Maria Yrsa Rönneus's Blog, page 12

December 20, 2020

Life in Times of Cholera

Anno Domini 2020 has been a bad year for everyone. Covid-19 has ensured its place in history alongside years like 1347 or 1816; and the pandemic has affected all of us, directly or indirectly.

Having spent nigh on ten months and counting in self-isolation, my personal grievances are mere trifles compared to the horrendous experiences of scores of others worldwide. Yet 2020 broke me. As if the weight of my life’s collected sorrows had fallen on top of me. For months now, I have not been able to write or paint. In truth, I have just barely functioned. I lost myself in the vortex of a world that seemed to spiral out of control around me, adding tears of a long time ago to the persisting precipitation of current woes.

Stress is a peculiar thing.

–‘Oh please, do you think you are the only one who has lived through a pandemic? I was at Calcutta when the cholera pandemic first broke out in 1817, remember?’ There is a tinge of disdain to the green sideeye Lady Marigold gives me.

–‘Yes, I remember.’ I say, feeling ashamed.

–‘You ought to, you placed me there after all. With two infants at that!’

–‘I know. I’m sorry.’

I wonder if my talking to fictional characters again means that I am getting better… or worse.

The plan was to have novels no 3 and 4 in my Regency Tales series published by now, but alas, it was not to be. While only last edits remain on no 4, ‘Orbits of Attraction’, I am still only about two thirds through no 3, ‘Odyssey of Attachment’. My apologies, Dear Readers, but you shall simply have to wait a little longer.

What posterity has come to refer to as the first cholera pandemic, was to people two centuries ago, every bit as frighteningly unpredictable and mysteriously fatal as covid-19 has been to ourselves. It is believed to have started near Kolkata, and from there spread by people’s travels. Cholera was not a novelty before 1817, in fact, local outbreaks were fairly common and at the onset of the outbreak, few saw cause for worry. This time, however, the disease behaved somewhat differently.

British troops were no small contributing factor in its spread to nearly every part of the world. Alongside the disease xenophobia ran rampant; then, as now, Asians were blamed, Hindu and Muslim pilgrims in particular. It is difficult to say exactly where and when the first cholera pandemic ended and the second began, and historians are in disagreement. The disease seems to have tapered off for a few years to gain new momentum and spread via Russia into Western Europe in 1832. That same year The Medico-chirurgical Review and Journal of Practical Medicine republished the Bombay Medical Board’s report on epidemic cholera (1819), harsly criticizing the Bengal Presidency’s handling of information, treatment, and prevention of the disease.

“The danger seemed too remote to excite attention or to warrant alarm, and although a few physicians, attracted by curiosity, or by partial motives, devoted a slight degree of consideration to the subject, it was never fully investigated even by them. Many bad consequences have ensued from this general professional ignorance, but the effects resulting from the state of imperfect information and semi-knowledge, disseminated by the dabblers in the Indian reports, have been infinitely worse. Statements of false facts have been boldly made, and pertinaciously persisted in; a colouring has been given to other facts and opinions which possessed a real existence; general impressions have gone abroad founded rather on such bases as legendary tales, than sober historic records; and the result has been error, uncertainty, and confusion.”

Neither fake news, nor dilettantes expressing errenous opinions in media are new phenomena.

The Bengal Presidency’s own report came in 1820. In it, government surgeon James Jameson went to greath lengths to prove that the outbreak may not have started at Jessore at all, as claimed by the Bombay report. The implication being, of course, that if a place of origin could not be assertained, then it may not have started with in the Bengal presidency at all, and then its government could not be held responsible.

In an all too familiar shit-flinging and blame-shifting contest, the governments of the time sought to cover up their own failure to react and act promptly. It was argued that cholera had been around before, this time around it was only exceptional because of its spread, and that in any case lots and lots of people died in India before the epidemic from other causes.

That has a strangely familiar ring to it too.

The simple truth is, of course, that epidemics or pandemics, whether caused by virus or bacteria, are naturally occurring phenomena that can affect all living creatures. Today the cause of cholera is known to be a bacteria found in undercooked food; poor sanitation, dirty drinking water, and poverty in general are main causing factors. Modern treatment consists of antibiotics and rehydration therapies. The intravenous saline drip was pioneered in 1832 by Dr Thomas Latta of Leith, who, like so many medical personel on the front lines, perished in the disease he fought.

–‘So are you going to write me out of this mess or not?’ Her snarl annoys me. She wanted an adventure, and I gave her one. Adventures are rarely safe.

–‘You are not the boss of me, Marigold!’ I snarl back. She raises her eyebrow sarcastically, and we both know without a shred of doubt that she absolutely is.

July 4, 2020

A Writer’s Waterloo

Some chapters are harder to write than others. In my upcoming novel ‘Odyssey of Attachment’ the protagonist finds herself in Brussels at the time of the battle of Waterloo.

And Dear Reader, I must own that I have toiled with this section for over three weeks now. First, I went through the usual phases: defiance, acceptance, surrender. The truth is that I did not want to write it, and I wanted to research it even less. I find it boring and grisly at once, yet it had to be done.

The Battle of Waterloo is one of the most renowned, reiterated, and analysed events in the history of the world. And perhaps rightly so. It is still continually debated, reimagined, and reenacted. The Waterloo campaign was rather a series of three battles, strung together in complex chains of action – a Pandora’s box of battles within the battles – which all have been mapped out in minute detail. Such thorough descriptions of those horrid days are not the object of my novel, yet they cannot be ignored either. After having been at war for nigh on a quarter of a century, hardly a single person in Britain was unaffected by it. So writing about Waterloo had to be done.

Newspapers, poems, and novels in the following decades praised the soldiers in terms of gallantry and glory. In reality, it was insanity and gore.

Edward Orme’s depiction was published some years after the battle and presents a censored and wildly inaccurate version of the battlefield.

Edward Orme’s depiction was published some years after the battle and presents a censored and wildly inaccurate version of the battlefield.

Some husbands, sons, or brothers never returned, others did, but maimed and traumatized. Unless you were wealthy, like the Marquess of Anglesey, life as a disabled person was often a sentence to a slow and painful death. If an amputee did not perish from infection and fever, he was condemned to unemployment, begging and starving in the streets.

Delving into the graphic descriptions of the gruesome violence of the battle and the unimaginable suffering resulted in exhausting weeks of agonizing over each blow and crying for each fallen man and horse. I can’t keep a distance emotionally if I want my characters to come out believable; for better and worse, I must feel what they do.

Then nearing four thousand words, I made a terrible discovery. Despite all that research, I had overlooked one crucial piece of information, one that would alter my protagonist’s perspective entirely.

My whole self protested loudly, haggling to try to get away with it as is. But given the well-known circumstances, there is nothing for it but to begin again. Times like this are when I wish I was writing fantasy and could just make things up.

Something akin to a cavalry squadron, historical fiction is easy to rouse and hard to rein in. Once it’s unleashed you never know for certain where it’s going to end up. Much like the Royal Scots Greys’ infamous charge on the French infantry. And much like Wellington, I grumble when the facts do not fit my masterplan.

But defeat is not an option! So when I have stopped kicking myself, I shall be spending the weekend re-reading Siborne’s ‘History of the War in France and Belgium’ (1848). And, hopefully, at the end of it I shall be able to round up my rogue facts and make a last dash for closure of the chapter.

With that, Dear Reader, I wish you a happy Saturday!

June 19, 2020

The First First World War

Events more distant to us than a few generations ago tend to fade in our collective consciousness, and their impact on our own time become overshadowed by more recent events.

Had the Grande Armée defeated the British and the Prussians that gruesome day 205 years ago, the history of Europe, and by extension its colonies’, would have been vastly altered. All succeeding events in Europe would have played out differently. Not necessarily better, but differently.

The amount written about the 18th of June 1815 can be measured by the shelf metre. Not as much has been said about the day after the horrors ended. The Belgian fields were scarlet, blue, and green with scattered regimentals. What passed through the soldier’s mind when he woke up on the battlefield, realizing that he was still alive? Did the bees buzz between flowers? Or did rain whip his face? Was he in agonizing pain?

Victors get to write history as well as choose the language it is written in and Napoleon’s defeat was one deciding factor why English rose to be the world’s lingua franca. (Ironically.)

Determining the narrative is the prerogative of the victors, but more specifically of the wealthy and prominent victors. More rarely do we get to hear the voices of regular troops. What were their opinions of the wars, their government, and their enemy? Did they believe the propaganda? Or did they just want to go home?

While the information available about British soldiers is sparse, French accounts and perspectives are still largely unavailable outside the francophone sphere despite efforts of translation in more recent years.

Sadly, too often simplistically portrayed in films and novels as fanatic and bloodthirsty Napoleon supporters, the truth is that French soldiers were very much like the British. They were the conscripted sons of peasants, labourers, and artisans who had no choice but to fight.

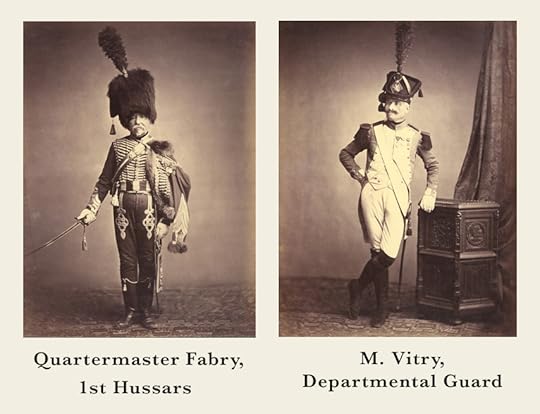

Brown University Library has made their collection of 1850’s photographs of surviving French Waterloo veterans available online.

When the romance writer in me can’t help but gush over how dashing and handsome they are, my amateur historian half whacks her over the head with a scabbard. It was anything but glorious and romantic. War is always gory and inflicting unspeakable horrors on soldiers and civilians alike.

Let us never forget that.

June 18, 2020

A Mind To Midsummer

None of my novels (so far) take place during Midsummer, which is a great shame because it is my favourite holiday. Midsummer is said to be either the beginning of summer or the middle of it, depending on who you ask; for myself however, it sooner marks an end. The end, or perhaps the grand finale, of the prettiest time of year. The greenery is still lush, columbines nod sweetly everywhere they weren’t sown, and the first strawberries can be harvested. When the gilliflowers perfume the cool, bright nights there is magic in the air. It is not difficult to understand why the summer solstice has been a time for sacred rites through the millennia.

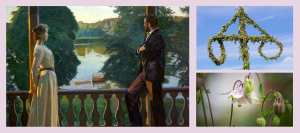

‘Nordic Summer Evening’, Richard Berg, 1899; a Swedish Midsummer pole; pink columbine in mist

‘Nordic Summer Evening’, Richard Berg, 1899; a Swedish Midsummer pole; pink columbine in mist

Precisely what those ceremonies were has been, and continues to be, a matter of debate and a good portion of imaginative conjecture.

Sifted through the reformation, the ancient traditions were significantly diluted. With the age of enlightenment old superstitions fell out of favour along with anything that was deemed irrational. By the 18th century, the feasts and the dances had become exclusive to rural farming communities. Aristocrats and gentry might have watched in patronizing amusement, but did not partake as a rule.

Moreover, upper and middle class recorders often did not bother taking down or observing in great detail the traditions and beliefs of the “rustics” above what could be curious or charming to their audience. Traditions could vary a great deal between different parts of a country, unfortunately, the available knowledge is fragmentary at best.

In Scandinavia Midsummer, as well as other old traditions, were reignited and reimagined with the romantic nationalism at the latter half of the 19th century. Geopolitical events in Europe led to the want of national identity and pride. Old ballads, texts, and traditions were dusted off and (quite arbitrarily) held up as proof of our past glories. Throughout Europe, artists, authors, composers, and “historians” busied themselves with forging suitably splendid histories for their homelands. Most of the “histories” were complete nonsense of course; my father’s old schoolbooks e.g. unabashedly claimed that Swedes are the direct descendants of Odin.

From the 1970’s onward new age and pagan groups have done their bit to add to and subtract from what little was known, blurring the boundary between fact and fiction further.

While it is the natural order of things that traditions, culture, and language should evolve and change over time, it makes finding out exactly how Midsummer was celebrated in the past fraught with pitfalls.

What we can take for probable is that Midsummer in Scandinavia was a time of fertility rites (it was finally warm enough to go outside and have some privacy) and excessive drinking. So far little is changed.

In Sweden, the ancient custom of decorating churches and halls with greenery meant making wreaths and garlands of birch and flowers and even bringing in whole young trees. In more modern times, some people put twigs of birch into their car’s grille. And of course, the main event: the erection of the Midsummer Pole. (In English speaking countries usually referred to as a May Pole.) Around it people would dance either as couples or as groups circling the pole. Many of the dances were at the same time games in which young people were ultimately coupled off. All of this is still common practice, although the dancing has sadly withered to being either exercise for toddlers and small children, or exhibition by usually aging professional dancers.

It was a time for magical creatures to come out to help or hinder, and conditions for making predictions were particularly favourable. Perhaps influenced by all creatures seeking their mate and nesting in spring, perhaps owing to ancient fertility rites, June and Midsummer was the time for love. Perhaps it also had more practical reasons; after a busy spring of toil and tillage, farmers finally had time to throw a wedding party!

On Midsummer’s Night young maidens could go picking seven (in some places nine) different kinds of flowers and sleep with them under their pillow. If they had been completely silent and the magical powers were benevolent their future husbands would appear in their dreams. I remember doing this as a young girl, almost every year, mainly for sport but well…one never knows, right? But alas, the only time I ever dreamt of a person was after watching a Hitchcock rerun with my mom and then I dreamt of old Alfred himself. Not the most exciting of prospects for a twelve-year-old.

More useful to older and already wedded persons was collecting medicinal plants, which were especially potent if picked on Midsummer’s Eve. In fact the magic of that night was such that even the dew gathered could cure and prevent illness.

In Midsummer time streaks of nocturnal mist often hover over fields and meadows and the imagination easily runs wild with the fairies in the enchanting golden twilight. In Scandinavian lore those mists are in fact elves dancing. Whether that is true or not, it is not hard to see where Shakespeare got his inspiration from.

This year I’ll be picking flowers for my husband and walk barefoot through the dewy grass. I hope that you, Dear Reader, will celebrate Midsummer with extra caution; keep the distance, wear a mask, wash your hands. And save the dancing ’til next year. Oh, and whatever you do, do not piss off the fairies!

Happy Midsummer!