Matthew Kerns's Blog: The Dime Library, page 20

October 7, 2022

The Law in Hays

From the Burlington, Vermont, Burlington Free Press October 6, 1869.

We met at Fort Hays a somewhat notorious character named "Wild Bill." I recognized him at once from the picture of him which appeared in Harper's Magazine some time since. He is now Sheriff of Ellis County and Generals Sturgis and Custer tell me that it would be impossible to go into the town of Hays in the evening unarmed, except for the good order which "Wild Bill" preserves. But I must add that during a single night that I spent there, I heard several times the joyful" pop of the pistol.

Mr. Wild Bill, or Mr. Hickok, is one of the finest specimens of humanity, physically, that I ever saw; he stands, I should think, six feet and an inch; but such a pair of shoulders, and such depth of chest and breadth of hips are not often seen. He has a broad forehead, small clear blue eyes, a very sharply cut, small mouth, and a square, firm chin, altogether a very pleasant face for a friend. But one may easily imagine how that forehead could contract, those eyes snap, the lips form a straight line, the chin draw up slightly, making a face which would indicate a decidedly ugly customer.

I inquired particularly of General Sturgis in regard to the article in Harper's Magazine about "Wild Bill," and he told me that, though highly colored, it was substantially true. One thing Bill must have credit for, and that is being a very modest man. He is very indignant at being made a lion of, and uses rather strong language with regard to the man who wrote the Harper's article, and various other articles that appeared since then.

September 30, 2022

Lawsuit

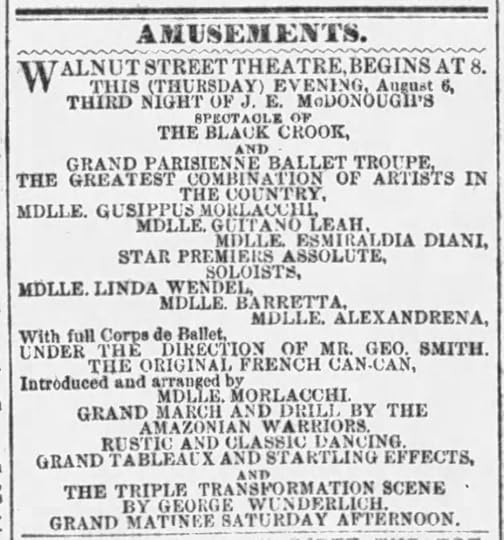

In December of 1868, Giuseppina Morlacchi was involved in a lawsuit in Philadelphia. The Philadelphia Inquirer newspaper of December 4, 1868 has the details:

Giuseppina Morlacchi vs. John E. McDonough.

This was quite an interesting suit, recalling recollections, pleasant or otherwise, of the departed Black Crook. The "Great Morlacchi" invoked the strong arm of the law to do her justice by bringing an action against Mr. McDonough to recover compensation for doing the Dancing Fairy three weeks for the Quaker City.

She alleged that during the past summer she made a three-month engagement with Mr. McDonough as principal danseuse in the Black Crook ballet, the contract being that for a sally of $200 per week she would dance for him at such "theatres as he might engage," when required by him, submitting to the general rules of the company; and she fulfilled her part of the agreement, but he refused to pay her for the three weeks she performed at the Walnut Street Theatre in August last,

The defense set up that while the theatre was being prepared for the production of the spectacle, Morlacchi was in Chicago, and Mr. McDonough telegraphed her to come to this city by the 17th of July, but she, not heeding his direction, postponed her arrival until the 20th, thus causing the Company to be idle three days, during which it might have been giving profitable performances in some of the neighboring towns. She had broken her engagement in disobeying the call of her employer, and he was, therefore, relieved from liability on his part.

But counsel for little Morlacchi argues that it would have been utterly impossible to have arranged any unprepared stage for this piece in three days, and he had not shown that he intended its performance anywhere else; moreover, the express terms of the contract were that she should dance at any theatre he might have engaged and prepared, and he did not have the Walnut Street Theatre ready until the 3rd of August, and, therefore, until that time he was not entitled to a single wag of her toe.

The jury rendered a verdict for the plaintiff for $612.

September 22, 2022

See Saw

This article appeared in the Leadville Daily Herald on September 21, 1882, two years after the death of Texas Jack. John M. Burke was Giuseppina Morlacchi's business manager for several years before 1872, when she joined Texas Jack and his friends Buffalo Bill and Ned Buntline to star in the first stage western, The Scouts of the Prairie. Burke later starred alongside Texas Jack as "Arizona John" for several years, and in 1886 began working again with Buffalo Bill as the promotional manager of The Wild West, a post he would man until 1917, when first Buffalo Bill and later John Burke himself died.

Here, two years after Jack was buried in Leadville's Evergreen Cemetery, Burke notes the deteriorating conditions of Jack's grave and tombstone. The grave marker Burke mentions here was actually stolen from the cemetery, as was the replacement. When Burke returned with Buffalo Bill Cody twenty-six years later, Texas Jack was on his fourth grave marker. Cody and Burke together ensured that Texas Jack was given a fitting memorial, the one that still marks the famous cowboy's final resting place.

From The Leadville Daily Herald, September 21, 1882:

“Twenty years in the profession,” remarked Manager J. M. Burke, of “Old Shipmates,” as he knocked the ashes nonchalantly off the end of his cigar and sent a puff of blue smoke curling up into the otherwise blue ether, “does give a man a little experience with the ups and downs of the life, for let me tell you all is not plain sailing by any manner of means,” and with this the jolly manager patted the HERALD representative good-naturedly on the shoulder, and, leaning back in the carriage, indulged in a good-natured, hearty laugh. The manager and the HERALD man were, at the time the observation quoted above was made, driving towards Evergreen cemetery, where lies buried all that remains earthly of what was but a short couple of years ago one of the finest forms that ever graced manhood’s crown; the remains of one who, had he but taken care of himself, might to-day have been to the fore, and who as it is still lives in the remembrance of all those who appreciate the freedom of frontier life and admire those types of superb physical manhood who became the pioneers of civilization and who, as government scouts and hunters, led the white man step by step into the haunts of the red man and fastnesses where alone the wild game of the Rockies found safety and pasture. It was the grave of John B. Omohundro, better known as “Texas Jack,” the manager and his companion were about to visit, who, all forgotten, or at least uncared for, lies entombed in the bosom of the eternal mountains.

“Give me a sketch of your career,” here interrupted the reporter. This the manager, one of the most modest of men, was at first rather loth to do, and without further preamble gave the following interesting sketch of a professional life that is filled with so piquant an interest as to afford more than an ample apology for its publication.

“Yes; I started out in my theatrical career in the season of 1863 and 1864 at Washington. My first role was that of treasurer of Grover’s theatre there. It was a very exciting period in the history of this nation, and my position naturally brought me in contact with all the great men of the day. The president — Lincoln — I of course knew well. He was a great theatre goer. His assassin, Wilkes Booth, was also a friend of mine, and I remember as if it were only yesterday seeing Booth ride up Four-and-a-Half street on Jim Humphreys’ mare. But enough on that head. Even after this length of time the subject is too painful a one for me to care to dwell on.

"Being in Washington and meeting so many politicians of the day, it is hardly to be wondered at if I became somewhat enamored of public life, so much so, indeed, that when Congressman Green Clay Smith, of Kentucky, who had been appointed to succeed Thomas Francis Meagher as governor of Montana, offered to make me his confidential secretary I jumped at the offer and accompanied him up the Missouri River to Nebraska City. Here our journey was brought to an abrupt termination, as no cavalry escort could be spared to accompany the governor at that time, who was therefore compelled to postpone his journey until the following spring. It was at that time I first heard of Denver, Colorado, which was then looked upon as a sort of oasis in the great desert which lay between the civilized portion of the United States and what is to-day the great west, and in a vague sort of way got an idea of the vastness of the territory into which civilization was pushing so steadily forward.

"On getting back once again to Washington I became associated with C. D. Hess, who was at that time running the Pittsburg theatre, and under his management made my first bow before an enlightened and critical audience as Rosencrans in Hamlet, E. L. Davenport being in the leading role. After these lapse of years it may not be egotistical for me to state that Davenport, after the curtain had fallen, came forward and personally congratulated me upon my interpretation of the role. Hess and I became good friends after that and I remained with him several seasons, occupying the dual role of assistant manager and actor. Finally, we separated and I became a wandering showman in more senses than one, taking charge of a series of Japanese and Arabian combinations, which just at that time were touring the United States.

"As a manager of these, I was not, financially considered, a success, one after another of the companies falling to pieces or into the sheriff’s hands for lack of alimentary paper. This kind of thing could not go on for ever, and I finally determined to confine myself entirely to business management. This determination proved a wise one, for the next venture with which I became associated proved a great financial, as well as theatrical, success. It was the management of M’dmlle Morlacchi and her ballet troupe, which was then the leading terpsichorean venture of the day. Money though in those days was not made quite as quickly as it is now in the theatrical profession, and M’dmlle’s $50,000 clear profit in the live seasons, during which she was under my management, may therefore be considered phenomenal.

"While managing Morlacchi, we toured across the Rockies to San Francisco. On the return journey, happening to stay over at North Platte, Nebraska, with the company, I accidentally met and was introduced to W. F. Cody (Buffalo Bill) and John B. Omohundro (Texas Jack). The following season we played in Chicago at Nixon’s Amphitheatre, and, by chance, Ned Buntline, with Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack, who were to follow us, arrived there while M’dmlle was still playing. Buntline, properly speaking, had no theatrical organization at that time of his own, but so soon as he saw M’dmlle play Naramaiah in “Wept of the Weptonwich,” a standard character in those days, founded on the story of the romance of The Last of the Mohicans, then he conceived the idea of writing a play in which M’dmlle should be the central figure, and which should also introduce his two great western celebrities, Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack. When the proposition was made to M’dmlle Morlacchi, it, for some reason, pleased her greatly, and Buntline set to work and wrote the play. I took charge of the company and from the very start scored an immense success, and every one was well satisfied.

"One of the unforeseen outcomes of the associations thus unconsciously brought about, though, was M’dmlle’s marriage to Texas Jack. Theirs was a regular love match, and for a time they lived most happily together. After a time though the combination dissolved, Jack and his wife retiring from the stage for a while, Buffalo Bill to start on his own account, and your humble servant to seek fields and pastures new on which to gain further managerial honors.

"Behold me, therefore, when next I claimed public attention in command of McDonough & Earnshaw’s Wooden-Headed Marionettes. This was a great show and took the public fancy, and as the public interest increased, so in equal ratio did our financial success, until, I, the manager, attained the height of my managerial ambition. Finally the Marionettes departed to Australia. Boynton-suits not having, in those days, been invented, I declined to cross the briny ocean, and remained behind to mourn the departure of the most tractable theatrical combination that was ever boxed up and dispatched across the water or passed under a theatrical manager’s hands.

"My success with the Marionettes having been beyond all precedent, I, after a rest of several months, determined to once again try my hand at management. I wanted, however, a change from the ordinary routine of a theatrical business manager’s duties and so attempted to manage a circus. The company I selected after mature deliberation for the honor was that of the celebrated Dr. Thayer. Thayer’s circus really did require a business manager, and as I have already mentioned I wanted something novel, to me, to manage.

"That I believe is about all I have to say about his venture, unless indeed it be to remark by the way of a valedictory that as a circus manager I did not prove an overwhelming success; in fact, to be absolutely truthful, I proved somewhat of a failure, and way down the Ohio river somehow or another landed circus, manager and all in the hands of the sheriff. This experience, though not being entirely new to me, I did not take too much to heart, and after a respectable interval, during which I studied the dark side of nature pretty thoroughly, “bobbed up serenely” once again in charge of Bartley Campbell’s “Galloy Slave” troupe. Remaining with Campbell long enough to see him thoroughly on his feet, I thereafter attached myself to the fortunes of no less a personage than M. B. Curtis, whose “Samuel of Posen” has become one of the most popular character pieces of acting on the stage. When I took charge of “Samuel,” though, his success was by no means so assured, John T. Ford having made an unsuccessful attempt to float the novelty and the actor.

"With “Samuel” I remained until he began his western tour, in addition to the business management playing the part of Old Winslow, the jeweler, in the play, and just here I may casually remark that, in addition to the business management of many of the pieces I have been connected with, I also took a role, as, for example, with Ned Buntline, where, as Arizona John, I became quite a favorite with the theatre-going public of the day, and, perhaps, it was in appreciation of my talents more as an actor than business manager that Buffalo Bill presented me, many years ago, with the cane I am carrying in my hand to-day.” [The cane is a very handsome ebony one, gold mounted, and bears a characteristic inscription of the donor’s appreciation of the manager.]

“My latest managerial venture is “Old Shipmates.” When I took charge, the drama, though successful as a play, had not begun to be so financially. What it has become you are as well able to appreciate as I am.”

At this moment the carriage, which had been driving slowly through the cemetery grounds, stopped in front of the grave that, save for a border of small stones and a little wooden headboard, was unmarked. “This,” remarked the sexton, “is the grave you are looking for,” and the manager thereupon left the carriage and, bareheaded, approached the grave. There was an inscription on the headboard which he, kneeling down, deciphered with difficulty, for it had been written in pencil and the storms of a winter and heats of a summer had done much to efface its clearness, the following touching epitaph in his wife’s handwriting:

JOHN B. OMOHUNDRO,

Dio te guarda mi querido alma,

Died June 26, 1880.

Tuva, hasta pronto,

‘Texas Jack.’

Guissepina Morlacchi.

They were the last lines penned by the hand of love, who sorrowing over “Jack’s” troubles and indiscretions and yet faithfully followed him through sunshine and sorrow to the grave, and, having laid him there, left him to God’s care and keeping; she could do no more.

Tears were in the manager’s eyes as he remounted. “Poor Jack,” he exclaimed. “He was his own worst enemy. Prosperity did not ruin him, but adversity drove him to the bottle and the bottle led him to an early grave.

“Do you know I can not bear to see his grave thus unmarked, and shall at once set about having a suitable monument erected to mark where lies “a man,” the noblest work of God.”

September 21, 2022

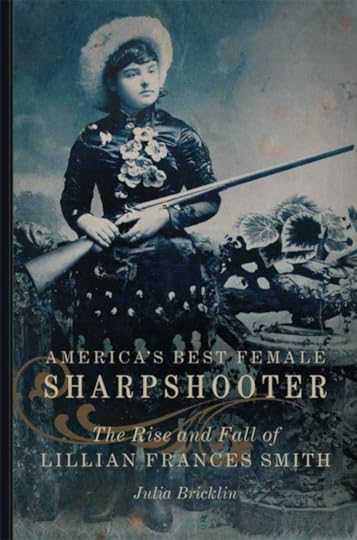

Review of America's Best Female Sharpshooter

America's Best Female Sharpshooter: The Rise and Fall of Lillian Frances Smith

by Julia Bricklin

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐A casual student of history might believe that Annie Oakley was a peerless shooter without a rival, standing alone amongst the famous names of western men renowned for their accuracy with pistol and rifle. This book sheds light on Lillian Frances Smith, who not only matched but often exceeded "Little Miss Sureshot" when it came to displays of incredible skill with her guns.

In the more than capable hands of Julia Bricklin, we learn that the reason history has remembered Oakley so fondly while ignoring the exploits of Smith is that Annie's image as a feminine, clean-living, happily married woman was much easier to package and market than her frequently less palatable rival. But we learn that while America more readily accepted pretty little Annie, Lillian was the better of the two when it came to her remarkable ability with her weapon.

The abilities and sensation of Lillian Frances Smith are attested by the fact that she, like Annie Oakley, was hand-picked by Buffalo Bill Cody, the preeminent showman of the age, to star in the traveling Wild West Show. Smith went on to reinvent herself several times over, transitioning from "California Girl" to Sioux princess "Wenona," rumored to be the daughter of Sitting Bull himself. Through periods of feast and famine, fame and misfortune, in romance and dire straights, Julia Bricklin walks us through the sometimes tragic but always interesting life of one of America's great forgotten stories.

Just like in her biography of Ned Buntline, Bricklin is able to concisely present a story of a person whose life wasn't always (if even often) pretty with humanity, not shying away from the bad decisions and moral failings but never condemning her subject. Presented in whole in the context of history, Lillian Francis Smith, like Ned Buntline, stands as a fascinating individual who rose to the very top of their milieu on their own terms, and who deserves to be remembered and written about by someone with the attention to detail and to the craft of writing that Bricklin so often displays.America's Best Female Sharpshooter: The Rise and Fall of Lillian Frances Smith by Julia Bricklin is available at:

September 18, 2022

The Scouts in Nashville

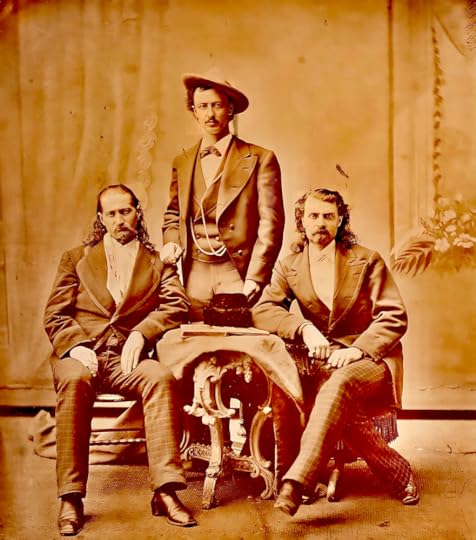

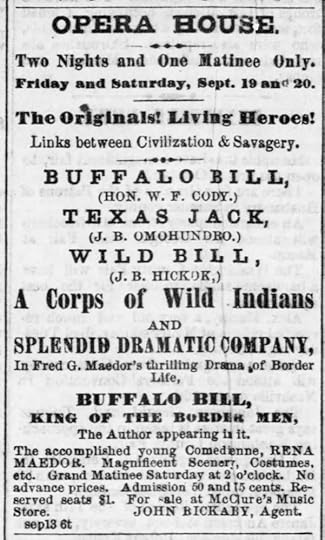

One September 19th and 20th, 1873, The Scouts of the Prairie played the Grand Opera House in Nashville, Tennessee.

Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack were now veterans of multi-day stops in nearly 70 different cities. During their first season they had been labeled as "bad actors" by newspapers in nearly every city they visited. They hadn't become better actors over the course of those shows, but they were what Bill Cody called "first class stars," who might not remember all their lines but were filly capable of drawing immense crowds and enchanting audiences with their "blood and thunder" drama. And as unpolished as Texas Jack and Buffalo Bill were as actors, he new addition to their cast was decidedly worse.

Wild Bill Hickok was perhaps the most famous western man in America, his exploits as a gunslinger and lawman having been read in newspapers and periodicals alike. Myth had already mixed with reality, and Hickok was larger than life almost from the moment he achieved any measure of widespread notoriety and fame. What he wasn't particularly good at was acting.

Buffalo Bill later wrote that "Wild Bill had a fine stage appearance and was a handsome fellow, and possessed a good strong voice, yet when he went upon the stage before an audience, it was almost impossible for him to utter a word. He insisted that we were making a set of fools of ourselves, and that we were the laughing-stock of the people. I replied that I did not care for that, as long as they came and bought tickets to see us."

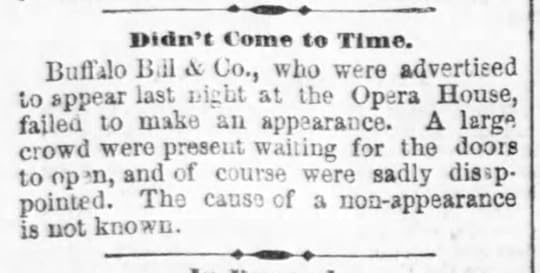

The scouts made their appearance as scheduled on the 19th, but the next night, with a large crowd waiting to be allowed into the Opera House, the show's cast and crew never showed. The Nashville Union and American newspaper reported that "Buffalo Bill and Company, who were advertised to appear last night at the Opera House, failed to make an appearance. A large crowd were present waiting for the doors to open, and of course were sadly disappointed. The cause of a non-appearance is not known."

The Scouts did manage to make their next scheduled show in Cincinnati, where a reporter filed this review:

"Buffalo Bill, King of the Bordermen was brought out to a full house last night...the material of the play consists of the regulation Dutch and Irish characters, a well-rouged heroine, six "Indian" supes, and the three stars: Buffalo Bill, Texas Jack, and Wild Bill—the "border" men, of which the first is the "King."

The Ninth-Street manager, to whose enterprise the town is indebted for this visitation, must be congratulated on having at last found something that pays, for the house last night scooped in every bootblack and corner loafer in town, but as their money is as good as anyone else's, certainly the manager is not in a position to complain.

"Buffalo Bill" is the connecting link between the scum of the cities and the scum of the plains, the mouthpiece of the unfledged ruffianism that requires the vigilance of the police the year round to keep within bounds.

Not one of the three principal roughs has the least notion of acting, for it is as much as any one of them is capable of to recite a simple English sentence, and on his natural level, if he got a position in a theater at all it would be at shoving scenes. It is as "border men," however, that they base a claim to intrude themselves on the community—as killers of half-breed Indians, and fighters about the drinking-shops of new settlements but here, too, they are weak, for there are in our midst , which is at the same time no cause for congratulation, any number of men who could beat them at that game. In our County Jail we have a quartette beside which they are nothing. Cody and his friends always fought, in well-armed gangs, against the effeminate, defenseless beggars of the prairies, while our "Wild Bill," in every case, killed his man in single fray, the victim, three times out of four, being the biggest man. It makes the difference, however, between savage and civilized life, that these brought are let loose to prey upon society, while ours are safely locked up, thus preventing other managers than the Sheriff from getting up a reveal sensation, and he would not be allowed to take money for it.

But there is one good side to the show. By exhibiting themselves, Cody, Omohundro, and Hickok make enough to buy refreshments, which otherwise they might be apt to get in a different way, thus relieving the traveler by night of much anxiety and the corporation treasury of expense. Therefore let them be treated as was old "Eccles" in the play—let them have a fair supply of money."

September 9, 2022

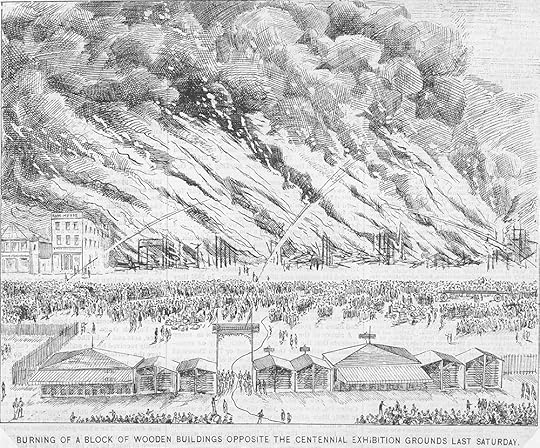

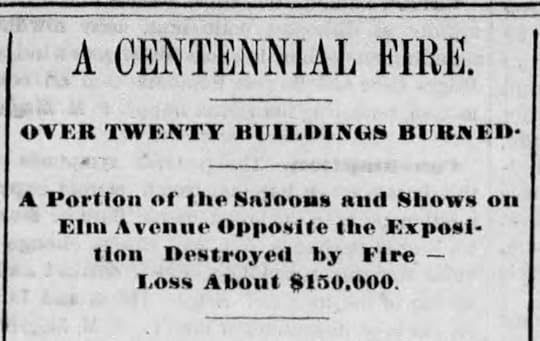

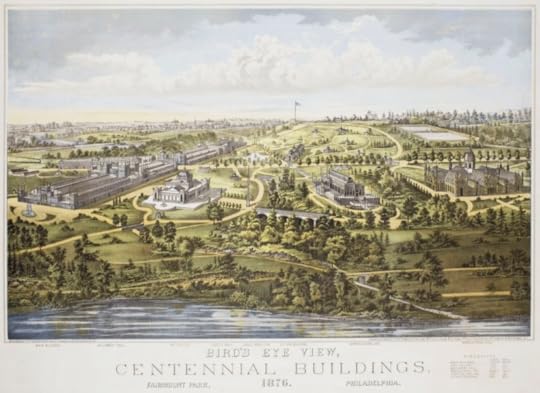

Shantytown Fire

There were only three legal buildings on Elm Avenue by September 9, 1876. Three buildings where the owners had filed permits, built properly, and operated legally. These were the Jourdan Brothers establishment at 4120 and 4122 Elm, the Elm Avenue Hotel, and Texas Jack’s Hunter's Home at 4188 Elm. All of the other buildings were cheaply made wood structures built haphazardly between these buildings and the larger hotels at the ends of the street. Just three legal buildings in an area with between 150 and 200 businesses, including hotels, ale houses, bootblacks, clothiers, booths and stalls catering to all tastes of the thousands visiting the Centennial grounds across the street.

The ramshackle appearance of many of these poorly constructed and illegally built businesses led to some calling the portion of Elm Avenue facing the Exhibition grounds at Fairmount Park "Shantytown." The illegal buildings must have concerned Texas Jack and his business partners as much as they did Philadelphia's mayor, who tried to get permission from the city council to tear down the illegal buildings for presenting a fire hazard.

Just after four p.m. on September 9, the day after the above report was printed, thousands of visitors near the entrance to the Centennial Exhibition noticed smoke rising south of them. Initial fears that the Main Building had caught fire were quickly dispelled, but as the throng of people rushed toward the fence, it became obvious that some of the wood buildings on the south side of Elm Avenue were on fire. The fire had begun at the Broadway Oyster House when a cook had grabbed a can of gasoline for the stove and carried it too close to the flame. The ensuing explosion quickly spread to encompass the surrounding buildings.

The first alarm went out from the nearby Globe Hotel at twenty minutes past four, but despite having shown their speed of response the day before by racing steam-powered fire engines down Elm Avenue, it was another twenty minutes before firefighters arrived to begin battling the blaze. When they ran their hoses to the nearest fire-plug, it was found to be clogged with sand and filth and had to be cleaned before it could be used at all. Fifteen minutes later a second alarm sounded from the United States Hotel further down Elm Avenue.

As the fire raced toward the Transcontinental Hotel to the west and the Ross House to the east, many of the one hundred thousand visitors crowding the park that Saturday gathered to watch the conflagration. The people packing the street made it hard for the firemen to move, and police were dispatched to push back the crowds. As the pine buildings burned, the flames became so hot that Exhibition fences across the street on the north side of the avenue were scorched. This heat made it impossible for the firemen to continue combating the flames. Two fire engines that had made it to the scene were kept inside the park fences, in case the winds shifted and made their way to the Main Building.

Buildings along Elm Avenue were consumed so quickly that most of the proprietors were only able to grab their cash boxes before escaping, leaving valuables and personal belongings to the flames. One zoological exhibition contained two sea lions in an enormous tank, which was far too heavy to move. Spectators watching the fire from inside the park reported hearing the animals crying above the noise. Blanchard’s Amazon Theatre, Wylie’s drinking pavilion, California Cheap John’s clothing and junk shop, and Madame Duclos’ female minstrels were all burned out, dancers of the latter being forced to flee in costume onto the Exhibition grounds. The fire’s eastward spread was halted by the solid brick walls of the Ross Building, though the interior of that building was consumed in the blaze as well.

The third alarm at a quarter to five was sounded from within the Exhibition grounds, as the fire continued to consume buildings along Elm Avenue. A bowling alley, a shoe shop, more beer saloons, restaurants, and a stable were consumed before firefighters were finally able to contain the flames. The following morning’s newspapers, in addition to recounting the story of the fire, pondered its origin. Arson, either on the part of the oyster house staff or from a city official determined to shut down the less-family-friendly establishments contained in the area, were the primary guesses as to the beginnings of the blaze.

The mayor wasted no time in sending crews to tear down all of the remaining buildings, legal or otherwise, including Texas Jack's Hunter's Home hotel. Jack, far to the northwest chasing Crazy Horse in the aftermath of the Little Bighorn battle, wouldn't learn of the fate of his hotel and his fortune for weeks. By then there was nothing left of either to salvage, and the trajectory of Jack's life changed. He had been convinced that this was his ticket out of constant touring, to starting a family and spending time in leisure with his wife. None of that was now possible, so after a frustrating campaign with General Terry, Jack headed west on a trek with Sir John Rae Reid and planned his next dramatic tour, his first without his friend Buffalo Bill.

September 8, 2022

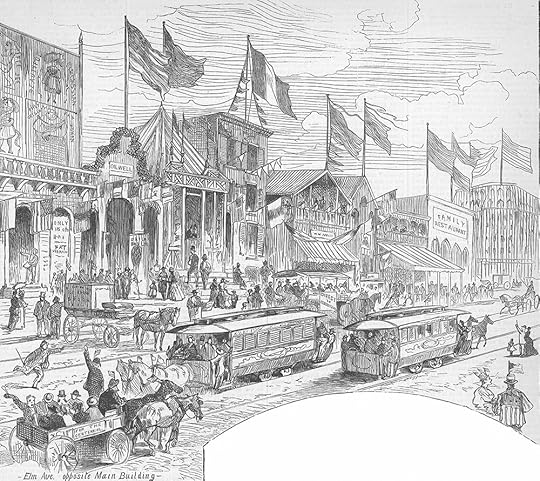

Texas Jack at the Centennial

Texas Jack made big plans for the 1876 American Centennial celebration in Philadelphia, with no way of knowing that just about everything that could go wrong would go wrong.

When Buffalo Bill Cody's son died suddenly from scarlet fever in the middle of their 1875 tour, it took the wind out of Cody's dramatic sails. He told his friend Texas Jack that he was done with acting—that he wanted to head back west, return to his former life as a scout, and spend some time with his wife and daughters. Jack understood, and wished his best friend and partner well as he planned his own exit from the constant touring of the last five years. Jack wanted to settle into a life split between quiet marital bliss with his wife at their Massachusetts farmhouse and summer trips to the wildest parts of the American West. He determined the best way to ensure his family's financial future was to make a big investment at the Centennial.

Texas Jack partnered with two other men, Erb & Lafferty, to build and open a Wild West-themed hotel on Elm Street, just across from the main entrance to the Centennial grounds at Philadelphia's Fairmount Park. In addition to supplying money for the investment, Jack sent to the hotel many of his own weapons and trappings of frontier life. Patrons could fire Texas Jack’s guns at the indoor shooting gallery before retiring to the saloon, which was well stocked with wines, lagers, ales, and whiskies. The manager of Texas Jack and Buffalo Bill's show, John M. Burke, dressed in the wide-brimmed hat and fringed leathers of his scout friends, assisted in the attraction’s operations.

Omohundro planned on staying in Philadelphia throughout the Centennial Exhibition, buying for himself and his wife a house at 614 North 44th Street, just a mile from his hotel on Elm Avenue. Morlacchi was engaged to perform both The Black Crook and The French Spy at the city’s New National Theatre for the duration of the centennial celebration.

Texas Jack was in Philadelphia as the Centennial proceedings got underway. On June 5, Texas Jack was present, “sporting a huge sombrero,” to watch a man attempt to ride his horse sixty-five miles in under three hours. At the end of June, Jack represented himself at the trial of a man who had stolen one of the cowboy’s guns from his new hotel. A notice in the Philadelphia Times about a legal proceeding in small claims court in the city details the incident:

"Thomas Murphy, a stranger in this city, was arraigned on the charge of stealing “a silver mounted barking iron” from "The Hunter's Home” a saloon in the vicinity of the Centennial Buildings. “Texas Jack” proprietor of that ranche [sic], was in attendance as the prosecutor. The trial went over, however, as the accused asked for time to send for money to retain a lawyer."

The Times also reported that “Buffalo Bill was in Philadelphia on or about the 4th of July. He has been engaged in no business, but has been interested in the support of the Indians at the Hunter's Home .” The Indians in question were Jack's future dramatic partner Donald McKay, his Warm Springs Scouts, and perhaps half a dozen Cherokee.

Texas Jack and Buffalo Bill did not spend the remainder of their summer in Philadelphia. As the date of the nation’s centennial approached, so did news about the defeat of General Custer at the hands of the Sioux and Cheyenne at Little Bighorn. Both of the scouts headed west to join the conflict, Cody to General Crook in Wyoming, and Omohundro, to General Terry in South Dakota. Working both as a scout for Terry and occasionally submitting reports on the action to the New York Herald, Jack would not return to Philadelphia until late October.On September 8, 1876, while Texas Jack rode up the Yellowstone River with General Terry, the San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin filed a story about the bustling life on Elm Avenue opposite the Centennial grounds.

"The side-shows have picked up wonderfully during the last few weeks. A great impulse has been given to business in this direction. It is 9 o’clock in the evening and Elm avenue is in full blast. On the other side of the street is the main exhibition building, dimly lit here and there, silent and deserted. So is the sidewalk fronting it. Over the way is seen a long range of wooden buildings. Their fronts are of many and incongruous styles of architecture. No two are alike; the entrances are in many cases without doors or windows; the life within is plainly seen; there are lights, red and blue and green; flaring oil lamps and calciums darting their brilliant rays up and down the street. Cross over. The sidewalk is densely thronged.

For half a mile there is a succession of saloons, beer gardens, free minstrel shows, shooting galleries, hotels, restaurants and scores of other localities and appliances for amusing and comforting humanity. There is little of the more sober and practical business of life done here; no marketing, no buying of clothes or provisions. This is a Centennial crowd. They are gathered from all quarters, and bent only on enjoying themselves. Nor is this Philadelphia. It is a city by itself—a city of the Centennial. . . . Here is the saloon of Texas Jack: The hunter's Home," with many life-size woodcuts of Texas Jack pasted on the walls. Texas Jack, rifle in hand! Texas Jack, swinging the riots. Within sits an Indian woman in a brilliant red costume adorned with beads and furs; without is a burly Indian, still more brilliant in red leggings, hunting shirt and headdress of feathers. On the curb another Indian, more glaring still in red, silently offering bead-work for sale."

Business was booming, and though Texas Jack was far away from his hotel, the investment he had sunk so much of his fortune into, he had high hopes that the success of the Hunter's Home would afford him the time and ability to stop the constant touring that had occupied so much of his life for the last five years. He wanted to spend time with his wife. He wanted to start a family.

Unfortunately for Texas Jack, while he was far away answering the call of his country, tragedy was lurking closer to home.

[To be continued.]

August 29, 2022

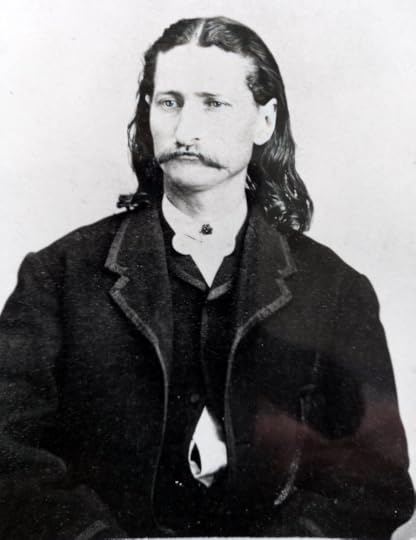

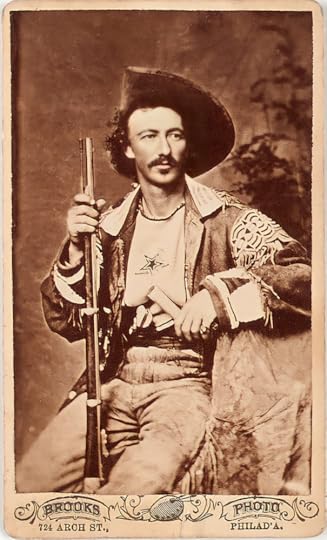

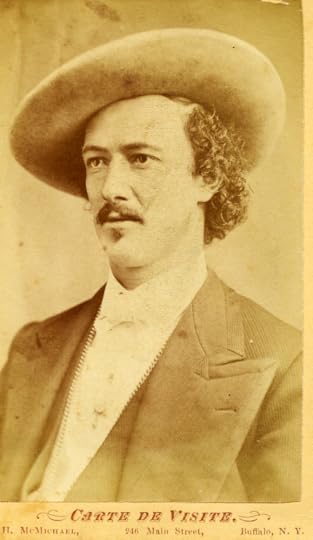

Image Enhancement CdV

While researching my book, Texas Jack: America's First Cowboy Star, I looked many times at the few existing pictures of Jack. So I was incredibly excited when Dr. John Lehman, a collector of antique photographs, sent me this previously unpublished carte de visite of Texas Jack.

This picture was most likely taken between June 12-14th, 1873 when Texas Jack, along with his friend Buffalo Bill Cody and their stage partner Ned Buntline, played three nights of shows in Buffalo, New York. By this point in the tour, leading lady Giusepinna Morlacchi had departed to fill a prior engagement, performing "Humpty Dumpty" at the Olympic Theatre in New York.

Notable in this image are Jack's gold watch chain and diamond pendant, both purchased by the scout at Tiffany's when the tour had played at Niblo's Garden in New York City during the first two weeks of April 1873. The Earl of Dunraven, who had first met Jack in his buckskin hunting gear, wrote that when he rode to Denver to meet Jack for their next hunt, "I became aware of a great coruscation, which I took to proceed from a comet or some other meteorological eccentricity, but which on approaching nearer resolved itself into the diamond shirt-studs and breast-pin shining in the snowy ‘bosom’ of my friend Texas Jack."

Many thanks to Dr. Lehman, who discovered this CdV, identified it as Texas Jack, and generously allowed its publication here.

For image enhancement, I started in Photoshop by removing the blemishes that pop up on every image that is nearly 150 years old, like the dark spot on the right side of Jack's chin and the discoloration on his left cheek.

Next, I ran the corrected image through Remini's AI, which tries to make the face a little more clear, as if this were a modern photograph.

And finally, I used MyHeritage's Deep Nostalgia tool to animate the image. Deep Nostalgia is also trying to clarify the image, and in this case I think it goes a little too far in trying to deepen the age lines on Jack's forehead and under his eyes. Jack once complained to a newspaper reporter that he was often overlooked as a guide on the plains because of his youthful appearance, reasoning that older men must have more experience. Jack told the reporter that "a man don't always carry all he knows in his wrinkles." Jack was probably 26 years old when this image was captured.

https://video.wixstatic.com/video/104311_cd685a3f7852425f8dd3552336a3b132/360p/mp4/file.mp4August 16, 2022

Will Rogers Was No Damned Good

A recent Facebook discussion on the relationship between Texas Jack Omohundro, Texas Jack Junior, and Will Rogers brought up an article by humorist H. Allen Smith about Rogers, published in the May 1, 1974, issue of Esquire Magazine. While the article starts off as a diatribe about a supposed encounter between Smith and Rogers, it functions as a long form joke, the punchline of which is particularly effective.

Will Rogers Was No Damned Good

by H. Allen Smith

AT THE RISK OF BEING SUSPENDED BY THE NECK from a cottonwood tree, I have in recent years been taking dead aim on the late Will Rogers and calling him somewhat of a fake and a fraud.

This is a hazardous undertaking because Will Rogers ranks as one of the few American saints – a religion unto himself – like Abraham Lincoln and, dropping down the scale a few notches, the Reverend Billy Graham. In the last few years there has been a sharp recrudescence of interest in the Rogers mystique, owing in large part to the barnstorming tours of actor James Whitmore, who impersonates the cow-pasture chawbacon who himself was engaged in impersonating a cracker-barrel Virgil. The public has been flocking steadily to the Whitmore one-man shows, but then, as we know, the public is capable of impersonating a ass, a idiot.

My aim in this feuilleton is to tell a single anecdote that I think is amusing, with a kicker at the end, but it is needful that I first set down a few facts and a few personal opinions about the so-called Sage of Oolagah.

Was Rogers the “profound philosopher” some people called him? Horse withers! He had a much better education than I got. The great bulk of his writing and rambling stage talk was vapid and dull and had no art in it. He came up with a slight handful of gems, out of a vast output of spoken and written prose; those renowned six chimpanzees, put to work at typewriters, could have done better, given the time.

Consider his two most famous lines, the two most often quoted, even today in the Time of Enlightenment. “All I know is what I read in the papers.” Study it a moment. Is it wise? Witty? Hilarious? And then, “I never met a man I didn’t like.” That’s the line engraved at the base of the Will Rogers monument in Claremore, Oklahoma, and I have read that it was once printed on a United States postage stamp. In a book containing Rogers’ fragmentary writings I found a more credible rendering of the celebrated line – the way Rogers himself said he spoke it: “I joked about every prominent man of my time, but I hardly ever met a man I didn’t like.” There is one hell of a heap of difference between “never” and “hardly ever.”

If he did say “I never met a man I didn’t like,” then, in my opinion, he was guilty of uttering one of the stupidest statements in all recorded history. Further than that, if he did say it that way he was speaking a large fib; he met me and he didn’t like me.

In truth he had the appearance of a rube and he sometimes put a straw in his mouth to point up the image. He cultivated that image assiduously. Gene Fowler, who knew him, told me that Rogers had a standing order with his tailor to turn out suits with built-in wrinkles, cuffs high off the floor, and baggy pants that would resist any pressing.

Rogers met me, the man he didn’t like, at the arena in Cheyenne where the annual Frontier Days rodeo is held. I was covering the 1928 event for the Denver Post. One afternoon word arrived in the press box that the great Will Rogers was wandering aimlessly around the infield and we reporters decided that it would be nice to have him sit with us so we could dress up our stories with comical Rogers commentary. I was designated a committee of one to go seek him out and invite him to come and watch the proceedings from a comfortable chair. I crossed the track and wandered around the dusty arena, and finally I found him. I introduced myself and told him how we would enjoy having him sit in the press box.

He told me to get lost. I persisted with the invitation, taking pains to avoid offending him – actually I was somewhat shivery in the knees from being in the presence of the great man and talking to him. He advised me to hit the road.

“It’s real nice over there,” I assured him, “out of the sun, and if you should want a drink we’ve got some sugar moon, and we’d all be greatly honored if you’d join us.”

“Listen, kid,” he said brusquely, “go on back to your little press box and don’t come around bothering me. I don’t wanna sit in your little press box. Now, beat it, and leave me alone.”

The uncalled-for nastiness of the Oklahoma lard head nearly knocked me down. I wanted to speak a two-word expletive to him – an expletive that later became extremely popular in the armed forces of our land. But I stood there a moment in confusion and then I turned and made my way back and told the newspaper gang what he had said. They spoke the two-word expletive, changing the pronoun from “you” to “him.”

I was just past twenty at the time, and impressionable. I have read somewhere that when Irvin S. Cobb arrived in New York and got a job as a reporter he tried to interview a man he worshiped (as I do to this day) and Mark Twain was grossly rude to him. This experience all but scarred Irvin Cobb for life – he never really got over it. I was not scarred for life by Will Rogers. I don’t think I was scarred for more than twenty minutes. But I didn’t forget his insulting manner. At the time I had some vague idea that I might write a steaming magazine article about him, a vengeful thing to do, but I am human like most people. I have been insulted and rebuffed and kicked in the teeth many times, but the thing that rankled in this instance lay in the fact that I had been scornfully shoved aside by an American saint.

So from time to time I picked up bits of information about Rogers and I compiled a dossier enumerating his sins and his prevarications. A few fragments out of the dossier are contained in the paragraphs above.

And so we arrive at a day when I had finished a writing assignment in Hollywood and I found myself with several days to loaf. I phoned two of my friends, Fred Beck, the former Pooh-Bah of the Farmers Market in Los Angeles and a columnist of note, and Will Fowler, the writing son of Gene Fowler, who was one of the truly great men ever to cross my path and who, in my own book, rates sainthood.

I told Fred and Will of my anti-Rogers schemings and said that I planned on spending the next few days probing into the guy’s Hollywood years. Will Fowler said, “You need to get in touch with Harry Brand. He knew Rogers better than anybody else in this town.” Harry Brand is a smallish man, loaded with congeniality, who was for light-years head of publicity and promotion for Twentieth Century-Fox.

“Okay,” I said, “but I’d have to make a careful approach. I know Harry and he’s a good guy, but he is capable of sentimentality. He probably believes, like everyone else, that Will Rogers ought to be canonized.”

“What you need to do,” said Fred Beck, “is get on the phone and ask him a question about Will Rogers, a question that is preposterously scandalous, a question that will shock even old Harry. Then, to tout you off of that scurrilous angle – whatever it might be – he will likely open up and give you some true stuff on Rogers, gossipy, offbeat stories that aren’t quite as shocking as the one you have given him.”

“Fine,” I said, “so let’s work up the question I can hit him with.”

The three of us tossed ideas around for a few minutes and after a while we came up with an acceptable gambit. I was to get Harry Brand on the phone, tell him I was doing research on Will Rogers, and ask him if it was true that when Rogers was working at Twentieth Century-Fox he had the dressing room next to little Shirley Temple’s. Was it true that Will Rogers had bored a hole in the wall so he could peer into Shirley Temple’s bathroom and watch the sweet little girl taking a pee?

“Great!” I said. “That ought to bring old Harry into line.”

Then and there, with Fred Beck and Will Fowler standing by, I put in the call. I got through to Harry Brand, whom I had known for a dozen years.

“Harry,” I said, “I’m working on a magazine article about Will Rogers and there’s a question I want to ask you.”

“Be happy to oblige,” said Harry. “What’s your particular angle on Will?”

“I’m going to kick the living bejesus out of him. He was a fraud from who-laid-the-chunk and I’m sick of his being set on a pedestal by the American people. On top of everything else he wasn’t funny, and furthermore ... ”

“Hold it, Allen!” Harry all but shrieked into the phone.

Let it be understood that Harry Brand has devoted most of his life to the public-relations arts, and that he is unable to think of anything or any person except in terms of good publicity. It is still his firm belief that a man is entitled to conceal his faults and emphasize his good points, even to the extent of manufacturing a fictional image of himself.

“Hold it, Allen!” he cried. “Good God Almighty, don’t be a fool! Don’t ever attack Will Rogers! You’ll be ruined for life! The entire American public will turn on you and reject you, and the newspapers will rip you to pieces. Nobody will ever buy your books again. Will Rogers is the one American you can never attack without suffering for it. You’d be ostracized.”

“Harry,” I said, “I’m not giving up on this. I’m going to put the kibosh on Rogers and his phony reputation. Every rural community in this country has its cracker-barrel philosopher, and usually his cracks about government and politicians are on a par with, or superior to, the vapidities of your old friend from Oklahoma. Let me ask you the question and see if you can answer it.” I paused, and then playfully added, “It’s an innocent enough question.”

He protested some more, because he was genuinely concerned for me. But we had been friends for a long spell and finally he said to go ahead with the question.

“Tell me this, Harry,” I said. “Is it true that Will Rogers once had the dressing room adjoining the dressing room of Shirley Temple when she was a little girl, and that Will bored a hole in the wall so he could peep through and watch Shirley Temple taking a pee? Is that true?”

There was a long silence. I could sense that the question stunned him. Then at last he gained his voice and burst forth:

“Great God, Allen! You can’t ever print that! Don’t even dream about printing it! That wasn’t Will Rogers. That was Lionel Barrymore !”

– H. Allen Smith, Esquire, May 1974

August 8, 2022

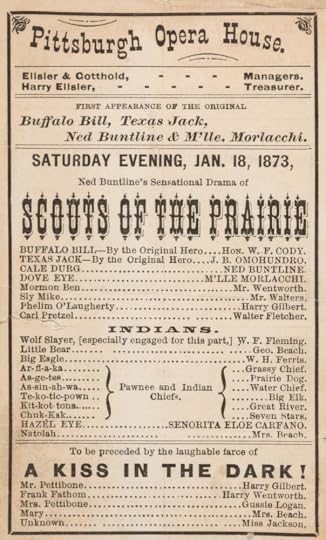

1873 Playbill

A playbill from the Scouts of the Prairie on January 18, 1873, at the Pittsburgh Opera House, starring Buffalo Bill, Texas Jack, Ned Buntline, and Morlacchi. Pittsburgh was the 8th city the tour visited, and the show on Saturday the 18th was the third and final one in the city for that tour. W. F. Fleming, who is listed as "especially engaged for [the] part" of Wolf Slayer, replaced W. P. Halpin, who was injured on stage in Cincinnati during a performance and died from his injuries.