Alex Boyd's Blog, page 13

April 17, 2011

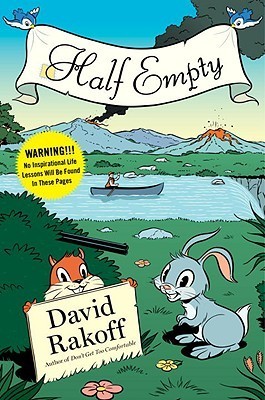

David Rakoff: Half Empty

Years ago I caught sight of a set of Curious George parodies, along the lines of Curious George and the Electric Fence. I only really glanced at it, because in all honesty I don't enjoy that kind of humour. Childhood is ideally a brief window of innocence where the idea that it's a decent world – and maybe even one we can improve with effort – is nurtured, and there are decades later on to find out life isn't loaded with happy endings, and that random misfortune strikes.  Contrary to feeling misled, I've always found it useful to be able to tap into a period of time I believed wholeheartedly in that more innocent view of the world, and I've never been able to appreciate seeing the trappings of childhood dressed in crude humour and cynicism.

Contrary to feeling misled, I've always found it useful to be able to tap into a period of time I believed wholeheartedly in that more innocent view of the world, and I've never been able to appreciate seeing the trappings of childhood dressed in crude humour and cynicism.

It was with a little trepidation I examined the cover of the new David Rakoff book of essays, Half Empty. A rifle emerging from the bushes is about to take out a cute bunny, and a bright yellow bubble assures us "No inspirational life lessons will be found in these pages!" Well, fine. I understand marketing is a requirement. But Rakoff is more than cynical and witty. In an age of Twitter wisdom ("The one worth crying over will never make you cry!") it's refreshing to luxuriate in a well-written essay, and Rakoff is articulate and thoughtful, with elements of a certain reserve and a certain moral framework. While he's certainly witty and cautious (more than cynical), his voice gives frequent nods to the kind of world we could have, if it were infused with heavier doses of thoughtfulness. In the essay on his battle with cancer, he notes "It is the duty of society to take care of its individuals, plain and simple." And here it might be fair to say we also see an acknowledgement of the Canada we used to know – the one that believed quite firmly in picking people up when they fall, and the one we knew before politics became about as subtle as a hard-knuckle fistfight.

Here is Rakoff on the cliché of the artist: "Let us pause herewith for a moment of honesty about that old chestnut about art and artists being immune to the petty concerns of morality, or the need to be kind, or fair, or in fact anything other than obliteratingly self-involved. It has always seemed little more than a rationalization for goatish, flesh-pressing painters, writers, and musicians to skip out on checks, borrow but not return things, sire but not take care of children, and mostly to cheat on, mooch off of, or sock long-suffering wives and girlfriends." And later, "the only thing that makes one an artist is making art. And that requires the precise opposite of hanging out; a deeply lonely and unglamorous task of tolerating oneself long enough to push something out." What might seem conservative at first glance isn't a disdain for artists, just a disdain for treating each other without consideration. He could drop unnecessary flourishes ("herewith"), but occasional minor distractions aside, Rakoff is among the best Canadian essay writers. Individual essay titles like "The Satisfying Crunch of Dreams Underfoot," are as good as novel titles by other writers. He's perhaps even more interesting for being a Canadian transplanted to the States while retaining certain Canadian values that may or may not be on their way to extinction. Highly recommended.

April 8, 2011

One Question Interview: Cornelia Hoogland

Cornelia Hoogland has published five poetry collections, has been short-listed for the CBC Literary Awards on multiple occasions, and is currently an Associate Professor at the University of Western Ontario. Her most recent poetry collection is Woods Wolf Girl, described as a "sensuous Canadian retelling" of Little Red Riding Hood.

What inspired a Canadian retelling of Little Red Riding Hood?

I attribute my deep and abiding love of the fairy tale Red Riding Hood to my childhood on densely wooded Vancouver Island, B.C. I've come to understand the fairy tale as quintessentially Canadian, and the girl herself, a Canadian heroine. The landscape of Woods Wolf Girl is the wet west coast. The rain forest. Here's a sample:

A girl walks into the woods and

trees! Of course trees –

she recognizes the plot. A way through

viridian cedar, Douglas-fir,

Hooker's middle green.

Follow the earth

smell round

the next corner:

rotting logs,

saplings, licorice fern.

Kelp-green branches,

a long velvet dress,

shawls in orange, sienna, and indigo,

shawls of olive witches' beard.

Woods Wolf Girl not only leads into the woods, it returns the woods and mountains to the wild. Canada's wolves are an increasingly unique phenomenon in a world we've stripped of wildness. Research for this book led me to Haida Gwaii and to Bella Bella on B.C.'s west coast, as well as to the Rocky Mts. in Banff, Alberta, to study wolves and record their voices. Along the way I met people with powerful commitments to aboriginal understandings of land, place, and their connections to people through story.

In Woods Wolf Girl, the character of the Mother (who rarely gets more than a finger-wag in telling of the fairy tale) is an immigrant who is deeply shocked by the natural world that threatens to invade her house. The experiences of Canadian immigrants – moving through the land, making sense of it, and inscribing themselves upon it – are inherently part of our Canadian narrative. I write:

Tentacle vines twist

into the house, grab

at me, howling, arching their backs and spitting.

Saplings swarm my limbs, skinny little things

no higher than my chest, slap

their nervous tails.

And they call; beseechingly, they call.

Woods Wolf Girl is my interpretation of the fairy tale, Little Red Riding Hood – which is arguably the world's most popular, and certainly its most retold, tale. Canadian viewers will recognize the heroine in the conventions and codes of western, horror, picture and comic book. The tale has been adapted to theatre, cartoons, poster, advertisements, musicals, films, animated films, video games, television, and the Internet. Bookstores such as Chapters sells more than one hundred different editions, and the tale is told on every continent, in every major language.

In formal and informal storytelling sessions in a number of countries (such as Brazil, Cuba, Indonesia and Greece), I have observed that Red Riding Hood is one of the few stories that most people know, in rough outline at least. The "O Grandmother, what big teeth you have" chorus comes quickly to mind, as does the red cape, and meeting the wolf in the woods. People have a personal stake in the story; most know at least three of its plot events – and here's what I love – each person remembers it in his or her own way.

April 3, 2011

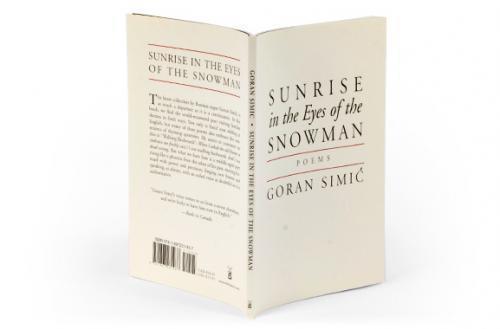

One Question Interview: Goran Simic

Goran Simic was born in Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1952 and emigrated to Canada in 1996. His internationally published work includes stories, plays, essays and poems. Since coming to Canada, his published books include Immigrant Blues and From Sarajevo with Sorrow (poems) as well as Yesterday's People, and Looking for Tito (stories). His new book of poems is Sunrise in the Eyes of the Snowman.

The acknowledgements for your latest book of poems say you wrote it in English to gauge how comfortable you were in the language and how much you sound like yourself. What are your thoughts on that?

Since I arrived to Canada my major problem was not to adapt to the new country but to make myself functional as the author of many books published in small languages like Serbo-Croatian, Finnish, Danish, Flemish. After surviving Bosnian war I came from the country of Yugoslavia that ceased to exist, together with the official Serbo-Croatian language as well I was born with. I started with the history of "nowhere man" — to use the definition from my friend writer Aleksandar Hemon.  I felt displaced and dislanguaged and fragile coming to Canada armed with five years old kid knowledge of English. The major support to get myself visible came first from my wife Amela and later my girlfriends until they became ex leaving me abandoned in my writing feeling like Mexican cactus replaced to Nunavut. I faced drama of losing myself as the author and was questioning if I was wrong listening to Susan Sontag advice to chose Canada as the best place to set up my new nest.

I felt displaced and dislanguaged and fragile coming to Canada armed with five years old kid knowledge of English. The major support to get myself visible came first from my wife Amela and later my girlfriends until they became ex leaving me abandoned in my writing feeling like Mexican cactus replaced to Nunavut. I faced drama of losing myself as the author and was questioning if I was wrong listening to Susan Sontag advice to chose Canada as the best place to set up my new nest.

Following thought that says "if you jump in the river don't admit you are not swimming," I started learning English by listening and reading and in that period English Dictionary became my lover and Toronto Reference Library became my homeland. Also I guess my friends became sick and tired of me asking them to do translate some of my work. Friend and poet Fraser Sutherland was a great help.

It took me five years to feel I can express myself in the language I adopted, and another seven years to feel comfortable to write in English. The major problem was to find that invisible bridge between my thoughts and language, between me as a fragile baby and me as the author, refusing to be already mentioned cactus in the snow. I started dreaming in English — even my worst nightmare was that my progress in English will collide with forgetting my mother tongue. Writing in English I faced the fact that I lost lot of English nuances, but I believe that if you have strong idea you don't have to search for the form because form will find you in any language. Only good poems are translatable in any language.

My journey into new language territory started with the pain, continued with curiosity and now I am in the phase of loving it. My poetry book "Sunrise in the eyes of the Snowman," that I worked on for four years, is my first try to see where did I get. Or simply, to see am I cactus or the snow.

March 31, 2011

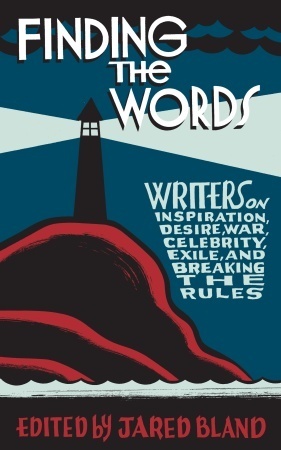

Finding the Words

There's a tidy pile of reasons to pick up Finding the Words, a new anthology of essays edited by Jared Bland. It's a PEN Canada fundraising project, firstly. As noted in the concise, engaging introduction, the writers donated original work, illustrator Seth donated his cover design, and McClelland & Stewart and Random House contributed production and shipping costs.

The content is as engaging as it is accessible, like walking away from a number of interesting conversations. Favourites included Heather O'Neill relating family history in a piece so full of fascinating detail it reads like a good short story. Stacey May Fowles has a remarkably lucid piece on writer anxiety. Madeleine Thien sent me looking for my highlighter with this line, which now makes me wish people were more interested to find out the details of our current election: "Movements and ideologies do not spring from the air; we are building them all the time, persuading ourselves of their value, following their bright promises to utopia." David Chariandy makes use of a Theodor Adorno quote: "It is part of morality not to be at home in one's home."

Subtitled Writers on Inspiration, Desire, War, Celebrity, Exile and Breaking the Rules, it might sound to some readers as though it's a book for writers. Really, it's a book for everyone. It may not be the best climate for it, but here's hoping more publishers take chances on thoughtful collections like this one. As the saying goes, they're an antidote to all sorts of things we didn't even know we were suffering from.

March 20, 2011

Selected Stories: Maupassant

I'm really enjoying the stories of Guy de Maupassant, who apparently disliked the Eiffel tower so much he'd have lunch under it, to be able to look away from it. His stories mix cynicism, amusement and sharp observation and there's some remarkable, heartbreakingly good stuff here. From the Penguin selected stories, here's a paragraph from "Two Friends," about two men who decide to go fishing again despite the fact that Paris is under siege:

"They started a friendly argument, discussing the great political problems with the sweet reasonableness of peaceful men of limited intelligence, and agreeing on one point: that men would never be free. And all the time Mont-Valerien went on thundering, destroying French houses with its shells, pulverizing human lives, crushing bodies, putting an end to countless dreams, countless expectations, countless hopes of happiness, and inflicting wounds that would never heal on the hearts of girls, wives and mothers in other lands."

Ladies and Gentlemen, Guy de Maupassant

I'm really enjoying the stories of Guy de Maupassant, who apparently disliked the Eiffel tower so much he'd have lunch under it, to be able to look away from it. His stories mix cynicism, amusement and sharp observation and there's some remarkable, heartbreakingly good stuff here. From the Penguin selected stories, here's a paragraph from "Two Friends," about two men who decide to go fishing again despite the fact that Paris is under siege:

"They started a friendly argument, discussing the great political problems with the sweet reasonableness of peaceful men of limited intelligence, and agreeing on one point: that men would never be free. And all the time Mont-Valerien went on thundering, destroying French houses with its shells, pulverizing human lives, crushing bodies, putting an end to countless dreams, countless expectations, countless hopes of happiness, and inflicting wounds that would never heal on the hearts of girls, wives and mothers in other lands."

March 18, 2011

@alexboydwriter

Just a note to let folks know I'm trying out Twitter. I'm not sure I'll be wildly active, but seems like a good way to share interesting news and updates.

So far, Roger Ebert (@ebertchicago) has had some very insightful things to say that aren't necessarily about film.

March 13, 2011

And Also Sharks

Looking forward to the new book from Jessica Westhead, a collection of stories called And Also Sharks. There's an impressive trailer now online:

March 3, 2011

One Question Interview: Matthew J. Trafford

Matthew J. Trafford has published fiction widely in magazines and anthologies, including I.V. Lounge Nights, and Darwin's Bastards: Astounding Tales from Tomorrow. He won the Far Horizons award for Short Fiction, received an honourable mention at the National Magazine Awards, and has twice been shortlisted for the CBC Literary Prize. His first collection of stories is The Divinity Gene.

Your title story in the collection — The Divinity Gene — has Christ cloned, and it struck me that are enough ideas for at least a few more stories. It also seemed to be about old world versus new world values, and that's reflected in your own changing styles for different sections of the story. Is that fair to say, and what inspired the story?

In the story, Maciej's father is born in 1882, and the "Poplopedia" post is last updated in 2029, meaning on some level the story spans 147 years. The amount of technological change experienced in the last century is far greater than in any other single century previous. So I think technological change is as much a part of what's reflected in the different voices and styles of the story's three sections as values are, but of course value systems deeply impact how we create and use technology. The more religious characters in the story do tend to be from the old world, while the new world characters are more secular and focused on technology, pleasure, and profit. But I wasn't trying to imply one was better than the other, and the styles also have to do with what information the reader needs and how best to get it across. For example, talking about the fate of thousands of Jesus clones (Jesi) required an omniscient voice and a quick, informative, style – an encyclopedia entry seemed perfect for that, and an online one made sense given the fact that section of the story is set slightly in the future. Jordan's section had to be first person so we could understand his internal workings, his motivations and his guilt. The third section tells the story of why Maciej would want to do such a thing as clone Jesus — but since we already know the horrible results of what happens, the tone of this section – which also deals his with childhood and schooling — is the most innocent and almost nostalgic (though ultimately misguided).

sections as values are, but of course value systems deeply impact how we create and use technology. The more religious characters in the story do tend to be from the old world, while the new world characters are more secular and focused on technology, pleasure, and profit. But I wasn't trying to imply one was better than the other, and the styles also have to do with what information the reader needs and how best to get it across. For example, talking about the fate of thousands of Jesus clones (Jesi) required an omniscient voice and a quick, informative, style – an encyclopedia entry seemed perfect for that, and an online one made sense given the fact that section of the story is set slightly in the future. Jordan's section had to be first person so we could understand his internal workings, his motivations and his guilt. The third section tells the story of why Maciej would want to do such a thing as clone Jesus — but since we already know the horrible results of what happens, the tone of this section – which also deals his with childhood and schooling — is the most innocent and almost nostalgic (though ultimately misguided).

"The Divinity Gene" may contain many disparate ideas and styles, but the core inspiration for it was truly the Eucharistic miracles discussed in the middle section. I was thinking about these rare miracles, in which, supposedly, the bread and wine at a Catholic mass literally and physically change to flesh and blood, and which have been verified to some extent by science. I was struck how if you take spirituality and faith out of the equation, these events would still present intriguing human mysteries — if there's no God miraculously changing these substances, then there must be a human conspiracy of extreme proportion underway, to covertly get real human blood and real human heart tissue into these churches. I started thinking about whose heart had been sliced to perpetuate this hoax, how it could have been done — and then, swung back again to the possibility of these miracles being real, the tissue actually being that of the historical Christ. I'm not sure what I believe about these miracles at the end of the day, but that idea of having Jesus's flesh, his very DNA, is what led me to wonder what might happen if we tried to clone Jesus Christ. Subsequent to the story's publication, I've found out that there are several other works of fiction that examine the possibility of cloning Christ –but usually the genetic source material is taken from the Shroud of Turin — mine is the only story I know of that deals with Eucharistic miracles.

Another inspiration for the story was a conversation I remembered from my Catholic high school in which one of my fellow students asked our religion teacher why God didn't just perform miracles all the time, in order to make contemporary people believe in Him. My teacher answered that witnessing miracles did not necessarily lead to faith — to prove this, he cited all the doubters in the Bible, people who knew and lived with Jesus and saw miracles firsthand but still did not believe. This idea was new to me, and stayed with me, and eventually expressed itself in the story — both in Jordan Shaw's assertion that seeing the host bleed (a Eucharistic miracle) was nothing so out of the ordinary that it warranted a conversion of conscience, heart, or religious faith, and also in Maciej's misguided motivation for cloning Christ in the first place, wanting contemporary people to be able to witness Christ's miracles and thereby come to faith. The words of my teacher in high school — that seeing isn't believing, that faith is a decision, that witnessing miracles today would not automatically make believers of us all — is what led me to think about how we might desecrate and exploit a contemporary Jesus — especially if He came to us through cloning and commercially controlled science.

The third inspiration — I can't seem to get away from threes with this story, a number which has its own religious associations — came from pop culture rather than religion: the film American Beauty, which I love. There's a scene in that movie in which a teenage boy steals a key from his father in order to open a locked hutch and show his neighbour-girlfriend one of his father's most prized possessions: a set of original official dinnerware from the Nazi Party, in mint condition. This moment haunted me. When I was working on the middle section of the story, trying to figure out how to get Jesus's DNA from inside a church into the hands of geneticist Dr. Maciej Wawrzyniec, I knew that I wanted a wealthy photographer of holy artifacts to steal them. But another devout religious character wouldn't really add anything to the story, and just didn't feel right. Then I remembered the Nazi plate in American Beauty, and that's when Jordan Shaw and his "Cabinet of Human Atrocities" was born — a person who is fascinated with human evil, and who collects and reveres unholy relics. It seemed to work, and Jordan has become one of the most memorable and living characters in both the story and the entire book.

I hope this answers your question.

February 19, 2011

NPR update: all-interview issue

Northern Poetry Review celebrates a first all-interview issue with four new interviews:

Natasha Nuhanovic interviewed by Lori A. May, Richard Greene interviewed by Carmelo Militano, Ian Burgham interviewed by Catherine Graham, Robin McGrath interviewed by Jacob Bachinger.

Many thanks to all the contributors.