Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 43

October 12, 2020

Enough

The streets of my small New England town are full of lawn signs. Many of them say "Black Lives Matter." Many of them promote candidates for local school committee. (That race has gotten heated, since not everyone is happy with how the school committee managed decisions about pandemic schooling.) And of course there are signs for candidates in less-local races, e.g. the presidential race, though none quite so elaborate as the Biden-Harris sign made out of hay bales on a nearby farm that an arsonist torched. And doesn't that just feel like a metaphor for American civic discourse?

But I've been intrigued by the one that simply says "Enough." It's on a block with a bunch of political signs, so the first several times I saw it, I read it as a commentary on this endless election season. Enough with this administration and its gaslighting. Enough with talking heads and pundits, predictions and and polls. Enough with it already. Let's vote and be done. (Well. This year it may be more like "vote, and then spend a month or more navigating false claims of voter fraud and lawsuits over systemic voter disenfranchisement." But whatever.) Enough! Would that it were over already. We've had enough.

I suspect it's how all of us are feeling about the pandemic, too. Enough of COVID-19, and horrendous newspaper headlines, and refrigerator truck morgues, and bleak statistics, and the politicization of face masks, and lies about it being a "plandemic." Even a single death is too many; over a million is almost unimaginable. And countless more remain alive but sick. We all wish we could be done. (Of course, we're not done. So we're still masking, socially-distancing, washing our hands. But I know it wearies me; surely it wearies all of us.) Enough! Would that it were over already. We've had enough.

But the round of Jewish fall holidays drew toward their close, I realized there's another way to read it. Maybe it means: we are enough. What we have managed to do is enough. Even if we don't feel like we're doing a "good enough" job: if we're making it through this year, that's enough. We need to be gentle with ourselves. Don't fault ourselves for not learning a new language or writing the next great American novel during a massive global health crisis coinciding with enormous anxiety about the future of democracy. Whatever we're managing -- emotionally, spiritually, let it feel like enough.

Updated to add: I've just learned that the "enough" sign is intended to be a message against local police and racial equity work. I don't agree with that stance, and I will continue to creatively mis-interpret the sign when I drive past it.

October 11, 2020

A Simchat Torah like no other

I think my cat was perplexed. He has grown accustomed to me leading services from the dining room table: the laptop, my microphone, perhaps a pair of Shabbat or festival candles lit on the table beside me, lots of singing.

I think my cat was perplexed. He has grown accustomed to me leading services from the dining room table: the laptop, my microphone, perhaps a pair of Shabbat or festival candles lit on the table beside me, lots of singing.

These days when I daven from the table, he looks up briefly from his favorite perch on the cat tree and then returns to napping. But he has never seen me dance around the room holding a big metal-bound Tanakh encrusted with gems.

I don't have a Torah scroll at home, so I danced with the big metal-bound Tanakh that used to belong to my parents. I waltzed with it; I spun around in circles with it; I danced with it in a circumnambulation of the room; I cradled it like a baby in my arms.

Seven songs, seven poems, seven hakafot. Evoking the seven days of the first week, and the seven "lower sefirot" or qualities that we share with our Creator from lovingkindness to boundaries and strength all the way to presence and Shechinah.

I thrilled to the secret heart revealed when we go from the end of Torah directly to her beginning, from loss to starting over, from lamed to bet. I opened my Tanakh to a random word and from that word I gave myself a blessing.

And then I went to bed, and I slept the sleep of the overtired rabbi and elementary school parent who could finally relax into knowing that the work of this long, challenging (and this year, pandemic-unprecedented) holy season was done.

October 5, 2020

Lessons in letting go

"Mom, did you know that there are monks who spend months making really intricate sand mandalas and then when they're finished, they blow the sand away, because nothing lasts forever?"

My son says this to me on the first morning of Sukkot. I can't make this up. My d'varling for that morning, which I've just printed out, begins "Sukkot; festival of impermanence..." And here he is, telling me earnestly about sand mandalas.

"I did know that," I say. "Hey, can you think of any spiritual practices we have as Jews that are kind of similar to that?"

His eyes are a study in uncertainty.

"Where we make something beautiful and then let it come apart?"

"Wait a second," he says, and I can see the lightbulb going on. We've just spent four days building our sukkah, procuring fairy lights to illuminate it, and adorning it with all of his favorite sparkly decorations. (He even made a video about it.)

"I'll give you a hint. We build a little house and cover it with decorations. And over the course of the week the cornstalks dry out and the decorations fall down and at the end of the week we take it all down."

"Because nothing lasts forever?"

I nod.

"I wish our sukkah could last forever," he says, wistfully.

"If it did, we'd probably stop noticing how beautiful it is," I point out.

Two days later, we're in the car on the way to the elementary school for the first time in twenty-seven weeks. He is in an afternoon fifth grade cohort that will go to school four afternoons a week while infection rates remain low.

I drop him off curbside. He is wearing the mask he picked for the first day of hybrid school, carrying his school-issued Chromebook and a water bottle that will stay at school and some extra hand sanitizer for good measure.

As I watch him walk away, my heart seizes. Infection numbers here are low right now. I trust that our local elementary school is taking wise precautions. I know that he is going to be fine. But it still feels wrenching to let him out of my sight.

I return home, open up Zoom, and spend my Monday rabbinic office hour in our sukkah. A few of the decorations have fallen down. The cornstalks on the roof are beginning to dry out. The "it's not easy being green" etrog poster is now on the floor.

I sit inside our little homemade sand mandala of tinsel and schach. I remind myself that this pang isn't new. It just feels sharper right now because the pandemic has so unaccustomed me to letting him go.

October 1, 2020

Joy to fuel our building - a d'varling for Sukkot

Sukkot: festival of impermanence, festival of joy even in vulnerability. We build sukkot to remember our ancestors' harvest traditions; to remember the flimsy sukkot in which we dwelled after leaving Egypt; to remember the cloud of glory that protected us in our wilderness wanderings. Sukkot asks us: can we feel protected by God's presence even now, even in a flimsy little house that lets in the rain and the wind?

Sukkot: festival of impermanence, festival of joy even in vulnerability. We build sukkot to remember our ancestors' harvest traditions; to remember the flimsy sukkot in which we dwelled after leaving Egypt; to remember the cloud of glory that protected us in our wilderness wanderings. Sukkot asks us: can we feel protected by God's presence even now, even in a flimsy little house that lets in the rain and the wind?

That's always the question at Sukkot. What does it mean to feel safe and protected? What does it mean to build structures -- whether physical or spiritual -- knowing that nothing we build lasts forever?

On the physical front, this year there may be a paradoxical sense of safety in the sukkah because a sukkah is as well-ventilated as any space can be. It has to be, in order to be kosher. A sukkah can't be airtight with a solid roof. The roof needs to let moonlight and raindrops through. In these covid-19 times, this flimsy sketch of a room in the fresh air of the great outdoors is the safest place to breathe.

In part through the very fact of what a sukkah is, Sukkot asks us to grapple with impermanence. As soon as we put on the (purposely insufficient) roof, the roof starts to come apart -- the cornstalks dry up, the palm fronds or branches wither. "Emptiness upon emptiness," as we read this morning in Kohelet. Nothing that we can build lasts forever.

And Sukkot asks us to find joy in the midst of impermanence. One of this holiday's names is Zman Simchateinu, the Time of Our Rejoicing. How can we rejoice in a little temporary house where rain gets through the roof? We might as well ask: how can we rejoice in fragile human bodies that we know will someday die? And my answer is: how can we not?

Early in the pandemic, my friend Cate Denial reminded me that life doesn't go on "pause" while we're sheltering-in-place. This is the life we have. Right now it may be more constrained than we want it to be, for pandemic reasons -- but it is still life, and we need to live it, not sleepwalk through our days waiting for the pandemic to be over.

I think of that teaching often, and it feels deeply relevant to Sukkot. This little temporary house is a metaphor for human life. It's fragile. It's vulnerable. It's not forever. But as Cate taught me, this is the life we have -- and the time to cultivate joy is not in some unimaginable future when everything broken is repaired, but here and now.

Sukkot reminds me to grab joy with both hands, wherever I can find it. In my morning cup of coffee; in the scent of the etrog, sharp and stirring; in the light of the full moon. In the voices and faces of friends, even when the only safe way to see them is on Zoom. In the melodies of our prayers. In the rhythm of weekday and Shabbes.

These are quotidian joys, but they are real, and they can be sustaining. To be sure, the existence of these joys doesn't negate the difficult realities of this moment. One million dead to covid-19 around the world so far. Credible threats of election violence and voter intimidation. Fears that our democracy might be as fragile as this flimsy sukkah.

So during chag we cultivate joy, and we let that joy fuel us and strengthen us to do the rebuilding work that our world so desperately needs. Maybe this year that rebuilding work means textbanking or phonebanking to help eligible voters register to vote, or volunteering as a poll worker. Those actions help to build our democracy.

Or maybe you feel called toward something more tangible... like chopping onions for the Berkshire Food Project's grab-and-go meals, because need has tripled since the pandemic began. Helping to cook the meals that feed our hungry neighbors is a mitzvah that comes right out of Torah -- and it's an action that helps to build our community.

Sukkot invites us to cultivate joy that will sustain us in this work and more. Sukkot teaches us to seek joy in the full moon even though we're also vulnerable to the falling rain. Sukkot teaches us to seek joy even as we recognize the world's brokenness and work to fix it. Sukkot invites us to remember that this is the life we have, and our job is to live it.

This is my d'varling for Shabbat Sukkot (cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.) Image: the CBI sukkah this year.

September 24, 2020

Wake Up - a d'varling for Shabbat Shuvah

כְּנֶ֙שֶׁר֙ יָעִ֣יר קִנּ֔וֹ עַל־גּוֹזָלָ֖יו יְרַחֵ֑ף יִפְרֹ֤שׂ כְּנָפָיו֙ יִקָּחֵ֔הוּ יִשָּׂאֵ֖הוּ עַל־אֶבְרָתֽוֹ׃

Like an eagle who rouses their nestlings, gliding down to their young, So did God spread God's wings and take [us], Bear [us] along on God's pinions. (Deut. 32:11)

This verse from this week's Torah portion, Ha'azinu, leapt out at me this year. The metaphor of God bearing us on eagles' wings, lifting us out of slavery to Pharaoh and out of our constricted places, is not a new one. But what struck me here was the word יעיר, to arouse or to wake up.

Rashi says this image is meant to evoke an eagle who doesn't want to scare its nestlings, so the eagle flaps its wings a few times before coming in to the nest, to wake the young ones up and ensure that they feel strong enough to receive the eagle's coming.

Later in the passage, Rashi says an eagle carries its young on its wings rather than in its claws, because the eagle reasons, "if there is an arrow, better the arrow should pierce me than pierce my young" -- the eagle protects its young, and that's the quality of love that God has for us.

I love the idea of God carrying us on vast eagles' wings, seeking to protect us and uplift us. But even more than that, this year, I'm moved by this language of awakening or arousal.

God's love for us is both protective and a little bit pushy. Torah here imagines God carrying us and keeping us safe -- and also nudging us to wake up.

Just as the shofar's call nudges us to wake up.

Just as this whole season nudges us to wake up.

The commentator known as the Or HaChayyim agrees: "Moses uses the simile of the eagle to show that just as the eagle rouses its young first, so G'd rouses the children of humanity to warn that we have to put our spiritual house in order." This is the season for doing exactly that.

Shabbat Shuvah is our wake-up call. God is the eagle hovering over the nest, flapping mighty wings to urge us to rise up with all our strength and to do what's right. God is the shepherd taking account of each of our lives as we pass beneath the staff, reading the Book of Life that we have written with our choices. God is in the shofar's call -- which sometimes sounds like triumph, and sometimes sounds like anguish -- begging us to wake up.

Not because Yom Kippur begins tomorrow night, although it does.

But because the world needs us to wake up. Our community needs us to wake up. Our souls need us to wake up.

To what do we need to wake up at this moment in our spiritual year?

To what do we need to wake up at this moment in our national life?

Much is going to be asked of us in this new year. We need to wake up. We need to strengthen our souls and strengthen our resolve to stand up for what's right.

God is here to wake us up. To rouse us from our sleep. To arouse in us the yearning to do what's right. To enflame our hearts with a passion for righteous acts and justice: on a personal scale, on a communal scale, on a national scale.

Will we be woken?

This is the d'varling I offered on Shabbat Shuvah (cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

September 19, 2020

The Courage to Stand Up, With Love

I gave my sermon "live" on Zoom in realtime, and also pre-recorded this version to go live on my blog around the same time I was offering it at Zoom services. If you want to watch the video, it's embedded above and is here on YouTube. Or, if you prefer to read it, you can read on, below...

Do you remember how you felt when you heard the news about the Pittsburgh synagogue shooting?

I remember feeling shock and horror and disbelief. I remember feeling grief. I remember our synagogue sanctuary filled with members of the Northern Berkshire community who came together for a vigil in grief and remembrance.

And I remember coming to shul the very next Shabbat -- with a prickle of anxiety running through my veins -- and stopping short when I saw the "graffiti love-in" all around our front door.

I knew it was coming. Someone I did not know had reached out to me earlier that week, saying that a group of non-Jewish allies wanted to organize a show of support for us. They didn't want to surprise us in a way that would compound our feelings of un-safety, so they asked first.

But even though I knew they were doing something, I couldn't picture what it would be. I didn't know how it would feel to drive up to our shul one week after the Pittsburgh synagogue massacre and be greeted with chalk art and signs and cards and banners proclaiming that the North Adams community values us and wants us to be safe and wants us to be here.

Their gift made me weep tears of joy -- because we are seen, and cherished, and uplifted. And not just by other Jews but by non-Jewish people, by people who are not part of our community or part of our covenant. But they saw that we were afraid, and they stood up for us and said, "you matter; we want you here; we've got your back."

There's a reason that the most oft-repeated commandment in Torah instructs us to love the stranger for we were strangers in the land of Egypt. Thirty-six times Torah tells us to love the stranger, the immigrant, the refugee, the vulnerable population, because we know how it feels to be in those shoes. The instruction is in the plural: v'ahavtem et ha-ger, y'all shall love the stranger. This isn't an individual commandment: it's a communal mitzvah. Together, we love the stranger because we know how it feels.

We know how it feels.

And that's why I have two signs on my condo front door. One is a blue mogen David that says "Chai Y'all!" I want it to be clear to anyone who drives by that I am Jewish, I am here, I am visible, and I am welcoming! (And I say y'all.) The other is a sign that says Black Lives Matter.

I know that some Jews are uncomfortable with the Black Lives Matter movement because of real or perceived connections between BLM and pro-Palestinian sentiment. I empathize with that discomfort. And there are many intellectual conversations we can have about BLM and Israel / Palestine. But I believe that Jewish values call us to stand up for Black lives even if we feel some discomfort. We need to "de-center" ourselves, because right now this isn't about us -- it's about standing up for the victims of prejudice and violence. And that's work we do with our hearts and our souls, not just our intellect.

The Black Lives Matter movement is a grassroots coalition of many organizations, focused on saving the lives of Black people and people of color by changing how we do public safety and policing.

The vast majority of people protesting or holding vigils or putting signs on their lawns are not thinking about international issues (including the Middle East). They're thinking about George Floyd who died gasping "I can't breathe" to the officer kneeling on his neck. They're thinking about Eric Garner who died gasping the same thing to the officer holding him in a chokehold. They're thinking of Tamir Rice, killed at twelve because an officer mistook his toy for a gun. They're thinking about Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery and Atiana Jefferson and Stephon Clark and Botham Jean and Philando Castile.

And maybe they're thinking about the Greensboro Four, brutally beaten for daring to sit at a Woolworth's lunch counter. Or Emmett Till, lynched because someone thought he smiled at a white woman. Or the countless Black souls ripped from home and brought to this nation in chains. Or the reality that Black people are dying of covid-19 at rates far higher than white people. Or 400 years of communal experience and communal trauma showing them just how little Black lives have mattered on these shores.

Just as we need non-Jewish allies to stand up for us when there are attacks on Jews, Black people in this country need allies to stand up for them when they are under attack.

And it's not an either/or. There are many Black Jews who feel keenly both of these forms of oppression, both antisemitism and racism. Not in our little rural community, but in the broader Jewish community. We owe it to them to stand up for them.... and we need to stand up for non-Jewish Black lives, too.

Rabbi Margaret Frisch Klein, who serves as a police chaplain, expresses the needs of this moment with a policing metaphor from Sergeant Dan Rouse: "If we get a call about a domestic violence incident [at a particular address], we don't stop at every other house along the way. If you go to a fundraiser for breast cancer, you don't stop at every other fundraiser along the way and say all cancers matter. Right now, Black lives are hurting." That's the call we need to answer.

Remember how it felt to see those signs of support on our synagogue doors? I hope that's how it feels for Black people to see a Black Lives Matter sign. It signifies that someone who sees their trauma and their fear is willing to stand up in the name of their safety. It means that someone who maybe doesn't look like them nevertheless wants for them basic human rights and human dignity.

I mentioned earlier the discomfort that I know some of us feel around the connection between Black Lives Matter and support for the Palestinian cause. I honor the discomfort, and I understand it. And... I think our discomfort is part of our spiritual work in this time of American reckoning with institutionalized racism. I think part of our work as white-skinned Jews is saying: what you're enduring is untenable and we stand with you against it, and any disagreements we might have about politics can wait.

We need to stand up for each other even when we feel discomfort. Safety and basic human dignity are the birthright of every human being, no matter what -- or at least, they should be, and if they're not, then we have work to do. And standing up for one another's safety and dignity is a moral imperative more important than any political disagreement.

In her book Braving the Wilderness, social scientist Brene Brown notes that the English word courage is related to the French coeur: heart. Having courage means having heart. Having courage means listening to the heart and acting from the heart.

It takes courage to stand up for our fellow human beings when they are under threat. It takes courage to stand up and say: I will fight for your human rights and your dignity and your right to live safely. Even if your skin looks different from mine. Even if your politics are different from mine.

Standing up for Black lives is an act of hope that we can build a better America, an America where everyone truly enjoys the rights that our Declaration of Independence enumerates, among them life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Of course, when that Declaration was written, the only people who merited those rights were white men! Thank God our laws no longer enshrine those injustices. But those injustices persist, and our work is not complete.

Standing up for Black lives asks us to confront our own stuff that might get in the way. It asks us to do our own inner work, and to learn how to be actively antiracist -- to resist and change the subtle and pervasive racism that's baked in to our nation's history and its present. That kind of inner work is exactly what this season of teshuvah, repentance and return, is for.

Remember the kindness our non-Jewish North Adams neighbors extended to us after Pittsburgh? Standing up for Black lives is how we can "pay it forward."

Torah asks us to love the stranger, because we were strangers in the land of Egypt and we know how it feels. We know how it feels! And we know how it feels when our neighbors stand up for us. May our knowledge move us to stand up for Black lives with hope and courage and heart.

For further reading: from the Jewish Council on Public Affairs, Black Lives Matter, American Jews, and Anti-Semitism: Distinguishing Between the Organization(s), the Movement, and the Ubiquitous Phrase [pdf] 2020.

This is my sermon from Rosh Hashanah morning (cross-posted to my From the Rabbi Blog.)

September 18, 2020

Holy at Home, With Love

Here's a recording of my sermon if you'd rather watch it than read it. (It's here on YouTube.) Or, read below...

Not quite two thousand years ago, the Roman army sacked the second Temple.

Not quite two thousand years ago, the Roman army sacked the second Temple.

That's a tough place to begin my words to you on erev Rosh Hashanah! But in a way, it's where tonight's story begins.

The Temple was the center of our universe. It was our axis mundi, the holy connection point between this world and God.

And then it was destroyed.

Judaism could have ended when the second Temple fell. The Temple was the site of our daily offerings to God. Our whole religious system was built around it! We could have given up hope. That could have been the end of the Jewish people and the Jewish story.

Thank God, it wasn't. That destruction sparked a paradigm shift in how we "do Jewish." Jewish life become portable, something we could take with us into every corner of the globe. The center of Jewish life became the synagogue, which aspires to be a beit knesset (house of community gathering), beit midrash (house of study), and beit tefilah (house of prayer) all in one.

And, some would say: the center of Jewish life became the Shabbes table. Tradition teaches that the table where we celebrate Shabbat each week is a mikdash me'aht, a tiny sanctuary. The home table replaces the altar of old; the twin loaves of challah replace the doubled Shabbat offerings on that altar; and holy space becomes... wherever we make it.

Never has that seemed so true to me as it does right now... or as necessary.

Six months ago when we began sheltering-in-place to stop the spread of covid-19, we hoped that a few months of disciplined quarantine would quell the pandemic and that we would be back together again in person by Rosh Hashanah. Instead here we still are: making Rosh Hashanah in our homes, keeping each other safe by staying physically apart.

Our synagogue is still a house of gathering, a house of study, and a house of prayer... and right now all three of those houses are our own houses. Our challenge is learning how to create sacred space here at home where we are. Learning how to create community together when we can't embrace or sing in harmony. Learning how to find holiness in our everyday spaces, and how to feel community connections even when we're apart.

It turns out that Judaism has some spiritual technologies designed for exactly these purposes. The Shabbes table is one of them -- a white tablecloth, maybe some flowers, the Shabbes candles burning to remind us of the first light of Creation and the light of revelation at Sinai. These are tools for making sacred space.

Another is tzitzit, wearing fringes on the corner of our garments to remind us of the mitzvot -- that's a tool for mindfulness, and for community connection. Our community's tradition of making bracelets each year serves the same purpose. For several years now we've printed silicone bracelets for the Days of Awe. This year's bracelets read:

Love ♥ Ahavat Olam ♥ Rebirth ♥ Courage ♥ Resilience ♥ Teshuvah ♥

There are two transliterated Hebrew words or phrases. One is teshuvah -- repentance, return, turning ourselves in the right direction again. That's the fundamental move of this season, and that word has been on our bracelets every year we've gotten them printed. The other is ahavat olam, a phrase from daily liturgy. It means unending love, or forever love, or eternal love. Our tradition tells us that God loves us with ahavat olam.

For some of us "the G-word" is a stumbling block. Which God, what God, what do we mean by God -- God far above, God deep within, Parent, Sovereign, Creator, Beloved? And for some of us "the L-word" might be equally challenging. The word love gets so overused it becomes almost meaningless.

"Wait 'til you hear this song, you're going to love it!"

Fiddler on the Roof: "Do you love me?" ("Do I what?!")

My son would tell you that he loves Minecraft and plain vanilla soft-serve. That's not the same thing I mean when I tell him that I love him.

When I say I love my child, I'm talking about something profound and soul-expanding. If "I love ice cream" is a five on the love scale, maybe "I love my child" is 500... and ahavat olam is infinity. And I think in this pandemic year, we need connection with that sense of infinite ahavat olam more than ever before.

That's why love -- ahavat olam -- is our theme for this year's Days of Awe. And our four cups tonight at our Rosh Hashanah seder represent different facets of love.

The first cup was for creative love. One of my favorite teachings holds that God created the universe of love, because God yearned to be in relationship with us.

Our second cup was for courageous love. Love asks us to risk disappointing each other. To risk speaking difficult truths. To act with courage and integrity, even when we feel as though we're in the wilderness.

Our third cup just now was for resilient love. In this season of teshuvah, love asks of us the resilience to honestly turn our lives around.

And before Mourner's Kaddish we'll bless a cup of tears, evoking love that remembers.

Tonight we're celebrating Rosh Hashanah while sheltering-in-place. We're making our home spaces holy, and learning how to feel connected as a community from all the various places where we are. These are actions that we take to protect each other, to prevent viral spread, to care for those who are medically vulnerable and immunocompromised. They're actions we take out of love.

Our bracelets this year also say rebirth: because tradition says that today the world is reborn, because this season is our chance to begin again. They say resilience, because the new year calls us to resilience; because the pandemic calls us to resilience; because authentic spiritual life calls us to resilience. And they say courage, because starting over takes courage. And living during a pandemic takes courage. And as Brene Brown reminds us, "courage" has its roots in the French word coeur: heart. Courage takes heart. Which brings us back once again to love.

May these Days of Awe strengthen our resilience and our courage and our heart. May they help us find holiness at home, here in all the physical places where we are. And may we emerge from this sacred season more able to give and receive love in all the ways that our world most needs.

L'shanah tovah.

This was my brief d'varling from tonight's Erev Rosh Hashanah Seder (cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

September 15, 2020

Shine

Silverware, soaking.

It's the week before Rosh Hashanah. I have a million things to do, there's never been a High Holiday season quite like this pandemic one, and I'm... polishing silverware. Somewhere in the afterlife my mother is cheering, "Attagirl!"

A few days ago I was looking for a photograph of apples and honey to put on my synagogues's Facebook page. I found one. And I also found photos from seven years ago, when mom was well enough to travel and my parents were here for the holidays.

There are photos of my mom (of blessed memory) cooking in the kitchen of my old house. She managed somehow to look elegant even in a borrowed apron wielding a knife over a head of cabbage! And there is a photo of my dad polishing the silver.

Because my mother was not pleased with the amount of tarnish on my silver, so she asked Dad to polish it while she cooked. I remember being half-amused and half-embarrassed. I remember thinking: well, I guess it gives him something to do.

Mom is gone now. This will be my second High Holiday season without her in this world. I'm endlessly thankful that through the alchemy of mourning, my once-sharp grief has transmuted into gratitude and fond remembrance, at least most of the time.

She'll still be at my table. I have her monogrammed white napkins, which I used at our little family seder, and which I will use again on Friday night. I have her silver napkin rings, each one different from the others. And I have her wedding silver.

It's my everyday silverware now. When I moved out, I took Mom's silver with me, and I decided to use it for everyday. I didn't want to spend money on another set of flatware, and besides, what's the point of having beautiful things if not to use them?

But my silverware is once again tarnished. Mom would not be pleased. So in between testing my high holiday slide decks on different devices, I'm lining my roasting pan with tinfoil and filling it with silver and boiling water and baking soda.

And then I'm rinsing away the slippery baking soda-water and patting the pieces dry with torn pieces from a soft old t-shirt. Rubbing their tarnish away and returning them to their places in the silverware drawer, ready once again to shine.

It feels like a metaphor for the work of the season. (Early-autumn cleaning always does.) Finding our tarnished places and cleaning away the grime left by the old year's misdeeds so that our souls can be ready once again to shine.

September 14, 2020

Liturgy for Sukkot in times of covid-19

Before Tisha b'Av, I gathered a group of liturgists to collaborate on a project that became Megillat Covid, Lamentations for this time of covid-19.

In recent weeks we've gathered again -- in slightly different configuration -- to build something new for this pandemic season: a set of prayer-poems for Sukkot and Simchat Torah, which we've titled Ushpizin. That's the Aramaic word for guests, usually used to refer to the practice of inviting ancestral / supernal guests like Abraham and Sarah into our Sukkah... though this year, what does it mean to invite Biblical guests when many of us don't feel safe inviting in-person guests? That's the question that gave rise to the project.

The prayers / poems that we wrote arose out of that question and more. What does it mean to find safety in a sketch of a dwelling in this pandemic year? With what, or whom, are we "sitting" when we sit in our sukkot this year? What about those of us who can't build this year at all? And what can our Simchat Torah be if we are sheltering-in-place, or if our shul buildings are closed, or if we are not gathering in person with others?

For Megillat Covid, we each wrote a piece and then I collected them. This time our creative process was different. Four of us collectively wrote nine pieces, and then we met to workshop them and revise them together, in hopes of creating not just nine individual prayers but a whole that would be more than the sum of its parts. And then we wrote the tenth prayer-poem together as a collaboration... and Steve Silbert offered a couple of sketchnotes, too.

You can click through to Builders Blog to read excerpts from our ten poems and to download the whole collection as a PDF, and I hope you will -- I'm really proud of this collection, and humbled and honored to have convened the group that brought it to life.

September 10, 2020

One Heart: Lessons in Love from Jewish Cuba

I gave my sermon "live" on Zoom in realtime, and also pre-recorded it to go live with this blog post around the time I was offering it. If you prefer to watch the sermon, it's above (and here on YouTube.) If you prefer to read it, the text appears below.

When I gave the sermon tonight I began by noting that every year I seem to write at least one extra high holiday sermon -- a sermon that I write and then don't give for some reason. This year that extra sermon was Oops, We Did It Again: on choices, momentum, and change. I wrote it, and then I realized: y'all don't need me to tell you about the pandemic or the climate crisis or antisemitism. You know those things already. That won't take us anywhere new or open our hearts tonight. So I wrote and offered this sermon at Kol Nidre, instead. (And if you want to read the other sermon, now you can -- it's linked above.)

The first things I saw on the tarmac at José Martí international airport were palm trees and military vehicles. That's when my friend Rabbi Sunny, the head of Cuba America Jewish Mission, reminded us not to photograph soldiers -- in fact, not to photograph anything at all until we had cleared the airport, just to be on the safe side. Right, I thought. I'm in a Communist country. Note to self, don't photograph the army.

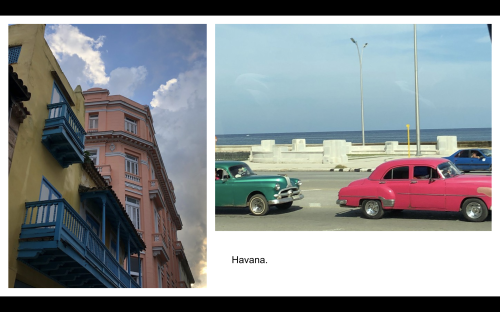

Last November, with Temple Beth-El of City Island in the Bronx and with Cuba American Jewish Mission, some CBI members and I spent ten days traveling around Jewish Cuba, from Havana to small cities and towns across the countryside.

Everywhere we went, we brought bags of medical supplies: everything from aspirin, vitamins, and prescription medications to anti-fungal cream and tubes of toothpaste. The synagogues there run pharmacies, and they make these pharmacy supplies available to anyone in need, whether or not they are Jewish. When we arrived, there had not been a mission like ours in six months, and their pharmacy shelves were close to bare.

Havana is incredibly beautiful. The sea crashes up against the wall on the Malecon, the main thoroughfare. One day we saw people clustered at that wall, throwing roses into the sea in remembrance of Camilo Cienfuegos, who died in a plane crash over the sea after the revolution. The sunlight was golden on stately buildings with sometimes cracking plaster and peeling paint. There was extraordinary music, everywhere. Young musicians there learn music on the state's dime; they play in bands and on rooftops and in the streets. It's facile to say that when one lives with hardship, the gifts of music and of spiritual life are more palpable. But I kept having that thought anyway.

As we moved deeper into the countryside, we started to encounter people who would come up to us with a hand out. They weren't asking for money. They were asking for soap or shampoo. Everyone in Cuba is guaranteed health care, which is pretty extraordinary. But once we left the city for the provinces, a lot of people didn't have soap. "Rite Aid or Walmart is like a fantasy to us," said one person who had traveled abroad and had seen American big-box stores and pharmacies.

I've thought of that often since the pandemic began. And when Stop and Shop in North Adams started running out of things, early-ish in the pandemic -- you remember: for a while there, we couldn't buy flour, or dried beans, or toilet paper -- I thought of the mostly-empty shelves in the Cuban stores we visited.

In the spring when here in the US we faced simultaneous food shortages and produce rotting in the fields, I remembered stories of Cubans going hungry after the Soviet Union fell. They told us about eating grass to try to fill their bellies while citrus fruits rotted in the fields because there was no gasoline to transport them. And I thought of how our Cuban cousins must be doing now, as the combination of pandemic and trade embargo keeps their shelves even emptier, and keeps their Jewish cousins from abroad away, with our tzedakah and our care and our desperately-needed duffel bags of aspirin and soap.

And yet when I think of the Cuban Jews we met last fall, what I remember is not what they didn't have, but what they did: their warmth and their kindness, their connectedness and their pride. I remember the music, everywhere. I remember their beautiful synagogue sanctuaries: the Patronato in Havana, which seemed plucked right out of the 1960s just like the classic cars that serve as taxis, and the beautiful little painted synagogue in Santa Clara where we celebrated the coming-of-age of a Cuban bat mitzvah -- rebuilt with tzedakah from the Cuba America Jewish Mission and travelers like us.

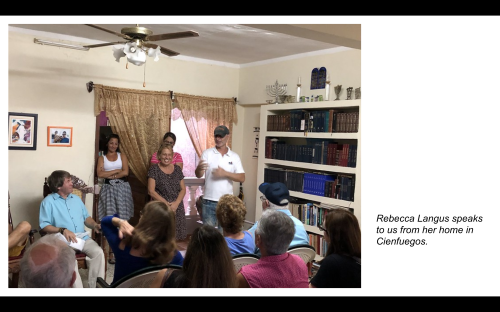

Most of all, I remember their love. One day we visited Rebecca Langus in the provincial city of Cienfuegos. The entire Jewish community there is eighteen people. They meet for services in her living room, on white monobloc plastic chairs that otherwise sit stacked on her tiny mirpesset next to her laundry line. She teaches the Hebrew school, which is currently three children, using books donated by Jewish visitors from abroad, like us. She works tirelessly to keep her community alive. After her prepared remarks, the four rabbis on the trip chatted with her. We asked her how she does it, and what gives her hope.

"Everything I do, I do for love," she said simply. That could not have been more clear: her love for her community, for our shared traditions, for Jewishness itself, shone from her like light.

She told us that when they meet for Shabbat, they always have a minyan. I thought: there are only fifteen Jewish adults in this city of 150,000. Two-thirds of the Jews in town need to show up if anyone is going to say kaddish. And... they do. And if there is a fuel shortage, which often there is, they catch a ride on a donkey-pulled cart, or they walk. Because of love: for our traditions, for community, for each other.

Love brought the Jews of Cuba together to celebrate a bat mitzvah while we were there. Many walked miles, some for days, because new US sanctions had contributed to another fuel shortage. Our tour bus was able to secure fuel, but most locals weren't. So they walked. Because it was worth it to them to be there for each other.

I felt that same extraordinary sense of community love on our final stop in Cuba, the Spanish colonial city of Camagüey. That community meets in a rented house, where they have a beautiful tiny sanctuary with a hand-painted ark, and a little social hall where we gathered to learn from them and to share songs together. There are 32 people in the Jewish community there. We sang "Am Yisrael chai" -- the people of Israel yet lives! -- which took on a new poignancy there, where for so long the state forbade the practice of any religion at all.

That visit to Camagüey was our last day of the trip, and after a meal with the community there, I listened as my friend and colleague Rabbi David -- who is fluent in Spanish -- asked a young man why he has chosen to stay in Cuba. His answer: sure, he could go anywhere. But the closeness of the Cuban family and community is precious. It is worth more than whatever money he could earn if he were to decide to leave.

Ten days does not make me an expert on the Jews of Cuba. (I suspect that ten years would be insufficient.) But our trip still resonates in me. The Jews I met in Cuba inspired me with how proud they are to be Cuban and to be Jewish. They inspired me in how they show up for each other. Even in a place where for so long it was illegal to practice any religion at all. They inspired me with their love for our traditions, their love for community, their love of country, their love for each other.

The Jews of Cuba live with profound hardship. That was true a year ago; it is even more true now. And yet... when the pandemic began to rage in the US, they reached out to me via Facebook to make sure that we were okay. Because their love and care flows so naturally, even toward we who have so much.

Tonight they too are hearing the words of Kol Nidre, words that release us from the vows we won't be able to live up to. But I don't want to be let off the hook for my promise to keep our connections alive across borders and differences. Communist or capitalist, Cuban or American, rich or poor, we are part of one Jewish family.

Because of the pandemic, it will probably be a long time before we can gather together again in person in physical space. And... the pandemic also highlights how deeply interconnected we are, even when we're apart. Covid-19 spread around the world because the whole world is interconnected: what happens there has an impact here. What happens to me has an impact on you. This is a deep spiritual truth. It's also a practical one.

And covid-19 is also teaching us other forms of connectedness. Over these pandemic Days of Awe, we've davened with members of our community who live in other places... and with far-flung friends and family who maybe never felt connected with our little shul before. What if we keep all of these connections vibrant and alive in 5781? Imagine the strength and hope and courage we could share with each other through the pandemic winter that is coming. We can be there for each other as our Cuban cousins are there for each other -- and we don't have to walk miles to do it: our connectedness is as close as the click of a computer key.

For that matter, we can be there for our Cuban cousins, too. Rabbi Sunny tells me that right now it's almost impossible to send tzedakah to Cuba. As of this week, a wire transfer sent in July via Panama and Israel has yet to materialize, and a package of much-needed medicines has been missing for sixty days. But we can support the Cuba America Jewish Mission so that when it becomes possible to directly bring help to Cuba again, there are tzedakah dollars to bring.

Talmud teaches that all of Israel is responsible for one another. Our Cuban Jewish cousins live that truth -- not because it's in Talmud, but just because of who and how they are. This Yom Kippur, may we find uplift in the knowledge that under unbelievably difficult circumstances they are praying these words with us too. May we go the extra mile to be there for each other in community, as do our Cuban cousins. And may we find uplift in the knowledge that we share one tradition; that we share one heart; that love connects us all.

This is my Kol Nidre sermon (cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers