Dimitra Fimi's Blog, page 3

November 2, 2019

TLS review of Ebony Elizabeth Thomas’s book The Dark Fantastic

Race in fantasy is a topic quite close to my heart: I wrote about Tolkien’s complex engagement with race and racial anthropology in my 2008 monograph Tolkien, Race, and Cultural History, summarizing some of my main findings in a later paper, now available here, and a recent article in The Conversation (which was reprinted multiple times). In 2015, Helen Young’s Race and Popular Fantasy Literature: Habits of Whiteness offered a winder discussion on race in fantasy, including in Tolkien’s precursors and followers.

Race in fantasy is a topic quite close to my heart: I wrote about Tolkien’s complex engagement with race and racial anthropology in my 2008 monograph Tolkien, Race, and Cultural History, summarizing some of my main findings in a later paper, now available here, and a recent article in The Conversation (which was reprinted multiple times). In 2015, Helen Young’s Race and Popular Fantasy Literature: Habits of Whiteness offered a winder discussion on race in fantasy, including in Tolkien’s precursors and followers.

Ebony Elizabeth Thomas’s book The Dark Fantastic: Race and the Imagination from Harry Potter to the Hunger Games is an important new intervention on Young Adult fantasy and race, examining some of the most popular YA fantasy text of the last two decades, including The Hunger Games (the novels, as well as the films). You can read my review of this book for the Times Literary Supplement (TLS) via this link: https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/private/dark-others/. I will post a longer review on this blog soon, so watch this space!

October 28, 2019

Samhain or Halloween? The “ancient Celtic year” in Contemporary Children’s Fantasy

* This essay was originally published in Gramarye , the journal of the Chichester Centre for Fairy Tales, Fantasy and Speculative Fiction, in Issue 11 (Summer 2017), pp. 51-63.

In the medieval Irish tale of Tochmarc Emire (“The Wooing of Emer”), Emer challenges Cúchulainn to remain “sleepless from Samain, when the summer goes to its rest, until Imbolc, when the ewes are milked at spring’s beginning; from Imbolc to Beltine at the summer’s beginning and from Beltine to Brón Trogain, earth’s sorrowing autumn” (Kinsella, 1969, p. 27). This much-quoted extract neatly outlines what have come to be known as the four “quarter-days” not only of the Irish medieval calendar, but – by extension – of the ancient “Celtic” year more generally: Samhain (31 October/1 November), Imbolc (1 February), Beltaine (1 May), and Lughnasadh (1 August). Each of these four festivals (or feast days) makes an appearance in a number of other Irish sources (though Samhain and Beltaine figure much more prominently), often becoming the setting for the main narrative action.

Among these four quarter-days, Samhain holds particular sway in the popular imagination, as it is often claimed to be the pagan “origin” of modern Halloween, the latter celebration supposedly still retaining pre-Christian elements of its “Celtic” predecessor. The argument for Samhain as an important “pagan” festival usually rests on its association with supernatural occurrences in the Irish medieval tales, on the claim that it was the “Celtic” festival of the dead (something that could point to religious observances), and on the widespread idea that is was the “Celtic New Year”, the beginning of the year, in contrast to the reckoning of years in the Roman calendar, starting on 1 January (see Roud, 2008, pp. 439-40; Davis, 2009, 29). However, each of these threads of the “pagan” argument can be (and have been) vigorously challenged.

The prominence of supernatural figures making their appearance on Samhain in the Irish medieval tales may not be linked with the remnants of a “pagan” religious celebration at all. There is no doubt that Samhain was a time of agricultural significance, the end of the summer and the beginning of winter, when livestock would return from pasture and perishable food would be consumed in a community setting (such as a feast) ahead of a time of more scarcity of resources. The Irish material does refer to feasts of kings and warriors on this day, but – as Ronald Hutton has noted – having important legendary characters gathered together for a feast “with time on their hands” is, naturally, an ideal time to begin a tale, “in the same way [that] many of the Arthurian stories were to commence with a courtly assembly for Christmastide or Pentecost” (1996, p. 362). In this scenario, it is not the feast itself that invites the supernatural, but the fact that it provides the opportunity for a gathering of characters who will experience adventures involving the supernatural. This is not to belittle the anthropological/folkloric idea of liminality (Van Gennep, 1960; Turner, 1967): Samhain would also be a fertile setting for the supernatural by virtue of being a time of transition between one season to the other. But there is nothing particularly “pagan” or exclusively “Celtic” about this – rites of passage and liminal times are much wider motifs, common in a number of cultures.

Coming to Samhain as a festival of the dead, this contention has been based on “working backwards” on the assumption that the Christian feasts of All Saints (1 November) and All Souls (2 November) usurped a pre-existing pagan festival. Sir James Frazer’s very popular work The Golden Bough (1906-15) supported this idea, which was then further reinforced by the sensation of Margaret Murray’s theory for a (supposedly) female-centric, nature-focused “Old Religion”, eventually supplanted by Christianity (see Davies, 2009, pp. 30-1; Hutton, 1996, 363-4). But this hypothesis collapses when one delves into ecclesiastical history. The feast of All Saints did not have a consistent date until the 9th century, when it was consolidated as the 1 November, followed by the feast of All Souls (commemorating all the faithful departed) which also became very popular. The date was not established by the church in Ireland, or any other “Celtic” region, but in the Germanic dioceses of Northern Europe (Davis, 2009, p. 31-2; Hutton, 1996, p. 364). There simply is no evidence for the Irish Samhain cunningly being “taken over” by Christianity.

The third line of argument is equally shaky. It was Sir John Rhys who first suggested that Samhain was the “Celtic New Year” in his 1901 work Celtic Folklore, based on very flimsy (and also contemporary, i.e. late-19th-/early-20th-century ) folklore evidence from the Isle of Man, and having previously cited unreliable or “corrected” Irish texts (see Davis, 2009, pp. 29-30; Hutton, 1996, pp. 363). The Tochmarc Emire order of mentioning the festivals, beginning with Samhain, may have also played a role in this identification. But there is no evidence whatsoever that the New Year started on 1 November in “pagan” Ireland or any other “Celtic” region. The only pre-Christian “Celtic” calendar in existence, the Coligny Calendar from 2nd-century Gaul, seems to begin the year in the summer, although the calendar was found in fragments and has been reconstructed in different ways, none of them conclusive (see Minard, 2006).

The elephant in the room in all of this discussion so far, of course, is the term “Celtic” itself, and the rather facile equation of “Irish” with “Celtic” in earlier scholarship (and, currently, in popular culture). I have recently surveyed the conventional narrative of the “Celts”, which seeks to create a linear history linking Iron Age cultures in the Continent and the British Isles, to medieval Ireland and Wales, all the way to modern “Celtic” identities in speakers of Celtic languages (including Scots Gaelic and Breton) or their Diasporas (see Fimi, 2017, pp. 7-9). Against this narrative, modern scholarship has taken a “revisionist” turn, pointing out a number of holes, assumptions, and assertions. First, the term “Celts” was attributed to a variety of peoples by classical commentators (and never by these peoples themselves). Second, the archaeological evidence doesn’t support the idea of mass migration of Continental “Celts” to Britain and Ireland. Third, the medieval Irish and Welsh did not see each other as having common ancestry or a shared cultural and linguistic heritage. Fourth, the idea of the “Celts” and “Celtic literature” as popularly understood today was really a product of the early modern and Romantic periods, ideologically linked with the “rediscovery” (or more often re-construction, and even forgery) of national “epics” or mythological texts, often to support (or react against) political agendas. Recent scholarship has even questioned the validity of the terms “Celt” and “Celtic” themselves (for an overview see Fimi, 2017, pp. 9-12).

The fact that the four “quarter days” found in Irish medieval literature have become known as the “ancient Celtic year” is a prime example of the problematic practice of assuming that all “Celtic” regions (if we can still call them that) had a homogenous culture in all of their constituent areas and at all times. As discussed above, Samhain is, indeed, an important date in the Irish medieval material, but the Welsh festival taking place on the same date, Nos Calan Gaeaf (Winter’s Eve), just doesn’t share this significance. On the contrary, the Welsh medieval tales set magical adventures and supernatural intrusions on a different date: on 1 May, or the previous day, May Eve (Calan Mai), corresponding to Beltaine in Ireland. Davis has drawn attention to the “problematic dependence on exclusively Irish material for the entire record of Samhain customs” and has noted that customs associated with Samhain are not attested “in any early Welsh or Scottish material, except in areas of heavy Irish migration” (Davis, 2009, p. 30). The fact that the Irish material is often richer, earlier, and more detailed, together with a facile pan-Celticism in earlier scholarship (and in modern popular understandings), has often made the equation Irish=(pan-)Celtic almost a default.

And this is where authors of Celtic-inspired children’s fantasy come in. In my recent monograph (Fimi, 2017), I examined a selection of contemporary children’s fantasy texts, ranging from the 1960s to the 2010s, analysing their creative adaptation of medieval Irish and Welsh narratives. Ultimately, I showed that each of these works of imaginative fiction constructed its own perception of “Celticity”, defined as “the quality of being Celtic” (Löffler, 2006, p. 387), and added another approach to the notion of “Celticism”, the study of the “reputation of [the Celts] and of the meanings and connotations ascribed to the term “Celtic” (Leerssen, 1996, p. 3). The imaginative ways in which these fantasy novels use the “ancient Celtic year” and the four “Celtic” quarter-days offer evidence of one more instance of their engagement with the “Celtic” past and illuminate their construction of “Celticity”. In the remainder of this essay, I will discuss examples of the “ancient Celtic year” and its appropriation in four fantasies: Mary Tannen’s Finn novels (The Wizard Children of Finn, 1981, and The Lost Legend of Finn, 1982); Jenny Nimmo’s The Magician Trilogy (The Snow Spider, 1986, Emlyn’s Moon, 1987, and The Chestnut Soldier, 1989); Susan Cooper’s The Dark is Rising Sequence (Over Sea, Under Stone, 1965, The Dark is Rising, 1973, Greenwitch, 1974, The Grey King, 1975 and Silver on the Tree, 1977); and Henry Neff’s The Tapestry series (The Hound of Rowan, 2007, The Second Siege, 2008, The Fiend and the Forge, 2010, The Maelstrom, 2012 and The Red Winter, 2014).

The most straightforward case is Mary Tannen’s Finn novels. This is a series of two books, in which two young American children, Fiona and her brother Bran, time-travel back to mythical Ireland at the time of legendary hero Finn mac Cumhall. Tannen is the only one of my chosen authors to mention all four “Celtic” quarter-days. They are designated as “magic nights” in both novels: they invite supernatural presences, facilitate the performance of magic, and allow a medieval Irish manuscript to become a portal that transports the children to ancient Ireland. Time-travel itself, therefore, is predicated upon the magical qualities of the quarter-days. In the first novel, Fiona and Bran time-travel to Ireland on Lugnasad on 1 August, and return on Samhain. The children also find out that Finn himself and his two female guardians, Bovmall (the Druid) and Lia (the warrior), have travelled forward in time to 20th-century USA on Beltaine, in late spring. In the sequel novel, Fiona and Bran access the past on Halloween/Samhain and return on Imbolc (1 February).

The most straightforward case is Mary Tannen’s Finn novels. This is a series of two books, in which two young American children, Fiona and her brother Bran, time-travel back to mythical Ireland at the time of legendary hero Finn mac Cumhall. Tannen is the only one of my chosen authors to mention all four “Celtic” quarter-days. They are designated as “magic nights” in both novels: they invite supernatural presences, facilitate the performance of magic, and allow a medieval Irish manuscript to become a portal that transports the children to ancient Ireland. Time-travel itself, therefore, is predicated upon the magical qualities of the quarter-days. In the first novel, Fiona and Bran time-travel to Ireland on Lugnasad on 1 August, and return on Samhain. The children also find out that Finn himself and his two female guardians, Bovmall (the Druid) and Lia (the warrior), have travelled forward in time to 20th-century USA on Beltaine, in late spring. In the sequel novel, Fiona and Bran access the past on Halloween/Samhain and return on Imbolc (1 February).

What is more, Finn uses the quarter-days in a conventional way, as often seen in medieval Irish literature, to mark the passage of time. When asked about his age he notes: “Tomorrow I will have passed through Lugnasad seventeen times” (Tannen, 1981, p. 48). At the same time, though, Finn’s reliance on the quarter-days rather than a Roman-style calendar and reckoning of the years, singles him out as pre-modern:

“Hey, Deimne,” Fiona said, acting on a hunch, “what year are we in?”

Deimne gave her a blank look.

“You know,” Fiona prodded, “like back home it was 1981. What year is it here? ”

“You’re a queer one,” said Deimne, “giving numbers to years. It’s just after Lugnasad. What more do you need to know?” (Tannen, 1981, p. 77)

Clearly, Finn, and by extension the “ancient Celts” (as the book calls the ancient Irish), has a concept of time as cyclical, as part of an ever-repeated pattern, rather than our “modern” idea of linear time. This plays into the hands of a common stereotype of the “Celts” as both rather primitive and romanticized (more intuitive/artistic than rational, in touch with nature and its cycles).

Tannen doesn’t give much information about Imbolc and Lugnasad (apart from their dates in winter and summer, and their status as “magical nights), but Beltaine is described a little more. Uncle Rupert calls it “the most magic night of all on the Celtic calendar” and Finn gives the children a full account on rituals and customs practiced on that day:

“Beltaine?” interrupted Fiona. “What’s that? A disaster of some kind?”

“You know, Beltaine,” Deimne said, “when you build the big fires and drive the cattle between them.”

The McCools responded with wide-eyed incredulity.

“Beltaine, the most magic night of all, the night when the world goes from darkness to light, from winter to summer,” Deimne went on, continuing to leave the children in total darkness.

“In the morning, after Beltaine,” Deimne said, as if explaining to people suffering from amnesia, “you rush up the hill to greet the sun. You wash in the dew, and you cut branches from the rowan tree and bring them into the house.” (Tannen, 1981, pp. 46-7)

The ritual of driving cattle between two fires at Beltaine is recorded in the 10th-century Sanas Chormaic (“Cormac’s Glossary”) but the rowan branches and the morning dew are much later folklore customs from different “Celtic” areas, such as the Isle of Man and Scotland (see, for example, Rhys, 1910, pp. 308-9; McNeill, 1959, p. 63). The assumption here, once more, by Rhys and other Celticists, and eventually by Tannen, is that there is an unbroken chain of tradition between a 10th-century Irish custom (recorded only in one source) and May Day customs ten centuries later from across the British Isles.

The Lost Legend of Finn[image error] Unsurprisingly, the quarter-day that gets most attention in Tannen’s novels is Samhain. The Wizard Children of Finn follows Finn’s “heroic journey” not from its medieval sources, but as reconstructed (from a variety of manuscripts) and retold in the early 20th century by Lady Gregory in Gods and Fighting Men (1904). Like Gregory, Tannen treats as a climactic event of Finn’s heroic career his defeat of the fire-breathing Aillen, who, every year on Samhain, burns down Temhair, the seat of the High King. The setting of the original story (narrated within the 12th-century Acallam na Senórach, “Dialogue of [or with] the old men”) is indeed Samhain, and Tannen utilises the frequent motif of warfare and feuds pausing to allow the feast of Samhain to take place. However, as the 20th-century Fiona walks with many other “ancient Celts” towards Temhair for the festival, she makes a link with her contemporary Halloween:

Unsurprisingly, the quarter-day that gets most attention in Tannen’s novels is Samhain. The Wizard Children of Finn follows Finn’s “heroic journey” not from its medieval sources, but as reconstructed (from a variety of manuscripts) and retold in the early 20th century by Lady Gregory in Gods and Fighting Men (1904). Like Gregory, Tannen treats as a climactic event of Finn’s heroic career his defeat of the fire-breathing Aillen, who, every year on Samhain, burns down Temhair, the seat of the High King. The setting of the original story (narrated within the 12th-century Acallam na Senórach, “Dialogue of [or with] the old men”) is indeed Samhain, and Tannen utilises the frequent motif of warfare and feuds pausing to allow the feast of Samhain to take place. However, as the 20th-century Fiona walks with many other “ancient Celts” towards Temhair for the festival, she makes a link with her contemporary Halloween:

Fiona […] thought this crowd was nothing compared to what she was used to on Fifth Avenue around Christmas time. She laughed to herself thinking of this same gang parading up Fifth Avenue. There were boys driving pigs, warriors carrying spears, an old man with a cow, a group of barefoot girls singing.

“It looks like a Halloween party,” Fiona said to herself. From what Finn had told her about Samhain, it could be the great-grandfather of their Halloween. It was the right time of year for it, and it was the night the ever-living ones were supposed to come out of the hills of Ireland and go around committing mischief. No human dared step outside on Samhain night. “Like our witches and goblins,” thought Fiona, although the possibility of supernatural beings walking around at night seemed much more real in ancient Ireland than back in New York City. (Tannen, 1981, pp. 170-1, emphasis added).

Tannen, here, is very much taking for granted the idea that “pagan” Samhain is the origin of modern Halloween. Indeed, in the sequel, The Lost Legend of Finn, Bran directly identifies Halloween with Samhain and uses this correlation to transport himself and his sister back to ancient Ireland “on Halloween night” (Tannen, 1982, p. 7).

The Snow Spider[image error] A rather different representation of the Halloween/Samhain equation can be found in Jenny Nimmo’s The Magician Trilogy. In the first book, The Snow Spider[image error]The Snow Spider, Nimmo places two crucial events during Halloween: Gwyn’s birth, and Bethan’s disappearance. Gwyn is a young magician, who has inherited magical power that returns to his family “once in every seven generations” (Nimmo, 2003, p. 13). His birth during the magical, liminal time of Halloween, singles him out as special, but his Nain (Welsh for “grandmother”) also links this date with Gwyn’s ancient heritage:

A rather different representation of the Halloween/Samhain equation can be found in Jenny Nimmo’s The Magician Trilogy. In the first book, The Snow Spider[image error]The Snow Spider, Nimmo places two crucial events during Halloween: Gwyn’s birth, and Bethan’s disappearance. Gwyn is a young magician, who has inherited magical power that returns to his family “once in every seven generations” (Nimmo, 2003, p. 13). His birth during the magical, liminal time of Halloween, singles him out as special, but his Nain (Welsh for “grandmother”) also links this date with Gwyn’s ancient heritage:

‘And are you a witch too, Nain?’ Gwyn ventured.

‘No,’ Nain shook her head regretfully. ‘I haven’t the power, I’ve tried, but it hasn’t come to me.’

‘And how do you know it has come to me?’

‘Ah, I knew when you were born. It was All Hallows Day, don’t forget, the beginning of the Celtic New Year. Such a bright dawn it was; all the birds in the world were singing. Like bells wasn’t it? Bells ringing in the air. Your father came flying down the lane, “The baby’s on the way, Mam,” he cried. He was so anxious, so excited. By the time we got back to the house you were nearly in this world. And when you came and I saw your eyes, so bright, I knew. And little Bethan knew too, although she was only four. She was such a strange one, so knowing yet so wild, sometimes I thought she was hardly of this world; but how she loved you. And your da, so proud he was. What a morning!’ (Nimmo, 2003, pp. 48-9)

The term “Samhain” does not appear at all in the trilogy, and neither does the Welsh name of the same festival, “Calan Gaeaf”. However, it is quite clear that Nimmo, just like Tannen, accepts the popular view that modern Halloween can trace its origins back to a pan-“Celtic” festival of the same date, which also signals the beginning of the “Celtic” year. As we saw above, the claim that Samhain was the “Celtic” New Year is based on very dubious evidence and the Welsh material does not yield any support for this theory.

But Nimmo’s Halloween also seems to be a festival associated with the dead. Bethan, Gwyn’s older sister, disappears in the mountains “the night after Halloween” and her ghostly “double”, a girl who looks exactly like Bethan, only with pale skin and fair hair, returns to the family home via Gwyn’s magic. She is, ostensibly, the ghost of his dead sister. Bethan’s apparent death is linked with the melancholy imagery of modern Halloween, complete with American pumpkin jack-o’-lantern (as opposed to the native turnips used in earlier tradition): “It was the night after Halloween and the pumpkin was still on the windowsill, grimacing with its dark gaping mouth and sorrowful eyes. Bethan had become curiously excited…” (Nimmo, 2003, p. 14). But it is important here to remember, as noted above, that the Halloween association with the dead is a Christian development, following the regularization of All Saints and All Souls feasts on 1 and 2 November respectively. At the same time, Nimmo cannot quite escape its globalized homogenization following Halloween’s evolution in the USA where it travelled with the early immigrants, and was subsequently re-imported to Britain first in the 19th century, and latterly more so through popular culture references.

The Chestnut Soldier (Magician Trilogy (Scholastic))[image error] Halloween is mentioned one more time by Nimmo, in a pivotal moment of the third book in the series: The Chestnut Soldier (Magician Trilogy (Scholastic))[image error]The Chestnut Soldier. Towards the end of the novel, as Gwyn prepares to “merge” with his ancestor Gwydion, the magician from the Mabinogion, in order to exorcise the destructive spirit of Efnisien from Evan Llyr (the eponymous “chestnut soldier”) his Nain notes that the next day is Halloween:

Halloween is mentioned one more time by Nimmo, in a pivotal moment of the third book in the series: The Chestnut Soldier (Magician Trilogy (Scholastic))[image error]The Chestnut Soldier. Towards the end of the novel, as Gwyn prepares to “merge” with his ancestor Gwydion, the magician from the Mabinogion, in order to exorcise the destructive spirit of Efnisien from Evan Llyr (the eponymous “chestnut soldier”) his Nain notes that the next day is Halloween:

When [Gwyn] reached his grandmother’s cottage he found her in the garden, piling leaves ready for a bonfire. ‘Are you coming down tomorrow, then, Gwydion Gwyn?’ she asked. ‘To share my Hallowe’en fire?’

Hallowe’en? He’d forgotten. How appropriate, he thought wryly. But there would be no fire. ‘It’ll rain, Nain,’ he told her, ‘and I’m sorry, but I’ll be busy.’ (Nimmo, 2003, pp. 456-7)

Gwyn is now powerful enough to control the weather and be confident in his own abilities. But he does note the suitability of Halloween as a fitting time for a magical duel. Nain’s mention of a fire is also significant. Folklore collections from the British Isles often include bonfires in Halloween customs, which Davis has linked to Christian iconography, especially after the development of the Catholic doctrine of the purgatory and the symbolic value of the imagery of cleansing by fire (2009, p. 33). But this is one more example of a Christian-related custom that has been projected backwards and has been claimed to have pagan origins. Given the mention of fires at Beltain in Sanas Chormaic (see above) and the later evidence of bonfires on Halloween, Sir James Frazer claimed that Halloween was also a fire-festival, while Charles Hardwick extended this to all four quarter-days, giving rise to the popular idea of all four of them as pan-“Celtic” “fire-festivals” (see Hutton, 1996, pp. 366, 408). Nain’s magical ancestry, and her invitation to Gwyn to “share” her “Halloween fire” (rather than “bonfire”) points to the popular idea of Halloween as remnant of such a “Celtic” “fire-festival”.

As we saw above, Tannen’s novel uses the framework of the four Irish quarter-days, but Susan Cooper’s much-loved The Dark is Rising Sequence seems to be working with the idea of a looser, “Old Religion” calendar, such as the one popularized by Margaret Murray and later endorsed by Robert Graves in The White Goddess (1952). In this schema, the “Old Religion” encompasses the quarter-days of the “Celtic” calendar, but also syncretically merges them with similar festivals from other pre-Christian, “pagan” cultures, and adds the two solstices:

The ancient festivals remained all through, and to them were added the festivals of the succeeding religions. The original celebrations belonged to the May-November year, a division of time which follows neither the solstices nor the agricultural seasons; […] The chief festivals were: in the spring, May Eve (April 30), called Roodmas or Rood Day in Britain and Walpurgis-Nacht in Germany; in the autumn, November Eve (October 31), called in Britain All hallow Eve. Between these two came: in the winter, Candlemas (February 2); and in the summer, the Gule of August (August 1), called Lammas in Britain. To these were added the festivals of the solstitial invaders, Beltane at midsummer and Yule at midwinter… (Murray, 1921, p. 109)

Robert Graves, whose work Cooper definitely read, lists the same range of dates and versions of names of these festivals: “Candlemas, Lady Day, May Day, Midsummer Day, Lammas, Michaelmas, All-Hallowe’en, and Christmas” (1952, p. 24) adding “Samhain” as an alternative name to “All Souls’ Eve” (p. 103) and “Lugh nasadh” as an alternative name for “Lammas” (p. 301).

In Cooper’s reflections on the genesis of the Dark Is Rising Sequence (especially on the moment when she realized that Over Sea, Under Stone would fit into a longer fantasy series with The Dark is Rising as the second book) she notes:

So I took a piece of paper and wrote down the names of all five books, their characters, the places where they would be set, and the times of the year. The Dark Is Rising would be at the winter solstice and Christmas, the next book Greenwitch would be in the spring, at the old Celtic festival of Beltane… (Cooper, 2017)

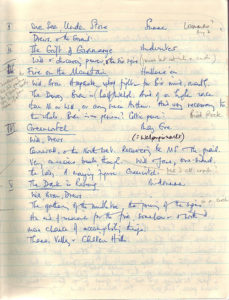

Susan Cooper’s manuscript “plan” for The Dark is Rising sequence – click on the image to see a larger photo from Cooper’s website, www.thelostland.com

This actual piece of paper has been made available by Cooper on her website (2017), and shows that her reminiscences of these early ideas are indeed structured around significant days of the British (and more generally North-Western European) calendar, very much agreeing with the dates and names given by Murray and Graves. I have reproduced Cooper’s (then) projected book titles and the dates she attached to them in her “plan” in the table below:

I. Over Sea, Under Stone

Summer Lammas? Aug 2

II. The Gift of Gramarye (eventually titled The Dark is Rising)

Mid-winter

III. Greenwitch

May Eve (=Walpurgisnacht)

III. Fire on the Mountain (eventually titled The Grey King)

Hallowe’en

V. The Dark is Rising (eventually titled Silver on the Tree)

Midsummer

In the Sequence, therefore, the four “Celtic” feasts fit seamlessly within the more genera pre-Christian, “pagan” scheme popularized by Murray and Graves (and later taken up by the emerging Wicca movement) and definitely form an underlying “substratum” to the Christian festivals and rituals of the Sequence’s modern setting. This is especially apparent in the second book of the series, The Dark is Rising, in which Christmas celebrations are a rather superficial layer, while deeper significance is given to the “pagan” winter solstice, which is presented as more authentic, primeval and “natural”; the “Old Religion” indeed, still clinging to the landscape of Britain.

The Dark Is Rising: Modern Classic[image error] The Sequence refers specifically to two of the feasts popularly considered as “pan-Celtic”, Samhain and Beltain. The latter is only referenced once in The Dark Is Rising: Modern Classic[image error]The Dark is Rising, when Will is told by Merriman to “look into the fire” and “make it his friend”:

The Sequence refers specifically to two of the feasts popularly considered as “pan-Celtic”, Samhain and Beltain. The latter is only referenced once in The Dark Is Rising: Modern Classic[image error]The Dark is Rising, when Will is told by Merriman to “look into the fire” and “make it his friend”:

Wondering, Will moved forward as if to warm himself, and did as he was told. Staring at the leaping flames of the enormous log fire in the hearth, he ran his fingers gently over the Sign of Iron, the Sign of Bronze, the Sign of Wood, the Sign of Stone. He spoke to the fire, not as he had done long ago, when challenged to put it out, but as an Old One, out of Gramarye. He spoke to it of the red fire in the king’s hall, of the blue fire dancing over the marshes, of the yellow fire lighted on the beacon hills for Beltane and Hallowe’en; of wildfire and need-fire and the cold fire of the sea; of the sun and of the stars. The flames leaped. (Cooper, 2010, p. 417-8, emphasis added)

The Grey King (The Dark Is Rising)[image error] Here Cooper imaginatively responds to the idea of the “Celtic” quarter-days as “fire-festivals”, taking for granted the erroneous extension of the Beltaine fires to Samhain/Halloween. But, of course, “fire on the mountain” is also very much at the centre of the plot of The Grey King (The Dark Is Rising)[image error]The Grey King, which is set on Halloween. Already at the end of Greenwitch, the prophecy the Drew children and Will Stanton discover on the Grail makes reference to “the day of the dead, when the year too dies” (Cooper, 2010, p. 620). When Will and Bran try to solve this riddle, the following dialogue ensues:

Here Cooper imaginatively responds to the idea of the “Celtic” quarter-days as “fire-festivals”, taking for granted the erroneous extension of the Beltaine fires to Samhain/Halloween. But, of course, “fire on the mountain” is also very much at the centre of the plot of The Grey King (The Dark Is Rising)[image error]The Grey King, which is set on Halloween. Already at the end of Greenwitch, the prophecy the Drew children and Will Stanton discover on the Grail makes reference to “the day of the dead, when the year too dies” (Cooper, 2010, p. 620). When Will and Bran try to solve this riddle, the following dialogue ensues:

‘I was thinking,’ Will said, ‘that the day of the dead might be All Hallows’ Eve. Don’t you think? Hallowe’en, when people used to believe all the ghosts walked.’

‘I know some who still believe they do,’ Bran said. Things like that last a long time, up here. There is one old lady I know puts out food for the spirits, at Hallowe’en. She says they eat it too, though if you ask me it is more likely the cats, she has four of them… Hallowe’en will be this next Saturday, you know.’

‘Yes,’ Will said. ‘I do know. Very close.’

‘Some people say that if you go and sit in the church porch till midnight on. Hallowe’en, you hear a voice calling out the names of everyone who will die in the next year,’ Bran grinned. ‘I have never tried it.’

But Will was not smiling as he listened. He said thoughtfully, ‘You just said, in the next year. And the verse says, “On the day of the dead when the year too dies.” But that doesn’t make sense. Hallowe’en isn’t the end of the year.’

‘Maybe once upon a time it used to be,’ Bran said. ‘The end and the beginning both, once, instead of December. In Welsh, Hallowe’en is called Calan Gaeaf, and that means the first day of winter…’ (Cooper, 2010, pp. 660-1, emphasis in the original)

Here Cooper interposes local Welsh folklore with ideas about the ancient “Celtic” year. On the one hand, she presents local superstitions and rituals, such as sitting at the church yard on Halloween to find out who will die during the next year. This agrees nearly point-by-point with Marie Trevelyan’s account of such a belief in her Folk-lore and folk-stories of Wales:

If you sit in the church porch at midnight on Hallowe’en, or all through the night, you will see a procession of all the people who are to die in the parish during the year, and they will appear dressed in their best garments. (1909, p. 254)

Silver On The Tree (The Dark Is Rising)[image error] But, on the other hand, we have in the words of Will and Bran once more the popular idea of Halloween as the “Celtic” (or at least, “pagan”, pre-Christian) New Year, as well its link with the dead as part and parcel of the supposed “pagan” origins of the festival, rather than its Christian guise. In Silver on the Tree, Bran makes the case of a pan-“Celtic” festival even stronger. Asked by the Drew children exactly how long he had known Will , Bran’s replied: “Calan Gaeaf last year, I got to know Will. Last Samain. If you can work that out, you’ll know how long” (Cooper, 2010, p. 876). Here the Welsh and Irish names of this seasonal festival are treated as interchangeable, and this knowledge singles out Will and Bran from the Drew children, who Bran still perceives as “English” and “ignorant” at this point in the story. On the contrary, Will, as an Old One, and Bran as the son of King Arthur, are in the know – they are, themselves, remnants of the “Old Religion” of Murray’s and Graves’s evocations.

But, on the other hand, we have in the words of Will and Bran once more the popular idea of Halloween as the “Celtic” (or at least, “pagan”, pre-Christian) New Year, as well its link with the dead as part and parcel of the supposed “pagan” origins of the festival, rather than its Christian guise. In Silver on the Tree, Bran makes the case of a pan-“Celtic” festival even stronger. Asked by the Drew children exactly how long he had known Will , Bran’s replied: “Calan Gaeaf last year, I got to know Will. Last Samain. If you can work that out, you’ll know how long” (Cooper, 2010, p. 876). Here the Welsh and Irish names of this seasonal festival are treated as interchangeable, and this knowledge singles out Will and Bran from the Drew children, who Bran still perceives as “English” and “ignorant” at this point in the story. On the contrary, Will, as an Old One, and Bran as the son of King Arthur, are in the know – they are, themselves, remnants of the “Old Religion” of Murray’s and Graves’s evocations.

The last and most recent Celtic-inspired text that makes an interesting use of the “Celtic” quarter-days is Henry Neff’s The Tapestry series. Neff’s main protagonist, Max MacDaniels, is a creative reshaping of Cuchulainn from Irish medieval literature, and there is a clear Irish strand in the large canvas of Neff’s world-building. Similar to Cooper, Neff has a larger vision of a looser calendar that syncretically combines “pagan” festivals with Christian and later folkloric ones. In The Hound of Rowan we first see Max using body amplification and starting to be conscious of his abilities on All Hallows Eve (for which Neff uses the term Samhain in later books). In The Second Siege, Max and David fly aboard the Kestrel to the otherworldly Sidh on Christmas Eve, close to the winter solstice. In The Fiend and the Forge Max and David attack Astaroth on Walpurgisnacht, the same date as the eve of Beltaine. In The Red Winter Astaroth attempts to open a portal to an other world on Imbolc; while Max finally departs for the Sidh on Midsummer. Again, rather expectedly, Halloween/All Hallows’ Eve/the Feast of Samhain (called interchangeably with these names) features much more heavily in the series than any of the other festivals, and its syncretic nature is emphasized in the third book, The Fiend and the Forge (Tapestry (Paperback)) (Tapestry (Yearling Books))[image error]The Fiend and the Forge:

By the early evening, it was time to prepare for the Samhain Feast, and Max’s attention shifted to the pressing issue of his costume. At Rowan, the celebration was officially called the Samhain Feast in memory of Solas, but the residents actually called this stretch of the calendar whatever they liked: Halloween, All Saint’s Day, Día de los Muertos, Dia de Finados, Feralia. Whatever the holiday, costumes were a common tradition to honor the dead, chase away evil spirits, and celebrate the harvest. (Neff, 2010, p. 200)

The Fiend and the Forge (Tapestry (Paperback)) (Tapestry (Yearling Books))[image error] Neff does not invoke the idea of Halloween/Samhain as the “Celtic” New Year, but he does associate it clearly with the dead, and he mentions more – mostly American – festivals taking place during the same period that share this concern for dead: the Mexican Día de los Muertos (31 October – 2 November), and the Brazilian Dia de Finados (2 November). Feralia is rather different: it was a Roman festival celebrating the spirits of the dead, but it took place in February, rather than October-November. Neff is clearly here catering for an American readership, but he is also highlighting the multi-cultural aspect of his fantasy world: just like he blends mythological motifs from various traditions (including Irish, Greek and Roman, Egyptian, Hebrew, Finnish and Anglo-Saxon) he also allows for this hybridization of festivals and beliefs. However, in the parallel world of the Sidh, a version of mythical Ireland to which Max travels to be trained by Scathach, the female warrior that trained CuChulain, the festivals observed are very much the specific Irish quarter-days as they appear in medieval Irish literature. While staying in the Sidh Max is asked to build “bonfires for Beltaine” (Neff, 2014, chap. 5) and he also attends the Samhain and Imbolc festivals. The Samhain celebration includes “feasting in Hearth Hall” and “listening to songs of the faerie folk in Summervyne” (ibid.), while Imbolc is described as “a day for feasting and celebrating the upcoming spring” (Neff, 2014, chap. 24).

Neff does not invoke the idea of Halloween/Samhain as the “Celtic” New Year, but he does associate it clearly with the dead, and he mentions more – mostly American – festivals taking place during the same period that share this concern for dead: the Mexican Día de los Muertos (31 October – 2 November), and the Brazilian Dia de Finados (2 November). Feralia is rather different: it was a Roman festival celebrating the spirits of the dead, but it took place in February, rather than October-November. Neff is clearly here catering for an American readership, but he is also highlighting the multi-cultural aspect of his fantasy world: just like he blends mythological motifs from various traditions (including Irish, Greek and Roman, Egyptian, Hebrew, Finnish and Anglo-Saxon) he also allows for this hybridization of festivals and beliefs. However, in the parallel world of the Sidh, a version of mythical Ireland to which Max travels to be trained by Scathach, the female warrior that trained CuChulain, the festivals observed are very much the specific Irish quarter-days as they appear in medieval Irish literature. While staying in the Sidh Max is asked to build “bonfires for Beltaine” (Neff, 2014, chap. 5) and he also attends the Samhain and Imbolc festivals. The Samhain celebration includes “feasting in Hearth Hall” and “listening to songs of the faerie folk in Summervyne” (ibid.), while Imbolc is described as “a day for feasting and celebrating the upcoming spring” (Neff, 2014, chap. 24).

Neff is clearly aware of the potential of festivals from different traditions to serve as loci of the supernatural, especially within the fantasy genre, where strict rules are needed to limit the temptation of solving every problem through random magic (see Fimi, 2016). Interestingly, the one Irish festival not used in The Tapestry is Lughnasadh. When I interviewed Neff last year, I said that I had expected the final episode in Max’s heroic journey to occur during Lughnasadh, rather than Midsummer. Neff explained:

As far as Max’s departure date is concerned, I chose Midsummer because it’s an occasion that is commonly associated with faeries and magic. In retrospect, Lughnasadh — although less well known — would have been particularly fitting for the son of Lugh Lámhfhada. (cited in Fimi, 2016)

This comment is, for me, a reminder of the caveat with any study such as this one: writing fantasy literature isn’t the same as writing a research paper on “Celtic” religion or folklore. At the end of the day, artistic decisions are mostly based on aesthetic considerations rather than a concern for authenticity or evidence-based research. Nevertheless, by creatively reshaping their own, individual versions of the “Celtic” past, each of the fantasy authors examined in this essay (and in my monograph) feed into the cultural processes that inform popular perceptions of “Celticity”. In the case of the four “Celtic” quarter-days, or “fire festivals”, and especially Samhain/Halloween, they contribute to wider popular beliefs about “pagan” survivals in modern culture.

Works Cited

Cooper, Susan (2010) The Dark Is Rising: The Complete Sequence. London: Margaret K. McElderry Books.

Cooper, Susan (2017) Interview, available at: http://www.thelostland.com/about/interview.html

Davis, Robert A. (2009) “Escaping Through Flames: Halloween as a Christian Festival”, in Foley, M. and O’Donnell, H. (eds.) Trick or Treat: Halloween in a Globalising World. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 28-44.

Fimi, Dimitra (2016) An Interview with Henry Neff: Celtic Myth, Liminal Times and Fantastic Creatures, available at: http://dimitrafimi.com/an-interview-with-henry-neff-celtic-myth-liminal-times-and-fantastic-creatures/

Fimi, Dimitra (2017) Celtic Myth in Contemporary Children’s Fantasy: Idealization, Identity, Ideology. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Frazer, Sir James (1906-15) The Golden Bough, 12 vols. London: Macmillan.

Graves, Robert (1952) The White Goddess: A Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth. Third Edition, amended and enlarged. London: Faber and Faber.

Hutton, Ronald (1996) The Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kinsella, Thomas (1969) (trans.) The Táin. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Leerssen, Joep. (1996) “Celticism”, in Brown, Terrence (ed.) Celticism, Amsterdam: Rodopi, pp. 1-20.

Löffler, Marion (2006) “Celticism”, in Koch, John T. (ed.) Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia, Vol. I, Santa Barbara; Oxford: ABC-Clio, pp. 387-9.

Mcneil, F. Marian (1959) The Silver Bough, Vol. 2: A Calendar of Scottish National Festivals. Candlemass to Harvest home. Glasgow: MacLellan.

Minard, Antone (2006) “Coligny calendar”, in Koch, John T. (ed.) Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia, Vol. III, Santa Barbara; Oxford: ABC-Clio, pp. 463-5.

Murray, Margaret Alice (1921) The Witch-Cult in Western Europe: A Study in Anthropology. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Neff, Henry H. (2007) The Hound of Rowan. New York: Random House.

Neff, Henry H. (2008) The Second Siege. New York: Random House.

Neff, Henry H. (2010) The Fiend and the Forge. New York: Random House.

Neff, Henry H. (2012) The Maelstrom. New York: Random House.

Neff, Henry H. (2014) The Red Winter. New York: Random House [Kindle edition].

Nimmo, Jenny (2003) The Snow Spider, The Snow Spider Trilogy. London: Egmont.

Roud, Stephen (2008) The English Year: A Month-By-Month Guide to the Nation’s Customs and Festivals, from May Day to Mischief Night. London: Penguin.

Tannen, Mary (1981) The Wizard Children of Finn. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Tannen, Mary (1982) The Lost Legend of Finn. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Trevelyan, Marie (1909), Folk-lore and Folk-stories of Wales. London: E. Stock.

Turner, Victor W. (1967) “Betwixt and Between: The Liminal Period in Rites de Passage”, in The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual. NY: Cornell University Press, pp. 93-111.

Van Gennep, Arnold (1960) The Rites of Passage. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Notes

The reference to “Brón Trogain” in Tochmarc Emire is unusual; most other medieval Irish texts use “Lughnasadh” for this fourth festival.

The feast of All Saints is also known as All Hallows’ Day, or Hallowmas, so All Hallows Eve became contracted as Hallowe’en.

It was, in fact, “resisted for more than a generation” in Ireland, where the Church showed preference for the older date of 20 April (Davis, 2009, p. 32).

E.g. in the tale of “Culhwch ac Olwen”, Gwyn son of Nudd and Gwythyr son of Greidol fight for the maiden Creiddylad every May day until Judgement Day.

In fact, Cooper wanted Fire on the Mountain as the title of this fourth book in the series, but had to scrap this idea because the title had already been used recently for a collection of Ethiopian folktales (see Fimi, 2017, 255).

October 20, 2019

Tolkien’s Glittering Caves of Aglarond and Cheddar Gorge and Caves in Somerset

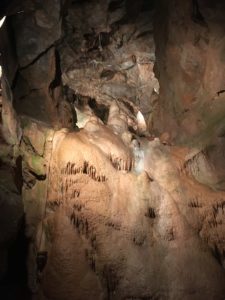

Last month, I visited Cheddar Gorge and Caves, together with my husband and young son. This trip had been “on the list” for many years, and I am grateful to my colleague and fellow Tolkien scholar Dr Kristine Larsen for giving me a gentle nudge to just get on with it!

The reason I’ve always wanted to go, of course, is the Tolkien connection: the caves at Cheddar Gorge are one of the few places in the UK that Tolkien acknowledged as a direct inspiration for a location in Middle-earth: the “glittering caves” of Aglarond, i.e. the caverns of Helms Deep. In a 1971 letter to P. Rorke, who had commented on Tolkien’s famous description (by way of Gimli’s eulogy) of the caves, Tolkien wrote:

I was most pleased by your reference to the description of ‘glittering caves’. No other critic, I think, has picked it out for special mention. It may interest you to know that the passage was based on the caves in Cheddar Gorge and was written just after I had revisited these in 1940 but was still coloured by my memory of them much earlier before they became so commercialized. I had been there during my honeymoon nearly thirty years before. (Letter 321)

Needless to say, I set off on my visit with Gimli’s famous passage, extolling the virtues of the Glittering Caves of Aglarond, fresh in my mind. What I found out pretty soon was that Gimli’s description seems to follow the visitor’s trail in Gough’s cave (the biggest of the two caves at the site), beginning with the memory of walking from chamber to chamber, seeing small marvels first, and culminating with the much more spectacular sites further in.

Gimli begins his speech, addressed to Legolas, with these words:

“Strange are the ways of Men, Legolas! Here they have one of the marvels of the Northern World, and what do they say of it? Caves, they say! Caves! Holes to fly in time of war, to store fodder in! My good Legolas, do you know that the caverns of Helm’s Deep are vast and beautiful? There would be an endless pilgrimage of Dwarves, merely to gaze at them, if such things were known to be. Aye indeed, they would pay pure gold for a brief glance!” (The Lord of the Rings, The Two Towers, Book III, “The Road to Isengard”).

Gimli also mentions the “immeasurable halls” of the caves, and towards the end of his speech he notes the succession of halls and chambers, the one following the other, which is very much the experience of a visitor entering Gough’s cave. The first remarkable features of the caves Gimli mentions are “veins of precious ore” which “glint in the polished walls”, very much chiming with Photos 1, 2, and 3 below, all taken in the first few chambers of Gough’s cave (with a smartphone, I hasten to add, so passable quality, but I can only imagine what can be done with a professional camera and proper expertise!).

Gimli continues with a description that brings to mind the “organ” in the chamber called “St Paul’s Cathedral” (Photo 4), as Gough’s cave now begins to reveal some of its most marvellous parts:

Photo 4: “St Paul’s Cathedral”, Gough’s Cave, Cheddar Gorge and Caves

and the light glows trough folded marbles, shell-like, translucent as the living hands of Queen Galadriel. There are columns of white and saffron and dawn-rose, Legolas, fluted and twisted into dreamlike forms; they spring up from many-coloured floors to meet the glistening pendants of the roof: wings, ropes, curtains fine as frozen clouds; spears, banners, pinnacles of suspended palaces!” (The Lord of the Rings, The Two Towers, Book III, “The Road to Isengard”)

The rock formations in Photo 4 looked like they matched exactly Gimli’s description, especially their “white and saffron and dawn-rose” colourings, “translucent as the living hands of Queen Galadriel” (there is an apt comparison with fingers when looking at these stalactites, I think).

Especially the mention in this extract of the stalagmites (“spring[ing] up from many-coloured floors”) and the stalactites (“to meet the glistening pendants of the roof”) bring to mind the first pool one sees in Gough’s cave (Photo 5), just before reaching “St Paul’s Cathedral”, which features both stalactites and stalagmites, as well as “curtains” (also known as “draperies”), a technical term to refer to thin, wavy sheets of calcite hanging downward (see Photo 6, which highlights this detail of Photo 5).

And as one turns around the corner in “St Paul’s Cathedral” another marvel awaits, the small grotto affectionately called: “Aladdin’s Cave” (see Photo 7, the only one taken by my husband with his much better-quality camera, and Photo 8, with my son looking in, for scale). This particular site seems to match Gimli’s words immediately after the extract above:

Photo 7: Aladdin’s Cave, Gough’s Cave, Cheddar Gorge and Caves. Photo credit: Andrew Davies

“Still lakes mirror them: a glimmering world looks up from dark pools covered with clear glass; cities, such as the mind of Durin could scarce have imagined in his sleep, stretch on through avenues and pillared courts, on into the dark recesses where no light can home. And plink! a silver drop falls, and the round wrinkles in the glass make all the towers bend and waver like weeds and corals in the grotto of the sea. Then evening comes: they fade and twinkle out; the torches pass on into another chamber and another dream.” (The Lord of the Rings, The Two Towers, Book III, “The Road to Isengard”)

Photo 8: Aladdin’s Cave, Gough’s Cave, Cheddar Gorge and Caves

To be honest, this particular spot in Gough’s cave was, for me, the most memorable and most beautiful to look at – my family and I stayed in that chamber for a bit, looking into the grotto, and trying to capture its beauty (no photo does it justice!!!). In the few instances where there was silence (literally, only for 1-2 seconds at a time, as it was a busy weekend at Cheddar) one could just about hear the “plink” of drops falling in the pool, but seeing the ripples in the water and the distortion of the reflected rock formations was indeed very much reminiscent of Tolkien’s description. The big difference, of course, is that Aladdin’s cave is a miniature world, but Tolkien’s description literally enlarges its most spectacular qualities to an entire chamber.

I even tried a short video, in an effort to capture a better sense of the depth and complexity of “Aladdin’s cave” (but alas, no total silence so the sound is disappointing):

Further in, there are more amazing chambers and much bigger spectacular rock formations, such as the “Diamond Chamber” (Photo 9), a beautiful tree-like structure, with stalactites looking like extended roots (Photo 10) and a stalactite “waterfall” (Photo 11), but I think most of the features in Gimli’s description fit better with the chambers and features I identified further up.

The closing of Gimli’s speech brings us back to a contemplation of the overall magnificence of the caves:

There is chamber after chamber, Legolas; hall opening out of hall, dome after dome, stairs beyond stairs; and still the winding paths lead on into the mountains’ hearth. Caves! The Caverns of Helm’s Deep! Happy was he chance that drove me there! It makes me weep to leave them!” (The Lord of the Rings, The Two Towers, Book III, “The Road to Isengard”)

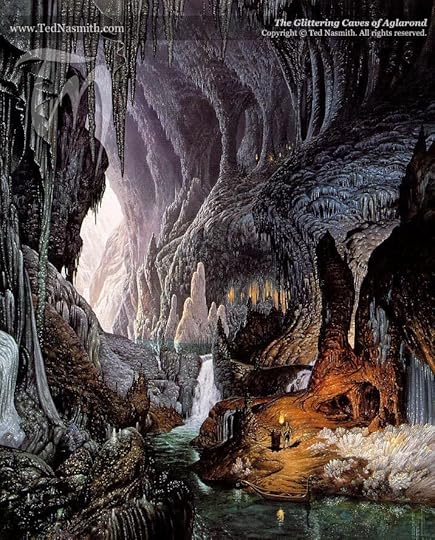

There is only one visual representation of these Middle-earth caves in Tolkien art that I know of, and that’s Ted Nasmith’s wonderful “The Glittering Caves of Aglarond” (see below), picturing Gimli and Legolas visiting the caves, presumably after the events of The Lord of the Rings. As we find out in the Appendices:

The Glittering Caves of Aglarond, by Ted Nasmith, reproduced with kind permission

After the fall of Sauron, Gimli brought south a part of the Dwarf-folk of Erebor, and he became Lord of the Glittering Caves. He and his people did great works in Gondor and Rohan. For Minas Tirith they forged gates of mithril and steel to replace those broken by the Witch-king. Legolas his friend also brought south Elves out of Greenwood, and they dwelt in Ithilien, and it became once again the fairest country in all the westlands. (The Lord of the Rings, The Return of the King, Book VI, Appendix A)

Nasmith’s illustration must be catching the moment when half of the bargain between Gimli and Legolas, struck immediately after Gimli’s lengthy eulogy of the glittering caves, is fulfilled:

‘You move me, Gimli,’ said Legolas. ‘I have never heard you speak like this before. Almost you make me regret that I have not seen these caves. Come! Let us make this bargain – if we both return safe out of the perils that await us, we will journey for a while together. You shall visit Fangorn with me, and then I will come with you to see Helm’s Deep.’

‘That would not be the way of return that I should choose,’ said Gimli. ‘But I will endure Fangorn, if I have your promise to come back to the caves and share their wonder with me.’ (The Lord of the Rings, The Two Towers, Book III, “The Road to Isengard”)

It was a pleasure to fulfil a promise to myself, as a Tolkien scholar, to visit Cheddar Gorge and Caves and to “share their wonder” with my family! For more information on visits, opening times, planning a trip, etc. see the official Cheddar Gorge and Caves site here: https://www.cheddargorge.co.uk/

September 4, 2019

Tiny Alice and Miniature Books Exhibition – July-September 2019

This summer, a very exciting project I have been working on for a while was launched, and I curated my first exhibition to accompany and complement it. The launch itself was an overwhelming moment, with a lot of media attention and too much excitement, so it’s only now that I can look back and reflect, and while the exhibition is still on show, that I am ready to blog about it.

Are you sitting comfortably? Here it goes! For a quick intro, click first on the video below!

A tiny reproduction of #AliceInWonderland has been created by UofG’s @Dr_Dimitra_Fimi & @darylbeggs of @cardiffuni

August 23, 2019

Tolkien at IMC Leeds 2019 – round-up

It’s taken a bit longer than usual this year, but this is my brief report on an outstanding series of papers and a roundtable discussion on Tolkien at the International Medieval Congress 2019 at Leeds in early July 2019. This overview of all presentations is based on my live-tweeting during the sessions, so you will find a link to the relevant twitter thread under each session title. Just like last year, I should warn you that my reporting of the papers is uneven at best, and doesn’t always reflect the richness and depth of each individual presentation (often because I got engrossed in an interesting argument and forgot to tweet!) But at least readers will get a flavour of the scope and range of topics covered. I also should say that all the Tolkien sessions were once more very well attended, and this year the IMC had given us nice, spacious rooms!

Last but not least, during this year’s business meeting, I announced that – after five years – I am stepping down from organizing the Tolkien at Leeds sessions. It’s time for someone else to benefit from this experience, and I am pleased to pass the baton to my former PhD student and co-editor Dr Andrew Higgins. For CFP for Tolkien at Leeds 2020 see here.

1st #Tolkien session @IMC_Leeds: “Materiality in Tolkien’s Medievalism, I”

https://twitter.com/Dr_Dimitra_Fimi/status/1145639002428588034

First up: Kristine Larsen on “Medieval Automata and J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Fall of Gondolin”

Larsen is talking us through the sort-of-mechanical dragons in the Fall of Gondolin. Are they mechanistic dragons? Surreal hybrids of beast and machine? Are they related to WWI tanks?

Larsen: In Melkor’s fires foreground Saruman’s reliance on the machine – resonances of the Industrial Revolution and related philosophical perspectives.

Larsen: before Ilúvatar accepts them, Aule’s dwarves are a kind of automaton. Idea of automata going back to classical tradition – Talos is a paradigmatic example.

Larsen now takes us through medieval automata and the tensions they embody: between technology and sorcery/demonic forces. Melkor’s dragons in Gondolin fit well within this model.

Larsen: including models of medieval designs of dragon-like vehicles! (1430, Kyeser’s Bellifortis)

Larsen argues that this is the point of Tolkien’s mechanised dragons in Gondolin: they navigate the dichotomies between nature/machine, magic/technology, the medieval and the modern.

2nd speaker: Deidre Dawson on “Tolkien as Letter-Writer”.

Dawson begins by explaining that the well-known edition of #Tolkien’s letters represents only a fraction of his letter-writing practice.

Dawson recounts anecdotes of Tolkien as a prolific letter-writer, which – despite apologies for delays in respoding and for brevity (!) – often were thousands of words long!

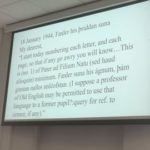

Dawson: Tolkien talked about the “appalling mass of letters” he received – but still took every letter seriously, especially those from children + older people. (Images of letter to a young reader, reproduced in the Bodleian exhibition volume)

Dawson: during WWII #Tolkien used airgrams to correspond with his son Christopher – they would have looked like this (and Tolkien had to be concise!)

Dawson: Tolkien loved using his Hammond typewriter – he started using it more for letters as his hands couldn’t cope with writing that many letters anymore. He also used Latin + Old English in his letters to Christopher -a way to deal with wartime censorship?

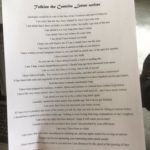

Dawson: there are a number of letters in Carpenter’s edition that were never sent – self-censorship! See also Dawson’s handout with a selection of quotes of #Tolkien as a contrite letter-writer!

3rd speaker: Andrew Higgins on “I glin grandin a Dol Erethrin Airi: An Exploration of Tolkien’s ‘Heraldic Devices of Tol-Erethrin’”. Higgins will be focusing on #Tolkien’s early heraldic devices.

Higgins: these heraldic devices are collectively called “I glin grandin” – the attractive towns? But could have Tolkien forgotten the mutation in “glin”? Could it be “clin”? Could it be “the resounding towns?

Higgins: the devices themselves were linked with specific locations significant to #Tolkien at the time he was working on the Lost Tales. Tau(v)robel: Great Haywood in Staffordshire (notice the bridge connection!)

Higgins: Cor-Tirion = Warwick (where #Tolkien and Edith got married). Celbaros = Cheltenham (where #Tolkien and Edith re-united after a 3-year separation).

Higgins: placement of devices on the page – from bottom to top the progression of #Tolkien’s relationship with Edith, while at the same time chronicling parts of his (then evolving) history of the elves/fairies in The Book of Lost Tales.

2nd #Tolkien session @IMC_Leeds: “Materiality in Tolkien’s Medievalism, II”

https://twitter.com/Dr_Dimitra_Fimi/status/1145683640870932480

First up: Gaëlle Abaléa on “Corpses, Tomb, and Barrows: The Materiality of Death in Tolkien”

How are people in Middle-earth dealing with death? Abaléa is drawing upon Louis-Vincent Thomas’s “Les Chairs de la mort” in her analysis.

How do the Rohirrim and the men of Gondor face death differently? Glorious/heroic death for the former – buried in mounds outside the city. The latter: tradition of ship building and ship burials (my book was referenced on this point!

May 16, 2019

TLS review of Dome Karukoski biopic “Tolkien”

It was great fun to review a film, for a change, though it was very much in keeping with one of the main strands of my blog: Dome Karukoski’s biopic Tolkien.

I went into the cinema thinking about two words: “Tolkien” and “biopic”. The former, the name of the author who has been the main focus of my academic career so far. The latter, a term bringing together film and biography, implying a marriage of fact and fiction. I found myself in split personality mode while watching the film. There were moments when I poked my poor husband next to me and whispered: “this isn’t right!”. And yet, there were moments when I was entertained, and charmed, and even moved to tears. In my TLS review I am similarly attempting to navigate the meanders of accuracy, invention, fact, fiction, creative license, and truth.

You can read the review online here (subscription needed): https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/private/linguistics-mythology-and-tea/

May 12, 2019

A time-traveling cat fantasy: Lloyd Alexander’s Time Cat

I’ve been threatening with a blog post about a time-traveling cat for a while now, so here it is! I’m giving you Lloyd Alexander’s children’s fantasy Time Cat: The Remarkable Journeys of Jason and Gareth, what we’d probably call a middle grade novel today, originally published in 1963, and very much still in print, though not as well-known in the UK as (I suspect) in the USA. This was an important book for Alexander’s career as a children’s fantasy author. It came before the Prydain books, and helped him find his voice and confidence to write for children. I got interested in this book while researching my latest monograph, Celtic Myth in Contemporary Children’s Fantasy, because of the way it paved the way for Prydain – but more on this below!

Time Cat is the story of a cat, Gareth, and his human, a boy named Jason. The “mythology” of this novel is that the human folk belief that cats have nine lives isn’t quite right. As Gareth explains:

“I only have one life. With a difference… I can visit nine different lives. Anywhere, any time, any country, any century.” (p. 3)

and Gareth justifies this in terms familiar to any cat owner:

“Where do you think cats go when you’re looking all over and can’t find them?… And have you ever noticed a cat suddenly appear in a room when you were sure the room was empty? Or disappear, and you can’t imagine where he went?” (p. 3)

And, as one would expect, Gareth and Jason depart on a time-travel journey to visit nine different historical moments all over the world, in a tour clearly curated by Gareth, as all the times and places they visit have a significance for feline-human relationships!

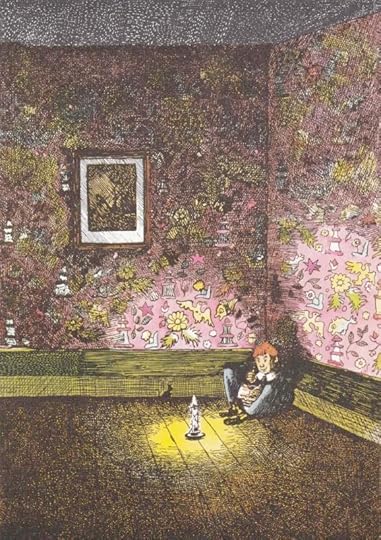

Bastet/Ubastu

The first place they visit is ancient Egypt, circa 2700 B.C., where cats are worshipped as part of the cult of Ubaste (or Bastet), who often appears iconographically as cat-headed. Ubaste’s symbols include the ankh, a hieroglyphic usually associated with word for “life”, which makes Gareth extra special – we learn right at the opening of the novel that Gareth is black, and that the only white spot on his chest is “a T-shaped mark with a loop over the crossbar” (p. 2), which is very clearly an ankh (see also Gareth as pictured in one of the book’s covers, in figure …). Gareth and Jason are whisked away to King Neter-Khet, who has been looking for a special cat to please him. After some misunderstandings, they both end up teaching the king that “Not even a Pharaoh can give orders to a cat” (p. 21) – and rightly so!

Their next visit is to Rome and Britain, in 55 B.C. In Rome Gareth becomes the mascot of the “Old Cats Company” and with Jason and two Roman soldiers they sail to Gaul and from there to Britain. In the conflict between the Roman legions and the “shouting Britons” (p. 33) Gareth gets into a fight with a British wildcat and Jason is captured by a local tribe. They stay with them a while and after they educate the British to value, rather than fear, cats, the wild cat approaches the village with its kittens, one of which is clearly Gareth’s! This is the beginning of domesticated cats in Britain! (So an aetiological story, of sorts!)

Ireland in 411 A.D. is the setting of the next episode: Gareth and Jason meet Diahan, the daughter of a local king, and Sucat, the king’s herdsman. This is the episode mentioned in my book, because Sucat, a slave captured from Wales, and a Christian in a pagan land, is actually a young St Patrick!

Lloyd Alexander has originally planned a Welsh episode for this book, in which Jason and Gareth would meet St Patrick in his native Wales, before his kidnapping by Irish slave raiders. Alexander had been to Wales while serving in WWII and remembered it fondly. Also, while researching Time Cat, he had found out that St Patrick’s Welsh name meant “Good Cat” which tied up nicely with a feline-focused story. According to Alexander’s plan:

Jason and Gareth run across this young boy with a strange name, the future St. Patrick, of course. They meet him in Wales, probably in some spot where I had been myself. I can draw on my own sense of the country because I know it and am fond of it. What could be more natural than this?… They all get kidnapped by these Irishmen in a big dramatic scene… (cited in Jacobs, 1978, p. 264)

The “Welsh research” Alexander embarked upon to prepare this episode was somewhat overwhelming and brought back memories of his childhood reading and his own visit to Wales. As he noted in an interview:

something began stirring inside my head. Strange, personal stirrings began to happen to me. This was far too rich a thing to do in one chapter, so I changed my idea. Instead of having Jason and Gareth meet St. Patrick in Wales, they meet him in Ireland and it becomes an Irish episode. (Ibid., p. 265)

And, indeed, all of the rich Welsh legends Lloyd Alexander has suddenly remembered found their way into the Prydain books (more on which in my book).

As for the name Sucat and its feline associations, in Time Cat St Patrick explains that:

“In Britain, they called me Patrick. But my real name is Sucat. It means ‘Good Cat’ – and it means ‘Good Warrior.’ For in my land, the land of Wales,” he added, “we call our warriors ‘Cats.’” (p. 53)

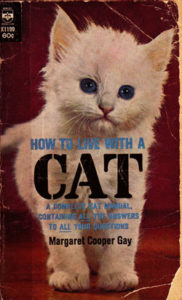

“Succetus” is indeed recorded as one of St Patrick’s alternative names in Tírechán’s Collectanea (Account of St Patrick’s churches) from c. 670. The text itself translates what seems to be a British/Welsh name as “god of war” (see Dumville, 1993, p. 90). The somewhat fanciful translation of the name Patrick as “good cat” came from a book the name of which Alexander could no longer recall, but I’m now pretty sure it was Margaret Cooper Gay’s How to Live with a Cat (first published in 1946), in which she claims that St Patrick was originally “a Scottish monk named Su Cat” which may be translated as “Happy Warrior or the Good Cat” (Cooper Gay, 1969, p. 17). This example of Alexander repeating or adopting dubious research for “things Celtic” is something of a pattern that I’ve traced in detail in The Chronicles of Prydain in my book.

“Succetus” is indeed recorded as one of St Patrick’s alternative names in Tírechán’s Collectanea (Account of St Patrick’s churches) from c. 670. The text itself translates what seems to be a British/Welsh name as “god of war” (see Dumville, 1993, p. 90). The somewhat fanciful translation of the name Patrick as “good cat” came from a book the name of which Alexander could no longer recall, but I’m now pretty sure it was Margaret Cooper Gay’s How to Live with a Cat (first published in 1946), in which she claims that St Patrick was originally “a Scottish monk named Su Cat” which may be translated as “Happy Warrior or the Good Cat” (Cooper Gay, 1969, p. 17). This example of Alexander repeating or adopting dubious research for “things Celtic” is something of a pattern that I’ve traced in detail in The Chronicles of Prydain in my book.

Cat in kimono in modern Japan (click image for source and more pictures)

The Irish episode in Time Cat brings together St Patrick and his mission, the folk belief of Ireland overridden with snakes until St Patrick banishes them (there’s an excellent scene of Gareth fighting a snake), and an element of romance between Jason and Diahan. Diahan is actually very much a prototype for Eilonwy. She is feisty, strong-minded, has “red-gold hair tossed about her soldiers” (p. 49) and chastises Jason for being impolite, or talks to him only to tell him that she won’t talk to him – all staples of Eilonwy-Taran interactions in the Prydain books.

Next stop: Japan 998 A.D. during the reign of Emperor Ichigo, when cats were introduced to Japan from China. Gareth and Jason teach the boy-Emperor Ichigo not only that cats aren’t toys to be played with and admired (and that it’s definitely NOT appropriate to dress his kittens in tiny embroidered kimonos!) but also how to find his voice and strength and assert himself over his rather nasty uncle-regent.

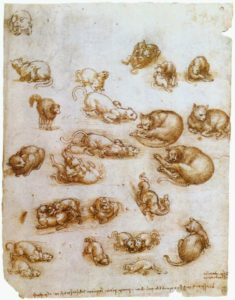

The fifth life Gareth and Jason visit is that of another historical figure, but this is perhaps the best-known one in the book: Italy 1468 and a young Leonardo da Vinchi, who is yet to convince his father that he doesn’t want to be a notary (as per the family tradition) but an artist. And, of course, Gareth and Jason end up becoming the catalyst for this! Leonardo, who writes his name backwards on his bedroom room (Odranoel), ends up creating a painting of a hybrid cat creature so life-like, that his father sees at last his talent. The inspiration is Gareth’s magnificent movements and feline physique. While Leonard works on drafting his painting, we literally see him producing the famous “Study sheet with cats” (Figure …), now in the Royal Collections:

Leonardo da Vinci, “Study sheet with cats, dragon and other animals” (click image to see larger version)

The boy picked up a bit of charcoal and began sketching rapidly on the back of an old sheet of paper. “The thing about cats,” Leonardo said, working along until the paper was covered, “is the way they’re made. Those muscles in the back legs. Can you imagine how strong they must be? That’s why cats can jump so high. And the back, it can move almost any way, like a sword blade.

“Everything is in balance,” Leonardo went on, “all the muscles and bones and joints. That’s what I want in the painting, too.”

“Well, I hope you aren’t going to paint bones and muscles,” Jason said. “I don’t think anybody would like that.”

“Of course I’m not going to paint just bones and muscles,” Leonardo said. “But I know where they are, even if nobody else sees them. And that’s bound to make the picture better.” (p. 112)

Next, Gareth and Jason move to 16th-century Peru (1555) and meet Diego Fernández, the man who soon after became the historian of Peru for the Viceroy (who ruled in the name of the King of Spain). Don Diego’s kind nature (clearly expressed via his fondness for cats) leads to an effort towards mutual understanding between the Incas and the Spanish conquistadors (I don’t know much at all about this era, but I wouldn’t be surprised at all if the story is a rather romanticised…)

Gareth and Jason next find themselves on the Isle of Mann in 1588, where they witness a cat (called Dulcinea) and her kittens arrive by sea in a barrel, having escaped a shipwreck. And, guess what? The cat is tailless, and therefore the originator of the famous Manx cats to come (so another aetiological story). Alexander is clearly here going with one of the popular beliefs about Manx cats: that they came from one of the ships of the Spanish Armada that sunk off the coast of the Isle of Man in 1588 (on exactly the date he chooses). There is no evidence for this and Manx cats, I understand, are now believed to be the product of a natural mutation that happened on the island (perhaps because of inbreeding). But the idea of the strange cat breed coming over the sea has its narrative uses, as Dulcinea, the kittens, Gareth, and Jason, now stick together and explore the island. The human story in this episode is about a young girl who thinks herself ugly because of her unusual eyes (one blue, one brown, like those of some cats, actually) who learns to appreciate that: “Beauty is inside, not on the face… If a person thinks he’s ugly, why then he begins to act in an ugly, cruel way” (pp. 152-3). Dulcinea and her kittens stay in the Isle of Man and become ship-cats, while Gareth and Jason move on to their next adventure.

This next episode is set in Germany in 1600, where things start feeling darker. Gareth and Jason find themselves in the midst of the witch-hunts of Early Modern Europe, when cats were equally persecuted as witches’ familiars, or demonic creatures. They manage to save an innocent woman who is falsely accused for witchcraft, but the end of this story doesn’t feel as neat and comfortable as previous ones. It looks like Jason is gradually coming to terms with more difficult moral questions, with Gareth as a wise guide.

This next episode is set in Germany in 1600, where things start feeling darker. Gareth and Jason find themselves in the midst of the witch-hunts of Early Modern Europe, when cats were equally persecuted as witches’ familiars, or demonic creatures. They manage to save an innocent woman who is falsely accused for witchcraft, but the end of this story doesn’t feel as neat and comfortable as previous ones. It looks like Jason is gradually coming to terms with more difficult moral questions, with Gareth as a wise guide.

And this emphasis on growing up and learning about things that may be more complex and less black-and-white continues in last episode, set in America in 1775, just as the American War of Independence is about to break out. Gareth and Jason meet a peddler-cum-teacher-cum-inventor who travels around Massachusetts selling “nature’s finest mousetraps”, i.e. kittens, while at the same time passes on messages to and from the Sons of Liberty and facilitates the forthcoming War of Independence. As Professor Parker aptly says: “countries are like cats. They like to settle down in their own ways. But they want their freedom, too. They’ll fight for it if they have to.” (p. 193).

The ending of this story is, again, a melancholy one, and the book then ends very quickly after that, with Jason back in his own home in the 20th century (I guess they’re in the USA anyway so this is only a travel in time, not time and place at the same time) and Gareth giving a rather didactic speech about everything Jason has learned in their time-traveling journey: how to grow up. (That’s the sort of thing modern children’s literature takes great pains to avoid announcing, but it remains a perennial theme, perhaps for inevitable reasons).

The novel includes some brilliant observations of cat appearance and behaviour – see, for example, the lovely opening of the novel:

Gareth was a black cat with orange eyes. Sometimes, when he hunched his shoulders and put down his ears, he looked like an owl. When he stretched, he looked like a trickle of oil or a pair of black silk pajamas. When he sat on a window ledge, his eyes half-shut and his tail curled around him, he looked like a secret. (p. 1)

There are numerous such scenes, like the demonstration of Gareth’s hunting “moves” in the Rome/Britain episode (again, beautifully observed and really well-rendered), and various moments of Gareth expressing affection by purring, and rubbing his head and tail against ankles.

There are numerous such scenes, like the demonstration of Gareth’s hunting “moves” in the Rome/Britain episode (again, beautifully observed and really well-rendered), and various moments of Gareth expressing affection by purring, and rubbing his head and tail against ankles.

There are also a number of “proverbial” phrases of feline nature, most of the time pronounced by Gareth, but also by Jason who really does know his cat! For example:

(Jason:) “A cat can belong to you, but you can’t own him. There’s a difference.” (p. 20)

(Gareth:) “I enjoy a comfortable bed… but if there isn’t one around, it doesn’t matter. Any bed is soft to a cat.” (p. 28)

(Gareth:) “The only thing a cat worries about is what’s happening right now. As we tell the kittens, you can only wash one paw at a time.” (p. 125)

(Gareth:) “It takes patience. But that’s one thing cats have a lot of. Why, even a kitten knows if you wait long enough someone’s bound to open the door.” (p. 184)