Alex Boyd's Blog, page 9

April 7, 2013

Updated: The Lonely Offices

Recent updates to The Lonely Offices include poetry by  Pino Coluccio (The Incredible Shrinking Man), Sandra Kasturi (Come Late to the Love of Birds), and John Donlan (For the Baysville Public School Reunion).

Pino Coluccio (The Incredible Shrinking Man), Sandra Kasturi (Come Late to the Love of Birds), and John Donlan (For the Baysville Public School Reunion).

Also, in our first posted review Lori A. May takes a look at The Best Canadian Poetry in English 2012.

March 3, 2013

Time Of My Life

Canadian poet Chris Banks has some very thoughtful things to say on the subject of time in poetry, and in particular quotes a few of my poems (“Someday the Men with Hats Will Go” happens to be one of my favourites from the new book). Thanks, Chris, for the careful consideration of the book.

February 27, 2013

Northern Poetry Review 2006 – 2013

For various reasons, I’m bringing Northern Poetry Review to a close. I’ve enjoyed producing the site, but began it nearly seven years ago with the assistance of web-maintenence man Jean Raco, who did a remarkable job and has been very professional. Blogs were not as attractive in 2006, and I wanted something more impressive. But Jean has also moved on to other work that’s keeping him much busier, even as I now have greater restrictions on my time, and finances.

But I still feel poetry suffers from shrinking amounts of attention, perhaps more than ever, so I’d like to introduce The Lonely Offices which takes its name from one of my favourite poems, Those Winter Sundays by Robert Hayden. It’s also a somewhat playful reference to the solitude that comes with the act of writing, and the ongoing challenge of finding new readers. In any case, it’s a fresh start, and a project I can access much more easily. I look forward to posting poems more often than we saw on Northern Poetry Review, as well as other material. The new site is already updated with a Carmelo Militano interview of George Amabile, and I hope to post a poem soon. Have a look, and please do spread the word.

I’m open to speaking to somebody new about taking over Northern Poetry Review, but for now I’ll simply keep the site online for further reference. And my thanks, once again, to Jean for all your help with it. If I miss anything about it the most, it will be the little trees designed for the main page. Dani Couture was the friend willing to help me launch it, and I don’t think I’d have done it alone. Finally, if NPR managed to bring some attention to deserving poets, it’s thanks to the many people who took the time to write a review, do an interview, or contribute a poem. Many of the same, regular, wonderful contributors have already expressed an interest in the new site, so I’ll see you at the new place. The movers have been told to wrap all the breakables very carefully.

February 21, 2013

Dustin O’Halloran: Piano Solo, Opus 23

January 29, 2013

Northern Poetry Review: Emily McGiffin, James Arthur

Northern Poetry Review is updated with a review of Between Dusk and Night by Emily McGiffin, review by Lori A. May. And James Arthur provides a poem from his new collection Charms Against Lightning.

January 20, 2013

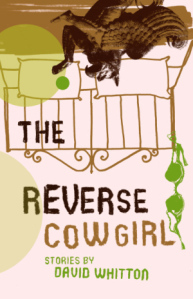

One Question Interview: David Whitton

David Whitton is the author of the story collection The Reverse Cowgirl (Freehand Books, 2011). You can find him online at www.dwhitton.com.

Hitchcock said drama was life with all the dull bits left out, while director Jim Jarmusch has made films about the time between events. Of course, a director isn’t a short story writer, but I wondered if any particular fascination motivated your stories? They seem to be about bland characters in extraordinary situations, and involve an awareness of alternatives. One character is aware of a phantom life based on different decisions, and “could almost reach through the electrons and touch it.”

Remember the story of the love-sick astronaut? The one who allegedly drove hundreds of miles, allegedly wearing a diaper, to kidnap her ex-lover’s new girlfriend? This was a few years ago. A married mother of however many kids who had engaged in a two-year affair with a fellow astronaut? It’s an amazing story.  Her lover had broken off the affair and had started seeing someone else. So Lisa Nowak, an astronaut, a married mother of however many, and an American hero, packed up her car with rubber tubing, pepper spray, a wig, a hammer drill, and a bunch of other stuff, and headed out to Orlando, Florida, to do whatever she planned to do to her ex-lover’s new girlfriend. Wearing a diaper, allegedly.

Her lover had broken off the affair and had started seeing someone else. So Lisa Nowak, an astronaut, a married mother of however many, and an American hero, packed up her car with rubber tubing, pepper spray, a wig, a hammer drill, and a bunch of other stuff, and headed out to Orlando, Florida, to do whatever she planned to do to her ex-lover’s new girlfriend. Wearing a diaper, allegedly.

It’s this kind of story, as awful and tragic as it might be to the parties involved, that fills me full of wonder. The world out there.

The famous pop singer caught wanking in a public restroom. The suburban mom who runs a high-price escort service in her spare time.

I imagine if you asked Lisa Nowak today what she was thinking, she’d say, “Good God, I have no idea. I don’t know what possessed me.” Because that’s what people say, isn’t it? “That wasn’t me. Who was that person?” “What the hell was I thinking?” And this question, for me, is at the heart of my fiction. We might, by piecing together the evidence, have a shot at understanding some small part of someone else, but we have no chance whatsoever of understanding ourselves. Vanity, greed, desire: they pump out a fog of self-deception that will forever keep us from knowing our real motivations.

The quiet Amish man who traffics heroin. The nerdy Ph.D. student who shoots up a movie theatre. What were they thinking? Surely they didn’t want their lives to amount to this. But something inside them made it happen. Character is destiny, the Greek guy said. Extraordinary situations are borne of exotic interior lives.

Why am I a construction worker instead of an aesthetician? What is it about me or my world that made me a security guard instead of a wealthy socialite? The characters in my book ask these (unnerving, torturous) questions. Don’t you? Doesn’t everyone? And wonder when and how all your hard work and planning went wrong?

The shakiness of identity. The randomness of destiny. How little it takes for us to believe our own lies. Most of my stories touch on this stuff. My story “Raspberries”: there’s a line in there about a newly married couple—“a mystery to each other, a mystery to ourselves”—that sums up this particular line of inquiry. Our past selves are fictional constructs, written and rewritten to suit our present needs; our present selves are rockets whizzing headlong through the subatomic particles, without much capacity for reflection or analysis; and our future selves are just a theory based on current models. What a wild situation.

January 2, 2013

The Rotary Dial

The Rotary Dial is a new,  monthly magazine of “formalist-ish” poetry, looking for work that “rhymes and scans but isn’t too versey.” Edited by Alexandra Oliver with support on the project from Pino Coluccio.

monthly magazine of “formalist-ish” poetry, looking for work that “rhymes and scans but isn’t too versey.” Edited by Alexandra Oliver with support on the project from Pino Coluccio.

Sounds like an interesting niche, and it will be in a downloadable, accessible format. You can also like them on Facebook to stay updated.

December 11, 2012

Year in Review: 2012

My second book of poems, The Least Important Man was published in the spring, and the good folks at Biblioasis have been amazing. The launch at the Dora Keogh was a great turnout, and they helped get me out of town for a few readings, most memorably Words Worth Books in Waterloo, with Al Moritz who very graciously offered me a lift home. Our conversation about poetry and life was so interesting we missed an exit somewhere and didn’t immediately notice we were sailing past empty fields in the wrong direction.

I did a handful of readings in Toronto to support the book, and stumbled into remarkably warm nights at Livewords and Pivot, and finally made it to one of the informal poetry weekends organized by Ross Leckie at the University of New Brunswick, and despite rain, rain and rain it was an excellent group of appreciative, down-to-earth and talented folks. A final note on my book: it has seen two reviews, so I do have my fingers crossed for another review, and particularly one that will have the space to discuss some of the themes and ideas.

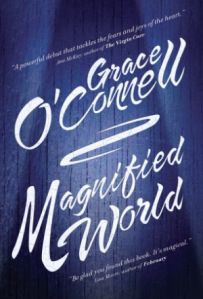

Favourite novels of the year: I admired The Grapes of Wrath for its honest, emotional intelligence (and wrote something about it for the National Post), and The Sea, The Sea by Iris Murdoch and The Sportswriter (Richard Ford) had utterly convincing narrators who couldn’t help but leave an impression. I waited too long to read Of Human Bondage (Somerset Maugham) which was remarkable, and flawless. I also really enjoyed Magnified World by Grace O’Connell for being an engaging read and unabashedly about Toronto, which is the sort of thing we need to see if Toronto will ever be perceived the way we think of a city like London. I dedicated the summer to reading novelists I’d never picked up (which I’d recommend, as a fairly satisfying thing to do) though I still have a long list of authors I’d like to read. Oh, and The Assistant (Bernard Malamud) was a careful, quiet and beautifully written book I discovered on a useful list of great novels compiled by Time magazine.

Favourite genre books: The Big Sleep (Chandler) and Red Harvest (Hammett) and both absurdly enjoyable. Later in the year I moved on to Neuromancer (Gibson) who borrows the basic idea of the hard-boiled detective, but like someone putting utterly different baubles on a Christmas tree, writes the narration as though it comes from a techno-junkie poet from the future. I didn’t enjoy the Gibson novel as much, mainly because I think the description sometimes gets away from him and leaves the reader nowhere in particular. It’s an exercise in style, unless the reader steps back to consider the overall setting and the idea that eventually our creations might come to seem more real to us than anything else. Personally, the day people prefer a hologram to a tree is the day I need to check out of this world. When Twitter suggests we make our profiles beautiful I want to say no, Twitter, beautiful is when you turn off your computer and step outside. The Forever War is highly recommended, for being an engaging read loaded with interesting ideas.

Non-fiction: Intolerable, by my friend and colleague Kamal Al-Solaylee is an important and well-written book. Pulphead (essays by John Jeremiah Sullivan) is an enjoyable, articulate voice to spend some time around, and The Boy in the Moon (Ian Brown) has something essential and very human to communicate. And while A Journal of the Plague Year is technically fiction (Defoe was five when the plague hit) it certainly reads like a memoir and it’s morbidly fascinating, disturbing and heartbreaking. The simple idea that people came home to kiss their children and pass along the plague is something that will likely haunt me forever.

Poetry books: I bought many and have completely finished few. I’m not entirely sure what’s happening with me at the moment, but lately my interest has been elsewhere in terms of my reading. My daughter brings a smile to my face every day, but I’m perhaps too tired to frequently sit down and try and make associative leaps in my reading. My One Question Interview with Chris Banks about Winter Cranes certainly suggests how much I appreciated his book, and I read First Comes Love by Pino Coluccio cover to cover, finding poems that reminded me of Larkin. Finishing Groundwork (Amanda Jernigan) and Spinning Side Kick (Anita Lahey) I thought they were underrated poets, much like Coluccio. Other than that, I dipped into poetry books here, and there. A concentrated effort to read more poetry in 2013 might change things. I suspect it will be quite a while before I have enough poems for another book, and I’m attempting to write a novel these days.

December 8, 2012

Northern Poetry Review: Sharon McCartney, Mary di Michele

New to Northern Poetry Review: Fredericton  poet Sharon McCartney shares her poem from Best Canadian Poetry 2012. It’s also a poem that will appear in new new collection Hard Ass, set to be released in the spring from Palimpsest Press.

poet Sharon McCartney shares her poem from Best Canadian Poetry 2012. It’s also a poem that will appear in new new collection Hard Ass, set to be released in the spring from Palimpsest Press.

Also, Alessandro Porco reviews The Flower of Youth: Pier Paolo Pasolini Poems, by Mary Di Michele (ECW Press).

Coming in January: Lori A. May reviews Between Dusk and Night by Emily McGiffin, new from Brick Books.

November 15, 2012

One Question Interview: Grace O’Connell

Grace O’Connell is a writer, editor and teacher based in Toronto, with work published widely in places such as The Walrus, The Globe and Mail and the Journey Prize Stories. Her acclaimed first novel, recently published by Random House, is Magnified World.

Toronto is almost another character in your compelling and carefully written novel. Was it a natural fit, with the city lending itself to this process, and what special qualities does Toronto own?

The book actually started out, in its earliest draft, in an unnamed, Toronto-like city a la The Edible Woman. I was struggling with certain scenes and I realised, as I wrote more, that the story really wanted to be in Toronto, properly and identifiably in Toronto. Once I made that switch, the narrative flowed much more naturally, and I was able to get deeper into my character’s mind at the same time. So it was more than natural – it was essential to the book’s development.

Since I was writing in first person, any sort of artificially withheld information only served to block Maggie’s voice. There are so many things Maggie doesn’t know, and couldn’t know, in the narrative, that I didn’t want to withhold anything she did know. And since the city is so important to her, so emotionally charged, I had to be specific about it, the way she is. Maggie is a list-maker – when she thinks of the city, she thinks of it exhaustively, counting up what she loves about it; it’s the same way she thinks of her mother.

In terms of special qualities, I’m not sure I’ve lived in enough other places to answer this in a comparative sense (that is, to say what Toronto has in contrast to other cities). But the city itself has a sort of contradictory feeling of frenetic peacefulness that I really like. There are thousands of unique narratives in every city block – you could zoom in and tell countless stories – but you can still take a quiet walk at night and feel like the city is calm. I think that combination of noise and silence worked well for Maggie’s story. And the quality of neighbourhoods, which are like characters themselves; each little neighbourhood in Toronto has such individual, identifiable qualities, which I love as both a resident and a writer.

The bizarre part for me was trying to extract myself from Maggie and her view of the city after I was finished with the book. For instance, whenever I go over the Queen Street viaduct and see that “This River I Step In is Not the River I Stand In” sign, I feel like I’m in the scene where Maggie learns her mother is dead. It’s like a Pavlovian association, but from a life I never actually lived. A life I made up. It’s kind of spooky – I guess writing does weird things to a person sometimes.