Matthew Kerns's Blog: The Dime Library, page 15

July 29, 2023

Texas Jack Jr & The Crown Prince of Denmark

A true story of an encounter between Texas Jack Junior, an American cowboy performer in several Wild West shows, and Frederick VIII of Denmark, the Crown Prince and heir apparent.

From the New York Tribune, October 1894.

The following story is going the rounds of social circles in Copenhagen, Denmark:

The Crown Prince, who loves to take long walks, was promenading the other day along the Strandney when he came across one of the toll-keepers. After paying his tax, he began a conversation with the good man, sitting on the bench which the keeper occupied.

A few minutes later, a rider came running towards them. The Crown prince recognized him as "Texas Jack," who had ridden in several races recently. The sportsman neither knew the Crown Prince nor that he was supposed to pay a toll for the privilege of using the street. The keeper was obliged to catch the bridle of "Texas Jack's" steed, as, speaking no Danish, the latter did not understand the demands made upon him and wished to push by. "Texas Jack" was growing angry when His Royal Highness stepped forward and announced in English that users of the way had to pay 10 oere.

Upon hearing this, the long-haired rider at once put his hand in his pocket, pulled out 25 oere, and gave the money to the Crown Prince. The latter offered to return him 15 oere, but the Yankee, with a majestic wave of his whip, told the Crown Prince to keep the change as a reward for helping out in his difficulty.

On the following day, the Crown Prince went to the races. Among the competitors was "Texas Jack." A few minutes before he was to show the skill of himself and the horse, he rode up in front of the royal pavilion to make the customary obeisance to the King. But he almost dropped his reins when, looking up, he saw the man to whom he had given the fee on the preceding day occupying the place reserved for the Crown Prince. His Royal Highness greeted him, however, most heartily, and "Texas Jack" rode away smiling and to victory.

July 26, 2023

Postcards

This French postcard depicts the European dime-novel version of Texas Jack. The caption says:

[French] Texas Jack, the famous Scout of the United States.

[German] Texas Jack, the most famous Indian fighter.

European countries were fascinated with America's western frontier, and stories of the men, like Texas Jack and Buffalo Bill, that called it home. Though both men came into conflict with Native American tribes during the course of their duties as scouts, they also had complicated and complex relations with American Indians, telling their friends that the white men were the cause of most of the troubles in the West. Texas Jack was a firm friend and strong ally of the Pawnee tribe in Nebraska, and Buffalo Bill later employed many Lakota men and women in his Wild West entertainment.

The fascination for the scouts carried into a fascination with Native tribes and people. Because Texas Jack stories were cowboy stories, he was often depicted as in conflict with the Comanche tribe. This postcard features Mah-Topa, the fictional Comanche chief opposed to Texas Jack in these dime novel stories. The caption for this one says:[French] Mah-Topa, the grand Chief of the Comanche

[German] Mah-Topa, the great Comanche Chief

July 25, 2023

Ballerinas & Cowboys

Did you know that without one Italian prima ballerina, there might never have been Wild West shows like Buffalo Bill's? Without this one La Scala-trained dancer, there might never have been Westerns starring John Wayne or Clint Eastwood.

When Texas Jack Omohundro and his best friend Buffalo Bill Cody stepped off the train at Chicago’s Great Central Depot on December 12, 1872, they couldn’t know what to expect. They had been lured to the city by Ned Buntline and the promise of fame and fortune, but it seems pretty clear, historically speaking, that Buntline wasn’t certain they would come at all. A brief notice in the Chicago Tribune speaks to the lack of familiarity with these men and their names:“Among the arrivals in town yesterday were Col E. X. Judson (“Ned Runtline”; T. Cody (“Buffalo Bill”); and J.B. Omerohunder (“Texas Jack”). Colonel Judson will give a free Temperance lecture on Sunday night at Nixon’s Amphitheater. All are invited.”

In addition to misspellings for each of the names, there is no mention of the play they would stage in just three days, which makes sense considering that at that point, the theater hadn’t yet been rented and the play hadn’t yet been written. It might be strange to consider from our vantage, but Texas Jack and Buffalo Bill at that moment were no more than frontiersmen with slightly more than their share of regional notoriety, far from the stardom that would soon be theirs.

Elsewhere in the city was a celebrity whose name the Chicago papers never misspelled, Giuseppina Morlacchi. On October 11, 1867, the Chicago Evening Post had run a short piece stating that “The French steamer Periere arrived at New York recently, having made one of the quickest trips on record. The vessel is presumed to have made this trip under the inspiring presence of another quick tripper, Mlle. Morlacchi, the celebrated danseuse, who was a passenger.” The ship had actually set a record for the fastest crossing ever from Havre, France, to New York, arriving in a mere 8 days, 15 hours, and 38 minutes.

Less than half a year after her arrival in America, Morlacchi was charming theater-goers in Chicago. She made her first appearance in the Windy City in April of 1868, playing La Belle Hellene at the Crosby Opera House with Jon De Pol’s “Great European Star Ballet Troupe.” Chicago critics lavished praise on Morlacchi, though they otherwise accused the ballet of being something other than fine art.

“La Belle Helene continues to run at the Opera House…audiences begin to be a little more appreciative, though it must be confessed that their more enthusiastic demonstrations are given to the ballet, which, though very deserving--in fact, we think Morlacchi is the best premiere we have ever had in Chicago--is no more so than the acting of the burlesque. An improvement has been made by cutting the dialogues and introducing the petit can can in the midst of the third act.”

Morlacchi returned to Chicago in June of 1868 with a production of the Black Crook, the very show she initially came to the United States to compete against. The Chicago Evening Post noted that “The premiere danseuse is Mlle. Morlacchi--one of the best and most graceful danseuses in America. Morlacchi has already made a reputation, which will doubtless gain new luster in this city.” The Black Crook opened to great success. Morlacchi continued to tour, but returned to Chicago and the Black Crook in July.

Morlacchi didn’t return to Chicago for two and a half years, though Chicagoans were kept up to date when newspapers like the Evening Post and the Tribune reprinted articles on her success from newspapers in New York and Boston. In November of 1872, an announcement appeared in the Tribune to inform readers that “Nixon’s Amphitheatre will be closed this week for the purpose of putting in a heating apparatus, and will be reopened next Monday night by Morlacchi and her dramatic and ballet combination, which will produce “The French Spy” and similar dramas.”

Again, reviews were glowing. On November 26, 1872, the Chicago Evening Mail said:

“The fame of Morlacchi in her well-chosen parts is as wide as the continent, and the treat enjoyed by those who witnessed her acting in the powerful drama of the “French Spy” last evening was equal to their anticipations. Her pantomime is more intelligent than many of the spoken parts played by some of those who have come here on starring tours this season. Grace and natural gestures are seemingly parts of her very nature, and the impressions made upon those who witness them are pleasing and satisfactory. In the most difficult steps ever attempted in the ballet she is perfectly at home, executing them with the utmost ease, and bringing frequent rounds of applause from the audience.”

Unfortunately for Morlacchi, the supporting orchestra and cast at the theater were not up to snuff.

“The support accorded her in the piece was, with one or two exceptions, very deficient and unworthy of so imminent an artiste and the orchestra showed a pitiful lack of training in the music of the ballet.” The Tribune critic agreed, saying that the supporting cast and orchestra “demonstrated the extreme depth of imperfection to which a dramatic production may be brought by reason of poor material and preparation together with insufficient rehearsal. Mlle Morlacchi is a danseuse of first-class reputation…that a lady as graceful and attractive personally should fail to appear to advantage in a character which admits of such a liberal display of a pretty form and lithe and supple movements would not be for a moment maintained, but that she has been unfortunate in the linking of her name with a “dramatic and ballet troupe” wholly deficient in dramatic and saltatory merit is an equally evident and not less disagreeable fact.”

Morlacchi continued to perform the French Spy at Nixon’s until the end of November. The final advertisement for the show appears in the November 30, 1872, issue of the Chicago Tribune.

Nixon’s Amphitheatre--Clinton Street between Washington and Randolph. Morlacchi Ballet and Dramatic Combination. Afternoon and evening. “French Spy. “Dodging for a Wife.”

Compare this to a similar notice in the same paper from December 16:

Nixon’s Amphitheatre--Clinton Street between Washington and Randolph. Morlacchi Troupe. “The Scout.”

The dramatic star of “The Scouts of the Prairie; Or, Red Deviltry as It Is,” as the show was formally named when it opened on the night of December 16, 1872, in Chicago, wasn’t the scout Buffalo Bill Cody. It wasn’t the cowboy Texas Jack Omohundro. And it wasn’t the dime novelist turned playwright Ned Buntline. It was the Italian prima ballerina, the Peerless Giuseppina Morlacchi.

We know how the story goes. Texas Jack and Buffalo Bill make their stage debut that night, revealing themselves as handsome men, true heroes, and bad actors. Faced with their surprising success, Jim Nixon agrees to partner with Ned Buntline to take the show on the road, and he also takes Buffalo Bil under his wing to teach him how to be a better actor than he was on the night of the debut. Similarly, Texas Jack is assigned to work with Morlacchi. When they were formally introduced, Louisa Cody wrote in her memoirs, “Texas Jack put out his hand in a hesitating, wavering way. His usually heavy bass voice cracked and broke. There were more difficulties than ever now, for Jack had fallen in love, at sight…and never did a pupil work harder than Texas Jack from that moment!”

Morlacchi leaves the show after a few months, but she’s never far from Texas Jack’s mind. When Texas Jack and Buffalo Bill decide to tour again, this time with the famous lawman Wild Bill Hickok instead of Ned Buntline, Jack races to see Morlacchi in Rochester, New York, and they are married the following day before heading to New York together to start their lives as a married couple and as permanent costars.

Through thick and thin, up and down, East and West, they are by all accounts incredibly devoted to each other for the scant seven years they share as husband and wife before Jack’s death. When he dies, she is heartbroken. Some newspapers worry that she has gone insane, some whisper that she has already attempted suicide, and some say she has fallen under the dark influence of spiritualists to reach her beloved husband from beyond the grave. In truth, she leaves the bright lights behind for a simple life on the farm she had once shared with her husband. She takes care of her ailing sister, who dies of cancer three years after Texas Jack. Just over two years later, Giuseppina Antonia Morlacchi Omohundro passes away, also from cancer, and is buried in St. Patrick’s Cemetery in Lowell, Massachusetts, 2082 miles from where Texas Jack was buried in Leadville, Colorado.

If you wanted to take a road trip between the final resting place of the courageous cowboy Texas Jack and the beautiful ballerina Giuseppina Morlacchi, you’d start in Leadville. [24] You’d leave Evergreen Cemetery in the shadow of Mount Massive and head down the Rocky Mountains. You’d pass Lookout Mountain, where Buffalo Bill Cody was buried in 1917, and Denver, the last city Texas Jack performed in before heading to Leadville in 1880, the place he met the Earl of Dunraven before their trek into Yellowstone Park in 1874. You’d head Northeast, passing Summit Springs where Cheyenne chief Tall Bull was killed, his famous horse ending up in the possession of Texas Jack, who rode the horse to lasso buffalo. Following the Platte River to North Platte [27], where Texas Jack worked as a teacher and a bartender, and past the spot where Fort McPherson once stood on the frontier, the place where Texas Jack met Buffalo Bill and later Ned Buntline, who would write them to fame. Continuing east past the sand hills where Texas Jack saved Buffalo Bill’s life in April of 1872, where he hunted with the Grand Duke of Russia, and where he tracked buffalo with the Pawnee tribe. Halfway between Jack’s grave and Morlacchi’s, you’d be near Chicago. The place they met for the first time before the premiere of The Scouts of the Prairie at Nixon’s Amphiteatre, the birthplace of their love, and a city they returned to often. They spent the final anniversary of their first meeting together in Chicago, where they performed in theaters throughout the city from December 15th, 1879, until January 24th, 1880. They played at the National Theatre, the Lyceum, and at Mueller’s Hall, one week with Jack’s “Blood and Thunder” western drama and the next with Morlacchi’s ballet.

From the cold winter of 1879, let’s go back to the winter of 1872. Remember the reviewers who noted that despite Morlacchi’s incredible artistry and skill, the supporting cast and orchestra were wildly deficient, not up to the standards of such a phenomenal star? One of the mysteries that will never be solved is why, after all that, she agreed to be part of a show that hadn’t been written, with stars who had never acted, as part of a cast that had never rehearsed. Morlacchi could have taken her act, her show, and her talents literally anywhere, but she chose to throw her lot in with bad actors, a bad playwright, and a bad show. Why?

Sadly, we’ll never know the answer. There are no interviews with Morlacchi where she explained her reasons for sticking around in Chicago in the winter of 1872. There are no facts, which is why I couldn’t put anything in my book approaching an answer to one of my big questions. Maybe the closest we can come is that she was excited to move past dancing and pantomime into a speaking role. Indeed, the Chicago Evening Mail’s review of the very first show of the Scouts of the Prairie concludes by saying that “The honors of the evening were divided with Mlle. Morlacchi, who showed that she could do something else than dance. This is her first speaking part in English, yet she had her say with much spirit and with scarcely any perceptible foreign accent.”

But I’ll tell you what I believe. In December of 1870, Morlacchi traveled to California, where she stayed for four months, performing to full houses in San Francisco, Sacramento, and throughout the state. Returning east in April of 1871, Morlacchi’s troupe stopped in Omaha, Nebraska, to perform for a few nights. The Omaha Herald newspaper said, “She was superb. Her wonderful art and grace charmed all witnesses. Seeing her, one can well understand how, with her for a star, the California theatre was crowded night after night for weeks, and how the bluff Nevada miners brought wines and a silver brick to her carriage as she passed. She is magnificent.”

I like to imagine that somewhere in the audience that night was Texas Jack, perhaps with his friend Buffalo Bill. They’ve come to Omaha to see off some Eastern businessmen they led on a buffalo hunt for the last few weeks. The businessmen insist on buying their guides cigars and drinks, and on showing the men the beautiful, graceful, and talented dancer that has charmed them in New York, Boston, Chicago, or Philadelphia. I like to think of Texas Jack and Giuseppina Morlacchi being there together.

I like to think that at some point in that night’s performance, there is a moment where the eyes of the cowboy and those of the ballerina meet for just a moment, just long enough that when one sees the other again in the most unexpected of circumstances a year and a half later, its enough to throw caution to the wind, to sign on with a bad writer, bad actors, and a bad show. Because whether it was love at first sight or not, it was Giuseppina Morlacchi that propelled Texas Jack and Buffalo Bill to superstardom. If the diminutive Italian ballerina hadn’t agreed, for whatever reason, to star as Dove Eye alongside her future husband and his best friend, I don’t think there would be a popular culture version of the Wild West. Her stardom ignited theirs, and the rest, as they say, is history.

July 21, 2023

National Day of the Cowboy

On July 22, 2023, the United States marks the National Day of the Cowboy, a day dedicated to honoring the iconic figures who shaped the image and essence of the American cowboy. Primary among these legendary figures stands Texas Jack Omohundro, "America's First Cowboy Star." His remarkable partnership with Buffalo Bill Cody and their pioneering efforts in launching the Wild West shows have left an indelible mark on American history and culture.

Born John Baker Omohundro on July 26, 1846, in Virginia, Texas Jack would later become known as one of the first performers to romanticize and popularize the cowboy lifestyle. He earned his moniker "Texas Jack" during his time as a trail-driving Texas cowboy in the years following the Civil War. Jack also gained fame as a skilled marksman, horseman, and outdoorsman, all of which contributed to his cowboy persona.

It was in 1869 that Texas Jack Omohundro's life would intersect with that of another legendary figure, William Frederick "Buffalo Bill" Cody. The two men immediately formed a lasting friendship that would ultimately shape the American perception of the West and its cowboys. In December of 1872, they launched the Scouts of the Prairie with Ned Buntline, the first iteration of what would later be known as the Wild West shows.

The Wild West shows were a unique fusion of entertainment and realism, showcasing cowboy skills, sharpshooting, Native American performances, and even reenactments of historic battles. These shows offered a glimpse into the adventurous and rugged life of the American frontier, captivating audiences across the nation. Texas Jack Omohundro's experience as a genuine cowboy informed Buffalo Bill’s show, adding an air of authenticity to the performances, making them even more alluring to the public.

Texas Jack's contributions extended beyond the stage, as he also wrote articles about his life as a cowboy for the Spirit of the Times magazine, providing readers with a rare glimpse into the day-to-day experiences of these frontier heroes. His articles were widely read and admired, giving many Americans their first exposure to the intricacies and challenges of cowboy life. The romanticized image of the cowboy that he helped to create captured the imagination of the public, making it a symbol of adventure, freedom, and rugged individualism.

Even after Texas Jack's untimely death in 1880, his legacy continued to live on through Buffalo Bill Cody's Wild West shows. Texas Jack's articles were included in the show programs, ensuring that the memory of Cody's beloved cowboy friend remained alive in the hearts and minds of the spectators. Buffalo Bill recognized the importance of preserving the heritage of the American cowboy, and through his shows, he immortalized the cowboy culture and its connection to his best friend and first stage partner Texas Jack Omohundro.

The National Day of the Cowboy, observed annually, is a testament to the enduring influence of legendary figures like Texas Jack and Buffalo Bill, whose contributions have left an indelible impact on American culture. As we celebrate this day, let us remember and honor the original cowboy performer, Texas Jack Omohundro, whose partnership with Buffalo Bill Cody and love for the cowboy way of life continue to inspire and captivate generations of Americans. The cowboy's legacy lives on, not only in the history books but also in the spirit of adventure that still echoes across the vast landscapes of the American West.

June 30, 2023

Chattanooga Author Matthew Kerns Honored With Spur Award From Western Writers Of America

https://www.chattanoogan.com/2023/6/2...

Chattanooga author Matthew Kerns has been awarded the Spur Award by the Western Writers of America for his cover story, “Texas Jack Takes an Encore” in Wild West Magazine. Mr. Kerns' piece, published in April 2022, delves into the life of Texas Jack Omohundro, hailed as the first iconic cowboy in American history.

The Spur Award is presented annually by the Western Writers of America to honor "exceptional works that exemplify the spirit and legacy of the American West."

"Mr. Kerns' in-depth exploration of Texas Jack Omohundro's life has garnered praise for its meticulous research, engaging narrative and profound contribution to Western history," officials said.

In April, Mr. Kerns won the Western Heritage Award for the same article, the first time since 1982 that an author has won both prestigious literary awards for short nonfiction.

"Mr. Kerns' cover story sheds light on the captivating journey of Texas Jack Omohundro, who became a legendary figure through his unparalleled adventures in the untamed frontier, his depictions on stage and in print of cowboy life, and his partnership with legendary Wild West figures Buffalo Bill Cody and Wild Bill Hickok," officials said. "Through meticulous examination of historical records, Mr. Kerns unraveled the tales of Omohundro's daring exploits, painting a vivid picture of the cowboy's indomitable spirit and unyielding determination."

The Spur Award ceremony, held in Rapid City, SD last Saturday, brought together authors, industry professionals and enthusiasts to celebrate outstanding achievements in Western literature. "Mr. Kerns was presented with the Spur Award amidst a gathering of his peers, affirming the exceptional quality of his work and its significant impact on preserving the heritage of the American West," officials said.

"It is with great honor and gratitude that I accept the Spur Award from the Western Writers of America," said Mr. Kerns. "I am thankful to have the opportunity to share the remarkable story of Texas Jack Omohundro with readers across the country, and honored to be recognized by the Western Writers of America. This award serves as a testament to the enduring legacy of the American West and the power of storytelling, and to stand in the company of the remarkable authors who have been previously awarded is an incredible honor."

"Mr. Kerns is an accomplished author with a passion for uncovering forgotten tales from Western history," officials said. "His meticulous research, coupled with his ability to craft compelling narratives, has made him a rising figure in the genre. Mr. Kerns' book, Texas Jack: America’s First Cowboy Star, and this award-winning article in Wild West Magazine, exemplifies his dedication to preserving the rich heritage of the American West and ensuring that the stories of its legendary figures continue to captivate and inspire."

June 29, 2023

Texas Jack at Fort McPherson

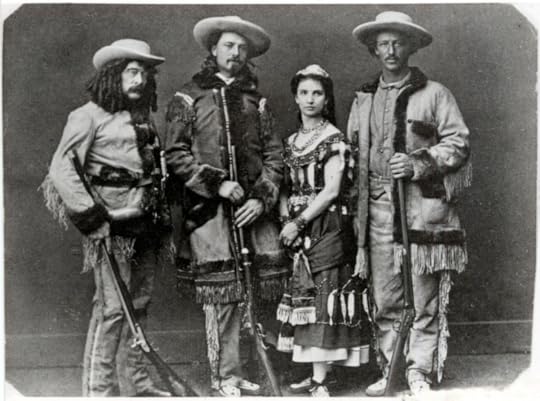

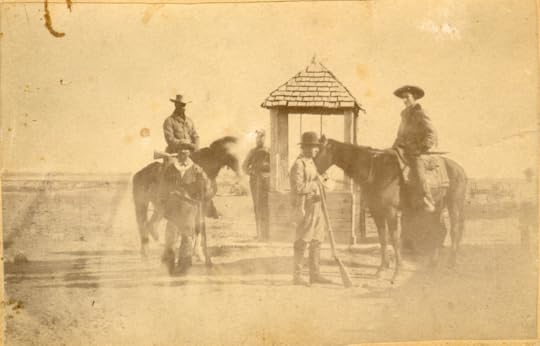

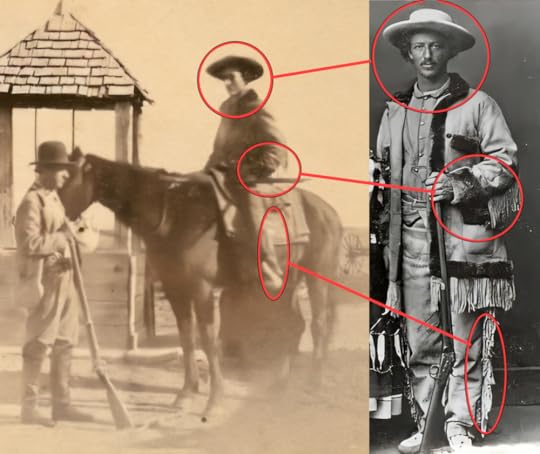

This image, taken sometime in November of 1872, is the only known image of Texas Jack with his friends the Earl of Dunraven and Doctor George Kingsley. It is also the only known image of Texas Jack, America’s first famous cowboy, on horseback. The image is part of a larger collection of images taken at Fort McPherson, Nebraska, where Texas Jack and Buffalo Bill both worked as scouts between 1869 and 1872, when they left to launch their new careers as stage stars.

The image is important because it verifies a few things I have suspected, but couldn’t verify. The first, and perhaps most interesting, is that Jack is wearing the same outfit he used on stage during the Scouts of the Prairie tour, and the same one he is wearing in the earliest extant cast picture with Buffalo Bill, Giuseppina Morlacchi, and New Buntline. This means that from the start, Omohundro and Cody were doing their best to represent themselves as close to their real-life personas as possible.

The image was preserved and digitized by, and is shared here with the permission of, the Lincoln County Historical Museum in North Platte, Nebraska, the town that Texas Jack called home, where he met Bill Cody, where he courted southern belle Ena Palmer, where he worked as a bartender at Lew Baker’s saloon when scouting work was scarce.

I love a good museum.

The West is full of great museums. Cody, Wyoming’s Center of the West, which is really five superb museums and a research library all under one roof, is one of my favorite places to experience and learn about the history and legacy of the American West. The National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City has art, artifacts, and history that explore the many facets of Western history before, during, and after the height of the golden age of the American cowboy. And the Autry Museum in Los Angeles showcases the pop culture version of the west, from silent movies to talkies on the silver screen, highlighting the ways that the story of the American West became America’s mythology.

But sometimes the real treasures aren’t just in the great museums, they’re in the really good ones. Take the Lincoln County Historical Museum in North Platte, Nebraska. Across the street from the Wild West Arena and just around the corner from Buffalo Bill’s “Scout’s Rest” Ranch, the Lincoln County Historical Museum is an unassuming building set back from the road, which in this case is North Buffalo Bill Ave.

My wife and I stopped by on the way from the Western Writers of America conference in Rapid City, South Dakota. We headed south through the Pine Ridge Reservation, stopping to pay our respects at Wounded Knee and stunned by the landscape of Nebraska’s sand hills. We walked into the museum on a warm Sunday afternoon and were greeted by museum volunteers Kathy and Doug Wentz.

I’ve visited countless museums, large and small, and seldom have I had a better experience interacting with volunteers. Kathy and Doug were quick to offer a warm greeting and pointed out a few “must-see” things in the museum. I was singularly focused on checking out the portion of the museum dedicated to the history of Fort McPherson, but found myself particularly drawn to two other sections. The first is an exhibit detailing the history of the Service Men's Canteen in the Union Pacific Railroad station at North Platte. Situated alongside the Union Pacific Railroad tracks, the North Platte Canteen stood as a beacon of refreshment and hospitality for soldiers passing through the area during their brief ten- to fifteen-minute stopovers. Throughout its operation, nearly 55,000 dedicated Nebraska women selflessly served nearly seven million soldiers, offering sustenance and care as they embarked on their journeys to fight in World War II.

The second exhibit that really blew me away was newly launched in May, and shares the stories and experiences of the Japanese immigrants that established roots in Lincoln County during and after the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05. The fact that this museum was able to pull together the contextual information, the images, and the artifacts that they’re using to tell the story of the generations of Japanese and Japanese-American men and women who have lived and worked in and around North Platte over the last 120 years is a testament to the dedication and the work that this museum and its staff and volunteers have put into showcasing the interesting history of the area.

[image error][image error]The section on Fort McPherson was great, and really shed some light on the place where Texas Jack and Buffalo Bill worked and sometimes lived while they were in frontier Nebraska. I had seen images and a drawing of the buildings at the fort before, but the images and artifacts at the museum really helped bring the place to life. The image I am sharing here was blown up and mounted as part of the exhibit, noting the time that Dunraven and Kingsley came to the area to hunt bison, elk, and deer in the Autumn of 1872. The Fort McPherson experience continued as my wife and I walked out the back door of the museum and saw the row of buildings that stretched out ahead of us.

On the right, preserved just as it had been in the days when Fort McPherson at Cottonwood Spring was bustling with soldiers and scouts alike, was the old HQ building. Walking inside, I could imagine Texas Jack and Buffalo Bill sitting at a chair and talking to General Phil Sheridan about the elk hunt they had just been on, or to Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer about where they were going to take Grand Duke Alexis to hunt buffalo. Across the path stands a period log home that once saw visitors stop for water as they crossed Nebraska on the Oregon Trail and another home that was ordered from Sears, shipped to North Platte, and assembled on site.

[image error][image error][image error][image error]A mulberry tree near the end of the lane was full of ripe berries, and birds chirped as they feasted. I was reminded of something that came up when I was researching Texas Jack and the period of his life he spent in North Platte. Dr. George Kingsley wrote in a letter home to his wife while hunting with Dunraven and Texas Jack that “Jack raves poetically as we canter along side by side, and on one of us remarking what a deal of beauty there is in the most plain prairie, he bursts out, “Ah! You should see it in the spring-time, with the antelopes feeding in one direction, the buffaloes in another, and the little birdies boo-hooing around, building their nesties, and raising hell generally!”

Listening to the birds and enjoying the scattered flowers and the ripe mulberry, I couldn’t help but think back to the Kurt Vonnegut line, “I urge you to please notice when you are happy, and exclaim or murmur or think at some point, If this isn't nice, I don't know what is.” We’re so incredibly lucky that museums like the Lincoln County Historical Museum in North Platte exist to preserve the history of a place and the people that lived there. It’s worth noting our appreciation for people like museum curator Jim Griffin and volunteers like Kathy and Doug Wentz, all helping to share the stories of those that were here before us, from dashing cowboys hunting bison with Pawnee braves to Japanese farmers desperate to start a new and better life, from the soldiers and scouts of Fort McPherson to the women and men in the North Platte Canteen.

North Platte and Lincoln County are lucky to have such a wonderful resource, and I’m pleased beyond words to find another piece of Texas Jack’s history, a picture of America’s first cowboy star on the back of his horse, ready to head out on an adventure with two of his friends, two men whose written record of those days provides such insight into Jack’s life. Enjoy this “new” picture of Texas Jack, and stop by the Lincoln County Historical Museum the next time you’re near North Platte. It’ll take you back in time, for just a little while.

June 12, 2023

From Wild West to NFL

On June 12, 1873, Buffalo Bill Cody, Texas Jack Omohundro, and Ned Buntline stopped in Buffalo, New York, with their Scouts of the Prairie tour. They had actually played in Buffalo earlier that year, back on January 27th and 28th, but as Winter had turned first to Spring and then to Summer, demand to see The Scouts again was incredibly high, and they made a return appearance.

Though the show had lost its leading star in Giuseppina Morlacchi a month earlier, by this point the names Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack were enough to fill the Academy of Music past capacity, as attested by mentions of the Scouts' return in the Buffalo Evening Post, which warned that "This evening Ned Buntline, with his favorite companions, Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack, will appear at the Academy, and we anticipate that the house will be crowded to suffocation."

The city of Buffalo retains a connection with the Wild West showmen who appeared at the Academy of Music 150 years ago in the name of its NFL team. Buffalo had several professional teams prior to World War II, such as the Buffalo All-Stars, the Buffalo Niagaras, and the Buffalo Prospects. The Buffalo Indians team ended when their league folded at the outset of the war, and after the war, the team was reconstituted as the Buffalo Bisons. A year later, in 1947, a contest was held to rename the team. James F. Dyson wrote an essay comparing the team to a band of "Buffalo Bills" and team owner James Breuil, who also owned the Frontier Oil Company, loved the connection to the American frontier legend. When the votes were tallied, the winner by popular decision was the Buffalo Bills, named after the famous scout turned showman who had passed away thirty years earlier.

[image error]Buffalo Bill's Wild West started with the Star Spangled Banner (before it was the National Anthem) and military salutes and ceremonies, the same way that the anthem and flyovers are an ingrained part of the spectacle of modern sports, including professional football.

[image error]Thirteen years after the naming of the Buffalo Bills, the NFL's first modern-era expansion team, which had been known as the Steers and the Rangers, officially changed its name to the Dallas Cowboys. Nearly 100 years after Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack popularised their version of the Wild West, their images and iconography were ingrained into the sport of professional football, which also incorporated other Wild West themes, such as calling quarterbacks "gunslingers."

The two teams first met in the 1971 season, and have since competed against each other 13 times, including the 1993 and 1994 Super Bowls, both of which were won by Dallas, who leads the series 8-5. Just like the citizens of Buffalo, New York, could go to their local theater in 1873 and see Buffalo Bill Cody and the famous cowboy Texas Jack Omohundo, people can now head to Highmark Stadium to see a matchup between two NFL teams inspired by those legends of the American West.

June 2, 2023

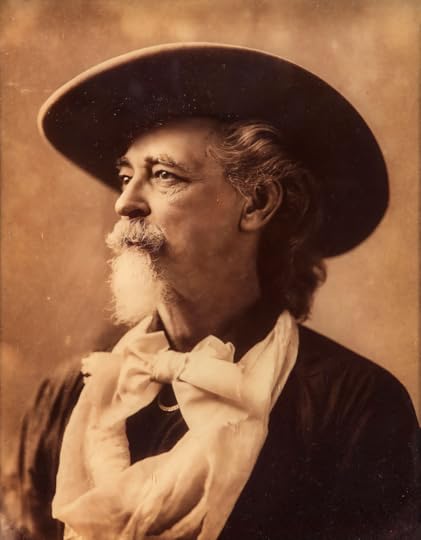

The Burial of Buffalo Bill

"Pahaska Ishtemi Washta,"

"May the long-haired man rest well."

-Sioux prayer for Buffalo Bill Cody

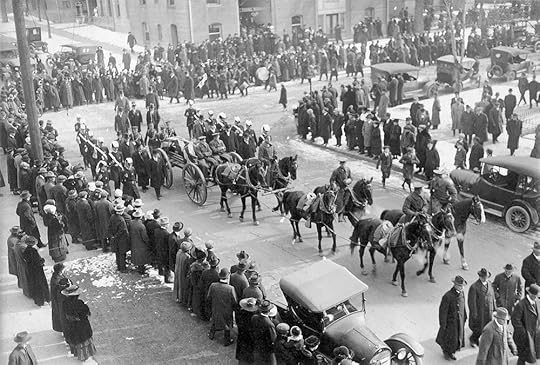

On June 3, 1917, Buffalo Bill Cody was laid to rest on Lookout Mountain, 12 miles west and 2,100 feet above Denver, Colorado. Cody passed away in January, but winter weather meant that the burial would have to wait. The road up Lookout Mountain was impassible in the snow and the ground where his casket would be laid was frozen solid. Buffalo Bill's body was laid in state in the Colorado State House where Governors, dignitaries, and citizens alike paid their respects. Then the body was quietly stored at a Denver mortuary to await summer and access to Lookout Mountain.

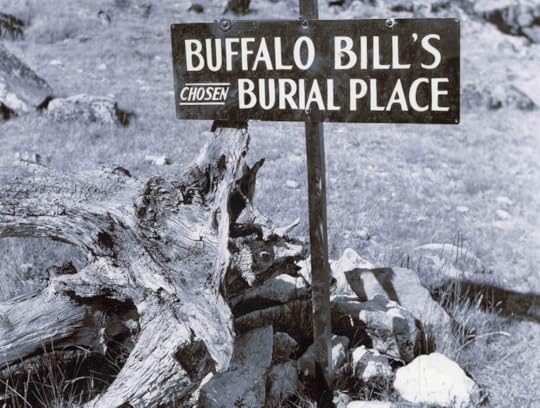

Meanwhile, citizens of Cody, Wyoming, the town that Buffalo Bill founded and named after himself, questioned the choice of the great showman's final resting place. Bill's wife, Louisa, said that he had picked the spot himself, and their daughter Irma, Bill's sisters, and many family friends like Johnny Baker corroborated her account. But there were rumors that Cody had died penniless, his once vast fortune having dwindled by overspending and mismanagement. Harry Tammen, the same circus impresario (and Denver Post owner) that had brought on the financial collapse of Buffalo Bill's Wild West now came to Louisa with the mayor of Denver and $20,000 in cash, the equivalent of nearly $520,000 today.

One story goes that Louisa left her meeting with Tammen and boarded a train for Cody, Wyoming. When the train arrived, locals gathered to pay their respects for their town's namesake. When Louisa stepped off the train, they rushed to offer their condolences. They then waited for the train's baggage door to open and the coffin to be removed. They waited, but the door was never opened. When one local man asked where Bill was, Louisa confessed "I sold him."

People crowded Denver's streets to watch the casket be carried to the top of Lookout Mountain, but again rumors circulated. The folks from Cody maintained that Cody wanted to be buried not on Lookout Mountain, but high up on Cedar Mountain where he could watch over his town. The 1906 will that Cody signed designated that exact spot, though his wife maintained that his wishes changed in the last years of his life. Some people in Cody whispered to each other that a couple of men from Wyoming had snuck down and switched the body of Buffalo Bill for an old ranch hand that bore a striking resemblance to the famous scout. They had done the work quietly and quickly, arriving back in home a few days later with Buffalo Bill's remains. No one in Denver was ever aware of the switch, the story goes, and the men were able to bury Bill on Cedar Mountain, as he had once requested.

But as the open casket was finally delivered and twenty-five thousand people gathered on Lookout Mountain looked on, it looked like Louisa Cody and the people of Denver had finally put the issue to rest. Wary that the folks from Cody might try something, the open casket was closed, sealed inside a tamper-proof case, and sealed in concrete and iron.

A few years later, Buffalo Bill's niece, Mary Jester Allen, began telling people, including those in Cody, that the city of Denver had conspired to tamper with her uncle's will, and that his final resting place overlooking Denver was not where he wanted to rest in peace. Johnny Baker, who Cody viewed as an adopted son, had opened Pahaska Teppee, a museum about Buffalo Bill's life and legacy near the grave. Now, he had Buffalo Bill's casket dug up and reburied under twenty tons of concrete.

For nearly twenty years, it seemed like the spot of Buffalo Bill Cody's final resting place was settled. But in 1948, the Wyoming Foreign Legion offered a $10,000 reward to anyone who could bring Buffalo Bill Cody's remains from Lookout Mountain to Cody, where they would be reinterred at Cedar Mountain. Legionnaires from Colorado, along with the Colorado National Guard, stationed armed men at the grave to ensure no one would be able to collect the reward money.

Today, half a million people a year stop at Buffalo Bill's grave, pausing to admire the spectacular view of the Great Plains and to remember the great showman, who at one time was one of the most famous people on the planet. But there are some who still believe that those people are at the grave of an unknown and uncelebrated ranch hand, and that Buffalo Bill is resting on Cedar Mountain in Wyoming, looking down on the city that bears his name—Cody.

Book Review: The Summer of 1876

"The Summer of 1876" by Chris Wimmer is a captivating exploration of a crucial period in American history that shaped the mythology of the Old West. Wimmer, known for his expertise in the Legends of the Old West podcast, expertly weaves together the stories of iconic figures such as Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer, Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, Wyatt Earp, Bat Masterson, Wild Bill Hickok, and Jesse James, illustrating how their paths crossed and the significance of the summer of 1876 in their lives.

One of the remarkable strengths of this book is its ability to provide readers with a comprehensive understanding of the events and their historical context. Wimmer expertly contextualizes these legendary figures' stories against the backdrop of other significant milestones of 1876, such as the inaugural baseball season of the National League, the final year of Ulysses S. Grant's Presidency, the invention of the telephone by Alexander Graham Bell, and the release of Mark Twain's timeless novel, "The Adventures of Tom Sawyer." This contextualization allows readers to grasp the interconnectedness of these events and their impact on the American West.

Wimmer's meticulous research is evident throughout the book as he paints a vivid picture of the summer of 1876 and the characters who defined it. Wimmer's narrative style is engaging and accessible, making it easy for readers to immerse themselves in the stories and feel connected to the larger historical landscape. He presents a balanced portrayal of both outlaws and lawmen, humanizing these larger-than-life figures and delving into the motivations and complexities that shaped their actions.

"The Summer of 1876" not only explores the lives of these legendary figures but also explores the broader historical context surrounding them. The 100th-anniversary party celebrating the signing of the Declaration of Independence serves as a powerful backdrop for the events unfolding in the West, highlighting the significance of this particular summer in American history.

In summary, Chris Wimmer's "The Summer of 1876" is an engaging exploration of the events, outlaws, lawmen, and legends that defined the American West. It provides readers with a deep understanding of the interconnectedness of these stories and their historical context. Wimmer's engaging narrative style and attention to detail make this book a must-read for anyone interested in understanding the mythology and history of the Old West.

June 1, 2023

A Letter From Buffalo Bill to Ned Buntline

Reprinted in Street & Smith's New York Weekly, July 22, 1872:

Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack.Letters from these real heroes of the present day inform us that the first named has just departed on a perilous trip into the far North-West, to recover property stolen by the Indians, while the latter is engaged in a new enterprise, which will add to his fame and bring him prominently before the public in a short time. Meantime, “Ned Buntline’”’ is far away, but busy on his new story of“Texas Jack, the Hero of the Loup.”

FORT MCPHERSON, June 4th, 1872.

Dear Colonel:—Before leaving on my trip among the Indians, I pen you a few lines to let you know myself and family are well. I leave to-morrow for a two months' trip. I am going from here across the country to the Missouri River among those Northern Indians, for the purpose of getting back some stolen horses. The Indians have stolen so many horses from the railroad and taken them so far north that troops have never followed them to their stronghold, where they feel secure with their stolen property, but now we are going to follow them to their own country and get the horses.

Texas Jack is not going on this trip, he starts tomorrow to catch wild buffalo for a gentleman here from Niagara Falls. They are going to take some full-grown buffalo there, and some Indians, and have a genuine buffalo hunt. Jack will make you a visit while he is East.

Your true friend, W. F. Cody.