Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 120

August 11, 2015

Six ways to heighten Elul

This weekend we'll enter into the lunar month of Elul -- the four weeks leading up to the Days of Awe. This is the time to begin the journey of introspection and reflection which can deeply enrich your experiences of the High Holidays.

This weekend we'll enter into the lunar month of Elul -- the four weeks leading up to the Days of Awe. This is the time to begin the journey of introspection and reflection which can deeply enrich your experiences of the High Holidays.

Who have you been, over the last year? What are the things you feel great about, the things you're proud of? What are the things you feel not-so-great about, the places where you missed the mark?

One tradition says that Elul is the time to work on teshuvah, repentance / repair, in relationship with God: whatever you understand that term to mean -- God far above or deep within, the Source of meaning, the Cosmos, Parent, Beloved, whatever metaphor works best for you. This is also a good time to work on repairing our relationships with ourselves: where have we disappointed ourselves, and how can we learn to offer ourselves forgiveness? What are we most grateful for, and how can we cultivate that gratitude in our lives every day?

If we spend Elul engaged in this work, then by the time Rosh Hashanah rolls around we will already be steeped in the themes of the season, and the prayers in our prayerbook may resonate in a different way... and we'll be better prepared to spend the Aseret Y'mei Teshuvah, the Ten Days of Teshuvah between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, mending our relationships with the people in our lives. First we repair our relationship with our Source; then we can repair our relationships with each other.

Here are six ways to dive deeper into Elul:

Take a few minutes every day to breathe deeply, be present in the moment, and take your emotional-spiritual temperature: how are you feeling, not physically but emotionally? What's arising in you today?

On social media check out the hashtag #blogElul, which all month long will bring you blog posts and tweets on themes of repentance and return. (This is an annual thing organized by Rabbi Phyllis Sommer, a.k.a. Ima Bima.) You can participate, too, if you're so inclined!

Read an Elul poem every day and spend a few moments letting the poem soak in and seeing what it awakens in you. (Locals: contact me about buying or borrowing a copy of See Me: Elul Poems . You can also buy the book on Amazon if you are so inclined, and if you order the paper edition, you can get the e-book for 99 cents.)

Come to Shabbat services. Dip into song and prayer with community. You may find that it opens your heart and enlivens your spirit in ways you didn't expect.

Read, pray, or sing Psalm 27 every day. This is the psalm our sages assigned to this month. Here are some different versions to try:

Reb Zalman (z"l)'s English translation

One verse of the psalm set to music, in Hebrew, by Nava Tehila

Alicia Ostriker's psalm 27

Achat Sha'alti melody by I. Katz

R' Brant Rosen's English translation

Kirtan Rabbi's Achat Sha'alti (info) and mp3

Go for a walk. Another tradition teaches that Elul is the month when God leaves the divine palace on high and wanders in the fields, waiting for us to come and walk and talk and pour out our hearts. Take time this month to walk in the fields, hike up the mountains, and silently or out loud say to God whatever you need to.

I hope that some or all of these speak to you. We're entering one of my favorite months of the year. If we open ourselves to it, it can work some powerful transformations on our hearts and on our souls.

Wishing everyone an early chodesh tov -- may your month of Elul be meaningful and sweet.

I wrote this to send to my congregational community, and then decided y'all might enjoy it too, so I'm crossposting it (with a few modifications) here.

August 5, 2015

Missing You

Shechina is riding shotgun.

Her toenails are purple.

She's tapping at her smartphone

sending texts to the KBH.

What's it like, I ask her,

being apart? Do you wake up

melancholy and grateful

all at once, and fall asleep

thinking Shabbos can't come

soon enough, is always too short

you're always saying goodbye

and your own heart aches

to know he's hurting too?

And she looks at me

eyes kind as my grandmother

and timeless as the seas

and says, you tell Me, honey.

You tell Me.

The last time I saw Reb Zalman z"l, he spoke about conversing with God while driving. He would imagine Shechina, the immanent divine Presence, in his front seat -- and would pour out to God whatever was in his heart.

While driving recently I imagined the Shechina in my front seat... and this is the poem that ensued.

KBH is an acronym for the Hebrew phrase Kadosh Baruch Hu, which can be rendered in English as "Holy One of Blessing." Holy One of Blessing is a name associated with divine transcendence -- the part of God which is high-above and far-away. (Shechina, in contrast, is the part of God which dwells here in creation.)

When we observe mitzvot with whole heart and intention -- says the mystical tradition -- we unify divine immanence and divine transcendence, for a time.

In my deepest yearnings, can I imagine what it's like for one part of God to ache for another part?

August 3, 2015

A Vidui (Before Death)

Jewish tradition contains the practice of reciting a confessional prayer daily, annually, and before death. Some years ago, while in the ALEPH Hashpa'ah (Spiritual Direction) program, I was assigned the task of writing my own. After I was blessed recently to have the opportunity of sitting with someone who was leaving this life, I was moved to revise and share the prayer I had written.

Vidui (Before Death)

Dear One, Source of All Being --

my God and God of my ancestors --

life and death are in Your hands:

hear my prayer.

I reach out to You

as I approach the contractions

which will birth my soul

into whatever comes next.

As my soul chose to enter this life

in order to learn and to love

I prepare now to leave

through an unfamiliar door.

I'm grateful for my place

in the chain of generations.

Grateful for teachers and friends

who have inspired and accompanied me.

I've made mistakes.

Lift them from my shoulders

and bless me with forgiveness.

I open my heart to You.

Help me to let go.

Help me to release regrets

so they don't encumber me

where I'm going.

All who have harmed me

in body, mind, or spirit

in this incarnation or any other --

I forgive them.

May all whom I have harmed

in body, mind, or spirit

in this incarnation or any other

forgive me in turn.

Help my loved ones to know

how deeply I have loved them

and will continue to love them

even when this body is gone.

God, parent of orphans

and defender of widows

be with my beloveds

and bring them comfort.

Into Your hand I place my soul.

You are with me; I have no fear.

As a wave returns to the ocean

I return to the Source from which I came.

שְׁמַע יִשְׂרָאֵל ה' אֱלֹהֵינוּ ה' אֶחָד

Hear, O Israel; Adonai is our God; Adonai is One.

Related:

The vidui prayer of Yom Kippur -- and of every night, 2011.

A prayer before departing this life, 2013.

When we are mindful

Judaism believes in the particularity of time, that certain times have special spiritual properties: that Shabbat has an extra degree of holiness; that Pesach (Passover) is the time of our liberation; that Shavuot is a time unusually conducive to revelation. But they have these special properties only when we are mindful. If we consciously observe Shabbat, Shabbat has this holy quality. If we don't, it is merely Friday night, merely Saturday afternoon...

That's Rabbi Alan Lew z"l in the book I reread slowly each year at this season, This Is Real And You Are Completely Unprepared: The Days of Awe as a Journey of Transformation. Every year I start rereading the book around Tisha b'Av, the day of deep brokenness which launches us in to the season of teshuvah, repentance or return. Every year I find myself drawn to some of the same passages I underlined last year or the year before -- and every year some new passages jump out at me, too.

This year the first new thing I underlined was the quote which appears at the top of this post. I've been thinking a lot lately about sacred time, and about how being aware of where we are in the rhythm of the day and week and the round of the year can help us attune ourselves to spiritual life... and also how being unaware of where we are, or ignoring where we are, can damage that attunement. It's as though lack of mindfulness were a radio scrambler which keeps us from hearing the divine broadcast.

One of the things I love most about my Jewish Renewal hevre (my dear colleague-friends) is that we are jointly committed to seeking mindfulness. To living with prayerful consciousness, as my friends and teachers Rabbi Shawn Zevit and Marcia Prager taught us during DLTI. Knowing others who care about this stuff as much as I do is restorative. It lifts a weight of loneliness off of my shoulders. My hevre inspire me to try to be the kind of person, the kind of Jew, the kind of rabbi, I want to be.

There's much in ordinary life which pulls me away from the awareness I want to maintain. Away from consciousness of Shabbat as holy time, and of its internal flow from greeting the Bride to rejoicing in the Torah to yearning for the divine Presence not to depart. Away from consciousness of the moon and the seasons, and from the process of teshuvah (repentance / return.) Ordinary life is full of obligations, frustrations, distractions, and a whole world of people who don't care about the things I love so deeply.

Sometimes it's a little bit alienating -- carrying this tradition around with me like an extra pair of glasses, an extra lens which shapes the way I see everything in my world, all the while knowing that most of the people around me don't have this lens and probably don't want it, either. Sometimes it feels like an exquisite gift -- as though I had the capacity to see a layer of beautiful magic which overlays all things, because I'm willing to open myself to this way of seeing and this way of being in the world.

Without mindfulness, Shabbat becomes plain old Friday night and Saturday. Without mindfulness, the new moon of Elul coming up at the end of next week is just a night when we'll be able to see a surprising number of stars. Without mindfulness, Yom Kippur doesn't atone -- it's just a long day, maybe one we're spending with grumbly stomachs saying strange words in a language we don't understand. I don't want it to be like that. Not for me, not for you who are reading this, not for anyone.

There's nothing wrong with plain old Friday night and Saturday. (And so on: plain old new moon, September days instead of the High Holidays...) But because I've tasted the transformation that's possible when consciousness of holy time enlivens those hours and makes them new, I want to make these holy times more than "just ordinary." I want to sip that nectar again, and to come away with my spirit renewed. Because I know that diving deep into Jewish sacred time sustains me like nothing else.

What our tradition is affirming is that when we reach the point of awareness, everything in time -- everything in the year, everything in our life -- conspires to help us. Everything becomes the instrument of our redemption.... The passage of time brings awareness, and the two together, time and consciousness, heal... This is precisely the journey we take every year during the High Holidays -- a journey of transformation and healing, a time which together with consciousness heals and transforms us.

Here's hoping. May it be so.

Elul begins in one week. Rosh Hashanah begins five weeks from Sunday.

Shabbat shalom to all who celebrate.

August 2, 2015

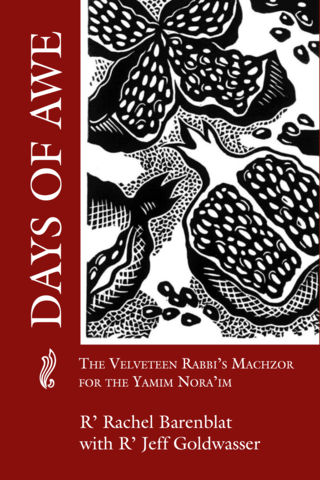

Second edition of Days of Awe

Last year I released a pilot edition of Days of Awe, a machzor (high holiday prayerbook) for the yamim nora'im (days of awe.) It was used in three communities that I know of, one of which is the community I am blessed to serve.

Last year I released a pilot edition of Days of Awe, a machzor (high holiday prayerbook) for the yamim nora'im (days of awe.) It was used in three communities that I know of, one of which is the community I am blessed to serve.

The book had a team of proofreaders, and had gone through more than 30 printed revisions before I released it, but I knew that once it was used in realtime -- "pray-tested," as it were -- I would find things which needed to be updated.

Sure enough, I found things I wanted to fix. And I discovered a few places where I wanted to add material for the second edition. In January of 2015 I began revising. A native Hebrew speaker helped me better proofread the Hebrew.

I included a new aleinu variant, and a Shaker-inspired Ahavah Rabbah. (I learned both of these from Rabbi David Ingber of Romemu.) I replaced some art which hadn't printed well with new art which reproduces better.

I added more poetry. Some is my own (like the trio of new poems for the shofar service, inspired by teachings from Rabbi Daniel Siegel and from Reb Zalman z"l), some is by other writers. I added a second option for the Torah blessings, so that people now have the option of the classical wording or a more inclusive variation. Throughout, I kept the pagination the same as the pilot edition so it can be used alongside the pilot edition if needed.

I made about 50 changes, based on my own impressions of leading davenen with this volume, my student hazzan's impressions, and the feedback I received from those who used the pilot edition last year both inside and outside my own community. The second edition is now available: bound L to R (like an English book) at Amazon, and bound R to L (like a Hebrew book) at Lulu. (And if you want it in hardcover, it's also available bound L to R -- like an English book -- in hardcover, also via Lulu.)

I'm happy to make the source files available if you want to print and bind your own copies (or use it on an e-reader)... with two stipulations: 1) Please don't sell the books anywhere at a profit, since the rabbis, artists, and poets who donated their work to this project did so on the understanding that no profit would be made from their work; and 2) If you use the machzor, either on your own or in community, please drop me a line after the holidays to tell me what worked for you and what didn't.

The creation of new liturgy is iterative. I know that this second edition is as perfect as I can make it -- and I also know that by the end of this year's high holidays, I'll discover things I want to improve. For now, I'm deep in preparations for this year's holiday services, and I'm looking forward to using this second edition as I join with our student hazzan in leading prayer. For all that is meritorious in this machzor I thank my ALEPH teachers; any remaining imperfections in this machzor are my own.

Available at Amazon $7.53 L to R (paperback) | Available at Lulu $8.46 R to L (paperback)

Available in hardcover $19.61 L to R binding

July 31, 2015

Tabernacle

The Tabernacle at the Martha's Vineyard Camp Meeting Association, built 1879.

We took a ferry to Martha's Vineyard not knowing what exactly we wanted to see. Our friends with whom we were vacationing offered to watch our kid for the day, which meant we had the option of exploring as grownups -- walking as much as our feet would bear, snapping photographs of things we found interesting, stopping to read on park benches -- the way we used to do before our son was born. Our feet led us to the Martha's Vineyard Camp Meeting Association, also known as Wesleyan Grove.

Back in the 1800s, there was a trend of summer religious camp meetings. People would come and set up temporary housing -- canvas tents, sometimes with wooden floors, sometimes with floors of earth and straw -- and several times a day, preachers would give over the gospel and the community would pray. Martha's Vineyard was home to the first religious camp meeting site in the United States. A group of Methodists set up camp here in what they described as a venerable oak grove.

As the camp became established, a few things began to shift. The central preaching area became covered by a big canvas tent, and then by a giant wrought-iron open-air worship space called the Tabernacle -- still used today.

As the camp became established, a few things began to shift. The central preaching area became covered by a big canvas tent, and then by a giant wrought-iron open-air worship space called the Tabernacle -- still used today.

Those who came to camp for the summers stayed initially in small canvas tents with wooden floors and ornately scalloped canvas rooflines. When canvas became scarce, because of the American Civil War, families began erecting small wooden cottages instead -- with similar scalloped roofs.

Some say the cottages are meant to be reminiscent of the old canvas tents. Others say their designs are meant to evoke churches. They have double front doors which open like church doors, framed by the kind of windows one often sees in churches too.

In the one cottage which is open as a museum, we saw a framed yellowing printed sheet bearing the original campground rules. Those rules indicated, among other things, that a light was to be kept burning in each tent (or house) all night, not to be allowed to go out.

I don't know why that rule was established. Maybe, as the cottage museum guide speculated, it was to prevent hanky-panky in what was then a very conservative religious campground. (We also learned that when a secular summer resort was established nearby, the religious leaders built a 7-foot wall to keep bad influences out!) But reading it, I couldn't help thinking of the repeated exhortation in Leviticus that "a perpetual fire shall be kept burning on the altar, not to go out." (See my Torah poem for parashat Tzav.)

I suspect my mind went immediately to the נר תמיד / ner tamid, the eternal light which burned in the Tabernacle (and which now burns in every synagogue) because these cottages are juxtaposed with a "Tabernacle" -- an English translation of our Hebrew משכן / mishkan, the portable tabernacle which our spiritual ancestors built so that the Presence of God could dwell within it -- or within them. (The Hebrew in Exodus 25:8 is ambiguous: "Let them build Me a sanctuary, that I might dwell within...")

Sitting in the wrought-iron Tabernacle, all I could think was: wow, it would be fun to lead a Jewish Renewal Shabbat service here with my hevre! I still remember my first Jewish Renewal Shabbat evening services, in the tent at the edge of the meadow at the old Elat Chayyim. There was a kind of tent-revival feel, and not only because we were literally davening in an open-sided white canvas tent. I'd like to daven in the Martha's Vineyard Camp Meeting Association Tabernacle someday.

July 28, 2015

Hortensias

The summer I was fifteen, I spent a month as an exchange student in a small city in Brittany. The city was called Lannion, and it was adjacent to Perros-Guirec, which was the hometown of my middle school French teacher. Each summer he took a handful of his students back to his birthplace. In retrospect, now that I have a child and live a few thousand miles away from my parents, I imagine he must have started organizing the homestays in order to help him afford to bring his kids back home.

I grew up in south-central Texas, where summers last a long time, and they're hot: really hot. (I couldn't quite fathom it when I was instructed to pack some things with long sleeves.) The beaches I knew were those at Port Aransas and South Padre Island, on the Gulf coast, where the water is warm. And the flora I knew was the stuff that grows at the intersection of subtropical and scrub desert -- very Mediterranean. I grew up with banana trees, bougainvillea, oleander, prickly pear cactus, magnolia.

Living in France was an amazing adventure. I remember dinners outside in the long light evenings -- and foods I had never before seen: langoustines, raclettes, buckwheat galettes. I remember the dolmens, erected four or five thousand years ago and weathered by rain and salt air. I remember side trips to Mont St.-Michel with its extraordinary tides, and to Rennes to visit my host family's family. I remember going to the beach. I was determined to swim in the English Channel, even if it were cold!

And I remember noticing that plants grew in Brittany which I had never before seen. I was especially struck by the lush bushes covered with giant flowers made up of many tiny blooms. I asked my host mother what they were called, and she told me hortensias. Some years later I visited the island of Nantucket for the first time with the family who would become my in-laws, and there I saw the same beautiful clusters of blossoms again, and learned their common English name, which is hydrangea.

Hydrangeas grow all over coastal New England. They grow in our backyard now, too -- though in our backyard their blooms are a simple ivory-white. In more acidic soils, like the seaside soil of Lannion (or, for that matter, the seaside soil of Nantucket and Cape Cod), the blooms are blue: ranging from periwinkle, to pale lavender, to a deep purple-blue. They're a kind of natural litmus paper. And every time I see them, I remember for an instant what it was like to be fifteen on my homestay in Lannion.

July 25, 2015

Longing, Exit 16

Turn here

if your heart aches

if someone you love

is out of reach

if a beloved

is suffering

and you wish

more than anything --

Turn here

if you've wanted

what you didn't have

or couldn't have

if love overflows

like an open faucet

if yearning is as close

as you get to whole.

On the highway recently I saw one of those standard blue signs which reads "Lodging" and then the exit number. Out of the corner of my eye I mis-read it for a moment, and thought it said "Longing, Exit 16." Then I thought: wow, I want to use that as the title for a poem.

So I did.

July 22, 2015

Almost Tisha b'Av

Tisha b'Av is coming.

On the ninth day of the lunar month of Av -- on the Gregorian / secular calendar, that date is coming up this Saturday -- Jews around the world will gather in mourning. We will mourn the fall of the first Temple, destroyed by Babylon on 9 Av in 586 B.C.E. We will mourn the fall of the second Temple, destroyed by Rome on 9 Av in 70 C.E.

We will mourn our own shortcomings, as exemplified in the Talmudic teaching that the first Temple fell because of sinat chinam, baseless hatred -- or in the Biblical story of the scouts who, sent to get a first glimpse of the Promised Land, came back on 9 Av full of their own fears and as a result doomed their generation to wander in the wilderness.

We will mourn the beginning of the first Crusade which killed thousands of Jews and which began on (or near) 9 Av; the expulsion of Jews from England and, later, from Spain, both of which happened on (or near) 9 Av; and the Grossaktion (great deportation and mass extermination) from the Warsaw Ghetto, which likewise happened on 9 Av.

Some of us, on Tisha b'Av, will also be mourning the more generalized brokenness of creation; the damage done by humankind to humankind, whether in the destruction of a holy house of worship 2000 years ago or the destruction of Black churches in America today; the horrors of war throughout the centuries, from antiquity to Hiroshima to the present day.

Some of us, on Tisha b'Av, will also be mourning the brokenness of our earth and the fear that in our lust for fossil fuel we are destroying and burning our earth as surely as the holy Temple was destroyed. Some of us will also be mourning the brokenness in our hearts and in our relationships -- our own internal walls which have crumbled, our own shattered places.

On the secular / American calendar, this is the heart of summer; a fun season, a celebratory time. On the Jewish calendar, Tisha b'Av calls us to dip into awareness of mourning. It's a little bit like the glass we break at every wedding -- a reminder that even in our times of greatest joy, somewhere in the world there still exist brokenness and sorrow.

Tradition also teaches that on the afternoon of Tisha b'Av, when we are most deeply immersed in sorrow and grief, the seeds of redemption are planted. One midrash holds that moshiach, the messiah, will be born on the afternoon of Tisha b'Av. It's like in the Greek myth of Pandora which I loved as a child: there is hope at the bottom of the box.

As Tisha b'Av approaches

We begin our descent

toward the rubble.

Our hearts crack open

and sorrow comes flooding in.

Help us to believe

that tears can transform,

that redemption is possible.

The walls will come down:

open our eyes, give us strength

not to look away.

You can find more Tisha b'Av posts in my 9Av category. I commend to you especially this pair of liturgies for the holiday assembled jointly by me and Rabbi David Markus last summer.

The above poem was originally posted in 2012, and will appear in my forthcoming collection

Open My Lips, due later this year from Ben Yehuda Press.

July 21, 2015

I Seek Your Face... in Everybody Else, Amen - a sermon for Rosh Hashanah 5776

One of my most consistent childhood memories is saying my prayers before I went to sleep. I can still remember the pattern of the wallpaper on the ceiling of my childhood bedroom, and the gentle dip of the bed from where my mom would sit next to me.

I would sing the one-line shema, and then say my litany of "God bless." I began with "God bless Mom and Dad," then named my grandparents, then named my siblings and in time their spouses and children. At the very end, I would ask God to bless "all my aunts and uncles and cousins and friends, and everybody else, Amen."

I'm not sure what I thought it meant to ask God to bless someone. But clearly being blessed by God was a good thing, and I didn't want anyone to accidentally get left out.

There's a blessing called Oseh Shalom which appears throughout our liturgy. Here are the words as you may have learned them:

עֹשֶׂה שָׁלוֹם בִּמְרוֹמָיו הוּא יַעֲשֶׂה שָּׁלוֹם עָלֵינוּ וְעַל כָּל יִשְׂרָאֵל, וְאִמְרוּ אָמֵן:

"May the One Who makes peace in the high heavens make peace for us and for all Israel, and let us say: Amen."

In many communities around the Jewish world today, including this one, another phrase is now added. That phrase is וְעַל כָּל יוֹשבֵי תֵבֱל -- "and all who dwell on Earth." Adding that phrase to Oseh Shalom is a little bit like what I did in my childhood bedtime prayers: "and everybody else, amen."

Why am I so invested in praying for "everybody else, amen"?

One of the things I admired most about Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, of blessed memory -- the teacher of my teachers in Jewish Renewal -- was his "post-triumphalism." Post-triumphalism is (maybe this is obvious) what comes after triumphalism. And triumphalism is the assumption that there's only one Truth, and it's ours.

It used to be obvious to most people that there was only one path to God, and that if we were right about it, then it stood to reason that everybody else was wrong. And someday all those people who followed the wrong religious path -- and who maybe persecuted us for choosing to follow our own instead of theirs -- would get what was coming to them! What a satisfying fantasy. Someday we'll all go to heaven and they'll go to hell, and they'll see that we were right all along. Nyah-nyah!

Reb Zalman taught that it was time to move beyond that. Triumphalism was part of an old paradigm in which truth was a zero-sum game. But as my friend and teacher Rabbi Brad Hirschfield notes in his book about moving beyond religious fundamentalism, "You don't have to be wrong for me to be right."

I don't have to declare your beloved child ugly in order to know mine as beautiful. I don't have to declare your beloved religious tradition ugly in order to know mine as beautiful, either.

Jewish tradition clearly teaches that our people is beloved of God. As the Friday night hymn "Lecha Dodi" reminds us, we are an עם סגולה, a treasured people. But surely we are not the only ones in this world whom God loves. Surely we are not the only people who have a connection to something greater than ourselves. And surely we are not the only people in the world who merit peace.

וְעַל כָּל יוֹשבֵי תֵבֱל. What can it really mean to pray for peace for everyone in the entire world? Is that too vague an idea to actually hold any meaning?

My teacher and friend Rabbi Arthur Waskow maintains a practice of adding still another phrase to Oseh Shalom. He asks God to provide peace עָלֵינוּ וְעַל כָּל יִשְׂרָאֵל, וְעַל כָּל יִשְמַעֵל, וְעַל כָּל יוֹשבֵי תֵבֱל -- to us, to all the children of Israel, to all the children of Ishmael, and to all who dwell on this earth. In using those additional words, he pushes us to pray for those with whom we are in a historical relationship which is not always easy.

This morning we again heard the story of the casting-out of Hagar and Ishmael. Both of our traditions regard the casting-out of Hagar and Ishmael as the initial rupture in the Abrahamic family. And that rupture has led to some acrimony.

This is precisely why Reb Arthur inserts that extra phrase into his prayers: because it's spiritually important to ask God to bring peace to those who have in some places and times been our enemies. What would it mean to pray specifically for those who are not like us -- to affirm in our prayers that their lives matter too?

During the Days of Awe which are now beginning, we're supposed to be doing the internal work of teshuvah (repentance, return, and repair), in our relationships. To help us in this work, our tradition gives us some beautiful tools, among them Psalm 27. For the last month, we've been singing the words

לָךְ אָמַר לִבִּי בַּקְשׁוּ פָנָי

אֶת פָּנָיִךְ, הו''יה, אֲבַקֵשׁ.

That melody comes from Nava Tehila, the Jewish Renewal community of Jerusalem. In Rabbi David Markus' singable English translation:

You Called to my heart:

Come seek My face,

Come seek My grace.

For Your love,

Source of all,

I will seek.

The Psalmist teaches us that God calls to our hearts, begging us, "Seek My Face!" And in return, our hearts call back: "we will seek You!" Seeking God's Face - seeking God's Presence, seeking a visceral awareness that this is a holy place and God is right here with me - is one of Judaism's core spiritual practices. It's an especially valuable practice at this season.

What does it mean to seek God's face? Where should we turn to seek God's face?

Imagine for a moment that the person you love most in the world is right in front of you. Imagine the way your heart leaps for joy when you see them. Imagine looking into their eyes, with all of the love that's in your heart.

That person is enlivened by a spark of divinity. That person's face is a face of God. When you look into the eyes of someone you love, you are seeing one of God's faces.

That part's easy. Here's where it gets harder: the face of someone who's difficult for you? Is also a face of God. The face of someone who is unlike you, someone who prays differently, someone who espouses politics you may abhor, someone with a different color skin...? Is also a face of God. When we commit ourselves to seeking God's Face, we have to commit ourselves to seeking that Face also in those who are not like us, just as we pray for peace also for those who are not like us.

I mentioned this morning's Torah reading, the casting-out of Hagar. On the surface of the text, this is a story about Abraham kicking out his foreign concubine. But I want to invite us to go deeper. The name Hagar comes from ha-ger, the stranger. This isn't only a story about Hagar who was a stranger. This is a story about us when we feel like strangers in our own homes, in our own hearts. Every one of us knows what it's like to feel alienated, to feel unwelcome.

Looking inward at the parts of us which have felt unwelcome, the parts of us which have felt unloved, the parts of us which have felt exiled -- that's another way of seeking God's face. We seek God's face with our willingness to face the part of ourselves which is estranged and alone.

The Jewish mystical tradition teaches that part of God's own self is exiled here in creation. When we face the part of ourselves which feels like a stranger, we open ourselves to encountering that part of God's face which is also a stranger.

And when we fragment our sense of ourselves, cutting off or seeking to ignore those parts of ourselves which make us anxious or afraid, God's presence is fragmented. We separate ourselves from God's face.

Long ago our spiritual ancestors built a mishkan, a portable dwelling-place for God's presence. As we read in Torah: וְעַשוּ ליִ מִקדַש וְשכָנְתִי בְּתוֹֹכַם "let them make Me a sanctuary, that I may dwell among them." Or maybe it says: "let them make Me a sanctuary, that I may dwell within them." In our togetherness, we create a home for God.

And when we fragment our community, God's presence too is fragmented. When we say "people who support X aren't welcome here," or "people who don't support X aren't welcome here," God's presence is fragmented. We separate ourselves from God's face.

לָךְ אָמַר לִבִּי בַּקְשׁוּ פָנָי -- "You called to my heart, come seek My Face"

We seek God's face when we open ourselves to another person's heart. Not just one heart. Not just a heart we can relate to. But everyone's heart: Jew and Gentile, friend and foe. The spiritual practice of seeking God's face demands that we seek God's face everywhere, in everyone.

In recent months, those who have come up to the bimah to recite the blessings before and after a section of Torah may have noticed that the big laminated sheet we keep on this table has changed. There are now two variations on the blessing before we read from Torah. One of them praises God Who has chosen us from among all peoples to receive Torah, and the other praises God Who has chosen us along with all peoples to receive Torah. The Hebrew varies only by a single syllable.

One version privileges the idea of chosenness; the other privileges the idea that holiness is not ours alone. Both of these are Jewish ideas. Even in antiquity it was possible for Isaiah to say, on God's behalf, "My house shall be a house of prayer for all peoples!" That's a universalistic vision. And even today it is possible to affirm that we have special obligations in the world. That's a particularistic vision.

Jewish tradition has always contained a tension between the particular and the universal. We are called to hold that tension. To see ourselves not solely as separate and unique, but also as part of a whole. Not either/or, but both/and.

The great possibility of this interconnected age is that we can build bridges across boundaries and form bonds across differences. That we can become part of something greater than "just us," without losing what makes us who we are.

In fact: we're most able to enter into relationship with others when we embrace who we most truly are. We need to know who we are, deep down -- we need to integrate even the parts of ourselves which we might be tempted to exile -- in order to be whole. And from that place of self-knowledge, we can enter safely into relationship with others, including those who are unlike us. From that place of wholeness we can seek God's face in everyone we meet.

That's what we affirm when we bless God Who gives wisdom to others as well as to us. That's what we affirm when we ask for peace not only for us but for everyone. That's what we affirm when we commit ourselves to the spiritual practice of seeking God's face in every face, and seeking God's heart in every heart.

May we never stop seeking God's face: in our own hearts, in the hearts of those whom we love, and in the hearts of those whom we struggle to love. And may that practice of seeking help us to create peace: for ourselves, and for our community, and for all who dwell with us on this precious earth.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers