Dimitra Fimi's Blog, page 2

June 2, 2021

Surprises and Discoveries in the Drawings by Tolkien exhibition catalogue (1976)

I have been going through a number of small pamphlets and booklets in my Tolkien collection recently, and have been posting about them on Twitter:

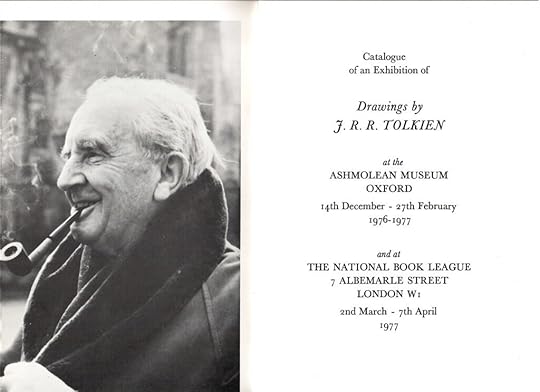

see here for a thread on the UK and USA Hobbit 50th Anniversart commemorative bookletsand here for for the sale catalogue of Pauline Baynes’s drawings and sketches at Blackwell’s Rare Books in 2015 (which also includes Narnia material) I started another thread today, on another booklet, and then realized I would have to eliminate interesting details to make it fit. So here’s my fuller discussion of Drawings by Tolkien, the catalogue of an exhibition of drawings by J.R.R. Tolkien at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 14th December-27th February, 1976-1977, and at the National Book League, 7 Albemarle Street, London W1, 2nd March-7th April, 1977.

I started another thread today, on another booklet, and then realized I would have to eliminate interesting details to make it fit. So here’s my fuller discussion of Drawings by Tolkien, the catalogue of an exhibition of drawings by J.R.R. Tolkien at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 14th December-27th February, 1976-1977, and at the National Book League, 7 Albemarle Street, London W1, 2nd March-7th April, 1977.

My understanding is that this was the first bespoke exhibition of Tolkien’s art, and marked the first publication of The Father Christmas Letters, ed. by Baillie Tolkien (1976), later revised and enlarged as Letters from Father Christmas (1999). Drawings from these letters were displayed as part of this exhibition.

The exhibition catalogue booklet opens with a “Foreword” by Kenneth John Garlick (1916-2009), Art historian and Keeper of Western Art at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, from 1968 until 1984. He remarks that “few can be aware that [Tolkien] was a practicing draughtsman, and water-colourist” and calls this “an unfamiliar and unexpected side to Professor Tolkien’s creative mind” (not that unfamiliar nowadays, of course!) He also notes that the selection of the exhibition items and the compilation of the catalogue entries was done by the Countess of Caithness (1954-1994), who apparently worked as a volunteer at the Ashmolean at the time, and Mr Ian Lowe (1935 – 2012), at the time the Assistant Keeper of Western Art at the Ashmolean, aided by Christopher Tolkien. Apparently, the Countess and Mr Lowe also had sight of the – then – unpublished manuscript of Humphrey Carpenter’s biography of J.R.R. Tolkien, which, the Foreword remarks, “is hoped will be published in the spring of 1977” (J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography was, indeed, published on 5 May 1977). Gratitude is expressed to both Christopher Tolkien and Humphrey Carpenter, but, Kenneth Garlick adds, both the Countess and Mr Lowe “recognize… that they are tyros in the field of Tolkien studies”. I am wondering, is this the first time the term “Tolkien studies”, as a field of academic research, was ever used?

The Foreword is followed by a short, but really fascinating, “Introduction” by Baillie Tolkien. In it she describes Tolkien’s art as “the product of a wholly private activity, ancillary to his writing” which was most likely never intended for publication or exhibition. She comments on Tolkien’s self-awareness of his limitations as an artist: for example he was perfectly aware that he wasn’t very good at drawing figures but she also argues that his drawings of Hobbits (sic) allowed other artists and illustrators to draw “extraordinary conclusions about their appearance”.

Baillie Tolkien also comments on Tolkien’s power to “render scenes visible with words alone”, which she describes as one of the great strengths of his writing, and goes on to protest that “is it all the more baffling that outrageously unapt pictorial material has often been published in connection with his books”, citing Tolkien’s own words upon seeing “an illustration by someone who had obviously not read the books”: “I sometimes think I am living in a madhouse’.

One wonders whether this type of comment refer to cases such as the infamous cover of the Ballantine edition of The Hobbit (showing a lion? and emus? really?) or other covers Tolkien had commented unfavourably on, such as the cover of the Swedish translation of The Lord of the Rings (1959).

Baillie Tolkien also makes some particularly apt remarks about Tolkien’s perception of beauty in his writings, as opposed to the colour palette in his art. She comments:

while beauty, in his writing, is almost always idealized, in terms of gold, or silver, or the bright glow of light from within (as exemplified most of all in the Silmarils), his painting nevertheless shows an exuberant use of bright and exotic colours, producing at times the effect of stained-glass windows, or the illuminations of medieval manuscripts.

She also singles out his artistry when drawing trees, a recurrent presence in his art, to which he manages to give “grace and character and individuality”.

Most importantly for what we now know came many many years after she wrote this Introduction, Baillie Tolkien notes that Tolkien’s drawings show “a deceptive combination of naturalism and formality”: naturalistic elements such as trees, rivers, etc. are brought together with “exotic” patterns, “not unlike tapestry”. One wonders whether the seeds of an idea were there already, not realized until many years later in the magnificent tapestries of Tolkien’s art at Aubusson.

Baillie Tolkien ends with a very discerning remark: reminding the reader that Tolkien may have disliked allegory, but insisting that he was “fascinated by symbols”. She argues that, from the beginning of his creative practice, Tolkien “explored the interrelationships of words, pictures, and symbols, inventing motifs, emblems, alphabets and scripts”, claiming that this is “the thread that connects everything he produced”. There is a lot to ponder about in this point, which links with the idea of naturalism and formality in Tolkien’s art (see above).

Baillie Tolkien’s Introduction is then followed by a brief “Biographical Note” by Humphrey Carpenter, a valiant attempt to summarise key points of his Tolkien biography, which was all but finished at that point, but not published yet. The only thing that made me stop and wonder in this “Biographical Note”, was this point by Carpenter:

This huge story [i.e. The Lord of the Rings], [is] truly a sequel to The Silmarillion rather than to The Hobbit.

In a way, I can see why Carpenter would say this: The Lord of the Rings isn’t a children’s book, with its more traditional “asides” and its simplification of the Middle-earth world (on which a lot of ink has been spilt!), but at the same time, this claim doesn’t quite work in terms of narrative threads (though, I guess, The Lord of the Rings does contain a summary of The Hobbit in its Prologue – I know I first read The Lord of the Rings without having read The Hobbit and had no problems following the plot). Still thinking about this, so leaving it here.

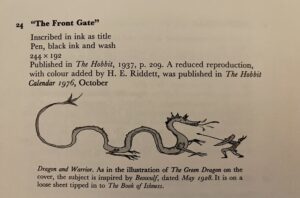

The catalogues booklet then moves to a traditional catalogue, explaining that the exhibition is arranged, “like Caesar’s Gaul” (!), into three parts: containing drawings associated with The Hobbit, The Father Christmas Letters, and The Lord of the Rings, respectively. There are no reproductions of images, bar a couple of monochrome details/scenes (see, for example, the “Dragon and Warrior” drawing below), but the catalogue describes the Hobbit illustrations as “bright and jewel-like”, singling out “Conversations with Smaug”.

The catalogue part on The Lord of the Rings makes an interesting comment on item 82, “Mt Doom”, later reproduced multiple times as “Barad-dûr: The Fortress of Sauron” (see relevant entry in Erik Mueller-Harder’s Tolkien Art Index: https://tai.tolkienists.org/tai/26/):

(82) is drawn on the back of a notice of a meeting of the Governors of the Schools of King Edward the Sixth in Birmingham dated 25 January 1939. Among the Governors was Professor L.P. Gamgee while the drawing shows Sam Gamgee’s path up Mount Doom.

Is the implication here that the name link prompted Tolkien to use this particular piece of paper to start this particular drawing? Another point to think about further.

The exhibition booklet, though on the surface pretty utilitarian, and not spectacularly illustrated like later catalogues of Tolkien exhibitions, was full of little surprises and discoveries for me – I’ve had fun exploring it in more detail and it’s given me a lot to think about further.

Endnote

According to the obituary of Diana Caithness (née Diana Caroline Coke): “Soon after her marriage to Malcy Caithness in 1975, she worked as a volunteer in the Ashmolean Museum, dealing with the drawings by JRR Tolkien which had been placed on deposit by his son Christopher and the family’s trustees. The drawings, which were subsequently transferred to the Bodleian Library, had never been seen in public before. To Diana Caithness’s lot fell the work of ordering and listing the very extensive collection, preparing the formal receipt, and then organising the first exhibition (together with the catalogue), which was held in the Ashmolean from December 1976 until February 1977. It was a great success. The Father Christmas Letters, written to Tolkien’s children, were then published for the first time.” Diana Caithness took her own life in 1994.

October 26, 2020

The Raw and the Cooked: William Morris’s Dwarf in The Wood Beyond the World, and J.R.R. Tolkien’s Gollum

This is a blog post I’ve been meaning to write for a few years now – in fact, every time I teach William Morris’s The Wood Beyond the World I tell myself I’ll get on with it, but every year I just allow myself to move on to other things. This time, however, I promised my students (this year’s cohort of our Masters in fantasy, the Fantasy MLitt at the University of Glasgow) that I would actually get my act together and write it – so there!

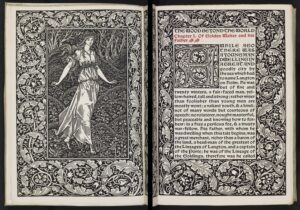

William Morris is often considered one of the “grandfathers” of modern fantasy, in the sense that Tolkien is (nearly) universally recognized as the father, and Tolkien (and Lewis, and many other later fantasists) read Morris and his writing shows clear echoes of Morris’s imaginative creations and narrative structures. Years ago, when I first read The Wood Beyond the World I was struck by a particular scene which chimed so closely with a very well-known scene in The Lord of the Rings, that I was stopped in my tracks.

The Wood Beyond the World (one of Morris’s romances, but clearly also a proto-fantasy) recounts the story of Golden Walter, a young man who is attracted to sail away by the vision of a strange trio: a hideous Dwarf, a fair Maiden, and an alluring Lady. He eventually finds himself in a remote land, an otherworldy place, where he will have to go through trials and tribulations to escape the (sexual) nets of the Lady (and her evil ally, the Dwarf) to free the captive Maiden (or, rather, to be saved by her, as the Maiden manages to save Walter and herself!) and find fulfilment and happiness. The scene that I found so striking occurs in Chapter IX, the first time Walter encounters the wicked Dwarf in the flesh, not just in vision.

The Wood Beyond the World (one of Morris’s romances, but clearly also a proto-fantasy) recounts the story of Golden Walter, a young man who is attracted to sail away by the vision of a strange trio: a hideous Dwarf, a fair Maiden, and an alluring Lady. He eventually finds himself in a remote land, an otherworldy place, where he will have to go through trials and tribulations to escape the (sexual) nets of the Lady (and her evil ally, the Dwarf) to free the captive Maiden (or, rather, to be saved by her, as the Maiden manages to save Walter and herself!) and find fulfilment and happiness. The scene that I found so striking occurs in Chapter IX, the first time Walter encounters the wicked Dwarf in the flesh, not just in vision.

First, Walter hears what he thinks is the voice of a beast – he hears “a strange noise of roaring and braying, not very great, but exceeding fierce and terrible, and not like to the voice of any beast that he knew”. His knees give way, he exclaims loudly, and tumbles down in a swoon when he sees the dwarf’s “hideous hairy countenance”. When he comes to his senses again, this scene follows (I am highlighting in red certain phrases I found significant):

How long he lay there as one dead, he knew not, but when he woke again there was the dwarf sitting on his hams close by him. And when he lifted up his head, the dwarf sent out that fearful harsh voice again; but this time Walter could make out words therein, and knew that the creature spoke and said:

“How now! What art thou? Whence comest? What wantest?”

Walter sat up and said: “I am a man; I hight Golden Walter; I come from Langton; I want victual.”

Said the dwarf, writhing his face grievously, and laughing forsooth: “I know it all: I asked thee to see what wise thou wouldst lie. I was sent forth to look for thee; and I have brought thee loathsome bread with me, such as ye aliens must needs eat: take it!”

Therewith he drew a loaf from a satchel which he bore, and thrust it towards Walter, who took it somewhat doubtfully for all his hunger.

The dwarf yelled at him: “Art thou dainty, alien? Wouldst thou have flesh? Well, give me thy bow and an arrow or two, since thou art lazy-sick, and I will get thee a coney or a hare, or a quail maybe. Ah, I forgot; thou art dainty, and wilt not eat flesh as I do, blood and all together, but must needs half burn it in the fire, or mar it with hot water; as they say my Lady does: or as the Wretch, the Thing does; I know that, for I have seen It eating.”

“Nay,” said Walter, “this sufficeth;” and he fell to eating the bread, which was sweet between his teeth. Then when he had eaten a while, for hunger compelled him, he said to the dwarf: “But what meanest thou by the Wretch and the Thing? And what Lady is thy Lady?”

The creature let out another wordless roar as of furious anger; and then the words came: “It hath a face white and red, like to thine; and hands white as thine, yea, but whiter; and the like it is underneath its raiment, only whiter still: for I have seen It—yes, I have seen It; ah yes and yes and yes.”

And therewith his words ran into gibber and yelling, and he rolled about and smote at the grass: but in a while he grew quiet again and sat still, and then fell to laughing horribly again…

Now, if you know The Lord of the Rings well, this scene cannot fail but bring to mind the famous scene with Sam and Gollum in Book IV, Chapter 4, “Of Herbs and Stewed Rabbit”. After Gollum brings in rabbits for Frodo and Sam to eat, and sees Sam starting a fire, he goes into an anxious frenzy, telling Sam to put off the fire as it will attract enemies. But Sam has firm plans and isn’t going to change them. He responds:

‘…I’m going to risk it, anyhow. I’m going to stew these coneys.’

‘Stew the rabbits!’ squealed Gollum in dismay. ‘Spoil beautiful meat Sméagol saved for you, poor hungry Sméagol! What for? What for, silly hobbit? They are young, they are tender, they are nice. Eat them, eat them!’ He clawed at the nearest rabbit, already skinned and lying by the fire.

‘Now, now!’ said Sam. ‘Each to his own fashion. Our bread chokes you, and raw coney chokes me. If you give me a coney, the coney’s mine, see, to cook, if I have a mind. And I have. You needn’t watch me. Go and catch another and eat it as you fancy – somewhere private and out o’ my sight. Then you won’t see the fire, and I shan’t see you, and we’ll both be the happier. I’ll see the fire don’t smoke, if that’s any comfort to you.’

Gollum withdrew grumbling, and crawled into the fern. Sam busied himself with his pans.

Later on, when Sam asks him to fetch herbs and mentions “taters”, Gollum asks him:

‘…What’s taters, precious, eh, what’s taters?’

‘Po – ta – toes,’ said Sam. ‘The Gaffer’s delight, and rare good ballast for an empty belly. But you won’t find any, so you needn’t look. But be good Sméagol and fetch me the herbs, and I’ll think better of you. What’s more, if you turn over a new leaf, and keep it turned, I’ll cook you some taters one of these days. I will: fried fish and chips served by S. Gamgee. You couldn’t say no to that.’

‘Yes, yes we could. Spoiling nice fish, scorching it. Give me fish now, and keep nassty chips!’

‘Oh you’re hopeless,’ said Sam. ‘Go to sleep!’

The two scenes present a series of remarkable parallels:

Both the hideous Dwarf in The Wood Beyond the World and Gollum make harsh and squealing noises and gesticulate – not just as a reaction to Walter’s or Sam’s words respectively, but as part of their more general behaviour patterns.

They both find the cooking of animal flesh as needless at best, and wasteful and wrong at worst: the Dwarf mockingly refers to Walter “half-burning” or “marring” coneys, or other meat because he is too “dainty”, while Gollum accuses Sam of “spoiling” or “scorching” the rabbits or fish and wasting good “tender” and “nice” raw meat. Clearly both the Dwarf and Gollum are more than content with raw flesh (a general sign of “primitiveness”, of “barbarians” or “savage” people from antiquity to Victorian perceptions – I shall return to this point below).

The Dwarf gives Walter what he calls “loathsome bread” which he clearly can’t abide, while Walter finds it “sweet between his teeth”; and Sam reminds Gollum that “our bread chokes you” – and that, of course, refers to the Elvish bread, lembas, as we have already seen Gollum choking on it earlier on, in Chapter 2, “The Passage to the Marshes”.

Notice also the use of the word “coney” which both Morris and Tolkien use instead of rabbit. Coney is a slightly more unusual/archaic word which fits well with Morris’s pseudo-romance language in works such as The Wood Beyond the World. Tolkien had already used “coney-rabbits” in one of his early poems (see one of my previous articles for where the rabbit imagery in that poem may come from) and in The Lord of the Rings contrasts Sam’s language, who uses “coneys”, with Gollum’s language, who uses “rabbits”.

One could just observe the parallels between those scenes as one of those cases when Tolkien is (perhaps unconsciously) recalling an incident he read in the past out of “the leaf-mould of the mind” (as Tolkien called all that an author has previously “seen or thought or read, that has long ago been forgotten, descending into the deeps”, quoted in Carpenter, 1977, 126). But I think that these resonances are not just a simple case of “borrowing”, or reproducing/adapting, an episode. They also overlap in terms of more structural elements in the two texts.

As briefly mentioned above, I think the binary of civilization vs. “savagery” or “barbarianism” (and I put these words in quotation marks because such labels really depend on whose perspective the story is told from) is a wider concern in both texts. In The Wood Beyond the World, the Dwarf has often been discussed as a representation of “the primitive, demonic forces in the world” (e.g. Silver, 1982, p. 167) showing signs of what the Victorians would have perceived as “savage”. He is initially described in very derogatory terms: “dark-brown of hue and hideous, with long arms and ears exceeding great and dog-teeth that stuck out like the fangs of a wild beast” (Chapter 2). Aside from assigning a bestial aspect to the Dwarf, this passage also identifies him as dark-skinned, and one cannot help but recall Victorian racial categorizations and prejudices, combining non-European physique with savagery, often also specifically associated with eating raw meat. The barbarians who eat raw meat are definitely a motif familiar from a long time earlier (e.g. from Classical writers such as Pomponius Mela, who wrote that the Germans ate the flesh raw, and with their hands), but we also see them in Victorian scientific papers and in novels such as Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Sign of the Four (1890) in which Tonga is displayed as “the black cannibal. He would eat raw meat and dance his war-dance”. This idea of culture vs. nature (in which civilization is positively inflected, and nature equates a more “primitive” stage of humanity) has also been discussed in the Gollum and Sam scene above by Thomas Honegger, drawing on Claude Lévi-Strauss’s well-known work The Raw and the Cooked (1964), the first volume from his Mythologiques (Honegger, 2013). Though Honegger highlights more strongly the difference in moral nature between Gollum (originally of hobbit-kind, but showing traces of moral and spiritual decline) and Sam (the hobbit par-excellence), he also recognizes Sam’s cooking gear as a sign of civilization, and – by extension – Gollum can also be discussed in terms of “primitiveness”.

As briefly mentioned above, I think the binary of civilization vs. “savagery” or “barbarianism” (and I put these words in quotation marks because such labels really depend on whose perspective the story is told from) is a wider concern in both texts. In The Wood Beyond the World, the Dwarf has often been discussed as a representation of “the primitive, demonic forces in the world” (e.g. Silver, 1982, p. 167) showing signs of what the Victorians would have perceived as “savage”. He is initially described in very derogatory terms: “dark-brown of hue and hideous, with long arms and ears exceeding great and dog-teeth that stuck out like the fangs of a wild beast” (Chapter 2). Aside from assigning a bestial aspect to the Dwarf, this passage also identifies him as dark-skinned, and one cannot help but recall Victorian racial categorizations and prejudices, combining non-European physique with savagery, often also specifically associated with eating raw meat. The barbarians who eat raw meat are definitely a motif familiar from a long time earlier (e.g. from Classical writers such as Pomponius Mela, who wrote that the Germans ate the flesh raw, and with their hands), but we also see them in Victorian scientific papers and in novels such as Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Sign of the Four (1890) in which Tonga is displayed as “the black cannibal. He would eat raw meat and dance his war-dance”. This idea of culture vs. nature (in which civilization is positively inflected, and nature equates a more “primitive” stage of humanity) has also been discussed in the Gollum and Sam scene above by Thomas Honegger, drawing on Claude Lévi-Strauss’s well-known work The Raw and the Cooked (1964), the first volume from his Mythologiques (Honegger, 2013). Though Honegger highlights more strongly the difference in moral nature between Gollum (originally of hobbit-kind, but showing traces of moral and spiritual decline) and Sam (the hobbit par-excellence), he also recognizes Sam’s cooking gear as a sign of civilization, and – by extension – Gollum can also be discussed in terms of “primitiveness”.

Another important point I’d like to make is that both the Dwarf in The Wood Beyond the World, and Gollum in The Lord of the Rings, have been read as the darker aspect of the two novels’ respective heroes. Both Andrew Dodds (1987) and Hilary Newman (2001) have discussed the Dwarf as symbolic of sexual rapaciousness without emotional attachment (something Morris would disapprove of), which makes him a perfect ally to the Lady, and a negative role-model for Walter. Newman has actually described the Dwarf “both as part of Waiter’s unconscious, and a physical presence” (2001, p. 51). Taking this one step further, the Dwarf represents Walter’s baser instincts, or Walter “gone wrong”. Similarly, Douglass Parker designated Gollum as Frodo’s “corrupted counterpart” (1957, 605), Thomson as “his double in darkness” (1967, 52), and Flieger described Gollum as Frodo’s “dark side, the embodiment of his growing, overpowering desire for the Ring” (2004, 143). Both the Dwarf and Gollum, therefore, occupy the position of the binary opposite to the main hero, but are also uncannily similar to him too.

As I said in the beginning, I’ve been meaning to write up this blog post for years, but as I finished, I thought, seriously, someone else must have spotted this particular scene in Morris as a Tolkien inspiration in all this time it took me to write this up! Well, fair is as fair does, so I did search for this and found two brief mentions, both dated 2014:

This anonymous post on “Thinklings: The Tolkien Ideas Group” blog, in which the two extracts are briefly compared but not explored further (I liked another parallel picked up here: “We also thought about how Gollum refers to Shelob enigmatically as ‘She’ and ‘Her’ and compared this to the enigmatic ‘Lady’ and ‘Thing’.”)

Gerard Hynes’s essay “From Nauglath to Durin’s Folk: The Hobbit and Tolkien’s Dwarves”, published in The Hobbit and Tolkien’s Mythology: Essays on Revisions and Influences , edited by Bradford Lee Eden (McFarland, 2014), in which the Dwarf’s preference for raw food is briefly compared to Gollum’s (p. 26), though The Wood Beyond the World is mostly used to show the ambiguity of the Dwarf figure in literature prior to Tolkien.

I am still rather surprised that this link hasn’t been explored further hitherto. This blog post is just opening up the conversation. I’d like to see more on Tolkien and Morris, not just source-spotting, but scholarship that will explore further the ideological echoes of Morris’s work and world in Tolkien’s legendarium.

References

Carpenter, Humphrey. 1977. J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography. London: George Allen & Unwin.

Dodds, Andrew. 1987. ‘A Structural Approach to The Wood Beyond the World’, Journal of William Morris Studies, 7.2: 26-28

Flieger, Verlyn. 2004. ‘Frodo and Aragorn: The Concept of the Hero’, in Understanding The Lord of the Rings: The Best of Tolkien Criticism, ed. by Rose A. Zimbardo and Neil D. Isaacs (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin), pp. 122-145.

Honegger, Thomas. 2013. “‘Raw Forest’ versus ‘Cooked City: Lévi-Strauss in Middle-earth”, in J.R.R. Tolkien: The Forest and the City, ed. by Helen Conrad-O’Briain and Gerard Hynes (Dublin: Four Courts Press), pp. 76-86

Newman, Hilary. 2001. ‘The Influence of De La Motte Fouqué’s Sintram and His Companions on William Morris’s The Wood Beyond the World’, Journal of William Morris Studies, 14.2: 47-53

Parker, Douglass. 1957. “Hwaet We Holbytla…”, The Hudson Review , 9.4: 598-609

Silver, Carole. 1982. The Romance of William Morris. Athens [Ohio]: Ohio University Press

Thomson, George H. 1967. “The Lord of the Rings: The Novel as Traditional Romance”, Wisconsin Studies in Contemporary Literature, 8.1: 43-59

October 1, 2020

Faërie: A Sonnet

It’s been a heady few weeks in my academic world. We recently launched the Centre for Fantasy and the Fantastic at the University of Glasgow (which I co-direct), I welcomed a new cohort of Fantasy MLitt students and started teaching the fantasy honours option, I delivered a keynote lecture for Oxonmoot 2020, and I recorded other video lectures on a number of topics for my students. And in the midst of this we’re still in the claws of a global pandemic, and everything feels hopeless and yet hopeful. So, because I did a lecture on the sonnet form this week, and because I encouraged my students to write a sonnet as the best way to understand the form, and because I must practice what I preach, and because, heck, it’s National Poetry Day today, here’s a sonnet, saturated with what my world (academic and not) feels like right now.

Faërie

The “once upon a time” of fairy-tales

Is not another time or other place,

It’s when the words and images set sails

In mind and heart to light our eyes and face.

We walk, we climb, we hurt, we make new trails,

In faërie stages do we set the pace,

Like merlins, ravens, owls, and nightingales,

We see the green sun rise in skies of grace.

No, Faërie-land is not another place.

Though like canaries we may start the rhyme,

Like phoenixes our feathers we replace,

And here and now we count the hours chime.

And while we’re here and fight with nail and tooth,

In Faërie we sojourn to find our truth.

Dimitra Fimi

1 October 2020

September 29, 2020

Epaminondas: Who was he, and why was Tolkien interested in him? (or, what’s different in the paperback edition of A Secret Vice?)

Since the publication of the paperback edition of A Secret Vice, I have been asked a few times what’s different or new, compared to the original hardback edition. My good friend and fellow Tolkien scholar Douglas A. Anderson actually asked me using the correct terminology: is the paperback a corrected reprint, or a revised edition? To be honest, this is a difficult question to answer. Most of the changes in the paperback text are just corrections of typos, or of words/word forms in Tolkien’s text we now know were misreadings. If those were the only changes, I would call the paperback a “corrected reprint”. However, there is one instance that murkies the water, and that’s the one I want to write about here.

Since the publication of the paperback edition of A Secret Vice, I have been asked a few times what’s different or new, compared to the original hardback edition. My good friend and fellow Tolkien scholar Douglas A. Anderson actually asked me using the correct terminology: is the paperback a corrected reprint, or a revised edition? To be honest, this is a difficult question to answer. Most of the changes in the paperback text are just corrections of typos, or of words/word forms in Tolkien’s text we now know were misreadings. If those were the only changes, I would call the paperback a “corrected reprint”. However, there is one instance that murkies the water, and that’s the one I want to write about here.

There is a word in the hardback edition of A Secret Vice that Andrew Higgins and I had marked as {illeg} (p. 98), our shorthand for a word that was impossible to make out from Tolkien’s hasty handwriting. The truth is that it wasn’t quite illegible. Both Andy and I had a pretty clear sense of what we thought the word was. But it just didn’t quite make sense – it was a seemingly random name. A proper name in Greek, belonging to a historical personality from the 4th century BC. There was no other reference of that name anywhere else in Tolkien’s written work or in his interviews and reported words by friends and colleagues, and we just couldn’t quite connect it securely to the context of the (actually fragment of a) sentence in Tolkien’s notes. So we reached the decision that we must have misread it, and could not quite make out the actual word Tolkien had intended. In all honesty, we marked it “illegible”.

Statue of Epaminondas in the grounds of Stowe House

The word we thought we could see was “Epaminondas” (Ἐπαμεινώνδας). Epaminondas (410-362 BC) was Greek general and statesman from Thebes. He was an important leader and military strategist: he effectively undermined the post-Peloponnesian-War military dominance of Sparta and changed the balance of power among Greek city-states. His most famous battle was that at Leuctra (371 BC), which was won partially due to his innovative military tactics. Our main sources for Epaminondas’ exploits is Xenophon’s Hellenica.

Epaminondas didn’t quite seem like the sort of historical personality that Tolkien would normally invoke, and his name didn’t seem to fit the context of the sentence we thought we saw it in. The sentence was:

What makes Greek sound Greek ({illeg}) (Secret Vice hardback, p. 98)

Here Tolkien is clearly in a note-taking mode, in preparation for (or in relation to) his brief “Essay on Phonetic Symbolism”. In that essay he writes about his interest in what constitutes the aesthetics of the sounds of a language – he characteristically asks:

Thus – what makes Greek so Greek? In what lies the Greekness of Greek, the Welshness of Welsh, the Englishness of English? (Secret Vice, p. 71)

Why would Tolkien invoke Epaminondas here when he was talking about Greek sounds? Could it be possible that he was particularly impressed by the sounds of this particular name? If that was the case, why hadn’t he mention it anywhere else before, especially in essays such as “English and Welsh”, in which he commented again on “the Greekness of Greek” (Monsters and the Critics, p. 191).

Well, it turns out he HAD mentioned this name again, but in a record that didn’t surface until a few months after our edition of A Secret Vice was published. Thanks to Stuart Lee’s archival work, we now know that during the filming of the BBC documentary Tolkien in Oxford (first broadcast in 1968), there were a lot of recorded scenes and conversations with Tolkien that were not used in the final documentary. Stuart found those hitherto lost film rushes. He revealed some of them in a BBC Radio 4 “Archive on 4” programme titled Tolkien: The Lost Recordings (first broadcast in August 2016) and he eventually published transcripts of Tolkien’s words in Tolkien Studies 2018. I was actually allowed to watch all of the lost Tolkien “rushes” for the BBC Radio 4 programme, for which I was interviewed, and so I heard Tolkien with my own ears talking about “the beginnings of inventing language” and how – alongside languages he knew as a boy, such as French and German – he came across the “totally different Greek taste”:

… which I first only knew by words like… ‘Epaminondas‘, ‘Leonidas’ and ‘Aristoteles’ and things of that kind. I tried to invent a language which would incorporate a feeling of that. (quoted in Lee, 2018, 136)

This was, for me, the “aha!” moment! Yes, Tolkien had mentioned Epaminondas before, together with other better-known names from classical Greek history and philosophy, and clearly this name did strike him as particularly aesthetically pleasing or striking in its sounds. (Notice also how he uses the proper Greek sound for Aristotle: Aristoteles – Ἀριστοτέλης!) But of course I had been shown the film rushes confidentially, for the purposes of the radio programme, with the understanding that I would not share their contents with anyone else. And I didn’t. I stewed in my own juices for two years and didn’t even tell Andy about this solution to one of the Secret Vice puzzles that had been bugging both of us, until Stuart actually published the transcripts, and they were then available to all scholars to see. So when the opportunity for the paperback edition of A Secret Vice arose, Andy and I were overjoyed to be able to restore this word to Tolkien’s text – a word we thought we could see, but couldn’t be quite sure was right, but which we now knew was totally right, and cross-checked with Tolkien’s own words in another instance.

Is this addition of one word in p. 98 of the paperback (and an explanatory note to go with it in p. 114) enough to move this edition from a “corrected reprint” to a “revised edition”? You tell me!

May 27, 2020

Lloyd Alexander’s “eat and read” regime: food and fiction!

I have briefly mentioned before Lloyd Alexander’s “eat and read” programme, but in these times of coronavirus, much more home-bound due to lock-down and the self-isolation advice, I have found myself reading more during the day, and cooking more, and thinking of the “eat and read” regime in a completely different light! So here it is!

I have briefly mentioned before Lloyd Alexander’s “eat and read” programme, but in these times of coronavirus, much more home-bound due to lock-down and the self-isolation advice, I have found myself reading more during the day, and cooking more, and thinking of the “eat and read” regime in a completely different light! So here it is!

Lloyd Alexander started reading when he was very young and his experience of getting lost in a book was intense and immersive. In an interview to James S. Jacobs, he claimed that one of his earliest “true” memories from childhood was his discovery that he could intensify the reading experience by combining it with a meaningful food:

The only rule was to find something to eat which was representative of the story which had currently captured him. Thus, when he read of King Arthur and the brown ale which foamed from his knight’s flagons, Lloyd must be partaking of the same drink (unfortunately he had to compromise with ginger ale, but that seemed close enough). While reading of Jim’s eavesdropping on Long John Silver from the bottom of an apple barrel, Alexander must be munching on the same crisp fruit. (Jacobs, 1978, p. 33)

Apparently. as Lloyd Alexander got older, his gastronomic needs while reading became somewhat more demanding: during elementary school he enlisted his mother in an effort to locate and taste the bloaters (type of whole cold-smoked herring) consumed in Dickens’s The Old Curiosity Shop (chapter 50). His mother accomplished this feat, but Alexander soon found out that bloaters “did not turn out to be what he had expected and his sympathies went out to the English” (Jacobs, 1978, p. 34)! In the event, he did not finish his dish of bloaters, but he did have the experience of eating them while reading the relevant scene, and that was the important thing!

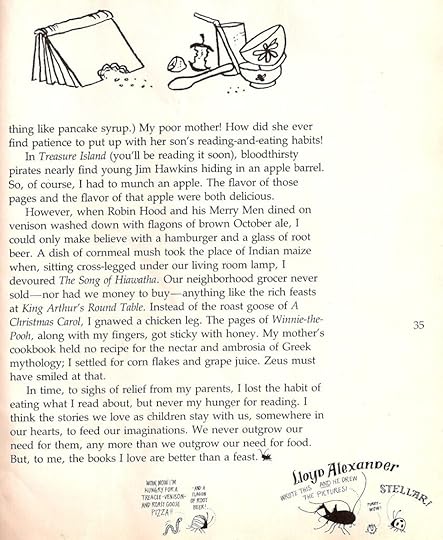

The “eat and read” regime persisted throughout Lloyd Alexander’s life. As a young man, working in a bank, he procured canned rattlesnake meat to munch upon while reading Kenneth Roberts’s Northwest Passage (Ibid., p. 114) and in 1973 he published a piece in the children’s magazine Cricket titled “A Hungry Reader” in which he described his childhood desire to have “a real taste of whatever food the people in the stories were eating” (p. 34). In that piece, reproduced below, he gave examples of other books that excited his tasting buds, including Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (tea, bread and butter, and treacle), The Song of Hiawatha (maize – he had to make do with cornmeal mush), A Christmas Carol (roast goose – a chicken leg had to do), Winnie-the-Pooh (honey!), and the stories of Robin Hood and his Merry Men (though he had to substitute “brown October ale” with root beer).

The “eat and read” regime persisted throughout Lloyd Alexander’s life. As a young man, working in a bank, he procured canned rattlesnake meat to munch upon while reading Kenneth Roberts’s Northwest Passage (Ibid., p. 114) and in 1973 he published a piece in the children’s magazine Cricket titled “A Hungry Reader” in which he described his childhood desire to have “a real taste of whatever food the people in the stories were eating” (p. 34). In that piece, reproduced below, he gave examples of other books that excited his tasting buds, including Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (tea, bread and butter, and treacle), The Song of Hiawatha (maize – he had to make do with cornmeal mush), A Christmas Carol (roast goose – a chicken leg had to do), Winnie-the-Pooh (honey!), and the stories of Robin Hood and his Merry Men (though he had to substitute “brown October ale” with root beer).

So, I am wondering, what food have you always thought about eating (or have actually munched!) while reading a particular book and found it very appropriate? I often crave apples when I read Little Women (which is no surprise – Jo is always munching one!), and – for some reason – seed cake when I read The Hobbit! Any other “eat and read” regime devotees out there?

“A Hungry Reader,” Cricket, I, January, 1973.

“A Hungry Reader,” Cricket, I, January, 1973.

References

Alexander, Lloyd. 1973. “A Hungry Reader”, Cricket, 1: 34-5

Jacobs, James S. 1978. Lloyd Alexander: A Critical Biography (EdD dissertation, University of Georgia)

May 18, 2020

Top 3 Fantasy Authors excluding Tolkien? Data from a Twitter snap poll.

A couple of weeks ago, I posted a tweet which ended up developing into a snap poll with over 450 responses. The question? Here it goes:

Please help me with a quick experiment to inform a discussion with our #Fantasy PhD students tomorrow: if I asked you to name the 3 best Fantasy authors of all time EXCLUDING #Tolkien, who would you list?@TolkienSociety @FanLit @UofGFantasy @FantasyArtStudi @BritFantasySoc pic.twitter.com/mXNAV8Gju7

— Dr Dimitra Fimi (@Dr_Dimitra_Fimi) May 4, 2020

As most of you know, I am Lecturer in Fantasy and Children’s Literature at the University of Glasgow, where I work alongside three other colleagues who research and teach on fantasy: Dr Rob Maslen, Dr Matt Sangster, and Dr Rhys Williams. At Glasgow we also have the world’s only Masters in Fantasy, and an amazing community of approximately 30 PhD students working on various aspects of fantasy literature and culture. In normal times, we meet our PhD students as a group once a month (over lunch), to discuss work in progress, go through a forthcoming paper, share and discuss a piece of scholarship, etc. As soon as the COVID19 crisis forced the University into lockdown, we moved these meetings online and made them more frequent (once every two weeks) to maintain as much as possible a sense of community in a time of isolation.

In these online meetings we often assign a particular essay/journal article/book extract to discuss. A few weeks ago, the assigned reading was Patrick Moran’s recent The Canons of Fantasy (Cambridge University Press). I had all sorts of issues with this book (no space or time to discuss those now) but one particular extract just struck me as particularly provocative:

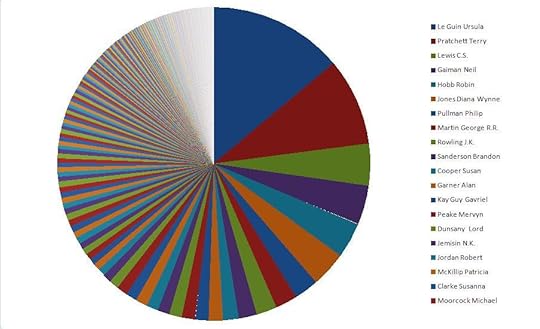

The canon of fantasy has a Tolkien-shaped problem. In the eyes of the general public, the Oxford don embodies the genre; he is often the only fantasy author that people know. The popularity of Peter Jackson’s films has only heightened this hegemony: no other adaptation of a fantasy work has reached such a wide audience. Of course, fantasy fans can name dozens of other authors who feel as important to them as Tolkien, maybe more so, be it Ursula K. Le Guin, Robert E. Howard, T. H. White, Michael Moorcock, George R. R. Martin, Guy Gavriel Kay, Robin Hobb, Tolkien’s friend C. S. Lewis and many others. But ask three fantasy fans who is the greatest fantasy writer besides Tolkien, and chances are they will give three different names. (p. 25)

Now, this sounded like a challenge to me. I will leave aside the question of whether Tolkien would actually top all the polls currently on who is the best(-known) fantasy author (again, that’s a discussion for another day and post). What really didn’t quite ring true for me was the suggestion that no clear “top” fantasy authors (apart from Tolkien) would naturally arise. My first instinctual response was that – whomever I could imagine I may have asked – Ursula K. Le Guin would come at the top. I was just absolutely certain about that, and willing to put my neck out.

This hopefully explains my Twitter question above, especially the request for three authors and no more (and I know this made it very hard for some people). What I think I had hoped for was perhaps 40-50 responses, and my hypothesis was that at least a couple of fantasy authors would come top at a good distance from others, disproving the statement above (and I was definitely expecting Le Guin to be the top one). So I just released my question to the Twittersphere, and – as per above – I just ended up doing nothing for about 24 hours other than recording and counting (and double-counting!) the responses I got (yes, 450 is a lot more than 50!)!!! And here are the results:

Poll results alert! Just over 450 respondents. Question: pick your 3 best #fantasy authors of all time EXCLUDING J.R.R. #Tolkien. 222 authors listed. Pie chart below, names of top 20 on the right. See THREAD for breakdown of votes for top 20!@UofGFantasy @FanLit @TolkienSociety https://t.co/tbyMl85Bt5 pic.twitter.com/TKyIoZKlsp

— Dr Dimitra Fimi (@Dr_Dimitra_Fimi) May 5, 2020

So, let’s have a look at the pie chart (which also includes the top 20 fantasy authors respondents voted for) more closely:

As you will see, we most definitely have two clear winners: Ursula K. Le Guin, with 171 votes, and Terry Pratchett with 111 votes. So main hypothesis vindicated (hooray!) but also a clear picture of not only a top 1 spot, but 2 top spots. After that, we have 4 authors in the 3rd spot territory, with votes around the 45-50 mark: C.S. Lewis (53), Neil Gaiman (50), Robin Hobb (45) and Diana Wynne Jones (also 45). The 4th spot is taken by 4 authors in the 25-30 votes range: Philip Pullman (31), George R.R. Martin (28), J.K. Rowling (26), and Brandon Sanderson (23). And that completes the top 10.

The next 10 spots are taken by authors who attracted roughly 15-20 votes: Susan Cooper (20), Alan Garner (18), Guy Gavriel Kay (17), Mervyn Peake (17), Lord Dunsany (16), N.K. Jemisin (15), Robert Jordan (15) Patricia McKillip (15), Susanna (14) and Michael Moorcock (14).

I am also giving below a table with the top 30 fantasy authors as voted by my respondents (actually 33, as there were many ties):

1

Ursula

Le Guin

171

2

Terry

Pratchett

111

3

C.S.

Lewis

53

4

Neil

Gaiman

50

5

Robin

Hobb

45

6

Diana Wynne

Jones

45

7

Philip

Pullman

31

8

George R.R.

Martin

28

9

J.K.

Rowling

26

10

Brandon

Sanderson

23

11

Susan

Cooper

20

12

Alan

Garner

18

13

Guy Gavriel

Kay

17

14

Mervyn

Peake

17

15

Lord

Dunsany

16

16

N.K.

Jemisin

15

17

Robert

Jordan

15

18

Patricia

McKillip

15

19

Susanna

Clarke

14

20

Michael

Moorcock

14

21

R.E.

Feist

12

22

Madeleine

L’Engle

11

23

Gene

Wolfe

10

24

David

Eddings

8

25

Michael

Ende

8

26

Robert E.

Howard

8

27

Fritz

Leiber

8

28

Ann

McCaffrey

8

29

Naomi

Novik

8

30

Patrick

Rothfuss

8

31

T.H.

White

8

32

David

Gemmell

8

33

Tamora

Pierce

8

Now, a few caveats: this was a snap poll and not a properly-designed academic survey. I have no data on the demographics of my respondents (I could, perhaps, work out locations from Twitter handles, though this isn’t always reliable, but I can say nothing about age, gender, etc.) At the same time, there was a strong self-selection bias: the Tweet was posted on my personal profile and was naturally first seen by my followers, and also by the followers of the accounts I tagged (@TolkienSociety, @FanLit, @UofGFantasy, @FantasyArtStudi and @BritFantasySoc). The original post was re-tweeted a lot (Twitter Analytics said that it has 54,527 impressions and 3,366 total engagements) but still, the Twittersphere is a limited pool with its own demographic preferences.

Still, I think the results I got from this small sample were really interesting and at least worth thinking about. A few points that seem important to me:

Ursula K. Le Guin emerged as the undisputed winner with over 50 votes difference from the next author. Terry Pratchett was also a clear runner-up, with over 50 votes difference from the next group of authors. This seems to at least somewhat contradict the argument that after Tolkien we’d have a big number of authors scoring roughly equally. I am wondering how the results would differ if Tolkien was not excluded, but, again, that’s a question for another day (for what it’s worth, I think that Le Guin and Pratchett would still be 2nd and 3rd respectively, with a clear difference).

There is well-balanced mix between writers of fantasy for adults and children’s fantasy writers. Fantasy is a broad church in this regard, and the differentiation between books for adults and books for children isn’t as sharp as in other genres.

I was really pleased to see one of the earliest fantasy authors make it to the top 20: Lord Dunsany was very influential in his time and clearly remains so!

The list is dominated by UK- and USA-based authors. I think this is more a result of the demographics of my respondents (my feeling – and it’s only a feeling, mind you – is that most people who responded lived in the UK or the USA). Fantasy writers not writing in English who were nominated included: Michael Ende (actually made it to the top 30), Astrid Lindgren, Italo Calvino, Cornelia Funke, Jorge Luis Borges, and Antoine de Saint-Exupéry.

The vast majority of respondents interpreted fantasy as modern fantasy, i.e. did not consider the authors of what Clute and Grant have called “taproot texts”. Still a few of those were also nominated, including: Homer, Aristophanes, the anonymous authors of Beowulf and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, and Shakespeare.

Last but not least, it was wonderful to see some important fantasy authors, artists, and editors, add their response to my snap poll. Here are a few responses that I think I, at least, would like to take note of:

Hope Mirrlees, Ursula Le Guin, Patricia McKillip.

— Terri Windling (@terriwindling) May 5, 2020

I knew it! Damn!

I’m going to go with living authors as an act of support & encouragement for all creative souls who fear they must be dead before they’ll matter. So I choose Frances Hardinge, Juliet Marillier & Naomi Novik!

— Kate Forsyth (@KateForsyth) May 4, 2020

Ursula Le Guin

Diana Wynne Jones

Susan Cooper

— Piers Torday (@PiersTorday) May 4, 2020

Leigh Bardugo @LBardugo

Nnedi Okorafor @Nnedi

Frances Hardinge @FrancesHardinge

— Sophie Anderson (@sophieinspace) May 4, 2020

April 1, 2020

Tolkien Reading Day 2020 – Interview with a Special Guest!

Exactly a week ago, it was Tolkien Reading Day 2020. Tolkien Reading Day is a worldwide celebration of J.R.R. Tolkien’s work, established by the Tolkien Society in 2003. It is held on the 25th of March, the date of the downfall of the Lord of the Rings (Sauron) and the fall of Barad-dûr.

Exactly a week ago, it was Tolkien Reading Day 2020. Tolkien Reading Day is a worldwide celebration of J.R.R. Tolkien’s work, established by the Tolkien Society in 2003. It is held on the 25th of March, the date of the downfall of the Lord of the Rings (Sauron) and the fall of Barad-dûr.

This year, the global COVID19 pandemic kept many Tolkien scholars and fans away from special events usually organized by local Tolkien societies and groups on Tolkien Reading Day, but fortunately Jeremy Edmonds of https://www.tolkienguide.com (@TolkienGuide) stepped in and organized an amazing live-streamed programme of readings by Tolkien scholars, artists, actors, and fans! I took part via a brief recording (life is too complicated just now for live appearances!) but I did have with me a very special guest!!! If you missed it, here’s your chance to listen again!

January 3, 2020

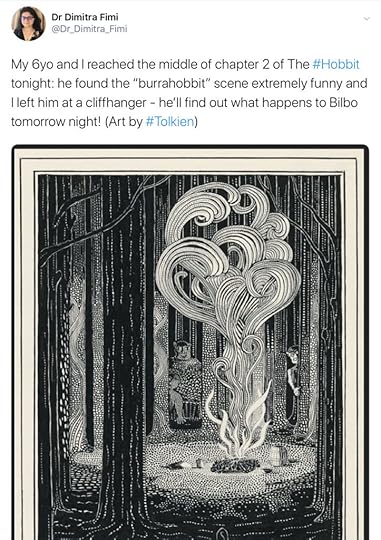

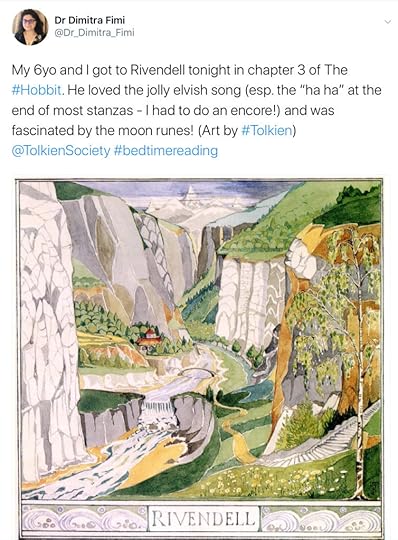

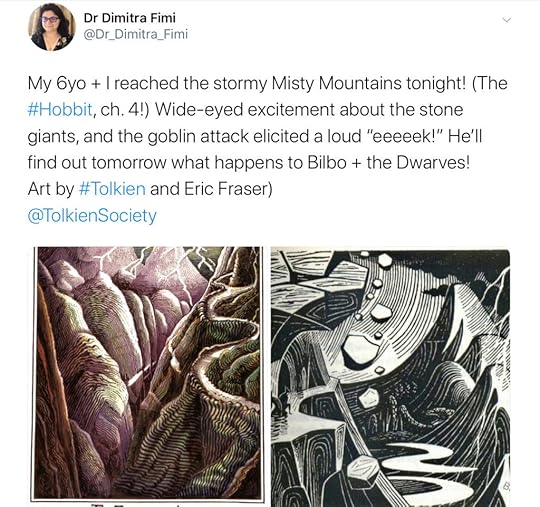

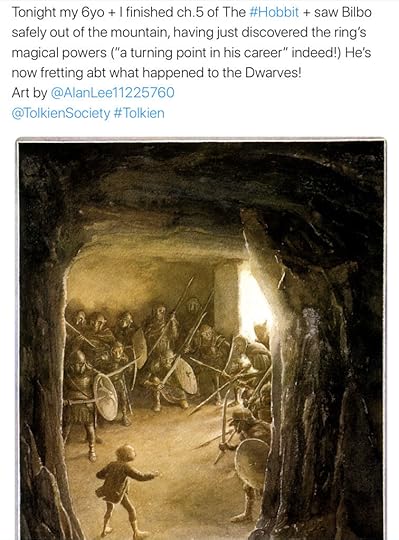

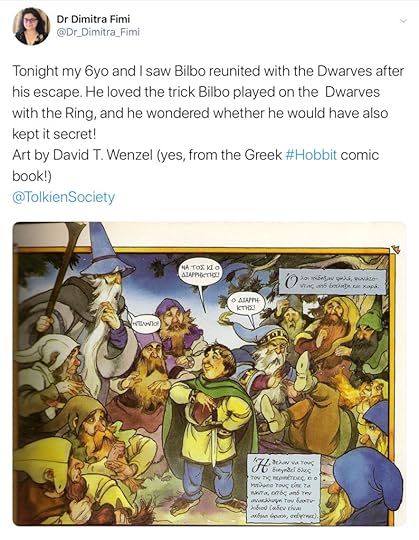

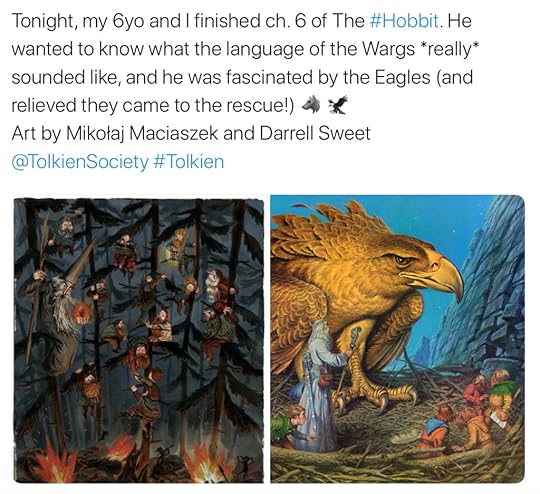

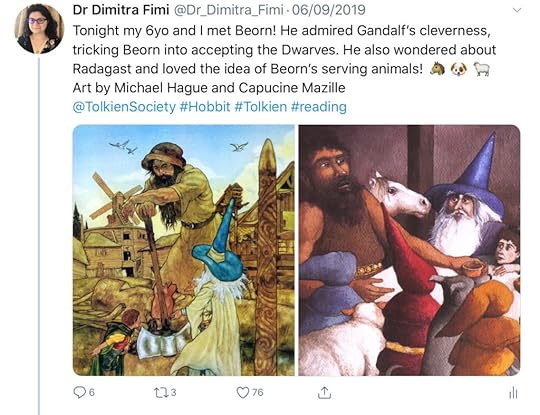

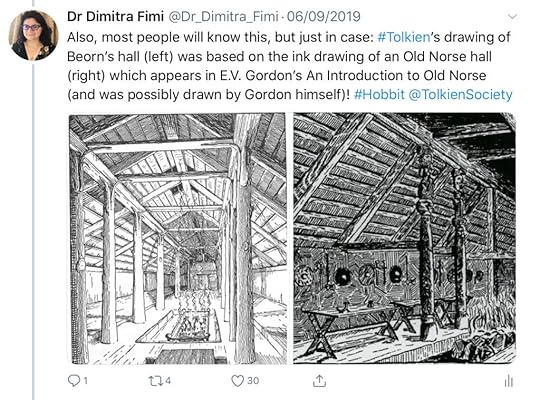

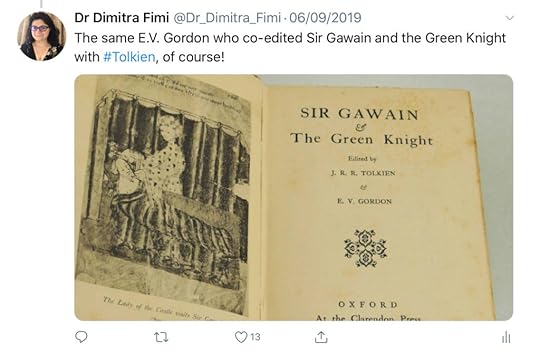

Reading J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit with my 6-and-a-half-year-old son: a journal

One of the highlights of 2019 was reading J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit aloud to my 6-and-a-half-year-old son at bedtime. We started towards the end of August 2019, and finished it in just over a month. I tweeted the entire experience as we went, often commenting on points in the text that I hadn’t quite noticed before, and which reading to a young child brought to the forefront. Reading aloud really showcases the oral origins of The Hobbit, a story Tolkien told his children many times before writing it down and “fixing” the text (in the event, the text wasn’t really “fixed” until a major revision after The Lord of the Rings).

So here is my reading journal, exactly as it appeared on Twitter, warts and all (you will notice the glaring typo in the very first entry!!!). Each image links to the relevant tweet, in case you want to follow comments, etc.

So this was my Twitter journal of reading The Hobbit with my son. Here are two bonus tweets, one during the time we were still reading the story, and the other a few weeks later:

And here are a few more bonus images: my son’s Hobbit fan-art! Can you guess who is who?

December 15, 2019

A Homeric Simile in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings and Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials

I managed to watch episode 7 of BBC’s adaptation of His Dark Materials live tonight. It included a scene I’ve been looking forward to for weeks now. Like many others, I am sure, I re-read Pullman’s entire trilogy a couple of months ago, in preparation for the series, and I was reminded of something I had noticed the very first time I read Northern Lights, and had discussed with my students at the time, but had then promptly forgotten about. But this time it stuck, and that’s probably because it came in close proximity (timewise) with noticing the exact same phenomenon in a text I have read (and taught) goodness knows how many times, but failed to spot (at least consciously) before: Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. The phenomenon is a literary one, and a very ancient one too: a Homeric simile.

What is a Homeric simile? A good working definition is a simile that runs on for a few lines and creates an elaborate comparison (in contrast to the usual short formula of “x is like y”). The Homeric simile formula tends to be: “like/as” + first part of the comparison followed by “just so/thus/that’s how” + second part of the comparison. Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey are full of such long, elaborate similes (hence the term “Homeric”), and here is a typical example:

Just as a evil-minded lion comes upon cattle, that are grazing in countless numbers in the low land in a great marsh. Among them is a herdsman not yet experienced in fighting a wild beast over the carcass of a crooked-horned cow; but he walks with the herd, first in front and then behind—while the lion leaping into the middle devours a heifer, and all the rest flee. Just so were the Achaeans powerfully routed by Hector… (Iliad, 15.629–36)

Interestingly, just like in the Iliad, both in His Dark Materials, and in The Lord of the Rings, a Homeric simile occurs at the moment, or on the aftermath, of battle.

In His Dark Materials, we find it in Chapter 20 of Northern Lights, titled “Moral Combat”, when Iorek Byrnison and Iofur Raknison do battle, instigated by Lyra’s trickery. It is a crucial moment in the book, because “Iorek and Iofur were more than just two bears. There were two kinds of beardom opposed here, two futures, two destinies”. They first challenge each other with ritualistic words, and then it all kicks off with a Homeric simile just on cue:

Then with a roar and a blur of snow both bears moved at the same moment. Like two great masses of rock balanced on adjoining peaks and shaken loose by an earthquake, which bound down the mountainsides gathering speed, leaping over crevasses and knocking trees into splinters, until they crash into each other so hard that both are smashed to powder and flying chips of stone: that was how the two bears came together. (Northern Lights, Chapter 20: “Mortal Combat”)

In Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, the Homeric simile occurs just after the One Ring has been cast in the fires of Mount Doom, and outside the gates of Mordor, where the armies of Gondor are attempting to distract Sauron from Frodo’s quest, a “great wind” has just indicated that something has changed. This is another case of a crucial moment in a long narrative. As Gandalf says: “The realm of Sauron is ended! […] The Ring-bearer has fulfilled his Quest”. And then:

The Captains bowed their heads; and when they looked up again, behold! their enemies were flying and the power of Mordor was scattering like dust in the wind. As when death smites the swollen brooding thing that inhabits their crawling hill and holds them all in sway, ants will wander witless and purposeless and then feebly die, so the creatures of Sauron, orc or troll or beast spell-enslaved, ran hither and thither mindless; and some slew themselves, or cast themselves in pits, or fled wailing back to hide in holes and dark lightless places far from hope. (The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, Book VI, Chapter 4: “The Field of Cormallen”)

In both cases, the Homeric similes work to amplify the “epic” moments they refer to. As outlined in William C. Scott’s influential study they are both “long digressions”, and each one of them is “in motion” – they are stories that “have a beginning, a middle, and an end”. And they are not just decorative, but they “significant parts of each book’s theme” – the epic battle of different visions of existence in the former, and the mindlessness of evil in the latter. Also, in both of them the writer “creates a strong break from the locale of the ongoing narrative for digressions that develop their own stories in response to their own motivations” – although there’s something eminently comparable between armies of humanoid-beings and “armies” of ants; and giant polar bears’ doing battle and rocks clashing during an earthquake.

There are no other Homeric similes that I could find in the rest of His Dark Materials and The Lord of the Rings, but do let me know if you spot any I missed!

November 18, 2019

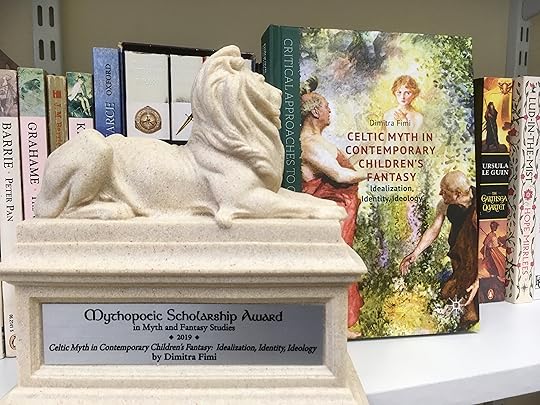

Celtic Myth in Contemporary Children’s Fantasy wins Mythopoeic Award!

I was absolutely thrilled to find out a couple of months ago that my recent monograph, Celtic Myth in Contemporary Children’s Fantasy, had won the Mythopoeic Scholarship Award in Myth and Fantasy Studies!

I was absolutely thrilled to find out a couple of months ago that my recent monograph, Celtic Myth in Contemporary Children’s Fantasy, had won the Mythopoeic Scholarship Award in Myth and Fantasy Studies!

This is my second Mythopoeic Award: my first monograph, Tolkien, Race, and Cultural History, had won in a different category: the Mythopoeic Scholarship Award for Inklings Studies for 2010.

This latest award is extra special, not only because my book was in a short-list of very strong contenders (Helen Young’s excellent Race and Popular Fantasy Literature: Habits of Whiteness among them), but also because previous winners in this category are books by brilliant scholars, which I have been using in my teaching and research for years, such as Brian Attebery’s Strategies of Fantasy, Marina Warner’s From the Beast to the Blonde, Carole Silver’s Strange and Secret Peoples, and Catherine Butler’s Four British Fantasists.

Today, my Aslan arrived (hooray!!!), and I have just seen that my acceptance remarks are now on the Mythopoeic Society website:

This book was long in the making, bridging my interests in Celtic studies and children’s fantasy. It brings together concepts and approaches from different fields: folklore, reception studies, fantasy literature, children’s literature, and Celtic studies, in order to explore what perceptions of the “Celtic” mythological past (often idealized and romanticized) some of the most successful contemporary fantasy texts for young readers evoke. During the period of research for this book I made some unexpected discoveries (e.g. the much more Gravesian vision of Prydain in the first draft of Lloyd Alexander’s The Book of Three), and I was very privileged to talk to many of the authors whose work I discussed in the book (special thank you to Jenny Nimmo, Catherine Fisher, Susan Cooper, and Henry Neff). I followed characters into Tír na nÓg, and I witnessed heroic, haunting, or funny semi-divine figures from Irish and Welsh legend walk in modern Britain or USA. I saw young protagonists saving the world (either our world, or a Celtic-inspired otherworld) or finding their identity and inner strength via communing with mythological figures from the “Celtic” past. The journey itself was worth it anyway, but this recognition from the Mythopoeic Society makes this book extra special! Many thanks! Diolch yn fawr! Go raibh maith agat!