Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 39

February 19, 2021

Perseverance and the portable ark

"וְעָ֥שׂוּ לִ֖י מִקְדָּ֑שׁ וְשָׁכַנְתִּ֖י בְּתוֹכָֽם׃ / Let them make Me a sanctuary that I may dwell within them." (Ex. 25:8 - in this week's Torah portion, T'rumah.)

The word mishkan (the portable dwelling-place for God) shares a root with the word Shechinah, the divine Presence. We build sacred space so God will dwell in us. I talk about this verse every year, because I love it. But this year, what jumps out at me is its juxtaposition with what follows.

Immediately after this verse, Torah tells us to make an ark to hold the tablets of the covenant. Cover it with gold. Put rings on the sides, and poles through the rings. And keep it that way. The ark over which the divine Presence would rest needed to be ready to go at a moment's notice.

Wherever the people go, holy words and presence go with them -- which is to say, with us. As beautiful as the mishkan was (as beautiful as our beloved shul building is) God's presence doesn't live there. God's presence goes with us. Our texts and traditions go with us. Holiness goes with us.

Our ancient ancestors needed perseverance to make their way through the wilderness. I imagine that their perseverance was fueled, in part, by this verse and its assurance that God goes with us wherever we go.

After the Temple fell, our sages called the Shabbat table a mikdash me-at, a small sanctuary. I keep returning to that image during this COVID time. God's presence is with us at our Shabbes tables tonight. God's presence is with us when we bless and light candles together-apart, when we bless and break bread together-apart, when we daven together-apart.

The poles were kept in the rings of the ark to teach us that the life of the spirit goes with us wherever we go. God goes with us wherever we go. Holiness goes with us wherever we go. And like our ancient ancestors, we need perseverance to get us through.

Yesterday NASA landed a new robotic rover on Mars, named -- as you probably know -- Perseverance. Some of you may have watched on the news or online as NASA engineers got word that the rover had safely landed, and celebrated from afar.

I read in the Washington Post earlier this week that "Hitting the 4.8-mile-wide landing site targeted by NASA after a journey of 300 million miles is akin to throwing a dart from the White House and scoring a bull’s eye in Dallas." It's honestly incredible.

As is being able to see images from our neighbor planet in realtime. As is the dream that the science this little robot will do -- sampling regolith and soil, testing for microbes -- will bring us one step closer to someday landing human beings on Mars.

I hope I'm around to celebrate that day -- and to see how Judaism will evolve once it becomes interplanetary! Will Jews on Mars turn toward Earth to pray, the way we now orient toward Jerusalem? How will we navigate the fact that a Martian "day" is different from an earth day in calculating Shabbat?

(Although I haven't researched this, my instinct is to say that Shabbat should be every seventh day, local time, even if that means it's not coterminous with Shabbat on earth. But that's another conversation.)

I'm confident that when there are Jews on Mars, we'll figure out how to build Jewish there.... and that we'll find this week's Torah portion resonant when we do.

Because God's presence is with us when we shelter in place at home now. And God's presence will go with human beings to Mars someday. And the same spirit that enlivens our Shabbes tables here will enliven us there.

Holiness and hope aren't geographically limited. They go where we go. And the perseverance that got us through the wilderness is the same perseverance that will take us to the stars.

The poles stayed in the rings on the handles of the ark because God goes with us wherever we go.

As we approach one year since our awareness of the pandemic began, there's something poignant about the name of this little rover. Perseverance is the quality we need to reach that dream of human beings on Mars.

It's the quality we need to mitigate climate change and ensure safety and care for our fellow human beings -- especially in times of crisis like Texas is experiencing now. And it's the quality we need to make it to the other side of this global pandemic.

The Hebrew word for Perseverance is הַתמָדָה, which contains within it the root t/m/d, always. As in the ner tamid, the eternal light kept burning in the mishkan, the eternal light that burns now in synagogues around the world.

The ner tamid is a perennial reminder of divine Presence, and holiness, and hope burning bright. The ner tamid perseveres, as our hope perseveres, as our life of the spirit perseveres.

May we take hope and strength from the Mars rover Perseverance. May we find our own perseverance strengthened as we approach the second year of this pandemic. And may we feel the flame of hope burning bright within our hearts -- the holy sanctuaries where God's presence dwells.

This is the d'varling I offered at Shabbat services this evening (cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

February 17, 2021

A prayer in a casserole dish

I am making enchiladas for dinner. The recipe I use didn't come with me from Texas, but it could have. There's a Tex-Mex chili gravy (red enchilada sauce) made with a light roux, a ton of hot chili powder, some cumin and oregano and garlic and salt. This enchilada sauce tastes like the enchiladas I grew up eating. Every time I make it, it transports me.

This is the time of year when I would ordinarily be taking my kid back to my birthplace -- to see family, to breathe the air of where I come from, to enjoy Mexican breakfast at Panchito's and big fluffy Texas-sized pancakes at the Pioneer Flour Mill. In this pandemic year, there's no trip to Texas. The last time I was there was for mom's unveiling.

Knowing that most of Texas is suffering cold and snow and rolling power outages, making these enchiladas feels like a kind of embodied prayer. When I make challah on Fridays I sing while kneading the dough. Tonight I am praying for Texas as I simmer the chili sauce, as I dip the corn tortillas in oil, as I tuck each rolled enchilada into the baking dish.

I spoke with family there this morning, and texted with them again later in the day. Like most of Texas, they didn't have power or heat. Southern homes aren't build to keep out the cold -- they're designed to retain cool. A lot of Texans don't own warm winter clothes; why would they? Often at this time of year, it's warm enough to wear short sleeves.

I could talk about why Texas has its own power grid, or the outrage of wholly preventable tragedies, or the importance of a robust safety net and good infrastructure in all neighborhoods, or the climate crisis that inevitably feeds worsening weather patterns. Instead I'm rolling enchiladas and praying that somebody can get the power up and running again.

February 15, 2021

The lot of one year. (It's been a lot, this one year.)

Purim is almost upon us -- the last Jewish holiday that most of us celebrated in person last year, before the pandemic started keeping us apart. It's a tough anniversary. A year since we started staying apart to protect each other. It feels like forever. We celebrate Purim with costumes and masks -- masks, for sure, mean something different now than they ever did before. We celebrate topsy-turviness -- but what does it mean to do that when our whole world feels turned upside-down?

Those were some of the questions animating the members of Bayit's Liturgical Arts Working Group. I think you'll see them in our fifth collection of prayer and poetry and artwork, which we just released today. My main contribution (aside from convening the group!) is a poem about Esther and us, quarantine and saving lives and loss. I also wrote one of the short pieces in our seven-part "Last Purim" series, reflecting on what Purim was like "before covid," a year (or maybe a lifetime) ago.

For me I think R. Sonja K. Pilz's poems are the most poignant and powerful this time around -- the one about her baby thinking masks are ordinary, and the litany with the refrain of "twelve months / or more." But honestly, everything in this collection moves me, and I'm grateful to be collaborating and co-creating with this exceptional group of artists, liturgists, and rabbis. You can read excerpts and download the PDF here at Builders Blog: The Lot of One Year - Liturgy, Poetry, and Art for Purim 2021.

February 9, 2021

Fix

Things I cannot fix,

an incomplete list:

armed militias.

Global pandemic.

The grief of staying apart

and unbearable yearning.

Rage at insurrectionists

and anti-maskers.

Things I can fix:

lunch for my child.

This winter stew, meat

from the freezer

and dried mushrooms

plumping in hot broth.

Warm speckled rye dough

pliant beneath my hands.

February 6, 2021

The San Antonio Song

The turntable had been my sister's before it became mine. In my memory it is black and white and sleek, standing on one foot like a cross between a mushroom and a flying saucer, with a smoky dark plexiglass lid that lifted up so you could put the record down on the turntable.

The turntable had been my sister's before it became mine. In my memory it is black and white and sleek, standing on one foot like a cross between a mushroom and a flying saucer, with a smoky dark plexiglass lid that lifted up so you could put the record down on the turntable.

The stereo was dual-purpose, with an 8-track tape deck on the front side. I remember playing Barbra Streisand on 8-track, though I can't remember what else I had inherited on those big boxy cassettes.

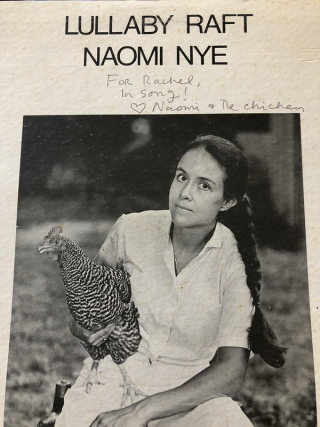

My record collection was slightly more expansive. An album of what I grew up calling Mexican polka (though now know as norteño); an LP of Strauss waltzes; Prokofief's Peter and the Wolf (narrated, I think, by Captain Kangaroo); Simon and Garfunkel's Bookends, Bob Marley's Exodus; James Taylor's In the Pocket; and Lullaby Raft, by my childhood poetry teacher, Naomi Nye. She had inscribed the cover of the LP to me, from "Naomi and the chicken."

The Naomi Nye LP recently came back into my possession. I don't own a turntable, so I can't listen to it now -- but as soon as I picked it up, I remembered the crackle of the needle in the groove and the sounds of her guitar.

I must have listened to the B side on infinite repeat, because 40 years later those are the songs I remember clearly: "When You're Not Looking," "Can't Complain," "The San Antonio Song." There's a lot to be said for a house and a bed...

As an adolescent I used to get desperately homesick at summer camp. (It started the summer I was eleven, at a camp in Wisconsin that just wasn't the right fit. The kids in my cabin teased me mercilessly, and after crying myself to sleep for a few weeks, I left the camp before the eight-week session was over. I struggled with homesickness for a few years after that.)

As an adolescent I used to get desperately homesick at summer camp. (It started the summer I was eleven, at a camp in Wisconsin that just wasn't the right fit. The kids in my cabin teased me mercilessly, and after crying myself to sleep for a few weeks, I left the camp before the eight-week session was over. I struggled with homesickness for a few years after that.)

This was one of the songs that would run through my head when I yearned the most for my home, the sound of my mother's voice, my four-poster bed with the forest-printed coverlet. I want to run back to your loving arms...

It's been more than a year now since the last time I visited San Antonio. In a normal year, I would take my kid there a few times a year to see my dad and my brothers. The last time I went, I went alone for the unveiling of my mother's headstone.

I promised my dad that I would come back soon with my son. A few weeks later, we started hearing about something called novel coronavirus. Soon we were sheltering-in-place to slow the spread. For a while I thought it would be safe to go back to Texas by summertime. Then it became clear what we were facing...

I don't want everything I write to become an elegy or a lament. This was supposed to be a light-hearted remembrance of an old record and my old record player! But all paths seem to lead to remembered loss, or to the ache of yearning for something that isn't yet possible.

To meet my father and brothers for Mexican breakfast at our favorite brunch joint in the old neighborhood. To visit my childhood home where my parents haven't lived in decades. To hug my mother who's no longer here. To hug my beloveds who are (thank God) still alive, but we can't safely touch.

February 5, 2021

Noodles and nostalgia

I copied the recipe off of a card I got at Zingerman's. It's for fettucine with tuna, white wine, and green peppercorns. I don't always have a bulb of fennel on hand, nor for that matter fettucine, but but oil-packed tuna and peppercorns and capers are pantry staples. I've made the dish often since the pandemic began.

I've only been to Zingerman's once. I'd been ordering from their consciously quirky catalogue for years, so visiting the place itself felt like a pilgrimage, like visiting the Moosewood Café. Though if memory serves, I didn't love eating at the Moosewood as much as I loved my adaptations of their recipes. I did love Zingerman's, though.

I miss sitting in an airplane seat, watching the ground recede. Wandering through Zingerman's, inhaling the scents of freshly-baked bread and intense spices and little samples of cheese on toothpicks free for the tasting. Being in a busy place surrounded by other people, breathing shared air, safely. Remember that?

As I dig into the feeling, I realize it isn't only about travel, though I'm eager for the day when I can visit family in Texas again. I miss being able to go to my local coffee shop for a latte with a congregant or a friend, cupping my hands around the mug to sip the hot milk foam. I miss browsing in bookstores.

Tonight's Shabbat dinner will happen over Zoom with my congregational community. I'm grateful for that, and for every bit of digital connectivity I can muster. I still miss the casual connectivity of exploring an unfamiliar delicatessen surrounded by friendly strangers. Will I remember to treasure that, if we ever get it back?

January 30, 2021

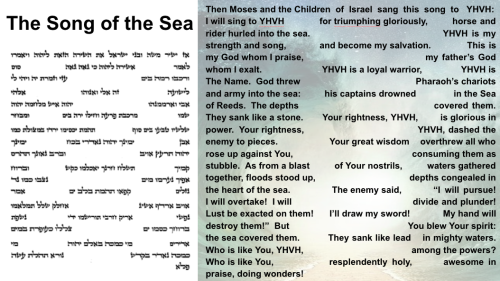

I will sing

In this week's Torah portion, Beshalach, we read the Song at the Sea. "I will sing to God..." Our commentators note that this verse is in future tense: not "I sing," but "I will sing." Hold on to that; we'll come back to it.

The rabbi of the Warsaw Ghetto, the Piazeczyner, notes that many of our psalms are called songs. They name themselves that way, in the opening phrase. The name "songs" seems to imply praise and thanksgiving, but often these psalms contain sorrow and fear. So why don't we call them laments? Why do we call them songs, even when they express something painful?

Talmud teaches us to call them songs because that name reminds us to seek the spark of good within the pain. Phrased another way: a "song" is something that's authentic. Song doesn't just mean happy-clappy, it means expressing the heart. Sometimes what we have to express is sorrow and fear, but that expression opens us to a spark of good within whatever's unfolding.

And... the Piazeczyner notes that it can be difficult, almost impossible, to truly sing while enduring suffering. "In order for a person to sing, their essential self -- heart and soul -- must burst into song." And sometimes, we just can't get there.

I underlined that phrase in my book because it speaks to me so deeply. It can be difficult, almost impossible, to truly sing when we're suffering. Some of us may be finding it difficult to sing in month eleven of the pandemic. Tired of staying home, fiercely missing other human beings, fearful of new and more contagious variants, grieving more than 433,000 dead so far.

Some of us may be finding it difficult to sing because we're lonely or worried about loved ones. Or because we're still shaken by the violent storming of the Capitol building earlier this month, or distressed by conspiracy-minded voices that blame recent years' wildfires on Jewish-funded space lasers. (I wish I were kidding about that.)

Sometimes, the Piazeczyner says, when the suffering is so great that our hearts feel crushed, we can't find even a spark of rejoicing. That's how he understands the kotzer ruach, constriction of spirit, described in our parsha a few weeks ago. We were so crushed by our suffering that we couldn't even hear that things were going to get better.

And yet this week our story takes us to the Sea of Reeds. We're leaving Egypt. We're singing the Song at the Sea. How did we get from "unable to even hear hope" to "crossing the Sea toward liberation"? For me, the answer is in singing our own real songs.

If we can really inhabit the song of our hearts -- even when it's a fearful song, or an anxious song, or a grieving song -- then we can be real with each other and with God. And it's in that being-real that we find the spark of hope that gets us through.

There's a debate about how the Song at the Sea was originally sung. Was it a call-and-response, in which Moshe sang each line and we sang it back? Or did we sing all together? Probably this debate arose because both of those were traditions, and somebody wanted to know which one was "right." But in typical fashion, our sages turned that debate into a deep teaching.

In Egypt, our sages teach, we sang praises as a call-and-response. We couldn't muster praise on our own, but we could repeat it. (So yes: call-and-response is correct.) When we crossed the Sea, we all sang together. Our own hearts sang out. (So yes: singing in unison is correct too!) Tradition even teaches that our song then-and-there arose from direct personal experience of God.

Sometimes all we can do is repeat someone else's words. We repeat the words of our prayers, we mirror someone else's hope. At other times our own song pours forth. Both of those are authentic spiritual life. And when we're willing to be real, we open to our own song. That's how -- even when still in Mitzrayim -- we became able to envision that things would someday get better.

That's why "I will sing to God..." is written in the future tense: it speaks to the future song that we know we will someday be able to sing.

Someday we'll be able to safely gather in person. Someday we'll be able to safely sing together in person. Right now we may still be in Narrow Straits, but let's be real with each other: that's how we open the door to hope. Someday songs of praise will sing forth from our hearts when we sing together, when we dance together, when it's safe to be together, on the far side of this Sea.

This is the d'varling I offered on Shabbat morning at my shul (cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

Shared with gratitude to my hevruta R. Megan Doherty for studying the Aish Kodesh with me this week.

Image source: R. David Markus.

January 29, 2021

Discipline

I only see a few people in person. Is it still correct to call us a pod when there's no formal quarantine? Whatever we're called, we are few in number. Over the summer I saw a few others -- outdoors, because fresh air felt safer -- but since the cold returned, it's been just us. I think of people I've known who chose a monastic life. What is it like to abandon a previous life with its social whirl, and to forge new spirit in the combination of enforced isolation and enforced togetherness? Is it anything like this?

Last spring the shelves of grocery stores were often bare. No toilet paper, no flour, no Clorox wipes. Fruits and vegetables were hard to find, for a while. We haven't returned to those levels of privation (yet) this winter, but there are ingredients I can't find. I think of previous generations cooking during wartime, or in the shtetl, or in the Warsaw Ghetto. (I don't want to think of subsisting on what food was available in the camps.) This isn't like that, but that's the narrative frame that comes to mind.

When I read about people who refuse to wear masks or maintain social distancing, I think: would you have turned on your lights during the Blitz? It's not a kind thought, but I struggle to feel kindness toward those whose actions put others at risk. Much about this pandemic year feels like a discipline: staying apart, staying masked, staying alone, cooking with what I can get. The hardest discipline is maintaining a healthy balance between facing reality, and not perseverating about the reality we face.

The hardest discipline is cultivating hope. This week on the Jewish calendar we mark the New Year of the Trees. Symbolically, spiritually, the sap of the coming spring and summer is beginning to rise. The potential for flower and fruit lies coiled in every seed. The days will lengthen. The vaccine will become available to everyone. The branches that are now bare will carry a profusion of fruit. Can I hold the experience of January's bitter cold alongside the certainty that in its time spring will come?

January 25, 2021

Interview at On Sophia Street

I met Rabbi Laura Duhan Kaplan when I was in rabbinical school, where she was one of my professors. These days I am honored to call her a colleague and friend. She recently visited my shul (via Zoom, of course) to share about her latest book, The Infinity Inside, a beautiful collection of essays and spiritual practices.

I met Rabbi Laura Duhan Kaplan when I was in rabbinical school, where she was one of my professors. These days I am honored to call her a colleague and friend. She recently visited my shul (via Zoom, of course) to share about her latest book, The Infinity Inside, a beautiful collection of essays and spiritual practices.

She's also a blogger, and has been sharing her words at On Sophia Street for ten years. In celebration of her tenth blogiversary, she recently interviewed me for her blog (and will be interviewing two other spiritual bloggers -- subscribe to her blog to read those interviews too!) We talked about poetry, liturgy, spiritual practice, grief work, Crossing the Sea, and more. Here's a taste of our conversation:

Laura: You’re a life-long writer and a long-time blogger. Can you tell us a little bit about why you write? Do you see it as a spiritual practice?

Rachel: Writing is my most enduring spiritual practice. I’ve been writing my way through the world for as long as I can remember. Sometimes writing is a gratitude practice, a way of articulating to myself the things in my life for which I can honestly say modah ani, “I am thankful.” Sometimes writing offers a lens onto a tangled knot of thinking and feeling. Sometimes I look back at what I wrote and that gives me perspective on what’s constant and what changes.

EM Forster is reported to have said, “How do I know what I think until I see what I say?” I love that. Writing, like prayer, is how I come to know myself...

Read the whole interview here: Rachel Barenblat: poetry, liturgy, spiritual practice.

January 24, 2021

A year out of time

Out for "frozen hot chocolate" with my dad, the year we lived in New York city.

The year I was in fifth grade was the year my parents and I lived in New York city. One of my brothers stayed in our San Antonio house while we were gone. We spent that year in a sleek modern apartment on the 37th floor of an Upper East Side apartment building, with an elevator and a doorman. Everything was different from the life I'd known in Texas.

I remember the diffuse light that filtered through our paper windowshades at night. I remember attending a city school, endlessly running up and down flights of stairs. I remember a candy shop where my father would buy me white-and-milk-chocolate mushrooms with caramel-filled stems and toffee-brickle caps.

I remember making maps, endlessly taping together my mother's typing paper and drawing grids to mimic Manhattan, marking every restaurant I had visited, every theater, my school, the hospital where my dad went into traction when he threw out his back. The literal maps bespoke a metaphorical truth: I was trying to make sense of where I was.

My child's fifth grade year is not like any other that came before. (I hope it won't be like any that comes after, either.) His school supplies live in a plastic box that he carts from place to place. His teacher and classmates are on Zoom. He gave a google slides presentation to his library class last week with headphones on at our dining table.

There's one kid in our quarantine pod. Otherwise his social life is digital, like his schooling. He plays Minecraft with two groups of friends (and with his parents.) He voice-chats with school friends on one device while gaming on another. I know how lucky we are to have the devices. It still isn't easy. Nothing about this year is easy.

When he looks back on this year, I hope he'll remember teaching me how to Minecraft, kvelling when I learned how not to be a "total n00b." I hope he'll remember fresh challah and singing Shabbat blessings, learning to ride a horse, and creating vast imaginary realms with his friends even though they are physically staying apart.

I wonder whether this year will feel to him, later, like a year out of time... the way my fifth grade year came to feel once we moved back to Texas, leaving the glamour of the big-city apartment to return to our old limestone house in the suburbs with the giant magnolia tree in the front yard and playmates across the street and one house down.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers