Joy Neal Kidney's Blog, page 68

June 14, 2021

Flag Day

The American flag was precious to my grandmother, Leora Wilson. One of my favorite pictures of her is under a flag at my parents’ farm near Dexter.

Back in 1890 when Leora was born, Idaho and Wyoming had just been added to the Union, making 44 stars in the flag. Utah became a State when she was 5, the year her father went bankrupt in Nebraska’s drought, adding another 45 star to the flag.

Leora was nearly 17, living in Audubon County, Iowa, riding a horse to town to take piano lessons, and helping her dad in his fields of popcorn, when Oklahoma was admitted to the Union. 46 stars.

The 48-star flag came about when New Mexico and Arizona became states right before the Titanic sank. Leora was 21 then, living at Wichita, Iowa, not yet married.

It was that flag, with 48 stars, for the next 33 years. . . through Leora’s marriage, the Great War, the births of her 10 children, the loss of three as infants, WW II. . . and the loss of three sons during that war.

Making her a Gold Star Mother.

Flag Day was also important to her. She’d display the American flag at her little house in Guthrie Center.

Her family had sacrificed so much for that flag.

In September 1945, when Japan officially surrendered after WWII, Leora’s son Danny was still Missing in Action in Austria, although the war in Europe had ended months before. In fact two sons were still Missing in Action–Dale and Danny.

Their youngest brother, Junior, was killed in training at the end of the war. An American flag had been presented to Clabe and Leora by Junior’s Army Air Force friend, Ralph Woods, at the funeral.

War was over. The Wilsons’ two surviving sons had served in the Navy. Delbert and his family moved home to be with his folks. Donald stayed in the Navy. Daughters Darlene and Doris, both married, also lived in Iowa. Four small grandchildren kept Clabe and Leora entertained, at least part of the time.

Harry Wold, a pilot friend of Danny’s, who’d been his “stone hut mate” in Italy while in combat, wrote that he still hoped that Danny would be found–maybe in a hospital, but he was skeptical.

On September 26, 1945, a carton of Dan Wilson’s things arrived at the Wilson acreage south of Perry–sent from the Army Effects Bureau of the Kansas City Quartermaster Depot.

Clabe signed for the carton. I suppose they opened it, but did they sort through their son’s eighteen pairs of socks, five cotton undershirts, three khaki trousers, and other clothing? If they had, they would have found Danny’s wrist watch, souvenirs of his R and R to Rome over Christmas, a fountain pen, other items including a small New Testament.

Yes, the war was over, but life just kept on and on. . . .

According to Leora’s notes, she churned butter every week. Two cows had calves. Clabe helped a neighbor with field work.

At some point, they would have thumbed through the Danny’s small New Testament.

They would have found the page with the American flag pictured in color.

Under that flag is an arrow, drawn in ink, and the words in his bold printing, “I give everything for the country it stands for. D. S. Wilson.”

Daniel Sheridan Wilson. . . . Danny.

If this brings tears to my eyes, these many decades later, how did my grandparents deal with it then?

No wonder the American flag was precious to my grandmother.

In the picture of Grandma under the flag at my parents’ place, she’s wearing a watch with a small silver bell fastened to it.

The Capri bell arrived in the same box as Danny’s small Bible. . . . with his personal pledge to the American flag.

Featured on the front page of the Opinion section in the June 14, 2020 issue of The Des Moines Sunday Register.

June 12, 2021

The Needle in Her Hand

An 8-minute Leora story from the Great Depression, which also includes a little history from a Bonnie and Clyde shootout in Dexfield Park.

First aired by Our American Stories on June 9, 2021. Produced by Matthew Montgomery.

Leora’s Dexter Stories: The Scarcity Years of the Great Depression is the second book in the Leora’s Stories series.

June 11, 2021

John Neal, Muralist at the Iowa Gold Star Museum, Camp Dodge, Iowa

I’d visited the old Iowa Gold Star Museum at Camp Dodge, Johnston, Iowa, several times, usually with Mom, so this new one was a compelling surprise. Curator Michael Vogt wrote an excellent introduction to the museum in the Iowa History Journal.

Artist John Neal (no relation) has completed several murals for this one, each one of which enhances the display it anchors.

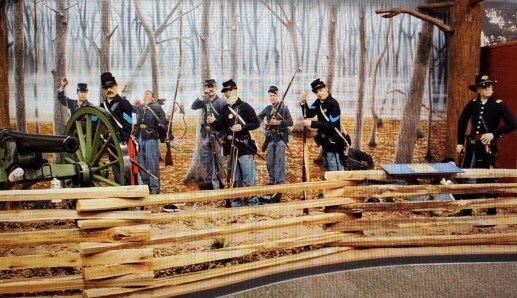

Civil War

John’s Civil War mural is the backdrop for the Civil War display at the Gold Star Museum.

Michael Vogt was recently interviewed about Iowa in the Civil War.

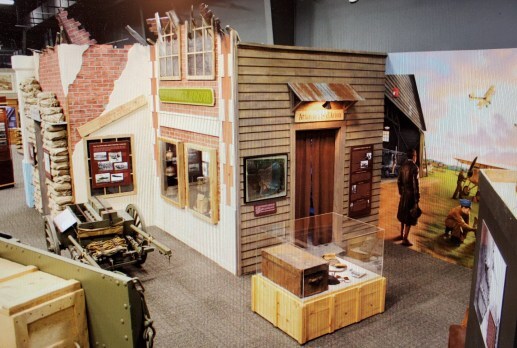

World War I

The damaged storefront houses a display of a WWI trench at night.

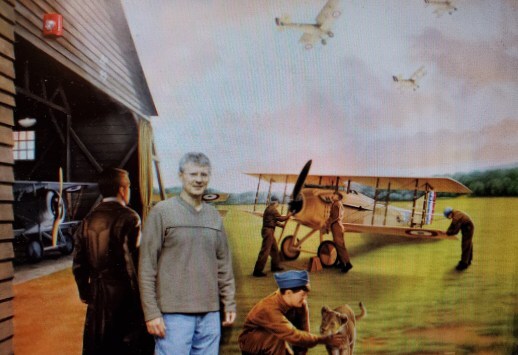

Artist John Neal next to his mural of a morning sky over a French airfield. They did have a couple of lion cubs as mascots.

World War II

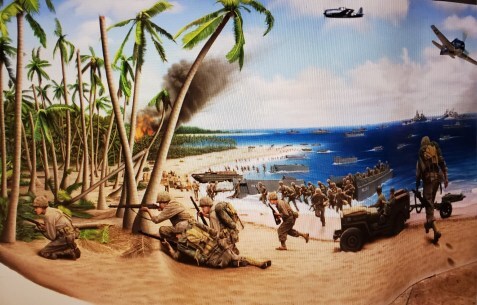

The first photo shows the mural for the Pacific Theater exhibit, of landing on a Pacific Island. The second one is the completed exhibit.

The day my husband and I visited, John and his son Cameron (who is also an artist and musician) were working on the WWII mural. Nearby were several books they used for research.

Korean War

The nose of this F-86, like the one piloted by Iowan Capt. Hal Fischer, is a fabrication. John completed the rest of the fighter on the curved wall of the exhibit. Marsden matting was used for runways and taxiways.

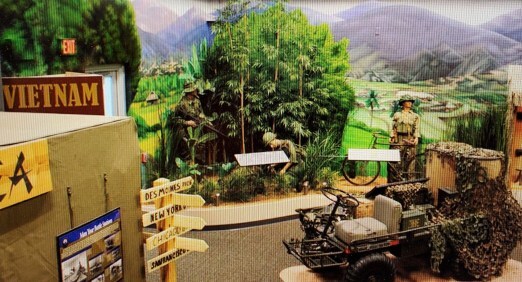

Vietnam War

The completed Vietnam War exhibit with a mural by John Neal, who did a lot of research as he worked on each display.

Cold War

This amazing exhibit is a replica of a nuclear submarine conning tower, with one of John’s murals wrapped around inside.

Here’s an award-winning virtual tour of the museum.

John Neal’s website shows more of his handsome and engaging artwork.

The Gold Star Museum has a YouTube Channel. The clips are not long, well-edited, treasures for all of us. If you enjoy them, please Like, Share and Subscribe.

Autographed copies of Leora’s Letters: The Story of Love and Loss for an Iowa Family During World War II have been donated so the Gold Star Museum may benefit from the proceeds. Find it in their gift shop.

June 10, 2021

Thursday Morning (poem)

Thursday Morning

I called my motherto see how many rugsshe’d shaken today.–When you’re in your eightiesshaking rugs is a realaccomplishment.–None today, she said,but she’d planted nine rows of gardenand mowed the barnyard,all before nine o’clockthat morning.–And she was preparingto clean up and iron a littlebefore raising the dustwith her red Buick,heading toward town forher weekly hairdo.–(2004)June 9, 2021

Lamb’s Ears (poem)

Asima wearing a dimije, Bosnia, 2001Lamb’s EarsThe women in blousy dimijes,scarves hiding long hair,don’t speak English.I, with short hair, wearing jeans,don’t speak Bosnian.Nearby grows a fuzzy, grey-green plant.As I stroke its softness,I bleat, “Baa-a-a.”With my hand, waggle an ear.They look at each other for a moment,then laugh. No dictionary needed.Published 2005, Home Forum.

Asima wearing a dimije, Bosnia, 2001Lamb’s EarsThe women in blousy dimijes,scarves hiding long hair,don’t speak English.I, with short hair, wearing jeans,don’t speak Bosnian.Nearby grows a fuzzy, grey-green plant.As I stroke its softness,I bleat, “Baa-a-a.”With my hand, waggle an ear.They look at each other for a moment,then laugh. No dictionary needed.Published 2005, Home Forum.

June 7, 2021

A Couple of Memoirs I’ve Enjoyed

by Robert Frohlich

“Why am I still alive?” That question was in the back of his mind when in 1965, Robert Frohlich was headed out towards Arizona to look for a job after serving in the army for three years. Escaping a splintered family and a troubled past, his car broke down in Wisconsin. Through a series of events that involved finding life-long friends, stable work, and the love of his life, he never left, finally finding a place to stay after wandering for most of his life.

However, that was not the first time God caused Robert’s life to change direction, nor will it be the last. By learning to trust in the Lord and let things come as they may, Robert has led a fulfilling life serving God, his family, and his community. Aimless Life, Awesome God is the story of Robert Frohlich, but it is also the story of anyone willing to let God redirect their lives according to His awesome plan. Learn more about the author at: RobertFrohlichAuthor.com

My Thoughts: What an amazing life, an amazing story of God’s hand on one life, in spite of a broken childhood and even poor choices. I love stories that show God’s surprising nudges in a life through the decades, and the influence of that life on those around him.

Bob Frohlich’s compelling stories have been shared by Our American Stories”

3, 2, 1, You’re It! (11 minutes)

Learning to Drive (19 minutes)

—–

Adventures Before We Were Twelve

by Gary Hawhee

It was exhilarating and sometimes painful to remember some of the things that happened to me and my family that I share in this book, Adventures Before We Were Twelve. There was the blizzard of 1936 that nearly took my baby brother Bill, who almost succumbed that year to pneumonia, and the time Dad almost scalped himself with a double bitted axe when he slipped on the ice while chopping wood. I’ll never forget the day my little brother Gale and I took our first train ride, all on our own, when he was just four and I was six years old. It was a sad day when our favorite horse “Molly” lost her eyesight. About that time equine encephalitis swept through the horse population in Southwest Iowa. I was seven years old and expected to help save one of our horses. Times were simpler back then, but it also took hard work to sustain the family. There were all kinds of adventures to be found on and around the farm in the 1930’s and 40’s. I hope you enjoy reliving some of my more memorable Adventures Before We Were Twelve. – Gary Hawhee, Author

My Thoughts: From stories about filling bedding ticks with cornshucks to the blizzard of 1936, from his little brother’s serious pneumonia to taking care of baby animals by the kitchen range, and the fear of bullsnakes to helping doctor horses with sleeping sickness–all before the age of twelve. There are lots and lots of horse stories by this veteran of the Korean War. Very enjoyable.

June 4, 2021

Visiting Bosnia–20 Years Ago

Twenty years ago, we’d been teaching ESL (English as a Second Language) at our church. The regular ESL classes were overflowing, especially with Bosnian refugees, so we were recruited to help out. Of course, you end up with new friendships.

I’d even gone to the birth of Adis, the small boy in the photos. I’d gone to prenatal classes with his mother Zlatka, but also knew what English she could understand. I could also restate the medical jargon for her at the hospital. No one asked if I’d ever been to a baby’s birth or not. I admit to having shaky legs and needing to sit a little afterwards.

When Adis was two years old, his family returned to Bosnia to see their parents. His father Samir suggested that I go along with them, that I’d certainly have a better idea of their backgrounds. So I did.

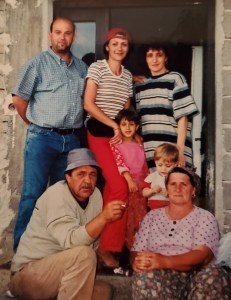

Samir’s parents had a new home because their other had been destroyed in the war.

It’s built of cement blocks and the upper floors weren’t yet finished. Samir’s three brothers and one sister also live in Iowa. The youngest sister is standing between Samir and Zlatka in the doorway, with Adis’s older sister Dzenaela (who was two years old when she arrived in Iowa) and Adis. Samir’s parents are in front. Since then, they’ve also moved to Iowa.

Adis and Dzenaela (pronounced Janella) wanted to help their nana haul hay to the cattle.

Most of Zlatka’s family still lives in Bosnia. Her parents are the man with the vest and the woman in white. Zlatka lost her two older brothers in the war. Since this photo was taken (2001), she’s also lost her father, another brother, and a niece.

Most of Zlatka’s family still lives in Bosnia. Her parents are the man with the vest and the woman in white. Zlatka lost her two older brothers in the war. Since this photo was taken (2001), she’s also lost her father, another brother, and a niece.

Six-year-old cousins Dzenela and Rifet are in front. Rifet would lean on my knee and try to carry on a conversation. My diary from 20 years ago today: “He told me to hold out my hand & close my eyes (Zlatka ranslated) & he gave me an apple. I later tried to put it on the tray & he said no, it’s only for you.” Wonder if he remembers. Will ask this morning.

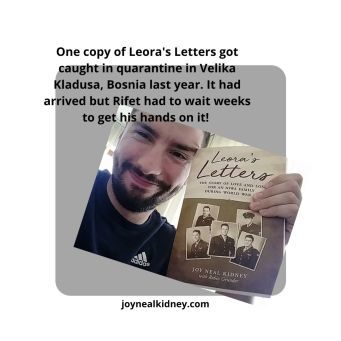

In the last couple of years, I’ve reconnected with Rifet via Facebook! He’s got terrific English and it’s been a delight to converse about several things via Instant Message. He was so interested in Leora’s Letters so I sent a copy, which got caught in the pandemic and wasn’t delivered to him for several weeks.

In the last couple of years, I’ve reconnected with Rifet via Facebook! He’s got terrific English and it’s been a delight to converse about several things via Instant Message. He was so interested in Leora’s Letters so I sent a copy, which got caught in the pandemic and wasn’t delivered to him for several weeks.

We raked hay one day. Zlatka’s mother with the beautiful backdrop of the home this family left because of no jobs.

We raked hay one day. Zlatka’s mother with the beautiful backdrop of the home this family left because of no jobs.Dzenaela completed culinary school and just got married this year. Adis finished community college and is a member of the Air National Guard. They have a younger brother (Denis) who is also a high school graduate and is working full time.

June 2, 2021

The Wilson Kids’ Birthdays – 1927

The Wilson kids’ birthdays fell between May 13 and September 14. Many times their Grandmother Laura Goff baked birthday cakes for them.

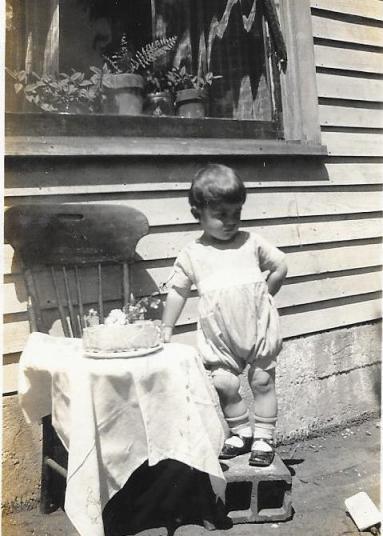

Both twins Dale and Darlene got his/her own cake – 6th birthday – May 13,1927 Creamery Road, Penn Township, south of Dexter, Iowa

Both twins Dale and Darlene got his/her own cake – 6th birthday – May 13,1927 Creamery Road, Penn Township, south of Dexter, Iowa Danny turned 4 on May 21, 1927. This was around the time of his mastoidectomy.

Danny turned 4 on May 21, 1927. This was around the time of his mastoidectomy. I believe this was taken on Delbert’s 12th birthday, June 3, 1927 Back: Donald, Doris, Darlene tucked in, Delbert. Front: Dale, Danny, Junior

I believe this was taken on Delbert’s 12th birthday, June 3, 1927 Back: Donald, Doris, Darlene tucked in, Delbert. Front: Dale, Danny, Junior Junior’s second birthday, July 6, 1927

Junior’s second birthday, July 6, 1927 Doris on her 9th birthday, August 30, 1927. “The quilt is a present from Grandmother Laura [Jordan] Goff. Most of blocks pieced by her great grandmother Emilia [Moore] Jordan. Danny and Junior watching lighted candles.”

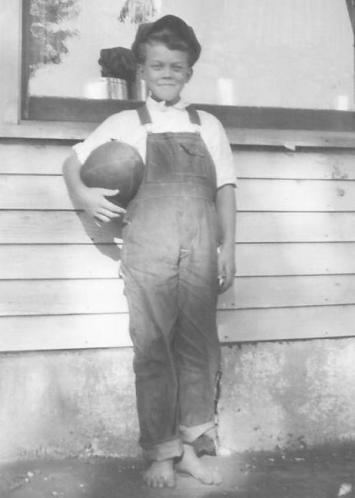

Doris on her 9th birthday, August 30, 1927. “The quilt is a present from Grandmother Laura [Jordan] Goff. Most of blocks pieced by her great grandmother Emilia [Moore] Jordan. Danny and Junior watching lighted candles.” I didn’t find a birthday photo of Donald, but here he is about that time. On September 14, 1927, he would have been 11 years old.

I didn’t find a birthday photo of Donald, but here he is about that time. On September 14, 1927, he would have been 11 years old.

June 1, 2021

Grandma Leora

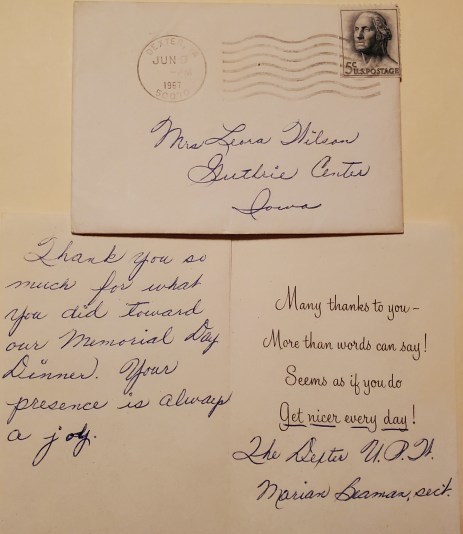

This sweet note gives me goosebumps.

Leora Wilson was my mother’s mother. Marian Beaman was my father’s youngest sister.

In 1967, the Dexter (Iowa) United Presbyterian Women offered a escalloped chicken dinner for Memorial Day, which had always been on May 30. Dozens of people ate there, before or after they’d taken flowers to remember loved ones at the cemetery.

Grandma Leora lived in Guthrie Center. This little thank you means that she was staying with my folks on the farm after having taken flowers to Guthrie Center and Perry cemeteries with her own daughters, most likely the day before.

After leaving flowers for her own parents, a sister, a sister-in-law, and three infants at Guthrie Center, then her husband and the three sons who were lost during WWII, she’d stay a few days with a daughter, either Doris (my mother) or Darlene.

Mom would have been in on this Memorial Day dinner, having been the treasurer for the women’s group for years. She’d also make a big pan of scalloped chicken and a salad or pie for the popular dinner. I was married and living in Idaho at the time, but when we were younger, my sister and I were among the girls who poured water and coffee and removed plates from the tables.

This little note means that Grandma Leora, who couldn’t sit still if there was any work being done within earshot, had helped out in the kitchen. She most likely washed or wiped dishes.

And Aunt Marian was right, Grandma’s presence was always a joy.

—–

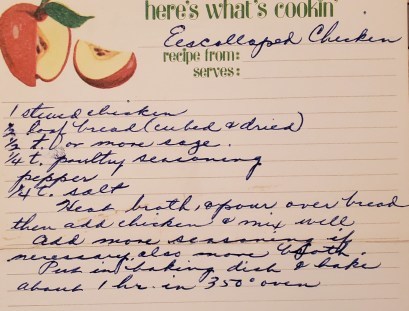

This is my mother’s recipe for escalloped chicken, which the UPW probably used for their dinners. It doesn’t say how much chicken broth to use, but I’m guessing a quart.

This is my mother’s recipe for escalloped chicken, which the UPW probably used for their dinners. It doesn’t say how much chicken broth to use, but I’m guessing a quart.

May 31, 2021

Memorial Day in Our Cemeteries Around the World

Memorial Day is the only day set aside each year to honor and remember America’s war casualties. Some of the most compelling rites are held in our cemeteries overseas, where locals will flock to commemorate the young Americans who helped liberate their homelands.

Those on the other side of the International Date Line will be the first to hold Memorial Day ceremonies. I think of Dale Wilson, whose name is chiseled on the Wall of Remembrance at the Manila American Cemetery, along with the five others who were with him, when their B-25 crashed on a mission. They have never been found.

Dale was the first of my grandparents’ three sons who were lost during World War II.

I think of the observances held hours later in eastern France, where another of Clabe and Leora Wilson’s sons is buried–in Lorraine American Cemetery, in Plot D, Row 5, Grave 7.

His is only one of more than 10,000 graves of Americans who lost their lives in the European Theater of War.

Four years ago, I logged onto my computer to find a photo of Danny Wilson’s cross, along with his photo and flowers. Mathieu Carre, a Frenchman and World War II reenactor with a real heart for these young Americans, had posted it on Facebook. He was as glad to contact the family of one of the boys buried far from home as I was heartened by his kind gesture. That December, Ivan Steenkiste from Belgium joined Mathieu for a photo at Dan Wilson’s grave. What a blessing to find it early one morning. Mr. Steenkiste is active in making sure the memories of the Battle of the Bulge are kept alive on Chaumont Ardennes Belgium Facebook page. Lorraine Cemetery is filled with American casualties of that terrible time.

Ivan Steenkiste and Mathieu Carre

Ivan Steenkiste and Mathieu CarreGaston Adier, the mayor of Carling, France, regularly takes schoolchildren to Danny Wilson’s grave, to tell his story, to remember his service and sacrifice. He also tells them about Dan Wilson’s family in America, who are glad that French schoolchildren know about the young Iowa farmer who became a P-38 pilot.

Gaston Adier is on the right in the back row.

Gaston Adier is on the right in the back row.One early morning during Memorial Day weekend, I won’t be surprised if a photo from France is waiting, reminding me that the Americans who pledged their lives to help liberate Europe from tyranny aren’t forgotten.

That Danny Wilson from Dallas County, Iowa, is not forgotten.

Hours later, as our Earth spins in space, rites will be held in Violet Hill Cemetery in Perry. Legionnaires will remember another brother, Junior Wilson, who was killed in Texas when the engine of his fighter plane exploded in formation training

They will also pay tribute to Dale and Daniel Wilson, whose cenotaph sits just north of their brother’s in Violet Hill Cemetery. Each Memorial Day Legionnaires mark the graves with small American flags, and red paper poppies with sprigs of evergreen.

The red poppy has been a symbol of war losses since Dr. John McCrae wrote the poignant poem “In Flanders Field” during the First World War. Crepe paper poppies are offered for donations for wounded veterans. For decades, Leora Wilson, with her compelling connection to the victims of war, was a favorite poppy lady in Guthrie Center, Iowa.

Memorial Day is set aside once a year to reflect on and honor our war casualties. Take your children to a ceremony in your local cemetery, explaining to them why it matters. Visit a Freedom Rock and talk about why those depicted are honored. Give a donation for a red paper poppy–for remembrance.

Memorial Day observances will be held in twenty-six American military cemeteries around the globe, with nearly 125,000 graves, including that of young Iowan Daniel Wilson. Those cemeteries also display panels with names memorialized of more than 94,000 still missing in action, lost, or buried at sea, including Dan’s brother Dale.

We here at home must not forget their service and sacrifice.

Leora’s Letters: The Story of Love and Loss for an Iowa Family During World War II remembers the story of the Wilson family. Autographed copies are available by mail from independent Beaverdale Books in Des Moines: (515) 279-5400