Mark Piesing's Blog, page 9

December 19, 2022

What if your work today was marked by your old school teachers? Well, my new book N-4 DOWN was….

I never got an A* when I was at school. Will I get one now?

I never got an A* when I was at school. Will I get one now?“One of the highlights of my role back at Trinity School of John Whitgift is catching up with former classmates. In this instance, Mark Piesing. His very successful book, ‘N4 -Down: The Hunt for the Arctic Airship Italia’, on Umberto Nobile’s ill-fated mission, was just one of our topics of conversation. And then I thought – what would our current History and Politics department think of it? Julian Timm, Trinity history and politics teacher, got out his red pen to mark Mark’s homework. Read on to see if he got an A*…..”

Jason Court, Director of Development

Read Julian’s comments below – or Jason Court’s original LinkedIn article here.

Find out more amzn.to/3oOvriG

What the critics thought shorturl.at/fyNT1

Listen to a short interview https://bit.ly/3h0mAK9

Watch the trailer https://bit.ly/3Cn3wOQ

Here are Julian’s comments.

The titans of Trinity’s History Department in the 1980’s when the author was a pupil here – Fairman, Jardine, Cheyne, Peak – knew that History was nothing if it not a great story – and they told a few. But they were also about rigour – checking your sources, backing up your arguments, explaining your evidence. Piesing ticks all those boxes, and those former mentors would approve.

The “Zeppelin” era of airships (other brands were available) continues to hold a great fascination. Although it spanned a period of time from the end of the 19th century, including numerous German bombing raids over Britain during WWI, and into the 1930s, it is most closely associated with the glamour of the 1920s. This was the era of Gatsby, of the excesses of Weimar Germany and, more pertinent to this story, the rise of Mussolini and his Fascist party in Italy. The great burst of post war confidence seen in so many different spheres of human activity, expressed itself also in enormously ambitious new engineering projects, which the airships perhaps best expressed through their massive size (the “Italia” or “N-4” described in this book was 100 metres long, whilst the Graf Zeppelin was over 200 metres) and as yet unparalleled range, with transatlantic crossings becoming increasingly common. The mast on top of the Empire State Building was originally designed as a mooring for airships. One might also say, however, that this was also an era of great hubris, summed up by the Wall Street Crash and a disastrous global depression that followed, and which arguably took the world into war in 1939. And here we touch on another enduring fascination – with human failure and disasters. We’re all familiar with the story of the Titanic, perhaps made more popular because of the contrast between enormous opulence on board the ship reduced ultimately to nothing. Add to this the allure of polar exploration, and the thrill of a race-against-time rescue mission played out in the media, and you have all the ingredients of a thrilling yarn, unbelievable were it not true, and brilliantly captured in Mark Pieling’s book N-4 Down.

This tells the story of the ultimately disastrous voyage of the Italia, officially named N-4, which left Milan in 1928 under the leadership of the appealing Umberto Nobile, heading for the North Pole with a crew of 20. With hindsight the omens from the outset were not good. The initial journey to Germany took 30 hours as it narrowly avoided lightning strikes and endured significant wind damage to one of the tailfins, causing a 10 day delay while spares were sent from Italy, before finally resuming their voyage North.

On the 11th of May, General Nobile began the first of three planned polar flights, setting off from their base at King’s Bay in Svalbard, a collection of islands in the middle of the Arctic Ocean. This first flight had to be abandoned after 8 hours due to the build up of thick ice on the airship. On the 15th of May a second flight set off and successfully completed 2500 miles in 60 hours in perfect conditions, gathering valuable data on meteorology and magnetic forces in the polar region; this was not all a story of failure. However, it was the third and fateful voyage departing on the 23rd of May which forms the focal point of this book. With the advantage of a tailwind the Italia reached the North Pole nineteen hours later and, despite not being able to land crew members on the ice as planned, they were able to take further measurements. They proceeded whilst still above the Pole to celebrate their extraordinary achievements in perhaps what might otherwise be seen as a caricature – dropping a wooden cross that had been personally given to them by the Pope, drinking a toast of eggnog to the leader Nobile, and starting up the gramophone which they had carried on board to play the Italian Fascist anthem “Giovinezza”. Tragically, though with hindsight entirely predictably, the same helpful tailwind that had taken them so swiftly to the Pole now severely hindered their return journey, and after battling vainly against the worsening weather and wind they crash landed on the ice on the 25th of May. This is no spoiler of the book’s story – we are made well aware of this from the outset – but this event forms the pivot on which the book hinges.

Piesing’s account tells the story of Nobile’s early successes, heroically traversing the Arctic in 1926 with American Lincoln Ellsworth and Norwegian Roald Amundsen on the Norge airship, for which he was feted by Italian dictator Mussolini on his return. It delves into the murky political intrigues that saw Mussolini exploiting such successes to extol the virtues of Italian Fascism, whilst he would be sure to distance himself from the subsequent failure of Nobile’s doomed flight in 1928.

But the guts of the story, and what grips the reader, is the subsequent account of attempted rescue and survival of those stranded on the icy wasteland. There are echoes which remind one of Shackleton’s rescue voyage to South Georgia, and of Scott’s doomed trek back from (near) the South Pole – one of the Italia’s survivors, Finn Malmgren, who was only crew member with experience of ice trekking had been badly injured and, similar to the story of Captain Oates, twice had to be forcibly restrained from drowning himself. Roald Amundsen became part of a multi-national rescue mission, which itself was heroic and chaotic in equal measure. The efforts of the eight nations were largely uncoordinated; air drops were made to survivors spotted near the crash site, but many of these smashed on the rocks; rescue planes attempted landings unsuccessfully, adding rescuers to the body of men who required rescuing from the ice; Amundsen himself was aboard a flight which disappeared, his body never to be found. In the end 6 of Italia’s crew were rescued 47 days after the crash, but 17 crew and rescuers died.

The story has prompted many attempts to capture it over the years. As early as 1928 the Soviet documentary film “Heroic Deed Among the Ice”, describes the rescue mission of the Soviet icebreaker Krassin, whilst the story of the Italia disaster was made into a film in 1969, titled “The Red Tent” and starring Sean Connery as Amundsen.

It has similarly spawned many theories as to the causes of the crash. Clearly the poor weather and winds on its final flight were key, but so may have been possible damage caused when clearing the ice from the canopy after the first and second flights. At the time most of the blame was placed squarely on Nobile – the Italian government launched a smear campaign which permanently damaged his reputation, though it should also be acknowledged that he appears to have been awake for over 72 hours at the time of the crash and made what can at best be described as questionable judgements.

Piesing tells all this with a sense of the thrill of adventure, and a clear empathy and admiration for those at the heart the story, especially Nobile. But this is not just a rollicking boys own adventure – though it is very much that too. He takes time to delve into the fascinating and sometimes bizarre characters of the supporting cast. We meet the extraordinary Italo Balbo, heroic Italian aviator and Hollywood idol, beloved and a little feared by Mussolini and who appeared determined not to be outshone by Nobile. Amundsen turns out to be a multi-layered figure – bankrupt and a serial adulterer, who had told all but his immediate circle in 1911 that he was heading for the Arctic, when in fact en route to his successful trek to the South Pole in order to gain what advantage he could over his rivals. And there is time too for side stories – when Nobile was invited to Washington in 1926 to celebrate his crossing of the Arctic, he took his dog Titina with him to the White House where she relieved herself on the carpet.

It is, in the end, an account of human endeavour and human failure in equal measure. The more one reads of any of these extraordinary figures such as Scott or Shackleton one realises that, for all their achievements, they were riddled with flaws, yet possibly without them they would never have attempted what they did. These are not the feats of rationale people.

As Nobile himself later wrote in his memoirs about his successful 1926 flight: ‘Three big heads had to live under the same hat: Amundsen, Ellsworth, Nobile. None of them was easy, none was made for giving in.’

Report thisRemove tag

December 6, 2022

Smells like victory: what Skunk Works can teach us about extreme innovation (UPDATED)

The remarkable feats of Lockheed’s elite warplane design team have inspired several corporate imitators. Are any of the rules set by its visionary creator in 1943 applicable in business today?

My very well received front page feature for Raconteur appeared in print on page 4 and 5 Enterprise Agility report tucked inside The Times newspaper.

You can find the read article below – or click here for the original and/ or full report it is a part of.

“Mark Piesing an incredible and insightful article on my hero Kelly Johnson. The Michigander that was described as “That damn Swede can see air”. I was honoured to have been interviewed by you Mark, and grateful to share our philosophy on radical innovation at Hyox Thank you again.”

“Great article by Mark Piesing about Kelly Johnson’s Skunk Works. Well balanced, and emphasises the importance of integrating the results into the parent organisation and especially the value of failure. And nice to be quoted

At the height of the second world war, US aerospace giant Lockheed entrusted Clarence “Kelly” Johnson to lead a crack unit of engineers on a series of top-secret projects for the government. Over the next three decades, Johnson’s Skunk Works division designed and built a series of advanced aircraft, including the U-2 and SR-71 Blackbird high-altitude reconnaissance planes, which the CIA used to spy on its Communist foes in the cold war.

These innovators pushed the limits of what was technically possible, working to incredibly short schedules and strict budgets. Their feats earned Skunk Works a near-legendary status in the engineering world.

The team exhibited many of the key characteristics of modern enterprise agility. Operating away from the prying eyes of Lockheed management, Johnson used memorable mantras, including “keep it simple”, and applied 14 rules and practices. His aim was to inspire the focused and responsive approach required in pursuit of the maximum competitive advantage over a rival – or, in this case, America’s numerous enemies.

But, as many would-be imitators in business have since discovered to their cost, it’s not easy to duplicate the Skunk Works formula successfully. Even household names have tried and failed to do that.

Xerox – a copier company by more than name – followed much of the Skunk Works playbook when it set up an R&D facility in Palo Alto, California, in 1969. “The goal was to come up with radical new ideas in the centre of computer science and technology, far away from Xerox’s east-coast headquarters,” explains James Hayton, professor of innovation and entrepreneurship at the University of Warwick. “And, lo and behold, it came up with some brilliant, brilliant technology.”

Its computing innovations included a user interface featuring multiple windows and graphic icons. Unfortunately, such advances were too far ahead of their time for the operating companies, which weren’t interested.

It’s a daunting precedent for any firm thinking about replicating the Skunk Works model today. One of them is Hyox, a liquid hydrogen manufacturer that has created a Skunk-like facility in Toronto to develop its alternative fuel. Glenn Martin, the firm’s co-founder and chief architect, is familiar with the potential pitfalls of this approach.

“I worked on manned space systems at the McDonnell Douglas Phantom Works in the 1980s, including the lifeboat programme for the International Space Station,” he says. “While the work was exciting, we lacked an inspirational leader like Kelly Johnson. I didn’t experience that level of entrepreneurial energy until I met Elon Musk and started working with SpaceX.”

Not a plug-and-play optionJohn Clegg is chief technology officer at Hephae Energy Technology, a startup specialising in geothermal power generation. He believes that many business leaders who think they’re following the Skunk Works model “simply say: ‘OK, let’s create a Skunk Works. We’ll put these people in a separate location and see what they come up with.’ They don’t really understand how it’s done.”

Clegg continues: “I was once put in charge of a team with the task of developing the technology for an autonomous well-drilling robot. We moved into a different building to work on the project. We developed the tech within two years, but it took four more to commercialise it. That was because we, working as a separate organisation, couldn’t draw on the same manufacturing team, sales people and customers as the rest of the company.”

It’s worth examining precisely which ingredients made the original Skunk Works a success. First, there was the man himself. By the time his division was conceived at the height of the second world war, Kelly Johnson was already a highly respected aircraft designer and had become a senior executive at Lockheed.

Second, there was his decision to separate his team physically from the wider organisation – initially inside a circus tent erected on the site – and to ban his fellow Lockheed executives from visiting. This was possible only because of Johnson’s power within the firm and the top-secret work he was undertaking.

Kelly Johnson was obviously a fantastic leader and a very creative engineer, so that cannot be discounted in explaining the success of Skunk Works

Lastly, Johnson insisted on – and was granted – absolute authority within Skunk Works. This gave him the freedom to implement a range of now-familiar techniques for creating an agile business. It featured a small, hand-picked team of elite professionals; close cooperation among different disciplines; and minimal bureaucracy.

Crucially, the team’s members knew that failing fast wouldn’t be a career-limiting move, according to Paola Criscuolo, professor of innovation management at Imperial College Business School.

“Kelly Johnson was obviously a fantastic leader and a very creative engineer, so that cannot be discounted in explaining the success of Skunk Works,” she says. “But the 14 rules he put in place were important.”

One of these was as follows: “A very simple drawing and drawing release system with great flexibility for making changes must be provided.” The implied instruction here was to test any given design frequently for flaws and, if any come to light, stop working on it, quickly adjust the plan to solve them and then move in the new direction apace.

This ‘fail fast, learn fast’ approach was particularly important, given that Skunk Works was often operating on extremely tight schedules. Criscuolo notes that “Johnson had to build his very first jet fighter in only 180 days”.

Integrating with the wholeSkunk Works did have a significant and fortunate advantage over virtually all of its would-be imitators: it already had a big-spending customer – Uncle Sam – eagerly awaiting his products, so Johnson never had to concern himself with developing a business model or a marketing strategy.

Any business leader thinking about establishing a modern-day Skunk Works in their organisation would do well, then, to consider some key questions first. For instance, how would the firm separate radical innovation from business as usual and then integrate any outputs from the standalone R&D unit back into the central operation? And is there an inspiring leader with a proven record in the relevant field available in the organisation to take charge of such a unit?

Another important consideration is whether the company can foster an effective working relationship between that leader (Hayton uses the term “champion”) and the corporate leaders (“sponsors”).

“Just like Johnson was at Lockheed, the champion must be good at self-advocacy and be well connected across the broader enterprise,” Hayton argues. “The right person will have the ability to influence others and the social and emotional intelligence to understand how the whole organisation works. On the other hand, the sponsors must understand the nature of the risk they’re taking with a Skunk Works and its importance to the long-term health of the wider business.”

Then there’s the small matter of developing an agile culture inside the innovation unit. This can be aided by choosing the most appropriate people to work in it – those who enjoy operating with relative autonomy, for instance – and perhaps, as in the cold war, by giving them a specific goal and a tight schedule in which to achieve it.

The unit’s location is an important consideration too, especially if it requires more highly skilled people than the wider business has at its disposal, observes Andrew Gaule, CEO at innovation consultancy Aimava.

“If you’re seeking to innovate in oil exploration, for instance, you probably should be doing that in Houston or Aberdeen, because most of the experts are in those cities,” he says. “If you want to develop electric vehicles, your ideal site is more likely to be in Silicon Valley or Shenzhen.”

Gaule argues that any leadership team that’s tempted to establish a Skunk Works should treat it as one of a whole range of tools available to a company seeking to enable agile innovation. “You should also have a corporate venture team in place,” he says. “You should be investing in funds or managing a startup ecosystem and you should be encouraging innovation in your core business as well.”

One key lesson that businesses should learn from the Skunk Works model can be drawn more from the experiences of Johnson’s imitators, according to Criscuolo. “The general impression is that they fail,” she says. “But the problem is that failure is a necessary part of the process when you’re trying something new.”

For Martin, the most important insight he has taken from Johnson’s story and applied to Hyox is that every member of the leadership team must have the same attitude to innovation if the required hard-driving, agile culture is to be maintained. “That, more than any other factor”, he says, “is crucial.”

Smells like victory: what Skunk Works can teach us about extreme innovation

The remarkable feats of Lockheed’s elite warplane design team have inspired several corporate imitators. Are any of the rules set by its visionary creator in 1943 applicable in business today?

My very well received front page feature for Raconteur appeared in print on page 4 and 5 Enterprise Agility report tucked inside The Times newspaper.

You can find a screenshots of the article below – or click here for the full report.

(I will post the text shortly)

“Mark Piesing an incredible and insightful article on my hero Kelly Johnson. The Michigander that was described as “That damn Swede can see air”. I was honoured to have been interviewed by you Mark, and grateful to share our philosophy on radical innovation at Hyox Thank you again.”

“Great article by Mark Piesing about Kelly Johnson’s Skunk Works. Well balanced, and emphasises the importance of integrating the results into the parent organisation and especially the value of failure. And nice to be quoted

November 29, 2022

Fantastic news – My next feature for The Smithsonian’s Air and Space magazine has formally been accepted.

I have some great news!

I always wanted to write for The Smithsonian’s Air and Space magazine. Now my next article has just been accepted for publication. I can’t tell you what it is about, but I can say that it’s a long read, and it is about one of my favourite subjects.

Here again, is the first piece I wrote for Air and Space. I even dragged my wife, kids and dog around the New Forest looking for a forgotten WW2 airfield to research it.

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/air-space-magazine/across-channel-nazi-helicopter-180977810

Here is the second, where I tracked down and interviewed scientists-explorers who have flown drones in Antarctica and shared their experiences with me and their amazing photographs. It covered four double pages of the Air and Space magazine.

https://airandspace.si.edu/air-and-space-quarterly/fall-2022/remote-controlled

November 28, 2022

Author Interview – Mark Piesing – N-4 DOWN

It was great to be invited on to The Table Read to discuss my writing process and my first book N-4 DOWN.

Read my interview in full below, or the original here.

On The Table Read, “the best book magazine in the UK“, author Mark Piesing talks about his debut book, N-4 DOWN, and his writing process.

Written by JJ Barnes

I interviewed author Mark Piesing about his life and career, what inspired him to start writing, and the work that went into his debut book.

Tell me a bit about who you are.I am a freelance technology and aviation journalist and author. I live in Oxford.

Mark Piesing

Mark PiesingN-4 DOWN: the hunt for the Arctic airship is my first book.

When did you first WANT to write a book?As a child!

When did you take a step to start writing?I had a go at writing my first ‘book’ when I was 7 or 8, and I kept trying, even when I was back packing around India.

I remember writing rough notes for a book while travelling overnight in the back of a coach from the foothills of the Himalayas to New Delhi. Unfortunately, in the cold light of day what I wrote didn’t make much sense!

How long did it take you to complete your book from the first idea to release?It is hard to say as I came across the story of the crash of the airship Italia while writing a pitch for another book.

So, from when my agent, publisher and I had a call about the Italia story to completing the manuscript was about 22 months – but only about half of that was actual writing.

There was a deadline in my contract with the publisher – and that really helped to me focus!

What made you want to write N-4 DOWN?I love aviation, history, innovation, and exploration, and, so, when I discovered the story of the crash of the airship Italia near the North Pole, I just had to write it!

What were your biggest challenges with writing N-4 DOWN?That’s a good question! The biggest challenge I had was knowing how to start it, and then, how to tell it.

I was really stuck, and I was aware the contractual deadline was getting ever closer.

Then I flew up to Svalbard in the Arctic Circle, near where the airship crashed, saw this epic eternal landscape of brilliant white mountains and frozen sea, and realized that the story had to start here, and more than that, Svalbard itself must be a character in the story, which I hope I achieved.

What was your research process for N-4 DOWN?I read widely about the crash. Then I zeroed in on aspects of the story, such as the background of Umberto Nobile and Roald Amundsen, and explore that in more detail, particularly by reading eye-witness accounts, searching newspaper archives (which are now mostly online), travelling to locations in the book, such as the Arctic Circle for a sense of place, and looking for forgotten manuscripts, such as in an overlooked archive in Tromsø.

N-4 DOWN

N-4 DOWNI will never forget the feeling of holding a manuscript that Umberto Nobile had typed and then seeing his hand-written corrections on the side. I even tracked down one of the last people alive who knew Umberto Nobile, the protagonist, to a Copenhagen suburb.

How did you plan the structure of N-4 DOWN?The story told itself! I just followed the chronological order of events. I could add nothing to that!

Did you get support with editing, and how much editing did N-4 DOWN need?Yes. My editor at HarperCollins in New York took the time to do an old-fashioned line by line edit of my manuscript in pencil, and then DHL’d it back to me. I learned so much from reading his comments and seeing his changes.

The book published was the manuscript that was produced by that process; relatively little was changed after that.

What is the first piece of writing advice you would give to anyone inspired to write a book?That if they are serious about writing a book, then they need to write every day, even if it’s just a few lines.

Can you give me a hint about any further books you’re planning to write?I plan to write another gripping, thrilling book about men and women pushing technology to its limits in pursuit of high-stake goals.

And, finally, are your proud of your accomplishment? Was it worth the effort?Yes, I am. The great reception of the book from critics and readers has, for me, made it all worthwhile. But my wife may have a different view!

Pop all your book, website and social media links here so the readers can find you:Twitter @MarkPiesing

LinkedIn Mark Piesing

Instagram markpiesingwrites

Facebook Mark Piesing

N-4 DownOctober 24, 2022

7 facts you probably didn’t know about the most horrifying, gripping and disastrous Polar Expedition…

In this exclusive for Femalefirst, Mark Piesing reveals some amazing and shocking facts about his book N-4 Down. You will be enthralled, amazed and shocked – read on.

Writing this article for FemaleFirst about my book N-4 DOWN was great fun. It was a good excuse to ask readers what they thought the 7 facts should be.

Read the article in full below or the original by clicking on this link.

Listen to me talk about N-4 DOWN on BBC Radio here…

Roald Amundsen was perhaps the greatest polar explorer of all time. In 1905 he became the first man to successfully navigate his way through the Northwest Passage, the sea route from the Arctic to the Pacific Ocean. That heroic feat was surpassed six years later when he beat the British hero Robert Falcon Scott to the South Pole in 1911. Scott and his four companions died on the return journey.

In 1925, Amundsen – together with the American millionaire and coal magnate Lincoln Ellsworth – decided to fly to the North Pole in an airship. Italian engineer, Umberto Nobile, had the only airship in Europe suitable for the flight. Nobile didn’t look like the typical polar explorer. Born in the shadow of Vesuvius, near Naples in southern Italy, he was a descendant of one of the aristocratic families that had been close to the Bourbons, the ruling family of southern Italy. Nobile oozed a quiet confidence, bordering on cockiness. The engineer’s unravaged good looks and smart military uniform were evidence that he had spent many years with his wife and daughter in Italy, rather than alone on the polar frontiers. But, there was something else lurking behind his apparent confidence: fear. In 1923, 30,000 of Benito Mussolini’s Blackshirts marched on Rome and intimidated the Italian king, Victor Emmanuel III, into appointing their leader prime minister. Within three years, Mussolini made himself dictator, anointing himself ‘Il Duce’ – The Leader.

The Amundsen-Ellsworth-Nobile Expedition joined multiple engineers and explorers in the race to be the first to fly from Norway to the North Pole, across the shaded area on the map labelled ‘unexplored’, and then on to Alaska, in what the newspapers called ‘the most sensational sporting event in human history’. It was a competition that the Amundsen-Ellsworth-Nobile expedition won on May 14, when the airship Norge, designed, built, and piloted by the Italian, landed in Teller, Alaska. The New York Times headline read ‘NORGE SAFE IN ALASKA AFTER 71-HOUR FLIGHT’, devoting three pages to the story.

However, all was not well onboard the Norge. Tensions between Amundsen and Nobile exploded when the Norwegian realised that the thousands of Americans lining the quaysides and packing train stations were not cheering for the elderly explorer, but for the brave, good-looking Italian captain who had flown the craft: the man they were calling the ‘new Columbus’. It was a victory that made Nobile more of a target for his enemies in Rome, particularly for the Blackshirt’s leader Balbo. When he told Mussolini of his plans for a second flight, Il Duce warned him: “Perhaps it would be better not to tempt fate a second time.” Balbo requested two or three seaplanes as backup to help rescue the crew in case of a crash on the ice.

Nobile’s second exhibition was to take him to the North Pole on the airship Italia – code-named N. It launched on 23 May 1928 from Svalbard, 500 miles from the North Pole. The flight was to be the pinnacle of his career, certainly in the eyes of the world’s press. The sun glinted off the envelope of the airship as it rose majestically over the mountains and headed north, a vision to those on the ground of the future of Arctic exploration.

Fact No. 1: Half of the crew were never seen again

The Italia hit the ice at 10.33am on May 25 and, remarkably, it survived. Only the control cabin under the airship had smashed into the ice; the rest of the craft was still intact. Out of control, it slowly rose skyward. Nobile and the other survivors on the ice could make out the remaining crew staring down through the gaping hole where the cabin had been. The astonishment on their faces turned to horror as they realised their fate. The six men were never seen again.

Fact No. 2: Roald Amundsen’s death wish

Amundsen’s reply to the request on 26 May to look for Nobile was simple: “Tell them at once that I am ready.” It is hard to know why he so readily agreed to help, given their bitter, public falling-out. Of course, there were the rules of honour. And there was the glory. Perhaps it was the thought of a delicious final victory over Nobile, but there may have been a darker motivation too. Amundsen had recently had a cancer operation and needed radiation treatment. He sold off his collection of medals and honours and gave away his treasures. On the eve of his departure, Amundsen pointed at a model plane hanging from the ceiling and confessed, “That’s where I want to die, and I wish only that death will come to me chivalrously, will overtake me in the fulfilment of a high mission, quickly and without suffering”.

Fact No. 3: Amundsen died searching for Nobile

At 4:00pm on June 18, Amundsen’s plane raced across the harbour at Tromsø. It was seen by fishermen as it disappeared into a fog bank 40 miles out to sea. That evening two radio messages were received, including the mysterious, “Do not stop listening. Message forthcoming.” Whatever that message was, the operator never sent it. Later, a faint SOS was heard that may have been from Amundsen’s plane.

Fact No. 4: Umberto Nobile abandoned his men

Around 11.00pm on the evening of 23 June, Swedish pilot Lieutenant Einar Lundborg’s plane clattered across the ice. Dirty, unkempt, and sick-looking survivors ran to meet him.

“General, I have come to fetch you,” Lundborg told the badly injured Nobile. But Nobile refused to leave. Lundborg informed the general that he had orders to bring him back to co-ordinate the rescue operation. Nobile must have known that the departure of the commanding officer before his men was at odds with protocol and tradition. But he persuaded himself that it needed far more courage to go than to stay. “I am ready,” he said.

Fact No. 5: Nobile was betrayed by his government.

The moment Nobile was carried aboard the Italians’ base ship he realised that Lundborg had no orders to bring him back first. Injured, confused, and emotional from a month out on the ice, he made another mistake, giving in to pressure to write an apology to Mussolini. This note would be used by his enemies to prove his cowardice. The Fascists then built a prison around him. Armed police, seemingly posted outside his cabin to protect him, turned out to be wardens who had another job: to stop Nobile from leaving. His communication was restricted. He was barred from helping with the rescue operations and he was not allowed to see the newspapers, in which his own government defamed him.

Fact No. 6: Woman Joins Arctic Search

Nobile had been found, but Amundsen had disappeared. The search for the great explorer began to gain momentum. Then came the news that shocked the world: ‘Woman Joins Arctic Search’. Millionaire Louise Boyd’s luggage may have been designed for her by Louis Vuitton himself, but she was no stranger to the Arctic. Two years earlier, she made history when she became the first woman to organise, pay for, and lead an Arctic expedition. In the end, Boyd, like the rest of the would-be rescuers, found no trace of the old explorer, despite sailing for ten weeks in search of him. She became the first non-Norwegian national to be awarded Norway’s highest medal. Few clues as to Amundsen’s fate were found. One of the wing floats of his flying boat was recovered. Then, a fuel tank with a mysterious wooden bung in it. The search continues: expeditions using robotics still scour the seabed for Amundsen’s grave.

Fact No. 7: Cannibalism

At exactly 5:20pm on 11 July, the lookout shouted: ‘There they are!’ The crew of the Russian icebreaker Krassin thought they’d found the three survivors who, over a month earlier, had set off on foot to get help: Mariano, Zappi and Malmgren. But of Malmgren there was no sign. The medics feared Mariano wouldn’t live long; he was racked by fever, starvation, and frostbite. But his greatest fear had been that he would be killed and eaten. “When I die you can eat me, but not before,” he is reported to have said. On the other hand, Zappi was able to walk back to the ship unaided, and underneath his own sodden garments he appeared to be wearing Malmgren’s clothes. The press quickly picked up on the story. ‘Mystery about Malmgren’s body gives rise to reports of cannibalism,’ reported one newspaper.

The main wreckage of the Italia was never found. No expedition was launched to find them. The only clue to their fate was a column of black smoke that was seen for a while far to the north. In the wreckage of the control cabin, the only part of the airship to have smashed into the ice, the survivors found one of the mechanics bent double, as though tying his shoelace. When he didn’t respond, they shook him slightly. He toppled forward and rolled faceup. His face had been crushed by impact. He was dead.

Nobile’s decision to leave his men on the ice would destroy his career and haunt him for the rest of his life. No sign of Malmgren’s body has ever been found. Mussolini later agreed to pay his mother a pension. The suggestion by a Soviet scientist that Amundsen’s frozen body, if found, could be brought back to life, was fortunately never put to the test. In 2012, DNA tests were used to disprove two Inuit men’s claims that their father was Amundsen’s son. The remaining survivors of the Italia were rescued by the Soviet ice breaker Krassin three weeks later. Tragically, three more aviators who had joined the search for Nobile and his men died on their way home. Nobile and the seven other survivors returned to face Mussolini. Louise Boyd became respected as a serious scientist, leading four more expeditions to the Arctic. Like Amundsen, her nickname was ‘The Chief’.

During World War Two, Boyd would be sent on several secret missions for the US military in the Arctic. She would die penniless. Her fortune spent on exploration. Her ashes were scattered in the Arctic. The graves of the 14 dead crew members and their rescuers who died in the Arctic have never been found. Some believe that the melting ice caps will reveal their location.

About the author

Mark Piesing is a successful freelance technology and aviation journalist and author. He writes for brands such as BBC Future, The Guardian, Wired, and The Economist. Piesing is passionate about aviation, history, innovation, and exploration. His passion has led him to search for lost World War II airfields in the New Forest, find the last surviving Nazi helicopter, fly drones inside a fusion reactor (a world first), and tread carefully around Bosnian minefields. He has been driven by an autonomous car, flown in Britain’s flying laboratory, gone underground at CERN, and dug up the skeletons of gladiators in a lost Roman city in Spain. For Piesing’s first book, N-4 DOWN: The Hunt for the Arctic Airship Italia, he travelled to frozen Svalbard and the Arctic Circle, discovered forgotten manuscripts in an overlooked archive in Tromsø, and tracked down one of the last people alive who knew Umberto Nobile, the protagonist, to a Copenhagen suburb. Mark Piesing lives in Oxford, UK, with his wife, two children, and dog.

N-4 Down: The Hunt For The Arctic Airship Italia – By Mark Piesing

Genres: History, History of Arctic and Antarctica, History of Exploration, Aviation History, Aviation, History of Norway

Publisher: Mariner Books (imprint of Harper Collins) UK paperback publication date: 14/10/22

Availability: Paperback, eBook, Audiobook, International distribution ISBN: 9780062851536 Price £12.99

October 22, 2022

LISTEN to my BBC Radio interview HERE

Everyone loves a map in a book!

Everyone loves a map in a book! What a great idea! To mark the release of the N-4 DOWN paperback, BBC Radio Somerset’s Simon Parkin gave up an hour of his morning show to listeners sharing their airship stories on air before talking to me about my book N-4 DOWN the hunt for the Arctic airship Italia.

Simon then asked me some of the best questions I have ever been asked about my book!

Listen to my interview below

My interview with BBC Radio’s Simon ParkinFind out more about my book here

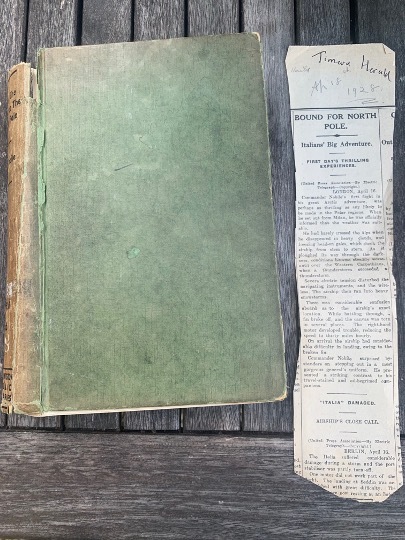

You see – they do exist! This the old book from 1930 I write about in the intro to N-4 DOWN along with the newspaper cutting from April 1928

You see – they do exist! This the old book from 1930 I write about in the intro to N-4 DOWN along with the newspaper cutting from April 1928

AIRSHIP’s great write up of N-4 DOWN

Thanks to Alan Shrimpton, Editor of AIRSHIP, for featuring N-4 DOWN.

For more information about

N-4 D DOWN click here

AIRSHIP and the Airship Association click here

October 21, 2022

My 5,000-word essay/ extract for US history magazine American Heritage: Italia Crashes In The Arctic

In 1928, an attempt to land the first men on the North Pole ended in tragedy when the airship Italia crashed, sparking the largest polar-rescue mission in history.

Read my 5,000-word essay/ extract about my book N-4 DOWN for the US history magazine American Heritage in full below or the original by clicking on this link.

Check out its historic photographs as well.

Editor’s Note: Mark Piesing is a freelance journalist and the author of N-4 DOWN: The Hunt for the Arctic Airship Italia, from which he adapted this essay.

“We are heavy,” the crewman shouted as the giant airship dropped through the fog toward the sea ice below. It was as if Thor himself were hurling the Italia out of the sky.

Perhaps the great explorer Roald Amundsen was right, thought General Umberto Nobile, leader of the expedition. The Italians were a “half-tropical breed” who did not belong in the Arctic.

Prodigy, dirigible engineer, aeronaut, Arctic explorer, opponent of Mussolini, maybe even a Soviet spy, and always accompanied by his Fox Terrier, Titina, Nobile twice flew jumbo-jet-size airships—lighter-than-air craft that he himself had designed and built—on the epic journey from Rome to Svalbard to explore the Arctic. The first was the Norge, which Nobile and his crew had successfully flown from Norway to Alaska in 1926 to become the first to overfly the North Pole.

The N-4 Italia was the second of these flying machines. “We are quite aware that our venture is difficult and dangerous…but it is this very difficulty and danger which attracts us,” said General Nobile in a speech to the wealthy and proud citizens of Milan on the eve of his departure in the Italia to Svalbard. “Had it been safe and easy, other people would have already preceded us.”

“We are quite aware that our venture is difficult and dangerous…but it is this very difficulty and danger which attracts us,” said General Nobile.

Two months later, General Umberto Nobile in his uniform marched across the snow and ice, and then along the side of the airship Italia as it floated a few feet off the frozen ground of Kings Bay, Svalbard. Its nose was attached to a tall mast that had been plunged into the permafrost two years earlier, and which still stands today. Nobile was forty-eight, but looked younger. This flight was to be the pinnacle of his career, certainly in the eyes of the world’s newspapers and newsreels—and that was, perhaps, all that he needed to be protected from his enemies in Rome.

As Nobile marched, he shouted instructions to his men, who labored in sub-zero temperatures to prepare the dirigible for its flight to the North Pole. Nearby, the coal miners from the Kings Bay Mine stood ready to provide the muscle power when needed. Journalists and photographers recorded the team’s every move. One of them caught the eye of the general and snapped a picture. The last one before he set off.

Behind Nobile and his men stood a strange-looking construction that dominated the bay. It had no roof, but there were two sides made from the type of wooden trestles that you see in Western movies, covered in green canvas held down by myriad guy ropes. One of the largest buildings of its kind in the world, it would protect Italia from the terrifying Arctic storms that could surely wreck it.

Designed by Nobile himself, the Italia—code-named N-4—was part of a wave of new airships that embodied the exuberant spirit of the early 20th century and opened up new frontiers of exploration. American Heritage Archives.

Designed by Nobile himself, the Italia—code-named N-4—was part of a wave of new airships that embodied the exuberant spirit of the early 20th century and opened up new frontiers of exploration. American Heritage Archives.Beautiful white mountains penned the Italian expedition in on three sides. The glaciers gleamed in the May sunlight. For a moment in the sun, the twenty-two houses of the mining village looked more like holiday cottages. “The Arctic smiles now, but behind the silent hills is death,” a journalist would later write, and he would be proved right.

Out in the bay, the sea was filled with great chunks of ice. Beyond stretched the endless ice pack, known as the Arctic desert, a huge empty hole on the map of the world and roughly the size of Canada. Somewhere on the other side was Alaska. Nobile’s mission was to claim any land he found in the name of fascist Italy.

Men on the ice quickly became invisible from the air in this brilliant white landscape. If their primitive flying machines quickly descended and they couldn’t get back up, then there was almost no likelihood that they would be found. Even if someone knew where they were, there would be a good chance that they had strayed beyond the range of their would-be rescuers, particularly if they were the crew of a dirigible like the Italia. These lighter-than-air craft could stay in the air for days at a time and fly much farther than their fixed-wing rivals.

To crash out there would in all likelihood mean death, though, surprisingly, this didn’t seem to bother the average adventurer.

The sea ice that makes up the ice pack was often many feet thick, and then suddenly only half an inch, ready to plunge the unwary—or too-hasty—explorer into the freezing water underneath. Night time might not bring much relief to the explorer, either. The cracking and creaking of the ice kept many a man from sleeping, no matter how exhausted they were, their bodies braced for the moment when they—and their tent—might suddenly be plunged into the freezing water below. Then there was the disorientation. When they woke up, they could be as many as twenty miles from where they had gone to sleep.

To crash out there would in all likelihood mean death, though, surprisingly, this didn’t seem to bother the average adventurer. This was their choice: to be noticed, to be remembered. Glory was what most of them had come here for—and one way or another, they were determined to get it.

Umberto Nobile didn’t look like the typical polar explorer. Born in the shadow of Vesuvius near Naples in southern Italy, he was a descendant of one of the aristocratic families that had been close to the Bourbons, the ruling family of southern Italy.

He oozed a quiet confidence—even cockiness. The engineer’s unravaged good looks and smart military uniform were evidence of his years spent with his wife and daughter in Italy, rather than alone on the polar frontiers.

Today, Nobile would be called a prodigy. In 1908, he graduated from the University of Milan with two diplomas: one in mechanical engineering and the other in electrical engineering. He went on to formally study the new science of aeronautics. In 1912, he finished at the top of his class.

Born near Naples in 1885, Umberto Nobile helped design airships both in Italy and the United States before undertaking his first Arctic explorations. Wikimedia

Born near Naples in 1885, Umberto Nobile helped design airships both in Italy and the United States before undertaking his first Arctic explorations. WikimediaBy December 1917, Nobile’s star was shining so brightly that he was appointed vice director of Stabilimento Militare di Costruzioni Aeronautiche (SCA). In July 1919, he became the director of the airship factory. He would go on to export airships to countries around the world from his sprawling empire of offices and factories centered on Ciampino, Rome’s second airport.

Two years later, the Roma, which he helped to design, was sold to the United States. The failure of its rudder when flying too fast and low over Norfolk, Virginia in February 1922 led to the Roma crashing into high-voltage power lines and exploding. Thirty-four of the forty-five passengers and crew were killed. The crash was the deadliest such disaster in US aviation history at the time.

The temptation must have been to blame the Italian designers for the crash, yet the fault seemed to lie closer to home. The US military had decided to save money by using flammable hydrogen in the airship, rather than the helium they knew was safer. The Americans had also replaced the Italian engines with more powerful American-built ones, with little thought as to the effects of such a retrofitting.

However, the Italian designers somehow seemed to escape blame, and Nobile’s stock remained high in the United States. The following year, he went to work as a consultant for the Goodyear Airship Corporation in Akron, Ohio—home in modern times of the famous Goodyear Blimp—on the construction of another airship. Announcing the collaboration, Aviation magazine described Nobile as the “foremost authority…in the world.”

In 1923, thirty thousand of Benito Mussolini’s Blackshirts marched on Rome and intimidated Victor Emmanuel III into appointing Mussolini prime minister. Within months, the Fascists had seized control of the machinery of government. Over the next three years, Mussolini dismantled the democratic structures of Italy. In October 1926, he felt secure enough to make himself dictator, giving himself the title “Il Duce.”

Like many educated people in the 1920s, Nobile would admire Mussolini for his ability to get things done. Indeed, his own ambition to explore the North Pole by airship would depend on Mussolini’s ability to do precisely that. Nobile was proud of his nation, had private audiences with the pope, and developed a good relationship with the king. Other than that, he never appeared to take much of an interest in politics. The fact that he didn’t openly support the Fascist Party appeared to be less a statement of belief than a sin of omission; however, it would soon leave him dangerously exposed in the knife-in-the-back politics of Mussolini’s Italy.

Fascist leader Italo Balbo was a different brand of villain from the jealous rivals Nobile had clashed with before. Balbo was a charismatic, street-fighting, cigar-chomping fascist leader. His “chestnut goatee, winning smile, and love of uniforms covered in gold braid and medals” may have made him a bit of a joke to some, but they disguised his ruthlessness and violent behavior. It was said that even Mussolini was scared of him.

Balbo wanted to rebuild the Italian air force around his ego and with two wings—and Colonel Umberto Nobile, his reputation and his airships, were in his way. So, when Balbo publicly declared, “There is no room for prima donnas in the Italian Air Force”— it seemed to Nobile like that was aimed at only one man, himself.

Nobile was an engineer and airman who lived under Mussolini’s regime, which worshipped aviation, and the men who flew these flying machines were portrayed as supermen.

Visitors to Nobile’s factory noted that there was a marked absence of posters of Mussolini on its walls. Egged on by Balbo, it wasn’t long before Nobile’s enemies spread rumors that he was a socialist whose factory was filled with “red laborers” and that he was even the leader of the anti-Fascist resistance.

However, Nobile was an engineer and airman who lived under Mussolini’s regime, which worshipped aviation, and the men who flew these flying machines were portrayed as supermen.

In 1925, the Norwegian polar explorer, Roald Amundsen, along with the American millionaire and coal magnate Lincoln Ellsworth, had wanted to fly to the North Pole in an airship, and Nobile had the only one in Europe that was suitable for the flight, and for sale.

The Amundsen-Ellsworth Expedition joined multiple engineers and explorers in the race to be the first to fly from Norway to the North Pole, across the shaded area on the map labeled “unexplored,” and on to Alaska, in what Polar Science Monthly called “the most sensational sporting event in human history.” The New York Timesdescribed it as “a massed attack on the Polar regions.”

If Amundsen thought he was only buying an airship and hiring a pilot, then he had another thing coming. Whether the Norwegian liked it or not, Nobile had the trump card in his hand — the airship — and the Italian rather liked the sound of the Amundsen-Ellsworth-Nobile Expedition. But a careful look reveals something else lurking behind Nobile’s apparent confidence: fear.

It is easy to imagine that, on the jotting paper on Nobile’s desk, one name was written down and underlined: Italo Balbo.

On May 23 at 4:30 a.m., just before launch, over 150 men held the Italia in place with guy ropes over the ice in Kings Bay, Svalbard. Journalists and photographers recorded the team’s every move. American Heritage Archives.

On May 23 at 4:30 a.m., just before launch, over 150 men held the Italia in place with guy ropes over the ice in Kings Bay, Svalbard. Journalists and photographers recorded the team’s every move. American Heritage Archives.Amundsen and his men were willing to take a gamble on the flight being a success. Their ethos was simply: “One set off — and hoped to come back.” If the airship crashed, they were ready to attempt an incredible feat of derring-do to get them out of trouble.

But for Nobile, the flight had to be a success. Any outcome that didn’t see the airship reach Alaska would be a failure for him, for his family, and for Fascist Italy. The guns would not be fired in salute if he had to trudge on foot to safety across the ice.

It was a competition that the Amundsen-Ellsworth-Nobile Expedition won on May 14, when the airship Norge, designed, built, and piloted by the Italian landed in Teller, Alaska. The New York Times headline read “NORGE SAFE IN ALASKA AFTER 71-HOUR FLIGHT,” and devoted three whole pages to the flight.

Two days earlier, the American, Norwegian, and Italian flags were dropped onto the ice at the North Pole. “Ours was the most beautiful,” one of the Italian crew recalled.

Later, Amundsen would bitterly mock the Italians and their flag. It was too big, he told everyone; it was a joke. The Italians could barely even organize themselves to throw the flag out of the cabin window. When they did, the thing was so large that it nearly fouled the ship’s engines and brought the dirigible down.

But for Nobile, the flight had to be a success. Any outcome that didn’t see the airship reach Alaska would be a failure for him, for his family, and for Fascist Italy.

The tensions between Amundsen and Nobile exploded when the Norwegian realized that the thousands of Americans lining quaysides and packing train stations were not cheering for the elderly explorer who had been a passenger on the flight, but for the brave, good-looking Italian airship captain who had flown the craft: the man they were calling the New Columbus.

An editorial in Aviation magazine claimed: “In the lighter-than-air [field], General Umberto Nobile has given Italy a rightful claim to leadership in the construction of medium-sized dirigibles. The Norge, which flew the Amundsen party over the North Pole, blazed a trail through the air from Europe to Alaska that will in the years to come rank with the first Northwest Passage as a historic event.”

It was a victory that made Nobile even more the target of Italo Balbo in Rome. No wonder, then, that Nobile decided to escape back to the Arctic almost as soon as he had landed in Teller.

When Nobile told Mussolini of his plans, Il Duce warned him: “Perhaps it would be better not to tempt Fate a second time,” but Balbo told Mussolini to “let him go, for he cannot possibly come back to bother us anymore.” Balbo seemed determined to make that prophecy come true when he turned down Nobile’s request for two or three seaplanes as backup to help rescue the crew in case of a crash on the ice.

Roald Amundsen, the famed Norwegian explorer who had joined Nobile on their first airship expedition to the Arctic in 1926, organized the first rescue mission to find survivors of the Italia crash. Tragically, Amundsen and his crew of five themselves disappeared en route, never to be seen again.

Roald Amundsen, the famed Norwegian explorer who had joined Nobile on their first airship expedition to the Arctic in 1926, organized the first rescue mission to find survivors of the Italia crash. Tragically, Amundsen and his crew of five themselves disappeared en route, never to be seen again.In May 1928, the weather seemed to be against Nobile. He was facing rising temperatures, which could compromise the airship’s lifting power because of the expanding hydrogen. In addition, the summer fogs made flying especially hazardous. He started to think the unthinkable — of postponing the flights to the fall, when the temperature would drop again — if, that is, Balbo allowed him to.

However, on May 22, a high-pressure system covered Greenland with colder-than-expected air, a blessing since their planned route to the North Pole would take the airship over the massive island. But there was — of course — a caveat. The Tromsø Institute warned that the “favorable situation [was] not likely to last much longer, because the warm currents [would] give rise to the formation of fog.”

It was 4:30 a.m. on May 23, and more than 150 men were holding the guy ropes that kept the giant airship a prisoner, floating just above their heads. The chaplain, Father Franceschi, offered one last prayer. Nobile shouted, “Let’s go!” The ground crew let go of their ropes with a chorused “Hurrah!” The engines roared to life, and the N-4 Italia lifted off, disturbing a flock of gulls that rose screaming into the sky.

The sun was glinting off the envelope as the airship rose majestically over the mountains and headed north. To many of the men, it was a vision of the future of Arctic exploration. “A shimmering silver shape, glinting far above the ice hummocks and dimly seen from below,” one journalist wrote. “How different from those labored tours of old, when sledge parties left their floe-hemmed craft to toil among the ridges in the white glare of the Arctic.”

The weather report had been as good as it was going to get—but how many times since they had left Milan had the men on the Italia heard that? By the afternoon, the thin layer of dense fog that had accompanied them from Kings Bay out toward Greenland started to turn into something more worrying—a wall of fog. The unbroken white-out wrapped the airship, preventing the navigators from taking their bearings in this featureless landscape.

Finally, at 5:30 p.m., the fog cleared enough that they were able to identify Cape Bridgman on the north coast of Greenland, the point at which they would turn and head straight for the North Pole. Fortuitously, a strong wind suddenly picked up and blew them in the direction of the pole.

But the wind was a mixed blessing. While it meant that the flight to the pole could take a very fast twenty hours because of the assist, the N-4 would be fighting every inch of the way back against a strong headwind. This taxing battle, Nobile calculated, could take forty hours and perhaps every drop of fuel they had, because the irregular zigzag pattern they would have to fly would involve many more miles than the straight-line distance back to Kings Bay, as well as exhausting the helmsman who had to manually steer the ship.

The unbroken white-out wrapped the airship, preventing the navigators from taking their bearings in this featureless landscape.

Nobile spread the maps out on the table in the cramped cabin. He had another plan: to just keep cruising beyond the pole, bearing east to land at Mackenzie Bay in northwestern Canada—a route that he knew well, having flown it successfully in the Norge. He had even made sure that the charts for that eventuality were stowed on board. Nobile asked Finn Malmgren, the ship’s Swedish weatherman and one of two non-Italians on the crew, for his advice. “Better to return to Kings Bay,” he responded. “Then we can complete our research program.”

Nobile also wanted to return to Kings Bay. If they headed for Canada, it would all be over because it would be a one-way flight. Without an airship mast or a big-enough hangar, the Italia would suffer the same fate as the Norge. It would have to be deflated the moment it landed.

But still, he hesitated. He didn’t want to put his men and ship through another exhausting battle against headwinds, as they had experienced on the previous flights. Maybe they could fly around the storm to Severnaya Zemlya off the Siberian coast and then back to Kings Bay. “This was truly a venturesome and attractive plan,” he wrote. But Malmgren was “adamant” that the direct flight home was the best option.

Nobile’s Italia crew consisted of several Italians and two foreigners, including Finn Malmgren, a Swedish weatherman who wrongly predicted that the ship would clear the fierce storm that ultimately caused the crash. American Heritage Archives.

Nobile’s Italia crew consisted of several Italians and two foreigners, including Finn Malmgren, a Swedish weatherman who wrongly predicted that the ship would clear the fierce storm that ultimately caused the crash. American Heritage Archives.Malmgren finally got his way when he convinced Nobile that the winds would die down. “This wind won’t last,” he said confidently. “It’ll drop a few hours after we have left the pole, and then it’ll be succeeded by more favorable winds, from the northwest.”

There was only one problem. Malmgren was wrong.

At 10:00 p.m. along the horizon lay a wall of cloud 3,300 feet (1,000m) high, as if “walls of some gigantic fortress,” Nobile imagined, had formed to defend the North Pole against the aviators. Somehow, they broke through it.

At 12:24 a.m. on May 24, the cry went up: “We are here!” Nobile ordered the engines slowed and the helmsman to circle the pole.

They were now directly over geographical zero. He had done it. He had proved Amundsen wrong. The Italians could conquer the Arctic.

Slowly, the huge airship circled lower and lower, until they could see the tortured, fractured, and jumbled surface of the ice pack below them.

He had done it. He had proved Amundsen wrong. The Italians could conquer the Arctic.

There was a moment of disappointment when the crew could not land a party on the ice because the wind was too strong for the “sky anchor” to hold the airship steady. Nevertheless, in “religious silence,” the men made ready to complete “the solemn” duty entrusted to them by Pope Pius: at 450 feet (140m), they dropped the Italian flag, the Tricolore, onto the summit of the world, followed by the flag of the city of Milan, and, finally, the cross that the pontiff had presented to them. “And like all crosses,” the pope had said with a sad smile during their last audience, “this one will be heavy to carry.”

With their jobs done, the gramophone player on the airship belted out the martial notes of the Fascist Party hymn, “Giovinezza,” Italy’s unofficial national anthem. With their right arms raised in the fascist salute, the crew sang along heartily under the watchful eyes of a journalist from Mussolini’s own newspaper, while Nobile looked on.

The singing rapidly gave way to the cry of “Viva Nobile” and a toast of eggnog. Nobile had been here before, but this time, it felt very different – almost as if it were the first time.

The Detroit Free Press headline read “NOBILE CRUISES OVER POLE… STARTS BACK…REACHES TOP OF WORLD SECOND TIME.”

At 2.20 am on May 24, the Italia left the North Pole, flying directly to Kings Bay in the face of the very strong winds that Malmgren had convinced Nobile would clear.

Five hours later, the ship was in a battle for its life. The fog was thick and gray. There was no sunlight. The wind whistled through every crack in the canvas-walled cabin. The metal structure of the ship creaked as if in agony. Its engines were roaring just to keep it inching forward. What sounded like bullet shots from the ice breaking off the propellers made the exhausted men hold their breath, the cold cutting through their heavy lambswool clothing. (Nobile was still in his uniform with the wool sweater that he wore over it because it enabled him to move quickly.)

“Each man went about his work in silence,” wrote Nobile. “The vivacity and cheerfulness that had accompanied our outward journey had now disappeared.” Everyone knew that the fuel was running out.

The ship suddenly felt very small. If the men wanted a chance to get any sleep, they had to bed down in the gangway in the keel. There had been too little rest between the long, demanding Arctic flights they had already undertaken.

By 7:30 a.m. on May 25, they should have been able to see the mountains of Svalbard, but they couldn’t. “I was anxiously watching for the northern coast of Svalbard to loom up in front of us,” Nobile recalled, “and instead, every time I looked out of the portal, I saw nothing but the fog and ice.”

Nobile had been awake for more than seventy-two hours in the noise and cold of the airship, and, by now, his ability to think straight must have been severely limited.

It was then that he couldn’t hide his fears anymore. The crew who knew him could see it in the lines on his face. (The radio operator, Biagi, told the ship at Kings Bay: “If I don’t answer, I will have good reason.”)

This was hardly surprising. Nobile hadn’t slept for days. His lack of sleep was on top of three other exhausting flights in quick succession. He needed a rest, but he was trapped by his culture’s, and his own, sense of what good leadership was all about, by his belief that another pilot would not make the quick decisions he needed to make in an emergency, and by the fear that he could empower an ambitious rival. Without a second-in-command, there was no one who had the courage to tell him to get some rest.

His brain was stuck in slow motion just when events were speeding up. Nobile was so tired that he was hallucinating. In the picture that hung on the wall of the cabin, his daughter, Maria, now looked as though she were crying. He had to tell himself that it was just the condensation on the inside of the glass.

At 9:25 a.m., there was a loud bang, and Nobile heard the cry, “The elevator wheel has jammed!” The controls of the helm were locked, pointing the Italia downward, and at an altitude of 750 feet (230m), it was hurtling toward the ice—and destruction.

With the engines roaring, the lives of the sixteen men on the airship hung in the balance. Nobile had been awake for more than seventy-two hours in the noise and cold of the airship, and, by now, his ability to think straight must have been severely limited.

“All engines, stop!” Nobile cried above the roar of the wind. It was the only thing he could do. With the engines off, the wind should slow the descent of the airship and eventually lift it up again on its currents, away from the pack ice.

Then, at 300 feet (90m), the ship started to ascend again—and quickly. Then Nobile, his brain starved of sleep, made a questionable decision: he let the airship continue to rise and, as a precaution, vented off some of the precious hydrogen that they might later desperately need for extra lift. He could have chosen to restart the engines instead to slow the zeppelin’s ascent.

“The Arctic smiles now, but behind the silent hills is death,” a journalist wrote shortly after the Italia’s departure. He would be proved right. American Heritage Archives.

“The Arctic smiles now, but behind the silent hills is death,” a journalist wrote shortly after the Italia’s departure. He would be proved right. American Heritage Archives.At 3,000 feet (900m), “glorious sunlight” flooded the cabin, lifting the spirits of the crew—but not for long. The sun’s rays would quickly start to heat up the hydrogen in the gas cells, and if the airship stayed too long in the sun, it would become superheated and be automatically vented off to prevent the airship from bursting. There was a real danger that the Italia would then plummet to the ground when it descended because, as the outside temperature dropped, the gas would condense, leaving it without enough lift.

Uncharacteristically for Nobile, who was keenly aware of the danger, he decided to keep the Italia in the direct sunlight for thirty minutes. He could now use the sextant to work out their location and could also finish repairs to the damaged control surfaces, but this was another dangerous move.

With the repairs complete, around 9:55 a.m., Nobile ordered the engines started up again, but he hesitated for a moment, letting the N-4 sail on without power, hoping that he would see the peaks of Svalbard. But there was no sign of home. All he could see was the freezing fog.

The captain had no choice but to let the Italia descend again into the cloud. At 1,000 feet (300m), the storm had cleared enough for the men to see the ice pack every now and then. The wind dropped, just as Malmgren had predicted. The airship was making a decent 30 mph. Nobile even started to think about his bed at Kings Bay.

But the gods were just toying with them.

At 10:30 a.m., the tail of the ship had almost imperceptibly begun to drop. The cry went out: “We are heavy!”

The ship was listing to stern and falling at a rate of about two feet (0.5 m) per second. The earlier release of hydrogen may have condemned the dirigible.

At 10:30 a.m., the tail of the ship had almost imperceptibly begun to drop. The cry went out: “We are heavy!”

Nobile was shocked. He struggled to explain what was happening. The bow was pointing upward, but the ship was falling. It was against the laws of physics.

There was now only one thing he could do. “All engines. Emergency. Ahead at full!” he shouted. But, according to his instruments, the increase in speed had no effect.

To try to gain altitude quickly, he screamed, “Up elevators!” But that only made things worse. The bow was tilted so high that, if he wasn’t careful, the ship would stall, making its destruction certain.

“She’s still heavy, General!” he was warned, but the situation was obvious to everyone who was awake. Incredibly, some of the crew had been so exhausted that they were still asleep in the tail.

After the crash, crew members of the Italia erected a tent on an ice floe that could be seen by rescue planes from the sky. One of those was a Savoia hydroplane operated by the Italian pilot Maddalena, who snapped a rare photo of the tent during one of his searches. American Heritage Archives.

After the crash, crew members of the Italia erected a tent on an ice floe that could be seen by rescue planes from the sky. One of those was a Savoia hydroplane operated by the Italian pilot Maddalena, who snapped a rare photo of the tent during one of his searches. American Heritage Archives.Nobile must have suddenly realized that what had seemed inexplicable could be explained if one of the valves had frozen open and hydrogen was pouring out. He ordered one of his men to “run aloft and check one of the stern valves.” But they were reported to be in order—and Nobile had himself modified them to protect them from ice before they had left Italy.

There may have been a tear in the envelope of the airship, or ice may have covered the ship as it descended, but the problem was that they were out of time.

“Look! There is the ice pack!” warned Malmgren, his knuckles white as he fought with the steering wheel to turn the airship away from disaster.

Nobile’s eyes were fixed on the variometer. He knew from the rate of descent that they were going to crash. The engines were on full power. The nose of the airship was up at twenty-one degrees and, still, the ice was rushing toward them.

“Stop all engines! Close all ignitions!” he shouted. All they could do was try to prevent the spark plugs in the engine from igniting all the hydrogen in the huge envelope above them if they crashed. The danger that the airship would go up like a Roman candle on impact had haunted all dirigiblists.

“The elevators have lost all response! The wheel is dead!” shouted Filippo Zappi, one of the navigators with significant experience on airships.

“God save us!” were the last words Nobile uttered. The last thing he heard was the snap of his leg bone. His last thought: “It’s all over now!”

Nobile ordered the sky anchor deployed to slow their landing. It had worked at Teller with the Norge, and it should work here. But it didn’t; the cabin was at such an angle that the men couldn’t reach the hatch to deploy it.

There were 100 feet (30m) to go, and they were clearly going to hit the ice too fast—ice that was jagged, not smooth, as it had looked from higher up. There wasn’t even a layer of snow to cushion the impact. And they were going to hit tail-first.

“This is the end,” said Professor František Běhounekto, one of the two scientists on the flight.

“God save us!” were the last words Nobile uttered. The last thing he heard was the snap of his leg bone. His last thought: “It’s all over now!”

Amundsen’s flying boat left Tromsø at 4:00 pm on June 17, almost a month after the Italia crash. It was last seen by fishermen two hours later, out at sea, about forty miles from land.

Amundsen’s flying boat left Tromsø at 4:00 pm on June 17, almost a month after the Italia crash. It was last seen by fishermen two hours later, out at sea, about forty miles from land.It was 10:33 a.m. on May 25.

Today, Dronningen Restaurant can be found on the shore of Oslofjord, as it has been for a hundred years. The white sails of the yachts are still seen out on the water. The only significant difference in the surroundings today is the modernist design of the current incarnation of the restaurant.

In 1928, the Dronningen was housed in a traditional, slatted, wooden, two-story clubhouse with a veranda and a lookout perched on its roof. Its diners were a favorite subject for the brushes of local artists.

At the restaurant on May 26 were many of Norway’s top explorers, men such as Otto Sverdrup, Oscar Wisting, Gunnar Isachsen, and Roald Amundsen. They had been brought together by the Norwegian newspaper Aftenposten for a dinner to celebrate the April flight of George Hubert Wilkins and his co-pilot, Captain Carl Ben Eielson, from Point Barrow in Alaska to Green Bay, Svalbard, a success that highlighted the struggle of Nobile’s airship to make it to Kings Bay.

The mood turned dark. What could possibly have happened to the Italia? Could it still be in the air? Where could it have crashed?

The men were looking forward to their rich meal of broth with beef marrow, smoked salmon, spinach and scrambled eggs, lamb saddle, cheesecake, and parfait. Barely had they raised their forks to their mouths when a telegram boy rushed in with a message from the paper’s correspondent on Svalbard: the Italia had not returned from the North Pole.

The mood turned dark. What could possibly have happened to the Italia? Could it still be in the air? Where could it have crashed? How would the Italians cope on the ice floe? The celebration of Wilkins and Eielson’s triumph was forgotten because of Nobile’s crash. The same sentiment was felt across Europe.

A few minutes later, one of the waiters rushed up to tell the editor of the Aftenposten that the defense minister wanted to speak with him. The editor returned with the news that the explorers needed to go straight to the ministry to plan a mission to look for Umberto Nobile and the crew of the Italia.

The room went quiet. Everyone looked at Amundsen.

There wasn’t a single diner in the room who didn’t remember the bitter quarrel between him and Nobile.

The great explorer’s reply was simple: “Tell them at once that I am ready.”

Where the Italia had hit the ice pack at 10:33 a.m. on May 25 looked like the crash site of any other aircraft, but with one big difference: the airship had survived.

Amudsen’s flying boat was only one of the aircraft sent out in search of the Italia’s crew. Others included Maddelena’s Savoia hydroplane, the ski-equipped DeHavilland Moth piloted by a Swede named Schyberg, and the Fokker biplane piloted by Einar Lundborg, which itself crash-landed on an ice floe while attempting to rescue the stranded survivors. American Heritage Archives.

Amudsen’s flying boat was only one of the aircraft sent out in search of the Italia’s crew. Others included Maddelena’s Savoia hydroplane, the ski-equipped DeHavilland Moth piloted by a Swede named Schyberg, and the Fokker biplane piloted by Einar Lundborg, which itself crash-landed on an ice floe while attempting to rescue the stranded survivors. American Heritage Archives.It was only the control cabin under the airship and the stern engine that had smashed into the snow and ice. The rest of the airship was still—more or less—intact, and the huge envelope of the airship still filled the sky above the crash site; on its side, ITALIA was visible in big black capitals.

Free of human control, the airship slowly rose skyward into the bank of fog like the balloon it had now become, its prow pointing up as if it were taking off again, which in a way it was. Two of the three engines were still in place, though useless.

The six men trapped in the envelope of the N-4 when it crashed were never seen again. The wreckage was never found. No expedition was launched to find them. The only clue as to their ultimate fate may have been a column of black smoke that was seen for a while far to the north.

The six men trapped in the envelope of the N-4 when it crashed were never seen again. The wreckage was never found.

The survivors found one of the mechanics in the wreckage like he was bending over to retie his shoelace. When he didn’t respond, they shook him slightly. He toppled forward and rolled faceup. His face was blackened, crushed by impact. He was dead.

At 4:00 p.m. on June 17, Roald Amundsen’s flying boat taxied across the water at Tromsø. As it raced across the still, calm water of the harbor, it was clear it was struggling to take off. But at last, the plane ascended.

The plane carrying Amundsen and five crew was last seen by fishermen two hours later, out at sea, about forty miles from land, flying into a huge fog bank. It was never seen again.

Six days later, just after 11 p.m. on June 23, a small Swedish plane managed to land on the floating sea ice next to the survivors. The leader of the expedition, the badly injured General Umberto Nobile, was persuaded to break the law of the sea to become the first survivor to be rescued, along with Titina, his Fox Terrier. If Nobile had known how his enemies would use this decision against him, he might have taken a stronger stance against leaving his men behind.

[image error]On July 12, 1928, seven weeks after the crash, the Russian ice-breaker Krassin rescued the last five survivors of the Italia. The graves of the 14 dead dirigiblists and their rescuers who died in the Arctic have never been found. WikimediaThe rest of the survivors, bar one man, were rescued by the Soviet ice breaker Krassin three weeks later. Of Finn Malmgren, there was no sign. His fate, best not to contemplate. Time magazine asked: “Was that Swede really eaten by those Italians?”

Time magazine asked: “Was that Swede really eaten by those Italians?”

Tragically, three more aviators who had joined in the search for Nobile and his men died flying home.