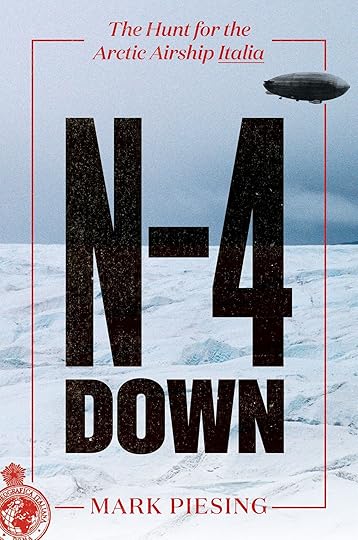

Mark Piesing's Blog, page 12

September 9, 2021

The Wall Street Journal…‘N-4 Down’ Review: Above the Ice

I don’t think I will ever forget to wake up to discover that my first book N-4 DOWN had been reviewed by The Wall Street Journal in print, in a very prominent position in the paper, online.

Then a couple of days later The Wall Street Journal Books newsletter recommended it as well.

Read the review of N-4 DOWN in full below, or by clicking on this link. Buy the book here.

On May 24, 1928, Gen. Umberto Nobile and his crew aboard the airship Italia—code-named N-4—dropped Italian flags and a small wooden cross given them by Pope Pius XI onto the North Pole from 450 feet in the sky. Airships were a technological marvel of the early 20th century, and the Italia’s goal was to land men at the North Pole, something that had never been done before. But bad weather thwarted the mission; returning to its base on Norway’s Svalbard archipelago, the Italia crashed into the ice, triggering one of the greatest polar rescue efforts ever mounted, a saga that journalist Mark Piesing retells in “N-4 Down: The Hunt for the Arctic Airship Italia.”

Until the so-called machine age, attempts to penetrate the Arctic’s nearly 6 million square miles of frozen seas had depended on surface vessels. As Mr. Piesing notes, planes and airships changed everything, a fact not lost on Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen, the victor of the 1911 race to the South Pole. In 1915, Amundsen obtained Norway’s first civilian pilot’s licence. Ten years later, after numerous failed attempts to reach the North Pole via plane, he approached Umberto Nobile, an Italian air-force officer who had designed a prototype airship and had ambitions of his own to fly to the North Pole.

Italy’s dictator Mussolini agreed to sell the N-1, as Nobile’s airship was called, to Norway. Though the ship was renamed the Norge, for “Norway,” Nobile would pilot the craft, and six of the 16 crewmen would be Italian. From the outset, personal rivalries between Amundsen and Nobile tainted the venture, which was nonetheless a success. In May 1926, the Norge flew from Svalbard over the North Pole and landed in Alaska. Nobile enjoyed and exploited his new celebrity. An aggrieved Amundsen convinced that Nobile was seizing all the glory for himself, announced his retirement from exploration.

Nobile, Mr. Piesing relates, almost immediately began planning another Arctic expedition, undaunted by Mussolini’s lack of enthusiasm or the jealousy of Italo Balbo, the head of the Italian air force, who viewed Nobile as a rival yet allowed him to use the N-4, another airship that Nobile had designed. Among the Arctic flights that Nobile planned, again from Svalbard, was one to the North Pole, where this time he hoped to land men.

The Italia left Svalbard on May 23, 1928, and early the following day reached the North Pole. The jubilant crew members celebrated by toasting one another with eggnog and playing the Italian Fascist Party anthem on a gramophone. High winds prevented a landing, so Nobile set course back to Svalbard. The wind slowed the Italia on its return, and at one point the helm controls jammed. Freezing fog, meanwhile, prevented Nobile from calculating his position accurately. Even more seriously, the airship began icing up. The crew lost its battle to stay airborne, and the Italia plunged onto the ice, tail first.

The control cabin detached on impact, flinging out 10 men, including Nobile, who broke an arm and a leg. One man was killed instantly. Now much lighter, what was left of the airship simply floated away. The six crewmen still aboard the Italia were never seen again, but one had sufficient presence of mind to throw out food and equipment, including a tent, a pistol and a portable radio, to his colleagues below.

The survivors painted their single tent red to make it more visible from the air and radioed desperate SOS messages that they feared no one was receiving. But rescue plans were in fact under way. Among the searchers, despite his hostility to Nobile, was Amundsen, whose plane disappeared on the quest and whose body was never found. After four miserable weeks, help finally reached Nobile when a Swedish pilot landed his small plane judderingly on the ice. Nobile had not intended to leave his men, but the pilot insisted that his orders were to evacuate him first to help coordinate the rescue of the others, and so he agreed. The Soviet ice-breaker Krassin eventually rescued the remaining survivors from the camp, along with two crewmen who had set out across the ice.

Back in Italy, Nobile found himself out of favor with Mussolini, who, encouraged by Balbo, regarded the Italia’s loss as a national embarrassment. Nobile was accused of abandoning his men, even though he believed he had been obeying orders, and an official inquiry condemned his actions.

Mr. Piesing writes with obvious enthusiasm for his subject. His depictions of airship flight are gripping, whether he’s discussing the Norge’s 1926 journey over an icy wasteland traversed by Arctic foxes and polar bears or the doomed Italia’s final hours. But the author’s foreshadowing of events and extraneous digressions sometimes diminish the drama and slow the pace of the narrative. Details of how Norway’s Oscarsborg Fortress delayed the Nazi invasion in 1940, and of the building of the Viking Ship Museum, distract from the central story of the Italia, which does not begin until nearly halfway through the book.

There are also omissions. Mr. Piesing refers to Fridtjof Nansen as Amundsen’s “great nemesis” without explaining Nansen’s huge influence on Arctic exploration or the complex relationship between the two men. (Nansen advised Amundsen and lent him his ship Fram.) Neither does he develop the characters of Amundsen and Nobile as fully as he might. A comparison of Nobile’s management of stranded men with that of Ernest Shackleton’s 13 years earlier on the Endurance expedition in Antarctica, in even greater isolation, would have been illuminating and relevant.

Nevertheless, this is a book with much to enjoy and a good illustration of what human curiosity, determination and courage—and sometimes a healthy dollop of vanity—can achieve.

Ms. Preston is a historian who has written on the race for the South Pole. Her latest book is “Eight Days at Yalta: How Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin Shaped the Post-War World.”

Copyright ©2021 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8

Appeared in the August 18, 2021, print edition as ‘Above The Ice.’

The review of N-4 DOWN as it looked on the page

The review of N-4 DOWN as it looked on the page

September 8, 2021

The planes that conquered Antarctica

Flying on the coldest continent on Earth is a dangerous business, but without aircraft we would still know relatively little about Antarctica and life there would be impossible.

Read my latest piece for BBC Future in full below, or by clicking on this link.

The heroic age of Antarctic exploration reached its zenith in December 1911, when Norwegian Roald Amundsen beat Robert Falcon Scott to the South Pole. It ended, arguably, at 8.20am on 20 December 1928, when Australian Sir George Hubert Wilkins took off in a “sleek, shiny, bullet-shaped” high-wing monoplane from Deception Island, just off the Antarctic Peninsula, to explore the last great hole in the map.

With that flight, the machine age of Antarctic exploration had definitively arrived – the flying-machine age – and arguably, we are still in it nearly a century later. There are around 50 runways in Antarctica, and Australia is hoping to build a new concrete runway.

Wilkins’s flight was followed by similar flights by early aerial pioneers such as Richard Byrd, aviators divided by feuds but who were as brave as their muscle-powered predecessors. Their expeditions paved the way to the demilitarised, environmentally protected, and science-led Antarctica we have today, even if it is, perhaps, not the one they wanted.

“The pioneers like Wilkins were hugely courageous aviators,” says Victoria Auld, a pilot with the British Antarctic Survey (BAS). “We have GPS and radio, but they would set out on long flights to the pole with only a sextant to estimate their positions with, and a lack of, even basic communications equipment.”

Like elsewhere in the world, even in the early days of Antarctic aviation, aircraft completely transformed what explorers were able to achieve.

“The plane was the real game changer because you can cover so much ground so quickly,” says Klaus Dodds, professor of geopolitics at the University of London Royal Holloway, and author of The Antarctic: A Very Short Introduction.

But aircraft also gave explorers an entirely new perspective on the Antarctic continent that allowed them to see just how vast it really was.

“Wilkins and Byrd were the first people to systematically fly over Antarctica,” says Adrian Howkins, a reader in environmental history at the University of Bristol. “When you look at the maps they produced you can see just how much of the continent they were able to see from a plane, rather than a ship or walking across the ice. But making sense of what they saw wasn’t as easy and some mistakes were made.”

Hubert Wilkins’ Antarctic flights marked a new era of exploration on the continent, although many of his findings were later shown to be inaccurate (Credit: Bettmann/Getty Images)

Antarctica may now have been mapped by satellites, but it doesn’t mean that humans have been everywhere, or that the maps have always been updated. “Sometimes mountains would be marked on the very basic maps that we had,” says polar explorer Felicity Aston, a former BAS meteorologist, author, expedition leader and, in 2012, the first woman to ski alone across Antarctica. “Sometimes they wouldn’t be, and suddenly you were flying over a whole mountain range when on the map there was a bit of text in the middle of a large, blank white area, that said, mountain spotted here in 1967.”

Auld now flies the high-wing, twin-engine de Havilland Twin Otter. The Twin Otter is a mainstay of the BAS “air force” because of its toughness, reliability, and ability to take off from, and land on, short runways.

Typically, she is “flying survey lines” above a particular spot to investigate geophysics or atmospherics in that location, or on week-long trips to instrument sites in the “deep field” to download data, carry out repairs and set up new instruments.

“Some of the older guys would say there is no more real flying these days,” says Auld. “But there’s not many jobs, certainly for a UK pilot, where you can go and land on snow on skis in an aircraft.

One of the greatest dangers pilots face in Antarctica is disorientation due to a lack of contrast between the sky and the land. To prevent this danger, BAS won’t deploy an aircraft to a new site unless there is “sunshine on the ground” [clear blue sky].

“When we go deep field into mountain sites, we’ll have a good look at the landing site from overhead from many different angles to spot crevices,” says Auld. “Then assuming we can’t find any, we use a technique called trailing ski to put sufficient weight on the skis to test to see how rough the surface is, but also to see if we’re exposing any crevices that we couldn’t see from the air. If we’re happy with that, then we’ll come in and land.”

In Antarctica it pays to think about the what ifs. “We are always thinking about our go-around pattern and making sure we’re not exposing ourselves to a situation where you can’t get away because of rising ground ahead of you,” she adds.

Auld finds herself talking increasingly with drone pilots, working out how to blend operations of the Twin Otter with the Remote Piloted Aircraft Systems (RPAS) that the BAS is developing.

After nearly 4.5 hours, with half his fuel spent, Wilkins opened a hatch, dropped a proclamation claiming the land for King George V of Great BritainIn 1928, the bullet-shaped aircraft that Wilkins and his co-pilot Carl Ben Eielson flew was the cutting-edge craft of its day. Their Lockheed Vega was designed by Jack Northrop, who later founded the Northrop Corporation, famous for the B-2 Stealth Bomber. Earlier in the year, in another Vega, the two pilots had become the first to cross the Arctic Ocean from Alaska to Svalbard, Norway.

On the opposite side of the world, the explorers raced above the Antarctic Peninsula. In just 20 minutes, the Vega covered 40 miles (65km), a distance that would have taken months to traverse on foot. After nearly 4.5 hours, with half his fuel spent, Wilkins opened a hatch, dropped a proclamation (a flag and document) claiming the land for King George V of Great Britain, and reluctantly turned back.

In the 10-hour flight – filmed by two movie cameras on board – the Australian and his American colleague had crossed at least 1,000 miles (1,600km) of previously unrecorded Antarctic territory. During the flight they were able to get a view over 100,000sq miles (258,998sq km) of Antarctica, according to estimates from the time. Wilkins named the bays, land and mountains he discovered after his supporters: Hearst Land, Mobiloil Inlet and Lockheed Mountains. “For the first time in history, new land was being discovered in the air,” he wrote.

From his flight, Wilkins mistakenly concluded that the Antarctic peninsula was three islands rather than an extension of the mainland.

You might also like:

The icy village where you need surgery to liveHow flying messes with your mindThe frozen graveyard at the bottom of the worldBut the Australian soon had company in Antarctica. In January 1929, American explorer Richard Byrd’s “million-dollar expedition” had arrived in the Bay of Whales, near Scott’s base for his ill-fated expedition. This was the largest expedition yet sent to Antarctica, and with it came three aircraft and the men to build an underground base in which to overwinter. It was named Little America, and three radio antennae marked its spot. A large slice of Western Antarctica was named after Byrd’s wife, Marie Byrd Land.

Wilkins’s arctic flight had been a triumph, but many doubted that Byrd had flown to the North Pole two years earlier as he claimed. Now the American had to beat his rival to the South Pole, but he lost nerve. He feared that his Trimotor was too heavy, unreliable, and thirsty for such a flight.

The winter months gave Byrd a brief respite, but by November 1929 Wilkins was on his way back to Antarctica, and Jack Northrop told the newspapers that “we will see a race between Wilkins and Byrd”. Byrd also knew that an Australian expedition led by Douglas Mawson was on its way to explore from the coastline around Enderby Land by air to claim it for Britain, and a Norwegian expedition was heading to roughly the same area, to use the same method. Among them was explorer Ingrid Christensen, who became the first woman to see Antarctica, fly over it, and maybe even the first woman to set foot on the Antarctic mainland.

So, at 3.30pm on Thanksgiving Day, 28 November 1929, Byrd took off for the South Pole and headed out into the polar wasteland.

The plane raced across the Ross Ice Shelf, and then laboured to climb up the Liv Glacier to the High Polar Plateau and the pole, but the glacier brought them face to face with a giant ice wall that appeared to be at least 1,500ft (500m) too high for the aircraft to fly over.

Desperately they cast their supplies out of the plane until, at the last minute, close to the ice wall, an updraft picked them up and threw them over the top.

Ten hours later, at 1am on 29 November 1929, Byrd reached the South Pole and dropped the US flag. Wilkins made several further flights, but none came close to rivalling Byrd’s achievement.

Then on Christmas Day, tragedy struck: another Norwegian aviator took off on a short flight, a storm blew up and was never seen again.

On overcast days when there is little contrast between the sky and the snow on the ground, flying can be extremely challenging (Credit: Vanderlei Almeida/AFP/Getty Images)

In January 1946, Admiral Richard Byrd ordered the brand-new aircraft carrier Philippine Sea to turn into the wind and six huge propeller-powered long-range Douglas Skytrain cargo planes were blasted into the sky by rocket packs for an eight-hour flight to the Bay of Whales, at Antarctica’s Ross Ice Shelf.

The 13 ships, 33 aircraft and 4,700 men of the US Navy’s Operation Highjump made it the largest expedition ever sent to Antarctica, the apex of the conquest by Antarctica by air, and the birth of a new era of science-led exploration. The goals of the massive expedition included naval preparedness for Arctic warfare; mapping the coastline of Antarctica; assertion of American territorial sovereignty over around 40% of the continent and scientific research. The expedition would climax with a rerun of Byrd’s 1929 flight to the South Pole. At the end of which, he dropped the flags of the United Nations over the Pole.

Byrd and his men made many new discoveries. Yet, without ground markers, many of the photographs his men took were useless, and by 1955 only about a third had been used for mapping.

For Dodds, exploration is “never neutral”, and that was certainly true of Wilkins, Byrd, and their kind. These men were motivated variously by personal challenge, discovery, wonder, science, and glory, but also by imperialism.

“In the 1920s, 30s and 40s there were mapping wars because the ownership of Antarctica was disputed,” says Dodds, “and what these countries were trying to do was to draw and publish as many maps of Antarctica as they could, in as much detail as they could, to establish their claim to it.”

The “mapping wars” led to the aviators on the 1939 German expedition dropping metal arrows emblazoned with the Nazi Swastika out of their flying boats to mark their land claim. Needless to say they weren’t particularly effective, but this didn’t stop Germany claiming a “vast Antarctic territory”. Following its defeat in the World War Two, Germany had to renounce any claims to Antarctica.

Aviation helped to confirm the ice-covered nature of Antarctica, which arguably contributed to a willingness to compromise in the Antarctic Treaty because there was little immediate prospect for economic gain – Adrian HowkinsWhat drove this land grab was whaling and the need to control the waters around Antarctica. Coal, oil and, later, uranium were next on the list, but no one really knew what was under the ice. It was suggested in 1940 that coal dust could be used to melt the ice, and after the war, nuclear bombs.

Yet Antarctica wasn’t carved up by the great powers. Instead, a new era of scientific exploration began to emerge. In 1955-56, Operation Deep Freeze saw the US Navy turn its attention to supporting American scientists on the scientific exploration of Antarctica. On 31 October 1956, the U.S. Navy did what many thought impossible, and landed a LC-47 Douglas Skytrain airplane at the South Pole. The following year brought an unprecedented programme of scientific collaboration under the International Geophysical Year (IGY) of 1957–58, which in Antarctica involved the scientists from around 70 nations.

This new focus on science also brought more women to the continent. In 1968, at the age of 72, Argentinian Irene Bernasconi became one of the first woman scientists to work on the continent – following in the footsteps of Jackie Ronne, who in 1947, became the first woman to explore Antarctica as a working member of an expedition, and who along with Jennie Darlington became the first women to overwinter in Antarctica. Ronne would return a total of 15 times to the Antarctica, including on a US Navy-sponsored flight to the South Pole in 1971.

By far the most important achievement to emerge from the endeavours of the IGY was the Treaty of Antarctica, which was signed in 1959 and committed 12 nations to a demilitarised, peaceful continent based on the principle of international scientific cooperation. That number has now swelled to 46 nations.

“Aviation also helped to confirm the ice-covered nature of Antarctica, which arguably contributed to a willingness to compromise in the Antarctic Treaty because there was little immediate prospect for economic gain,” says Howkins.

Science has become the “currency” of the continent, and building infrastructure, like runways, keeps it flowing by allowing aircraft to continue to arrive..

“Antarctica runs by air,” says Felicity Aston. “Shipping is important, but it is due to all those early aeronautical expeditions of the 1920s and 1930s, that we have all those air logistics that are so vital to the science programmes, as well as the tourism and the exploration in Antarctica.”

Richard Byrd’s flight over the South Pole and subsequent missions helped to fire the public imagination and support for expeditions to Antarctica (Credit: Bettmann/Getty Images)

“Aviators such as Richard Byrd were hugely influential in firing the geographical imaginations of the publics [around the world],” says Dodd.

The movie With Byrd At The South Pole won an Oscar for its cinematography. His book Alone is one of the classics of polar literature. The movie about Operation High Jump – The Secret World – won an Oscar for best documentary

Yet, tensions remain. The Antarctic Treaty has merely frozen territorial claims rather than resolving them, and many countries like Russia and China want their place on the ice. And the melting ice sheet is threatening to trigger new disputes over the territories by making it easier to mine the mineral wealth buried beneath.

“Surveying to reveal the location of valuable resources is banned by the treaty,” says Felicity Aston. “But it’s highly improbable that with all the geological surveys going on that scientist don’t already have a pretty good idea where the resources are.” And there is powerful lobby working to allow mining on the continent.

Also, the air forces of many nations still make their presence felt on the continent through operations to support scientific research.

But flying is still dangerous in Antarctica. In 2019, a Chilean Air Force C-130 Hercules crashed with the loss of 38 passengers and crew after the aircraft broke up in flight, or on hitting water. The cause of the crash is unknown.

That said, it can now take as little two weeks for a scientist to leave their home comforts and be deployed in the field, “massively extended the working seasons of the science teams”, says Rodney Arnold, the head of the air unit at the British Antarctic Service, and allowing organisations like his to attract a wider range of scientists to the continent.

Douglas Dakota-Skytrains still do much of the heavy lifting, and remanufactured as the Basler BT-67, demand for these tough American heavy lifters is increasing. Some, renamed as Snow Eagle 601, can even be found in the colours of China.

Now with the coming of the drones, and if built, the new Australian concrete runway could lead to all-year-round flights. It may mean much more of the frozen continent is explored from the air.

* Mark Piesing is the author of N-4 Down: The Search for the Arctic Airship Italia, the true story of the largest polar rescue mission in history.

August 30, 2021

International Competition is Heating Up in the Arctic. These Norwegian Islands Show How It Can Be Managed.

Ice melts near Nordenskjodbreen glacier on the Svalbard archipelago.Maja Hitij/Getty Images

Ice melts near Nordenskjodbreen glacier on the Svalbard archipelago.Maja Hitij/Getty ImagesAbout the author: Mark Piesing is the author of N-4 Down: The Hunt for the Arctic Airship Italia.

In the Arctic, the temperature is not the only thing that is heating up. Political tensions are rising, with squabbles over sea lanes, oil and gas resources, and ownership of millions of square miles of land.

Read my comment piece for Barron’s in full below, or the original by following this link.

In the Arctic, the temperature is not the only thing that is heating up. Political tensions are rising, with squabbles over sea lanes, oil and gas resources, and ownership of millions of square miles of land.

Great powers have clashed over the Arctic before, reaching a peaceful resolution after the end of World War I. This was the 1920 Svalbard Treaty: one of the few parts of the Versailles settlement that have survived the conflicts of the 20th century.

There is still something of the frontier about Svalbard. The Norwegian archipelago, 500 miles from the North Pole, is covered by snow and ice and dominated by gleaming white mountains. Dotting the mountainsides are long-abandoned mines and the remains of miners’ cabins. Near the airport is the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, guarantee of the world’s crop diversity.https://tpc.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-38/html/container.html

While researching my book N-4 Down: The Hunt for the Arctic Airship Italia, I had my picture taken, quickly, by the sign with a polar bear inside a big red triangle on the edge of Longyearbyen, the capital of the islands. Underneath read “Gjelder hele Svalbard,” meaning “applies to all of Svalbard.”

Svalbard is a place of hope for humanity. The mountainous islands were “officially” discovered in 1596 by Dutch explorer Willem Barents. They became legally terra nullius, or nobody’s land, visited by whalers from many countries who fought each other for control and traders and trappers from northern Russia called the Pomors whose visits may predate Barents.

In the years before World War I, European and American companies began mining on the islands, in part because of the coal reserves, but also because of their legal status, which meant there were no taxes or laws. Longyearbyen was founded by the American-owned Arctic Coal Company and named after John M. Longyear, one of its founders, who argued for the United States to take over Svalbard.

The “coal rush” then turned into a coal war over sovereignty, but this was resolved at the Versailles Peace Conference, thanks in part to a collapse in the price of coal and chaos in Germany and Russia.

The resulting Svalbard Treaty gave Norway sovereignty over the islands, but also gave other signatory states and their citizens (which now includes North Korea) the right to live there, carry out commercial activities, exploit resources, and own property. There are around 3,000 people living on Svalbard, including 500 who mine coal at Russian Barentsburg.

Taxes may be collected only for the benefit of Svalbard, so income tax is lower than on the mainland. Military activities are limited.

The Arctic is warming faster than any other region on Earth, and this has consequences.

While the sea ice is disappearing and polar bears face extinction, the hunt for oil and gas is moving north, and new routes for commercial shipping are opening.

Tragically, the Arctic is estimated to include 13% of the Earth’s oil reserves and a quarter of its untapped gas reserves. The untapped reserves in the Russian region alone have an estimated value of $35 trillion. Little wonder, President Putin is offering $300 billion of incentives for new projects.

Consequently, tensions between the Arctic powers are increasing and the historical, often conflicting, sovereignty claims are coming to the surface.

In the 1920s aviators such as Roald Amundsen and Umberto Nobile flew over the Arctic in fixed-wing airplanes and airships looking for undiscovered land and resources, ready to claim it for their country. Norwegian nationalists even dreamed of forging a “greater Norway,” with Svalbard the first step.

In the 21st century, Canada is claiming sovereignty over the Northwest Passage and up to the North Pole. Denmark lays claim to a large area up to and beyond the North Pole that is connected to the continental shelf of the Danish territory of Greenland—which may explain why President Trump was keen to buy it. Not to be outdone, Russia claims the Northern Sea Route and, indeed, much of the Arctic Ocean.

Some stunts used to assert these supposed rights have something of the theatricality of the 1920s about them, like the rustproof titanium flag that a Russian submarine planted on the seabed at the North Pole in 2007.

Others appear to be deadly serious. The Americans have accused the Russians of “militarizing” the Arctic. The Russian Northern Fleet regularly demonstrates its power in the Arctic Ocean, and has been building its military presence on nearby Franz Josef Land.

Then there is information warfare. The Norwegian celebrations of the centenary of the Svalbard Treaty in February 2020 led to three months of an “information offensive” in the Russian media against the Nordic country. Russian outlets pumped out aggressive messages claiming that these territories belong to Russia, and asserting that Norway must comply with their demands or face serious consequences.

It is not clear how serious this rivalry is. Oil and gas prices remain low, and it is hard to imagine NATO members Denmark and Canada going to war. The grievances that fuel the Russian demands could be resolved through diplomacy, but Oslo is intransigent and Moscow has proved adept at unconventional warfare.

In the end, the lesson of 1920 is that sovereignty claims could be resolved by a collapse in the price of oil and gas due to decarbonization, and a treaty that separates sovereignty and the right to exploit resources. Otherwise, conflict is likely.

I have just done my first podcast!

The Cosmic Controversy podcast covers past and present issues in aerospace and astronomy and is hosted by science journalist, Forbes contributor, and “Distant Wanderers: The Search for Planets Beyond the Solar System” author Bruce Dorminey.

The week before last I was invited on to talk about my new book N-4 DOWN: the hunt for the Arctic airship Italia.

Listen to below, or clicking on this link.

Read Bruce’s great view of N-4 DOWN for Forbes here…When Airships Raced To Conquer The Arctic

Watch my talk about N-4 DOWN for The Explorers Club in New York. I am on 10 mins in.

August 26, 2021

N-4 DOWN: I just gave a talk for The Explorer’s Club!

Not bad! I woke up the morning after the talk to see this on the club’s homepage.

Not bad! I woke up the morning after the talk to see this on the club’s homepage.It was great to give a talk for the world-famous The Explorer’s Club in New York City about my new book N-4 DOWN: the hunt for the Arctic airship Italia, even if the time difference meant that it started at midnight UK time. Even better, the feedback from the audience was very good.

What’s more, my talk was at the end of an amazing week for any new author. A week that had seen The Wall Street Journal give N-4 DOWN, my first book a very good and prominent review, The Wall Street Journal’s Book newsletter recommend it as a Nonfiction True Page Turner, and Forbes described it as “compelling” and “refreshingly well written.”

If you missed my talk then you can catch it below!

The excellent Michael Green introduces the talk and I am on 10 minutes later.

July 8, 2021

Breaking: N-4 DOWN included in Publishers Weekly pick of Adult Books Autumn 2021!

I have just had some great news!

My book N-4 DOWN: the hunt for the Arctic airship Italia has been included in Publishers Weekly pick of books to be published in Fall 2021.

Category: History.

Publishers Weekly just happens to be the bible of the US publishing industry.

It wasn’t in the top-ten for History, but it is on the “longlist of picks you’ll want to have on your radar”, and I will take that!

June 6, 2021

Updated: What people are saying about N-4 Down: the hunt for the Arctic airship Italia.

I woke up to discover that my first book had been reviewed in The Wall ST Journal!

I woke up to discover that my first book had been reviewed in The Wall ST Journal!I will update this page with reviews of N-4 DOWN: the hunt for the Arctic airship Italia.

“In compelling prose, Piesing draws us into the feverish efforts to conquer the Arctic by air.” –Bruce Dorminey, When Airships Raced To Conquer The Arctic, Forbes.

“N-4 Down works in large part because it is refreshingly well-written. So often these days, books tend to be published by historians and researchers who are experts in their fields but who can’t turn a phrase. So, it was a pleasure to be captivated by a working journalist like Piesing’s ability to put together a swath of prose that actually made me want to turn the page.”– Dorminey.

“Piesing’s narrative latches hold in part because although we live in an era in which there’s a lot of talk about pushing the limit of aerospace exploration, it’s been decades years since Amelia Earhart, Richard Byrd and Amundsen routinely risked their lives for the sake of aeronautical exploration.” — Dorminey.

“Piesing deserves credit for bringing this forgotten bit of aerospace history back to light.”– Dorminey.

The Wall Street Journal Books newsletter 20/8 recommended N-4 DOWN as 1 of 2 Nonfiction True Page Turners

The Wall Street Journal Books newsletter 20/8 recommended N-4 DOWN as 1 of 2 Nonfiction True Page Turners“One of the greatest polar rescue efforts ever mounted, a saga that journalist Mark Piesing retells in N-4 Down.”- Diana Preston, N-4 Down Review: Above The Ice, The Wall St Journal

“Mr. Piesing writes with obvious enthusiasm for his subject. His depictions of airship flight are gripping, whether he’s discussing the Norge’s 1926 journey over an icy wasteland traversed by Arctic foxes and polar bears or the doomed Italia’s final hours.” – – Preston

“This is a book with much to enjoy and a good illustration of what human curiosity, determination and courage—and sometimes a healthy dollop of vanity—can achieve.” — Preston

“Mark Piesing evocatively brings to life a lesser-known tale in the ill-fated history of polar exploration. Like the stories of Franklin and Shackleton, it combines triumph, disaster, heroism, hubris and mystery—but unlike them it features dashing aviators in airships and seaplanes. It is an epic tale that deserves to be far more widely known.” — Tom Standage, New York Times bestselling author of A History of The World in 6 Glasses

“A meticulously researched and utterly gripping account of adventure, airships and adversity, Mark Piesing’s N-4 Down is a brilliant book. Packed with a cast of vivid characters, magnificent flying machines, political machinations and tales of survival against all imaginable odds, it depicts one of the most extraordinary stories of not just aviation and exploration, but the twentieth century as a whole. You will never forget General Nobile, the airship and the endless ice they faced.” — Michael Bhaskar, author of Human Frontiers: The Future of Big Ideas in an Age of Small Thinking

“N-4 Down is a gripping, detailed tale of exploration, betrayal and rescue. Mark Piesing has crafted a fascinating recounting of a liminal time when flying and polar expeditions were equally risky, so of course people tried to combine them. Think The Terror, but with airships.” — Charles Arthur, author of Social Warming and Digital Wars, former technology editor at The Guardian

“The author has visited the places about which he writes, and his sketches of remote locales make for interesting reading. He also offers useful insights on the strange blend of competition and cooperation that characterized Arctic exploration. … Of interest to would-be Arctic explorers and armchair adventurers.” — Kirkus Reviews

Pre-ordering the book really helps the author. So if you want to pre-order then click on one of these links…

Amazon UK

amzn.to/2Zg5qMh

Amazon USA

https://amzn.to/3z9ggV0

Amazon Canada

https://amzn.to/3jJizal

Barnes and Nobile

bit.ly/3qjwvKC

Bookshop.org

lnkd.in/dEgsDqy

FNAC

bit.ly/3qxR9GI

Hugendubel

bit.ly/3jMCUvf

Waterstones

https://bit.ly/34UKAVy

What people are saying about N-4 Down: the hunt for the Arctic airship Italia.

Thanks Mara for this great review!

Thanks Mara for this great review!I will update this page with reviews of N-4 DOWN: the hunt for the Arctic airship Italia.

“A meticulously researched and utterly gripping account of adventure, airships and adversity, Mark Piesing’s N-4 Down is a brilliant book. Packed with a cast of vivid characters, magnificent flying machines, political machinations and tales of survival against all imaginable odds, it depicts one of the most extraordinary stories of not just aviation and exploration, but the twentieth century as a whole. You will never forget General Nobile, the airship and the endless ice they faced.” — Michael Bhaskar, author of Human Frontiers: The Future of Big Ideas in an Age of Small Thinking

“N-4 Down is a gripping, detailed tale of exploration, betrayal and rescue. Mark Piesing has crafted a fascinating recounting of a liminal time when flying and polar expeditions were equally risky, so of course people tried to combine them. Think The Terror, but with airships.” — Charles Arthur, author of Social Warming and Digital Wars, former technology editor at The Guardian

“Mark Piesing evocatively brings to life a lesser-known tale in the ill-fated history of polar exploration. Like the stories of Franklin and Shackleton, it combines triumph, disaster, heroism, hubris and mystery—but unlike them it features dashing aviators in airships and seaplanes. It is an epic tale that deserves to be far more widely known.” — Tom Standage, author of A History of The World in 6 Glasses

Pre-ordering the book really helps the author. So if you want to pre-order then click on one of these links…

Amazon UK

amzn.to/2Zg5qMh

Amazon USA

https://amzn.to/3z9ggV0

Amazon Canada

https://amzn.to/3jJizal

Barnes and Nobile

bit.ly/3qjwvKC

Bookshop.org

lnkd.in/dEgsDqy

FNAC

bit.ly/3qxR9GI

Hugendubel

bit.ly/3jMCUvf

Waterstones

https://bit.ly/34UKAVy

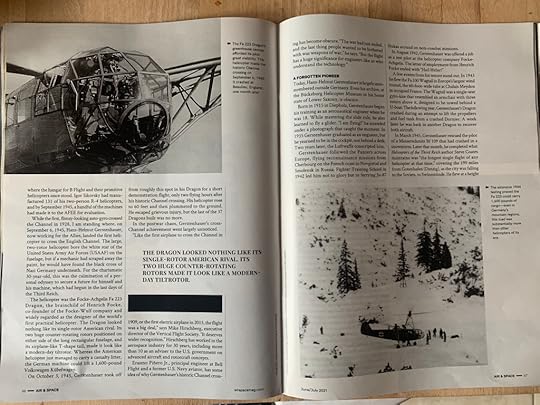

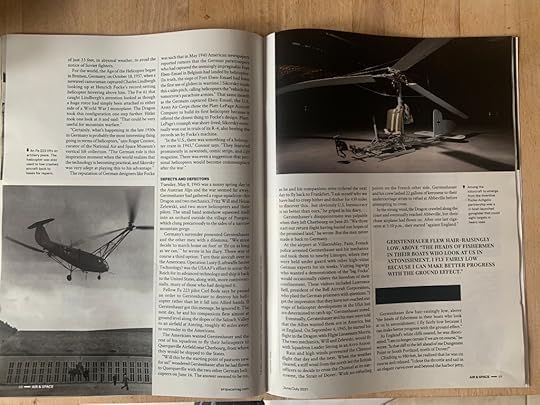

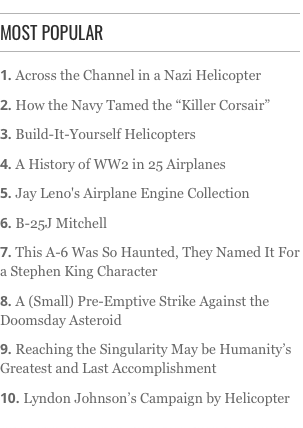

Across the Channel in a Nazi Helicopter

While the 1st, flimsy-looking auto-gyro crossed the English Channel in 1928, I am standing where, on September 6, 1945, Hans-Helmut Gerstenhauer, an engineer now working for the Allies, landed the first helo to cross the Channel…

See the rest of my first feature article – four stunning double pages! – for the Smithsonian’s Air and Space magazine by scrolling down, or clicking on this link.

Thanks to my editor Chris Kilmek, and the rest of the editorial team, for their time and support.

May 21, 2021

What is happening with my book? A lot!

I love this cover!

I love this cover!

“A meticulously researched and utterly gripping account of adventure, airships and adversity, Mark Piesing’s N-4 Down is a brilliant book. “

Michael Bhaskar, author of Human Frontiers: The Future of Big Ideas in an Age of Small Thinking

My book N-4 DOWN: The hunt for the Arctic airship Italia is due to be published on August 31, 2021 and this means that the production deadline is now very close.

SO I have been really busy working on

Reviewing the galley proofs

Asking other writers to read the book and give me a few lines for the cover of the book.

And then there was the exciting, worried, wait for the first feedback.

Thankfully, they were very good!

Answering questions from the proof reader.

Choosing the pics, their order, the captions and the licences.

Reviewing the layout of the photographs and their captions.

Pre-ordering the book really helps the author. So if you want to pre-order then click on one of these links…

Amazon everywhere

amzn.to/2Zg5qMh

Barnes and Nobile

bit.ly/3qjwvKC

Bookshop.org

lnkd.in/dEgsDqy

FNAC

bit.ly/3qxR9GI

Hugendubel

bit.ly/3jMCUvf