L. Jagi Lamplighter's Blog, page 28

October 24, 2014

Writing Chat with me on

I am doing another free online writing chat at Savvy Authors, next week:

Wednesday, October 29th, at 9:00pm EST.

Topic: Writing Dynamic Descriptions

Here is the info. You need to sign up if you want to participate, but it doesn't cost anything (Even though they ask you to 'check out.'):

You can register here: Savvy Author's Event

October 23, 2014

Mab’s Handy Guide To Surviving the Supernatural: Dragon World Tour

Hey Folks,

Mab Boreal here. You know me—the Northeast Wind who works for Prospero Inc. as a company gumshoe.

It has come to my attention that many of you are woefully uninformed about dragons. More innocent tourists get eaten every date. Yeah, they blame on natural disasters, terrorists and outbreaks of disease, but we all know its dragons.

Well, not all of it. There are a lot of other nasties out there. But dragons eat more and more people every year.

So, my assistant and I are going on a special world tour. We’ll be checking out the dragons in each part of the world and giving you a few pointers on how to avoid a fiery, roasted death.

Without further ado, let the Dragon World Tour begin!

Name: Classic Western Dragon

Description: Big, scaly fellow. Typically looks a bit like a giant iguana with wings. Can breath fire. Sometimes has horns or a bit of a beardlike thing going. Is usually lizard-color, greens and browns, but is occasionally red or black. Often has bigger scales on the stomach, some times of a contrasting color. Has four legs and two wings and a long tail, usually with a spiky ridge on the top.

Really likes gold. A lot. Like, even more than you do. Usually has a huge hoard of it that it sleeps on. Often gotten by eating Nibelung and keeping their stuff.

Dragon comes from the Latin word: draconem (nominative draco), which in turn comes from the Greek: δρ?κων (drák?n) which means truly gigantic water serpent, or something of that nature.

Dragon teeth, should you be so lucky as to see them outside of the dragon’s mouth…because otherwise they are probably the last thing you’ll see before you are fricasseed…can be tossed into the earth to produce crazy fighting men who will fight each other until you get a few guys left who might, if you’re luck, fight for you instead of attacking you.

Maybe.

Classical Western Dragons are not nice customers. They are in fact, cranky, nasty, malicious, angry buggers who are perpetually in a bad mood and can only be placated with maidens or a really large group of sheep.

Except for the Welsh dragons. In Wales, the red dragons are good guys.

October 22, 2014

Superversive Literary Blog — Deeper Magic From Before The Dawn Of Time

Welcome back to our weekly post on the Superversive Literary Movement.

This post is on one of my favorite things of all things: Christian Magic.

Travis Perry at Travis’s Big Ideas has an excellent article on ways that Christians handle magic to make it more or less in keeping with the Bible. You can see it here:

Seven Ways To Deal With The Problems Magic Poses Christian Fantasy Writers

http://travissbigidea.blogspot.com/2014/08/7-ways-to-deal-with-problem-magic-poses.html

This post is not on that.

For decades, there has been a large gap between traditional fantasy stories and Christian stories—fantastic or otherwise. This gap is growing smaller, especially with the existence of such things as Enclave Publishing, which specializes in Christian fantasy and science fiction. However, if the gap has been crossed successfully, more than possibly a few times, I have not yet heard about it.

What is this gap?

It is the gap between the wondrous and the pious.

The traditional fantasy stories include very little reference to Christianity. Many are overtly anti-Christian. The Christian stories, on the other hand, tend to be overtly pious, with no ambiguity or deviation from the particular strict doctrine.

I don’t know about you, but my life is not like that.

My life is more like being behind enemies lines. All around me is the secular world, filled with its terrors, its sorrows, its terrible doubts. I find myself challenged from all directions—both by the difficulties of life and by the skepticism of mankind. Those who are not Christian question my reliance on God, and many who are want to argue with me about the particulars of how to worship.

Yet, in the midst of all this comes glimpses of brilliant light, as if the Hand of God itself reached down from Heaven and touched some aspect of my life.

Miracles occur.

Many of them would not convince a skeptic. They are too subtle to point at: a sudden release from dark thoughts, an unexpected change in a seemingly hopeless situation. But some are more obvious: poison ivy on a baby instantly healed, a baby with a high fever instantly healed, back pain instantly relieved, Lime’s disease, which had progressed to such a degree as to cause semi-paralysis, instantly healed. The list could go on and on.

To continue, however, would be to miss the point, which is that it was not the physical changes that made the events so amazing, but the spiritual uplift that came with them. The moment when there was no hope—and suddenly, hope was present after all.

Unexpected touches of grace.

That is what I find missing from most overtly Christian stories, that moment when something totally unexpected but totally real happens. How could they be there, if the religion is so obvious that no one could miss it?

Where are the stories about people who discover the wonder and majesty of God, the way cleaning maids come upon unicorns or farm boys discover that they are Jedi?

Where are the stories that are as amazing as what happens to Gideon in the Bible? Or to Elisha? Or to Jacob?

(And if you have forgotten how utterly amazing and unexpected it is when three hundred men route an army, or when chariots of fire appear on the mountain, or when an angry, betrayed man who is coming to kill his brother suddenly embraces him instead, you might enjoy rereading a few of these stories.)

They that be with us are more than they that be with them. (2 Kings 6:16)

At this point, I must digress and discuss the purpose and meaning of magic in stories. In real life, I am not a fan of magic, if by magic, you mean the occult: casting spells, reading tarot, praying to gods, and other things that try to usurp the power of the Creator into our own hands (or the hands of some lesser power). I don’t personally find these things offensive. I have friends who enjoy them regularly. However, my personal experience suggests that those who engage in such pursuits may ultimately regret having done so.

But is magic in stories the same as magic in life?

I believe that it is not.

Or rather, I believe that magic in stories can have two different interpretations or purposes.

The first is the same as real life—the occult. People who worry that reading fantasy will lead to interest in the occult are worried about this interpretation. And they may have some grounds for concern. I fear good Professor Tolkien would be rolling in his grave if he knew how many modern Wicca had found their way to their current beliefs by first stepping upon the path trod by Bilbo. (Spinning fast enough to run a generator…but I digress. This is not an essay on Tolkien Power.) I personally have a family member who pulled out his tarot cards and crystal ball every time a new Harry Potter book came out. But, then, my family member is mentally ill and may not be a good indicator of the reading population in general.

The second is as analogy, when magic in a tale represents the sense of wonder that would come from greater things in real life. In this sense, the magic in a story represents the existence of wonder, of things greater than our eyes ordinarily show us, of hope.

Because, when praying, faith is required—and by faith here, I mean, specifically, a willingness for the prayer to actually be answered. One of the things that kills faith the quickest is doubt, lack of hope, a sense of certainty that the bad situation will never yield. This tends to interfere with the sense of acceptance of good often necessary for miracles.

So to the degree that magic in a story reminds us that there is more to life than what we see—that we should be open to the new and unexpected, to hope—I see it as a very positive thing.

Perhaps, there are those who read fantasies and turn to the occult, but then I also know people who, even as adults, credit their coming to Christianity to having read the Narnia books as a child.

Let me use an example: In the movie, Polar Express, the young man doubts the existence of Santa Claus. He wants to believe, but he doesn’t want to be fooled, bamboozled. There are two ways a Christian can take this.

1) This movie encourages belief in an idol, Santa Claus. It does not talk about God or Jesus, and thus takes away from the true meaning of Christmas. It is blasphemous.

2) The boy’s struggle concerning his faith in Santa Claus is an analogy for our struggle with our faith in God—where we want to believe, but we don’t want to discover t hat we’ve been fooled, bamboozled. This analogy reminds us of our own struggles and leads us to examine our faith more closely and thus is a signpost on the path to God.

This second option is how I, personally, view this movie, which is why I love it so very much. I always walk away feeling inspired to renew my efforts toward a more perfect faith.

And this is how I view magic in stories—not as a symbol of the occult, but as an analogy to help wake us out of the dreariness of our false concept of real life. It reminds us of that the real world is much vaster and more wondrous than we tend to give it credit for.

So, having come this far, what is it that I mean by Christian Magic?

I mean when something happens in a story that feels like magic-all marvelous and wondrous—but its source is Judeo-Christian, rather than occult or pagan.

In Narnia, we are told that the White Witch knows Deep Magic from the dawn of time. This allowed her to claim the right to slay Edmond the traitor. But Aslan knew a deeper magic still:

"It means that though the Witch knew the Deep Magic, there is a magic deeper still which she did not know. Her knowledge goes back only to the dawn of time. But if she could have looked a little further back, into the stillness and the darkness before Time dawned, she would have read there a different incantation. She would have known that when a willing victim who had committed no treachery was killed in a traitor's stead, the Table would crack and Death itself would start working backwards." (Aslan, The Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe.)

If you can read the last line and not have your heart lift, even slightly, this post—and the whole Superversive movement—is not for you.

And it may not be. No literature is for everyone.

But if you read this, and the notion that Death itself would start working backwards touches something deep inside you—like a finger from on-high brushing the harpstring of your soul—and your whole being thinks: Yes! Then, this whole effort is for you, just for you, and for those who—to paraphrase John Adams from 1776—see what you see.

End of Part One. (Next time, in two weeks, actual examples of Christian Magic in stories.)

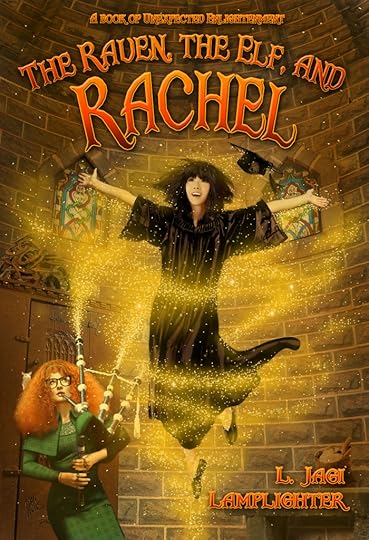

Today is the Day! Buy Now: The Raven, The Elf, and Rachel!

Today, we are doing a huge push for my latest novel

This is a great day to buy, as it will really help our numbers.

And whether you wish to buy or not,

Please share!

Finally, at last, the continuing adventures of Rachel Griffin!

Available in:

Thank you! Thank you!

October 20, 2014

Caption This!

October 15, 2014

Superversive — Guest Blog by Sarah A. Hoyt

Guest post by author extradinaire, Sarah A. Hoyt:

What did I want?

I wanted a Roc's egg. I wanted a harem loaded with lovely odalisques less than the dust beneath my chariot wheels, the rust that never stained my sword,. I wanted raw red gold in nuggets the size of your fist and feed that lousy claim jumper to the huskies! I wanted to get u feeling brisk and go out and break some lances, then pick a like wench for my droit du seigneur–I wanted to stand up to the Baron and dare him to touch my wench! I wanted to hear the purple water chuckling against the skin of the Nancy Lee in the cool of the morning watch and not another sound, nor any movement save the slow tilting of the wings of the albatross that had been pacing us the last thousand miles.

I wanted the hurtling moons of Barsoom. I wanted Storisende and Poictesme, and Holmes shaking me awake to tell me, "The game's afoot!" I wanted to float down the Mississippi on a raft and elude a mob in company with the Duke of Bilgewater and the Lost Dauphin. I wanted Prestor John, and Excalibur held by a moon-white arm out of a silent lake. I wanted to sail with Ulysses and with Tros of Samothrace and eat the lotus in a land that seemed always afternoon. I wanted the feeling of romance and the sense of wonder I had known as a kid. I wanted the world to be what they had promised me it was going to be–instead of the tawdry, lousy, fouled-up mess it is.”

Robert A. Heinlein, Glory Road

Lately there has been an argument raging, partly in #gamergate, partly in science fiction, and partly – as far as I can understand – in every single online group devoted to every single pastime that anyone ever dreamed up.

The argument, which seems almost ridiculous is simple: what is entertainment for?

Whether the entertainment is books, or computer games, or RPGs, there is a group of people saying that there is something wrong with escapism, something wrong with dreams.

They maintain that real adults; responsible and worthy people don’t want to escape the mundane realities of the real world. They want to be told about the downtrodden. They want to spend their entire time pondering what, in our society, is less than perfect. They want to think deep thoughts and be lectured about their inherent privilege and their shortcomings, what they have done and failed to do.

The purpose of fiction – insofar as fiction should be allowed at all – is to raise public consciousness; to spur us on to be better people, or at least to feel really bad when we aren’t.

Then there is the other side. The other side says while it’s permissible – and might in fact be impossible to avoid – to have the author’s point of view and his/her take on the world in a story, the main purpose of the story, the reason we read/play games is to escape, to dream, to be someone else doing something else.

I am solidly on the side of escapists, and I don’t think that wishing to enjoy a good tale makes you less mature.

Perhaps this opinion is influenced by the fact that I first started reading (everything I could get my hands on) because I was so sickly as a child. But the truth is that happy or sad, contented or not, I view reading as a chance to experience being someone else for a while.

There are lots of advantages to this, including that it promotes empathy and gives you knowledge of many times and places.

But it all starts with the dream; with wanting to be someone else, doing something interesting. If the dream doesn’t hook us, we don’t follow along and we don’t learn anything.

It seems to me that the other side’s opinion is driven by the fact that they have experienced too few challenges/real adversity. They seem to be, by and large, people who have had an easy time in life, and who therefore feel they have to justify their existence by thinking big thoughts and trying to correct big wrongs. But perhaps I am unfair to them.

Their side of the debate has always existed. In every human civilization there have always been those who think that any form of frivolity and amusement should be forbidden and that all of humanity’s powers should be devoted to making the world a better place.

It is just that throughout most of Western history the people preaching the more serious point of view, and how entertainment should follow a moral view were preaching Jewish/Christian morals and personal improvement.

I’m not going to pretend that I was enthralled with fiction that tried to serve that sort of moral purpose. I read the Countess of Segur’s more “moral” books – not the fairytales, but the stories of good little girls and bad little girls and perfect young men who get rewarded by becoming Swiss guardsmen and dying defending Rome – and I curled my lip and rolled my eyes with the best of them.

However, even when blatantly preachy, those books tried to build up civilization, for which one might perhaps forgive them their preachy tone.

The current wave of preachy fiction is the bastard child of Marxism by critical theory. It is just as preachy as the old stories, but he preaching it does seeks to tell us about vast classes of downtrodden (not as individuals, but as classes) and make us feel better for our privilege which apparently is something we have if we’ve ever worked or achieved anything.

It’s composed almost exclusively of stories in which no one is ever good or does anything good, and if a character who is well intentioned slips through, he must be beaten into a pulp and all his beliefs disproven.

I’m a depressive. I can be in that frame of mind, and often am. But I don’t mistake it for high art. Or for that matter for something I should inflict on others.

In reaction to this, in longing for the books of my childhood (even the one with the dying Swiss guard was more fun. At least it took place in Victorian France) I came up with the concept of Human Wave. (http://accordingtohoyt.com/2012/03/21/what-is-human-wave-science-fiction-3/)

Yes, it was partly done tongue-in-cheek to bounce off “New Wave” and partly symbolically to indicate a wave of human interest submerging the pointless stories.

I’ve been asked time and time again if Human Wave is superversive or Superversive is human wave.

I think that the two need not be contained one in the other. But in the sad state of affairs we’ve come to, in which most books feel at least the need to nod to Marxist tropes: to blame males; to make all women sound oppressed; to speak of the “problems in society” or to make humanity “a plague upon the Earth” for shock, for surprise, for the ability to transport you to a different time and place, Human wave is shocking enough to cause a frisson of wonder.

Human Wave is superversive.

If it succeeds, it might just be “normal.”

For more by Sarah, visit her blog, According to Hoyt

October 8, 2014

Holy Godzilla of the Apocalypse: or How to Identify a Superversive Story

So, you want to be Superversive? Eager to join the new movement but not sure how to tell if you have? This post will, God willing, help sort out a bit of the confusion.

So, without further ado: The Benchmarks of the Superversive:

First and foremost, a Superversive story has to have good storytelling.

By which I do not mean that it has to be well-written. Obviously, it would be great if every story was well-written. It is impossible, however, to define a genre or literary movement as “well-written”, as that would instantly remove the possibility of a beginner striving to join.

What I mean by good storytelling is that the story follows the principles of a good story. That, by the end, the good prosper, the bad stumble, that there is action, motion to the plot, and a reasonable about of sense to the overall structure.

Second, the characters must be heroic.

By this, I do not mean that they cannot have weaknesses. Technically, a character without weaknesses could not be heroic, because nothing would require effort upon his part.

Nor do I mean that a character must avoid despair. A hero is not defined by his inability to wander into the Valley of Despair, but by what he does when he finds himself knee deep in its quagmire. Does he throw in the towel and moan about the unfairness of life? Or does he pull his feet out of the mud with both hands and soldier onward?

Nor do I mean that every character has to be heroic, obviously some might not be. But in general, there should be characters with a heroic, positive attitude toward life.

However, many, many stories have good storytelling and heroic characters. Most decent fantasies are like that.

Are all decent fantasies Superversive?

No.

Because one element of Superversive literature is still missing.

Wonder.

Third, Superversive literature must have an element of wonder

But not ordinary wonder. (Take a moment to parse that out. Go ahead. I’ll still be here. )

Specifically, the kind of wonder that comes from suddenly realizing that there is something greater than yourself in the universe, that the world is a grander place than you had previously envisioned. The kind of wonder that comes from a sudden hint of a Higher Power, a more solid truth.

There might be another word for that kind of wonder: awe.

Specifically, the awe that comes when you are pulled out of your ordinary life by being made aware of the structure of the moral order of the universe.

That kind of awe.

To be Superversive, a story needs that moment when you are going along at a good clip and you suddenly draw back, because you have been lifted outside of yourself by the realization that there is something Bigger.

(And I don’t mean bigger like Godzilla. Just the God part. No zilla. Unless this Godzilla works for God. Godzilla, Holy Monster of the Apocalypse, or something.)

On this blog, I will often talk about Christian Superversive stories. Stories that have that moment, when the greater truths of the Creator of the Universe are suddenly glimpsed by the reader and/or the characters in the story.

If the Superversive Movement is about storming the moral high ground—bringing a moral order into our stories, adding the power of a greater truth. Then, the most effective stories are likely to be the ones that reflect the author’s highest sense of truth. For me, that means the truths of Christianity, as I understand it.

However, I want to make it clear, right from the beginning, that Superversive literature does not have to be Christian. You can write Jewish Superversive or Buddhist Superversive. It does, however, require a moral order and a glimpse of the awareness of this order in the story.

My favorite movie of all time is Winter’s Tale, the movie made from Mark Halprin’s novel. Winter’s Tale is Jewish Superversive.

What makes it so good is these moments I refer to above, moments that take you out of yourself and make you realize that something Bigger is going on. (Again, not Godzilla…except for Holy Godzilla, who most likely lives in a Pokaball on Batman's belt…so Robin can shout out: Holy Godzilla, Batman! And Batman can shout, "Holy Godzilla, I choose you!" and Holy Godzilla can appear and stomp on the Joker (and probably half of New York, too, but…ah well.)

My favorite TV show, Chinese Paladin Three, is Taoist Superversive. You are going along, minding your own business, enjoying this pure fantasy romp, and suddenly, toward the last third, there is this section where the villain tries to convince the Taoist priest of the futility of the human condition.

The story line suddenly becomes so deep and so touching, so insightful and so unexpected. The depth of the moral questions being presented to the priest character and the horror of what he suffers adds a whole vertical dimension to what had previously been a lighthearted adventure.

It brings a sense of awe.

Two questions come to mind:

1) Can you write Wicca or Pagan Superversive?

Possibly, but it would be difficult. Why? Because fantasy…gods, myths, etc…is the matter of Pagans. If the story starts out about such things, adding more of the same is not superversive.

However, if the story were about, say wizards or nymphs and fauns, or any other worldly matter, and the gods made brief unexpected appearances in which they put across moral ideas that lifted the story to a higher level, that might possibly be superversive. (Gene Wolfe’s Solder In The Mist comes to mind.)

2) Can Christian Fiction (or Jewish Fiction, or Taoist Fiction) be superversive?

Probably not. It certainly could be inspirational, if done well. But if something starts out already being about these matters, then it is not superversive to introduce them. It is just part of the tale. Such a story could be written in a way that would make it enjoyable to those who love superversive stories, but it would not be superversive in and of itself.

An Example:

I don’t want to give too much away about Winter’s Tale, part of the wonder of the story is that everything is so unexpected. But I think I can describe this scene without ruining too much of the joy.

Crime boss Pearly Soames approaches another man in 1915 New York, reminding the second man that he owes Pearly a favor. He asks for help in his plan to kill Beverly Penn. The second man wants nothing to do with it, but Pearly calls the debt and insists.

Then, suddenly, in the midst of this intrigue scene, Pearly says:

I've been wondering.

With all these trying to go up…and you come down.

Was it worth it, becoming human? Or was it an impulse buy?

You must miss the wings, right?

Oh, come on. You must.

And in that instant, you suddenly realize that something very different is going on that you first thought, and it opens a glimpse into some greater working of the universe, a glimpse that makes you pause and think…about heaven and fallen angels and what it means to be human and whether it is a good thing or no.

And that, my friends, is Superversive.

October 6, 2014

Caption This

Capture This Winner

We received some great captions, but the most popular was was, hands down:

Aren't you a little short for a Storm Trooper?

However, a special mention to:

These are not the Little Ponies you are looking for.

October 1, 2014

The Art of Courage — Superversive Guest Post by Tom Simon

The Superversive Literary Movement

Good storytelling. Great ideas.

Greetings, and welcome to the first post of the new Superversive Literary Movement blog, which will appear here on Wednesdays (or occasionally Thursday, if life interferes.)

Our very first post is an introduction to the concept of Superversiveness by Mr. Superversive himself, Tom Simon!

The Art of Courage

by Tom Simon

Behold the Underminer! I am always beneath you, but nothing is beneath me!

—The Incredibles

For about a hundred years now, ever since the First World War broke the confidence of Western civilization, it has been fashionable to praise subversion. Art, music, and literature, as many of the critics tell us, are not supposed to go chasing after obsolete values like truth or beauty; they are supposed to shock, to wound, to épater les bourgeois – to subvert the values of society. Here is a fairly typical example, from the literary critic, John Grant:

It must meddle with our thinking, it must delight in being controversial, it must hope to be condemned by authority (whatever authority one chooses to identify), it must be at the cutting edge of the imagination, it must flirt with madness, it must surprise.

Grant is prescribing goals for fantasy, but the same demand has been heard in every genre and every art form, much to the harm of the arts. Most people don’t share Grant’s ideological preoccupations; they see the arts not as vehicles of propaganda, but as entertainment. Trying to get yourself condemned by authority may be good sophomoric fun while you are doing it, but it makes a dull spectator sport. Considered as entertainment, it has no virtue except novelty; and it has not been novel since about the 1920s. This is one reason why the ‘serious’ arts see their audiences shrinking year after year, until they are only maintained in precarious existence by public subsidy.

Part of the trouble comes from that apparently blank cheque, ‘whatever authority one chooses to identify’. In practice, this always means the same authority: the ghost of Mrs. Grundy, the narrow-minded, puritanical, bourgeois authority that lost most of its power in 1914, and does not exist at all anymore. If you rebel against a different authority – the Chinese Communist Party, or the rulers of militant Islam – you will not find the critics so approving. They will call you reactionary or even neocon, and the hand of Buzzfeed will be raised against you.

For the world of art and literature is largely dominated by the Left, and the Left is dominated by people whose world-view is inherited from their great-grandfathers. In this view, we need labour unions to defend us against the peril of child labour, Big Government to defend us against Standard Oil. America is one false move away from theocracy and Jim Crow; Europe is one false move away from another World War. Nothing can save us except a wonderful new panacea called Socialism, which has never been tried before, and with which nothing can possibly go wrong. These, in the main, are the ideas of the Left even today; and the people who believe these things have the nerve to call themselves Progressives. They call for progress; but they are still trying to progress from 1914 into 1915. They call for subversion; but the thing they are trying to subvert no longer exists.

To subvert a thing literally means ‘to turn from below’: to undermine. In olden days, men built their forts and castles on high ground, because high ground is easier to defend. A hilltop fortress can be made almost impregnable. But only almost: for a fortress can be undermined. The attacking army digs tunnels underneath the fortifications, scooping out the earth and rock until the walls cave in from their own unsupported weight. This is the original kind of subversion.

Nobody uses the word subversion in that literal sense anymore, but it is helpful to keep it in mind, because it applies metaphorically to every other kind of subversion. Our brave Progressive rebels have been subverting the walls of nineteenth-century capitalism and imperialism for a hundred years, and the walls fell down long ago. All that remains now is a hole in the ground, under which armies of activists like crazed moles are busily undermining each other’s mines. One mole calls another mole’s mine sexist, and digs a tunnel to make it collapse; the second mole calls the first mole racist, and digs a tunnel under that. They have lost the power to create; all they have left is the mere reflex of criticism.

At this point, subversives can do nothing but dig the hole deeper, or at best, rearrange some of the rubble on the surface. Further subversion achieves nothing; it creates nothing; but they go on doing it from sheer force of habit – the habit of feeding the ego. If they fought effectively, they might win, and then they would not feel needed anymore. As long as they fight by useless methods, the war can continue, and they can take pride in being on the right side.

On the face of it, this is insane; but it is exactly the kind of insanity that you will always find among sane people. It is the insanity of the committee, where people who disagree about their destination have to agree which road to take. Those who want to go north reject the road that goes south, and those who want to go south reject the road that goes east; in the end they compromise and take a road that goes round in circles. Ritual subversion satisfies the craving for activity without ever risking achievement.

G. K. Chesterton described the process in Heretics:

Suppose that a great commotion arises in the street about something, let us say a lamp-post, which many influential persons desire to pull down…. But as things go on they do not work out so easily. Some people have pulled the lamp-post down because they wanted the electric light; some because they wanted old iron; some because they wanted darkness, because their deeds were evil. Some thought it not enough of a lamp-post, some too much; some acted because they wanted to smash municipal machinery; some because they wanted to smash something. And there is war in the night, no man knowing whom he strikes.

The subversives have pulled down their lamp-post, and they must go on pulling it down for ever, because they cannot agree on what to do next.

What, then, can we do, those of us who are not Progressives? We cannot fight subversion by its own methods; that only makes the hole deeper. But if subversion means ‘turning from below’, there can be such a thing as turning from above. We have nothing to gain by digging a bigger hole, but we can build right over it. It seems natural enough to me to invent a new word for this by changing part of the old one; so I call it superversion.

The job of the superversive is at once difficult and rewarding. We shall need to build on the high ground, as people used to do: not only for defence, but because the high ground is more solid. Before the subversives dug their mines under the churches, there was a parable that used to be widely known. The gist of it was that a house built on rock will stand firm, but a house built on sand will soon fall down. High ground is usually rocky ground, and from that perspective, ideal for us to build on.

For those of us who write stories, this chiefly means moral high ground. I am not speaking of sexual morality; that, nowadays, is a subject so difficult to approach, so fraught with ego and emotion, that we are liable to lose most of our readers if we begin there. Fortunately, there are other areas of morality where most people still have an instinctive preference for the good. Progressivism tells us that we are all pawns pushed about by socioeconomic forces (which only the great god Government can hope to alter). Our instincts and experience are all on the opposite side. We know, and feel that we know, that individuals can actually do things, and sometimes great and heroic things. And we know that the best things are often done against the odds; the socioeconomic forces do not inevitably win. Progressivism sneers at the idea of good and evil; but we persist in admiring qualities like honesty, unselfishness, and fair dealing, and most of us feel shame when we do the opposite things. Most people like the kind of story that can be called heroic, where the main character wants something and accomplishes it in spite of opposition. Very few people like stories where all the characters’ actions are doomed to futility, no matter how much they were taught to admire such stories at school.

It has been truly said that courage is not a virtue, but the form that every virtue takes at the testing point. In this sense, most good stories are about courage – the courage to make a sustained effort. It takes physical effort to climb a mountain or build a castle; it takes an effort of will to lift yourself above your worse impulses and climb up to the moral high ground. That is one reason why the metaphor refers to high ground. Temptation is as universal as gravity, and we spend most of our time and effort resisting them both. It is true that courage is not an unmixed blessing. It can take as much courage to commit a murder as to save a life. But it is fair to say that no good thing was ever accomplished without courage; that our whole civilization is built on the courage of men and women who would not surrender to their circumstances, but strove for something better.

I believe it follows, then, that courage is the essential quality of a superversive story: not the dumb, dull fortitude that passively endures in the face of suffering, but the courage that allows the character to take action – to risk becoming a hero. In a double sense, fiction is the art of courage. It is the art that teaches courage by example; it is also the art that is about courage. If the characters have no problem, there is no story; but if they do not have the courage to try and solve the problem, the story has no point, and the audience will not be entertained. There are plenty of non-stories and pointless stories already; plenty of literature, full of pretty language and therefore praised by the critics, in which nobody does anything, or even tries. I say we have had enough of those stories. Let us be superversive; let us build on mountains instead of making molehills. Let us make up stories about people with courage, and have the courage to tell them, as much as the critics and the Progressives wish us to be silent.

Tom Simon is an author and essayist. He has written many really fine and inspiring essays on a host of topics, including some excellent essays on the works of J. R. R. Tolkien. To find out more about his work:

His blog:

http://bondwine.com

His author page:

http://www.amazon.com/Tom-Simon/e/B00AR3EN7G

His novel, Lord Talon's Revenge

Writing Down the Dragon ( and other Essays on the Tolkien Method and the Craft of Fantasy.)