Sarah Airriess's Blog, page 4

June 20, 2020

Scene 5: Int. Cape Evans, the Opium Den

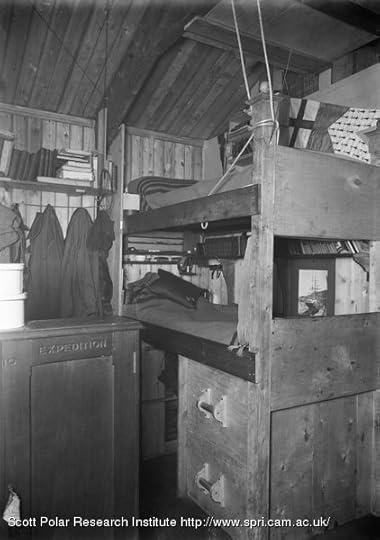

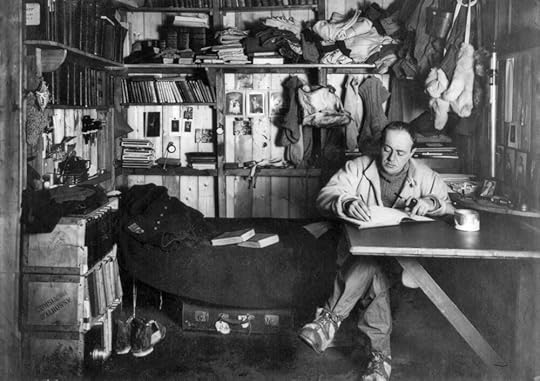

As we work our way around the perimeter of the Cape Evans hut, we have ended up at the section directly opposite the Tenements, or in nautical terms, port amidships. This is mostly taken up with an enclosed space where the geologists lived, but the first thing we see is the pair of bunks known as 'The Palace.' In 1911 it looked like this:

Edward 'Marie' Nelson, marine biologist, was in the top bunk, with Bernard Day, mechanic, in the bottom one. Day was the one who installed the acetylene gas lighting system in the hut, and helped build the bunks. The hut at Cape Evans was being constructed while most of the party was out laying depots for the following season; as Day and Nelson happened still to be around, they were able to put a lot of care into their bunks, and the relative finery won it the name of 'Palace'. I started with the historical photos this time because, while The Palace is still palatial, its relative refinement really shows how much it has aged:

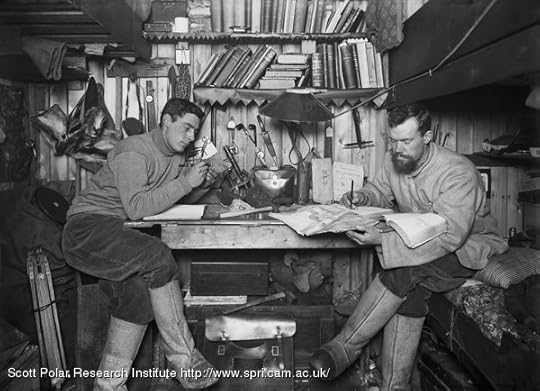

The wall which forms the back of The Palace is one side of the cubicle which housed geologists Frank Debenham and T. Griffith Taylor, as well as Norwegian professional skier Tryggve Gran. There are, as far as I know, three contemporary photos of this cubicle, all shot from the same angle and ostensibly at the same time. Here is one with Debenham (L) and Taylor (R) – it is a slightly wider angle than the one which includes Gran so I hope he can forgive me for leaving him out:

This hut-within-a-hut got nicknamed 'The Opium Den,' on account of the red paper lining the shelves (the zigzag-cut stuff in the photo) and the plush curtain hung across the entrance. To get the shot above, Ponting must have stuck the camera lens in the door, because from the outside – which I hadn't seen before – one realises that the modern translation of 'opium den' is 'crack house.’

With the exception of Ponting's darkroom, it is the darkest part of the hut, and even the surprisingly sensitive night setting on my phone struggled with it. I have applied my limited Photoshop skills to the photos so you can make any sense of them at all, but they are not works of art. However, they tell me enough to draw the place, which is what they're really for after all.

First, Debenham's bunk:

For some reason I'd got the impression he was bunked under Gran, but no, he was in an upper bunk across from Gran. Below Deb's bunk is a sort of storage area, occupied by – surprise! – rocks, and a case for rocks. Geologists, I tell you.

On the opposite side of the den, Gran's bunk is on top. With the awning up it actually looks rather cosy, and it would have been best situated to get the warmth and smells from the kitchen, so probably was. But ... he seems to have written on it ... in blood? Way to be metal, Gran!

I was unable to make head or tail of the blobs until I asked one of the Antarctic Heritage Trust people what it said; it is no eldritch inscription after all, but simply 'TWO YEARS GOOD FRIEND' with the date and Gran's initials. You can see this if you look not at the pigment but at the shiny spots where the paint had originally been placed – it seems to have slid down the wood in the intervening years, to creepy effect.

Griff's bunk is below, with a few items collected on it, including one of the few pillows remaining in the hut, a knife sheath, and that funny half-ski-stick bamboo which also turns up at Cherry's bunk. Could you hazard a guess as to what that is? Here's a closer look:

Also, let's admire Griff's dedication to dental hygiene, with two toothbrushes. Well done, Griff.

That's pretty much the end of the tour. I hope you have enjoyed the walk round, and that it gives some perspective in these times of sequestration – these men were more cut off than any of us, with less personal space, for two whole years, some of them. And no internet!

June 6, 2020

Happy Birthday, Captain Scott!

On June 6th, 1868, Robert Falcon Scott was born near Plymouth, in southwestern England. June 6th, 1911, he celebrated his forty-third (and last) birthday with his expedition members in their hut at Cape Evans:

It is my birthday, a fact I might easily have forgotten, but my kind people did not. At lunch an immense birthday cake made its appearance and we were photographed assembled about it. Clissold had decorated its sugared top with various devices in chocolate and crystallised fruit, flags and photographs of myself.

After my walk I discovered that great preparations were in progress for a special dinner, and when the hour for that meal arrived we sat down to a sumptuous spread with our sledge banners hung about us. Clissold’s especially excellent seal soup, roast mutton and red currant jelly, fruit salad, asparagus and chocolate – such was our menu. For drink we had cider cup, a mystery not yet fathomed, some sherry and a liqueur.

After this luxurious meal everyone was very festive and amiably argumentative. As I write there is a group in the dark room discussing political progress with discussions – another at one corner of the dinner table airing its views on the origin of matter and the probability of its ultimate discovery, and yet another debating military problems. The scraps that reach me from the various groups sometimes piece together in ludicrous fashion. Perhaps these arguments are practically unprofitable, but they give a great deal of pleasure to the participants. It’s delightful to hear the ring of triumph in some voice when the owner imagines he has delivered himself of a well-rounded period or a clinching statement concerning the point under discussion. They are boys, all of them, but such excellent good-natured ones; there has been no sign of sharpness or anger, no jarring note, in all these wordy contests! All end with a laugh.

– R.F. Scott, 6 June 1911

May 23, 2020

Scene 4: Int. Cape Evans, Science Corner

Having exited the cosy nook of the executive cabins (which you can just see in the image below, to the left), we are now standing with our back to the rest of the hut, looking at one of the prominent structures built into the interior space: the Darkroom.

Herbert Ponting was a very serious photographer, and was brought along on the Terra Nova Expedition not just to document the science and geography, but to communicate the endeavour in the press back home. He took hundreds of photos and even shot some film – a most precious reference for someone trying to bring the dead back to life. This darkroom was not only his workspace but also his cabin, with a bed that folded up against the wall when not in use, and also served as a classroom where he taught his art to some promising newbies on the crew.

Ponting was only here for one winter. The second winter, Debenham – formerly his student – had taken over as official photographer, but the space was also used for some physics experiments that had been moved in from the outbuilding which had formerly housed them. The weather was so bad that second winter, and the other location so hard to keep a constant temperature, that in order for them to be tended consistently they needed to be in the main hut.

Because heat rises, the roof of the darkroom was not only used for storage, but by the biologists for incubating bacterial cultures. The biologists’ bench is to the right of the image above, so you can see it was a very convenient location.

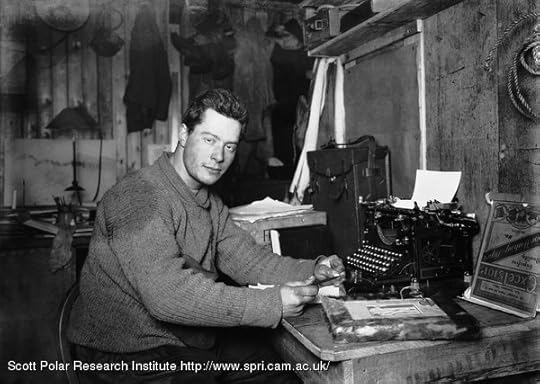

On the front of the darkroom is a small table which seems to have been used as auxiliary space to the main central table, where most people did their work. It’s covered with mechanical and electric bits now, but from the photographic record I know it was also used as a writing desk and taxidermy bench.

Cherry working on the South Polar Times. The window is here covered with a piece of felt or tarpaper.

The interior of the darkroom is, well, dark. Very dark. This was the best I could manage with the nighttime setting on my phone – it actually shows up a lot more than I could make out with my naked eye, even with very good night vision.

The folding bed was on the right, where the low workbench is now.

The darkroom as it appeared just before a winter of continuous use.

Moving to the port side of the hut, now, we get to the laboratory space. This is another of the secret corners which I most wanted to get a sense of. There are more historical photos of this than Wilson and Evans’ bunks, but I didn’t have a proper sense of how it related to the rest of the hut, and especially to Wright and Simpson’s bunks. Well, stand in front of the door of the darkroom, look to your left, and here it is:

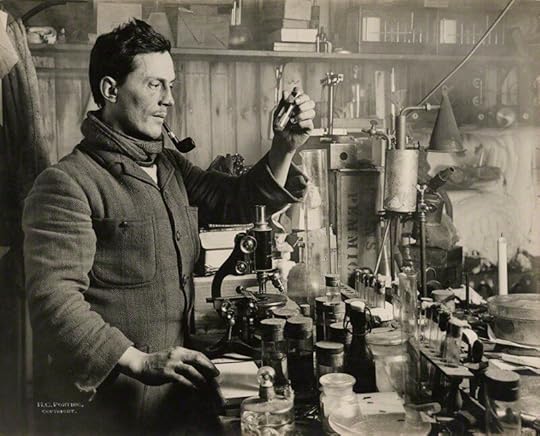

To the right are the bunks in question, which I will get to in short order. Against the far wall is the meteorology lab, dominated by the zinc cylinder of the Dines anemometer, which measured wind gusts and was known in the hut as the Blizzometer. Nearest us is the biology and/or medical bench – it was Atkinson’s domain, anyway, and as such is familiar to me on its own, as this photo has hung above my desk for some time now:

If anyone knows what that contraption is with the conical hood, bent pipes, and brass cylinder, I (and the Antarctic Heritage Trust) would really like to know! It’s on the right side of the historical photo and is lying down on the bench in my modern one. (Atch’s microscope, by the way, is now in Dundee at Discovery Point.)

Now, the bunks! As you can see, unlike the other bunks they run parallel to the wardroom, rather than end-on. While Scott’s men were here they would have been hidden behind the pianola and whatever was stacked on top of it, an arrangement which would have given Wright and Simpson an almost private cubicle to live in, with a window to boot. The pianola was given to Rennick as a wedding present in 1914, and the compact library cabinet which was next to it is now at SPRI, so this corner is much more airy than it would have been when the bunks were occupied.

The window was one of my favourite discoveries. I knew there was a window there, because Nelson’s bench covered in well-lit glassware is possibly the most-photographed location in the hut. What I didn’t know, and wasn’t hinted in anything I’d read or seen, was that you could see the meteorological station on top of Wind Vane Hill from the meteorologist’s bunk.

The official guide says that it’s meteorologist Simpson’s bunk on the bottom, and physicist Wright’s on top. During the second winter Wright discovered that his groggy morning headaches were caused by carbon monoxide from the generator in the lab, whose exhaust vent had got snowed up. I couldn’t see well into the top bunk, but the bottom one has a lovely tableau of personal and meteorological items – those blue arcs are, I think, sunshine recorders.

To get a broader view of the space in this corner and the situation of the bunks within it, here is the view from right next to the window, looking down the length of the hut from the other side of the bunks.

Where we are standing now is at Nelson’s biology bench, the aforementioned most photographed. Because of that, I didn’t take any photos of it myself, but we will see the rest of that side of the hut next time, when we wrap up our tour.

May 9, 2020

Scene 3: Int. Cape Evans, Aft Cabins

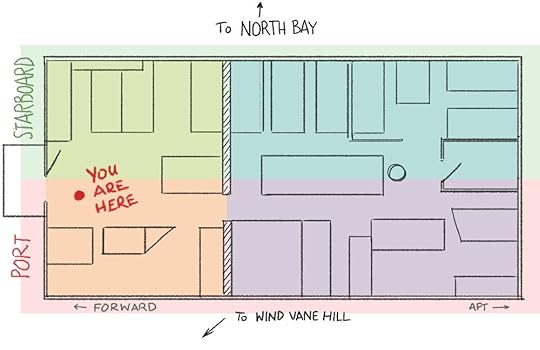

We continue our tour of the Cape Evans hut in the aft starboard corner. For the map of the hut and previous stops, please start with the Men’s Quarters and progress to the Tenements.

Coming out of the Tenements, we proceed down towards the end of the wardroom and find ourselves looking into a corner that is almost, but not quite, its own little room. This is where Captain Scott’s bunk was, as well as that of Teddy Evans, technically his second-in-command, and Dr Wilson, who everyone else considered to be his second-in-command. We will look at Scott’s cubicle first.

There is another historic photo here, of the man himself in his domain.

I have a high-res version of this and it shows the place as I need to draw it, so I deliberately didn’t take any similar shots when I was there, as its modern state is rather denuded. It has also been photographed extensively by every visiting photographer for the last twenty years, so if I really need to find reference for the modern space I can easily find it on Google, as can you. However, there were some small details that I hadn’t seen before and which gave a tangible connection to overlooked everyday life in the past.

A rather worn balaclava at the foot end of the bunk

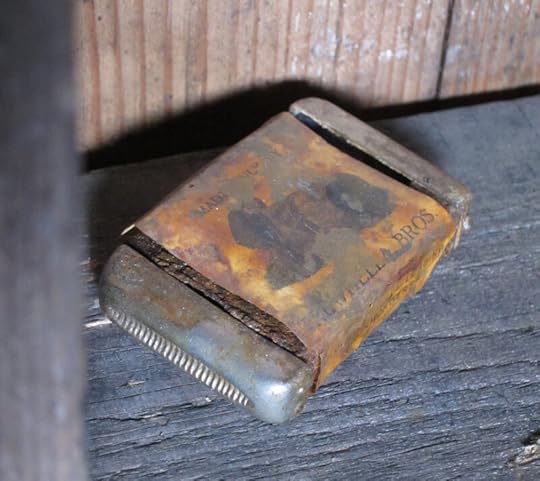

Is this a matchbox? Scott was a heavy smoker … his pipes are gone but perhaps the matchbox was a less attractive souvenir for sticky-fingered visitors of the past.

Some lanterns, which may have been used in the search for Dr Atkinson when he was lost in a blizzard in July 1911.

A stack of socks, viewed close up for texture. The Expedition took several types of sock, including a Norwegian goat hair variety which were notorious for wearing out quickly. These socks have rather a hairy texture so I wonder if they are those.

The thing that really surprised me about Scott’s cubicle was how far the desk was from the bed, as the famous photo makes it look like a compressed space. Looking back at my photos against that one, I see now that he is not writing at the central desk that is there now, but instead at a smaller one that collapsed against the wall, and he’s sitting on his bed, not a chair. If you look closely at the first of my photos above, you can still see the triangular wooden support bracket still against the wall, though the table top is gone. So the large desk that is still there must be what was known as the chart table, and Scott’s collapsible desk was his writing desk. Learning new things all the time!

From Scott’s cubicle, you get a good view into one of the much less well=photographed parts of the hut, the nook that was shared by Lt. Evans and Dr. Wilson.

Evans on the left, Wilson on the right

Having only ever seen one photo of this space, I guessed it was overlooked by photographers because it really wasn’t much to look at, but trying to photograph it myself I think it’s also because the light conditions are extremely awkward. The light from the window shines bright on the wall to the right and on the table in the foreground, but Teddy’s corner is in deep darkness. The human eye can compensate for this somewhat, but cameras want to use one exposure setting for the whole image, and it just doesn’t work! This was the best I got, with the nighttime setting on my phone and some help from Photoshop. It seems like a lot of work for a middling photo of an unimpressive space, but the whole reason I was there was to get into the corners that are mostly left out of the photographic record, and this was one of the most important ones.

The shelves around Wilson’s bunk are full of medicines and medical supplies – you can see piles of rolled-up gauze bandages in the upper right. Wilson wasn’t the chief medical officer on the expedition (that was Atkinson, whose bunk we saw in the Tenements) but he had qualified as a medical doctor and had been Junior Surgeon on the Discovery, so they are not misplaced.

On his bed is a rather comfy-looking sweater:

Oh all right, here’s a shot of Scott’s cubicle. See? Empty. But I hadn’t seen it from Wilson’s bunk before, and this gives you more of a sense of space.

If you’re very observant, you may spot my minder trying not to be seen.

To the right is Ponting’s darkroom, where the picture at the top of this post was developed, and beyond that another of the largely unphotographed corners of the hut. But that is an adventure for next time!

April 25, 2020

Scene 2: Int. Cape Evans, The Tenements

As we walk deeper into the hut from the mens’ quarters, coming through the gap in the bulkhead, the view looks like this:

Today we’re going to look at the section to our left, or mapping the hut in nautical terms, starboard amidships. This is the area of the hut that was known as ‘The Tenements’ for how crowded and relatively sloppily built the bunks were. One very famous photo of The Tenements has all its residents in their places and shows this area at its most lived-in – it was October 1911, everyone had spent a winter in their little domains, and were about to set off on the journey for the Pole.

Clockwise from lower left: Apsley Cherry-Garrard, ‘Birdie’ Bowers, ‘Titus’ Oates, Cecil Meares, and ‘Atch’ Atkinson. Birdie and Titus would not see their bunks again after they left; Meares returned briefly but left with the ship in March 1912, which left only Cherry and Atch for the second winter.

This is The Tenements as they appeared in November 2019:

The first thing that struck me about seeing the Tenements in person was how small they were. Scale in Ponting’s photograph is thrown off partly by the framing, but mostly by everyone lying down aside from the shortest of the Tenements’ tenants, Birdie Bowers. To my surprise, I could easily see over the top bunks, and I am only 5’6”.

We’re going to start at the forward end, with Cherry and Birdie’s bunks. Cherry is the main character in my graphic adaptation of his book, and I’ll be drawing a lot from his point of view, so getting a really solid idea of his bunk area was a must.

Although the Tenements photo has everyone with their heads at the public end of their bunks, they probably slept the other way around, for such privacy and quiet as one could find with 25 men in a 50’x25’ room. While the Cape Evans hut feels like it’s full of stuff now, comparing the modern hut with the Tenements photo above, you’ll see just how much more stuff there was back in 1911!

Cherry was a great fan of Kipling, and brought his whole collection with him – these likely lived on the small shelf you can see against the hut wall. The bed is now covered with stray bits of clothing, and one of the socks has Cherry’s name sewn into it, so I assume the others have been identified as his too.

The ladder leads up to Bowers’ bunk, so let’s take a look at that …

This is the foot end, which he also used as a desk, as you can see in the Ponting photo. The boards blocking it off from the main hut weren’t there in October 1911, so they may have been added the second winter, but Scott’s men weren’t the only ones to have used this hut – a couple of years after they left, Shackleton’s Ross Sea Party moved in, and one of them may have moved into Bowers’ bunk and sought some extra privacy.

But the real treasure of Bowers’ bunk is at the other end …

It’s his hat! The actual Green Hat of legend – less green than I was expecting, but definitely the same one as in all his photos. I was so pleased that, of all things, it should still be here – that he didn’t take it on the Southern Journey, that the Ross Sea Party had let it be, and that it hadn’t been pilfered in the years of uncontrolled hut visits before the AHT took charge.

The photo below the hat, I suspect, originally belonged to Cherry. He had found a photo of the actress Marie Lohr in a magazine and wanted it for a pinup, but one of Ponting’s photographs was on the other side of the page. and Ponting thought that was the object of his affection. He offered to mount it nicely for Cherry, which would have meant gluing the lovely Miss Lohr to the mounting board, and with some flustered embarrassment Cherry’s intentions came out. I had some photos of Marie Lohr; none of them are the photo in the hut, but she looks to me like the same person. How it got from Cherry’s bunk to Birdie’s I don’t know – the AHT have been very careful about giving items to the correct people, so it must have been found there. Perhaps the member of the Ross Sea Party who took Birdie’s bunk liked the photo and moved it up there.

My trip here was, in large part, to get photos that were necessary to my storytelling but unlikely to be found anywhere else. The Cape Evans hut is extremely well documented, but there are angles which are important to the reality of living there which do not necessarily make glamourous shots for publication. One of these was the view from the Tenements to the rest of the hut, rather than into the Tenements. It happens also to give you a good sense of how crammed they were.

The structure on the other side is the geologists’ cubicle, which we will get to a couple of posts from now.

Immediately to our left here is Titus Oates’ bunk. He was in charge of the horses, so it’s piled high with horse stuff.

The fringe in the middle is, in effect, pony sunglasses – it was originally dyed brown and would have hung down over their eyes like hair, blocking out a large portion of the harsh sunlight and snow glare. Ponies can get snowblindness too!

Behind us, from where we are standing looking at Titus’ bunk here, is Meares’ bunk, and below that, Atkinson’s. Atkinson, who alone shared the Tenements with Cherry through the miserable second winter, was in command of the expedition at that point; as doctor as well, he had a very heavy job in keeping the bereaved and stir-crazy men on the right side of health, both physical and mental. As leader, he could have moved into Scott’s much more comfortable and private space – that he didn’t, and that the thought of such a thing didn’t even turn up in anyone’s journals, says a lot about him and all of them. He stuck it out in his Spartan cubbyhole, within view of his best friend’s now deserted place, and was there for everyone.

It was here that I spotted the thing that, of all the amazing things in the hut, nearly brought a tear to my eye.

If you look at the Ponting photo at the start of this post, you will see that the string once held a spoon! I don’t know if it belonged to Meares or Atch – in the photo the string doesn’t look long enough to reach either of them. I think of it as ‘Atch’s spoon’ but that may be just because it’s hanging by his face; Meares seemed more the type to be possessive about silverware. Wilson’s cartoon in the South Polar Times suggests there was once an entire cutlery set hanging here, but that may have been a comedic exaggeration.

People visiting the hut often say it feels like the people are still there, or that they could walk in the door at any moment. I wanted to feel that, but I have to confess my experience was quite the opposite: they were gone, very gone, and had been for a very long time. Finding the string there without the spoon summed that up that better than anything.

Our next stop is the stern of the hut – Scott’s cubicle, Ponting’s darkroom, and the lab. Before we go, let’s take one look back at the Tenements.

April 11, 2020

Scene 1: Int. Cape Evans, Men's Quarters

It’s time to step into the Terra Nova hut. Look, the door is already open.

It’s open because the Antarctic Heritage Trust is here doing their annual check-up. Just because they’re here, though, doesn’t mean you don’t have to do the same boot-brush-and-sign-in routine that you do at Hut Point, so you do that. Here’s the guestbook. Have a go.

Since we’ve got a moment here, allow me to draw your attention to the cloth hanging above the wood plaque. It’s a plankton net, probably one of the ones Nelson used as he studied the biology of the sea over which we’ve parked our snowmobiles. At our feet is an enormous bright red fire extinguisher, which is very important – ironically, on this continent of ice, the greatest threat to the historic sites is fire. We do not want this hut to burn down. No, no.

Between the sign-in table and the fire extinguisher is a stack of skis, and I’d like to draw your attention to one in particular.

This ski (and its partner, not pictured) belonged to Edward Leicester Atkinson, expedition surgeon and commander during the second winter, after Scott had died. They were returned to the Antarctic Heritage Trust 100 years after Atkinson left Cape Evans and are now back home. It’s good to see them here.

Now we can step inside, through the small vestibule which had been the original entrance to the hut, before the porch was built. The cylindrical device for generating acetylene gas from calcium carbide should be here, but the AHT is conserving or photographing it or something, so it’s in pieces somewhere else. That’s fine, because what we really want to see is this:

We are standing in the mens’ quarters – the hut is arranged like a Naval ship, with the officers at one end and the ‘men’ – the ordinary sailors – at the other. As the men’s quarters on a ship tend to be at the front end, we can call this area ‘forward’ and the officers’ area (which you can see down the passageway) ‘aft’, and therefore the sides of the hut are ‘port’ and ‘starboard.’ I will use these terms to describe where we are because they don’t change relative to which direction you’re facing, as left and right do. In this picture, port is to the right and starboard to the left. To orient yourself with the outdoor photos, the sea, from this viewpoint, is to starboard (left), where the sun is coming in, and Wind Vane Hill is a little forward (behind us) to port (right).

Everything is easier with some visuals!

This post, I’m just going to be showing you around the forward part. Future ones will cover the officers’ quarters, in sections, because there’s a lot to see and I have so many stories to tell you.

Right, clear as mud? Let’s continue!

I have walked around this hut many, many times in my mind, aided by historical photos and some modern ones, so actually stepping through that door and seeing it for myself was a very emotional experience. The wash of feelings was cut short, though, by noticing this object on the mens’ table:

It was so exciting I put aside my feelings entirely, because I didn’t know this thing still existed! It doesn’t look like much, but it was a tabletop game that might possibly have saved the mental health of the expedition, their second winter. Silas Wright can explain:

I do not think any chess games or indeed card games were at all common, but someone in the party had received a toy which proved to be most popular with all. I think it may have been called bagatelle; at any rate there was a wooden board about 4 feet by 5 feet, with a number of wooden balls, approximately spherical, a miniature billiard cue and a bridge across one end of the board with a number of arches which were wide enough to permit the passage of the balls. Of course all the balls did not long retain their original spherical shape and there was one which had early lost an appreciable amount of wood to which Demetri (I think it was) gave the name "British Pluck." Its movements when struck by the cue were extremely erratic.

I mention this childish game we all played. It may surprise my readers (if any), but it does give me a chance to say that the reversion to childish games was of real value in holding the party together. So firmly do I believe this that I would suggest that no small party such as ours should be without the wherewithal to play "darts" and "shove ha’penny" which do not really demand the surroundings of a bar as in the old English village "pub.” (Silas, pp.281-2)

They set up weekly bagatelle tournaments, where the winner would get a ‘medal’ and the lowest scorer would be ‘the Jonah’ for a week. That this vital piece of equipment should have survived to the modern day, and be displayed so prominently, was a tremendous joy. It may have lost its broad base board, but it’s far better than not existing at all.

Anyway. The wall behind the table, continuing the nautical tradition, was known as the ‘bulkhead’, and was made of packing crates full of food, stacked on their sides so they could be opened and their contents removed as necessary, then the empty crates used as shelving. In the most recent photograph I had seen of the restored hut, the bulkhead was largely missing, so I was glad to see it back. It looked like it had been largely reconstructed out of crates from outside, as the paint had prevented some weathering before finally weathering away itself.

Here is a historical photo of Tom Crean and Taff Evans mending sleeping bags against the bulkhead. You can see the shelving unit behind them, though back then it stood in front of the bulkhead rather than forming a part of it.

This bulkhead is the source of much criticism of Scott’s leadership style in modern times, dividing the officers and men into two units. I am not here to pass judgement, but I do invite you to consider the following question for yourself: If you were at a work retreat that was going to last for two years, would you want to sleep in the same room as your boss? Call me ‘not a team player’ but that wall would have been my favourite thing in the hut.

OK, to get your bearings, turn around, and here is the door we came in:

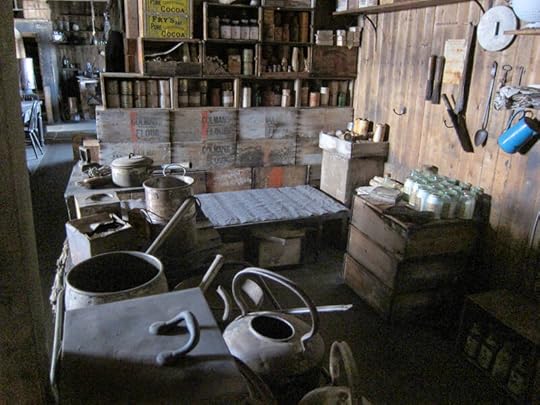

If you keep turning, you will be facing the galley, which is to port of the door. Nearest the door is the cook’s table, strewn with things useful to the preparation of food.

Turn slightly further, and you can see the cook’s bunk. For the first winter, Thomas Clissold (pictured above) slept here. He was first and foremost an artificer – like a machinist – and found novel ways to advance his culinary arts through metalwork, including, quite possibly, that tray on the table, which might have been used to make sausage rolls. His most cunning invention was a rising bread alarm: he would wake up early, get the dough going for the morning bread, then put it under his device. Once the dough rose to the desired height, it would trigger a bell and a flashing red light, which would wake him from the couple hours’ extra sleep which his ingenuity had earned.

Our tour will continue next week with the starboard side of the officers’ quarters, the section historically known as ‘The Tenements.’

March 28, 2020

Nova Goes Antarctic

We interrupt our regular Cape Evans programming to bring you videos! Actual professional videos of Antarctica! One of my favourite TV shows growing up was PBS’ NOVA series, so it was a real joy to find that they’ve done a YouTube series based at McMurdo, talking about the science there, but also giving you a pretty good sense of what it’s like to live there, which is what Episode 1 is all about:

I am immensely pleased that Elaine Hood gets such a starring role in this, as she was my coordinator and pretty much makes everything happen for the Artists & Writers, and media people like PBS.

Episode 2 is about the Weddell seals, and you will recognise the setting from two posts ago!

The seals are often the only animals you see, unless you get in the way of some skuas (also pictured in the above episode). They lounge around on the ice, basking in the sun like cats, and more often than not snoring peacefully. I never got up close and personal with them like these people did, so it’s great to get that insight into seal life (and seal scientist life).

You can also have your own Antarctic Adventure on a website they’ve built for the series: Nova Polar Lab. I haven’t yet played with it myself, but it looks like it has a lot of great stuff.

It seems the series updates on Wednesdays, so subscribe if you’re interested, and please leave a comment to help the algorithm! Here are the rest of the videos they’ve uploaded so far:

Probably my favourite episode, not just because it starts in the Cape Evans hut but because it is full of wonderful wonderful people like Anne Todgham and Britney Schmidt:

In this video you find out just how super awesome Britney Schmidt is:

Some necessary facts of life!

March 14, 2020

Cape Evans, Exterior

I have enough photos of the interior of the Cape Evans hut to fill twenty posts – there will probably be four – but to get a good idea of the context for the hut, let’s do a little exploring outside, first.

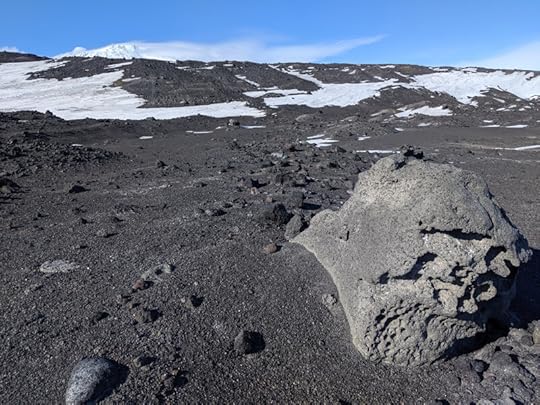

If you are standing facing the hut as in the photo above, the outward tip of Cape Evans is off to your right, and it attaches to the rest of Ross Island and the slopes of Mt Erebus to your left. That is the direction we’re going to go, because we want to climb the Ramp, that steep slope of volcanic scree which makes the border between the ice cap of the island and the exposed rock of Cape Evans.

Once you get away from the human area, Cape Evans looks more like the moon than anywhere you’ve been. There are odd-shaped porous igneous rocks strewn everywhere, and everything is filled in with volcanic grit, loose like sand. Every so often there’s a big rock that has been sculpted by the wind, volcanic forces, or both. These are often studded with rhomboid crystals of feldspar, making these rocks kenyte, so named because it was first identified on Mt Kenya, formerly a volcano like Erebus. It is a very rare form of rock, globally, but Cape Evans is full of it, and when the Terra Nova emptied her belly of Expedition wares, they took many tons of kenyte back to New Zealand as ballast.

Spot the skua. It’s watching. Always watching.

When Cape Evans was first explored on the Discovery Expedition, it was called the Skuary for all the nesting skuas. Like the pair at Hut Point, the skuas at Cape Evans did not yet have any eggs, but they had picked their spots and were hanging around in pairs watching me suspiciously. A few times, one flew low overhead, just to remind me who was in charge. I tried to spot their sites before I stumbled across them, which wasn’t easy to do as the birds are about the size and colour of the rocks, but the blast pattern of white droppings was usually a good sign. I made it all the way through the danger zone unscathed.

What had looked like a clear shot up a moderate but climbable slope turned out to be rather a tough climb, at least as much for the loose grit as the incline. I only got halfway up before getting much too hot to continue, but that was high enough to get a panorama which puts the hut, the cape, and the islands in context from the landward side.

A larger version of this image can be found here. The hut is that teeny tiny triangular thing at the far right end of the photo. I told you Inaccessible Island was big.

From up here I could see that a far more sensible way to climb the Ramp was to follow the ridgeline from Wind Vane Hill, and made a mental note to try it that way in future. (Spoiler: too many skuas.) I could also see some of the famous debris cones. These very regular conical hillocks mystified the explorers, who thought they must be some sort of volcanic feature, but on excavating one they found it was just a uniform pile of gravel. Eventually it was hypothesised that they had been great boulders that had weathered in place and simply fallen into the cone shape as they broke apart. I don’t know if this theory has been updated. I was surprised – I really shouldn’t have been – that they looked exactly like Wilson’s drawings of them.

Two debris cones can be seen near the top of the ridge. See also the skua nest sites in the foreground.

I hastened back to the hut, and on approaching it got to appreciate some of Cherry’s handiwork.

The House that Cherry Built, v.2

In preparation for the Winter Journey to Cape Crozier, Apsley Cherry-Garrard set about constructing a stone igloo, seeing as building materials at Cape Crozier were likely to involve stone and ice and not so much of the lovely sticky snow that is good for making the traditional sort of igloo. The structure you see here is, in fact, Igloo No. 2 – it was originally constructed near the Magnetic Hut, but when he tried to install a blubber stove, Simpson banished him from the environs as the soot was bound to mess up their atmospheric radiation readings. So he carried each of the stones resentfully down the beach to reconstruct it here. That was quite a long way:

The Magnetic Hut is where that blue square is, on the snowy slope. What you see there is a white casing (the blue is the shadow side) as the magnetic hut was (and is) insulated with asbestos.

Up Wind Vane Hill is another important view of Cape Evans. Of course, you get the view down to the hut and North Bay, which still looks pretty much exactly like the historical photos except, bizarrely, in colour:

What I really came up here to see, though, was the view in the other direction. Many years ago I wanted to do an illustration of someone watching from the top of Wind Vane Hill for anyone approaching from the south, but could find no photographs of that view. It’s a very important view as it’s a direct visual link with Hut Point, and once the telephone line had been severed, the only way to communicate. Well, now I was in a position to get that view for myself:

There’s that million-dollar view. Use it responsibly.

I’ve done my best to correct it in Photoshop, so perhaps you haven’t noticed that there’s a peculiar quality to the light in these last few photos. That’s because, the day I took these pictures, the sun was doing this:

Though it wasn’t planned as such, it would turn out to be my last visit to Cape Evans. I had a small inkling at the time that it might be, so tried my best to tie up all my loose ends while I had the chance. These effects were caused by the high-level moisture of an approaching storm, and that was the only time in my month on the ice that I saw such a display. It was bittersweet but much appreciated that it happened to be here, of all places.

February 29, 2020

The Road to Cape Evans

Having done Sea Ice training at last, I was clear to head out on snowmobile. My coordinator’s intent had been to do a ‘shakedown’ one day – a practice run, to get used to the vehicles, how to load and tie down the sledge, a chance to get things wrong when it doesn’t really matter – and go to Cape Evans the next, but the morning of the shakedown she said ‘It’s a beautiful day, let’s combine the two.' Thus was initiated a de facto rule of my month in Antarctica: One Must Only Ever Go To Cape Evans By Surprise. I ended up going three times, all by surprise, while every excursion that had been planned, even the night before, fell through.

Having been the headquarters of the Terra Nova Expedition, Cape Evans was obviously central to my research and the most important location for me to visit: I’m going to be drawing people doing stuff there for the next decade, probably, and I need to be able to place myself in that space to depict it truthfully. The hut itself is copiously documented, and while dropping in there was obviously valuable to me, the urgent holes in my knowledge were the less photogenic but no less important surroundings of the hut. How far was it to walk up Wind Vane Hill? How far to the Ramp? What was the Ramp? What did the named landmarks between Cape Evans and Hut Point look like, and how did they relate to one another? There was a lot of travelling done over that route – perhaps not quite as frequently as you’d visit the grocery store, but it needs to have that degree of familiarity.

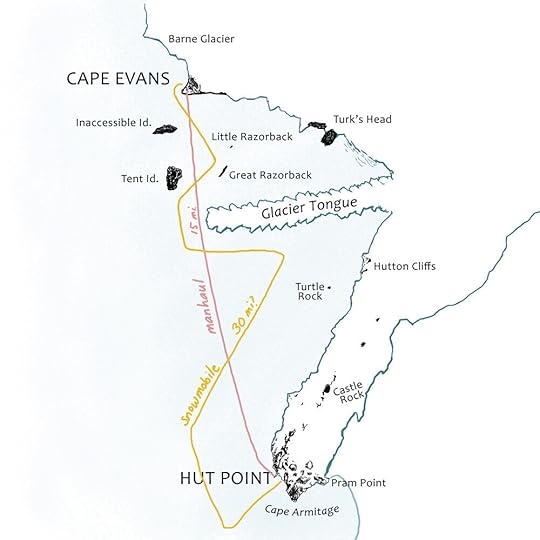

So when we set off on a bright and amazingly balmy November morning, aside from learning the basic practicalities of snowmobile driving, I was keen to document as much of that route as possible.

These are the Heroic Age placenames, but our route wasn’t quite the historical one. Given the iffy sea ice, the 2019 road accommodated modern vehicles with significant detours around jumbled ice and unsafe cracks. The route is drawn from recollection and may only vaguely resemble the actual road.

You can’t see Mt Erebus from McMurdo, but I knew from Sea Ice training that only a little way out on McMurdo Sound, the Ross Island panorama comes into view. Once we’d made our turnoff onto the main road and had a clear shot of our objective, I captured it.

L-R: Snowmobile, Elaine, Dellbridge Islands (Tent and Inaccessible superimposed), Mt Erebus, Arrival Heights

A little further on, I got one facing the other direction. This is what you would have seen any time you were setting off for a grand adventure to the south.

L-R: Arrival Heights, Hut Point, from behind which can be seen the tail of White Island, then Minna Bluff, Black Island, and the foot of Mt Discovery

Once clear of Arrival Heights, I got a panorama of the whole of Erebus Bay, with several features I was finally seeing for the first time. Probably the biggest surprise of this trip was finding out just how low Glacier Tongue was. When you see it on a top-down map, or a satellite photo, it’s a hugely prominent feature, but unless you’re very near to it, it is perfectly possible to look right over it to what’s beyond.

L-R: Tent Island, Inaccessible Island, Great Razorback, route marker flag, Turk’s Head, Mt Erebus, Turtle Rock, Hutton Cliffs

Here we were further into the bay than the usual route would have been, but it means we got a better view of the Hutton Cliffs than we would have done otherwise. They are not so much cliffs as hills which, between them, create a cliff of ice and snow. In the frustration of waiting for the sea ice to freeze and allow them back to Cape Evans, the Terra Nova men frequently discussed alternate overland routes back, often starting up the Hut Point Peninsula and going down the slope north of the Hutton Cliffs, so it’s nice to see what they meant.

The Hutton Cliffs

As we approached Glacier Tongue, the ice effects on Erebus really started to shine. The Sea Ice Master had previously been a mountaineer, and the other person training with me was a skier; when the latter saw how much ice was visible under the snow on Arrival Heights, he commented on the bad skiing. “Yeah, there’s a lot of bad skiing in Antarctica,” the Master replied, quite a historically relevant observation from someone with plenty of expert first-hand experience.

Bad skiing, but pretty.

If you look closely, just under the ‘horizon’ line at the base of the slope is a line of undulations that cross the image. These are the saw teeth of Glacier Tongue, the top of which forms the apparent horizon. You see, quite low!

The tip of Glacier Tongue, with Erebus snoozing behind and Weddell seals snoozing before.

The road took us around the tip; this was the closest I got, but it was close enough to see the height, and how the drifted snow to leeward would provide a ramp from which to climb onto the firmer ice. This was about as far south as the Terra Nova got, when scouting a location for the hut in January 1911, and they weighed up building the hut here vs. on solid ground at Cape Evans. The latter was considered the more sensible option, and rightly so, for only a couple of months later, the end of Glacier Tongue broke off in a big swell and floated out to sea!

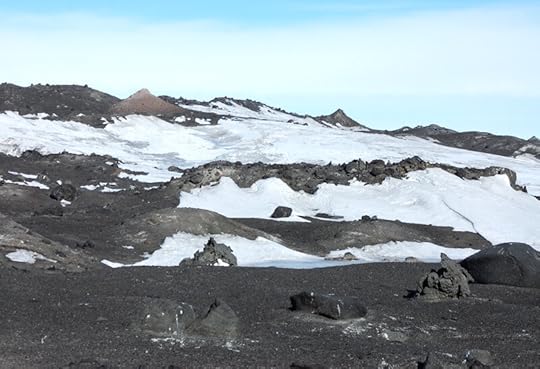

From here you get a million-dollar view of the ice falls down Erebus. Reading Cherry-Garrard’s description of them in Worst Journey, after seeing them in person, I have to give him full marks for descriptive power.

Here are the southern slopes of Erebus; but how different from those which you have lately seen. Northwards they fell in broad calm lines to a beautiful stately cliff which edged the sea. But here—all the epithets and all the adjectives which denote chaotic immensity could not adequately tell of them. Visualize a torrent ten miles long and twenty miles broad; imagine it falling over mountainous rocks and tumbling over itself in giant waves; imagine it arrested in the twinkling of an eye, frozen and white. Countless blizzards have swept their drifts over it, but have failed to hide it. And it continues to move. As you stand in the still cold air you may sometimes hear the silence broken by the sharp reports as the cold contracts it or its own weight splits it. Nature is tearing up that ice as human beings tear paper.

All the schemes for finding an overland route to Cape Evans had to contend with crossing these ice falls, and none could think of how to do it. So the sea ice it had to be.

I have been directing all your attention to the view to the right of us, but there are some interesting things to the left as well. Once we pass Glacier Tongue we are almost alongside Tent Island. I have no photos from this end of Tent Island because the road was horribly chewed up around here so all our concentration was on ploughing through, but here is one looking back at it.

I had never seen its resemblance to a tent, but Elaine prompted me to think of a circus tent rather than a camping tent, and yes, I can see it now.

Tent Island’s neighbour is Inaccessible Island, named for its steep slopes affording no access. I was surprised how big it was, something I struggled to capture on camera. Having spent many hours of my childhood on I-15, it reminded me of nothing so much as the top of a mountain in the Mojave, lopped off and stuck in the snow. Some of my photos from Cape Evans give a proper sense of scale, but seeing it end-on shows why it was called ‘inaccessible.’

This is also a good vantage point for Great and Little Razorback. They are aptly named: both are a straight and narrow with a very sharp ridgeline. Great Razorback is the larger of the two; Little Razorback is very wee indeed.

It’s called ‘Big Razorback’ on modern maps, but that sounds far less like a species of dragon.

While on the subject of scale, Erebus was always a problem. It never turned up as large in a photo as it seemed to be in real life. The trouble is, trying to get all of it in one shot, you have to zoom so far out that it is inevitably small in the frame. This is more what it felt like to be at the foot of Erebus:

We’re nearly there! I’ve seen an awful lot of the Barne Glacier as seen from Cape Evans; the pieces were in front of me now, and I knew that with only a little change in parallax, Cape Barne would slide behind the glacier face and then we’d be home.

Finally the road rounded a low promontory of blobby lava, and it came into view for the first time:

. . . And seeing it here, in its full setting, in 3D, I realised properly how this is just a shed in the middle of nowhere, and that, for all the stories it contains, it is so very very small, in a way I had never imagined.

But as I pulled up to the snowmobile parking area just offshore, it still felt like coming home.

February 15, 2020

Sea Ice: Crack Safety

Water ice is a curious material: though apparently a solid, it can nevertheless flow, bend, and wrinkle. The mile-thick Antarctic ice cap is very gradually flowing out to the edges of the continent, through the mountains in glaciers, and when those glaciers leave their channels they spread out like hot fudge (only much slower).

Most of the time, though, what ice does is crack. In a glacier this makes a crevasse; on sea ice, it’s a short trip into some very deep, very cold water. When you’re travelling across the sea ice, it’s the cracks you need to worry about, and once you start looking for them they are everywhere. This would be enough to put off a cautious traveller but most of them are relatively harmless: the requisite sea ice training helps you determine just how risky your movements are.

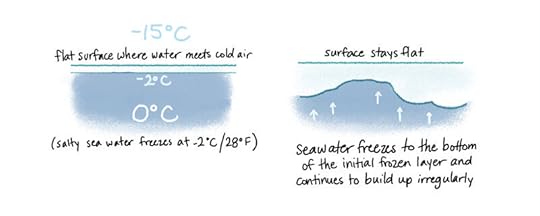

First, you have to learn about how sea ice forms. You will not be surprised to learn that this happens when liquid water meets cold air.

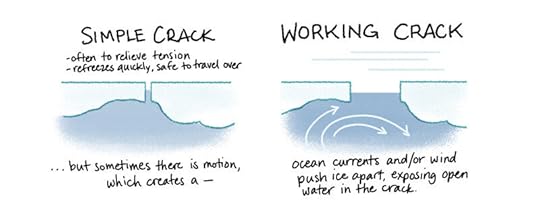

The nice flat young sea ice is never allowed to let be, though – forces in the water underneath and air above, or even changes in temperature, put strain on it, and to release the tension it cracks.

Like a broken bone, or a fault line in rock, once ice has broken it is more likely to break again at the same place, so being aware of cracks will show you where you ought to be extra careful. Simple cracks are usually one-time releases of stress, and once refrozen rarely pose a risk, but you need to be wary of working cracks because they have shown they are unstable and their condition might change without notice.

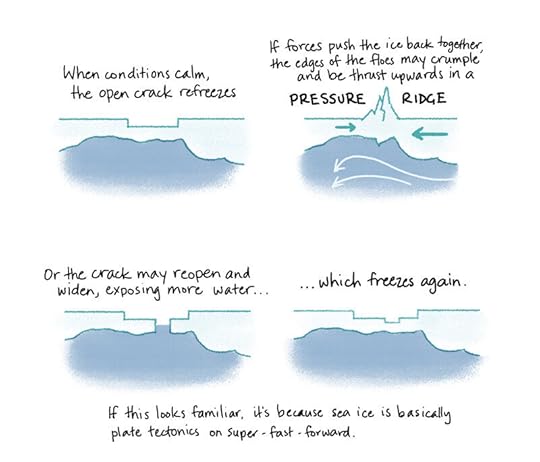

Because they are much larger, working cracks tend to be more visible, sometimes even when the sea ice has a layer of snow on it. Pressure ridges show up very well and are a useful indicator that the ice has been moving around. Here is a very small pressure ridge just off McMurdo Station:

The snow blowing across the sea ice has been caught and drifted by the protrusions of the pressure ridge. When you have an recessed working crack, instead of a pressured one, the crack gathers the snow and shows up that way.

When you come across one of these, you have to find out what is going on under there before you know it’s safe to cross, so the following procedure is taken:

Here is the crack you saw earlier, with its snow-covered secrets revealed.

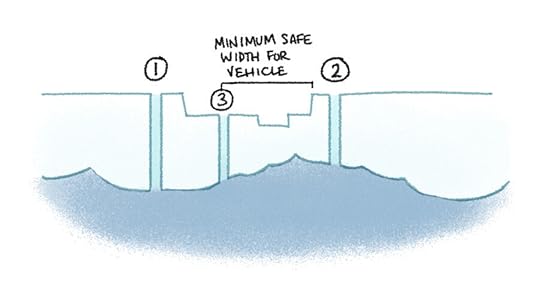

Each vehicle has different parameters for what a ‘safe’ crack is. Most tracked vehicles – snowmobiles, Hagglunds, etc – can safely cross a crack whose width is 1/3 the length of their track. So, if your snowmobile’s track is 90cm long, you can cross a 30cm crack even if it’s open water. (I would balk at doing it, myself, but it is theoretically safe.) You measure the maximum width of the crack to see if it’s within your vehicle’s safe crossing threshold. If it isn’t, it might still be safe to cross after all, but you will need to do some more measurements to find out.

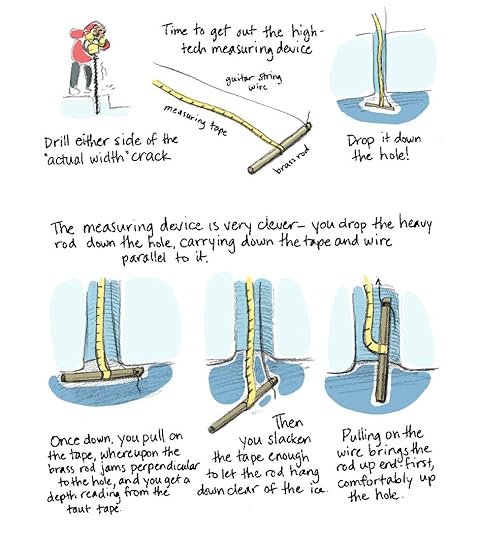

Measuring sea ice thickness is great because you get to use a) a power auger and b) my favourite device in the Antarctic toolkit.

You drill either side of the original crack to make sure the ice – which is weakest here, remember – is within the specified necessary thickness to support your vehicle. You don’t have to memorise this number because your teacher has given you a laminated card with a table of all the vehicles and their requisite ice thicknesses. Your job is not to lose the card.

Once you’ve ascertained that the ice either side of the widest crack is safe, you find a point within the safe crack width for your vehicle and measure the ice there. So, using the example from before, if your snowmobile with 90cm tracks comes up to a 45cm crack, you cannot cross, so you find a point 30cm (the safe width) from your side of the crack and measure the thickness of the ice there.

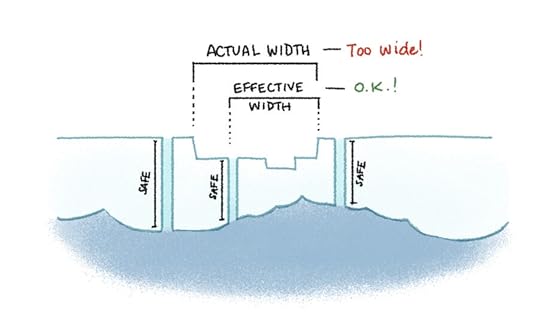

If the ice at the safe width is thick enough for your vehicle, then that becomes the effective width of the crack, and you can cross over. The actual width is the objective total width of the crack, whereas the effective width is the width that matters to you practically.

The reason you have to drill again at (3) instead of just subtracting the change in surface elevation from the measurement you took at (2) is because of the irregularity of the underside of the ice. You don’t know if there will be a big lump of nice solid ice there, or if it will be a surprisingly thin patch, so you have to check. For this same reason, you can’t measure a crack in one place and cross in another, because conditions along the crack can change completely in just a few metres.

Part of the job of the Sea Ice Master* at McMurdo is establishing ‘roads’ for vehicles to take to regular destinations (e.g. Cape Evans, the seal camp at Turtle Rock, Penguin Ranch, etc). Usually the ice is thick enough that these roads can go more or less directly there, but this year the ice formed so late, and in some cases was so choppy, that the roads snaked and dog-legged all over the place to find safe crossings. On top of that, the early summer had been exceptionally warm, and there was a great deal of nervousness around just how long the sea ice would be traversible at all. Luckily there was a cold spell just before I arrived, which bought enough time for me to travel to Cape Evans. In my last few days at McMurdo the sea ice did finally get closed to all traffic and the flags marking the roads were brought in, so it was a close run thing.

*not the actual job title, but should be

Sarah Airriess's Blog

- Sarah Airriess's profile

- 20 followers