Mark Piesing's Blog, page 4

November 11, 2024

I have just recorded my first History Rage Podcast!

Not many history podcasts’ briefing notes begin with the instruction to “Get Angry!” but History Rage does!

My History Rage episode will be out in January for subscribers and April for everyone else!

October 4, 2024

My latest book review for The Spectator: Giles Milton retells the story of the Grand Alliance as a cinematic thriller

Please read my review of Giles Milton’s latest bestseller, The Stalin Affair, in full below, or the original by clicking this link.

It appeared in print in the September 2024 edition of The Spectator World magazine.

On June 22, 1941, the German army invaded the Soviet Union. Over the next four months, the Wehrmacht blasted through the Soviet defenses, taking millions prisoner and destroying thousands of tanks. By early December, German scouts were purportedly within site of the Kremlin. Even though the Wehrmacht was forced back from the gates of Moscow by the Red Army, the renewed German offensive in spring 1942 threatened to deliver the coup de grâce to the Soviet Union. That it didn’t was due to an unlikely alliance between British prime minister Winston Churchill, US president Franklin D. Roosevelt and Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin.

In his new book The Stalin Affair: The Impossible Alliance That Won the War, historian Giles Milton tells the story of how Churchill and Roosevelt were able to forge close relationships with Stalin, a man they loathed and whose regime they detested, in order to defeat Adolf Hitler. But the book’s real interest lies in its depiction of individuals such as the wealthy and good-looking American businessman Averell Harriman, his vivacious daughter Kathleen and maverick bisexual British ambassador Archie Kerr. They made the Grand Alliance work by giving frank advice to their bosses, usually behind the scenes, opening doors that would otherwise be closed and getting the job done.

In the hands of a less skilled writer, The Stalin Affair could easily have been rather dull. But Milton turns this true story of high politics into an addictive, gossipy, alcohol-fueled, action-packed thriller that sweeps the reader effortlessly through the ups — and downs — of the alliance, from its forging in June 1941, to the Yalta Conference in February 1945 and its collapse into acrimony and the beginning of the Cold War. There’s a good reason why an earlier title for the book was Vodka with Stalin.

Milton adeptly uses a previously unseen collection of hundreds of personal letters written by Kathy Harriman, shared with him by her son, to make readers feel that they too can hear the Panzers at the gates of Moscow, or imagine they are knocking back vodka shots with foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov.

Unlike the appropriately claustrophobic atmosphere of Milton’s previous work, Checkmate in Berlin: The First Battle of the Cold War, his new book (in effect a prequel) is cinematic in its approach. It sweeps the reader from the German invasion of the USSR to lunches at Chequers, the British prime minister’s country retreat, and from banquets in the Nicholas II throne room in the Kremlin to the depths of the Katyn forest, where more than 20,000 Polish officers were executed by the Soviet secret police in 1940. Darkness is never far away in The Stalin Affair.

Milton’s skill as a storyteller is such that he can combine epic story arcs like these with smaller-scale, revealing anecdotes. When the invasion begins, he crosscuts to the leaders as they hear of the event: Marshal Zhukov tells a bleary-eyed Stalin over the phone that the Germans have invaded, and then shouts at him, “Do you understand?” when the dictator is silent in disbelief. Churchill awakes at Chequers to the news. His quick decision to commit Britain to come to the aid of the Soviet Union is broadcast over the radio later that day, despite the opposition of his advisors. “Any man or state who fights against Nazism will have our aid,” he growls. In Washington, Roosevelt is more cautious: huddled with his advisors, he issues no statement and gives no emergency press conference. Pearl Harbor is less than six months away.

Milton perfectly captures Stalin’s growing despair at the destruction of his army, tracking the way it turns into depression and paralysis. “Lenin founded our state… and we fucked it up,” says Stalin. Later he tells his ministers, “Everything is lost… I give up.”

On that cliffhanger, the author introduces us to Averell and Kathy Harriman. In spring 1941, the American millionaire had been sent as an envoy to Britain to expedite Roosevelt’s Lend-Lease program, the policy that allowed the US to give weapons and supplies to Britain and Allied nations free of charge on the basis that the aid was vital for the defense of the United States. For Harriman it was “the job of a lifetime” because he was able to deal directly with Churchill, answered only to Roosevelt and was given carte blanche to get the job done.

Harriman’s experience of his first air raid over London led him to his highly risky affair with Pamela Churchill, the prime minister’s daughter-in-law, who, untroubled by their twenty-eight-year age gap, “was determined to spend the night with him.” As an observer wryly notes, “a big bombing raid is a very good way to get into bed with somebody.

The American businessman’s “unusually close relationship” with his spirited twenty-something daughter Kathy meant that she soon followed him to the UK, where as a journalist she wrote popular eyewitness accounts of the plucky British during the Blitz. Averell rented a house for his lover and his daughter to share. Kathy described her father’s lover as “a bitch… who only looks out for herself,” but subsequently became very good friends with her, although the affair was something they never discussed.

Milton delves skillfully into the minutiae of the period, bringing his protagonists alive. He makes the reader want to dally, enjoy and chew over every detail of the Harrimans’ lives, at the same time wanting to know the answer to a question: how is Stalin going to survive?

He is portrayed here as an almost pathetic figure. For days after the invasion Stalin wasn’t seen in public. Diplomats thought he might have fled to Turkey or China. “But the truth was much worse,” according to Milton. The man who ordered the deaths of over a million men and women in his Great Purge hadn’t washed or changed his clothes for days. He wandered his dacha in a daze. It was only on June 30, when his ministers formed the State Defense Committee in his absence, that he was shaken out of his stupor. Soon afterward he gave his first radio broadcast since 1938.

But the Red Army’s defeats continued, and Arctic convoys carrying urgently needed British and American aid were struggling to reach the Soviet Union. Averell Harriman traveled to Moscow to see Stalin. His inspired solution to the problem is one of the most fascinating of the many little-known stories in the book, and perhaps the most important. Harriman, who had begun as a railroad magnate, came up with a plan for the United States to take over the running of the Trans-Iranian Railway linking the Persian Gulf with the Caspian Sea at the Russian border, which the British had been running like a “suburban branch line.”

They then applied American engineering brilliance, railroad know-how and muscle — in the form of 28,000 US troops — to some of the “roughest, toughest, railroading” in the world, which transported, at the peak of its operation, the equivalent in weight of around 50,000 jeeps to the Soviet Union every week. The result was that American jeeps and trucks became the savior of the Red Army.

It may be true that great forces shape history, and that it was inevitable that the economic muscle of the British Empire, the Soviet Union and the United States would crush Nazi Germany in the end. But it is also true that sometimes those forces need a little help.

The author captures this perfectly in his account of Churchill’s visit to Stalin in August 1942. The prime minister knew he had to forge a friendship with the Soviet dictator that would be the equal of his bond with President Roosevelt, but Stalin reacted furiously to the news that the opening of a second front was going to be delayed and accused the British of cowardice. Later, drinking heavily, Churchill referred to Stalin as “an ignorant peasant” and described the Russians as “not human beings at all” in a room he knew to be bugged. The gap between imperialist aristocrat and revolutionary peasant was, perhaps, too wide to bridge.

Churchill’s anger only increased when Stalin sneered in an after-dinner toast about “the gross stupidities in concept and execution” of the World War One military debacle at Gallipoli — which Stalin knew had been the responsibility of Churchill. Now it was the prime minister’s turn to rage. As Milton highlights, it fell to Archie Kerr to persuade Churchill to stay in Moscow. Summoning up his courage, Kerr told Churchill that he “had had great faith in him [Churchill], and he had disappointed me…” As his anger at Kerr’s insolence subsided, Churchill asked, “So, you think this all my fault? …Well, what do you want me to do about it?”

The book can be deliciously gossipy, but Milton doesn’t shy away from difficult issues, such as the strange appeal of Stalin, which even the reader can feel. It is evident in the way Churchill and Roosevelt seemed to compete for his attention, even undermining each other to get it — see the former’s “naughty document” in which he proposed dividing Eastern Europe in half with Stalin, or the latter’s only half-joking suggestion that they sort out Britain’s India problem without Churchill. It was a rivalry that helped make them blind to — even naïve about — Stalin’s murderous intentions in Eastern Europe.

The story of the Grand Alliance is a familiar one, but Milton consummately retells it as a cinematic thriller. There is of plenty of heft in The Stalin Affair for the serious reader to enjoy, and lightness to enthrall the casual book buyer. Milton harnesses all his experience to deliver another exemplary piece of popular history.

This article was originally published in The Spectator ’s September 2024 World edition.

October 1, 2024

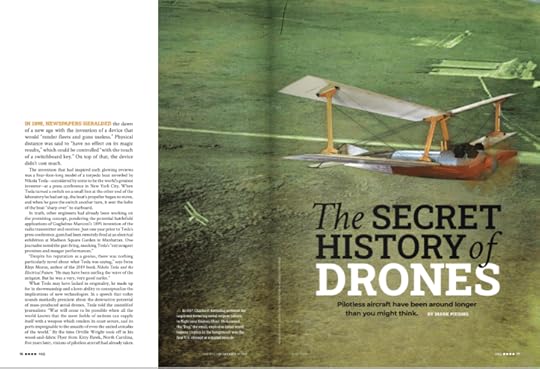

My latest for The Smithsonian’s Air and Space magazine…The Secret History of Drones

Pilotless aircraft have been around longer than you might think.

Pilotless aircraft have been around longer than you might think.I wrote this long read for The Smithsonian/ National Air and Space Museum just before Easter, and it is excellent that it has now been published.

I will publish the article in full below soon, but in the meantime, please read my four double-page features (and see the fantastic historical photographs) by…

Clicking here for the complete article

Clicking here for the digital edition of the magazine

With another feature waiting for a pub date and still another just completed, it is great to be described in my bio as “a frequent contributor” to the magazine.

June 27, 2024

Published on the 96th anniversary of Amundsen’s disappearance…This is my guest article for Get History on Amundsen’s Last Expedition

It was a great honour to be asked to write this guest article on Amundsen’s Last Expedition for Debbie Kilroy’s award-winning GetHistory for the 96th anniversary of the great explorer’s disappearance.

Read the article in full below—or the original by clicking this link, including the references for the quotes, which, for some reason, didn’t copy across.

Guest article by Mark Piesing

Shortly after 4pm on 18 June 1928, the flying boat carrying the great polar explorer Roald Amundsen on his last expedition was seen by a Norwegian fisherman flying over the Arctic ocean into ‘a bank of fog that rose up over the horizon…and disappeared before our eyes’ – and it was never seen again.

The Norwegian flag flying at the South Pole, after Amundsen had beaten Scott there in 1911. Image: © Olav Bjaaland, Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation.

The Norwegian flag flying at the South Pole, after Amundsen had beaten Scott there in 1911. Image: © Olav Bjaaland, Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation.The Roald Amundsen that most people know is the ruthless polar explorer, the first to sail through the Northwest Passage in 1905 and who beat Scott to the South Pole in 1911. A man nicknamed ‘the Governor’ because he brooked no dissent. An explorer at the peak of his game.

The Roald Amundsen most people haven’t heard of is the troubled aviation pioneer. The polar explorer-turned-aeronaut who liked to boast that in the early flights of pioneers such as the Wright Brothers he had seen the potential of aircraft to end the long, tedious forced march of the explorer. The man who experimented with man-lifting flying kites – then cutting-edge technology – in 1909; made his first flight in San Francisco in 1913; started flying lessons the following year; and was awarded Norway’s first civilian pilot’s licence in 1915.

Nor do most people know that Amundsen made three attempts to fly to the North Pole in the early 1920s, which ended variously in failure, public humiliation, personal bankruptcy, and depression. Four years that Amundsen described as ‘the most distressing, the most humiliating and altogether tragic episode of my life’ – and left him ‘depressed’, in a room in New York’s Waldorf Astoria in 1924, watching creditors’ final demands being pushed under his door.

This was a very public ordeal that ended only when Amundsen received a phone call from Lincoln Ellsworth, the son of a leading American industrialist, offering to fund his expeditions; a call that would eventually lead to him returning, with Ellsworth, to the Arctic in May 1925 for one more attempt to fly to the North Pole.

And nor do people know that Amundsen disappeared three years later, in June 1928, flying to join the search for Italian aeronaut Umberto Nobile and other survivors of the airship Italia, which had crashed a month earlier near the North Pole.

The train of events that led to Amundsen’s last expedition began three years earlier on 21 May 1925, when two state-of-the-art Dornier Wal flying boats took off from the frozen waters of Kings Bay, Svalbard, for the eight-hour, 500-mile flight to the North Pole. Amundsen and Ellsworth were soon crossing a ‘desolate and deserted’ landscape that would have taken weeks to do with skis and dogs.

Amundsen’s Donier on his unsuccessful attempt to reach the North Pole, 1925. Image © Anders Beer Wilse

Amundsen’s Donier on his unsuccessful attempt to reach the North Pole, 1925. Image © Anders Beer WilseBut once again, Amundsen’s attempt ended in disaster when they crash-landed 100 miles from the North Pole, the men in ‘the kingdom of death’ facing carving a take-off strip for the surviving aircraft out of the drifting sea ice before their food ran out.

After three and a half weeks and six take-off attempts, their fuel all but gone, they landed on the sea close to Svalbard. This time Amundsen was greeted as a hero, and he was sure of three things: he was going back to the Arctic; he was going to need an airship; and there was only one man who had an airship available – Italian engineer and aviator Umberto Nobile.

The only problem was that to buy it Amundsen would have to do-a-deal with the dictator of Fascist Italy, Benito Mussolini, who wanted to use the polar flight for propaganda purposes.

The Norwegian was obsessed with flying to the North Pole really for one reason: what lay beyond it. Largely forgotten today, maps in the 1920s had a large, shaded area on the other side of the North Pole from Europe usually labelled simply ‘unexplored region’. Called the last great hole in the map, it was believed to contain undiscovered land, rich in oil and other minerals; and it was the perfect location for the airfields needed to open the transpolar air route and to control the Arctic skies. For the Governor, it would be a suitable final triumph for his career, and the publicity caused by its discovery offered the promise of one last big paycheque.

It may seem a ridiculous idea to us today that Amundsen wanted to return to the Arctic in an airship, but in the 1920s airships were widely seen as the future of aviation, or a future. Compared to aeroplanes, they could fly for far longer and carry more supplies, and offered a stable platform for navigation and scientific research.

However, Amundsen had a problem: time. He was running out of it. The Governor had tried to get to the North Pole in 1922, 1923, 1924 and 1925 when he faced little or no competition, and on each occasion, he had failed. Now The New York Times announced that ‘MASSED ATTACK ON POLAR REGION BEGINS SOON … Ten Expeditions Will Probably Go into the Frozen North This Summer … Explorers Hope to Find a New Continent.’

The Norge taking off from Ciampino airport, Italy, before its adventure to the North Pole, 1926. © Aeronautica Militare.

The Norge taking off from Ciampino airport, Italy, before its adventure to the North Pole, 1926. © Aeronautica Militare.In May 1926, Amundsen, Ellsworth, and Nobile – with the support of Mussolini – joined multiple engineers and explorers in the race to be the first to fly to the North Pole, in what Science Monthly called ‘the most sensational sporting event in human history’. It was a competition that Amundsen and his partners won. On 14 May, the airship Norge, designed, built, and piloted by Umberto Nobile, landed in Teller, having taken off from Svalbard on the other side of the North Pole 71 hours earlier.

The Norge flight over the North Pole was a global event, a stunning success, and it was described as the one of the greatest achievements of the twentieth century. It took up three and a half pages of The New York Times. But the tensions that had been building before and during the flight exploded after it.

Amundsen had believed that Nobile was to be the equivalent of a hired driver, but the Italian wouldn’t accept that role. He had renegotiated his salary, demanded that he write one chapter of the lucrative book of the expedition, and insisted that the expedition name be changed to Amundsen-Ellsworth-Nobile.

This was too much for Amundsen, who accused him of repeatedly panicking while in command and of attempting to take credit for the expedition. That Nobile was called by Americans the ‘New Columbus’ really didn’t help his mood either.

Tragically, what Amundsen hadn’t understood was that aeronauts like Nobile had replaced the explorer as the public’s aspirational heroes. They were the astronauts of their day. Neither did he appreciate how Mussolini was able to mobilize the Italian diaspora via the Fascist League of North America to make sure Nobile was greeted as the hero everywhere he went in the United States.

Amundsen retired back to his beloved home in Uranienborg, Norway, where he swung between depression at how the last expedition of his career had turned out and fury at how Nobile and Mussolini had stolen the credit for it.

By contrast, Umberto Nobile had decided almost the moment they touched down in Alaska to return to the Arctic in a new airship. Stung by Amundsen’s public criticisms of him, Nobile wanted to show that the Italians could explore the Arctic by air without the Norwegian’s help, and he named this airship the Italia.

Umberto Nobile aboard the Italia, in April 1928. Image © Bundesarchiv.

Umberto Nobile aboard the Italia, in April 1928. Image © Bundesarchiv.‘We are quite aware that our venture is difficult and dangerous – even more so than that of 1926 – but it is this very difficulty and danger which attracts us’, said Nobile on the eve of his departure from Italy. ‘Had it been safe and easy other people would have already preceded us’.

Nobile’s flight in the Italia back to the North Pole should have been the easiest out of the five flights he planned in the summer of 1928, but it turned into the deadliest. In the early morning of 25 May, the Italiacrashed on to the ice, in terrible weather. With the gondola ripped off, the envelope of the airship floated away, leaving nine men on the sea ice – including a severely injured Nobile – and six still on board, who were never seen again. The only clue to their fate was a pillar of smoke on the horizon.

Like in a Marvel movie, the next day many of the world’s top explorers, including Roald Amundsen, were gathered at the Dronningen Restaurant in Oslo, when a telegram boy rushed in with a message from Svalbard. It was bad news: the Italia had not returned from its flight to the North Pole.

The mood of the dinner turned dark. What had happened to the airship? Where could it have crashed? How would the Italians cope on the ice floe?

A few minutes later the explorers were instructed to go straight to the defence ministry to plan a mission to look for Nobile and the crew of the Italia.

The room went quiet. Everyone looked at Amundsen. ‘There was no diner there who didn’t remember the bitter public quarrel between the two men’.

The great explorer’s reply was simple: ‘Tell them at once that I am ready.’

The airship Italia, in April 1928. Image © Bundesarchiv.

The airship Italia, in April 1928. Image © Bundesarchiv.Why did Amundsen agree to help Nobile? There were the rules of honour that Amundsen fully understood. There was the glory. Becoming the leader of the international effort to rescue the crew of the Italia would be a worthy end to Amundsen’s career. Perhaps Amundsen would be able to forgive Nobile for stealing the credit for the flight of the Norge if he could have the delicious final victory of grasping Nobile’s hand and pulling the Italian off the ice.

Or perhaps there was a darker motive. Amundsen didn’t expect – or want – to return from such a mission. He had heart problems and recently had been treated for cancer in Los Angeles, which may explain his recent decisions to settle his debts and give away some of his most prized possessions to friends.

What we do know is that the conversation took a dark turn when Amundsen was interviewed by journalist Davide Giudici in early June 1928. He pointed at a model of the kind of flying boat in which he had tried to reach the North Pole three years earlier. ‘If only you knew how splendid it was up there!’ he exclaimed. ‘That’s where I want to die, and I wish only that death will come to me chivalrously, will overtake me in the fulfilment of a high mission, quickly and without suffering.’

Unfortunately for Amundsen, Mussolini had the final word over who would lead the mission to find Nobile, and Il Duce didn’t want the Norwegian. Side-lined, he had to watch as his former right-hand man Riiser-Larsen become its de facto leader.

Soon it seemed like the whole world wanted to rescue Nobile and his men. In all, 23 planes and 20 ships from Denmark, Finland, France, Italy, Norway, the Soviet Union, Sweden, and the United States would be thrown into the desperate search to rescue the survivors.

Now Amundsen was under pressure. The press may have praised him for wanting to come to the aid of a man he hated, but this praise would turn into derision if he didn’t do something soon.

His solution was to launch his own independent rescue mission. But his reputation wasn’t what it had been. In the end, the French government agreed to supply a flying boat and provide a crew led by Captain René Guilbaud – one of their best pilots – and Lincoln Ellsworth would fund it. But the Latham wasn’t the state-of-the-art machine the Dornier Wal had been. Yes, it was a new French design built for transatlantic flights, but its wood–metal hull meant that it couldn’t land on the ice, and, underpowered, it needed a large stretch of open water to land safely. So, if Amundsen found the survivors the Latham could not land to rescue them. The best he could do would be a flyby to drop supplies. If that wasn’t bad enough, the Latham 47 itself was only the second of its type constructed, and a fire had destroyed the first (never a good omen).

But it was easy for Amundsen to push these worries to one side for now. For it was 16 June 1928. Nobile and his men had been stranded on the sea ice for three weeks, and Amundsen was only just now on the train leaving Oslo to rendezvous with his French plane at Bergen and fly up to Tromsø for the jump to Svalbard.

It was also 25 years, almost to the day, that he set sail on the expedition to discover the Northwest Passage – which he had done – and now, hundreds of people were on the platform to see him leave on this new mission.

Amundsen’s Latham 47, shortly before taking off – and disappearing – on 18 June 1928. Photograph © Anders Beer Wilse.

Amundsen’s Latham 47, shortly before taking off – and disappearing – on 18 June 1928. Photograph © Anders Beer Wilse.Early in the morning of 18 June Amundsen’s Latham 47 arrived in Tromsø harbour, after completing the 758-mile flight from Bergen. To his friend Fritz G. Zapffe, Amundsen seemed distant, as if there was something between them that the explorer could not share, and Zapffe would later interpret Amundsen’s mood as a premonition of his death. Perhaps the limitations of the design of the Latham for Arctic exploration that seemed theoretical in France were reality in Tromsø. He certainly complained about the machine to Zapffe – and wished he was flying a Dornier Wal instead. He even gave his friend his lighter to keep. He had taken it on every expedition, but Amundsen told Zapffe: ‘I will have no more use of it.’ He was reluctant to pose for the cameras while getting on the plane. He looked like a man resigned to his fate.

Despite his unease about the plane, Amundsen turned down suggestions from the Swedish and Finnish pilots to wait till the next day so they could all fly together for safety.

So, at 4pm, 18 June, the Latham, with Amundsen, René Guilbaud and four others on board, taxied across the water at Tromsø. It appeared to onlookers to be too heavy, perhaps even overloaded. The engines of the underpowered prototype design roared, and as it raced across the calm water of the harbour, it was clear it was struggling to take off. But at last the plane ascended. It was going to be a nerve-racking seven-hour flight to Kings Bay.

Later, the fisherman who saw the Latham flying into the cloudbank told journalists, ‘[T]he machine began to climb presumably to fly over it but then it seemed to me she began to move unevenly.’ It is well known that flying in fog causes disorientation and loss of spatial awareness.

Two radio messages were received from the Latham. At 6pm, when it had been in the air for two hours: ‘Nothing to report.’ And then, just after 7pm, the mysterious ‘Do not stop listening. Message forthcoming.’

Whatever that message was, the operator didn’t have time to send it. A coal ship on its way up to Kings Bay later reported hearing a faint SOS. It is possible that these were the last distress calls ever to be heard from Amundsen and the Latham.

Now the search for Amundsen began to gain momentum, taking away many of the aircraft and boats deployed to search for Umberto Nobile and the survivors of the Italia. The difficulty was that no one really knew whether they were looking in the right place or not. It was a case of dropping a pin in the rather large hole in the map.

The Nobile monument in Tromsø, commomorating all those who perished in the Italia and subsequent rescue attempts. Image © Sparrow.

The Nobile monument in Tromsø, commomorating all those who perished in the Italia and subsequent rescue attempts. Image © Sparrow.It seemed wrong to many Norwegians that Amundsen had disappeared but that Nobile was found alive four days later, on 22 May. On 16 July, the day the Norwegians gave up the hunt for Amundsen, the survivors of the Italialanded at the Norwegian port of Narvick, to be met by hundreds of Norwegians standing on the quayside in silence, and local newspapers calling for ‘Death to Nobile’.

Only three confirmed pieces of Amundsen’s plane have ever been recovered. One of the wing floats of the Latham was recovered from the sea later in the summer; the struts and wires were still attached to it, indicating it had been torn off the plane. A fuel tank was found near Trondheim, Norway, that same year; another a year after.

The fate of Roald Amundsen and the Latham may never be known. Plenty of wreckage was found that could have been from Amundsen’s plane but couldn’t be confirmed as such, and even some that might have been deliberate fraud, as well as many sightings of the plane, and Amundsen, alive, as far away as Mexico.

The hunt for Roald Amundsen continues to this day. In 2012, underwater drones were employed to sweep the seafloor for wreckage of the Latham, to no avail. It may be that his fate will be finally revealed only by the melting sea ice.

May 29, 2024

I am a Finalist for the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards!

It is an absolute honour to have been shortlisted as a Finalist at the prestigious Aerospace Media Awards along with so many great journalists for my BBC Future feature, The Robot Aircraft with a Nightmarish Mission.

I don’t expect to win, but it will be great to be at the dinner!

I want to thank my brilliant editor, Stephen Dowling, for seeing the potential of this forgotten story from the beginning of the Cold War.

My latest feature for BBC Future has been published: The satellites using radar to peer at earth in minute detail

Synthetic aperture radar (SAR) allows satellites to bounce radar signals off the ground and interpret the echo – and it can even peer through clouds.

I will post the full feature here on a personal website in a week or two. In the meantime, read it in full on BBC Future here.

May 23, 2024

My latest book review for The Spectator (USed): A skilful retelling of One of World War Two’s most dramatic stories.

My review in print!

My review in print!In The War We Won Apart Nahlah Ayed transports the reader to World War Two as experienced by the brave SOE agents who landed behind enemy lines.

Read my latest book review for The Spectator World edition in full below – or read the original, by clicking on this link.

Around lunchtime on a late September day in 1944, a young woman stepped into one of the most fashionable cafés on the Champs-Élysées. Her eyes still scanned the room for threats, even though her war had been over for many months.

Known variously as Suzanne, Madeleine, Blanche, Ginnette or Tony, she had “amassed names and personas just as other women of her years and beauty amassed admirers. And she had amassed those too” in the service of her country. Two such admirers now sat opposite her in the café, and she had to decide which one she was going to spend the rest of her life with, and which she would never see again…

Such is the climax of the epic story of love and betrayal that Nahlah Ayed tells, using unpublished interviews and archival and personal documents. Sonia Butt and her husband Guy d’Artois hailed from very different worlds. They met while training in Scotland to be agents of Britain’s Special Operations Executive (SOE), fell in love and married — a marriage that doomed them to fight their war apart. For their own safety, they were sent to fight the Nazis separately, at opposite ends of France.

Inspired by the tactics of such groups as the Irish Republican Army, the SOE was a voluntary force formed by Winston Churchill in 1940 to “set Europe ablaze” through espionage, sabotage and aiding local resistance fighters, and repurposed in late 1943 to impede German reinforcements from reaching the Normandy front lines on, and after, D-Day. But The War We Won Apart is really lit up by one person: Sonia. SOE agents were supposed to be “ordinary people trained to do extraordinary things.” She was anything but.

“Sonia knew trauma early, the way one knows a long-time neighbor,” Ayed writes. Taken to live in France by her vindictive mother when she was three, she suffered physical abuse and malnourishment. But she learned to speak French fluently, an attribute that would prove crucial in her later work.

On the eve of war, fifteen-year-old Sonia was abandoned by her mother and made the trip back to safety in England alone. Later, while she was working in an administrative branch of the WAAF (Women’s Auxiliary Air Force), her father arranged for her to have an interview for a more interesting clerical job, but when she met Major Buckmaster, head of the SOE’s French section, he had other ideas. He asked her whether she would be interested in working behind enemy lines in France. She answered simply, “How do you get there?”

Guy’s family had lost nearly everything in the Great Depression. It was no surprise that he was one of the first Canadians to sign up to fight. While his dreams of being a pilot, or even just an ordinary soldier, were broken because of a childhood illness, he headed to war as a physical training instructor. Ayed observes that “Guy wasn’t the sort who could possibly sit out the war; it called out to him like a long-lost friend.”

The War We Won Apart is a true story that could easily have been told as a James Bond-style thriller where female spies are “beautiful,” men are strong, silent types, the partying is hard, and women are fighting for their right to kill — and die — for their country.

However, Ayed has covered “hot zones” around the world as a journalist, from the Arab Spring to Putin’s invasion of Crimea. Her experience elevates The War We Won Apart from a good update of Ian Fleming to an extraordinary story. She skillfully transports the reader to World War Two as experienced by the brave SOE agents who landed behind enemy lines. Ayed manages to tell the story of the British Sonia and French-Canadian Guy with skill and sympathy, showing a real understanding of how love is forged — and forgotten — in the white heat of war, as well as the opportunities for reinvention that war may give its fortunate survivors, transforming young waifs and strays into skilled professionals, leaders and celebrities.

When Sonia was parachuted into France in May 1944, she became one of the youngest SOE agents ever to do so. Seeing that Le Mans was “crawling with German troops and collaborators,” with General Erwin Rommel’s HQ and the headquarters of the German Seventh Army nearby, she realized she would have to “live more openly than she’d intended” if she wanted to stay alive. This meant living in a little house one street away from the town center, and frequenting black-market restaurants and cafes, under the noses of the Germans who hunted her.

Young and blonde, she was assumed to be German, a collaborator or a German officer’s girlfriend. Her situation, Ayed tells us, “wasn’t just uncomfortable; it was terrifying.”

Sonia had been sent to France to be a messenger. But, shorthanded, the “Headmaster” network quickly employed her to go far beyond the limited roles that women agents were supposed to play behind enemy lines. Instead of passing on messages, she was visiting contacts, sussing out new recruits, training them to how blow things up — one of her specialties — and how to fire a Bren gun, using German convoys for target practice.

All these strands collide in one of book’s most dramatic moments, vividly related by Ayed. One day, Sonia was chatting to a German officer in a black-market restaurant when her handbag slipped off her chair and hit the floor with “the unmistakable thud of a heavy object.” The object was her pistol.

Sonia saw the officer reach down to pick up the bag — and she was done for, unless she killed him first. Just “a breath away from being found out,” she managed to get to it first. The next day she discovered that he was the head of the local Gestapo.

Sonia’s war brought other complications. By a strange twist of fate, her network leader turned out to be Sydney Hudson, a man with whom she’d gone through SOE training and whose advances she had spurned. Meeting him unexpectedly in the field, she wondered if they were fated to be together. Ayed vividly conveys Sonia’s surprise and confusion at this further complication in her life, and delicately examines what it means to betray the man you love in a time of war, when he may already be dead, and you may be soon.

Meanwhile, for Guy, hundreds of miles to the south, the euphoria of landing in one piece was replaced by “the sinking realization that there was no turning back, no way out… he had no uniform, no trained army to help him in his fight, and no Sonia.” Yet Ayed fails to bring the same depth to Guy she does to Sonia. Perhaps as a reflection of his personality, or the time he lived, Guy stubbornly remains opaque to the reader: strong, silent and heroic.

Guy’s mission was to turn the young men in the forests outside the strategic city of Charolles into a fighting force strong enough to take on the Wehrmacht, despite their suspicions about British intentions and a lack of weapons. His “hostility to oversight and impatience with slow progress” were good qualities for such a task.

Ayed skillfully teases out evidence of the personal cost to him of his growing reputation as “Michel le Canadien” after his men’s successful attacks on German posts, convoys and railways. Sonia wanted to avoid risk; Guy relished it. He disguised himself as a laborer to smuggle himself into a German base. He traveled to Gestapo-controlled Lyon at least once for a “vacation,” and he was even at the handover of a 2 million-franc ransom given to two German officers for the freedom of seven captured agents. But wherever Guy was, he went to sleep worrying about Sonia.

Nor did this end after the war, either; not only does Ayed elegantly resolves the love triangle at the heart of the book, but there is an extended coda, focusing on Sonia and her partner’s status as reluctant celebrities and her attempts to have her achievements recognized by the British government, which concludes the story in a manner both insightful and satisfying.

Aspects of this story have been told before, but Ayed’s The War We Won Apart retells it on an epic scale. Despite its being a love story, those readers looking for a page-turning World War Two tale will not be disappointed, and those keen to steer clear of Ian Fleming’s legacy will find a great deal to like here as well. With the insight of her own experiences, Ayed colorfully retells the story of Sonia and Guy on a scale that speaks to the fears — and hopes — of a world on a brink of another global conflict.

This article was originally published in The Spectator ’s June 2024 World edition.

My latest book review for The Spectator: A skilful retelling of One of World War Two’s most dramatic stories.

My review in print!

My review in print!In The War We Won Apart Nahlah Ayed transports the reader to World War Two as experienced by the brave SOE agents who landed behind enemy lines.

Read my latest book review for The Spectator World edition in full below – or read the original, by clicking on this link.

Around lunchtime on a late September day in 1944, a young woman stepped into one of the most fashionable cafés on the Champs-Élysées. Her eyes still scanned the room for threats, even though her war had been over for many months.

Known variously as Suzanne, Madeleine, Blanche, Ginnette or Tony, she had “amassed names and personas just as other women of her years and beauty amassed admirers. And she had amassed those too” in the service of her country. Two such admirers now sat opposite her in the café, and she had to decide which one she was going to spend the rest of her life with, and which she would never see again…

Such is the climax of the epic story of love and betrayal that Nahlah Ayed tells, using unpublished interviews and archival and personal documents. Sonia Butt and her husband Guy d’Artois hailed from very different worlds. They met while training in Scotland to be agents of Britain’s Special Operations Executive (SOE), fell in love and married — a marriage that doomed them to fight their war apart. For their own safety, they were sent to fight the Nazis separately, at opposite ends of France.

Inspired by the tactics of such groups as the Irish Republican Army, the SOE was a voluntary force formed by Winston Churchill in 1940 to “set Europe ablaze” through espionage, sabotage and aiding local resistance fighters, and repurposed in late 1943 to impede German reinforcements from reaching the Normandy front lines on, and after, D-Day. But The War We Won Apart is really lit up by one person: Sonia. SOE agents were supposed to be “ordinary people trained to do extraordinary things.” She was anything but.

“Sonia knew trauma early, the way one knows a long-time neighbor,” Ayed writes. Taken to live in France by her vindictive mother when she was three, she suffered physical abuse and malnourishment. But she learned to speak French fluently, an attribute that would prove crucial in her later work.

On the eve of war, fifteen-year-old Sonia was abandoned by her mother and made the trip back to safety in England alone. Later, while she was working in an administrative branch of the WAAF (Women’s Auxiliary Air Force), her father arranged for her to have an interview for a more interesting clerical job, but when she met Major Buckmaster, head of the SOE’s French section, he had other ideas. He asked her whether she would be interested in working behind enemy lines in France. She answered simply, “How do you get there?”

Guy’s family had lost nearly everything in the Great Depression. It was no surprise that he was one of the first Canadians to sign up to fight. While his dreams of being a pilot, or even just an ordinary soldier, were broken because of a childhood illness, he headed to war as a physical training instructor. Ayed observes that “Guy wasn’t the sort who could possibly sit out the war; it called out to him like a long-lost friend.”

The War We Won Apart is a true story that could easily have been told as a James Bond-style thriller where female spies are “beautiful,” men are strong, silent types, the partying is hard, and women are fighting for their right to kill — and die — for their country.

However, Ayed has covered “hot zones” around the world as a journalist, from the Arab Spring to Putin’s invasion of Crimea. Her experience elevates The War We Won Apart from a good update of Ian Fleming to an extraordinary story. She skillfully transports the reader to World War Two as experienced by the brave SOE agents who landed behind enemy lines. Ayed manages to tell the story of the British Sonia and French-Canadian Guy with skill and sympathy, showing a real understanding of how love is forged — and forgotten — in the white heat of war, as well as the opportunities for reinvention that war may give its fortunate survivors, transforming young waifs and strays into skilled professionals, leaders and celebrities.

When Sonia was parachuted into France in May 1944, she became one of the youngest SOE agents ever to do so. Seeing that Le Mans was “crawling with German troops and collaborators,” with General Erwin Rommel’s HQ and the headquarters of the German Seventh Army nearby, she realized she would have to “live more openly than she’d intended” if she wanted to stay alive. This meant living in a little house one street away from the town center, and frequenting black-market restaurants and cafes, under the noses of the Germans who hunted her.

Young and blonde, she was assumed to be German, a collaborator or a German officer’s girlfriend. Her situation, Ayed tells us, “wasn’t just uncomfortable; it was terrifying.”

Sonia had been sent to France to be a messenger. But, shorthanded, the “Headmaster” network quickly employed her to go far beyond the limited roles that women agents were supposed to play behind enemy lines. Instead of passing on messages, she was visiting contacts, sussing out new recruits, training them to how blow things up — one of her specialties — and how to fire a Bren gun, using German convoys for target practice.

All these strands collide in one of book’s most dramatic moments, vividly related by Ayed. One day, Sonia was chatting to a German officer in a black-market restaurant when her handbag slipped off her chair and hit the floor with “the unmistakable thud of a heavy object.” The object was her pistol.

Sonia saw the officer reach down to pick up the bag — and she was done for, unless she killed him first. Just “a breath away from being found out,” she managed to get to it first. The next day she discovered that he was the head of the local Gestapo.

Sonia’s war brought other complications. By a strange twist of fate, her network leader turned out to be Sydney Hudson, a man with whom she’d gone through SOE training and whose advances she had spurned. Meeting him unexpectedly in the field, she wondered if they were fated to be together. Ayed vividly conveys Sonia’s surprise and confusion at this further complication in her life, and delicately examines what it means to betray the man you love in a time of war, when he may already be dead, and you may be soon.

Meanwhile, for Guy, hundreds of miles to the south, the euphoria of landing in one piece was replaced by “the sinking realization that there was no turning back, no way out… he had no uniform, no trained army to help him in his fight, and no Sonia.” Yet Ayed fails to bring the same depth to Guy she does to Sonia. Perhaps as a reflection of his personality, or the time he lived, Guy stubbornly remains opaque to the reader: strong, silent and heroic.

Guy’s mission was to turn the young men in the forests outside the strategic city of Charolles into a fighting force strong enough to take on the Wehrmacht, despite their suspicions about British intentions and a lack of weapons. His “hostility to oversight and impatience with slow progress” were good qualities for such a task.

Ayed skillfully teases out evidence of the personal cost to him of his growing reputation as “Michel le Canadien” after his men’s successful attacks on German posts, convoys and railways. Sonia wanted to avoid risk; Guy relished it. He disguised himself as a laborer to smuggle himself into a German base. He traveled to Gestapo-controlled Lyon at least once for a “vacation,” and he was even at the handover of a 2 million-franc ransom given to two German officers for the freedom of seven captured agents. But wherever Guy was, he went to sleep worrying about Sonia.

Nor did this end after the war, either; not only does Ayed elegantly resolves the love triangle at the heart of the book, but there is an extended coda, focusing on Sonia and her partner’s status as reluctant celebrities and her attempts to have her achievements recognized by the British government, which concludes the story in a manner both insightful and satisfying.

Aspects of this story have been told before, but Ayed’s The War We Won Apart retells it on an epic scale. Despite its being a love story, those readers looking for a page-turning World War Two tale will not be disappointed, and those keen to steer clear of Ian Fleming’s legacy will find a great deal to like here as well. With the insight of her own experiences, Ayed colorfully retells the story of Sonia and Guy on a scale that speaks to the fears — and hopes — of a world on a brink of another global conflict.

This article was originally published in The Spectator ’s June 2024 World edition.

April 16, 2024

My latest piece for BBC Future has just been published: Sweden has long opposed nuclear weapons – but it once tried to build them

In the years after World War Two, neutral, peace-loving Sweden embarked on an ambitious plan – build its own atomic bomb.

Read it by clicking on this link

I will post it in full below in the next week or so.

April 8, 2024

My latest opinion piece for The Bookseller: The streaming wars are over, but what does this mean for writers hoping to sell their work?

Read my latest opinion piece for The Bookseller in full below, or by following this link.

Find out more about my book N-4 DOWN the hunt for the Arctic airship Italia here.

One of the most common questions I get asked as an author is: when is Netflix going to turn your book into a Hollywood film? But I don’t have the heart to tell my readers that it has never been an easy process to get to that point, and that the end of the streaming wars may have made it even harder.

The streaming wars began in 2019 when Disney launched its streaming service, Disney+, to rival Netflix’s dominance in this market. Five years later it is hard to believe that they have come to an end when Netflix’s $20m-per-episode science-fiction epic “3 Body Problem” – its most expensive scripted series ever, based on the novel by Cixin Liu – was launched on 21st March, outspending both Apple TV’s lavish “Masters of the Air” and Disney+’s glossy “Shōgun”.

But end the wars have, in a post-lockdown world of falling subscribers, staggering debt, cuts, strikes, recriminations… and Netflix’s victory. In 2023 alone, the Hollywood studios lost more than $5bn in their attempts to compete with Netflix. Disney has pledged to cut $5.5bn in costs, including $3bn in non-sports content this year, and raise revenue by once again licensing more content to arch-rivals Netflix. Its c.e.o. Bob Iger pointedly stated that “a lot of decisions were made to prop up the company’s flagship streaming service, Disney+, and beckon more customers”.

The bad news for authors is that expensive scripted shows, often adapted from books, are among the first to be cut. In the US, releases have dropped from 633 in 2021–22 to 481 a year later, with Netflix cutting its releases from 107 to 68 titles, Peacock by 20, Hulu by 11, HBO Max by nine, and Paramount by four – and the future doesn’t look any better. According to The Hollywood Reporter, “Only Amazon has kept up the number of series it ordered in 2023, suggesting 2024 will see a decline in US shows across nearly every major streamer.”

The Financial Times sums it up: “For much of the past four years, the entertainment industry spent money like drunken sailors to fight the first salvos of the streaming wars. Now, we are finally starting to feel the hangover and the weight of the unpaid bar bill.” Unfortunately, the bar bill will be paid by all the actors, production staff, technical teams and marketing professionals who lose their jobs.

Might authors who want their books to be made into a film be another – if minor – casualty of the end of the streaming wars? I decided to ask a couple of Hollywood insiders to find out.

Stephen Robert Morse is the producer of the Emmy-nominated documentaries “Amanda Knox” (Netflix) and “In the Cold Dark Night” (ABC/Hulu/Sky). His latest is out on Netflix in June.

“The streaming wars are over, and everyone feels decimated,” Morse tells me over a coffee at the heaving Groucho Club (no sign of the end of the streaming wars here). “You can’t talk to a reputable producer in this business who won’t have had a network drop one of their projects in the past year.” Morse thinks that now, producers like him “aren’t going to take 10 books any more, and then pitch five of them. They’re going to take three books and pitch three.”

Books are one part – albeit the most important part – of the expensive package of “sales materials” he needs to pitch to a studio, involving money that must be spent without guarantee of success. “So, we can’t waste time and resources on projects unless we are 100% sure that this project has a fighting chance. Otherwise, we’re simply burning money.”

The bad news for authors is that expensive scripted shows, often adapted from books, are among the first to be cut. In the US, releases have dropped from 633 in 2021-22 to 481 a year later

There are tales of production companies not optioning non-fiction books because the story was in the public domain. I ask him, is there any truth in that?

“For writers, there was a time when people were trying to just acquire as much IP as possible,” he says. “But I think those days are a little over now, with producers more comfortable using stories in the public domain.” It is more about “good projects with good ideas and good people”.

My phone rings at 3.30pm – 7.30am in LA – and I have a seven-minute window to talk to a Hollywood studio executive on condition that he is not named. What he tells me is good news for the future of book adaptations, kind of.

“Whatever you want to call it, the reduction in the volume of shows means it’s going to be harder to get things made, and that means fewer opportunities,” he says. “But what this creates is more of a dependence or interest in book adaptations among the studios. “When you step back and look at what has worked over the past five years it has been book adaptations. TV shows and films based on books have a higher hit rate, just in terms of their quality, because a book gives the studios a general framework for a story, the world it is in, the details, the themes, and the characters.”

He makes the point that HBO is supposed to be the standard bearer for original drama, but many of its recent hits have been based on books, as are all the shows I mention at the start of this piece. “Books are also important when it comes to marketing the final product. It is such a crowded marketplace, shows can simply disappear when they are launched, and marketing dollars are being cut across the board, so the question is how do you build anticipation for your show? Having a built-in audience really helps with that.”

It isn’t just the bestsellers that studios want, either. There are few books that can deliver millions of viewers. “So you are also looking for smaller books that have created a good world and can be a great starting point.”

While there are some positive signs, the fallout from the end of the streaming wars – or at least, the first phase of it – looks set to continue for those who work in the industry, as streaming remains a business with very low revenue per head. YouTube now has the attention of every age group, and the streaming platforms face disruption with the return and rebranding of – profitable – free ad-supported linear or cable television (FAST).

What can authors do to increase the chances that their book is made into a film in this increasingly uncertain environment? “I would just say think commercially minded, and think, what do audiences want to read or learn about rather than what interests you,” says Morse. “Look up a musician on Spotify and write about the one who had 10 million listeners this month and not 600,000 because this is what we do when deciding what to pitch.”

“What I would say to a lot of writers is that a lot of production companies are looking for something to hook into,” says the studio executive, “and so I would be forming relationships with production companies that you can trust to put your book in front of the right people.”