Sarah Airriess's Blog, page 3

November 7, 2020

Pram Point Pressure Ridges

Scott Base, New Zealand's Antarctic outpost , is on a small cape on the other side of Observation Hill from the small American city that is McMurdo. It happens to be on a bay where the seasonal sea ice is trapped between the immovable object of the Hut Point Peninsula and the unstoppable force of the slowly advancing Ross Ice Shelf, so the ice gets pressed up in all sorts of interesting and dramatic ways there. During the part of the season that the sea ice is still safe for walking, there are regular tours of the pressure ridges from McMurdo, and I lucked into one in my first week, when a kind soul offered me his spot.

Shortly after arriving at McMurdo, my DSLR's autofocus stopped working. I had just met a camera crew who had arrived to shoot a documentary, and my minder made the very good point that I should go see if one of them might be able to fix it. They were keen to be helpful, but the solution was not immediately apparent, so one of them generously lent me one of his serious professional cameras for the excursion. So, these photos are what you get when an extremely middling photographer gets her hands on a weapon of great power, to capture information that might unlock the great secret of how ice interacts with light – in other words, there are a lot.

The tour set off, if I recall, around 8pm – well after dinner, and when the sun was low enough in the sky to set things off nicely. There was a clear walking route marked off that had been determined to be safe, and for the most part we stuck to that pretty closely. The main attraction was, of course, the pressure ridges that had thrust up and cracked, but as with any wave, there are also troughs, and these were where the real risks were. After the warm start to the summer, they had filled with meltwater, which would warm up in the sun and melt the ice under it. Similarly, if there was a crack in the ice where it had been pressed down, seawater would rise through it and fill the hollow. It was practically impossible to tell a freshwater surface melt pool from a saltwater upwelling pool, and either way the ice under them was likely to be less stable, so we were strongly discouraged from larking about in the puddles, however inviting they may be. (It was about -12°C when we were out, so that was not a temptation anyway.)

One of the first things I learned about sea ice is that if you see a seal, there is probably a crack nearby, and there were definitely seals.

When historical parties were camped at Hut Point, they used to come down here to hunt seals. It was nice to see them still sunbathing here

With the bright red parkas and the deep blue shadows, the other mammals in the area were pretty photogenic too.

Out here, also, was a phenomenon I was familiar with from reading. When one walks in fresh snow, the snow under one's feet compacts, then when the winds come and blow the fresh snow away, the compacted snow of the footprints is left elevated from the surrounding surface. Anything that stands up in Antarctica collects a snowdrift in time. I thought these were just sastrugi when I first crossed their path, until I looked closer.

Ice is a peculiar substance in that, while it is solid with a crystalline structure, it is slightly plastic. When it buckles, it will do expected things like break into slabs that pile up on each other, but given the right conditions, it can also bend, and the thin sea ice from the warm and windy winter just past was, in places, malleable enough to give the impression of walking on pie crust more than ice.

Aside from the low angle of the light and the hall-of-mirrors effect of angled snow surfaces bouncing photons off each other, there was intermittent thin shade from some patchy light clouds drifting overhead, which made for all sorts of interesting abstract studies.

I don't know what was going on there with the ice blocks, but it made me think of Nelson's marine biology ice hole, from which he'd have to hack a 'biscuit' of re-frozen ice every time he went out, and made a little wall of all these biscuits all around the hole.

When I tell people I'm doing a graphic novel set in Antarctica, they frequently laugh and say 'Well at least the backgrounds will be easy! ... White!' But as I hope the pictures above illustrate, it is a lot more complicated than that. As a certain junior geologist found out when trying to paint a scene from memory:

One of the amateur painters on that expedition once showed Wilson a snow scene which he had just painted in which the snow was mostly a dead white. Wilson said, 'Is that what you really saw, white snow? It's very rare, you know.' There was an argument round the table and at last Wilson said, 'Let's go and have a look at it,' and took his friend outside. They talked for a while and on going in again, the friend told the others, 'Blow me if Bill isn't right, it's gone pinkish since I painted it.' (Frank Debenham, Antarctica, p.200)

October 24, 2020

Castle Rock

There are a number of hiking and skiing trails around McMurdo Station. Some, like the Arrival Heights track, one can do alone and without giving notice; others, like the Castle Rock Loop, go far enough from the station and through questionable enough terrain that one has to check out, travel with a partner, and take radios in case of emergency.

I have become a great fan of the country walk in the UK. You dive into a beautiful morning on a promising footpath, refuel at a pub, keep walking all afternoon, maybe a quick half at another pub, then fall into bed all topped up on nature and exercise endorphins. Having been shuttled nearly everywhere in Antarctica via a motor vehicle of some sort, I was desperate to stretch my legs and cover some of Antarctica myself. I wanted to visit Castle Rock anyway, and the trip there and back was about the length of a leisurely country walk back home, so it was a natural thing to do once all my planned trips were over. My coordinator's opposite number is an avid hiker so he and I set out one sunny morning to put some miles on our sturdy boots.

The track is scenic and adventurous without being too arduous, so the Castle Rock Loop is a popular hike for the locals, as you can tell by the well-trammelled path in the photo above. Its full extent loops down to Scott Base and around back to McMurdo, but the shoreline down there didn't hold much interest and I'd done the route between Scott Base and McMurdo loads of times, so we just walked to Castle Rock and back.

It was a beautiful day. Much like the day I went up to Arrival Heights, it was calm, sunny, and hovering around freezing, the sort of conditions I insisted on calling 'picnic weather' long after the joke wore off. We also had an amazing low layer of thin cloud, which I unromantically call 'pond scum clouds' in my head, rather an unfair name as not only are they sometimes iridescent but they create wonderful light effects on the ground beneath them. On this day they were penned against Ross Island and cast their dappled shadows over Windless Bight, thereby showing up the perspective and giving everything the suggestion of being underwater.

In far worse conditions, Wilson, Bowers, and Cherry-Garrard walked across this view in June and July, 1911.

Away from Ross Island the sky was clear, and from up here on the spine of the peninsula you could see pretty much everything, including Williams Field, where I'd spent so much time recently:

There's nothing like a pure white background to show you how much pollution our internal combustion engines spew out – that smoke plume is, I believe, from a C-130 which was warming up to take off that day. It's a lot better than coal, but we've got a long way to go yet.

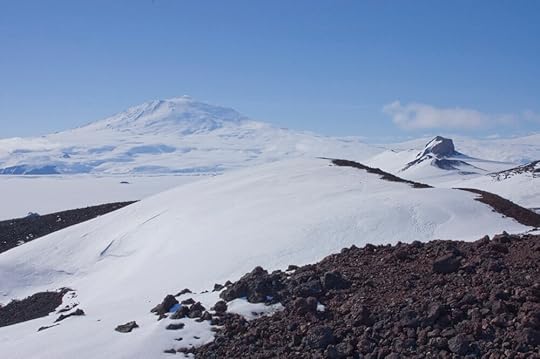

Humans' rudimentary flying machines are not the only thing to have emitted noxious gases into the Antarctic atmosphere. Mt Erebus still puffs away with the occasional mild eruption, but the Hut Point Peninsula is an artefact of a more active volcanic past. Much of the rock is obviously igneous, black or grey and spongy with bubbles, and most of the hills that stand up from the body of the peninsula are old volcanic craters, which spewed that aerated rock in ages past. Castle Rock is similar in origin, but gets its distinctive shape from having been an sub-glacial volcano, rather than a surface cinder cone. It's not exactly a volcanic plug, like the Devil's Tower in Wyoming, where the central chamber of a volcano solidified into a tower of basalt and the softer layers on the outside eroded away. Rather it is the volcano, having melted its way up through thick ice, which held its sides almost vertical while new layers of lava were deposited on top. This stratification, as well as the way the igneous rock has weathered orange-brown, makes it look more like sandstone than basalt to the casual observer, especially one who's spent so much time in the parks of southern Utah.

It feels enormous when you're standing under it – the name 'Castle Rock' is well-deserved – but when compared to other sub-glacial volcanoes (for instance Tuya Butte) it is but a teeny tiny fairy volcano.

This southeast face is the most precipitous; the north side slopes more and there is a climbing trail up it, should one wish to scramble a bit. It was just on the verge of opening for use when we visited, so we didn't climb. We did take as many pictures as we could, staying on marked paths, but before long it was time to turn around and head back again.

We stopped at a small shelter we'd passed on the way up, which you can just see as a little red blob in the photo above. It is officially known as an Apple , but some refer to it as a Tomato, which it more closely resembles if you ask me. It's an emergency shelter, in case you happen to be doing the Castle Rock Loop when a blizzard blows up, and it is actually rather cosy inside.

Further along the trail, the familiar landmarks of McMurdo rose into view.

That's Observation Hill on the left, and Arrival Heights on the right, with the "Golf Ball" under Mt Discovery in the middle.

As you may be able to guess from the above photo, the slope dips more steeply as we approach the base, and because of this it catches the afternoon and evening sun, and gets very icy. We both had good hiking boots but not crampons, so on the way up had tried to climb by the snowier sections. I was looking forward to sliding down on my coat on the return journey but alas it wasn't quite steep or slippery enough for that – the best I could manage was a slow bum-scoot, which was fun but not exactly efficient. However, it got me close to some funny features I'd noticed on the way up.

The whole slope was dotted with these spots of clearer ice, many with a chrysanthemum-like crystal structure. What was going on here? What were these things?

My guide explained that they form when a rock gets blown onto the slope. Being dark, it absorbs a lot more heat from the sun than the surrounding ice does, and so melts its way down through the ice, and keeps going as long as it the sunlight can reach it. When the ice refreezes to fill the hole, it reorganises its crystalline structure from the chaotic granules left over from when it was snow, to something that reflects the container in which it was formed. You can sometimes see this radial pattern in your ice cube tray – this is exactly the same thing.

We had been walking on ice and snow all day, which made for a surprise when I stepped back onto the familiar gravel of McMurdo. I have walked on a lot of snow in my life but I suppose I always went from frozen water to frozen ground or pavement. I have not, apparently, stepped from ice to fine gravel so dry that the pebbles haven't frozen together, and my first impression on doing so was that I had stepped onto cake. It was a very strange sensation that took some minutes to shake, but I can remember it even now.

It had been a very good thing to stretch my legs, and getting out in the fresh(er) air with a walking partner who could make good conversation but also didn't mind silence did me some good, to process the whirlwind of trips I'd made in such a short time. In that sense, my own walk to Castle Rock was much in keeping with those who made the hike when waiting for the sea ice to freeze over in 1911 – it was somewhere to go that was well away from the madding crowd in the Discovery Hut, where one could have a private conversation or just catch a bit of peace and quiet. On its busier days, the route is well-enough travelled that one stands the risk of encountering as many people out there as anywhere else, but we got a quiet weekday when everyone else was working. Being a bright day in midsummer, my imagination will have to add the richer hues of the dying light of autumn, but I'm glad I got to stand there in person at least.

If you want more detailed, expert analysis of the geology of Castle Rock, this is the PDF for you.

October 10, 2020

Arrival Heights: The Forbidden Zone

You saw my midnight hike up Arrival Heights some time ago. What I failed to disclose in that entry is that I didn't go all the way up to the bit specifically known as Arrival Heights, in part because it was midnight but also because a great deal of it is within an ASPA (Antarctic Specially Protected Area). The historic huts and Cape Crozier are also ASPAs. I had applied for and received the permit to visit them with authorised personnel, but my coordinator had suggested I put Arrival Heights on the list as well, so I had permission to go there, too. The authorised personnel in this case was in the office right next to mine, but it wasn't until fairly late in my visit that our schedules and the weather aligned for me to go up there with her. However, it turned out to be a spectacular day, and fortuitous timing as it turned out – but I will get to that later.

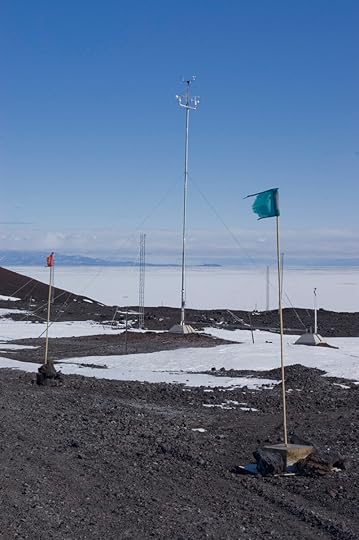

Shelley, my native guide, is Keeper of the Antennae, and Arrival Heights is all antennae – that's why it's Specially Protected; with guy wires and exposed wiring everywhere people could get into all sorts of trouble by accident, plus one isn't supposed to get near the sensitive equipment with certain types of insensitive equipment, lest one interfere with the results. Our first stop of the day was actually in the opposite direction: Between McMurdo Station and Scott Base is an array of antennae rigged to detect meteors entering Earth's atmosphere. It's a project of the University of Colorado, Boulder, and the extra fun thing is that you can follow the data coming in live from the comfort of your own home: https://ccar.colorado.edu/meteors/meteors

Shelley, Keeper of the Antennae, was in charge of this site too, and she had received a notification shortly before heading out which demanded she solve a problem in person, so that is where we went first.

The computers that process the information from the antenna array live in this little hut. That's Observation Hill in the background – we're on the other side from McMurdo here – with the Scott Base road marked by the orange bollard at upper right.

Here's Shelley about to load the UCB website to make sure everything's running OK:

(It amused me to see such a run-of-the-mill desktop setup in such an exotic locale)

And here’s the processing unit:

The reason she'd been called out was not anything exciting like an emergency antenna repair or technology problem, but rather that the hut was getting too hot. Like any shed in a sunny garden, on a clear calm day it collects heat, and the computers don't like that. The research budget did not extend to installing an automatic climate control system, but did stretch to pinging Shelley to come over and wedge a roof hatch open with a block of wood.

Job done! (I'm telling you, the Trucker's Hitch is the knot to know.)

Temperature moderated, we retraced our steps to McMurdo and then took the access road up to Arrival Heights, where Shelley was due to do her weekly inspection of the antenna in Second Crater.

As I said, there are a lot of antennae up in the ASPA, and both the US Antarctic Program and Antarctica New Zealand use the site for their research. So, naturally, they each have a hut up there. Here is the Kiwi one, in their signature green:

The US hut was on the other side of the car park, with its signature Ford F-150:

The two countries' choice of vehicle was amusingly symbolic of their respective cultures but is, perhaps, a post for another day. We've got antennae to tend, here!

Actually, the nearest one is a weather station, but you get the idea.

First, another nip into the hut to check everything was OK.

This hut had quite a few more computers than the last:

Plus a workbench with all sorts of doodads for repair and whatnot.

And, if you were waylaid by a blizzard (being up high, one is more exposed, and the weather could often differ substantially from what was happening at base), there was a comfortable place to have a little nap.

The reason I had been encouraged to go up to the Arrival Heights ASPA was because it afforded excellent views of the whole McMurdo Sound. It was also a site of historic interest as the Terra Nova men returning from the Depot Journey would come up here from Hut Point to check whether the sea ice had frozen between them and home base at Cape Evans. There is a marginally better view from Castle Rock, which they visited occasionally, but Arrival Heights was much closer. It's still a good hike from Hut Point, though, so accounts that make it sound like a short stroll are to be taken with a grain of salt.

Second Crater (above) is a hill on top of the heights which had, once upon a time, been a volcanic cone. That is long past, though, and now it serves mainly to provide a sheltered alcove for a very sensitive radio antenna. While Shelley did whatever antenna tending needed to be done, I climbed to the top of Second Crater and took photos.

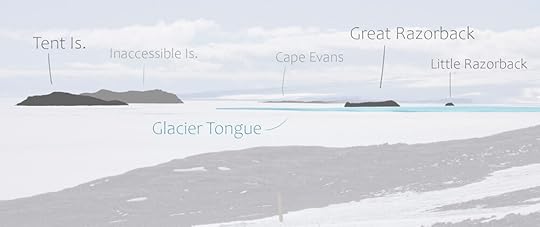

First, the all-important view to Cape Evans. From this altitude one gets a better view down to the bays, to see just how much ice had formed – and one can just see over Glacier Tongue, to tell whether the ice is in on the other side, which certainly can't be done from Hut Point.

In 1911, the end of Glacier Tongue had broken off and floated away, so it would have been an even clearer view.

McMurdo Station's situation at the base of the Hut Point Peninsula means that massive Mt Erebus, which dominates the landscape, is blocked from view by the hills close to base. Up here, one got a proper sense of how the geography all fitted together.

Looking up the spine of the peninsula: That's one of the peaks of Second Crater in the foreground, Castle Rock being all castle-y to the right, and of course our good friend Erebus looming in the distance.

In the other direction, we were even higher than Observation Hill, so you can get a good sense of the whole south end of McMurdo Sound. From left to right: Crater Hill (foreground), White Island (background), The Gap and Observation Hill (FG), Minna Bluff (very faint BG above Ob Hill) and Black Island (BG). You can see how icy the snow is up here, which encouraged some care in moving about.

The different shades of volcanic rock on the Hut Point Peninsula had surprised me, and something about the light or the angle up here made them show up better on film, so here is a closer shot where you can see a bit better. Just off the shoulder of Observation Hill there is some faint scarring in the ice …

… That is Phoenix Airfield, the landing strip for the big planes, and while Shelley and I were up there, a C-17 came in.

While Shelley was occupied in the hut and I was watching the big plane, someone turned up at the Kiwi hut in that Toyota you saw above. She turned out to be Shelley's ANZ counterpart, and asked if I might lend a hand bringing a canister of liquid nitrogen into the hut. Never in my wildest dreams had I anticipated helping with liquid nitrogen, so of course I said yes. In the course of the enterprise, she ascertained that I was the visiting artist who had worked at Disney, and she commented on how cool that was; I replied that I never got to haul liquid nitrogen around at Disney! She invited me to come give a talk at Scott Base, which felt like getting the Golden Ticket – aside from the limited 'open hours' when Americans are allowed to visit, Scott Base is invitation-only, and now I had an invitation!

Before long, Shelley was ready to go, so we trundled back down the hill to base. I had a camera full of photos to sort, and another presentation to put together ...

September 26, 2020

Temperatures

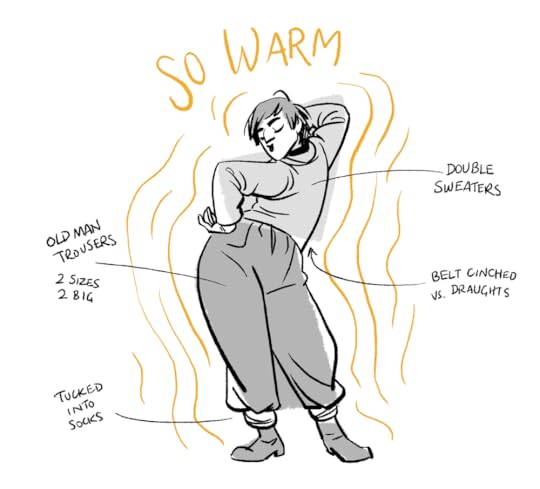

It’s all well and good to share photos of Antarctica – after all, it is a beautiful place, and we are predominantly a visual species. The photos can give you a sense of what it looks like, but not what it feels like. If people know anything about Antarctica, it’s that it’s cold. But how cold? And what kind of cold?

I cannot speak to the full range of Antarctic weather. I was down for exactly a month, in early summer, and aside from the first week, the weather was unusually calm and mild. To my great disappointment, I didn't see a single blizzard! But I did get enough to compare the feel of Antarctica with other places I have been, and I hope that by making those comparisons here, I will bring you a little closer to understanding quite literally what it feels like to be there.

Temperatures are misleading. A number can only give you an impression of what one might actually feel when one steps out the door. Humidity, sunshine, and wind are external factors that affect the perception of temperature; this can be further influenced by how much sleep or food you've had, BMI, resting metabolism, your accustomed climate, where you've just come from – so, 6°C can feel different from one day to the next, or to two different people standing side by side.

There are roughly two types of cold: dry and damp. The influential factor is water, because it takes a tremendous amount of energy to make water change temperature – this is why it takes so much power to boil a kettle, and why we bring hot water bottles to bed instead of hot gravel bottles. In dry environments, there is less water vapour in the air to suck up the heat coming off your body, so you get to keep more of it for yourself. It may be well below freezing, but you will feel the cold merely as a sensation on your skin, where it meets the air, and not something that goes right through you. Damp cold, because of the energy-hungry water in the air, feels a lot colder. It’s not enough merely to cover your skin, you need layers of fabrics that have moisture-repelling properties (wool is key; cotton is useless). Your precious body heat will leak out through any weak point in your clothing. Because of their different properties, dry air can be much colder than damp air and yet feel more comfortable. In my experience, damp cold is the worst when it’s above freezing, because below freezing the air can’t hold so much water. Damp climates, however, tend not to get much below freezing, so when people from damp climates imagine very cold temperatures, they imagine the insidious cold they know, only much much worse. It’s not necessarily like that.

Even the objective numerical value of a temperature presents a problem: my historical sources, and the United States of America, report temperatures in Fahrenheit, while the rest of the world operates in Celsius. Scientists prefer the metric system, but McMurdo is an American base, so it's functionally bilingual. I tend to think in Celsius, but as the historical record was in °F and I wanted to be able to compare what I was experiencing with what my guys experienced, I paid more attention to °F while I was down there. In this post, I will report actual temperatures in both, so you can look at whichever one you understand best.

When I left Britain in mid-October, we had been having a very mild autumn, after a hot summer. My hopes for hardening up a little on the way to Antarctica were dashed when Vancouver, though objectively colder, felt merely fresh and delightful, I assume because it was unseasonably dry. LA is always dry in the autumn and usually hot, so that was no surprise; Christchurch however was much warmer than expected, and because it wasn't as dry as LA, felt even hotter. After several days' delay there, I feared my blood was much too thin to be hurtled into ice and snow.

It is regulation to wear one's Extreme Cold Weather gear on the plane to McMurdo. Aware that I'd just had a fortnight of heat to thin my blood, and that they were just coming out of a cold snap down there, I was only too happy to take this precaution. When the plane landed, everyone piled on their balaclavas and tuques, and when the door opened, an icy-looking fog formed as our pent-up breaths met the cold air from outside. Here we go, I thought. As I approached the gangway I braced myself for the smart of cold air on exposed skin and the stiletto keenness as I inhaled, but . . .

. . . it was fine.

In fact, it was so fine that when I was allowed to change out of my ECW, I put on my street shoes, not even my cold-weather hiking boots. I knew dry cold from Utah and Alberta, but I was coming to understand that in an Antarctic context, “well it was -20, but it was a dry cold” isn't a joke, it's just a statement of fact. +6°C(42°F) would be miserable in damp Cambridge, but -6°C(21°F) was quite comfortable at McMurdo – if it wasn't windy, one could happily go about without a coat.

One always had a coat to hand, though, because the wind could turn up at any time, and it made a big difference. The first time I went to Cape Evans it was so mild as to be balmy – I was in snow pants because they were required for the snowmobile, but on top I stripped down to just my base layer and a medium-weight sweater, and was even a bit warm in that. It was -1°C/30°F, but I could happily have sat down to a picnic.

Before we left, I wanted to make a quick trip up Wind Vane Hill. I got hot climbing it, but while on top, a breeze kicked up, and before long I was wishing I hadn't left my jacket at the bottom. The reason I have my hands tucked in my snow pants bib in the above photo is because they were beginning to feel quite nippy. I always had a jacket with me after that, even if I cursed its dead weight the whole time. (It was usually my trenchcoat, not the big red parka, for this reason. I will go into more depth on clothing in a future post.)

A similar thing happened on my Basler flight. I'm afraid I don't know the actual temperatures where and when we landed – we were at the inland extremity of the Barrier, though, so everything I'd read told me it ought to be noticeably colder than McMurdo. It might well have been. But the only clue that it wasn't a perfectly warm summer day was that the slightest stir in the air breathed ice on my hands. It felt much the same at the much higher altitude site of CTAM. The interior of the continent is even drier than the coast: apparently, in the absence of wind and on a bright sunny day, this makes temperature barely perceptible at all.

A windless day is a vast exception in the case of Antarctic weather, though, and besides chilling a human body, the direction of the wind makes a big difference to the objective air temperature. A north wind, arriving from over the open sea, was comparatively mild. Most of the time, however, the wind was from the east to south, coming cold off the icy interior. This sends it funnelling through The Gap straight at Hut Point. The Hut Point Wind was infamous in the Heroic Age; even now it can be a pleasant day at the station, but one must remember to kit up just to walk around the corner to the Discovery Hut.

It did make for some great photos, though, because if the conditions were just right – which they were a few times in my month there – the wind would kick up some freshly fallen snow and things would look so very Antarctic. The funny thing was, on the days when it looked quintessentially polar, it was actually comparatively warm. The snow was so powdery that a fairly light wind could lift it, so it didn't have to be brutally windy to look brutally windy. The cold really sets in when a high pressure system stays in place for a while and keeps the air still; if there is turbulence, there is warmth, and if a weather system moves through – such as the kind that delivers snow – the temperature rises considerably. So in order for there to be fresh snow to blow around, there will have been a recent warm spell, whereas if it's starting to get cold again, the new snow will have compacted enough not to blow around. The strongest winds I encountered in Antarctica were at Cape Crozier, but you'd never guess it from my photos, which haven't a speck of drift. I am sure there are exceptions to this, but this was a dependable pattern in my time there.

Quite a nice day, really.

Don't be alarmed, it's just an inch of fresh powder suddenly blowing off, like flour from a baker's table.

On the other hand, you're looking at a 35 mph wind, here. See it?

One of my oddest temperature memories was in one of those balmy drifty situations. I had been asked to give my history lecture over at Scott Base, and I was to wait for the Kiwi truck at a designated pickup point on the road coming over from The Gap. There are three official categories for weather in Antarctica: Condition 3 is when everything can operate as normal: it can be cold, it can be windy, but visibility is fine and the ordinary precautions will see you through. Condition 2 is when things are starting to get serious: drift and/or winds are reaching dangerous levels, extra precaution is necessary, and venturing outside is discouraged. Condition 1 is when everyone is required to stay indoors except on vital business as merely venturing outside is a life-threatening risk. During my month there it was always Condition 3, but within the hour of my pickup a Condition 2 had been declared on the Scott Base side of The Gap. My ride said she would be coming anyway, as she would be overwintering and needed the practice of driving in Condition 2, so I went up to meet her. I was hoping I would finally get a blast of Antarctica, but it gave me a surprise. For one, it was warm. And, yes, it was windy, but not desperately so, and the wind had a damp sweetness that, weirdly, made me think of swelling streams and crocuses. The Condition 2 had been called purely because of the drift, which was obscuring the road and therefore made driving more hazardous than usual. It was surreal to hear my driver checking in with her radio operator as if she were chasing tornadoes when it was really quite pleasant out.

My first few days at McMurdo were by far the coldest of my whole visit. When I first visited the Discovery Hut it was -18°C, or just below 0°F, and rather windy on the way back. That was when I learned that one can be feeling really quite cosy all over but one's outermost extremities can still suffer the cold – I distinctly remember wondering why my fingertips were tingling when I felt so warm, and a little while later my toes went numb and I had to stamp them back to life. The dryness, not sapping your core heat, can lure you into a false sense of security, and nab your digits while you're not looking.

After that, daily highs mostly hovered around the freezing point, and lows rarely dipped as low as -10°C/+14°F. This was really very mild – indeed, the people who'd been down since September could often be seen flitting about in t-shirts – and was an amusing irony for me personally. Twice in the past I'd visited Calgary in search of 'Antarctic' cold and hit, instead, a relatively mild spell; it turned out that in Antarctica I was getting exactly the same weather that I had thought un-Antarctic in Calgary. Not only was it the same weather on paper, but it felt exactly the same as well – the light, fresh kiss of frosty air on one's cheeks, surprising warmth in the sunshine but a breeze to keep you honest, and even the same granular texture to old snow. Altitude can give you the same feeling, as the thinner air cannot hold as much moisture as it can at lower levels, so if you've not been to the Prairies but have been on a ski holiday, you can use that as a reference point as well.

It is much harder to draw parallels with damper climates. At home in Cambridge, I have a sort of 'misery zone' between 4°-10°C (40°-50°F) where it's too cold to be warm, but not cold enough to be crisp, and the damp seems to seep through every layer to reach in and chill. As the thermometer plunges towards freezing and below, it is, ironically, more comfortable weather, because the colder the air is, the less moisture it can hold. In Britain I have sometimes found myself taking off layers as the mercury falls. When imagining Antarctica, people often extrapolate from their own experience of cold temperatures: If your base measure of cold is the 'misery zone' in a damp climate, such as Europe or the Eastern US, then you may think 'If 6°C feels like this, then -6° must feel that much worse' when in fact all the other factors at play can make it preferable. Even the cold days on my arrival at McMurdo were nicer, experientially, than a misty morning in deepest February back home. At one point, Cherry describes Antarctic summer weather as resembling a crisp sunny morning in September, and indeed from a British perspective Antarctica often felt more like a bright and breezy 13°C (55°F) than anything closer to freezing.

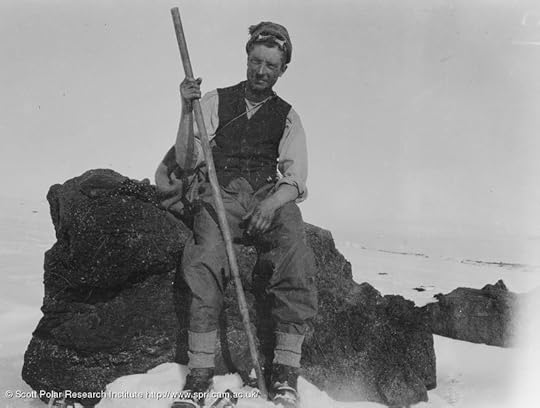

Bernard Day in perfectly comfortable garb for a summer's day on Cape Evans.

This gave me some perspective on the early explorers. If they had spent their lives on this chilly island, and then travelled to Antarctica over a chilly sea, they would be coming at it with all the assumptions one acquires from experience with humid cold. Finding not an amplification of your worst experiences, but instead a wonderland where the thermometer seemed to exist in a different reality – certainly the case when they arrived in midsummer – would encourage some overconfidence that we might consider reckless. Some, like Scott, had been down before and knew how deceptive the weather could be; his journals are full of chiding his team for not taking Antarctica seriously. But there were many who were new to it, and even after an Antarctic winter, sheltered as they were in an insulated hut by the sea, they did not fully grasp how dangerous things could get inland and how narrow the margins were. A breeze may be thrilling when it brings the truth of -10 to exposed skin warmed by the sun; when the truth is -40 it's instant frostbite. While I didn't get temperatures that low, my experience with higher ones can, I hope, help me imagine how that would go.

The dryness that made the cold so bearable granted me a reprieve from an opposing worry. Outside of Britain I generally find buildings overheated in the winter – I have to remind myself to pack light 'inside clothes' or else I suffocate. This is especially the case in the States, and McMurdo being an American base I foresaw having to strip five layers off and put them back on again every time I entered or exited a building. They may have been overheated, but I don't know – dry air saps the potency of heat as well as cold, so it was as comfortable to wear three layers as one, and that saved me a lot of time in the cloakroom. Thanks, Antarctica!

I had got so used to the nip in the air that I thought I'd be inured to cold for the rest of the winter, but once I was back on this cold damp North Atlantic island, the misery zone was as potent as ever. I may not have picked up thermoregulation superpowers in Antarctica, but I did come back with two secret weapons: merino wool base layers, and an utter disregard for my appearance so long as I was warm. I highly recommend both to anyone in a disagreeable climate.

September 12, 2020

McMurdo Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving is one of the most important holidays in the US, so it is an important day on the McMurdo calendar as well. In civilisation, it’s usually celebrated with big family gatherings on the last Thursday of November, making for a four-day weekend typically filled with football and Christmas shopping. At McMurdo there is so much that needs to be done in such limiting circumstances that a six-day, 60-hour work week is standard; taking three whole days out of the peak season would be unconscionably profligate, so instead they celebrate Thanksgiving on the following Saturday and luxuriate in a rare two-day weekend.

Growing up hundreds of miles from extended family, and being a fan of neither football nor shopping, the primacy of the holiday had mostly passed me by; in the years I was an adult in the States, I usually spent it with other ‘Thanksgiving orphans’ doing something atypical. Perhaps the most important Thanksgiving of those years was the one I spent in New York on the promotional gig for Princess and the Frog, because that’s where this adventure started. I was working that day, but they catered a turkey dinner for us at the venue, and I ate my roast and sweet potato off a paper plate backstage while reading The Worst Journey in the World for the first time. Exactly ten Thanksgivings later I was in Antarctica, where it all took place.

The early expeditions knew the importance of good food. Obviously as a source of energy, getting sufficient calories was a prime concern, but when one is starved of most of the pleasures of life, food takes on a great emotional significance as well as biological. The cook on the Discovery Expedition was so bad he was sent home when the relief ships came. Both Scott and Shackleton learned from this experience – Shackleton brought a wide variety of ‘luxury’ foods on the Nimrod Expedition, and Scott made sure that the cook on the Terra Nova could turn his hand to making ordinary meals delicious and extraordinary foodstuffs palatable.

The biggest event in the Heroic Age culinary calendar was the Midwinter Feast, which took on the significance of Christmas, for not dissimilar reasons of brightening the darkness and cold. At Cape Evans, Midwinter 1911 began with a multi-course meal replete with sweets and alcohol, followed by toasts and the presentation of an ersatz Christmas tree bedecked with amusing little presents for everyone, and finally the table was collapsed and cleared away for a slideshow and a dance. Cherry-Garrard declared “It was a magnificent bust.”

American Thanksgiving falls during the Antarctic summer, so unlike the Midwinter feasts of yore, a lot of the activities are outdoors, and involve the New Zealanders from around the corner at Scott Base as well. There is a manhauling race (which the Kiwis always win) and a foot race called The Turkey Trot, which runs a loop around Cape Armitage and back through The Gap. Costumes are not compulsory but have come to be expected, so I went to take photos.

A runner arrives

The rainbow assembles – the figure centre-right with the splayed legs is wearing a turkey costume.

And they’re off!

Some of the first successful returnees

Being an open day, there was an uptick in tourism from the New Zealand side as well:

McMurdo’s mighty kitchen crew, with extra volunteer labour, had been working to prepare the feast all week. There were a number of scheduled seatings throughout the day, to regulate flow and make sure everyone had a table. I met with my coordinator’s other ducklings outside the Galley at 4.30 for the 5.00 seating, and when we were allowed in we got to see how the rather utilitarian Galley had been done up as a nice buffet, with tablecloths and everything.

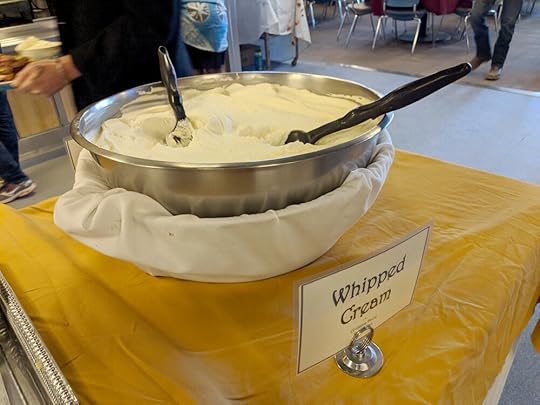

I was particularly amused by this offering, given that Capt. Scott’s great food craving from the southern journey on the Discovery Expedition was a great big bowl of Devonshire cream:

It was actually cream, none of that Whipped Topping stuff.

We found our seats and tucked in. Most of my tablemates were British and it was their first experience with some American Thanksgiving standards – the pecan pie in particular got an enthusiastic vote of confidence.

You can’t see it in this photo, but the group behind us, to the right of the frame, had had some orange trays made (vs the Galley’s usual blue) that read ‘Make Antarctica Great Again.’ As far as anyone could tell, they were not being ironic. In a community dedicated to science, where even the dishwashers are likely to have a university degree, there is a certain amount of tension under the current US administration. Government support makes McMurdo possible, but the anti-science, anti-conservation tilt of The Powers That Be render it precarious, and the MAGA crowd at Thanksgiving were the subject of much anxious whispering over the next few days.

Exuberant after-dinner larks are as much a feature of Antarctica now as they were a hundred years ago, only with the advantage of electricity they are now quite a lot louder. I am not one for crowds or noise, and had had quite an intense week, so my plan was to make for the dormitories before the impromptu nightclubs opened, but I did stop in to see the one my friends had been setting up. They were down to get some specific footage for a documentary series, but the weather had not been on their side, so to fill their days they had put a great deal of time and effort into converting the gym into a dance club. Regrettably I don’t have any photos of it, but they did a really outstanding job, and the verdict the next day was that Club 77° was the best venue in town.

For my own part, I was happy to hit the hay.

View from my dormitory window

If you’re curious about what goes into feeding Antarcticans, PBS’ Nova did a great little feature on it here:

And yes, the pizza really is that good.

August 29, 2020

Views From Crary

Thanks to the cost centre allocations of the National Science Foundation, being an artist in Antarctica made me, officially at least, a science grantee. This meant I got ‘lab space’ (i.e. a desk) in the Crary Lab, a three-tier purpose-built science centre at the heart of McMurdo Station, whose library, on the upper floor of the main building, had panoramic windows overlooking the whole of McMurdo Sound.

My own workspace was in a windowless room which turned out to be one of the most reliably dark places in the land of the midnight sun. Being just off the main library room, every time I came or went I got an eyeful of that amazing view. It was not short of cognitive dissonance: the building was strongly reminiscent of the late-80s built-in-a-hurry school buildings where I’d spent most of my very prosaic childhood, yet the windows looked out on a view that was not only heavenly but seemingly teleported from Ponting’s century-old photos. It was two breeds of familiarity clashing heavily together.

I took a lot of photos from these windows, as I was here nearly every day, and I’d usually be leaving for the dorms around 10 PM when the light was particularly nice. So it is a photo post for you today, almost all of these taken from the Crary Library, though some were from the overlook behind the dorms, where I’d spend a few minutes on my way to bed if it was a particularly beautiful evening.

Something about McMurdo Sound attracted and held cloudcover; frequently one could see clear skies to the north and/or south, but be in shadow oneself. I particularly liked night where the sun, on its circuit, was behind the Western Mountains, making them stand out in silhouette and doing nice things with blue and orange.

Sometimes icy patches on distant glaciers would catch the light.

Out on the ice was a field biology camp known as ‘Penguin Ranch,’ run by two scientists from Scripps Institute of Oceanography, studying Emperor penguins. Those are full one-storey-tall portable sheds out there, not tents.

Mt Discovery was never dull; here it is with a rolling blanket of fog(?) – I kept expecting this to come in, but it was held almost in stasis behind the mountains.

For about three days Mt Discovery was hidden behind a very localised weather system, and came out with its stripes of exposed rock completely buried in a thick layer of snow. The same thing happened to the Southern Journey at the foot of the Beardmore in December 1911, when at the same time Amundsen was sailing through calm sunny weather.

Looking over the roofs of the Crary Lab and the MacOps building to Hut Point and Vince’s Cross, familiar from Wilson’s paintings. There were times I felt bizarrely like I’d time-travelled to the future, and this view often brought that feeling on.

One constant from the Heroic Age to Now is that everyone keeps an eye on Minna Bluff, because it is one of the most reliable weather forecasts in a notoriously unpredictable climate. If you can see Minna Bluff, the weather will remain good. If you can’t …

… then a blizzard is probably on its way, and you need to get to safety as quickly as you can. There is sometimes an intermediate stage, where Minna Bluff ‘has its cap on’, which suggests a change is imminent, but we had such idyllic weather during my stay that I never caught that one.

Some times, one couldn’t see anything at all.

These conditions still had an appeal, in a more abstract way.

When the clouds broke up, a whole new array of light effects arrived.

The sun spinning around the sky and the ever-changing sky and ice conditions made the Crary windows a landscape kaleidoscope – no two days were the same; often two consecutive hours would be substantially different. I certainly never got tired of the view, even on socked-in days. One day, when it was snowing quite heavily, the only differentiation I could see between surface and sky was a faint turquoise tinge in the sea ice – something about the diffuse light brought out only the refraction through the ice and nothing else. As a painting it would be the most obscure abstract expressionism, but in person it was almost mystical.

Good night, Pisten Bully!

August 15, 2020

Basler to the Beardmore 4: And Back Again

Having had the grand tour of the Beardmore Glacier, we set our course to return to McMurdo. There was one waypoint we were to hit on the way back, but the first part of the journey was just peaceful ice and cloud as far as the eye could see.

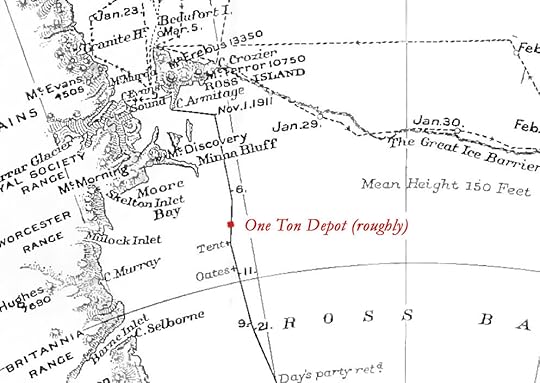

After about an hour of abstract land- and skyscapes, we approached our rendezvous point with history: 79°29'S 170°E – One Ton Depot. There it is!

One Ton Depot was the name given to the final cache of food and supplies taken out along the route to the pole in the summer of 1911, so that not everything would have to be hauled from base when they set out to reach the South Pole the next summer. It was supposed to be laid at 80°S, but due to a spell of bad weather, the condition of the ponies, and the imminence of the end of the safe travel season, they decided that 79°29’S was far enough. In 1911 that was the prudent decision; they could not have known that, the following year, the last three survivors of the five who reached the Pole would get within that 35½ statute mile margin and could really have done with the extra food and fuel. It is one of the great ‘what if’s of polar history.

Another ‘what if’ hovers around Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s trip to One Ton in March 1912. In Scott’s plans, he called for the dog teams to meet the returning Polar Party out on the ice shelf. Due to extenuating circumstances at base, the dogs were sent out later than called for, and under the command of Apsley Cherry-Garrard, who had never been in a leadership position before and could not navigate with a sextant as the Navy men could. The Polar Party was reported to be in good condition by the last people who had seen them, and, time having passed since the planned rendezvous, were likely to be nearer One Ton than the original rendezvous, he was instructed to go there and then decide what to do.

Just as it had when the depot was originally laid, the weather was starting to break up – Antarctica moves very quickly from summer into winter, and it takes no prisoners. Cherry and the dogs arrived at One Ton on March 4th; over the following week only two days were clear enough to travel, and all were bitterly cold. The dogs were short of food and losing condition, so taking them further would have been a significant risk. On March 10th, Cherry left the extra rations and turned back north. Again, an apparently prudent decision at the time, but one that would haunt him for the rest of his life.

It was a completely unscouted location so we couldn't land, but we did a low tight turn so that I could see the terrain and, more importantly, what was visible on the horizon. I had heard that One Ton was the furthest south one could reliably navigate by landmarks alone – a convenient location for a young explorer who had failed to get his head around celestial navigation. The view would be different from a few hundred feet up than it would be from ground level, but with the clear day and calm conditions I could at least guess what might be seen. The impression I had was that the top of Erebus would just poke up from the horizon, there, but as far as I could tell from the plane, one was more likely to see Mt Discovery, which was closer and darker.

This is a fully zoomed-out view of Ross Island from that loop:

We were closer to Minna Bluff and Mt Discovery; the latter is a smaller mountain than Erebus, but being closer and with more exposed rock, the atmospheric perspective would not blot it out so much.

Mt Discovery is the peak on the left, and Minna Bluff is the dark ridge from centre to right.

This is not a fair photo to judge against the previous one for distance, as I have zoomed in here, but you can see how the contrast is much higher on these nearer landmarks. I think the only way you'd locate Erebus more easily than Mt Discovery from here is if there was enough of an eruption to make a large smoke plume.

When planning this trip with the fixed-wing coordinators, alternatives had been discussed in case the Basler flight didn't work out. I would get views of the Beardmore from a turnaround flight to Pole, and for a recce of One Ton might join one of the regular maintenance trips out to an automated weather station called Alexander Tall Tower, which is only 25km from the location of One Ton. All the automated weather stations have names, hence ‘Alexander’; 'Tall Tower' is because it's 30m high with instruments at regular intervals all the way up, to measure what's happening in different layers of air.

As it happened, the Basler trip came off, but we paid a visit to Tall Tower anyway – in fact we buzzed it: one of the other Kenn Borek planes was out there, having brought its attendant meteorologist plus one of the other media outfits, a film crew making the second series of One Strange Rock. This crew were my best friends at McMurdo so it was really fun to see them at work, not least because their luck with flights had been much poorer than mine.

A study in scale, Man vs Ice Shelf

Just as One Ton was on the 'Southern Road' in Scott's time, so Tall Tower is on the Southern Road now – a slightly different route, taken by the South Pole Traverse convoy taking supplies from McMurdo to Pole, oriented to go up a different glacier than the Beardmore. We followed this some of the way back, so I got a good appreciation of the road as a scratch on the cue-ball surface of the ice shelf. Returning parties tried to use their outbound tracks as much as possible to navigate home; sometimes the light was bad and sometimes they were covered by drift, but they'd often cross the tracks again once celestial navigation straightened them out, and that would put them back on course. A team of sledges with dogs and ponies is going to leave a fainter scratch than multi-ton tractors hauling vast bladders of fuel, but in a vista of windblown snow, a manmade disturbance can really stand out.

This tickles the same part of me that thrills at Oregon Trail wagon ruts and the South Downs Way.

Rather than following the road all the way back, as terrestrial creatures would do, we flew over White Island! This is the side which catches the wind from the south and east, so is not as white as the side you see from McMurdo.

And as we approached Williams Field, the light was just right to show off the sea ice/Barrier interface south of Cape Armitage.

The Sea Ice Incident happened in that bay! Right there! (I am still not over that.)

When we finally piled out of the plane, I thanked Steve enthusiastically for what had been by far the best flight of my entire life. 'Yeah, sorry about the turbulence back there,' he said.

'Oh that was nothing! I've had much worse coming in to Edmonton.' Which is true; I once made peace with death on a flight into Edmonton through a storm which, later that afternoon, spawned a tornado.

'Yeah, but's that's because you were flying into Edmonton.'

I can't argue with that: the Beardmore is definitely not Edmonton.

An article in the October 1911 edition of the South Polar Times – the magazine whose writing and publication kept the men happily occupied during the dark and crowded months of winter – posited Antarctica as a holiday destination in the distant future when global warming had rendered it balmy. In this antipodean Switzerland, tourists would travel comfortably by aeroplane over the geography which the men reading the magazine were, at that point, yet to walk across themselves. Wilson illustrated this article with a gauzy cloudscape and a wonderful spindly yellow biplane like the Wright brothers'. Cherry, writing on the other side of a war which saw the rapid development of aircraft into nimble and efficient vehicles, knew the future of Antarctic travel was in the air, and thought that sensible. I wonder if either of them could have imagined such a jolly picnic in the sky, going most of the route to the Pole and back in one day, in time for a nice hot dinner in the Galley.

August 1, 2020

Basler to the Beardmore 3: The Beardmore Glacier

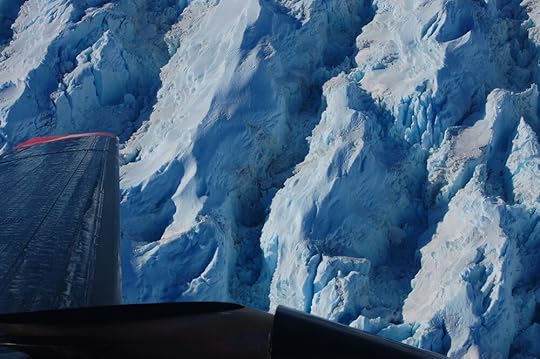

On leaving CTAM our practical business was completed for the day, so it was time at last to do some sightseeing. We were near the top of our glacier as it was, so we flew to the southern end of the mountain range to our east and then turned to round it, and suddenly, this was revealed:

First view over the upper Beardmore Glacier from behind a nunatak, or ‘island’ in ice (as opposed to a peak in a range of other peaks). There will be more on this nunatak later.

I knew the Beardmore was huge. No one has made any underestimations of it, in my reading. What I was not expecting, with all the analogies of glaciers to rivers, was that the Beardmore was practically a lake, if not a sea. We had just been on such a wide plain of ice that I thought that must have been it, but the real thing caught my breath in its vastness.

I can try to explain how big it was by reminding you these photos are taken from a plane quite high up, but a far better analogy can be made with a picture. The Beardmore Glacier is, on average, about the same width as the Salt Lake Valley (a little over 25km), which is similarly flanked by mountain ranges. Helpfully, the latter has has a modern American city sprawled across it, providing a context that most people will find more relatable than plains of ice. So here is a similar angle of that:

Photo ©Michael Hylland, Utah Geological Survey and used with permission. (original)

Not only were we turning the corner here, but the ice was as well, and the force of that showed on the surface. See, ice is a fluid! From this angle you can easily see that the glacier ice is in fact a light blue. This is the natural colour of ice; if the ice cubes in your summer drink were big enough, they would be blue, too.

The white stripes are snow settled in the troughs of the ripples formed by the ice flowing around the nunatak. The fingerprint-like cracks in the foreground are crevasses bridged by snow lids. These crevasses are easily a few hundred feet across.

When Shackleton first explored the Beardmore he reported it to be blue ice all the way up, with frequent crevasses, an account on which Scott based his plans. Some freak weather deposited thick soft snow on the bottom half of the glacier in December 1911, hiding the hard slippery surface under a blanket of miserable heavy stuff to pull a sledge through. By the time they got up here they were clear of it; I mention this now because my shots of the lower Beardmore are all into the sun so you can’t see that, in 2019, it was blue ice down there as well.

The clear blue ice of the upper Beardmore was not free of difficulty, however. Where the glacier meets the polar plateau – or, rather, where the plateau flows into the glacier – the ice breaks up as it pours over submerged mountains and buckles on itself. These are the Shackleton Ice Falls. It was a tricky enough business finding a path through them on the way up; each returning party had a worse time here on their journey back down. When the Polar Party failed to return in autumn 1912, those who had been on the Southern Journey all thought they must have died in an accident here.

It’s tempting to pick out a route from this high up, but imagine trying that from the ground!

The mountain we had come around was of no less interest. We did a few loops of the area, so I got to see that it had an unusual bench of loose rock that had been caught and pulled along by the glacier into quite an impressive moraine.

I thought I knew what this must be when I saw it, but, not having seen any photos, I didn’t want to jump to conclusions. After some investigation upon arriving home* I’m pretty sure this is in fact the Mt Buckley moraine where the Polar Party stopped for half a day’s ‘geologizing’ after surviving the harrowing icefalls. This was most likely a scientific gloss on giving Taff Evans a rest, as his condition was already starting to worry Scott, but it was here that they found a fossil Glossopteris plant which would ultimately contribute to proving the theory of continental drift. 35 pounds of geological samples, mostly from this moraine, were found with the Polar Party’s belongings when the search party found their last camp the next summer.

After another loop or two (I began to suspect that Steve was enjoying himself) we set off down the length of the glacier. This is some way down from Mt Buckley, where there is a slight pinch and the Beardmore turns a little more due north. That makes the nearer mountain The Cloudmaker, so named because the cold dry air coming off the plateau meets the damper air of the lower elevations at this turn, and produces clouds and fog. The far one with the distinctive fang shape is Mt Kyffin. It’s in the background of one of my favourite historic photos but I was astonished how big it was in context, in an already big place.

You can also see, here, the different textures of the glacier surface. On the western side is a wide smooth path, which is the way ascending parties came. Down the middle was a vast labyrinth of the most hideous pressure. We hadn’t flown any closer to the ice falls than the photo above, but this gives you some idea why the explorers thought them so harrowing. The photo above is deceptive, because it looks like it’s taken from standing-human height on the ground – I am in fact a thousand feet up, in a plane. Looking down on the pressure, like this:

. . . was like flying over Manhattan:

Manhattan photo sourced here; original photographer is Otman Lazra, for whom I have not found contact details. If you are, or know, Mr Lazra, please put us in touch!

As mentioned before, we had an incredibly clear and calm day at our disposal, so the Cloudmaker was off duty. Further down the glacier I got a stunning view of the smooth ‘highway’ on the west side, gleaming in the sun, with the mouth of the Beardmore ahead:

Around here we started to get into some turbulence, so instead of figuratively bouncing around the fuselage taking photos, I was instructed to strap in, in order not to do so literally. This prevented me from taking a bunch of glamour shots of Mt Kyffin, but that was providential, because it meant I saw this instead:

The two things I most wanted to get a sense of, on the Beardmore, were at the top and bottom: the Shackleton Ice Falls, as described above, and the feature known as The Gateway, a narrow pass at the bottom that allowed access onto the glacier without having to deal with the similarly hazardous glacier/ice shelf interface. There are few photos or sketches of this area from 1911, as explorers had their hands too full with heavy sledges sinking deep in the soft snow that wasn’t supposed to be there, but Bowers snapped this one of the dog teams turning back from the Gateway and I recognised it instantly.

The hazard they were supposed to be avoiding, by ascending via the Gateway, was a ‘chasm’ over which they never could have taken their sledges. What sort of chasm? Well, this is some idea:

Yeah, I wouldn’t want to try to cross that, either.

With that, we had left the Beardmore behind, and were on our way back across the Barrier to home. It should have been a quiet and relatively boring flight, but there were some more points of interest along the way, so I’m not letting you off the plane yet!

*Photographic records of this part of the world are scanty, one reason why I needed to go myself, and I hope my going has contributed positively to that record. Some helpful sources for ID-in what was historically known as Mt Buckley have been:

https://antarctica.recollect.co.nz/no...

https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/44290...

https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper...

https://d3i71xaburhd42.cloudfront.net...

If you have any further references, please do send them my way!

July 18, 2020

Basler to the Beardmore 2: Errands

On this flight to the heart of Antarctica, I was only a hanger-on. We had two errands to run before entertaining me and my historical interests, the most important of which was restocking a fuel depot at the base of the Transantarctic Mountains.

There are many busy science teams in Antarctica, and while some renewable energy sources are starting to be used, the fact is that everything runs on a reliable supply of fossil fuels, mostly petrol. The aircraft that keep people and their essentials moving around the continent have a network of fuel depots, both for relay stops and for emergencies. Contrary to some conspiracy theories, anyone can fly to and around Antarctica if they have the money and resources to get there, and many do. As the national science programmes have a very tight margin, and their fuel depots are expensive to maintain, they cannot afford jet-setters raiding their supplies, so the locations of these depots are kept secret. Therefore I am not going to tell you where our first stop was. The chances of a private pilot reading this blog are slim, but it may be possible to deduce from my photos where this particular cache is: if you are that outlier, I hereby ask you please to do the decent thing and leave the fuel alone – or if you absolutely must access it, then let the USAP know what you've taken and make good on it as soon as you can. Everyone in Antarctica looks out for each other, and that includes you. OK? OK.

So, we've taken off, and done our acrobatics to get the skis up, and are now facing a couple of hours' flight time before we reach our primary destination. There is, quite frankly, nothing between Williams Field and the Transantarctic Mountains, besides hundreds of miles of the Ross Ice Shelf. This was known as 'The Barrier' to the early explorers, because when James Clark Ross sailed down to explore in 1840 it was a great while wall that prevented his ships from going any further. In later years it wasn't so much a barrier as a highway – clear and flat, and not much off sea level, it provided a route deep into the high latitudes without the perils of the high windy Polar Plateau. Among people who frequently travel out there, it is sometimes referred to as 'the Flat White' – my impression is that this term came from the Kiwis, and the espresso drink of the same name is also antipodean in origin, so I wonder which came first. It is undeniably Flat, and White (though the refraction of sunlight through ice crystals makes it look anything from peachy to periwinkle, depending on the angle), but none of its various names communicate just how big it is.

I have flown over the Canadian tundra many times, and over the Greenland ice cap, but the view from 35,000 feet is like looking at satellite view in Google Maps compared to flying at cloud level, where the parallax with the horizon gives you a much keener sense of distance. The Barrier is BIG. In fact, 'big' is too small a word to communicate it. 'Massive', 'mammoth', and 'gargantuan' are more melodramatic than descriptive. Its vastness puts all of human consciousness, never mind vocabulary, in proper perspective. For my money, it outdoes the night sky as a visual approximation of infinity.

Getting a sense of its size, especially in a still photo, is difficult without an object for scale. For your education and my good fortune, we happened to fly over the RAID convoy as they made their way from the Minna Bluff site to where the Ross Ice Shelf meets the Antarctic continent. Rapid Access Ice Drilling has been supporting various scientific projects for a few years now, whether their interest is in the ice itself (its trapped air gives a record of Earth's atmosphere in millennia past) or what's underneath (marine environments far removed from the open sea; the bed of an accelerating glacier). Their units are about the size of a shipping container, and are pulled by enormous tractors, so if they are this dwarfed by the Flat White, imagine how much more puny a sledge party would be.

Before too much longer we were at the depot. Landing at an Antarctic field airstrip is even more complicated than taking off: we circled once, to do a visual check, then skimmed it with the skis to make sure no hidden crevasses had opened up since the last time someone landed here, then finally touched down for real on the third go-round. The plane crew rapidly got to work unloading the fuel drums; I offered to help but was assured I wasn't needed, so spent the time taking photographs and mucking around in the snow.

The first thing that struck me was how beautiful the mountains were in colour. The best photos I've seen of them have been black and white, so the rich variety in shades was remarkable. What you can't see in this small photo was how the lighter rock was banded with strata of blue-grey and orange-brown sandstone, giving it a luxurious marbled effect.

I've read a lot about how conditions on the Barrier are so much different than on the coast. This was far deeper into it than I was ever expecting to set foot, but I was surprised how tame it was. Now, it was an idyllically calm and sunny day – had it been any different we would not have been there – so the only time I realised that it was actually much colder than McMurdo was when a slight breeze wafted past my bare hand and broke the warm spell that the sunshine had cast.

What was different was the snow. Around McMurdo, the snowbanks which did build up had been repeatedly blown over with volcanic dust which warmed up in the sun and made the snow gritty, icy, and rotten – if you live in a snowy city, think of the texture of snowbanks alongside busy roads. Out here, there was nothing but snow, all the way down to where it became ice – powder blown off the mountains, maybe even off the Polar Plateau, deposited here to be compacted in the sun and polished by the wind. The crust made by these processes was smooth and, in many places, thick enough to support my weight, so I hardly left a footprint – a 'good pulling surface' as sledgers would have it – but without warning there would be a thin spot where my foot would break through and sink in the sugar-like snow below.

Tracks left by the Basler's landing gear. Without an object for scale, they might be sledge tracks, or crevasses, who could say?

Before long, the crew had finished their restock, and playtime was over. After our exciting takeoff manoeuvres, we started climbing the mountains to the second of our tasks for the day.

The Transantarctic Mountains, according to our pilot, are still something of a mystery. They are a very high mountain range, but unlike the Rockies for example, they show little or no sign of buckling or other geological forces – they seem to have been lifted whole, keeping their layers of sandstone and coal and fossil-rich deposits mostly flat, with occasional intrusions of igneous rock. The range acts as a sort of massively oversized dyke, holding back the miles-deep polar ice cap from spilling over West Antarctica, the Ross Ice Shelf, and the Ross Sea, as the mountains cross the continent.

Ice appears to be solid, but it actually behaves more like a stiff jelly or fondant icing – if it finds a change in altitude it will flow, very slowly, downhill. This is what a glacier is: snow gets deposited over many years without melting, turns to ice, and when its volume can no longer be held at elevation, starts to creep down the valley. The ice of the Polar Plateau finds gaps in the Transantarctic Mountains and pushes through them, forming glaciers which pour out onto the Ross Sea and, merging, form the Ross Ice Shelf. The Beardmore Glacier is one of the largest of these, but there are hundreds of smaller ones, and many tributary glaciers that feed these. In flying over the lower Transantarctic Mountains, there were plenty of opportunities to see ice dynamics at work:

Look, it flows!

Our destination was up near the head of a narrow glacier, where it broadened out into a snowy plain called the Bowden Névé – névé being a term for young snow which has not yet compacted into glacial ice but is in a position to do so. This was CTAM (pronounced see-tam), a geology camp established to be a hub for teams doing work in the Central TransAntarctic Mountains. The névé afforded an open, soft, flat place to land planes carrying supplies and people, who could then move on to less accessible places overland. At least, it did, until a wind event a few years ago scoured deep furrows in the landing strip.

As we flew over, doing the visual check, I was astonished the site could be spotted at all, as it was only a small clutch of bamboo poles in the vast expanse.

I did recall, eventually, that GPS is a thing. I may be spending too much time in the present, lately, but some parts of my brain are permanently stuck in 1910.

It was such a wide plain, and so magnificent a vista, that I thought it was the Beardmore at first.

Having proven that the landing strip was landable, the next task was to see what condition the building was in. What building, you ask? Why, the one completely covered in snow, under the markers. Once upon a time it was a couple of modules standing on the surface of the glacier, but Antarctica gradually swallowed them up, so now one has to dig down through the snow to reach the roof hatch, eight feet above the floor.

On the way from the Basler to the camp site, I was treated to one signature snow effect I had missed out on, at the depot. 'The Barrier Hush' is frequently mentioned in journals: it was described as a 'whoosh' or a 'hush-shh-shhhh' that sighed out from underneath the walker as he broke through the top crust into a pocket of air underneath, where the loose snow had settled after the top crust was formed. The pocket could sometimes extend quite a long way from where the crust was broken and the sound followed the exchange of air as far as it went. It would startle the ponies and excite the dogs, until they learned there was nothing to chase and catch.

I was walking some way behind the plane crew as they made for the camp with shovels, and suddenly heard what I thought was a small whirlwind – a sharp and intense, almost whistling sound that seemed to race across my path. This being the sort of place one would expect to see dust devils (or snow devils, I suppose they would be) I looked around to see where it was, but the air was as still up here as it had been down on the ice shelf. It was only after the second or third time it happened that I realised what it was – it was so completely not how I had imagined the Barrier Hush to sound. If you make a little whirlwind sound by whisper-whistling whshwshywshwhwwsh with your lips really quickly, that's what it sounded like. Having heard it, now, I can completely understand how the dogs would have thought there was a small creature scurrying around under the snow. It sounded much more animate than it had been described. I felt so lucky to be let into that secret.

The crew got the hatch open and the first of them climbed down into the pitch darkness to report everything OK. The rest followed, and invited me along, but I am not the most coordinated travelling artist, and couldn't see a way down for me that didn't end in a concussion. So I stayed above while they explored the submerged camp, and enjoyed the view. It was really spectacular – not just the stunning mountains but the thin, brittle blue of the sky and the hardness of the sunlight, as if the whole world were a taut drumskin.

And, best of all, from here the horizon was the Polar Plateau – another Flat White stretching to the South Pole and beyond.

July 4, 2020

Basler to the Beardmore 1: You See a Plane, You Take It

When planning my research trip with the Antarctic Artists & Writers Program, I had to make a wishlist of places to visit. One of the more important ones was the Beardmore Glacier, the route by which Scott and his men climbed from the Ross Ice Shelf (or, as they called it, the Barrier) to the Polar Plateau. It's one of the largest glaciers in the world, but is hardly visited anymore so is rarely photographed, and despite the blessing of Google Image Search, I had too poor a sense of it to draw a journey up or down it with any confidence.

Setting foot on the Beardmore turned out be prohibitively demanding, logistically, but there are regular LC-130 flights between McMurdo Station and the Pole which traverse the Beardmore en route. The plan we made was for me to get on one of those, and snap as much as I could from one of the small windows as we flew.

November 2019 turned out to be a terrible time for Pole flights – if the weather was OK at Pole, there was a problem with the planes, or vice versa. However, the weather delays worked in my favour, because they affected not only Pole flights, but one particular season-opening flight, which had been bumped so many times that it still hadn't gone when I turned up. That meant I could get a seat.

The big flights ffor the USAP’s operations in East Antarctica – cargo and passenger flights on/off continent, and to major stations like Pole and WAIS Divide – are handled by the New York Air National Guard, and their fleet of enormous military airplanes, namely a C-17 and small handful of LC-130 Hercules. There are lots of smaller trips from McMurdo to satellite stations, and these are serviced by Kenn Borek Air, a Canadian company which operates out of Calgary, Alberta. At the start of every season, they fly their fleet of Twin Otters and Baslers down the length of North and South America, then leapfrog depots down the Peninsula and thence to various hubs including McMurdo. From there they move people and stuff where they need to go, and also restock those fuel depots. There was one depot flight that remained to be done, and it happened to be to a cache near the base of the Beardmore, so they agreed to take me along.

I was not the only extra job tacked on to the flight. After depoting the fuel, we were to scout out a camp in the Transantarctic Mountains which had been in regular use until a some fierce winds a few years ago had scoured great furrows in the landing strip. Was it landable again? What state was the camp in? We would find out. They also wanted to scope out a historic site that left no physical trace, to get updated intel on its condition. Then we would fly north again via the Beardmore and the coordinates for One Ton Depot.

As soon as the Basler had finished her more pressing engagements, we were put on alert for the depot run. Everything in Antarctica is weather-dependent, and that can change on a dime, so one is always on standby. Because they needed to make the most of the Basler's time, they would put two missions on for any given day, then the one with the best prospects would be activated. For five days I was ready to go – breakfasted, fully suited up, lunch packed, ECW bag to hand – at 7 a.m., in case my flight was the one that was going. Flight status would be announced on the screens at the entrance to the Galley.

For four mornings I joined the poor Thwaites Glacier team anxiously hanging on the screens – they were trying to get out to WAIS Divide (the high point of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, from which they would catch a flight to the Thwaites camp) where the weather had been abominable for a month. One of those mornings my flight was activated and I got all the way out to the airfield only for it to be called off at the last minute because of a change in forecast for the depot site. But finally, the fifth morning, it was all systems go!

There are two airfields that serve McMurdo: Phoenix, which is designed to take the massive C-17s on a packed snow runway where they can land with wheels, and Williams Field, of groomed snow, for ski'd aircraft. The extra special thing about Williams Field is that it's more or less where Scott's 'Safety Camp' was located – so named because it was far enough onto the ice shelf not to break up and float out to sea – so the view to Ross Island from there would have been very familiar to our explorers. On the day of my false start, while waiting to find out that the plane wasn't going after all, I got to take some good pictures of the view from there. It was also a good day to get a sense of the 'bad light' that obliterated contrast on the snow and made navigation difficult:

The Sea Ice Incident took place between us and the conical hill to the left! Wild!

Anyway, Try no. 5 was on a much nicer day. Here is the magnificent bird with her spanking new paint job:

The cargo was me and those five oil drums.

It wasn’t such a bad seat, though – I got to watch the flight deck all day!