Matthew Kerns's Blog: The Dime Library, page 19

December 18, 2022

Second Show

Though no night after the first would prove to be quite so disjointed and far removed from the script Ned Buntline had jotted down in his Chicago hotel room, The Scouts of the Prairie was a different show at almost every performance.

After the false start of the initial performance when Cody and Omohundro walked onto the stage and forgot their lines, theater-owner Jim Nixon attempted to avoid a repeat by offering the pair several pointers on how to appear more natural on stage. He advised Texas Jack to greet Buffalo Bill onstage when they made their entrance, “just as though you had not seen him in several years.”

So that night, as the two men walked onto the stage for the sophomore show, Jack yelled out, “Jesus Christ! How the hell are you, Bill?”

As the audience erupted in laughter, Cody responded in kind, asking, “Jack, ya damned fool! Don’t you know you are before an audience?” Texas Jack then told the audience about a winter elk hunt in the mountains of the Wyoming Territory, and the show proceeded from there.

They weren't professionals. They weren't even actors. But the audience hadn't come to see professional actors, they had come to see real heroes, and it was Texas Jack and Buffalo Bill's real lives, rather than their stage exploits, that made them legends.

December 15, 2022

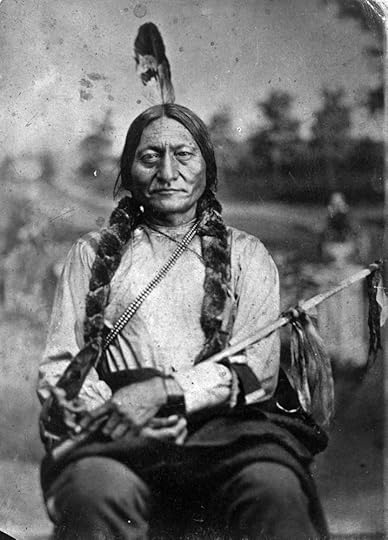

Buffalo Who Sits Down

Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake, known as Sitting Bull, was a Hunkpapa Lakota Sioux (Húŋkpapȟa / Očhéthi Šakówiŋ) holy man and leader who played a significant role in the resistance of Native American tribes to the westward expansion of the United States. He was born in the Grand River Valley of present-day South Dakota around 1831.

https://video.wixstatic.com/video/104311_7518627962c9494391976f79bc3afe8a/360p/mp4/file.mp4Sitting Bull was a leader of the Sioux tribe, who were deeply connected to the land and relied on buffalo hunting for their livelihood. As the American government began to take over their land and restrict their access to hunting grounds, Sitting Bull and other chiefs resisted.

One of the most famous incidents in Sitting Bull's life was the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876, where a coalition of Native American tribes led by Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse defeated the U.S. Army's 7th Cavalry, led by George Custer. This battle, also known as Custer's Last Stand, was a major victory for the Native American tribes, but it also marked the beginning of the end for their way of life.

After the Battle of Little Bighorn, the U.S. government increased its efforts to subdue the Sioux and other tribes, and Sitting Bull and his people were forced to flee to Canada. They eventually returned to the United States and settled on the Standing Rock reservation in North Dakota.

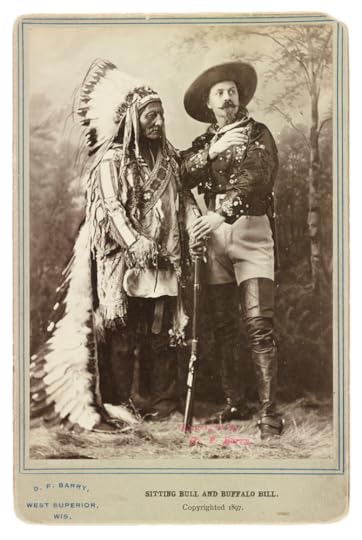

In 1885, Sitting Bull went "Wild Westing," joining Buffalo Bill Cody's Wild West and befriending Annie Oakley, calling her "Little Sure Shot." Sitting Bull was paid well to ride around the arena once per show, and made a small fortune selling pictures of himself as well as autographs, but he tended to give most of the money he earned to homeless people and beggers he met on his travels.

Sitting Bull continued to resist the government's attempts to assimilate Native Americans into mainstream American culture, and he became a symbol of Native American resistance. In 1890, he led the Ghost Dance movement, a religious movement that promised to restore the land and way of life of the Native American tribes. The movement alarmed the government, and a group of Indian police was sent to arrest Sitting Bull. During the confrontation, Sitting Bull was shot and killed on December 15, 1890.

Sitting Bull had been gifted a horse named Rico from the Wild West show by Buffalo Bill, and when the gunfire erupted the horse reared his head and began to dance, as it had been trained to do. He bowed, then stood up and pawed the ground, reared up, and leaped into the air. He cantered around and around in a circle. He did all of this while shots erupted around him that would claim the life of 16 men and two horses, but Rico was never touched by a bullet.

Sitting Bull's death marked the end of an era for Native American resistance to the U.S. government's westward expansion. His legacy, however, lives on. He is remembered as a fearless warrior and a champion of Native American rights. His memory continues to inspire Native American activism and the fight for Native American sovereignty.

December 12, 2022

Texas in South Africa

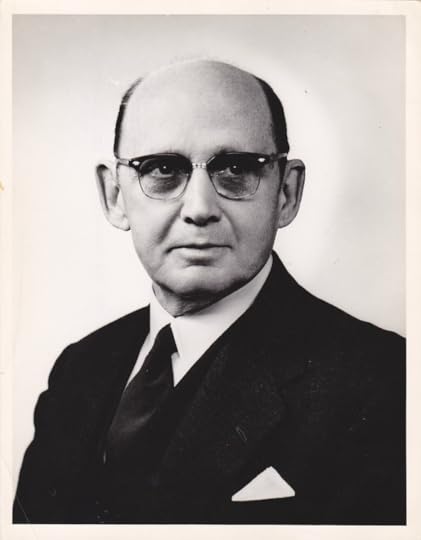

A diplomat's memories of Texas Jack Junior.

From the Abilene, Texas, Reporter-News, December 28, 1954.

SOUTH AFRICA'S AMBASSADOR ALREADY KNOWS ABOUT TEXAS

"You're from Texas?" the new ambassador from South Africa asked the other night when introduced to a fellow from the Lone Star State. "That is the biggest and best place in the world, isn't it?"

His Excellency Elmer Holloway, the Union of South Africa's Ambassador and Plenipotentiary, to use the full title, was obviously off on the right diplomatic foot, although he has been in the U.S. for only a few months.

"I have a reason for knowing how great Texas and its people are," he continued.

He had a story to tell.

It was about Texas Jack. He didn't know Jack's full name because even though almost everyone in South Africa knew him, no one knew any more of a name than Texas Jack.

Jack had come to South Africa around the turn of the century to start a circus. It was primarily an animal circus, and Jack took it on tours through primitive areas to get from town to town in South Africa and delight thousands of children.

The ambassador and his wife got to know Jack well. Then one day word got to them that Texas Jack was dying of tuberculosis.

"I went to see him," Ambassador Holloway said, "and found him lying on a cot seriously ill. By his side was a long whip made of cowhide, and, of course, I asked him why he had it."

Texas Jack told him he had to keep it at his side "because of that blasted turkey cock."

The wild turkey had access to Texas Jack's house and would frequently run to his cot to attack him.

"'Why don't you have someone cut off his bloody head?' I asked Texas Jack," Ambassador Holloway said. "Texas Jack said to me, "No, not that—I couldn't stay alive if I didn't know I had to fight that turkey cock."

The bird was smart enough to know that when Jack was coughing hardest, he was his weakest. So that is when the bird would go on the attack.

"But Texas Jack was always able to keep him away, and he died there without that bird ever having done him any serious harm," the ambassador said. "It was real courage."

The ambassador actually doesn't look the role of a diplomat physically. He looks more like the sort of man you would expect to see running a drug store on the square of a small Texas county seat than a foreign envoy with a ribbon across the chest.

Talking on, the ambassador said he has never had the opportunity to visit Texas—but he hopes he can before very long.

"I would love to see Texas," he said. "I have great respect for Texans and want to meet more of them."

December 8, 2022

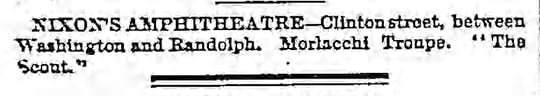

The Star of the Show

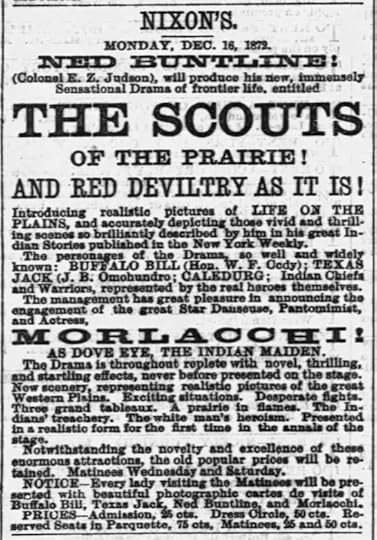

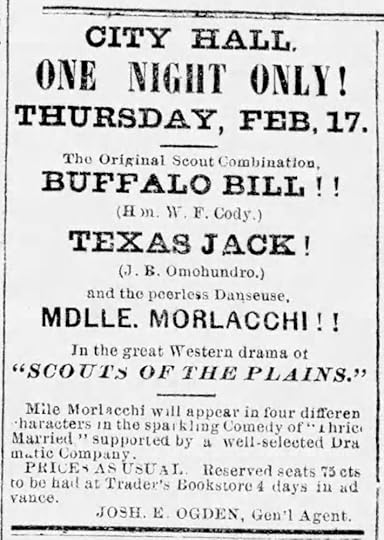

Because we know how famous Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack would become, it's easy for us to forget that they were relatively unknown to theater audiences before their debut on December 16, 1872. In fact, they weren't even the stars of their own show. As Texas Jack Omohundro and Buffalo Bill Cody wrapped up their affairs and made their final preparations to leave the Nebraska frontier and head to Chicago, the most famous ballerina in the world, Giuseppina Morlacchi, was in that city at the end of a run of shows at Nixon's Amphitheatre.

Though Morlacchi and her troupe had met great acclaim from New York to California, her run in Chicago had not been a particularly successful one. The city's critics praised Morlacchi's talents but noted that the local musicians in the orchestra were inadequate to support such a star.

Frustrated, Morlacchi and her manager and agent John M. Burke were urged by theatre owner Jim Nixon to accept a meeting with Ned Buntline, who was in talks with Nixon to premier his play at the Amphitheatre later in December. Though she was in demand as a ballerina at every opera house in the country, Morlacchi was intrigued at the chance to act on stage outside of the confines of the ballet—to engage the audience in a speaking part as an actor and not just as a dancer. She agreed to the meeting and eventually accepted the role of Dove Eye, the Indian maiden with a fondness for handsome scouts at the center of Buntline's play.

Early newspaper notices for the show don't even mention Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack. They simply note that the Morlacchi Troupe will be appearing in a play called "The Scout" at Nixon's Amphitheatre. And as the day got closer and Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack's names were added to advertisements, it was still "the great Star Danseuses, Pantomimist, and Actress Morlacchi" whose name was prominently displayed in every major Chicago newspaper. Little was she to know just how much the role would change her life and how much life would imitate art as she fell in love with the handsome cowboy turned scout Texas Jack.

December 6, 2022

Texas Jack in War Paint

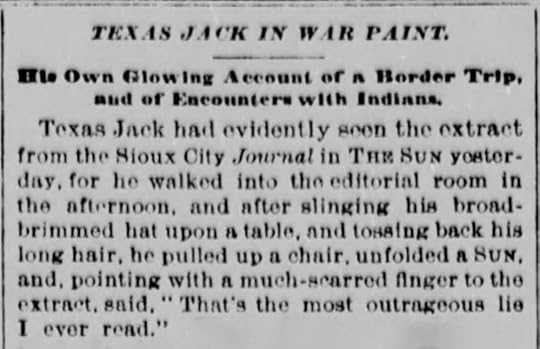

It was a quiet Monday afternoon at the Printing House Square offices of the New York Sun newspaper in late October of 1877. An editor sat working at his desk when he heard the heavy footsteps of a pair of leather cavalry boots approaching. As he looked up from his work, the editor saw a tall man in a fringed buckskin jacket and a large Stetson hat approaching with a folded newspaper in his hand. The man's eyes were focused on the editor and his lips were drawn into a frown beneath his mustache.

The man removed his hat and flung it on the editor's desk before dragging a nearby chair over, unfolding the copy of the paper he was carrying and placing it in front of the editor, and pointing to an article with a scarred finger.

"That's the most outrageous lie I ever read," said the man.

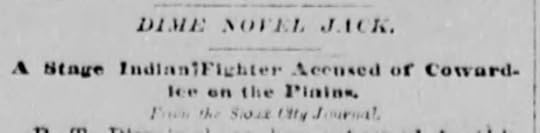

The editor quickly scanned the article in question, an extract from the prior day's edition of the Sun, reprinted from the Sioux City Weekly Journal. The article was about a British Army Captain and his aristocratic guest who had recently visited Sioux City after a long trek through the wildest parts of Wyoming.

"B. T. Birmingham has returned to this city from Rawlins, Wyoming, where he has been collecting specimens to send to England. He and Captain Bayley will be remembered as the two Englishmen who left this city in the early summer for the great unknown country of our Northwestern frontier, under the guidance of the notorious Texas Jack. If they should ever go again, they would not go under the guidance of Texas Jack.

When they employed him it was with the understanding that he had been all through Yellowstone Park and the adjacent regions, but it was discovered that, instead of his having explored even the Park, he had simply gone on the ordinary wagon road as far as the Mud Volcano, and then returned the same way. He professed full information in regard to the Geysers, but the only knowledge he exhibited was what he had probably collected from books and magazines. The result is that he was no guide whatever for the party, either in the Park or in the surrounding country—in fact, he had them lost for three weeks.

Jack is a fair shot when he has his gun leveled at clawless game; but when it comes to attacking anything which is able to fight, he prefers to let it alone. By some correspondences forwarded to Eastern papers, he sought to make it appear that in a contest with two grizzlies he gave the Englishman a sample of what real courage is. The real circumstances were that he didn’t want to stir the bears up, but Birmingham told him that it was for just such fun he had taken the trip; and so while Jack held his horse the Englishman slipped up and killed one of the animals, wounded the other, and pursued it into the sagebrush. This and other episodes knocked the stilts from under Jack’s pretensions of being a hunter.

Fortunately for the party, there was not much difficulty with the Indians during the trip. When within about thirty miles of Bozeman, it was feared that there was some danger, and Jack then wanted to leave the party. He was told that right then was the time he was most needed because every man counted when it came to such a conflict as appeared to be imminent. He replied that he could look out for himself, and the rest might do the same for themselves, and he quit the party abruptly in the very contingency for which he had been engaged as guide and guard.

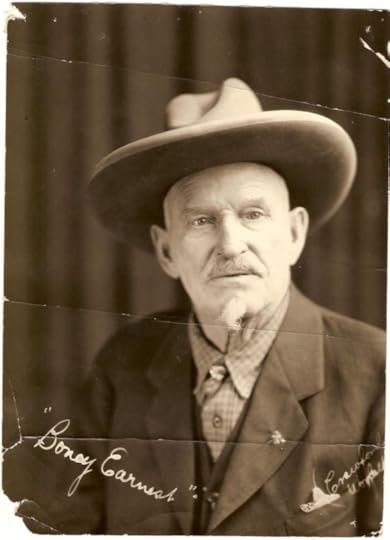

From this, his employers came to the conclusion that the stories about Texas Jack being such a terrific Indian fighter are rather on the dime novel order. They met two other guides, who exhibited real bravery and acquaintance with their surroundings. These were Boney Earnest and Tom Sun, both of whom make their headquarters at Fort Fred Steele. These old hunters made no boast of their prowess, but were on hand in every difficulty, while Jack’s chief glories were won with his tongue. He is now in the East displaying them on the stage, where there is no chance to disprove his claims in actual service."

The editor finished reading and looked back to Texas Jack, who had put his feet up on the corner of the desk while waiting, but now stood up and leaned over to tap the headline of the article, in bold black letters of the Sunday edition, that read "Dime Novel Jack - A Stage Indian Fighter Accused of Cowardice on the Plains."

“It’s a lie from beginning to end," exclaimed Jack, "and I can’t see how any man could have the cheek to write it.” The editor mildly suggested that perhaps the language in the article was a little strong, but was interrupted by Jack pointing again to one word in the article—six letters that he could not abide. Coward. Jack pounded the editor's desk with his fist as he expressed his rage at such an outrageous insult. When the editor asked how he could help correct the record, Jack's temper cooled and he sat back down.

“I ain’t much of a newspaper man,” Jack said, “but I can tell the story and you can take it down and fix it just as you want to. That’s what I say—that’s a lie. I would be willing to wager a year’s salary that I know that country of which this thing speaks better than any living man, and yet this thing makes it out that I don’t know anything at all about it.

“I’ll tell you my connection with that party of Englishmen, and of that trip. I told ’em when we started that no man knew definitely the route to the Geysers; but I could and would take them safely through to the Yellowstone Park; and I did it. I can’t understand how any person could get up such a tissue of barefaced lies, for all their statements I can prove to be untrue.

“In the first place—in the first place it is stated that I had never gone to the Mud Volcanoes, as a guide, through the wilderness, but simply by the ordinary wagon road. Now I can prove beyond all question that there isn’t a wagon road within twenty miles of the Mud Geysers. Again, I can prove that I took the men without trouble right to the Mud Volcanoes, and then we were jumped by the Nez Perce Indians. I took them safely out of the basin just in time, for we had barely left the region when the Cowan and Carpenter party were massacred. The very day, in fact, on which we left the basin the other party were shot down. We made a long march that day of twenty-six miles, and went into camp after I had gone out and killed a deer for our supper.

"The article says that I was afraid to tackle a grizzly bar. That is the biggest lie of all. I’ll take my Bible oath that of all the bars killed on the trip, I killed more than half single-handed.”

“How many were killed?” asked the editor.

“About twenty-two, and I’ll bet I killed nearly twenty. Now, on the day when they said I refused to go out with Birmingham to tackle a grizzie, I was sick in camp, and I had also had a row with him in the morning on account of words he had given me. That same day I was attacked by a bar, the biggest I ever saw—must have weighed over 2,200 pounds. I wounded him, and he clawed me, and I just escaped with my life.

“About my wishing to leave the party, it is just here. On the very day when I was expected to be on a Chicago stage practicing with imitation Indians in my play, I was in the heart of the wilderness surrounded with Nez Perces. With our repeating rifles we kept them at bay from a rampart of the rocks, and I took them safely, with all my pack horses, twelve in number, out of the reach of the redskins. Every other party in the region either lost their lives or had their stock stampeded.

“And yet this article says that as an Indian fighter I am no good? I telegraphed my wife that I had escaped the massacre, as it was reported that I had been killed together with my party. I also sent word to my manager in Chicago that I would be in that city on a certain day, and then I told my party that I must go back to the settlement at once. On the strength of this, it is asserted that I wanted to desert my party.”

“Where did you leave them?” the editor probed.

“I saw my party safe in Bozeman before I left them. On the way to that place, I escorted Mrs. Cowan and Miss Ida Carpenter, who had escaped the massacre. I protected the rear, and several times we were fired on by Nez Perces Indians. I had my stirrup shot away and a ball shot through my hand. Right here, see. It isn’t healed yet.”

Texas Jack showed the editor the fresh bullet wound on his hand before he left, and the editor assured the cowboy-turned-actor that he would print Jack's story verbatim in the next day's edition. Jack returned to his hotel and wrote a letter to the Sioux City Journal, which had printed the original story.

Journal Editor,

Though I may not lay all actual blame to you for the publication of the cowardly and scandalous article about me which appeared in your paper some time since, I ask you to do me the justice to contradict it. If you do not see fit to do this, at least do me the justice to give me the name of your informant. I suspect that the information was given by B. T. Birmingham, whom I consider to be a renegade Englishman, and because I did not give him credit for acts of bravery that he never performed, he has taken a mean advantage of my absence, which he never would have dared to have done had I been in his neighborhood.

Birmingham wanted me to put his name in the papers some time since and I refused, but now I will oblige him, and when he sees it in the different papers throughout the United States he will regret the fact that he ever tried to injure me. Let me further add that I regard Capt. Bayley as a perfect gentleman, and I greatly wonder that he should ever have been mixed up with such a blot upon the western frontier as Birmingham.

If you will take the trouble to interview Boney Earnest and Tom Sun, they will vouch for the fact that I have always proved myself what I represented myself—a man, a gentleman, and a scout. And let me further add that I denounce all of Birmingham’s statements as a tissue of lies. In regard to all Indian difficulties, I refer to Mr. Frank Carpenter and his two sisters, Mrs. Emma Cowan and Miss Ida Carpenter. If they do not say that I aided them during the Nez Perces [sic] trouble, then I am willing that I should not be considered what I now am.

Permit me to state further that my character can and will be vouched for by any of the old frontiersmen, or any of the army officers with whom I have served as guide.

Respectfully,

J. B. Omohundro

TEXAS JACK

Boney Earnest, the other scout who had joined Texas Jack on the expedition, was later interviewed by another paper and his story backed up Texas Jack's, as did the story of Frank Carpenter, whose brother-in-law was shot by the Nez Perce and who escaped with his sisters under the watchful guidance of Omohundro.

The vast majority of news articles were not attributed to their authors, and this allowed reporters the option of penning damning and libelous reports without fear of reprisal. It was not often that the subject of such pieces walked into the editorial room, flung his Stetson down, pounded his fist on the desk, and demanded that his version of events be given column space in order to clear his name. It seems that Texas Jack took questions of his integrity personally and saw anything that damaged his public reputation as a threat to his livelihood, both in the wilderness and on the stage.

November 18, 2022

Buffalo Bill & Texas Jack

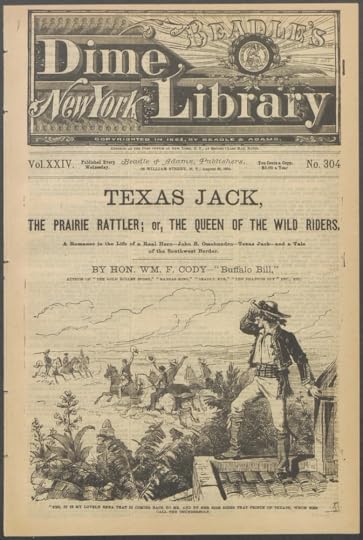

Three years after his best friend Texas Jack's death in 1880, Buffalo Bill was feeling nostalgic. He had just launched the Wild West Show, a spectacular outdoor version of the stage plays he began with Jack back in 1872. Between shows, as the cast and crew traveled by train to cities and towns across America, Cody wrote a story about his friend's time as a Texas cowboy after the Civil War. The story was one of the first to feature a cowboy hero, and shows both the warm affection and admiration Cody held for his old friend and partner on stage and trail Texas Jack.

Here is Cody's introduction of Texas Jack in his novel, Texas Jack, the Prairie Rattler:

The Texan was also well mounted upon a clay-bank horse, with a long silver mane and tail, and every indication of speed and bottom, though he had a vicious look in his eyes as he glared at the animal ridden by the Mexican.

His saddle and bridle were of elegant workmanship, studded with silver, trimmed with the skins of wild animals, and with a long lariat coiled around the horn.

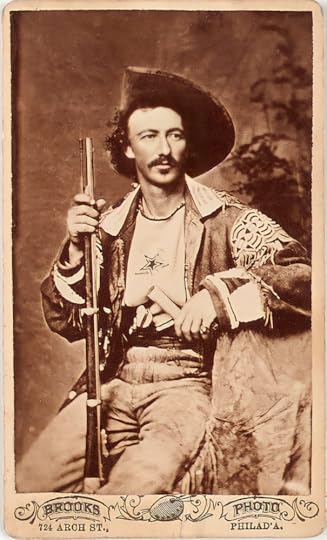

The rider was J. B. Omohundro —Texas Jack — a man whose life upon the southwest prairies and the northern plains has been one long scene of adventure, and of reality that casts romance in shadow.

A man of superb physique, wiry as an Indian and as untiring, he had a handsome face, full of light-heartedness, as though he looked ever upon the sunny side of life, and yet every feature was stamped with character, and the merry twinkle of his eyes could change in an instant into a deadly light, the smiling, reckless mouth become as firm as adamant.

He was dressed in buckskin leggings, stuck in cavalry boots, the heels of which were armed with massive spurs of solid gold which jingled at every movement of his feet; a velvet jacket, adorned with buttons innumerable, a la Mexican, a gray shirt with a black silk scarf knotted sailor fashion, and a broad-brimmed sombrero, the rim and crown encircled with an embroidered wreath in gold thread, and a large gold five-point star looping it up upon one side.

Certainly, he was a striking-looking man, whether met on the prairie or in the town, and, with the repeating rifle slung at his back, and his belt of arms, a most formidable-looking adversary.

In Buffalo Bill's story and with his Wild West show, he tried to tell the world about the kind of man his cowboy friend Texas Jack had been. In early 1917 — 34 years after he wrote this story, 45 years after he and his friend launched their careers as showmen, and nearly 50 years after they met on the frontier prairie of Nebraska — a train carrying the weak and ailing Buffalo Bill Cody stopped in Leadville, Colorado, on the way back to Denver. Not strong enough to leave his bed, Bill sat up to tell his daughter about the gravemarker he had planted in the town's cemetery, marking the final resting place of his best friend, his first partner, his staunchest ally — Texas Jack.

Four days later, Buffalo Bill was dead. He outlived Jack by almost 37 years, entertaining hundreds of thousands of people and becoming the most famous showman on the planet. But he never stopped telling his friend's story.

November 17, 2022

Filling In The Blanks

I maintain a list of known Texas Jack performances, both with Buffalo Bill and Wild Bill and with his own combination, over at www.texasjack.org/map.

And as complete as that list is, there are plenty of blanks, and sometimes we don't know if those blanks are because the show took a night off, or there simply isn't documentation of shows played in smaller towns whose newspapers haven't been archived online. For example, we know that Texas Jack and Buffalo Bill were in Richmond, Indiana on the 15th of February, 1876. We also know that they were in Columbus, Ohio, four days later on the 19th. But we didn't know if they relaxed for those four days or played a show at a stop between the two cities. Dayton and Springfield seem like the two most likely stops, but no evidence for stops in either has come up in online newspaper archives.

Until now.

Just recently, the online archive newspapers.com has been updated with records from the town of Xenia, Ohio, just southeast of Dayton. An ad from the February 15th edition of the Xenia Gazette shows us that Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack, along with Jack's wife the Peerless Morlacchi, played the "City of Hospitality's" City Hall on the night of February 17th.

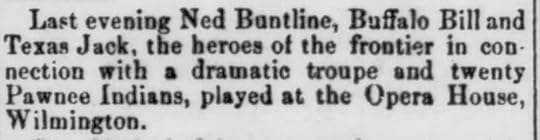

Similarly, archived editions of the Smyrna Times newspaper in Smyrna, Delaware, fill in a previously blank date on May 20, 1873, on Texas Jack and Buffalo Bill's first tour with Ned Buntline. The Scouts weren't in Smyrna, but a brief article in the Times tells us that they were playing Wilmington the night before.

Looking at the long list of the hundreds of cities that Texas Jack, his wife, and his friends played between December 1872 when he launched his career as a showman in Chicago, and his final shows in Leadville in April of 1880, its apparent just how indefatigable this cowboy was. And its no wonder that his career laid the groundwork and set the stage for all showbiz cowboys who followed.

November 15, 2022

The Most Valuable Image of Buffalo Bill

Is this the most valuable image of Buffalo Bill Cody in the world? Experts estimate that it could fetch upwards of $15 Million at auction on Thursday, when it hits the auction block at Christie's in New York.

Buffalo Bill is an example of "Analytical Cubism" painted by world-famous artist Pablo Picasso in 1911, just six years before Bill Cody's death. Picasso probably caught Buffalo Bill's Wild West in Paris in 1905, the second visit the show made to the "City of Lights," the first being a five-month visit in the summer of 1889. Picasso was taken by Cody and his show, and for the rest of his life maintained a love of cowboy accouterments like lassos, Stetsons, and revolvers and occasionally signed letters "Pard."

This painting was purchased by one of Picasso's earliest and most enthusiastic supporters, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler. It was last sold at Sotheby’s auction house in London in 1986, and has remained in private hands, though it was a prominent part of the MoMA's 1989-90 exhibition, “Picasso and Braque, Pioneering Cubism.”Picasso wasn't the only European artist influenced by Buffalo Bill. The scores of Cody's admirers included several who actually saw the great scout perform live. Rosa Bonheur was allowed to sketch and paint the animals that were part of the show and painted a striking portrait of Buffalo Bill as a gift to thank him for allowing her such unfettered access. “Buffalo Bill was extremely good to me,” she later recalled. “I drew studies of [his] buffaloes, horses, and weapons, all tremendously interesting.”

“[I] walk about like a savage, with long hair,” painter Paul Gauguin wrote the summer after visiting Buffalo Bill's Wild West in Paris in 1889. “I have cut some arrows and amuse myself on the sands by shooting them just like Buffalo Bill.” When Gauguin left France for Tahiti, he wore a prized Stetson purchased after watching the cowboys perform in Cody's show.When Picasso's Buffalo Bill hits the auction block on Thursday, we'll see if this is the most valuable and expensive image of Cody in history.

November 9, 2022

Chief of Men

This is Pitaresaru (Chief of Men), who was the leader of the Chaui band of the Pawnee and head chief of the Pawnee. During the years Texas Jack spent at Fort McPherson, he and the Pawnee men, especially Pitaresaru, became close friends.

It's easy to dismiss western scouts like Texas Jack and his friends Buffalo Bill Cody and Wild Bill Hickok as "Indian fighters." They all served as western scouts, and scouting the open prairies and plains of the American West came with its share of hostile encounters. But it is interesting that in the cases of Texas Jack and Buffalo Bill, they became fast friends with many Native people despite their public reputations. Buffalo Bill employed many Sioux performers in his Wild West Show, and Texas Jack was close friends with Warm Springs scout and chief Donald McKay and his daughter Minnie.

Texas Jack spent part of his time in Nebraska with Pawnee, learning their language and signs, and was chosen to accompany the Pawnee during their annual buffalo hunt in 1872. He wrote fondly of his time hunting with Pitaresaru, who Jack called "Old Peter," and his new Pawnee friends.

While the Pawnee showed Jack how to hunt buffalo with bow and arrow, he showed them the lasso tricks he had picked up as a cowboy on the Chisholm Trail. The Pawnee nicknamed Texas Jack ruukiraahak awikiickawarik, or "Whirling Rope," in appreciation for his skills.

Pitaresaru requested that Texas Jack join him and the tribe on their next hunt, but the government agent delayed authorizing the request for so long that Jack decided to travel to Chicago with Buffalo Bill to try their hands at show business. The agent assigned a greenhorn to accompany the Pawnee, leading to their fateful encounter with their Sioux enemies at Massacre Canyon, and their subsequent departure from Nebraska to their new reservation in present-day Oklahoma.

The tragic loss of life suffered by the Pawnee weighed heavily on Texas Jack Omohundro. He had grown close to Pitaresaru, who he called Old Peter, and some of the braves while on the hunt the previous summer, both parties finding amusement in the hunting style of the other. The thought that he might have been able to prevent their deaths troubled Jack profoundly. According to an interviewer who talked to Jack just after Massacre Canyon, “Texas Jack says his sympathies are with the Pawnees in their fight with the Sioux, and he hopes the government will interfere on behalf of the Pawnees, as they are inferior in number to the Sioux.”

October 19, 2022

The Scouts in Richmond

On Monday Evening, October 18th, 1875, the "Original Select Combination" starring Buffalo Bill Cody, Texas Jack Omohundro, and the Peerless M'lle Morlacchi played the Richmond Theatre. Anticipation for the show was high, especially amongst the town's young men and boys.

One paper reported that "an unusual number of boys have applied to our office during the past week to sell papers. Their motive was at once apparent, and they did not hesitate to express their reasons for it—they said they wanted to make money enough to buy tickets to see Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack."

While the boys were hustling to make enough to see the famous scout Buffalo Bill and the famous cowboy Texas Jack, their parents were excited for a chance to see Texas Jack's famous wife, the Italian ballerina Giuseppina Morlacchi. They had read reviews of the show in newspapers like the Wilmington, North Carolina, Daily Review, which said "The charming little danseuse and actress M'lle. Morlacchi sustained four different parts in the first piece, in each of which she was received with tumultuous applause, and her supporters added spirit and interest to the scenes. "The Morlacchi" as a danseuse is simply excellent. The versatility of M'lle Morlacchi proves her the possessor of considerable talent, and her dancing was especially pleasing."

The Richmond Theatre was packed to capacity that night, just like theatres in the twenty-some-odd cities the show had played since opening at the end of August in Philadelphia. That October night in Richmond, it is likely that neither Texas Jack nor Buffalo Bill knew that this tour would be their last one together. The tour would continue into the following year, and as the winter of 1875 turned into the spring of 1876, Buffalo Bill's son, Kit Carson Cody, would die of scarlet fever on April 20th at the age of five. Devastated by the loss, Cody was committed to finishing the tour, which played more than 80 cities after that October show in Richmond, ending on July 3, 1876, in Wilmington, Delaware. By that night, the final time Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack would step on stage together, Cody was ready to leave his showman life behind for good, settling down following the loss of his son to spend more time with his wife and his daughters. The death of General George Armstrong Custer at Little Bighorn at the end of the month and Cody's subsequent involvement in the pursuit of Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull spurred him back towards the stage, but without the help of his best friend and stage partner Texas Jack.

They had launched the first stage western together at the end of 1872, neither entirely confident and neither, by all accounts, a capable actor. But the scout Buffalo Bill and the cowboy Texas Jack had combined their former professions, their experiences in the American West, and their personalities into something that would outlast them both. They created the western, the great American story that had been told and retold from the moment they stepped off the western frontier and onto the stage together, and the story they began is still being told today.