Alex Boyd's Blog, page 12

October 25, 2011

A Dry Run for the End of the World: The Day of the Triffids

It's an odd thing for a post-apocalyptic novel to be reassuring, if only because it goes far enough to illustrate that the end of the world also means the beginning of a new one. I've written about my[image error] admiration for John Wyndham before, and how a series of B-movie titles gets in the way of readers appreciating a novelist who combines interesting ideas with the kind of sensitivity and far-sightedness we expect in a good poet.

I recently watched a 2009, 3-hour BBC mini-series of The Day of the Triffids, and wanted to revisit the book after. I'd forgotten how many ideas are in the book. Wyndham has written a terrifying novel, for demonstrating how disturbingly easy it is for humanity to be bumped out of the driver's seat, so to speak. Here, it's the result of two events only a few decades apart: carnivorous, stinging triffid plants are created, and then a freak cosmic event watched by millions leaves most people blind, with rare exceptions.

He starts with this idea: if you could see, would you work to help the many hundreds of blind people all around you, or join whatever sighted people you could find? One is morally correct, the other far more likely to prove successful and save your skin. From there, he explores how habit can interfere with our ability to adapt to a world-changing crisis, what kind of system we should live in post-disaster, and even how to motivate children when a glorious former golden age is gone, possibly forever.

The mini-series touches on the first of these ideas, a simplified version of the second, and none of the rest. At the same time, a character who appeared in about fifteen pages of the novel is elevated to the status of major villain — just for the sake of having one, it seems — and goes around shooting his own henchmen, which leaves the audience wondering why anyone would follow him at all. There's a new, more dramatic ending, and even the triffids get slightly different treatment. They're crafty in the novel, able to sense movement and wait for people outside doors, but in the mini-series they're given stingers that can smash a car window, so that unsettling suspense is replaced with frenetic action.

In short, the mini-series manages to be impressive entertainment, but only a diluted version of the book, despite a long running time. It leaves me hoping the series resulted in a few more people reading the novel — given the number of complex problems plaguing the world today, a British, slightly dated dry run for the end of the world is not only fascinating, it might actually be vaguely helpful to people, even if only in terms of their expectations, and having some slight level of familiarity with immense changes.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

September 6, 2011

One Question Interview: Salvatore Ala

Salvatore Ala has published poems widely in journals and anthologies, as well as five broadsides of his work. His first book, Clay of the Maker, was published by Mosaic Press in 1998. With Biblioasis Books, he has published Straight Razor and Other Poems, and more recently Lost Luggage.

While your poems in Lost Luggage certainly have intellectual ideas in them, they're ground in some very organic imagery: fish, dragonflies, almonds, rain barrels, pine, fog and snow, crabapple wine. Considering your title, is it fair to say your book is at least partly about how we've left something important behind in modern, everyday life?

When I look back at poems I didn't include in the final manuscript, this sense of having "left something important behind in modern, everyday life" is even more apparent. I was trying to strike a metaphorical balance, but as you know these ruminations are subtle. The past is very much part of the present in this collection, though I would add that some poems which do not appear on the surface to be part of the motif of having "left something important behind…" are in fact also about lost origins. Working from the etymology of words is for me a way of seeing what's not there, and is very often the source of the imagery in a poem. "Ala," "Church Demolition," and "Roman Coins" are very much poems about lost or uncertain origins. I was also able to question value and judge hypocrisy with the strongest evidence being in the roots of the words themselves.

motif of having "left something important behind…" are in fact also about lost origins. Working from the etymology of words is for me a way of seeing what's not there, and is very often the source of the imagery in a poem. "Ala," "Church Demolition," and "Roman Coins" are very much poems about lost or uncertain origins. I was also able to question value and judge hypocrisy with the strongest evidence being in the roots of the words themselves.

The organic imagery you mention is somewhat easier to explain. It is in part how I grew up, close to the organic and close to someone like my grandfather who even living in an urban center, secured himself a tract of land so that he could live like he did in "the old country." Sometimes you would not have imagined that a city existed outside the little oasis he cultivated. Another reason for the organic nature of my imagery is quite simply that it's a quality I have always admired in other poets. I remember in my early university years I was fascinated by everything new, new trends in literature and art, and in life. It wasn't until I studied Martin Heidegger's famous book Poetry, Language, Thought, in particular his brilliant essay "The Origin of the Work of Art," that I began to investigate origins in my own life. It was also at this time that I met the French philosopher Michel Henry, whose book La Barbarie (1987) had a profound affect on me, as did his idea that aesthetic experience returns us to the inner life of objects as lived experience.

So I would say yes to your question. Much of Lost Luggage deals with "how we've left something important behind in modern, everyday life." The heroism of reason and science can't go unchecked. It seems clear that the hubris of technology has swept us up into a society of people pacified by gadgetry and indifferent to reality. I suppose poetry is a small reminder of that other life whose origins are being steadily eroded.

September 2, 2011

Harvey

A brief but potent graphic novel, Harvey feels like an authentic Canadian story that's also universal enough for anyone to appreciate. Written by Hervé Bouchard and illustrated by Janice Nadeau, it's recommended for young adults (ten or over) or anyone interested in a well-crafted and poetic graphic novel.

The story is simple enough: Harvey and his brother return home from playing to find their father has passed away of heart failure. The failure of the boys to completely understand – and the failure of adults to completely explain, over and over – rings true, even as the illustrations by Nadeau capture a world that's slightly surreal to a particular child: walls sometimes go on forever, and patterns sometimes leap off dresses. Unfortunately, the only review currently on Amazon suggests American children may not be able to relate, but that's simply rubbish. There's nothing exclusively Canadian about the death of a parent, and an American child need only be told to anticipate a few French-Canadian names to completely understand the book. The feel of small-town Quebec is certainly strong here, but isn't critical to a child interested in appreciating the book.

In another touch that feels authentic, Harvey escapes into the world of American hero Scott Carey, central character in The Incredible Shrinking Man, a film that would've been a popular success at the time (now a somewhat obscure, but still a well made and entertaining film). Winner of Governer General's Literary Awards for both text and illustration.

August 28, 2011

The Layton Test

I found many moments to appreciate in the funeral celebration for Jack Layton. It isn't often Canada is united in voicing its appreciation for someone. The only note of discord in the ceremony happened when Stephen Lewis gave his moving eulogy for Layton, including the idea that his last letter was, "at its heart, a manifesto for social democracy," creating a brief, awkward moment when most people cheered and a few prominent Conservatives sat silently.

While I certainly feel saddened at the loss, what's interesting about Layton passing away is the message it instinctively sends home to people: has your life been a worthy one? Will people mourn your passing like this, and feel you left the world better than you found it? Giving yourself the Layton test isn't a new idea, but it's a potent reminder to a distracted, materialistic culture that puts the economy ahead of all things, to such an extent that corporate tax cuts are justified as stimulus to the economy. Layton simply talked about direct government action to lift all Canadians out of poverty, and other promises that suggested a compassionate manager rather than a leader that would impose a personal vision on the country. People recognized Layton was out to make life better for all Canadians.

I wasn't cheering for Jack Layton during the recent federal election. I think if Canadians had looked beyond a somewhat unpolished performance from Michael Ignatieff – who was not a career politician – they'd have seen a message of hope and fairness. I watched Ignatieff speeches on YouTube that were nearly half an hour, and was impressed with his sincerity. But however many barbecues and rallies he attended across the nation, the English language televised debates count for a great deal, and Layton delivered several knockout punches, at one point even eliciting a testy reply from Ignatieff that made me cringe at how it looked. And it looked particularly bad next to the unflappable Stephen Harper. I'm not saying I disliked Layton, but if I was caught up in any one political story during the election, it was a Liberal leader swimming quite strongly against the current of unfair labelling and getting nowhere. It solidified my opinion that no party should be able to campaign before an election begins, as the Conservatives did.

At the time I watched the English language debates, I also subscribed to an idea given to me by every poll and election thus far: only the Liberals can replace a Conservative government. Didn't Jack Layton know he's going to come third? Shouldn't he have spent the debate highlighting the Conservative failings? Needless to say, he declined to do so, and gave his party a historic result that may very well have been an NDP minority government if not for several other factors, including almost constant polls insisting on Conservative victory. Now that he's succeeded in changing the deeply held belief the NDP always place third, Canadians suddenly see that we actually could've had him as our prime minister, and we realize this the same year we lose him forever.

But back to the one awkward moment at the ceremony: I hope the Conservatives attending the state funeral for Layton didn't feel like they were the enemy, as I doubt Layton would have wanted it that way. Conservatives love their country too, and competing visions of Canada have always been at the heart of Canadian politics, or any politics. Having said that, I do think the country (and indeed, the world) is at a crossroads, and the Conservative view begins to seem like an increasingly misguided one. If the death of Jack Layton helps illustrate anything, it's that no politician will be cherished and remembered for a legacy of corporate tax cuts, or standing in the way of clean energy.

I think Jack Layton knew there was a new energy economy on the way, and the sooner we begin real investments in solar and wind power (Germany already requires that new houses are built with solar power) the better. Clean energy is critical to slowing climate change, already beginning to have devastating results. History will show that some leaders stood in favour of progress, while others will only be remembered for delaying it. The Conservatives could learn a lot from this, and they certainly have time to think about it, with every opposition party in disarray. Maybe they'll give thought to leaving the kind of legacy that inspires chalked messages of thanks and grief. The life and career of Jack Layton will inspire many to take up his cause, but if people across the country of different political stripes are giving themselves the Layton test, that's also a remarkable final gift.

August 8, 2011

NPR update: Gabe Foreman interview, Modern Canadian Poets reviewed, and more

Northern Poetry Review is updated  with an interview with Gabe Foreman — his new book of poems from Coach House Books is A Complete Encyclopedia of Different Types of People. Also from Coach House, I've reviewed The Brave Never Write Poetry, a reprint of a 1985 title by Daniel Jones.

with an interview with Gabe Foreman — his new book of poems from Coach House Books is A Complete Encyclopedia of Different Types of People. Also from Coach House, I've reviewed The Brave Never Write Poetry, a reprint of a 1985 title by Daniel Jones.

Ingrid Ruthig reviews Modern Canadian Poets, edited by Evan Jones and Todd Swift, and our "Best of Blog," series begins with I Am Corrupted, by Seth Abramson. Finally, poems by Nick Thran from Earworm, new from Nightwood Editions.

July 17, 2011

One Question Interview: Carolyn Black

Carolyn Black's stories have appeared in literary journals across Canada. "Serial Love" was published in the prestigious Journey Prize Anthology, and "At World's End, Falling Off" won Honourable Mention at the National Magazine Awards. Her recently published collection of stories is called The Odious Child.

These are carefully crafted, modern and relevant stories, but they also feel somewhat like modern fables — characters are sometimes identified by role rather than by name, and drastic, symbolic things sometimes happen. What appeals or is useful about this style of fiction?

It was a way to escape a method of storytelling where Character was the primary element. For instance, when I named characters, they grew bloated in my imagination and seemed to weigh down my mind. As soon as I took away names, the characters shrank and my mind became active and playful. I think it was because I knew the characters would be easier to throw if they were tiny. I feel some hostility towards characters, so do like to hurl them away from me with force, but my arms are weak, spending all the time that they do merely typing. Being unnamed and tiny, as most of my characters are, they are quite easy to chuck around in a more equitable relationship with other elements of fiction. The characters cannot come clamouring for my attention just as I am working out something I want to say about Language or Form. They don't have enough power to demand a flashback scene about the significant events from their past that account for their possession of certain subtle and turbulent emotions, which will now require fifty paragraphs to delineate. Shut up, you tiny creatures, I can say instead, while I hurl them away from me. I don't empathize with them one bit, these squalling beings. I'm not a monster. It is just that they exist as formal elements, not real human beings. I do empathize with real human beings; I don't empathize with formal elements. And I hope any readers of my writing might experience the same distancing or refocusing of attention away from Character. Many of the stories are about alienation, with characters disassociated from the community or the self, and I want the readers to experience this feeling in their own relationships to the characters.

characters, so do like to hurl them away from me with force, but my arms are weak, spending all the time that they do merely typing. Being unnamed and tiny, as most of my characters are, they are quite easy to chuck around in a more equitable relationship with other elements of fiction. The characters cannot come clamouring for my attention just as I am working out something I want to say about Language or Form. They don't have enough power to demand a flashback scene about the significant events from their past that account for their possession of certain subtle and turbulent emotions, which will now require fifty paragraphs to delineate. Shut up, you tiny creatures, I can say instead, while I hurl them away from me. I don't empathize with them one bit, these squalling beings. I'm not a monster. It is just that they exist as formal elements, not real human beings. I do empathize with real human beings; I don't empathize with formal elements. And I hope any readers of my writing might experience the same distancing or refocusing of attention away from Character. Many of the stories are about alienation, with characters disassociated from the community or the self, and I want the readers to experience this feeling in their own relationships to the characters.

June 28, 2011

Northern Poetry Review call for submissions: Best of Blog

Since Northern Poetry Review  started five years ago, we've seen an explosion in personal poetry blogs and sites. I think it's fair there are many thoughtful and dedicated people online, and there's certainly a wealth of excellent writing that deserves more attention.

started five years ago, we've seen an explosion in personal poetry blogs and sites. I think it's fair there are many thoughtful and dedicated people online, and there's certainly a wealth of excellent writing that deserves more attention.

Perhaps we can help. Send us your best piece on any subject related to poetry and we'll be happy to consider posting it with a link to your blog, either in a special update or one or two at a time. No strict word limit, but somewhere between one thousand and four thousand words would be ideal. Send to northernreview [at] gmail.com. Thanks for NPR editor Alessandro Porco for the idea.

May 25, 2011

G. K. Chesterton: On Lying in Bed and Other Essays

It's quite a remarkable essayist that can take an obscure subject and generate four pages of approachable wisdom out of thin air, without relating a single personal anecdote. Of course, nothing emerges from thin air, and a writer like G.K. Chesterton considers subjects he must have been thinking about for quite some time. But that doesn't change how impressive his writing is for remaining fresh, insightful, curious and joyful.

At over five hundred pages, On Lying In Bed and Other Essays (Alberto Manguel, editor) is a hefty selection of work, but it's well worth the trip, so far. Several essays in a row take the time to refute our mixed up priorities, and then detail the virtues of the overlooked: "Gold is certainly a less fascinating element than silver. And even silver is to the spirit which retains its childhood less fascinating then lead. Lead is a truly epic substance … in colour it is the most delicate tint of dimmed silver … it is at once robust and malleable, it bends and it resists; we have the same feeling towards a stiff layer of lead that we have towards destiny." Only lead could have been used for the bands and framework of stained glass, Chesterton suggests, so that the "gigantic jewels of the church," were blocked by "heavier boundaries" as if outlined by a "very big and broad lead pencil."

All this might seem self-evident on reading it, but I think it's an excellent writer that turns over and explores a lot of unsaid, vaguely instinctive ideas to see if they ultimately make sense, and why we might believe in them. Chesterton even goes on to consider if lead is the working class substance, or the one that restricts the working class, for standing "stiff and still in churches," or being suddenly "spat out in shots," in the form of bullets.

Even if there are occasional flaws in his thinking, his very approach gently and consistently encourages original thinking. Certainly, he doesn't limit himself, and appears capable of fascination with anything, commenting in "A Defense of Bores," that "the blame, if there be blame, is with us for being bored." Meditations like these should be seen as valuable by anyone who believes our society should have a degree of flexibility, and an ability to reexamine.

May 17, 2011

NPR update: Samuel Andreyev interview, Linda Besner poems, and more

Northern Poetry Review is updated with poems by Linda Besner from her new book The Id Kid and Di Brandt is reviewed by Michael Greenstein. Alessandro Porco interviews Samuel Andreyev and also finds time to report on some of the happenings at BookThug, more specifically Stephen Cain and Mark Goldstein.

In addition, Jacob Mcarthur Mooney reviews four chapbooks of poems from Cactus Press: Instructions for Pen and Ink by Edward Nixon, Wolf Hunter by Darren Bifford, I Don't Think I Need to Tell You by Sarah Teitel, and Sanatorium Songs Marc di Saverio (his chapbook cover pictured here). Many thanks to all the contributors and participants.

On a related note, NPR turned five in April. I'd like to take the opportunity to put out a renewed call for submissions. A lot has changed in five years, including an increase in the number of poet and writer blogs, but I think NPR has something different to offer the conversation. It's easy enough to do an in-depth interview through email by making note of five or six questions as you read a book, and we welcome articles and reviews of all kinds, as always. Contact me at northernreview [at] gmail.com.

I've been glad to see the announcement of NewPoetry.ca, where George Murray takes the idea that a site should cover a diversity of styles a step further by formalizing it with a set of associate editors from various fields. It's a good idea. I'll be following along, and you should check it out too.

May 12, 2011

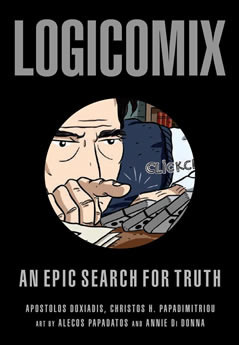

Logicomix: An Epic Search for Truth

Bertrand Russell titles like Unpopular Essays and The Conquest of Happiness helped shape the way I write essays and remain among my favourite books. One of the brightest minds of his generation — and certainly among the more privileged — Russell purposely turned away from obscure academic work at one point in his life, embracing writing that would be accessible to more people.

A graphic novel about his earlier years, Logicomix attempts quite a bit. While I can hardly blame it for ignoring his later work (the book states it's about his "early life," and somewhat more generally "the quest for the foundations of mathematics, whose most intense phase lasted from the last decades of the 19th century to the eruption of the Second World War." While I can appreciate the attempt to give dramatic weight to intellectual struggle, the stage of his life where he took 362 pages to prove that 1 + 1 = 2 certainly proves to be a difficult one to dramatize. Adding thunder and lightning to dialogue like "A new set of axioms!" doesn't, I'm afraid, come across as anything more than clumsy and heavy-handed. The books frequently visits his personal life, from an unhappy childhood to several marriages, but the reader is yanked out of the narrative at least as frequently because the writers and illustrators felt the need to repeatedly insert their own commentary as a form of narrative framework, in addition to another narrative framework that has Russell telling the story of his life in a lecture hall, to make a point to a crowd that objects to the war.

the 19th century to the eruption of the Second World War." While I can appreciate the attempt to give dramatic weight to intellectual struggle, the stage of his life where he took 362 pages to prove that 1 + 1 = 2 certainly proves to be a difficult one to dramatize. Adding thunder and lightning to dialogue like "A new set of axioms!" doesn't, I'm afraid, come across as anything more than clumsy and heavy-handed. The books frequently visits his personal life, from an unhappy childhood to several marriages, but the reader is yanked out of the narrative at least as frequently because the writers and illustrators felt the need to repeatedly insert their own commentary as a form of narrative framework, in addition to another narrative framework that has Russell telling the story of his life in a lecture hall, to make a point to a crowd that objects to the war.

There's much to admire in a graphic novel that takes on such mature and intelligent themes, and the illustrations are certainly unpretentious and down to earth. I just can't help but feel the book goes in a few too many directions. And an opportunity is missed — at least in terms of creating an introduction to his work — when there's little or no mention of his very different career later in life. Our time with Russell has an ending of sorts, and then the final chapter is hijacked by the writers and illustrators as they march off to see a production of Oresteia — suitably dramatic and epic, but I did find myself wishing they'd instead found room to add a little more to the remarkably complicated and fascinating life they've tried to present.