brown, remember, who was called to duty, as rioters were poised to tear the city of Boston to shreds in the days after Martin Luther King, Jr.‘s murder. “Say It Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud”—equally ripe for the discourses of Black Power and marketplace integration—resonated more powerfully than “We Shall Overcame” ever would for the watchful eyes of that soon to be post-Civil Rights Generation. But the humanity of the man—with its funky and messy flaws and frailties—could never sustain the myth, so much so that the image of the man who gave Black Power its soundtrack became a harsh reminder of its fractured legacy. And perhaps that’s the way it should be.

Born in Barnwell, South Carolina, in 1933 and raised in Augusta, Georgia, Brown epitomized the financial and political struggles of poor southern blacks in between the two World Wars. Brown’s arrest for armed robbery in 1948 turned fortuitous, as it led him to a lifelong friendship with Bobby Byrd. Their relationship would eventually lead to the founding of the Famous Flames, the band that would be the springboard for Brown’s early success. What made Brown appealing to so many was that he never forgot those youthful days in Augusta or those early struggles on the “Chitlin’ Circuit”, even as he ascended to the status of the “Godfather of Soul” in the mid-‘60s. James Brown was the “every man” counterpart to Aretha Franklin’s “round-the way-girl”—both as real as the wife beater, alcoholic, drug addict, unwed mother, and musical genius who was bound to live in any neighborhood in a still hyper-segregated Black America.

What also endeared Brown to his fans was his tremendous work ethic. Brown wasn’t called the “hardest working man” in show business for nothing, but that description extended far beyond the buckets of sweat that he produced after another one of his three-hour concerts. Like Duke Ellington did for the music in the decades before him, Brown was a torchbearer, taking the music directly to the people, sometimes 300 nights out of the year. In this regard, for nearly two-decades from the mid-‘50s until the mid-‘70s, Brown was the very epitome of the “Chitlin’ Circuit”, that legendary network of often black-owned clubs, dancehalls, bars, theaters, restaurants, and hotels that helped sustain black musicians, entertainers, and vendors during Jim Crow segregation. Indeed, the “Chitlin Circuit” helped Brown refine his own business model, seeing the value of a “Chitlin Circuit” gem like the Apollo Theater in Harlem, when he self-financed the live recording that jettisoned him to national visibility in 1962. Brown’s business successes aside, what was obviously at stake was the music itself, and Brown’s commitment to staying on the road was as much about economic self-preservation as it was about keeping the music in touch with the folk who needed it most—those everyday black folk for which a good party and some good food on a Saturday night were vital to their spirits as they prepared to hit the grind again on Monday morning, or, in some cases, hours after they left the club.

That musical innovation could occur during studio sessions betwixt those sweaty nights on the dancefloor was simply a marvelous by-product. When Brown’s 1967 classic “Cold Sweat” laid the groundwork for a new rhythmic paradigm in black popular music (creating “Funk” in the process), it was the consequence of all of those nights on the road. One could argue that with “Cold Sweat” and later tracks like “Say it Loud (I’m Black and I’m Proud)” and “Sex Machine” that a black artist had never been as in sync with the black public as James Brown was in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. In his book Funk: The Music, The People and the Rhythm of the One (St. Martin’s, 1995), Rickey Vincent makes the point that Brown “figured out how to orchestrate a drum set, and make everything in the band work around a groove, rather than a melody.” (73) Scholar and musician Guthrie Ramsey, Jr. agrees, adding in his book Race Music: Black Cultures from Be-Bop to Hip-Hop (University of California Press, 2003), that “Funk or the ‘in the pocket groove’ rivals in importance the conventions of bebop’s complex and perhaps more open-ended rhythmic approaches. Each imperative—the calculated freedomof modern-jazz rhythm sections and the spontaneity-within-the-pocket funk approach—represents one of the most influential musical designs to appear in 20th century American culture.” (154)

The kind of musical spontaneity that Ramsey describes was demanded by black audiences of the era; the music was expected to reflect the very improvisational instincts that they employed in their everyday lives. Though a track like “Say it Loud” may have been composed by Brown and longtime band member Alfred “Pee Wee” Ellis, one could credibly argue that it was a song written “by the people”, because it was so much “for the people”. While no one should mistake the powerful cultural politics of James Brown with real political action, Brown was able to translate his visibility in the late ‘60s into some semblance of access to the power elite in the United States. Much has been made of Brown’s relationship to and political support of Richard Nixon (the man who created the political climate in which black political organizations of the era could be dismantled and ultimately destroyed), but in Brown’s defense, he was swayed less by political ideology as he was the realities of opportunity. Brown’s politics throughout his adulthood are best represented by the track “I Don’t Want Nobody to Give Nothing (Open Up the Door, I’ll Get It Myself)”. For Brown, Nixon’s lip-service to “Black Capitalism” was simply more useful than the promise of a fortified welfare state or the threat of revolutionary violence. Ironically, Brown’s sharpest critique during the Black Power Era was aimed at soap-box revolutionaries in his song “Talking Loud and Saying Nothing”.

And once again, Brown’s political beliefs extended to his vision for the music. By the ‘70s, Brown used his considerable influence to create artistic opportunities for other artists including Hank Ballard (an early influence on Brown) and members of his own musical camp, such as Bobby Byrd, Lyn Collins, his backing band the JBs, which included Fred Wesley, Jr., Bootsy Collins, Maceo Parker among others, and Vicki Anderson, whose “The Message from the Soul Sisters” is arguably funk’s first feminist track. Like Brown’s recordings, many of these James Brown productions would be recovered a generation later by hip-hop artists. “The Message from the Soul Sisters”, for example, later formed the foundation of Lil Kim’s breakthrough track “No Time” (1997). Many in the Hip-Hop Generation were introduced to Bobby Byrd when Eric B and Rakim remade his “I Know You Got Soul” in 1986. And, of course, Lyn Collin’s “Think (About It)”, with the refrain “it takes two”, was the inspiration for Rob Base and DJ EZ Rock’s early hip-hop anthem “It Takes Two” (“Think” is also liberally sampled on Janet Jackson’s “Alright” from 1989’s Rhythm Nation).

In the mid-‘70s, as the denizens of the burgeoning R&B Nation of black middle class tastemakers began to distance themselves from the decidedly down-home flavor of Brown’s music, it was the embryonic Hip-Hop Nation that would provide a lasting legacy for Brown’s music. With hip-hop’s early emphasis on extended break-beats, Brown’s rhythmic innovations appealed to hip-hop DJs in the ‘70s. In his tribute to Brown, longtime journalist Davey D recalls that “back in the days when Hip Hop was first evolving in the ‘70s, Hip Hop’s pioneering figures routinely paid tribute to the musical offerings of [Brown]. While Black radio stations moved in a direction that embraced formalized disco, the musical landscape of the early Hip Hop Park Jams was juxtaposed. Classic songs like ‘Soul Power’, ‘Pass the Peas’, ‘Funky Drummer’ and ‘Get Up, Get Into It’, and ‘Get Involved’ would blare through the sound systems of Hip Hop’s early deejays and drive the early b-boys and b-girls to the edge.” Brown’s relationship with the hip-hop industry was mixed—for every “Unity” recording with Afrika Bambaataa, there were legitimate complaints about the unauthorized use of his music.

In the early days of the 21st century, hip-hop is simply the most visible example of James Brown’s influence. Sadly, the image of a torn and tattered Brown, taken shortly after a recent arrest for domestic violence, seems more in line with the sexist and misogynistic imagery that circulates in so much of commercial hip-hop. But James Brown’s real legacy can be found in the standard bearers of ‘80s black celebrity pop—figures like Michael Jackson, Prince, Eddie Murphy (“hot tub!”), Bobby Brown, and Tina Turner, who helped define the very notion of black crossover success two decades after Freedom Summer. James Brown never made it to that promised land, but as Soul Brother #1 goes, he can rest assured that as his tribe steps forward into the future, they will continue to do so on “the good foot.”

***

Originally Published at Popmatters.com

Published on May 03, 2012 07:01

National Black Justice Coalition: "Scales of Justice Tilt In Favor of Robert Champion Jr."

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Kimberley McLeod

Email: kmcleod@nbjc.org

Phone: 202-319-1552 x 102

Scales of Justice Tilt In Favor of Robert Champion Jr.

Thirteen people charged in hazing death of a gay drum major

Washington, D.C. - May 2, 2012 - This afternoon, prosecutors announced that eleven individuals have been charged with hazing resulting in death, a third-degree felony, in the homicide of gay drum major, Robert Champion Jr. Two others will face misdemeanor charges. Last November, Champion, 26, was found unresponsive aboard a band bus after the school's biggest game of the year. Police ruled the death a homicide from hazing. Witnesses told the parents that Champion might have been hazed more severely because of his orientation. The National Black Justice Coalition (NBJC), the nation's leading Black LGBT civil rights organization, was at the forefront urging the U.S. Department of Justice's Office for Civil Rights (OCR) and Community Relations Service (CRS) to launch an investigation into Champion's death as a potential anti-gay hate crime.

"What could possibly drive someone to pummel another human being to death?" asks Sharon Lettman-Hicks, NBJC Executive Director and CEO. "It was absolutely heart-wrenching to listen to State Attorney Lawson Lamar detail the brutal beating that killed this young man.""There were thirty witnesses on that bus and it took six months to even tilt the scales of justice in Robert Champion Jr.'s favor," continues Lettman-Hicks. "The sad reality is that justice drags its feet when a Black life is at stake. There's even less outcry when it is the life of someone Black and gay. That is why we must continue to proactively advocate on behalf of Black LGBT people who are victims of violent crimes." The National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs has found that violence against LGBT people is up 23 percent, with people of color as the most likely targets. Of the victims murdered in 2010, 70 percent were people of color.

In addition to launching a petition to demand justice for Champion, NBJC has partnered with the Department of Justice's Community Relations Service to host a Hate Crimes Prevention Act Forum at FAMU. The forum will include students, administration, faculty and staff, representatives from state and local LGBT advocacy organizations as well as local, state and federal law enforcement (including campus police) to provide a better understanding of the federal hate crimes law. Although this case was not ruled a federal hate crime, prevention education is needed more than ever to avoid the senseless and violent loss of another life.

"This is just the beginning," adds Lettman-Hicks. "Law enforcement alone will not address the systematic and societal realities around violence in our community. There are minimal, if any, policies or support structures for LGBT people within the 105 HBCUs around the country."

"These institutions develop many of our future leaders but fail to create safe and nurturing environments for all of our young people to thrive. Combined with legal protections, cultural shifts on these campuses are needed to literally save lives. Our work doesn't end here."

Black LGBT people are at the intersection of laws like the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act. That is why NBJC will be leading a discussion with the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the Department of Justice to discuss prevention of hate crimes targeted at the LGBT population at HBCUs, and to identify opportunities to effectively address and respond to these incidents in a collaborative manner.

NBJC strives to foster honest and intentional dialogue within African American communities addressing the challenges of the Black LGBT community. Be it hazing, harassment or hate crime, justice must be served.

# # #

The National Black Justice Coalition (NBJC) is a civil rights organization dedicated to empowering Black lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people. NBJC's mission is to end racism and homophobia.

Published on May 03, 2012 05:58

May 2, 2012

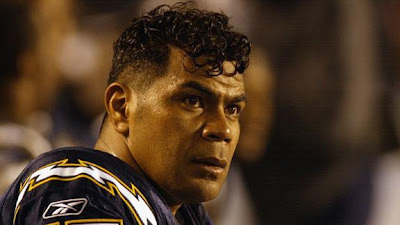

The NFL or The Hunger Games? Some Thoughts on the Death of Junior Seau

The NFL or The Hunger Games? Some Thoughts on the Death of Junior Seauby David J. Leonard | NewBlackMan

Last weekend I saw The Hunger Games. When I walked into the theater, I could not have told you one thing about the film, and if not for the uber publicity, I likely would have thought it was a show on the Food Network. While there is much to say about the film, I was left thinking about how it merely recycled the common Hollywood Gladiator trope. Mirroring films like The Running Man and The Gladiator, The Hunger Games highlights the ways that elite members of society make sport and find pleasure out of the pain and suffering of others. That is, they find arousal and visceral excitement in watching people battle until death. Within such a narrative trope is always a class (and at times racial) dimension where those with power and wealth (the tenets of civilization?) enjoy the spectacle of those literally and symbolically beneath them fighting until death. The cinematic representation of the panopticon, whether within the past or in futuristic terms, allows for commentary about the lack of civility, morals, and respect for humanity amongst the elite outside of our present reality. As these morality tales take place in the past (and or future), they exists a commentary about our present condition, statements about how far we have evolved and/or the danger of the future.

Yet, what about The Hunger Games in our midst? What about the NFL, a billionaire enterprise that profits off the brutality, physical degradation, and pain of other people? What about a sport that celebrates the spectacle of violence? Unlike The Hunger Games or Gladiator, films that depict a world where people bear witness to death, hungrily waiting the next kill, football and hockey fans sit on the edge of their seat waiting for the knock out hit, the fight, and bone crushing collision. The game doesn’t end with death but death results from the game. Out of sight, out of mind, yet our hunger for games that kill are no different.

These are issues NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell and the various team owners are loathe to discuss, but with Seau, they won’t have a choice. In Seau, a larger than life Hall of Fame player, we have someone with friends throughout the ranks of the league and especially in the media. It will be incredibly difficult to keep this under wraps. People will want answers. Over the summer, former Chicago Bears safety Dave Duerson took his own life with a gunshot to the chest so his brain could be studied for the effects of concussive injuries. Junior Seau now joins him, a gunshot to the chest. There is a discussion that the NFL is going to have to have with a team of doctors, players and the public. Right now, this is not a league safe for human involvement. I have no idea how to make it safer. But I do know that the status quo is absolutely unacceptable.

Lester Spence also pushes us to think about suicide as a potential consequence of NFL/NHL careers.

The first thing we should do is think about Wade Belak, Rick Rypien, and Derek Boogaard. They were three NHL enforcers (people who made their hockey careers through their fists rather than through their sticks), who committed suicide over the past year. Each of them had a history of concussions. Boogaard made the courageous decision to offer up his brain to science. The results suggest his suicide may have been the result of brain damage.

It is only after thinking about Belak, Rypien, and Boogaard, that we have the medical context to understand Seau. Not so much to understand why he committed suicide–if there were a simple relationship between concussions and suicides the suicide rate of former NFL/NHL players would be far higher than it is. BUT to understand how his suicide may be at least a partial function of his NFL career. It is hard not to think about the consequences of sporting violence. It is hard to deny the implications here when NFL players commit suicide at a rate six times the national average; it is hard not to think about a rotten system when 65 percent of NFL players retire with permanent and debilitating injuries. It is hard not to think of the NFL and NHL as a modern-day gladiator ring where our out-of-sight childhood heroes are dying because of the game, because of sport, because we cheered and celebrated brutality and violence. It is hard not to think of the NFL as nothing more than the real-life hunger games, our version of death as sport, when we look at reports following suicide of Dave Duerson:

This intent, strongly implied by text messages Duerson sent to family members soon before his death, has injected a new degree of fear in the minds of many football players and their families, according to interviews with them Sunday. To this point, the roughly 20 N.F.L.veterans found to have chronic traumatic encephalopathy — several of whom committed suicide — died unaware of the disease clawing at their brains, how the protein deposits and damaged neurons contributed to their condition.

How much data do we need; how much proof; how many suicides, how many twenty-something football stars need to die with chronic traumatic encephalopathy before we see a problem; how many ex-players need to die, only to find out that football had left their brain “consistent with that of an 85-year-old man” until we demand change? How many more deaths before we realize that the hunger games aren’t in the future but it is are our current national pastime. How many families need to lose a father and brother, son and husband, before we stand-up and walk away because death should never be sport. That seems to be the message of The Hunger Games; one can only hope we can catch up to the future.

***

David J. Leonard is Associate Professor in the Department of Critical Culture, Gender and Race Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. He has written on sport, video games, film, and social movements, appearing in both popular and academic mediums. His work explores the political economy of popular culture, examining the interplay between racism, state violence, and popular representations through contextual, textual, and subtextual analysis. Leonard’s latest book After Artest: Race and the Assault on Blackness was just published.

Published on May 02, 2012 20:34

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.