Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 40

January 21, 2021

First shot

My appointment was at 3pm at a church in North Adams. I've driven by it a million times but wasn't sure how to get in or which door would be open, so I arrived early. A masked volunteer from the local Community Coalition was standing outside on the steps with a clipboard and a bright blue uniform-type vest. On the back of her vest was a sign that said "Emotional support person" with a smiley-face.

"Rabbi Rachel!" she greeted me. "You can't go in until five minutes before your appointment." She sounded apologetic. I told her not to worry. I tucked my hands into my the pockets of my bright purple coat. It's 26 F here today: cold enough to see our breath if we weren't all wearing masks. I was wearing two, a KN95 with a pretty cloth one over the top, because I wasn't sure how crowded it would be.

While I waited, I greeted a phalanx of men in long black coats: one of the families that runs the local funeral home. After they went in, I heard one of the volunteers ask, "Did they get dressed up for this?" (I offered that in my experience, they're always dressed up. It's just the uniform, in the funeral business.) I thought again about how what they do, balancing logistics with pastoral care, is a form of ministry.

At 2:55 they let me in. Inside the church building someone took my temperature and sanitized my hands. I saw volunteers in bright yellow vests, and in bright blue vests, and in EMT uniforms. Everyone seemed happy. I filled out paperwork, I answered questions, I sat down at a freshly-sanitized table and rolled up one sleeve. A friendly EMT said "a little pinprick in three, two, one." I said a silent shehecheyanu.

I sat for fifteen minutes, dutifully, to make sure I didn't have a bad reaction. I imagine the arm will ache, later, like it did when I got vaccinated for typhoid and yellow fever before my first trip to Ghana. I'm startled to realize that that was more than 20 years ago. I remember that we needed to find a doctor who specialized in travel medicine. I wonder what became of the fold-out yellow card I carried in my passport then.

So now I'm halfway vaccinated against covid-19. This isn't going to change my behavior. We don't know yet whether or not the vaccines protect against asymptomatic spread. And besides, I won't begin developing immunity until two weeks after the second shot. But it feels to me like one more reason to hope. Every person who gets vaccinated brings us one step closer. Someday we'll embrace again.

January 15, 2021

Not the end of the story

In this week's Torah portion, Va'era, God hears the cries of the Israelites and promises to free us from bondage. But when Moshe comes to the children of Israel to tell them that, Torah says:

In this week's Torah portion, Va'era, God hears the cries of the Israelites and promises to free us from bondage. But when Moshe comes to the children of Israel to tell them that, Torah says:

וְלֹ֤א שָֽׁמְעוּ֙ אֶל־מֹשֶׁ֔ה מִקֹּ֣צֶר ר֔וּחַ וּמֵעֲבֹדָ֖ה קָשָֽׁה׃

They did not hear Moshe, because of kotzer ruach and hard servitude.

Rashi explains the phrase kotzer ruach by saying, "If one is in anguish his breath comes in short gasps and he cannot draw long breaths." For the Sforno, kotzer ruach means "it did not appear believable to their present state of mind, so that their heart could not assimilate such a promise."

So which one is it, a physical shortness of breath or a spiritual diminishment that keeps hope beyond our grasp? Of course, the answer is both. Body and spirit are not separable. If you've ever had a panic attack, you know the feeling of being physically unable to breathe because of an emotional or spiritual reality.

Kotzer ruach means that we were short of breath in body and soul. Our breath and our spirits were in tzuris, suffering. Literally at this point in our story we are in Mitzrayim (hear that same TzR /צר sound there?) But this isn't about geography, it's about an existential state of being so constricted that we couldn't even hear the hope that things could be better than this.

I know a lot of us are navigating heightened anxiety these days. A scant ten days ago, an armed mob refusing to accept the results of November's election broke in to the US Capitol with nylon tactical restraints and bludgeons. Many members of that mob proudly displayed neo-Nazi or white supremacist identities.

It's becoming increasingly clear that the attack on the Capitol wasn't spontaneous, but planned. The FBI is warning now about armed attacks planned in all fifty state capitols and in DC, on inauguration day if not before.

The covid-19 pandemic worsens by the day. We keep breaking records for number of sick people and number of deaths. Meanwhile the integrity of our country feels at-risk. I mean both our capacity to be one nation when some portion of that nation refuses to accept electoral defeat, and our moral and ethical uprightness.

Anybody here feeling kotzer ruach? Me too.

And... Our Torah story comes this week to remind us that kotzer ruach is not the end of the story. Being in dire straits -- unable to breathe, unable to focus, hearts and souls unable to hope -- is not the end of the story. On the contrary, it's the first step toward liberation.

In our Torah story, our kotzer ruach causes us to cry out. That's where this week's Torah portion begins: with God saying hearing our cries and promising to help us out of narrow straits. If you have a prayer practice or a meditation practice or a primal scream practice, now is the time to cry out. (And if you don't have such a practice, now is a good time to start.)

I don't actually believe that God "needs" us to cry out before God takes notice of us. I think it goes the other way. We need to cry out, because that's the first step in opening our hearts to God -- to hope -- to the possibility that things can get better.

The path toward the pandemic getting better is pretty clear. We shelter in place as best we can, we stay apart, we wear our masks, we get the vaccine. And then we probably keep wearing our masks. But in time, it will be safe to gather again outside of our household bubbles. In time, we will be able to gather in community, and sing together without risk, and embrace.

The path toward restoring the integrity of our nation is less clear to me. I think it involves accountability, and justice, and truth, because I think integrity always asks our commitment to those ideals. Regardless, we begin that journey from here, where we are, crying out with our anxious and broken hearts.

We've entered the lunar month of Shvat, known mostly for Tu BiShvat, the New Year of the Trees, which will take place at the next full moon. The full moon after that brings Purim. And the full moon after that brings Pesach, festival of our liberation. These three full moons are our stepping-stones to spring, and change, and freedom.

When I was working recently with the rabbis and poets and artists of Bayit on new liturgy for Tu BiShvat, one of my colleagues said something that moved me so much I wrote it on a post-it and stuck it to my desk. I wrote,

"Karpas dipped in tears -- like the tears that water our new growth."

Karpas is the spring green we dip in salt water during the seder. The salt water represents the tears of our enslavement, the tears of feeling stuck in kotzer ruach. For us this year those might be tears of grief at covid-19 deaths: 381,000 and counting. They might be tears of grief at how far our democracy has fallen from its ideals, or tears of fear for whatever may be coming.

Our tears can water new growth of heart and soul. Our heart's cry now is the first step toward the changes that will lead to liberation. Then we will fulfill the words of the psalmist: "Those who sow in tears will reap in joy." Kein yehi ratzon.

This is my d'varling from Shabbat services at my shul (cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

Illustration, by R. Allie Fischman, from Connections: Liturgy, Art, and Poetry for Tu BiShvat, Bayit, 2021.

January 12, 2021

Watching armed insurrection from afar

The lake has frozen.

Ice fishermen scatter,

tiny dark figures

making their way

across its flat

white expanse.

My heart pounds

gunfire

in my chest.

If the ice breaks

there is no one

to call.

I drove past a frozen lake this morning on my way to get my allergy shots. Every year I watch this lake freeze. Every year I watch the ice fishermen settle on the ice. Every year I spare a thought about the danger in what they're doing, especially when the ice is new. Right now it feels like our whole nation is on thin ice.

If you are struggling with increased anxiety these days, you are not alone. Please reach out to a trusted clergyperson, a therapist, a friend, the national suicide prevention hotline or crisis textline. And reach out to people you know even if you're okay, because the people you know might not be.

January 10, 2021

Count on

What I can

count on, when

democracy might be dying

at the hands of white men

and women waving

Confederate flags, wearing

Camp Auschwitz shirts,

brandishing zip ties:

the havdalah candle's

sizzle, plunged

into wine; the scent

of shankbones, simmering;

the song of Torah

where every sentence

culminates, with no

uncertainties;

the winter sun

lingering

just a little longer,

promising better days.

January 7, 2021

What I wrote to my community today

It is rare to know that we are living through a moment of genuine historical significance. To recognize that something unfolding around us will be chronicled in books as a turning point of some kind, though we can’t yet know where this turn will lead. But here we are. We will not soon forget the sight of an angry mob, incited by falsehoods, storming the nation’s Capitol.

When Congress re-convened last night, Senator Chuck Schumer spoke about the desecration of our temple of democracy. His use of that metaphor evoked our Chanukah story about our holy temple, first desecrated and then rededicated for sacred use. And I remembered again Chanukah’s message of light in the darkness, and the steadfast hope that can carry us through.

I know that many of us are feeling stunned, horrified, and even frightened by what just happened in Washington DC. If that’s you, know that you are not alone. Know, also, that I am holding each member of our extended community in my prayers and in my heart, and that I am here to listen if you need an ear and to pray with you if that would bring you comfort.

When the dust clears, our task will be the same as it ever was. As Representative John Lewis z”l (of blessed memory) taught, democracy is not a state, it’s an act — an action, a choice, something we do. That teaching feels very Jewish to me. After all, Torah exhorts us to care for the vulnerable, to love the stranger, and to pursue justice: all actions, all things that we do.

Democracy is an action. Love is an action. Justice is an action. Standing up for truth is an action. Building community is an action. These are our work, now as ever. This moment invites all of us to recommit ourselves to those holy tasks. And it invites us to create and strengthen our community by reaching out to each other in these uncertain and overwhelming times.

One thing we don’t have to do is stay glued to 24/7 news coverage. Please take care of yourself. I recommend sticking with trusted media sources and giving yourself permission to turn away if the news is causing harmful anxiety. What happened yesterday is horrifying… and we are safe here, and I hope and pray that our democracy will emerge from this stronger than ever.

May the coming Shabbat bring nourishment to our souls and balm to our weary hearts. May we take comfort in our connections with each other. And may we be inspired to work toward healing for our precious democracy, so that our nation may continue to grow toward the promises inherent in its founding, promises of human dignity and justice for all.

January 5, 2021

Fellow travelers

Later this month I'll begin teaching a class at the Academy for Jewish Religion (NY). It's part of their Sacred Arts program, and will interweave text study (Tanakh, liturgy, psalms, prophets, lifecycle) with creative writing. The syllabus was due to the dean a few weeks before the beginning of the spring term, and I've been assembling my text packet: essays, poems, prayers, classical midrash, sources ranging from ancient to contemporary. And that sent me on a journey of rediscovering my own bookshelves.

A year ago I installed new bookshelves in my home office. In those days, of course, I only worked in my home office a few days a week; the other days were spent in my synagogue office doing synagogue work. Over the last ten months everything has turned upside-down, and now I work from home almost all the time. I used to keep most of my rabbinic books at shul and most of my poetry books at home. ("Most," because the two categories aren't entirely separable.) But that too has shifted.

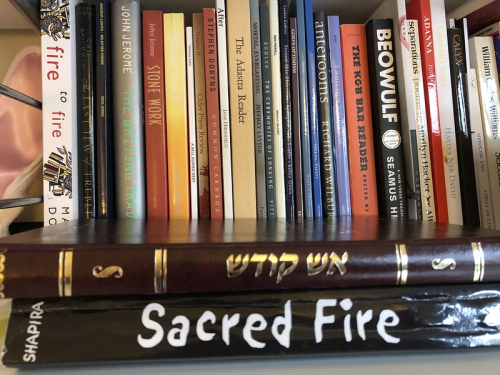

My Aish Kodesh volumes (the rabbi of the Warsaw ghetto, whose work my Bayit colleagues and I studied last year) are piled now crosswise in front of a section of bookshelf that holds Mark Doty, John Jerome, Jane Hirschfield, Yehoshua November, and Seamus Heaney's Beowulf. There's a small shelf full of Hasidut directly above Muriel Rukeyser, Jane Keyon, and The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics (now no longer "new" by a long shot -- my MFA was more than 20 years ago.)

The book I wanted to find was Diane Lockward's Eve's Red Dress. In the Torah module of my class, we'll be doing a close reading of the creation stories in Genesis and a close reading of the Akedah (the Binding of Isaac). We'll read some classical midrash arising out of both. And we'll read some contemporary poetry arising out of both. "Eve's Red Dress," I thought. "It's somewhere in this room. I think the spine is red. Is the spine red?" My books are not alphabetized. Surely I could find it.

I did find it, eventually. (The spine is not, in fact, red.) I had forgotten that my copy is inscribed; we hosted Diane for a 2003 reading at Inkberry, the literary arts nonprofit that I co-founded with two friends before I started rabbinical school. Along the way I unearthed other books that have been beloved to me: Rodger Kamenetz' The Lowercase Jew. Muriel Rukeyser's The Life of Poetry. Brenda Euland's If You Want to Write. I wished I had the space and time to get to know those old friends again.

I did pull a few things off the shelf to reread, in bits and pieces, as my scattered pandemic focus will permit. (I resonated a lot with Jess Zimmerman's essay It's Okay If You Didn't Read This Year, published in Electric Literature last week.) If nothing else, there's comfort in recognizing these spines as fellow-travelers, voices who have accompanied me over the years. I don't see anyone in person outside of my quarantine pod, but encountering the many voices in these volumes helps me feel less alone.

December 28, 2020

End of December

I glance at the headlines. The pandemic is worsening, as everyone said it would do come wintertime, and yet air travel hit a record high for the winter holidays. I can't make sense of that juxtaposition. I mean, I can; I understand that people are traveling to be with each other, even though the pandemic is worsening and Dr. Fauci says the worst is yet to come. I just don't want to believe it. I don't want to think about the suffering that is coming. I close the browser tab, but the imprint of the news lingers.

I don't go into the grocery store anymore. I place orders online, and a friendly masked employee brings paper bags of food to my parked car and places them in the hatchback. Sometimes I don't get exactly what I expected. Once I ordered some white American cheese for my son and then laughed out loud when I saw the size of the box -- 72 slices is a lot, it turns out! (He ate all of it, though. We make a lot of quesadillas, these days.) Ingredient unpredictability is strange, but I'm getting used to it.

I remember shopping at Farm to Market on the Austin Highway with my mother when I was a teenager. How she would ask the man who worked in produce to help her find a really good melon, the sweetest cantaloupe or honeydew. Something about tapping the shell and listening to its sound. Or maybe it was that he knew the subtle scent of a melon that's just right. These days I trust someone else to choose my produce for me. I tell myself that this new trend has created jobs for those who fill our bags.

This week I'm reading recipes for black eyed peas. I grew up in the South; we always ate black-eyed peas on New Year's Day, for good luck. Michael Twitty writes beautifully about that custom. I like the idea that they symbolize the eye of God, always watching over us. Black-eyed peas and greens: I learned them as a kind of kitchen magic, a symbol of prosperity, calling abundance into the coming year. We always ate tamales on New Year's Day, too. I don't have the capacity to make those.

I daydream briefly about making redred (Ghanaian black-eyed pea stew) with kelewele (fried plantains) on New Year's Day, though I'm not sure I trust the produce shopper to choose suitably overripe plantains for frying up gingery and sweet. Evidently that's the place where my mother's produce section pickiness shines through in me. Pick me a head of lettuce, sure. Choose a cucumber or a box of strawberries or a bunch of broccolini, no big deal. But when it comes to plantains, I'm dubious.

I will stay home and fill my kitchen with whatever spices' fragrance I can, this New Year's Day which will darken into the first Shabbat of 2021. It is going to be a long, solitary, quiet winter. Quiet is good: hospitals are not quiet, ventilators are not quiet. Boredom and loneliness are better than the alternative. I will curl up with a bowl of black eyed peas in my little nest on New Year's Day, and dream about how good it will be when, vaccinated, we can embrace in the gentle breeze of longed-for spring.

December 23, 2020

On the far shore

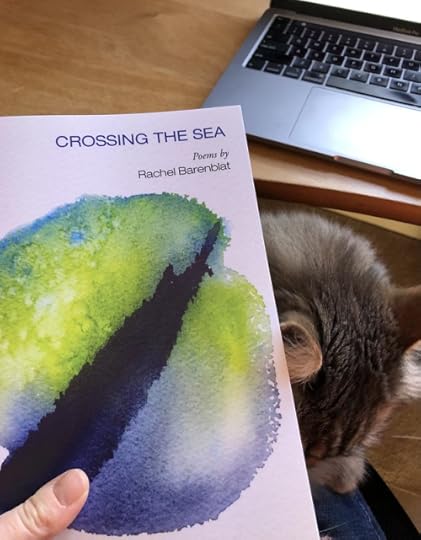

I heard that President Obama's memoir had to be printed in Germany because there is a paper shortage in the United States. The paper shortage is because we've been using so much cardboard to make so many more shipping boxes since the pandemic obligated us to stay home. I don't know if any of that is true, though it seems plausible. A parable about unintended consequences. I thought of it often in the days after Crossing the Sea launched, because I didn't yet have a copy in my hands.

Then I started getting photos from friends and family who had pre-ordered the book from Amazon or from the publisher. I was starting to wonder whether my copies were uniquely held up somewhere when the box landed on my doorstep. It's a cliché to say that my heart rate quickened as I cut the packing tape and lifted the first copies out of the wrapping, but it's also true. I'd seen the manuscript in PDF form many times, but there's something fundamentally different about a paper book.

The poems have a realness now that they exist in the tangible world. The collection is no longer the proverbial tree falling with no one to hear it. The journey it chronicles feels so far away now -- evidence that "doing the grief work" actually does work, I guess. I remember what it was like in those early days and weeks, but I remember it at a remove. Through a glass darkly. Like rereading my poems from my son's infancy. I know that was me, but I can't inhabit that space anymore.

A few of Mom's friends have written to say that they see her in this book, and a few people who are grieving now have written to say that their own journey feels mirrored here. There's no higher praise. I hope that Mom would be honored by the existence of this book. (I hope that, "wherever" she is, she approves.) And I hope other mourners will find comfort and consolation here. That's why I write. It's always why I write: not for solipsism's sake, but to shine a light for others in the darkness.

Available at Phoenicia, on Amazon, or wherever books are sold.

December 18, 2020

Seeds

I curl my fingers

into the thatch

inside the hollow.

Out come seeds

little teardrops

slippery and pale.

As they fall

the china bowl

rings like a bell.

These shortest days of the year are always a struggle for me. Like my mother before me, I count the days until the light will begin to increase. I practice finding sustenance in small things: in zesting an orange for cranberry bread, in cooking a new recipe, in turning squash seeds into a roasted snack instead of throwing them away as I would once have done. This pandemic winter, those coping mechanisms feel even more critical. There's so much I can't repair in this terrible and beautiful world. Sometimes it feels almost inappropriate to seek pleasure when there is so much suffering. In those moments I remind myself that I would honor no one by ignoring the little blessings I can find even in these times. May balm come to all who suffer, and may life's tiny sweetnesses help us through.

December 13, 2020

Windows

Once I compared daily prayer

to a chat window open with God

all the time. That was before.

Now the chat windows where I text,

the Zoom windows where we meet,

are as fervent as prayer:

the only way we can be together

anymore. The digital windows open

between my home (my heart) and yours --

they're what link us, together apart

like lovers with hands pressed

to far sides of thick glass.

Chanukah candles go in the window

to shine light into the world

to proclaim the miracle even

in dark times. We've all seen

the old photo, chanukiyah burning

small and defiant in the foreground

and on a building across the street

the swastika's hideous slash. I put

my lights each night in my window:

tiny candles visible to anyone

driving through the condo complex.

It's not brave like the rabbi in Kiel

in 1932, though more people hate us

today than I used to imagine. Still

these little lights declare

that hatred will not destroy us.

Let's be real: no one walks past

my window in the smalltown night

so I post a photo too on Facebook

scattering holy sparks

through every browser window

proclaiming the miracle

that we're still here, that

the light of our fierce hope still shines.

[Originally published in Great Miracles Happen Here: Liturgy, Poetry, and Art for Chanukah, published by Bayit: Building Jewish. Click through to read excerpts and download the whole collection.]

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers