Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 123

June 26, 2015

Tears and celebration

Why do we break a glass at the end of every Jewish wedding? There are many answers, but one of the interpretations which resonates for me is this: we break a glass to remind ourselves that even in our moments of greatest joy, the world contains brokenness. That's how I feel today - mourning the Charleston shooting and today's news of horrific terror attacks in Tunisia, Kuwait and France; celebrating today's news about the SCOTUS ruling on marriage equality across the USA.

This image made me cry. [Source]

Back in 2012 I wrote:

I hope that by the time [our son] is old enough to understand, the notion of a state passing a law against gay marriage will seem as misguided, plainly hurtful, and outdated as the notion of a state passing a law against someone of one race marrying someone of another. (I'm far from the first to note the painful similarities there.) I don't know who he will love; right now I'm pretty sure he loves his family and his friends and Thomas the Tank Engine, and that's as it should be. But I hope and pray that by the time he's ready to marry, if and when that day comes, he (and his generation) will have the right to marry, period. And not just in a handful of states, but anywhere in this country.

I hoped then that by the time our son was grown, our nation might have risen to the new ethical heights of granting the right to marry to all of its citizens, regardless of their gender or gender expression, and regardless of the gender or gender expression of their beloved. I never in a million years could have imagined that it would happen before he even started kindergarten. I'm grateful to everyone who devoted heart and soul to the work of making this possible now, in our days.

It's hard to wrap my head and heart around the disjunction between the sheer joy which I feel at the prospect of the right to marry being granted to every American, and the grief which arises at the news of today's terror attacks around the world. Though I think that kind of disjunction is part and parcel of ordinary life. It's a little bit like having a parent in the hospital while one's child is celebrating a joyful milestone -- love and sorrow, joy and grief, intertwined. Most of our lives contain these juxtapositions.

One of the pieces of framed art on my synagogue office wall contains a famous quote from the collection of rabbinic wisdom known as Pirkei Avot: "It is not your responsibility to finish the work of perfecting the world, but you are not free to desist from it either." Our nation is still marred by many inequalities, and there is much work yet to be done. Our world is still marred by endless brokenness. But I believe it's also important to stop and celebrate what we can, when we can. Our hearts need that.

Today we celebrate the SCOTUS ruling on marriage equality. Tonight we celebrate Shabbat, and may imagine that the Shabbat bride looks a bit more radiant than usual in reflection of this joyful news. And when the new week comes, it will be time to put our shoulders to the wheel and keep working toward the dream of a world free of hatred, free of violence, free of bigotry, where everyone on this earth truly knows and feels that we are all made in the image of God and all deserve safety and joy.

May those who are grieving lost loved ones in Tunisia, Kuwait, and France -- and for that matter Charleston SC, and everywhere else tarnished with acts of hatred -- be comforted along with all who mourn. May we gather up the shards of their broken hearts and cradle them lovingly as we celebrate today's victories for human rights. And for those who celebrate, may tonight's Shabbat be sweet.

Edited to add: ALEPH: Alliance for Jewish Renewal's official statement.

June 25, 2015

All the Words

I've been trying to figure out how to write about Magda Kapa's All the Words (Phoenicia Publishing, 2015).

I've been trying to figure out how to write about Magda Kapa's All the Words (Phoenicia Publishing, 2015).

This is not an ordinary volume of poems. These are brief aphorisms, glancing definitions, collected in groupings by month. They are periodically in conversation with ghostly categories written in greyed-out headings which almost escape the margins and fall off the page.

These lines, Magda writes, "are not my conclusions but my unfinished thoughts. They are my little flags to be followed or burned in time. They are crumbs I leave behind as I walk my way reading, thinking, and, of course, living."

Each of these verses was written on Twitter, so none is longer than 140 characters, and all were originally released into the world via that ephemeral medium.

Here are four glimpses, each taken from a different part of the book -- these are not parts of the same poem (except to the extent that the whole book could be read as one long poem) but in juxtaposing them I find them to be in conversation with each other even so.

Love: no matter what.

Mute: not not to speak, but not to be heard.

Grief: it comes in waves and leaves with parts of the rocks.

Line: unites and separates. And its two ends, they way the disappear in the distance, but still feel each other trembling.

There's something about "Love: no matter what" which feels, as I read it, like the promise I make to those most dearly beloved to me every time we part.

"Mute: not not to speak" -- the double negative startles me and then touches me somewhere deep. Because yes, the most painful silence is not mere silence, but what happens when one tries to speak and the person to whom one wants to be speaking can't hear.

"Grief: it comes in waves" -- like the sea; that much is a familiar image, unsurprising, but then she twists deftly to "and leaves with parts of the rocks." Yes: that is how grief is like the sea. Bit by bit it wears one away and transports one to someplace new.

"Line: unites and separates" -- that one makes me think of a line in a poem, of a line on the page...and also of an attenuated connection between two beloveds which may be thin, and may demarcate their separateness, but also holds them together so that when they tremble, they don't tremble alone.

You can support independent publishing by buying All the Words, or any of Phoenicia's many beautiful titles (including two of mine), at the Phoenicia website.

Shabbat shalom to all who celebrate!

Watching the river run

In the summer of 1989, I spent five weeks traveling the American West with a group called Man and His Land. The trip offered opportunities to taste a variety of different wilderness experiences: backpacking and canoeing in Yellowstone, a river-rafting trip in Utah, horseback riding and llama trekking and mountain biking in Wyoming, culminating in learning how to do some technical climbing in the Grand Tetons. We caravaned in a pair of big vans when we had to move from state to state.

In the summer of 1989, I spent five weeks traveling the American West with a group called Man and His Land. The trip offered opportunities to taste a variety of different wilderness experiences: backpacking and canoeing in Yellowstone, a river-rafting trip in Utah, horseback riding and llama trekking and mountain biking in Wyoming, culminating in learning how to do some technical climbing in the Grand Tetons. We caravaned in a pair of big vans when we had to move from state to state.

In retrospect, I cannot imagine what moved me to do this. I had never been an athletic kid. I always chose books or art or theatre over outdoor activities or sports. What on earth made me think that Man and His Land was a good idea? (Actually, I think I know part of the answer to that -- it was my friend Milly, who went with me. I think it was probably her idea. But I agreed to it all the same.) Of course, it was a great idea. Even bookish kids can fall in love with the great outdoors, and the trip was designed to be a supportive environment for kids to stretch themselves and find their wings. But it was hard.

I grew up in south Texas, and had been to New Mexico, so the vistas of the American West weren't as mindblowing to me as they were for some of the kids who came from more eastern or more urban locales. But I'd never experienced backcountry camping -- the kind of camping where you hike for miles into the wilderness, and carry everything in and out. I was not in good shape (although at least I wasn't struggling to shake a cigarette habit like some of the other teens) and I huffed and puffed my way up every mountain. MHL asked me to do things I didn't think I could do. Somehow, I did them.

1989 was smack in the middle of the era of the mix-tape. And our trip leader -- a woman named Barb, whom I idolized; she seemed to me impossibly wise, at the advanced age of twenty-eight -- made use of a mix tape in a powerful way. Before each segment of the trip, she would gather us around the campfire and play a little bit of the tape. The trip began with a Cat Stevens anthem: "On the Road to Find Out." Before our warm-up hike in the Great Sand Dunes National Park at the edge of the Sangre de Cristo mountains, she played us Carole King's "I Feel The Earth Move Under My Feet."

Before we went backpacking in Yellowstone, we heard Jimmy Cliff's "You Can Get It If You Really Want." Before our river rafting expedition, Loggins and Messina's "Watching the River Run." The songs pervaded and permeated our time in the wilderness in a way that wouldn't be possible now in the era of phones which double as mp3 players. It's probably unimaginable to today's teenagers to be away from their music; music lives on their phones, music lives in the cloud! But none of that was true the summer that I was fourteen. That mix tape was the complete soundtrack of that summer.

I don't consciously think about Man and His Land much. But the songs from that mixtape are still with me. Often I find the melodies and lyrics in my head, and only then do I realize what current emotional or spiritual situation has called them forth. Most of these are songs I haven't heard in decades, but they're inscribed deep in my memory. Probably the one which most frequently arises for me is "Watching the River Run." I'm not especially a fan of Loggins & Messina per se, but that one song still holds meaning. Maybe because I first encountered it at a time when I was doing a lot of emotional growing.

There's something about the metaphor of the running river which speaks to me. Like time, a river flows only in one direction. Like a life, a river may flow past great wonders and also at times great monotony. And when there are sharp rocks along a river bed, the best thing to do may be to let go and trust that the current will carry you safely to your destination. If you try to hold on too tightly to any place along the river's course, the fact of its current can hurt you. Sometimes you have to leave something beautiful behind, trusting that wherever the river is going, new beauty will be there too, waiting to be found.

Barb, my trip leader all those years ago, is still leading wilderness expeditions -- now in Alaska.

June 22, 2015

New poems for the Shofar service

On the eve of this year's first meeting with Randall, the student hazzan who will co-lead our high holiday services with me, I found myself humming the weekday evening liturgy...in the nusach, the melodic mode, of the Days of Awe. This is one of the ways in which my years in the ALEPH rabbinic ordination program rewired my brain! As soon as the high holidays are even a glimmer of future on the far horizon, their melodic waves lift me up.

I've been continuing to revise Days of Awe, the machzor which I released last year in pilot form. (More about that in another post.) One of my changes has been swapping out the poems which had previously appeared at the beginning of each section of the shofar service. I wrote those poems years ago, and one of my congregants suggested to me that we could use something new in that place.

I am indebted to my friend and teacher Rabbi Daniel Siegel for his writings on the three themes of the shofar service: sovereignty, remembrance, and the shofar itself. I commend to you his posts Malchuyot, Zichronot & Shofarot and especially Malchuyot, Zichronot, & Shofarot Take Two. Rereading those posts and marinating in those teachings (and also marinating in Reb Zalman z"l's teachings about the shofar and its spiritual meanings, as collected and cited in a variety of places, including the Jewish Renewal Hasidus blog) informed these poems greatly.

These poems will appear in the second edition of Days of Awe, though if they speak to you, you're welcome to use them even if you're not using the rest of the machzor.

MALCHUYOT

What does it mean

to proclaim Your sovereignty

when we don't understand kings?

Before the Big Bang, there was You.

In the old year

we allowed habits to rule us.

Help us throw off that yoke

so our best selves may serve You.

Help us surrender. The cosmos

is not under our control.

Help us fall to our knees

and find home in Your embrace.

Let Your power increase in the world.

Help us be unashamed of yearning.

Strengthen our awe and our love

so our prayers will soar.

ZICHRONOT

God, remember us—

not only our mistakes

but our good intentions

and our tender hearts.

Remember our ancestors

who for thousands of years

have asked forgiveness

with the wail of the ram's horn.

Today again we open ourselves

to the calls of the shofar

reminding us sleepers, awake!

We remember what matters most in our lives.

Help us shed old memories

which no longer serve us.

Help us instead

to always remember You.

SHOFAROT

The shofar reminds us

of the ram in the thicket.

Where are we, too, ensnared?

Can our song set us free?

The sound of the shofar

shatters our complacency.

It wails with our grief

and stutters with our inadequacy.

The shofar calls us to teshuvah.

The shofar cries out

I was whole, I was broken,

I will be whole again.

Make shofars of us, God!

Breathe through us: make of us

resonating chambers

for Your love.

June 21, 2015

Getting It... Together - Friday and Sunday options

ALEPH's Getting It... Together weekend is coming up soon. The Shabbaton (Shabbat retreat) is now sold out, but it's still possible to join us just for Friday night or just for Sunday's event:

Living the Legacy

Tracing Reb Zalman's vision, from Dharamsala to the Future

Sunday, July 5th, 10am – 1pm

Adler Theatre, 817 S. High Street, West Chester, PA

Tickets: $36-54; Students $18; Register here.

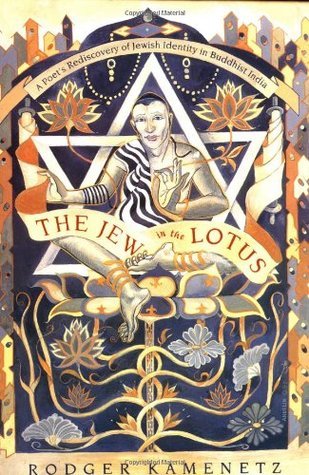

Gather for a summit of faith leaders and artists promoting the vision of Deep Ecumenism through various expressions of music, chant, dance, film & poetry. Special guest presenters include Rabbi Irving “Yitz” and Blu Greenberg, Rodger Kamenetz (author of The Jew in the Lotus, which chronicles the 1990 journey), Maggid Amitai Gross, Alaa Murad, Rabbi Leah Novick, Rabbi Moshe Waldoks, and Dr. Rachael Wooten. Featuring a 25 year retrospective of the trip to Dharamsala and moving through a vision of the future inspired by Reb Zalman's Torah and practice of Deep Ecumenism, the Sunday Celebration will be an experience of 'getting it together' not to be missed!

If you can't join us in person, you can still make a donation in Reb Zalman's memory and sign your name to the digital memory wall -- in return for which you will receive a link to watch the livestreaming of Sunday's event. Read all about it, and sign up and/or donate here: Getting It... Together.

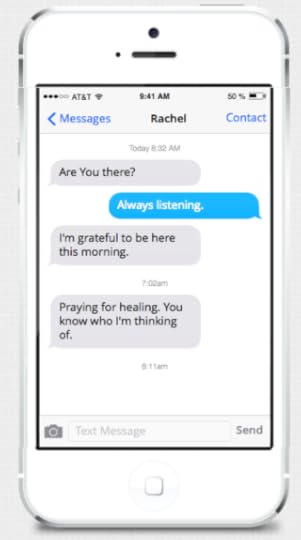

Prayer, love, and text messages

I remember, many years ago at the first retreat I ever attended with Reb Zalman z"l, hearing him talk about prayer* -- specifically about the sense one might have, at a certain point, that the words have all already been said. If one is taking on a daily (or even weekly) prayer practice, there will likely come a time when one has the feeling: I've said all of this already. Does God really need to hear this again?

But prayer isn't that kind of communication. It's like saying "I love you." Imagine that one were to say to one's beloved "I love you" -- would one's beloved respond with "eh, who cares, you said that already"? Of course not. The point of saying "I love you" is not merely conveying intellectual data. The point of saying "I love you" is creating, or rekindling, a connection on the level of the heart.

When we pray, when we engage in any kind of devotional practice, in a sense we're saying I love You to God. Ultimately it's not about the words we use or the information we're communicating. What matters is what's happening in our hearts. (And, the mystical tradition teaches, also therefore in the heart of the Holy One of Blessing. When we offer love to God, we stimulate the flow of love in return.)

If there's a way in which prayer is like saying "I love You," I think there's also a way in which saying "I love you" (lower-case "y") is like prayer.

If there's a way in which prayer is like saying "I love You," I think there's also a way in which saying "I love you" (lower-case "y") is like prayer.

Anytime I say "I love you," if I'm saying the words with intention, I'm speaking to the spark of divinity which enlivens that person -- the nitzotz elohut, the spark of godliness in that soul.

When I say "I love you" to a beloved, I'm also saying it to God. That's true whether the words emerge out of deep conversation, or whether I'm texting a shorthand ILU from my phone to theirs.

Here too the analogy between connecting with my human beloveds and my Divine Beloved holds true. Holiness is in the place of connection between I and Thou, even if that connection is brief.

There are times when I manage only snatches or snippets of regular prayer, which might as well be text messages from me to the Divine. What makes those short texts to God work is the fact that they're part of an ongoing conversation.

Any time I open my siddur, or sing lines of liturgy while driving the car, or open my heart to ask for a change I wish I could see in the world, I can feel the connection open. Every time I talk to God is "to be continued," because the conversation is never really over.

And I know that what matters is not whether I'm using "the right" words or whether I'm saying something I've never said before. What matters is that I'm saying it from the heart. When I speak from my heart, when I really mean my words, something in me opens. And if I have the feeling that you received (or You received) the words the way I meant them, then the connection between us can bloom.

*I had been absolutely convinced that I remembered Reb Zalman saying this about prayer. And then I went to look back in my retreat notes from the retreat where I was pretty sure he said it... and it turns out he said it about Torah, instead! I still offer this teaching in his honor.

June 19, 2015

Summer gratitudes

Summer twilight, Williamstown, close to 9pm.

I love breathing the air here during the summer. The fresh green scent of cut grass, whether newly-mown lawns or newly-shorn hayfields. From lilac blooms in late May to wisteria blooms in August. Right now the scent of blossoms I can't name, caught in the currents of the breeze.

I love listening to the world here during the summer. Birdsong starts early, and on a good day I get to lie in bed drifting in and out of sleep for a long time after the early dawn, listening. Behind the synagogue, redwinged blackbirds. Come evening the calls of the veery thrush spiral through the air.

I love the sky here during the summer. Some days it's a dome of infinite eggshell blue. Some days streaked with cloud. (And some days it's overcast, oh well.) At twilight there can be blue at one horizon and pink at the other; it is so beautiful that I have to stop what I'm doing and gape at the sky.

I love the tactile experiences of summer. My feet are happiest in sandals, toes free to wiggle; my arms are happiest in the sunshine and the open air. I love walking barefoot on the patches of our lawn which are shot through with curly patches of wild thyme so that every step releases spice.

I love the tastes of summer. Little local strawberries, just picked, still warm from the sun and the earth. Peaches, romaine hearts, slabs of pineapple streaked with marks from the grill and sweetened by fire. The soft-serve ice cream I enjoy with our son after a game of minigolf, licking every last drop.

It's easy for me to offer praise at this season. I see the sun disappearing behind the hills and the words of ma'ariv, the evening liturgy, flow through me. I wake to a day which has already dawned and words of gratitude are already in my heart. I'm thankful for the summer solstice, and for so much light.

June 18, 2015

More gun violence; more racism; more grief

Once again, horrific violence. A white gunman named Dylann Roof entered a Black church in Charleston, SC, and killed nine, including a pastor who was also a state senator. (New York Times: Charleston Church Shooting Leaves 9 Dead; New Yorker, Murders in Charleston by Jelani Cobb.)

According to witnesses who survived, the gunman asked for the pastor, sat next to him during Bible study, and then shot him, saying "I have to do it; you rape our women and you're taking over our country." The church in question is one of the oldest Black churches in the United States.

When I think about the racism and the hatred which underpinned this act of terrorism, I am beyond words. I react like a child: this shouldn't be possible. But it is all too possible for people to be steeped in hatred and fear of those who look different from them, and for that hatred to lead to murder.

Tomorrow is Juneteenth, the holiday commemorating the end of slavery in the United States. There is a horrible confluence in that remembrance and this latest act of hatred against Black people. And that the shooting took place in a church, a house of worship and peace, just makes it more awful still.

The victims and their loved ones are in my prayers. You can send your support and prayers with the members of Mother Emmanuel church here, and if you would like to send a donation to the church and/or the families of the victims, here's the church's website.

A a white woman witnessing this horror from afar, I feel called to teshuvah, to soul-searching. What can I do to change the reality in which this kind of hate crime is possible? I want my nation to be better than this. I want humanity to be better than this.

May the Source of Comfort bring peace to all who mourn, and comfort to all who are bereaved.

Worth reading:

"Where did this man, who killed parishioners in their church during Bible study, learn to hate black people so much?" -- Anthea Butler, in the Washington Post

"There is something particularly heartbreaking about a death happening in a place in which we seek solace and we seek peace, in a place of worship." -- President Barack Obama, remarks

"A hated people need safe spaces, but often find they are scarce. Racism aims to crowd out those sanctuaries; even children changing into church choir robes in Alabama have been blown out of this world by dynamite. That is racism’s purpose, its raison d’etre, and it has done its job well." -- Jamil Smith, in the New Republic

And here are words from one of my rabbinic colleagues: "What we need is a passionate and healing response to our national pain and fragility, one that unabashedly calls out the racist undertones of media reporting, which, it seems, differentiates by label between white, black and brown criminals and victims." -- Rabbi Menachem Creditor, in the Huffington Post

June 17, 2015

Reprint from 2004: Blog is my co-pilot

In 2004 I wrote an article for Bitch Magazine about women in what some of us were then calling the godblogosphere. It ran in their fall 2004 issue. I titled it "Women Who Blog Faithfully." They titled it "Blog is my co-pilot: the rise of religion online."

In 2004 I wrote an article for Bitch Magazine about women in what some of us were then calling the godblogosphere. It ran in their fall 2004 issue. I titled it "Women Who Blog Faithfully." They titled it "Blog is my co-pilot: the rise of religion online."

Here's my original post exhorting readers to buy the issue, which links to all of the bloggers I interviewed for the piece. Amy Wellborn is now on Twitter, and The Revealer still exists. All of the other blogs I cited are now defunct, except for this one.

Anyway, I think the article is an interesting snapshot of what at least one corner of the religious internet used to look like. (Also, wow, I used to like long paragraphs!) Enjoy.

Blog is my co-pilot: the rise of religion online

In the beginning (or “in a beginning,” or “when God was beginning,” depending on which translation you favor) God created the heavens and the earth. Some millennia later, the earth’s stewards created blogs.

In early 1999, there were about 23 webblogs; today, there are thousands, many of them eschewing the characteristic links-and-commentary format in favor of straight-up personal pontificating. The blogosphere has turned out to be a great place to discuss the kinds of things we’re discouraged from airing in polite company: among them, politics, sex, scurrilous gossip, and religion. It’s this last subject that had always interested me—after all, God tops the list of polarizing topics one isn’t supposed to bring up at the dinner table. But since I’m the kind of person who itches for a good theology throwdown, godbloggers are, well, my people.

The godblog phenomenon started early, in weblog chronology. Relapsed Catholic, founded in 2000, was one of the first godblogs, along with Holy Weblog! 2001 brought Amy Welborn’s Open Book (named after the “open Book that roots me.”) and Naomi Chana’s Baraita (the name means “external teaching” in the context of Jewish law). Chana, a professor of religion, says the name appealed to her “as an analogy for what people generally do in weblogs: provide not-especially-authoritative opinions on subjects ranging from the crucial to the trivial.” And her blog posts are true to her word: some crucial (“Have I ever mentioned why I prefer the term ‘tzedakah’ to ‘charity’ or ‘philanthropy’? It's not just the Dickensian dystopias and class warfares evoked by the latter two; it's because I know my etymology and I am trying to focus on doing something for reasons of justice, not love”), some trivial (“Is it really true that there are no kosher-for-Pesach capers? The chicken will be fine without them, but in a world with Passover cereals and egg noodles, I find it difficult to believe that nobody has plunked rabbinically examined caper buds into kosher-for-Pesach vinegar and marketed it at extortionate prices.”)

In my years of trolling the online havens of religious web philosophers, I’ve found that the most interesting godbloggers are women. Maybe that’s no surprise; a recent Pew study shows that most online spiritual seekers are women. (I suspect women make up a majority of offline spiritual seekers, too; we’re just easier to track online.) Social constructivists might link the friendliness with the gender breakdown. Old-school online culture, like Usenet, was heavy on the Y chromosomes, but not so the godblogosphere. Initially, Kathy recalls, the godblog world was all-female, though she notes “a lot of men piled on after that: the mix is now about 50/50.” Most religious spheres have historically been male-dominated; there’s still something slightly remarkable about a female minister or rabbi, and we may never see female imams or Catholic priests. But women have been godblogging from the start, so we’re not relegated to the sidelines.

There may be a good reason why women speak up on the subject of religion online—as with any online pursuit, the safety of keyboard and screen embolden people to enter public discussions that might seem daunting in real life. Furthermore, the anonymity offered by blogs let women marginalized in many offline religious spaces—synogogues, prayer groups, etc.—to blog historically patriarchal traditions from our point of view.

“Some male readers don't quite know what to make of me,” observes Relapsed Catholic’s Kathy. “They find me too hard to pin down, an admixture of orthodoxy and irreverence that shakes up their limited knowledge of women, especially [fortysomething] women like me." On the other hand, Alicia, of Fructus Ventris (“Fruit of the womb,”) mostly writes about Catholicism and birth/parenting/midwifery, and assumes most of her readers are female as a result. But, she adds, “I also have a lot of men who are regular readers and commenters.”

For some female bloggers, self-expression blurs into teaching others—though the pedagogy can be inadvertent. Karen, the blogger behind The Heretic’s Corner, is a seminarian at the Church Divinity School of the Pacific who calls herself “a mess of walking contradictions.” She figures that her very existence is educational for some: “I'm a middle-aged lesbian feminist who’s studying to become a priest. Publically putting that information out there has confounded many people. I hear from queers and straight feminists who wonder why I'm bothering with an institution that is perceived as homophobic and patriarchal. I also hear from conservative Christian men who are as shocked as hell that they can connect with me on a spiritual basis. I didn't aim at any of these people, and in fact, they educate me all the time. It's a great mutual teach-in.”

The give-and-take (or quite often, the dish-it-out-and-take-it) nature of blogs offers new chances for connection with strangers and with our own ideas of religion, but occasionally we find ourselves marginalized within them, rehashing old modes of communication—only now with more links. I used to post on several Judaism-focused message boards, but I jumped ship when arguments got nasty. So I started my one-year-old blog, Velveteen Rabbi, in order to chronicle my messy lived experience of being an intermarried and increasingly involved Jew. In my blog, I can set the tone, nurture conversations, and geek out about contemplative practice and Torah interpretation to my heart’s content.

Since starting the blog, I’ve come to feel that the online realm of godblogs feels surprisingly like my sweet little New England town—if random conversations in my town included discussing Leviticus with a minister and a Quaker half-Jew, or trading prayer techniques across denominational lines. The first time I got hate mail at Velveteen Rabbi (in response to a post supporting the rights of gays and lesbians to marry), I was furious—as though someone had come to my tea party and thrown a drink in my face. Some days, the blog feels like a pulpit with an unresponsive audience; other days it’s more like a theology pow-wow at a collegiate dining hall table, where somebody’s always pulling up another chair to join the conversation.

The goal of blogs is to relate in what philosopher Martin Buber would call an I-Thou mode, rather than relegating the other to object status. Interactivity is what differentiates blogs from newspaper columns: readers can talk back with a click of the mouse. And while that sometimes facilitates flame wars, it also enables interesting friendships. Most godbloggers report having befriended others in the religious blogosphere—and those ties inevitably stretch beyond faith and geographical boundaries. Still, there’s such a general self-consciousness in the larger blogosphere, though, that it’s worth asking whether our forums are connecting us in a meaningful way, or whether we’re simply shouting past each other about our various spiritual worlds. Most likely, it’s both. Relapsed Catholic’s Kathy writes, “I am old and cranky and find it impossible to read ‘pro-choice Catholic’ blogs or those of Chomskyite Moore-lovers without ruining my day. Life is too short.” For me—someone who believes that the real religious divisions aren’t between faiths, but between liberals and literalists—there are simply some times when I avoid conversations with bloggers from “the other side.”

On good days, though, I try to read widely. In the right frame of mind, I can get a charge out of the varieties of religious experience. And sometimes I’m pleasantly surprised by genuine human connections that form: Kesher Talk leans to the right, but they seem happy to have me there as a token lefty voice. (The blog, says managing editor Judith Weiss, “is stronger and more interesting with more diverse views.”)

Another example: an ultra-Orthodox guy emailed me a while back to chat about High Holiday melodies. On the street, we never would have exchanged a glance.We’d never have met in synagogue, either—since he wouldn’t come to mine, and at his I’d be consigned to the women’s side of the curtain. But Velveteen Rabbi got us talking.

The bonds that forms across orthodoxies and faiths may simply testify to a basic dissatisfaction with the level of public discourse about religion. Given mainstream reportage in America today, it’s easy to conflate “religious” with “fundamentalist.” The Passion of the Christ, the Federal Marriage Amendment, usage of “under God” in the Pledge of Allegiance, and the question of whether or not John Kerry deserves Communion all got major ink this year, but mainstream media didn’t do a very thorough job of addressing the broader religious questions at the root of these topics. Where mainstream media coverage often reduces discussions of religious to wild-eyed fundies vs. atheist culturalists, godbloggers live to show gradations instead of stark dichotomies. Most of the godbloggers I read don’t fit the mainstream mold: We cherish our sacred texts, but roll our eyes at posting the Ten Commandments in schools. We blog our all-night Easter and Shavuot and Laylat ul-Qadr vigils, but scoff at the televised National Day of Prayer.

As if to prove the internet axiom that individual mileage varies, though, Alicia points out that plenty of blogs are spiritually (and politically) conservative and “support authority that the bloggers see as legitimate.” She argues it’s “impossible to generalize about blogs and bloggers, because the blog is a reflection (or occasionally a refraction!) of the blogger.” Regardless of what divides us, what unites godbloggers is our need to connect with other God-types. Let’s face it: mentioning church is a buzzkill in most situations, and the play-by-play of my latest retreat bores non-initiates. Godblogs offer a place to hold forth.

But do they matter? At The Revealer last April, an unnamed blogger wrote, “Religion blogs are ornery, plagued by bad puns, narcissistic, and most of all, not real. Ok, they're ‘real,’ but they're not flesh and bone[.]” I think that’s a cheap shot at the blogosphere, and I don’t buy it. True, pixels are no substitute for genuine spiritual encounters, but my religion places a high premium on dialogue and on text.

Godbloggers are not only real, but are doing something that’s important to many in a time when religion seems more than ever like a scapegoat rather than a source of strength: We are contemplating our faith and our place in the world, caring enough to speak up about what we think matters, and, when we’re lucky, genuinely connecting with other human beings. ”I’m asking people,” Karen says, “to reflect on issues of justice, peace, and the goodness of creation.” What’s more real than that?

June 13, 2015

Revisiting Jew in the Lotus after 20+ years

25 years is a long time. Some of the things I loved 25 years ago -- the books, the ideas, the certainties -- don't necessarily speak to me now. Then again, some of the things which were formative for me two-plus decades ago are every bit as central in my life now as they were then -- maybe more so. Rodger Kamenetz's book The Jew in the Lotus is in that latter category. It was my doorway to Jewish Renewal. It's how I first "met" Reb Zalman, and Reb Zalman is the reason I became a rabbi.

I read the book when it was new, in March of 1994, when my dear friend David handed it to me saying "You really have to read this." (He was right.) This book was the door which led me to Jewish Renewal and ultimately to both my adult spiritual life and my rabbinate. (I wrote about that a while back: How I Found Jewish Renewal, And Why I Stayed.) I've dipped into the book countless times in the last twenty-plus years. But it's a long time since I've sat down to read the whole thing, cover to cover.

In a few weeks I will spend a weekend in West Chester, PA, at ALEPH's Getting It...Together, a Shabbaton (Shabbat retreat) and Sunday event which will celebrate the historic journey taken by those diverse rabbis to Dharamsala to meet with His Holiness the Dalai Lama 25 years ago. (If you're free the weekend of July 4, join us -- you can register for the full weekend, for Friday night only, or for Sunday only, and the retreat schedule and registration information are on ALEPH's website.)

What better time to reread the book which set me on my life's spiritual journey?

Part of what's remarkable for me, rereading the book now, is how some of the things which seemed radical and almost unimaginable to me 20 years ago are simply parts of my life now -- not taken for granted, exactly, but no longer surprising. "Reb Zalman...told me he saw himself as 'doing Jewish renewal, not Jewish restoration,'" Rodger writes. I suspect that reading those words was the first time I ever encountered the phrase "Jewish renewal."

Part of what's remarkable for me, rereading the book now, is how some of the things which seemed radical and almost unimaginable to me 20 years ago are simply parts of my life now -- not taken for granted, exactly, but no longer surprising. "Reb Zalman...told me he saw himself as 'doing Jewish renewal, not Jewish restoration,'" Rodger writes. I suspect that reading those words was the first time I ever encountered the phrase "Jewish renewal."

"Reb Zalman, the Matisse of religion, rearranged Jewish thought with decorative freedom...At sixty-seven, he was our loosest, freest spirit -- heir to the joy and zest of the legendary Hasidic masters." That's Rodger's prelude to the story I love so much, about how one evening-time Reb Zalman asked their driver to pull over so that he could daven ma'ariv (pray the Jewish evening service) alongside Sikhs saying their evening prayers. When I first read that story, I marveled at his openness. When I read it now, my heart beams with knowing fondness alongside the admiration.

One of the things which moves me most now, rereading this book after so many years, is recognizing that this book sparked in me yearnings for a kind of prayer I had never experienced... which is now a regular part of my life, especially any time I am together with my Jewish Renewal hevre (friends.)

Each morning before breakfast, the Jewish group assembled outside Kashmir College for shakharit davening -- morning prayers. The men strapped leather tefillin on the left arm and just above the third eye. In our brightly colored tallises and our headgear, which ranged from knit kippahs to sateen yarmulkes to Blu Greenberg's gray silk scarf to my own neo-Hasidic Indiana Jones fedora, we were quite a sight to the Tibetan kitchen workers, who always managed to break away for a glimpse. The davening was delightful: vigorous, lusty, witty and raucous, quiet and joyful.

This was all new to me.

I remember when this was all new to me, too. I remember when I couldn't quite imagine the kind of davening Rodger describes. I remember what it felt like the first week I experienced this kind of davening, and how my heart opened like a flower coming into full bloom. And I remember how it felt, when I did DLTI (the Davenen Leadership Training Institute), to discover that I too could participate in co-creating this kind of enlivening prayer. Holy wow, what an amazing journey this has been.

When I think of the passages from this book which have stayed with me, indelibly, over the two-plus decades since I first read its pages, one chapter in particular stands out: chapter 7, "The Angel of Tibet and the Angel of the Jews." This is the chapter in which Reb Zalman z"l came most to life for me, years before I ever met him in person (or even met any of his students -- many of whom I am now blessed to call my teachers, colleagues, and friends.) Of Reb Zalman, Rodger writes:

When I met him, I finally understood the whole tradition of oral masters, who are best appreciated in person, and who inspire others through their incredible flow of ideas, images, and illuminating tales. Though he holds a degree in the psychology of religion, has taught at major universities, and published both popular and scholarly works, he is much more in the line of a classic teacher of wisdom or a holy man. He is charismatic and spontaneous, with a highly developed theatrical sense, and a touch of the clown. But he is far too open about his own spiritual struggles and failings to be a cult leader. This same openness has made him attractive to many otherwise disaffected Jews -- by now a worldwide network of political activists, social workers, Buddhists meditators, writers, teachers, and rabbis who consider Zalman their rebbe.

Is it any wonder that I came away from this book thinking, "can this guy possibly be as cool as Rodger makes him sound?" It turns out, of course, that Reb Zalman was every bit as remarkable as this book depicted him to be -- and that his students have transmitted his Torah along with their own phenomenal contributions. But I don't think I could have imagined, when I first read these words, that I would someday be privileged to be one of the students of his students, ordained in his lineage.

Here's a snippet of Rodger's transcription of Reb Zalman's teaching. Reb Zalman is speaking here about the spiritual journey of Jewish prayer:

So the first part of prayer gets into the body and says to God, "Thank you for the body," and prepares the body. The second part of prayer takes you to the heart and it says, "I want to attune myself to gratefulness to God," to say, "Oh, this is a good world, oh, this is wonderful, the sun is rising. I want to give thanks." Up here in the realm of air you go to thinking, to wisdom, to trying to understand and to know. Then, going up to the highest place -- the fire -- there it isn't knowledge with the head, it is intuition.

I know that this chapter of this book was my first encounter with the four-worlds paradigm, the kabbalistic teaching which maps the four letters of the holiest Name to the four worlds of action, emotion, thought, and essence. Four worlds Judaism has become second nature to me. I use it as a frame of reference for everything I experience, not just the prayer service (though certainly that too.) Twenty years ago this was radical and new. Today it's a foundational part of my worldview.

And then, of course, there are the angels.

Reb Zalman z"l and His Holiness the Dalai Lama, in Dharamsala, 25 years ago.

"When we speak of angels," Zalman explained, "we mean by that beings of such large consciousness" -- he pointed to his forehead -- "that if an angel's consciousness were to flow into my head right now, it would be too much for me." He raised his eyebrows, and his streimel started to slide off his head. It was right out of Charlie Chaplin. An expansive angel was flipping Zalman's lid.

The rabbi straightened his streimel and continued, "There are all kinds of angels. So that higher and higher for instance, we think each nation has an angel. Right now there's an angel of Tibet and an angel of Jews that are also talking on another level. So I believe if we do it right, the Angel of Jews will put words in my mouth and the Angel of Tibet will hear them in you -- and vice versa. The dialogue is not only on this plane."

And with those words, it no longer was.

I remember this scene as though I had read it just yesterday. I remember, also, the complicated reactions from the other rabbis in the delegation. Rabbi Yitz Greenberg, who is Orthodox, noted that this is mystical tradition and that the more rationalist elements of Judaism would not affirm these beliefs. Rabbi Joy Levitt, who comes from the Reconstructionist movement, noted that some of the other rabbis in the room were hearing this material for the first time just as His Holiness was!

I was drawn to mysticism from the very first religion class I took as an undergraduate. (It was a course called "The Mysticism of the Self," taught by Thandeka. After that one class I resolved to major in religion.) But I suspect that this book, and specifically Reb Zalman's seamless integration of kabbalistic and Hasidic mystical ideas into a contemporary worldview, played a big part in shaping who I've become.

I still love the scene where Reb Zalman teaches His Holiness about gilgul, "being on the wheel," also known as "transmigration of souls" -- or what you might call reincarnation. (Are you surprised to hear that Judaism has a concept of reincarnation? When I first read this book, I know I was. And, I spoke about that in my Kol Nidre sermon from a few years ago, What Are We Here For?) I love also many moments with other rabbis on the journey. For instance, here's Rabbi Yitz Greenberg:

The Dalai Lama interrupted Yitz's history lesson to ask the inevitable question about the covenant, "The concept of the chosen people, is it right there from the beginning, or later developed?"

Rabbi Greenberg answered that it was relatively early -- and begins with the first Jew, Abraham. "Chosenness means a unique relationship of love. But God can choose others as well and give a unique calling to each group. Each has to understand its own destiny and can see its own tragedy not simply as a setback but as an opportunity."

The question of what "chosenness" means, and whether we are the only people who have a unique status of being "chosen" by God, is one with which many Jews struggle to this day. I'm humbled, now, to be reminded of these words from R' Yitz Greenberg. I know that he is one of the founders of Clal and that he has been a pioneer in ecumenical dialogue. But the fact that such a devout Orthodox Jew can assert that "chosenness" is not our gift alone moves me deeply. Rodger sees common ground:

[T]he Talmudic project as a whole represents a radical change in Judaism. As much as Yitz, as an Orthodox thinker might want to emphasize Jewish continuity, I saw in his parable of Yavneh an important lesson in Jewish discontinuity -- and Jewish renewal. I noted Yitz's words to the Dalai Lama, the rabbinic sages had to find the "courage to renew." This linked Y to Z, Yitz to Zalman, traditional to renewal, in my mental alphabet.

Rodger's naming something substantial here. This too was one of the pillars of Reb Zalman's thought: that Judaism has always grown and changed via paradigm shift. The destruction of the Temple was a paradigm shift, and out of that trauma came the birth of rabbinic Judaism as we know it. The Shoah was a paradigm shift; seeing Earth from space was a paradigm shift. (In the words of my teacher and friend Reb Victor, "Shift happens.") What new Judaisms might we now be participating in birthing?

I felt [Zalman] was representing a Judaism that once was, and that yet might be. For that reason, I didn't care that he interpreted the tradition as flowing into his own experience, his imagination, his dreams, his everyday life. He was agenting for change, for Jewish renewal. To me, renewal seemed exactly what was called for today in all traditions. What good was the rich storehouse of the esoteric in Judaism if it was only available in freeze-dried scholarly packages?

There's something amazing about rereading those words now, after following this book to Elat Chayyim, after experiencing Jewish Renewal and everything it has opened up in me, heart and soul. After five years of rabbinic school and now my own Jewish Renewal rabbinate. Of course I agree with Rodger that renewal is what's called for, across the board. It is humbling and awe-inspiring to have the opportunity to serve the ALEPH / Jewish Renewal community which seeks to make renewal real.

The story which Reb Zalman tells about the Lubavitcher rebbe teaching that his master was for him "the geologist of the soul" moves me deeply. "If you want to get to the gold, which is the awe before God, and the silver, which is the love, and the diamonds, which are the faith, then you have to find the geologist of the soul who tells you where to dig...but the digging you have to do yourself." That is a story I've heard more than once, but I know that this is where I first encountered it.

I also find myself (not surprisingly) incredibly moved by the scene where Rabbi Joy Levitt and Thubten Chodron (born and reared Jewish) are comparing life stories, talking about how each of them found her way to a spiritual path. And when Chodron says "It is so incredible for me to see female rabbis," I am reminded of how incredibly blessed I am to have been born into a moment in time when no one challenged my yearning to serve God and the Jewish people because of my uterus.

One of the meta-stories of The Jew in the Lotus is how coming to know a new spiritual tradition can enliven one's awareness of one's own as well. "Melchizedek and the Dalai Lama, shalom and tashe delek," Rodger writes. "Having opened myself to the beauty of the Buddhist spiritual tradition, I was reawakening to my own as well." I know a lot of Jews for whom that trajectory is true. My variation is: reading a book about rabbis and Buddhism awakened my yearning to move deeply into being a Jew.

"I personally appreciate any religion that honors poetry," Rodger writes when visiting the shrine of Sufi mystic and poet Hazrat Inayat Khan. (Reb Zalman was ordained in his Sufi lineage.) I couldn't agree more. (Sspeaking of honoring poetry -- I've written here over the years about two of Rodger's books of poems: here's my review of the lower-case jew and here's my review of To Die Next To You, which pairs Rodger's poems with drawings by Michael Hafftka. Both books are worth your time.)

During that visit, Rodger describes the experience of joining hands with Reb Zalman and with another trip participant named Nathan in chanting a familiar Hebrew prayer in the form of a Sufi zhikr, a devotional chant:

We repeated it in the style of Sufi dhikr and, following Zalman, tossed our heads in the four directions of time: left -- the past; right -- the present; down -- the future; and for eternity -- lifted high. The three of us became an elaborate human prayer machine -- an organic vehicle, a chariot, chanting until our necks were loose and our spirits light. It was about joy finally, the practice behind Zalman's theory of four worlds, uniting the motions of the body, the words of the mouth, and the meditations of the heart.

I am grateful to be able to say that I've had experiences like that. With my Jewish Renewal hevre I've davened Hebrew zhikr in exactly this way, and I've experienced the kind of joy and wonder which Rodger describes. Twenty years ago, this sounded to me like fantasy. Today I know that it can be real and true.

The book's penultimate chapter begins with the 1991 Kallah (the usually-biennial gathering of Jewish Renewal community -- this year the desire to hold Getting It...Together at the 25th anniversary of the Dharamsala trip displaced the Kallah, so the next Kallah will be in Colorado in 2016. Save the date!)

[At the Kallah] I saw what happens when the energy of women, of Jewish meditation, and an active four worlds approach to davening are combined. Dynamic prayer services were led by women rabbis, spiritual leaders, and singers, including among them Hannah Tiferet Siegel, Rabbi Marcia Prager, and Shefa Gold.

I wonder what I thought when I first read those words in 1994? Reading them now, all I can feel is joy. Rabbi Marcia Prager was dean of my rabbinic program. Rabbi Hanna Tiferet was an integral part of my hashpa'ah (Jewish spiritual direction) training, and I use her melodies almost every time I lead prayer. The same can be said of Rabbi Shefa Gold's melodies, which are integral to my prayer practice. These are indeed luminaries of our generation... and they have been my teachers. How great is that?

Here's one last long passage from Rodger's book, from the final chapter:

I came away with a deeper picture of Judaism and a message of Jewish renewal. As Rabbi Joy Levitt said, there's plenty of wisdom in the Jewish tradition, but what we need is a way to teach it. Doors need to be opened for the many Jews who do not have access to the richness of Jewish spiritual wisdom...

Jewish renewal will recognize the power of what is holy in our lives today... will be pluralistic, open to dialogue with other Jews and with other religions...will be more porous -- more willing to acknowledge that Judaism has borrowed from other cultures in the past, and more willing to borrow techniques and practices from other religions today, assimilating them into a Jewish context...

Jewish renewal will be more aware of its own mystical tradition... Deepening the prayer experience is essential to Jewish renewal... in effect, I'm calling for a kind of neo-Hasidism, because without an infusion of Jewish spiritual fervor in prayer and blessings and observances, the reason to stay Jewish, the juice, will be lost.

I remember reading these words as a college student and thinking: yeah, sure, this sounds amazing, but what would it really look like? Are people really doing it? (And if they are: then what would it take -- what would I have to do -- is it even imaginable for me to be able to become one of those people?) Reading them now is an entirely different experience. Yes, this is the promise of Jewish renewal, and I am blessed to know, and love, and learn with, people who are dedicating their lives to this holy work.

What comes next? I'm not sure anyone knows. But I am endlessly grateful to have the opportunity to work with, and to serve, some amazing people as we try to figure out how to continue to midwife this dream of a Judaism renewed... and I'm still grateful to Rodger for writing this book in the first place. Perhaps it was hashgacha pratit, divine providence, which led this book to David's hands and thence to mine. My life wouldn't have been the same without it.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers