Sarah Airriess's Blog, page 5

February 8, 2020

Sea Ice: The Basics

Antarctica is, as we all know, a continent of ice. But the ice isn’t just the ice caps and glaciers on the continent itself – it extends off the coast in all directions as the Southern Ocean seasonally freezes over. This fringe of frozen sea gives the penguins a place to escape their predators and the seals a safe place to raise their young; it shelters a number of fascinating ecosystems in the fertile waters beneath it; it offers a platform from which scientists can study their submarine subjects more or less directly.

It also provides a very convenient way of getting to places which would be cut off by water otherwise, but before one can travel on the sea ice, one needs to understand it. The practical skills of sea ice safety are predicated on an understanding of how the natural system works.

Sea ice forms when the air temperature drops below -2°C/28.4°F, the freezing point of salt water. Obviously Antarctica gets well below that in the winter, so the sea ice spreads over much of the surrounding ocean and freezes to a substantial depth. There are other forces acting upon the ice than temperature: currents, wind, storms, and the activities of humans and animals can break it up, and it often breaks up a few times before finally freezing solid for the winter. (The winter before I arrived was particularly bad for sea ice formation, which resulted in much wariness about its condition come summer, and significantly impacted some regular operations.)

When summer comes, and the air and water warm up again, the sea ice gradually decreases and weakens to the point where it breaks up and heads out to sea, returning open water to the shores of McMurdo Sound and starting the cycle over again. How much of the ocean freezes, and how much of that frozen ice breaks away the following summer, fluctuates year on year.

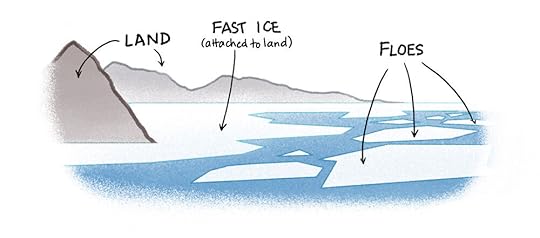

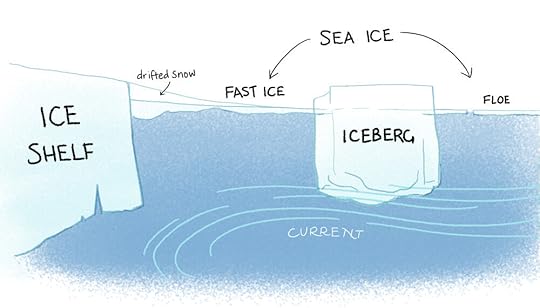

The ice attached to the solid rock of the shore, or to the face of an ice shelf, is called ‘fast ice’ (think of the phrase ‘hold fast’ rather than an indication of speed). When it breaks up and floats freely on the ocean, that’s a floe.

The floes drift out to sea and join the pack ice, a belt of broken-up seasonal ice and icebergs that rings the continent before gradually melting into the warmer ocean further north.

From sea level, it’s hard to tell what’s happening with the ice more than a mile or so away, but sometimes the sky gives you a clue. Just as water and ice reflect what’s around them, clouds do too, albeit in a more diffuse way. A cloud over open water will look significantly darker than one over ice, because ice is white and open water nearly black. In illustration form, from a high vantage point, it looks like this:

In the real world, this is what a water sky looks like from the vantage point you’re most likely to see it. In this case it’s reflecting the open water at Cape Royds, 20 miles away!

Throughout the summer, the edge of the ice eats closer and closer to land, accelerating as the ocean and air warm up. Often the ice reaches a tipping point and the last of it goes out in a rush. Last year it went out all the way to the ice shelf, which it does not often do, in just a few days. Luckily someone caught it on video:

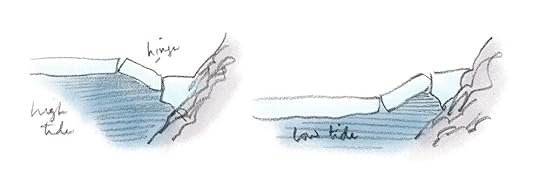

So: the sea ice, as the name suggests, rests on the surface of the sea. But the sea is not a static thing! The tides raise and lower it twice a day. The sea ice is not a rigid lid; it neither suppresses the tides nor rises uniformly with them, but breathes almost like a skin, thanks to the mechanics of the tide crack.

A strip of ice stays firmly attached to the land – this is the ‘ice foot.’ The constant flexing of the ice in response to the changing water levels makes a permanent crack some distance out from the land. There is a little more ice, then another crack, or two, and these joints allow the ice to rise and fall with the tide. Here is a time lapse of that exact thing happening:

Seals love the tide crack because it affords them a dependable breathing hole and often a means by which to climb out onto the surface of the ice. Wherever you see seals you know there will be a crack somewhere nearby. These seals appear to be enjoying the tide crack around Glacier Tongue, looking across McMurdo Sound by way of Tent Island.

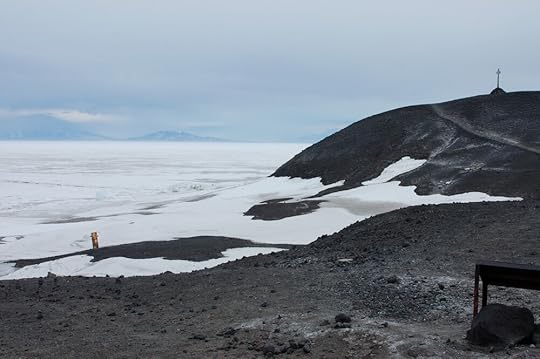

We visited a tide crack closer to home on my sea ice training: this one is at the foot of Arrival Heights. As you can tell, it is low tide. The great boulders of ice on the slope had been thrown up in one of the winter’s storms, which will give you an idea why the ice took so long to form.

There is a LOT more ice on Antarctica than just the seasonal ice, however. Most of the permanent ice is in the polar ice cap, miles thick in places, which slowly flows down to the coast in great glaciers. In some cases these spread out over the surface of the sea, forming an ice sheet. The Ross Ice Sheet, for example, is the size of France and over a thousand feet thick on average. It is floating on water – which, as it is liquid, is above -2°C* – so the nearer it gets to the open ocean the more it melts away, though it is always exponentially thicker than the sea ice. As this great sheet of ice is subjected to warmth and weather, it grows unstable, and bits of it break off and float away. These are the icebergs. Every ice sheet in Antarctica produces icebergs, as do most of the glaciers: the important thing is that icebergs are not frozen ocean water but chunks of the polar ice cap that have broken off into the sea.

Because icebergs are so much more massive than the sea ice, their lower reaches can be subject to deeper ocean currents. These can move them around quite independently of the sea ice, which is powerless against such a monster even if it appears to be frozen solidly in. Icebergs have been seen ploughing their way through pack ice that would stop a ship.

At the boundary between the sea ice and the ice shelf, the constantly blowing southerly winds have deposited a snowdrift, so from the surface, it looks like one gradual slope, and you’d never guess you were climbing from thin ice maybe a few years old to a fixture of several centuries.

Now you know about sea ice! Next time I will teach you all about cracks and how not to fall into one, and then you will be all set to whizz over that thin skin of ice between you and the dark cold depths of the sea.

*There are conditions in which liquid water can be below -2°C, but for the sake of discussing sea ice generally, it is simpler to ignore the rare exceptions in the interest of clarity.

February 1, 2020

Arrival Heights

With the heavy schedule of trainings and breakfast meetings, I fought to get every ounce of sleep I could. Word on the street was that the light was much better for photography at ‘night’, when the sun was lower in the sky – the angle making the light warmer, and shadows longer and richer – but I was so exhausted by the end of the day that staying up till midnight just for the sake of some photos seemed rather foolish.

Then, one day, an afternoon’s plans got cancelled, so I took a nap instead, in order that I could go on a nighttime hike and see the midnight sun. There are a few trails near enough McMurdo that you are allowed to hike them alone, and one of these is a ridgeline trail up Arrival Heights. This was sure to afford some good photo opportunities, and was of historical interest as well. Arrival Heights was a good vantage point over McMurdo Sound, and the elevation affords a view of the sea ice between Hut Point and Cape Evans, so as you might imagine, the men were up there all the time while they were waiting to get back from the Depot Journey.

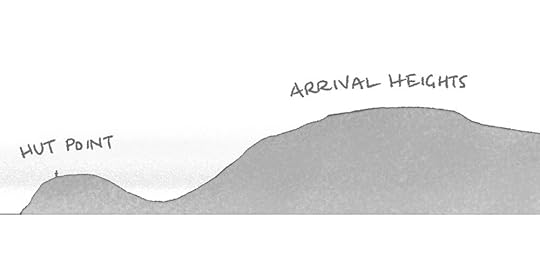

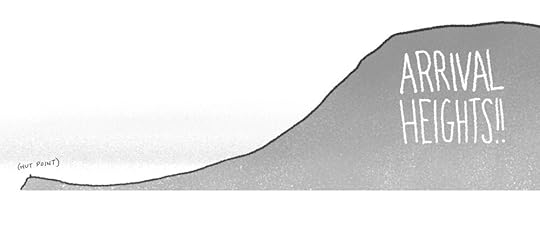

Arrival Heights was one of my biggest surprises. I had seen many photos of Hut Point, of course, and probably a few of Arrival Heights in passing, but I had never seen them (as far as I knew) in the same photo. If you had asked me to draw what I thought the profile of the peninsula looked like, having seen both features in isolation I would have guessed at this:

In reality – and I frequently found myself staring at this view, trying to comprehend my shattered expectations – it is more like this:

The trailhead is just behind the Discovery Hut. I was a little apprehensive about how my poor legs, atrophied by life on the Fens, were going to handle the great incline, but I would just have to find out. My more immediate concern was the skuas.

What an innocuous little bird, there, the sun glinting on ‘the symphony of brown and gold’ as Wilson described it. Now, it was very exciting to see skuas, especially the first few times, as it meant I was IN ANTARCTICA, but they are scary birds! I had read all about their piratical ways, of course, but my coordinator also told me of the time she was divebombed by one which was after her breakfast – ‘like being hit on the back of the head with a roast chicken.’ I had not been hit yet, but had been buzzed by a few low reconnaissance flights, close enough to see the malice in their eyes. They were, apparently, nesting, and though I hadn’t seen any evidence of chicks or even eggs yet, they were clearly feeling In A Family Way and defending their sites accordingly. A pair of them had set up house on the ridge near the Hut, and the trail looked like it was going to pass dangerously close. I escaped with my scalp this time, perhaps because I was quiet and alone and gave them due obeisance as I passed.

The next point of interest was a memorial to Richard Williams, a US Navy man who was hauling some of the supplies for the building of McMurdo across the sea ice when his tractor broke through and he drowned. The Chaplain at the time was Catholic (I don’t know about Mr. Williams) and happened to have a statue of Mary on hand (as you do), so erected a shrine which became known as Our Lady of the Snows.

Because of the improvised grotto, she has been nicknamed ‘Rollcage Mary.’ Some find this offensive, but I suspect the teenage mother and refugee whose firstborn son was lynched by occupying forces can probably take it in stride.

Onwards and upwards!

It’s not long before you start to get a high vantage on Hut Point. That’s Mt Discovery across the Sound, and Black Island poking its head above the thin strip of cloud. Out Lady of the Snows is at lower left. If you really look, you can see the low pyramid roof of the Discovery Hut halfway between the Hut Point promontory and the next bump of land.

Facing the other direction gives you a good demonstration of how, when they say Arrival Heights, they mean HEIGHTS. It’s one long, steep slope of igneous scree all the way to the tide crack at the bottom. The word ‘precipitous’ was at the front of my mind.

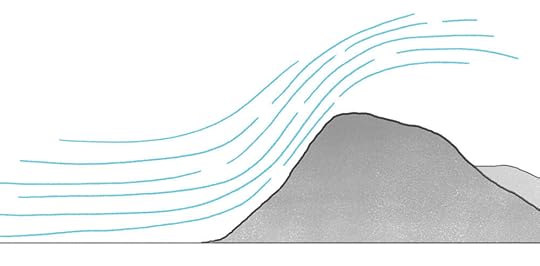

That night, there was a north wind – not very strong, but enough to make a big difference in one’s perception of temperature, depending on the degree to which one was sheltered. As expected, if I stood right on the ridgeline, I got the wind full in my face, but if I stepped back even a couple of feet, it was calm. This ended up being a very important discovery later, so I illustrate the principle for you here.

![[L] Standing on the ridgeline, in the wind. [R] Standing back from the ridgeline, out of the wind.](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1586659175i/29277877._SX540_.jpg)

[L] Standing on the ridgeline, in the wind. [R] Standing back from the ridgeline, out of the wind.

If you’ve ever driven in a convertible with the top down, it’s the same phenomenon by which the windscreen keeps air in the interior space of the car relatively still.

One sometimes gets the impression, around McMurdo, of being on Mars, but up here, away from the town, the impression gets much stronger. This radome can be seen all around the station, but without the context of town, it takes on a more extraterrestrial flavour.

Partly, the Martian impression is made by the exposed earth of the Hut Point Peninsula. Scientists are keen to remind us that there are all sorts of exciting microbes living in Antarctic soil, but it looks completely dead to the naked eye. What you can’t tell in the photo is that it’s also very loose: the trail here is packed, but if you were to come up here without it, you’d find it hard to get a foothold. Instead of the bedrock with a thin layer of loose pebbles and dust, as I’m used to from hiking in mountains, it feels like the whole hill is a dirt pile. The porous lava rock is light for its volume, and the continuous cycles of extreme cold and sun-warmed thaw keeps breaking it into smaller and smaller pieces, so it feels almost like walking on breakfast cereal.

Here is a closer look at some rock in the process of breaking into smaller rocks. I could have pulled it apart with my hands if I’d tried.

From up here, the view down to Hut Point not only reinforces how high Arrival Heights is, but how incredibly tiny and isolated the Discovery Hut would have been in a vast, incredibly vast, magnificently vast polar wilderness.

Officially, the trail loops up to the radome and then down the access road and through town, but this would have added a good deal of time without adding much interest. The scramble down was pretty quick, and I hardly had to do any of it on my bum. I got back down to the starting point just after midnight, so to prove a point about the 24-hour sunshine:

To be fully transparent, here, astronomical midnight was fifty minutes away – McMurdo functions on New Zealand time, which, being summer, was on Daylight Savings, so real midnight is at 01.00. But that was late enough for me, and I went to bed worthily exhausted and satisfied with a job well done.

January 25, 2020

Discovery Hut: Photo Tour

Now that you’re up on the history of the Discovery Hut, let’s take a stroll around it.

The entrance is on the southerly side, facing McMurdo Station. For its protection, the Antarctic Heritage Trust have fitted the door with a hefty padlock, but this is OK because you are with a Hut Guide who has the key, and will keep an eye on you during your visit to make sure you don’t pocket any artefacts.

The door is on the southwest corner of the hut, at one end of the three-sided verandah. In the Australian Outback, which this hut was intended for, it would provide a margin of shade and keep the walls of the structure cool. Here, it drifts up with snow, but if the building’s margin is kept clear, can provide some semi-sheltered outdoor storage space. This space was used to house the ponies and dogs when parties stopped here to or from more southerly destinations.

While your Hut Guide grapples with the lock, you notice that what looked like a pile of leather is a mummified half-butchered seal, which gives you an inkling of the realities of life in this environment, in the days before giant cargo ships brought tons of frozen food every year for your breakfast bacon and grapefruit juice.

The Guide has opened the door, and brought out the boot brush. You must thoroughly brush all the snow and volcanic gravel off your shoes before you enter. The hut is enough work to take care of without everyone tracking in moisture and grit. If you are very clever, you will remember to put your clean foot on the step while you brush the other one, and not back into the dirt.

You step into the darkness of the hut, and immediately notice that it smells like a barn. When your eyes adjust, you realise you are smelling the wind-eroded hay bales that have been stacked in the vestibule.

I don’t know for sure if this was the famous ‘compressed fodder’ but it’s all in very small bits, not long stalks of straw, and certainly looks compressed – more like chipboard than hay – so I’m going to guess it is.

You follow your guide into the main interior space of the hut, and briefly marvel at seeing it for the first time, before you are called over to the guest book to sign in. Your guide provides you with a pencil of her choosing, because she finds the ones supplied by the AHT to be too hard. To your amusement, you observe that the offending pencil is the same brand as the ones provided to fill out document request forms at the archives at SPRI.

Now that you have filled in your name, date, and time of entry, you can begin to explore the place properly. You are standing in the largest ‘room’ of the building, the wider arm of an L-shaped space which wraps around the improvised inner compartment. This was where the Terra Nova men slept on their way back from the Depot Journey, where their sleeping bags were turned into a ‘snipe marsh’ by the meltwater from the ceiling. For reasons lost to history, it was known as ‘Virtue Villa.’

There is a lot to see here, but your attention is first drawn upwards, because there is the famous ceiling cavity that was filled with ice! You have always had trouble picturing it, and it turns out to look nothing like you would have imagined.

It’s hard to tell in this photo, but the ceiling actually slopes upwards to the centre, just like the roof except a shallower pitch.

The fact that you can see into it at all is due to a remarkable but little-known event on the Terra Nova Expedition. When the main party were off making the big journey to the South Pole, four of the men left at base manhauled a load of extra food and fuel out to One Ton Depot, to restock it for returning parties. Their first night after leaving Cape Evans was, as usual, spent at Hut Point, but one of the men ‘had some feeling against sleeping in the Hut’ and persuaded the party to leave the supplies inside but sleep in a tent outside. During the night, a portion of the ceiling, still burdened by the unmelted ice above it, fell down – it would have killed the men, had they been sleeping there.

At the bottom of one of the roof support beams, you see a curious metal contrivance, and realise it must be a blubber lamp, mounted at just the right height for reading or journal writing in one’s sleeping bag on the floor. When burning, it would have added its lick of smoke to the general miasma which has stained the ceiling and curtain black.

Next to the blubber lamp is a crate with what look like ration bags – a grimier version of the ones you’ve seen in museums, anyway – and possibly a measuring bowl.

To your right, on what had been the far wall, is a case containing some food tins of a rather startling hue.

The orange spots are rust from the tin beneath. These contain barley, according to the label.

Now you can see down to the previously hidden corner. At the end is another window and, next to it, some curved wooden staves. They look like sledge runners, but the curve is the wrong shape. Your guide tells you they are tent poles, and you realise this must be one of the dome or bell tents that were mentioned in diaries but never photographed. It would have been far heftier than the dome tents you remember from camping as a kid, with the bendy metal poles that threaded through the fabric.

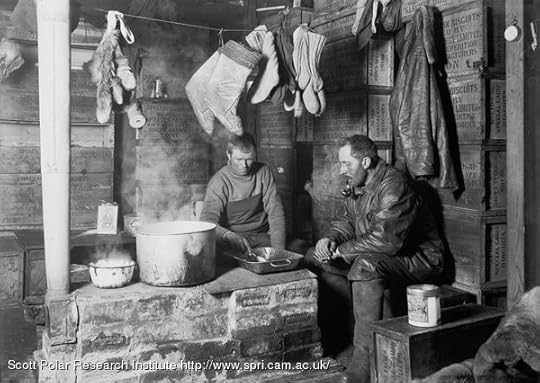

Now you are in more familiar territory, for in front of you (or behind you, if you are still looking at the tent poles) is the kitchen area, walled off from the rest of the hut by that heavy curtain, which had once been the winter awning of the Discovery. You remember this space from that photo of Dmitri and Meares which I shared last week, only now you are looking at it from the opposite angle, and it’s in colour and 3D.

Also, Meares and Dmitri are no longer here. Obviously.

Beyond the blubber stove is a platform raised on yet more biscuit cases, which would afford at least two men the luxury of sleeping off the cold floor. Above it – presumably to take advantage of the greater warmth of the kitchen – is strung a washing line, with a pair of thick woollen thermal underwear bottoms and a very rough-looking canvas trousers, probably one of the Ross Sea Party’s.

On the stove is a wide pan with a layer of some unidentifiable chips in it. It’s probably another relic of the Ross Sea Party, but it puts you in mind of one of Cherry’s stories from that jolly camping holiday in the hut while waiting for the sea ice to freeze.

"Who's going to cook?" was one of the last queries each night, and two men would volunteer. It is not great fun lighting an ordinary coal fire on a cold winter's morning, but lighting the blubber fire at Hut Point when the metal frosted your fingers and the frozen blubber had to be induced to drip was a far more arduous task. The water was converted from its icy state and, by that time, the stove was getting hot, in inverse proportion to your temper. Seal liver fry and cocoa with unlimited Discovery Cabin biscuits were the standard dish for breakfast, and when it was ready a sustained cry of 'hoosh' brought the sleepers from their bags, wiping reindeer hairs from their eyes. I think I was responsible for the greatest breakfast failure when I fried some biscuits and sardines (we only had one tin). Leaving the biscuits in the frying pan, the lid of a cooker, after taking it from the fire, they went on cooking and became as charcoal. This meal was known as 'the burnt-offering.'

Lighting the kitchen is a window with a frayed end of wire hanging in it. Was this what remained of the telephone wire which was laid over the sea ice between here and Cape Evans, providing communication between the two huts? This side of the hut does face Cape Evans, so it’s possible, but as far as you can tell, no trace of the telephone remains.

Reverse angle of the kitchen, as in the historic photo. The lighting is entirely natural, but you couldn’t ask for anything more atmospheric, or theatrical.

Past the laundry, you walk into another partitioned section of the hut. This area has a lower ceiling, and would have been under one of the outside awnings except that the wall has been pushed out to the edge of the roof, enclosing it. It is something like a pantry, with a large shelving unit between it and the kitchen, on which are arranged some choice artefacts. As you walk through, back to the first room, you pass a curious square column of bricks rising out of a hole in the floor. The Guide tells you this was the pedestal for a gravity-measuring pendulum, which needed to be in direct contact with the Earth.

Now we are back where we started, more or less, standing at the guest book. Before you sign out, your Guide implores you to go back into the vestibule and look into the other compartment. So you do; walking down towards the hay, you poke your head around the end of the partition and see what looks like a miniature abattoir.

The carcasses hanging on the wall have ungulate legs (out of shot in this photograph) which means they must be sheep, not seals. New Zealand was very keen to shower frozen mutton on departing expeditions, and this familiar taste of home was regarded as a treat by the travelling men who otherwise ate the local wildlife, much of which tasted of fish. In the corner is what looks like a headless, hollowed-out skin of an Emperor penguin. Two Adelie ribcages sit on the crate next to it. It would have made sense to store meat in this room as it certainly would have been very cold. Your Guide tells you that the door to your right was originally the main entrance; the door we have come in was regarded as the ‘back door’. The original front door is permanently shut, now, so the back door is the only way to come or go.

That’s it; you’ve now seen all the dark and secret corners of the Discovery Hut. You enter your departure time in the guestbook and clump back out the door. While the Guide sweeps the entryway and brings in the boot brush, you stand outside the door looking out over the Sound, trying to imagine what it would have been like to live here for months without any other sign of human habitation as far as you could see.

View to the south: L-R Observation Hill, White Island, Minna Bluff, and Black Island.

View to the west: L-R Mt Discovery (capped with cloud), Brown Peninsula, and in the middle ground, the Hut Point headland with Vince’s Cross on top of it.

From Vince’s Cross, you can look down on the descendants of the Weddell seals that sustained the early explorers, slumbering peacefully under the protection of the Antarctic Conservation Act.

Before long, you and your Guide are fighting the famous Hut Point wind to get back to base, where you will have apples, oranges, and fresh greens brought down by the cargo jet you rode in on. The seals around Hut Point are safe from the needs of the Galley and protected by international law; if you get peckish or miss dinner, there is hot pizza available all through the night. The Discovery Hut, and the Hut Point wind, haven’t changed much since the first explorers were here, but some things have, probably for the better.

January 18, 2020

The Story of the Discovery Hut

You may have noticed that last week I breezily mentioned a visit to Scott's Discovery Hut as though it were just another class on the schedule. It most definitely was not! Wandering around one of the principal locations of the Terra Nova Expedition – of the whole of Heroic Age Antarctic history – was the pinnacle of the sensory overload of my first 36 hours on the continent, not least because the grubby old Discovery Hut is one of the least well documented sites, so most of it was completely new to me. To visit the other locations on my itinerary, I needed one or another sets of training, but Hut Point is only a short walk from McMurdo Station on solid ground, so my coordinator was keen to get me there as soon as possible.

My first full day in Antarctica was the coldest of the whole trip. I noted in my journal that it was -4°F/-20°C – I don't recall if that was with wind chill or without, but it was definitely windy that day, so you can imagine. The previous day's flurries were still blowing around, so the atmosphere was properly polar, and for the first time I was glad I had brought the heavy-duty boots that had been such a boulder in my luggage.

Some members of Antarctica New Zealand visit Vince’s Cross (a memorial to seaman George Vince, who died nearby on the Discovery Expedition) at the promontory just down Hut Point from the Discovery Hut.

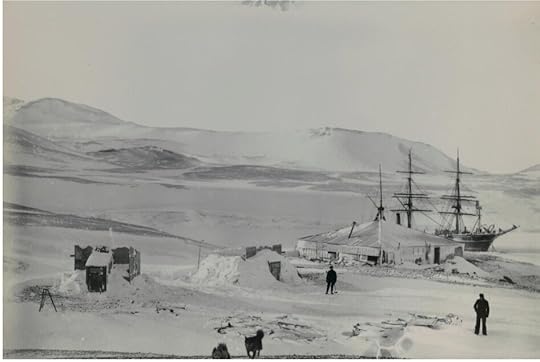

The Discovery Hut is named such because it was built on the Discovery Expedition, in early 1902 when the ship had found its permanent berth in the small bay at the end of the southernmost peninsula of Ross Island. The bay was imaginatively dubbed Winter Quarters Bay, and the spit of land adjacent to it was called Hut Point, the creativity of which was extended to the whole Hut Point Peninsula. The hut itself had been picked up in Australia, where it was a flat-pack prefab intended to be transported to the Outback and used to house cattlemen as they drove herds across the country. As such, it was designed to shed heat – not an ideal feature in an Antarctic dwelling, but it was never intended to be lived in, rather to serve as a warehouse and emergency shelter should anything happen to the ship. Subsequent expeditions used it more than the Discovery did, because of its proximity to the permanent ice of the Barrier, which made it a key staging point for any southward travel. They all complained of it being uncomfortably cold inside.

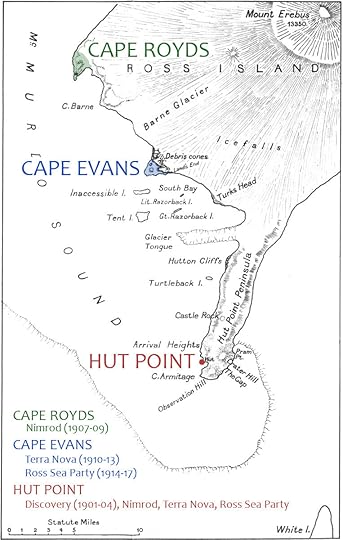

The Hut and RRS Discovery in winter quarters, with the two iron-free auxiliary huts (now gone) for magnetic work. McMurdo Station is now built on the gentle slope you see behind the Discovery’s masts. Photo from the Royal Society collection.

And it was cold. Not that I noticed much, beyond corroborating historical reports that it somehow seemed colder inside the hut than outside. Antarctic cold is a funny thing: You are certainly aware that it is cold, but it is a surface sensation only, and doesn't feel as severe as the thermometer says it is. Skin exposed to the air registers the fact it is cold, but even at -20 it didn't go any deeper than that. Compared to the seeping, insidious cold of a damp British morning or an air-conditioned animation studio cubicle, which disregards layers and seems to chill you from the inside out, -20 in Antarctica is really quite comfortable, if you're dressed properly and sheltered from the wind. I barely noticed how cold it was until the tips of my gloved fingers started tingling, which I observed with some perplexity until I remembered the temperature. At that moment I understood how one could get frostbite without noticing, because one's outermost extremities could suffer while one's internal thermostat was still reading as perfectly warm, if not hot. Hence the practice of deliberate, conscious reminders every few minutes to observe the state of one's feet – they would be all too easy to overlook, otherwise.

Lithium ion batteries don't much like the cold, and unlike human bodies they neither generate their own heat nor have a core heat bank to rely on. I got a few photos that first visit, but my phone died as I was taking a video, so I decided to leave the image harvest to another day. The photos in this post are mostly from later (warmer) visits, when electronics were functioning fully and I'd got over the initial awe of being there.

But before I can give you a photographic tour of the Discovery Hut, I need to fill you in on the history, so that you know what you're looking at when you see it, as I did.

As I said before, the hut was built during the Discovery Expedition but hardly used except for storage and, occasionally, a theatre. The next expedition in town was Shackleton's Nimrod Expedition, which arrived in early 1908. The sea ice that year was much more extensive than it had been in 1902, and the furthest south that the Nimrod could anchor was at Cape Royds, twenty miles north of Hut Point. Shackleton had been on the Discovery, though, and knew there were a lot of good things left in the little square hut across the ice, so he sent a raiding party to scavenge some of them and bring them back to Cape Royds. When they arrived, they couldn't get the door open, so they broke a window to get in, which was never repaired. After it had served its purpose as launching point for southern journeys and the Nimrod left McMurdo Sound, the hut filled up with drifted snow which compacted into ice.

When Scott arrived in the Terra Nova – which was also barred from Hut Point by sea ice and so had settled at Cape Evans, fifteen miles north – he found the broken window and the interior of the hut one solid block of ice. This did not do much to improve his opinion of Shackleton. The depot-laying party pushed on south with their supplies, but Atkinson, who had got an infected blister on his heel and couldn't continue marching, was left at Hut Point with Tom Crean; while the depot party was away, they employed themselves in clearing the ice from the hut. Once that was done, they used biscuit cases and the discarded winter awning from the Discovery to build a smaller chamber within the single room, which would hold the heat better, and improvised a blubber stove from discarded bricks and metal in the Discovery's rubbish heap. There are lots of seals around Hut Point so blubber was a self-supplying fuel, as opposed to the very limited quantity of coal which had been brought down by the ship.

Dmitri Gerof (L) and Cecil Meares (R) at the blubber stove in the Discovery Hut, 1911

The only way to reach Cape Evans from Hut Point is over the sea ice, and by the time the depot party returned, that had all broken up and gone out to sea. (I am glossing over The Sea Ice Incident. Check it out if you want some crazy adventure.) There was nothing for it but to wait at Hut Point for the sea ice to freeze again, which took from the beginning of March to the middle of April. This was, as yet, the longest period of occupation for the hut, and was full of tinkering to make the place more liveable. Everyone devised what they thought was the best model of blubber lamp: whatever the design, it smoked with a thick black soot which added to the smoke from the blubber stove. As a result the hut was often thick with smoke and everyone looked like chimney sweeps before long. Crean and Atkinson had done a massive job clearing out the block of ice in the main room, but there was still ice in the cavity between the ceiling and the roof which they could not access, and this dripped on the assembled crowd every time they got the hut above freezing, turning their reindeer skin sleeping bags into a soggy mess. Despite the soot, the 'snipe marsh,' and a diet limited to recombinations of biscuit, seal meat, and the odds and ends left over from previous expeditions, the men all had a roaring good time. Some of them even claimed, when all was said and done, that this was the best part of the expedition.

Just enough to eat and keep us warm, no more – no frills nor trimmings: there is many a worse and more elaborate life. The necessaries of civilization were luxuries to us: … the luxuries of civilization satisfy only those wants which they themselves create.

— Apsley Cherry-Garrard, The Worst Journey in the World

The hut served its purpose again the following November as the jumping-off place for the great effort to reach the Pole. This is its classic role, and what it is best remembered for, when it is remembered at all, but something which I think gets lost and which adds a great deal to the emotional understanding of the place is that it's also the first taste of home for returning parties, the first solid walls after months of living in a tent. For both the First and Second Returning Parties it was a concrete assurance that they had made it, they were back to safety; it was only the matter of a day's walk to Cape Evans from there, which they did all the time. Like reaching one's own freeway exit after a long road trip, the Discovery Hut would be a welcome return to the familiar. It's the first comfort the Polar Party would have been pulling towards in their struggle to get home before the weather broke up for the winter.

But, as we know, they never got there. The next role of the Discovery Hut, and its most poignant, to me, is as the staging point for another southward journey, the one to meet the Polar Party with the dog teams. Atkinson had taken the dogs there after using them to help unload the ship at Cape Evans, but before he could leave he was co-opted to save the life of Teddy Evans , leader of the Second Returning Party, who was dying of scurvy not far away. Atkinson had to find a substitute, so he sent a message to Cape Evans requesting Wright, and if he was unavailable, Cherry-Garrard. Simpson, who was in charge back at Cape Evans, sent both to Hut Point, with the advice that Wright was needed for his particular scientific expertise and that it would be very inconvenient to lose him. So Wright was sent home, and Cherry was chosen to go south. He failed to meet the Polar Party; he and the dogs turned up back at the Discovery Hut exhausted, frostbitten, and unable to do any more work that season. Cherry spent a miserable purgatory in the hut with a strained heart and broken wrist, delirious on painkillers and tormented by the howling wind and fighting dogs, gradually coming to realise that his friends were never coming home.

When the Terra Nova finally left Antarctica for good, they left a large depot of food at Hut Point for whoever might come after, an act of generosity whose prescience was not long in the proving. Shackleton's Endurance Expedition is famous for the ship getting crushed in the ice and the last-chance boat voyage to South Georgia to find rescue. Fewer people know that that expedition had another half: a smaller contingent of men were sent to the Ross Sea to lay depots for the Endurance party to pick up as they crossed the Antarctic continent, which was the expedition’s original raison d’etre. They had what can only be described as a mindblowingly horrible time. It started with their ship being blown off its anchor at Cape Evans and out to sea before it had been fully unloaded, and got much worse from there. Winter clothing had to be improvised from a heavy canvas tent left by the Terra Nova Expedition, and they depended largely on the food that had been left at Cape Evans and Hut Point two years previously. By supreme effort they succeeded in laying the depots required of them, all the way to the Beardmore Glacier over 400mi/600km to the south, and suffered terribly from scurvy on the way back, one of them dying. The remainder narrowly scraped their way into the safety of the Discovery Hut, to recover their health and wait for the sea ice to freeze, but two decided prematurely that the greater comfort of Cape Evans was worth the risk, and set out over the new ice, never to be seen again. It turned out that their suffering was entirely in vain, as the Endurance party, whose survival they expected to depend on their depots, never so much as set foot on the Antarctic continent.

The view to Cape Evans from the end of Hut Point. Cape Evans is the smudge at horizon level, leftmost of the three long low shapes at upper centre. The sea ice here is walkable, despite the cracks; in May of 1916 it was not.

These are the layers of history with which the Discovery Hut, and all the geography of McMurdo Sound, are imbued. It was one of my great privileges, while a guest of the USAP, to be a portal to the Heroic Age for many people who were mostly unaware of what had passed before the building of the American station. It's harder to transmit the tangible immediacy of the history via the internet, but I hope this and the next post will get you some of the way there.

January 11, 2020

Induction McMurdo

Here's the thing about arriving at McMurdo: It's kind of like diving into your first week at college. You have a series of orientation sessions, a bunch of classes in different buildings with random numbers, and you meet a lot of new people with names and roles that are hard to keep straight, while also being offered a wide range of interesting extracurricular activities and trying to navigate the intranet to find the information you need or missed along the way. On top of this, you have to learn the strict and unusual rules around getting your food and sorting your garbage, and adapt to the unwritten conventions and jargon of the society.

A starter:

155 – The big blue building which contains the Galley as well as a number of useful offices like Lodging, Gear Issue, and Recreation. Noticeboards and the Lost and Found are here too. Essentially the hub of the station.

Galley – the cafeteria. To prevent spreading germs, one must always do time at the handwash station before entering the Galley, even if one has just been to the bathroom and thoroughly washed one's hands there. The handwash station is a regular rendezvous point.

Crary – the building where most of the scientists have labs and/or offices. It has three sections, or 'phases,' connected by a downward sloping 'spine.' Phase 1, at the top of the slope and nearest 155, has an upper floor with a conference room-cum-library. My desk is in a dark little room just off the library, which has been set up with cubicles. The best views in McMurdo are from the library windows.

MacOps – the communications hub, which handles radio traffic amongst other things. When you leave the station you have to check out with MacOps.

The SSC – stands for Science Support Center. Lots of classes in the classroom here. Otherwise it's a staging area for science teams heading out into the field.

The BFC – stands for Berg Field Center. The warehouse of supplies (tents, sledges, stoves, pee bottles, etc) and where things go to get repaired. Denizens of the BFC are a tribe unto themselves and they have a most atmospheric lair on the upper floor.

Helo – pronounced hee-low: a helicopter

Snow machine – a snowmobile

The 203s – three interconnected dormitories, numbered 203a, 203b, and 203c. I am in 203c. They are two storeys; off a long corridor are about twenty double-occupancy rooms, with a bathroom for men and for women on each floor, and a common area on the ground floor. They are being torn down in February and replaced next season, so it is a bit surreal to be living there.

Here is what my first three days looked like:

Wednesday 13 November

16.30 – Arrive. Orientation video. Receive dorm assignment and keys.

17.15 – Get onboarded with IT, set up network login and WiFi access

17.30 – Walk up to the transport building to receive luggage and haul it (with vehicle and coordinator assistance) to dorm. Gratefully change out of bunny boots into regular boots and feel 20lbs lighter, possibly literally.

18.30 – Dinner with coordinator. Introductions to many new and exciting people.

19.30 – Science lecture in Crary; tonight's is about the ongoing study of Weddell seal pups and at which stage in development they acquire the skill of hyperoxygenating their tissues for long deep dives. A bespoke seal-sized metabolic chamber has been built for this purpose. The pups in the study are named after favourite candies.

21.00 – Stagger into bed

Thursday 14 November

06.45 – Meet coordinator for breakfast

07.30 – Inbrief at the Chalet (administrative hub) where department leaders and new arrivals introduce themselves and explain what they do.

09.00 – Harassment Awareness training. We had to do anti-harassment training every year at Disney and this 45-minute class was way better – insightful, pragmatic, realistic – than anything we did there. Well done, USAP.

10.00-12.00 – Me time. I think I tried to write up my journal.

12.00 – lunch with coordinator, meeting more new people

13.00-14.00 – more me time. I think I tried to answer some emails. It can take about five minutes to send and receive an email in HTML Gmail, on daytime McMurdo bandwidth, so it takes a while.

14.00 – picked up my communications radio, got briefed on how to operate it and the communications protocols. The comms team have a stuffed husky mascot named Apsley.

15.00 – Visited the Discovery Hut

16.00 – walked uphill against the wind back from Discovery Hut

17.30 – dinner, meet the other Artists & Writers under my coordinator's wing. They have just come back from the Dry Valleys. Ian Van Coller is a photographer; Todd Anderson is a photographer and printmaker. Together they are documenting the disappearing glaciers of the world. See The Last Glacier.

18.00 – History Club

21.00 – Collapse into bed

Friday 15 November

06.45 – Breakfast

08.00 – I was supposed to take Core Training – the introductory briefing on ways and means of McMurdo (trash sorting, the water system, the taxi/shuttle system, medical centre, etc) but in light of the parlous state of the sea ice this year, my coordinator wanted to get me on a snowmobile ASAP so I was ushered instead into

09.00 – Snowmobile Theory, i.e. how to start it, how to drive it, how not to tip over going around corners. This was entirely indoors with a specimen snowmobile. The Snowmobile Practical would be a few days later but I had to have theory first, and there was an opening here.

12.00 – rendezvous with coordinator at my desk, then lunch

13.00-16.30 – Antarctic Field Training. This consisted of a series of lectures and videos interspersed with practical demonstrations, designed to familiarise oneself with the contents of one's survival bag, which is taken with you every time you leave base, in case you're waylaid by a blizzard. We learned how to set up and run the Whisperlight stove (similar in theory to a Primus but with the burner and fuel tank as separate entities) and set up the standard issue tent. I learned the extremely clever Trucker's Hitch knot and forgot it about half an hour after class ended. In fact it went much longer than the allotted time because the power kept going out whenever we tried to watch one of the several requisite videos, so eventually Helicopter Training was postponed to 7.30 the following morning.

18.00 – Dinner. Met the new arrivals from today's C-17, a film crew making an episode of the NatGeo-Netflix-Disney series One Strange Rock.* Despite the American commission, they are in fact British, and one of them was cameraman on the show about the restoration of the Cape Evans hut, which has hitherto been my best point of reference for that interior space. Instant friends. Power outages continued. Went to bed during one particularly long one.

Saturdays are work days here, so the schedule didn't let up then. The standard work day is 7.30 - 17.30, a ten-hour day which significantly favours morning people, of whose tribe I am not. One would think that, in 24-hour daylight, circadian rhythms would be more or less malleable, but I never succeeded in going to sleep before 10 or finding it easy to wake up before 7. People complain of a certain befuddlement in Antarctica – constantly losing things, inability to concentrate, loss of vocabulary – and they call it McMurdo Brain, but my experience of working 60-hour weeks at Disney makes me think it’s probably chronic low-grade exhaustion. When I stole time for a nap or was allowed to sleep in, I felt noticeably sharper.

This particular Saturday, after the makeup Helicopter class, was entirely given over to Sea Ice Training. That was such a full and interesting day that I will give it a post all of its own in the future.

*One Strange Rock is still on Netflix until January 15th, at which point (I assume) it moves to Disney+. This team worked on ep.10, ‘Home’ – if you only have time to watch one episode, watch that one!

Sarah Airriess's Blog

- Sarah Airriess's profile

- 20 followers