Blake Charlton's Blog, page 4

July 18, 2011

Spellbound Book Tour

Dearly Beloved You Guys:

So, I'm nearly halfway through my pediatrics rotation and loving it. The kids are, as to be expected, unbelievably cute. More on that later. Possibly much later. Now I've very excited to announce Spellbound's book tour. This year it's looking like I'll be running up and down the left side of the country; however, Stanford has graciously given me some time away from the hospital, so if you know of a bookstore, book club, or school that would be especially keen on having me come talk or read, let me know and I might be able to make it somewhere near or at least closer to you.

Meanwhile, here's the schedule. I will be signing first editions US hardbacks at all the bookstores and most will be selling them online. Links provided. I'll be trying to put together small get together's before or after so that I an get a coffee/beer/sarsaparilla with anyone who wants to chat. Lemme know if you're keen!

Friday, September 16th, Launch party at Kepler's Books, Menlo Park, CA

Tuesday, September 20th, Powell's Books, Beaverton, OR

Wednesday, September 21st, U of W Bookstore, Seattle, WA Friday,

The Signed Page, Seattle, WA *Signed by me and cover artist Todd Lockwood

September 23rd, Mysterious Galaxy, San Diego, CA

In other news, I did the usual requesting, charming, begging to get ARCs into the hands into as many reviewers as possible. So if you asked for one, hopefully it's gotten there already or it's on the way.

July 5, 2011

New Foreign Cover Art

Dearly Beloved You Guys:

By the time you read this, my week on the well-baby nursery will be afoot. Let's hold the phone for a moment to think about well-babies. They're cute. They pee and poop with abandon, and their physical findings are strange. Consider heart sounds. In the adult, the healthy human heart produces a lub'dub… lub'dub… lub'dub consisting for four separate, synchronized sounds –it's like a barbershop quartet. I spent two years promoting Stanford's attempt to revitalize the physical exam, so I feel quite comfortable listening to adult heart sounds. In fact, I enjoy it. It's reassuring to hear a healthy heart, and an abnormal rhythm presents a diagnostic puzzle. In the neonate…well..all four sounds are there…and, one hopes, the rhythm is regular…however…well…the rate… You see, an adult heart rate shouldn't get much higher than 99 beats per minute. The neonate heart, however, will normally fly along at 170 beats per minute. In effect, the neonate heart is still like a barbershop quartet, but the quartet is anxious, and singing double time, and high on amphetamines.

In short, I feel completely unprepared to examine los personas muy pequeños. And yet…so it goes with medical training–read a lot; know a little; jump into the clinic; learn a bit more; repeat. So, if you have a second, wish me luck with the wee ones.

Anyway, let's get on with the post. A few bits of news.

Latest I've heard, the pub date for the UK edition of Spellbound has been pushed back to September 29th. Why? Something to do with publishing schedules beyond my or your or any one mortal's control. Oh, yeah, and there's some guy named GRRM who's got some kinda epic fantasy book, or something, that's supposed to be soaking up all the attention. Maybe you heard of this RR guy.

Also, the Spanish cover! Estoy muy satisfecho con el debut de la cobertura en español de "Spellbound". Me encanta el diseño icónico y colores vivos. Espero que los lectores en España y América Latina están de acuerdo. (Spanish speakers: if your feeling charitable, let me know how badly I screwed up the grammar there.)

Also, the Dutch cover art for Spellbound is out. What do I think of it? Well, you'll have to wait until I've learned enough Dutch to tell you, don't you? Why don't you tell me what you think of it.

June 27, 2011

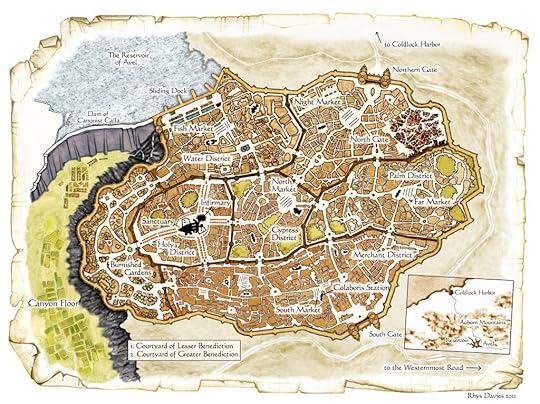

Spellbound's Beautiful City Map

Last year I was lucky enough to show of the world map for the Spellwright Trilogy. It was drawn by the brilliant Rhys Davies; if you're into imaginary maps, you really should click through.

Today, I'm very proud to show off a second Davies map. This one will run in Spellbound and provides detailed cartography of the City of Avel. Here's how I described the inspiration for Avel in an interview with Civilian Reader:

Avel is a bustling city in the deep savannah of the kingdom of Spires. Its structure and culture was inspired by the medieval cities of Morocco. When I was a teenager, I did a student travel program and I ended up spending a summer in the beautiful city of Meknes. Later when I traveled in Spain, I saw a lot of similar architectural and cultural elements. In particular, a similar use of cumin in both Moroccan and Spanish cooking struck me. Even the languages have many commonalities: for example, the Spanish word for rice "arroz" comes from the Andalusian Arabic word "aruzz." Even more intriguing to me was remembering that I had encountered many of these cultural and linguistic elements in the Americas. Mexican cuisine also incorporates cumin, and many of the grandest structures built by Spanish settlers have Moorish (i.e. Moroccan) elements. For example, last year I was lucky enough to travel to Peru. In Lima, I visited El Covento de San Francisco and was delighted at one point to find myself standing under an ornate and beautiful ceiling decorated with a "Moorish Star" pattern: the ceiling was almost an exact replica I had seen as a teenager in a very distant North African city. Anyway, my epic fantasy writer imagination had found a source of inspiration. I read up on Al Andalusia, the many different Catholic kingdoms of medieval Spain, the Ottoman Empire in Northern Africa. All of them got mashed up with a dash of pure fabrication to produce the architecture, politics, and culture of Spires. I had a lot of fun dreaming the place up, and I very much hope that readers have fun exploring Avel and the surrounding cities on an adventure.

Let me know what you think!

April 14, 2011

Hair-Raising Medical Bureaucracy

As with all other posts about medicine, the following has been altered to remove any identifying information.

**RING RING**

Blake: Hello.

Unnamed and Really Very Nice Hospital Administrator: Hello, is this Medical Student Blake Charlton?

Blake: Yes.

Admin: This is the hospital security department. We can't process your photo ID request because you left "hair color" blank.

Blake: That's because I don't have any.

Admin: Color?

Blake: Hair.

Admin: But what color is it?

Blake: No color.

Admin: So…white?

Blake: No! I mean yes. I mean I'm white, but my hair isn't because I don't have any.

Admin: Okay, sir, but what color would it be?

Blake: …

Admin: Sir?

Blake: Okay, guys ha ha. Who set this up?

Admin: What color was your hair?

Blake: Did Paolo Bacigalupi set this up like he did the WorldCon 2006 crank call?

Admin: Paul Bacigawhopi?

Blake: Or is this Morgan and Danica?

Admin: Oh! Sir, okay, can you tell me what color your eyebrows are?

Blake: Um…brown?

Admin: Thank you, Sir.

Blake: Wait, you really are—

**CLICK**

Hair-Raising Bureaucracy

As with all other posts about medicine, the following has been altered to remove any identifying information.

**RING RING**

Blake: Hello.

Unnamed and Really Very Nice Hospital Administrator: Hello, is this Medical Student Blake Charlton?

Blake: Yes.

Admin: This is the hospital security department. We can't process your photo ID request because you left "hair color" blank.

Blake: That's because I don't have any.

Admin: Color?

Blake: Hair.

Admin: But what color is it?

Blake: No color.

Admin: So…white?

Blake: No! I mean yes. I mean I'm white, but my hair isn't because I don't have any.

Admin: Okay, sir, but what color would it be?

Blake: …

Admin: Sir?

Blake: Okay, guys ha ha. Who set this up?

Admin: What color was your hair?

Blake: Did Paolo Bacigalupi set this up like he did the WorldCon 2006 crank call?

Admin: Paul Bacigawhopi?

Blake: Or is this Morgan and Danica?

Admin: Oh! Sir, okay, can you tell me what color your eyebrows are?

Blake: Um…brown?

Admin: Thank you, Sir.

Blake: Wait, you really are—

**CLICK**

March 30, 2011

Vote on the Gemmell Awards!

Dearly Beloved You People,

Polls have opened for the David Gemmell awards in fantasy literature. If you've got two second to make two clicks, please hope over to the Morningstar Award for best debut fantasy and pick your favorite. I'm hoping you'll vote for Spellwright but there are some amazing books on that list so go where your heart tells you. I'm honored and grateful just to be on the same list as all those fantastic authors! I very much admire what the Gemmell Award is doing for fantasy and think it's a great way for the reading community to interact; you can also vote for best fantasy and for best artwork.

In other news, I've finished up my psychiatry rotation and have a month to get back to writing. Presently, I'm cranking through the "proofs" of Spellbound and scheming for it's launch in August/September!

March 12, 2011

Spellbound's UK Cover

Gentle (or Otherwise) Readers,

This week I was very proud to see the cover for the UK edition of Spellbound debut over at The Speculative Scotsman. It's a wonderful blog for SFF reviews and witty commentary on matters literary and cultural. In fact, given that I'm still working away in the hospital this month, why don't we list TSS as the diversion site du jour.

Meanwhile, let's trot out the Spellbound UK cover.

February 28, 2011

Gone Head Shrinking (Diversion Post)

Dearly Beloved You Guys:

Today starts my rotation in psychiatry. As the son of two shrinks, this day has long been anticipated by clan Charlton. A strong desire to uphold the family honor and to "not suck" (that's a biomedical technical term) will likely keep me from much internet activity until April when I'm back to research and writing. Should you wonder how it's all going, feel free to check in on my personal twitter or fbook feeds. I plan to snark there in a totally non-HIPAA-violating way.

News wise, I'm happy to report the paperbacks of Spellwright are running loose in the British Isles and the German translations have landed on shelves in Deutschland.

But, should you feel that you need to get your SFF medical fix, I strongly recommend you visit Dr. Grasshopper over at How to Kill Your Imaginary Friends.

(P.S. Despite the suspicions of some and a few rather amusing emails attempting to "prove" otherwise, I am not Dr. Grasshopper. This is readily evident by the "Dr." in front of Grasshopper's name. I am merely a medical student. So, if you run across a blog run by a "Student Doctor Skitter" or "Pillbug MS3," you should maybe grow suspicious, but not until then. Furthermore, I have had the pleasure of meeting Grasshopper MD and can report that we are different human beings. )

February 21, 2011

Writing Strong Women

The following is a crosspost of my contribution to Mary Victoria's "Writing Strong Women" series.

Let me tell you the stories of three women.

Or, to be more precise, the stories of a dead woman, a living girl, an imaginary girl.

The dead woman's story—as I witnessed it—starts when she was alive.

It's my first year of medical school, and we're learning biochemistry, the molecular basis of disease and medication. Not. so. lively. Then, one day we're treated to an interview between Dr. Gilbert Chu, a famous oncologist, and a vivacious octogenarian, whom I'll name Helen (not her real name). In her late sixties, Helen was diagnosed with ovarian cancer and begun on chemotherapy. At a hospital outside of my academic center, her chemotherapy regimen was confused, and she was accidentally given a medication called Cisplatin. It's a platinum molecule turned biological weapon: it crossbinds DNA, crumpling up genes like a hand wadding up a sheet of newspaper. In very small doses, cisplatin is highly effective against certain types of cancer. Helen was supposed to receive a lot more of a milder drug, but she was given cisplatin at the dosage for a milder drug. Technically, Helen was given a 'massive overdose."

The horrors of routine chemotherapy are well-known: hair loss, nausea, vomiting, weight loss, etc. Cisplatin is notorious for sudden, violent side effects. So much so that oncology nurses sometimes refer to it as "cis-flatten'em." Helen's massive overdose pushed her beyond what was well known and into blindness, deafness, grand mal seizures, kidney failure. At this point, Helen was transferred to my hospital. Under the direction of Dr. Chu, a technological effort worthy of a medical TV drama was begun. Helen just barely survived, but she was rendered nearly deaf. Her vision was drastically decreased for more than a year, and she required a kidney transplant

And yet…and yet…her character suffered no damage. During the interview, it became apparent that she had a personality bigger than the whole hospital. She was cracking jokes with and about the famous oncologist. When she overheard a few of the female med students talking about the upcoming med student formal dance, she told a few of the male medical students in the front row (included me) that she was single. My class loved her. She was incandescent. That's just who she was. It wasn't surprising when we learned that one of the doctors caring for her (not Dr. Chu) fell in love with her; after her recovery, they were married and lived well until his death decades later.

It boggled my mind. Where was her anger at the medical establishment? Where was the bitterness I would have felt if I had been put through such an ordeal? When she answered questions from the audience, I asked exactly that. She grew serious and said something like, "I was angry and bitter. But when you're alone and in the dark, and you're blind and deaf, when you're trapped, you have to find a way to go on. You don't immediately realize there's a choice of how you go on. And somehow I went on in a way so that I could talk to you all, here, much later."

That ended Helen's lecture. I didn't suppose ever to see her again. A few weeks later, I encountered the story of the living girl.

I met Angela (not her real name) shortly after she lost her heart. And both her lungs. The surgeons cut down the center of her chest and took out all three of the concerned organs and replaced them with those of a donor. She had a very rare disease of unknown cause. She was 16 years old. I was assigned to her in a big sib / little sib program between medical students and children with chronic disease. This was our first meeting and she was only 5 days post op. No one yet knew if her body would reject the transplanted organs: a result that would put her in mortal danger. As I sat there, on the flimsy hospital chair, she looked me over and—in the tone unique to an exasperated young woman—said, "Well…this is awkward." A week later, she texted me "OMG, I'm holding my heart in my hands." I had been in histology lecture, but afterwards I stopped by her room. She was holding a dilated and plasticized bit of muscle. "Why the hell do they give us these things back?" she asked. And, really, I don't know why they gave her heart back to her. It's…odd. Anyway, Angela didn't reject her transplants. I would sit with her when she had to come into the hospital, or wait for an appointment in clinic. Sometimes she was bitter. She would wonder "why me?" Not an uncommon feeling for a 16 year old; even for those 16 year olds possessing all of their original internal organs. But Anglia is tough. Nowadays, she's doing well, going to college. Occasionally, she texts me during her more tedious lectures.

But before Angela got to college, there was the story of the imaginary girl.

Her name is Stephanie. That's her real name. To the extent that she's real. She's a teenage brain cancer patient who discovers she's in a hospital for the dead. Things get weirder and more science fictional as the story goes on. You can read it here. Or, if you're the listening type, you can hear it on an Escape Pod podcast. I wrote that story briefly after meeting Helen and Angela. In fact, Stephanie is the composite of Helen and Angela's characters jammed into a plot I dreamt up during a boring neuroscience lecture. I was also drawing upon my experiences from the year I spent with my father after his diagnosis of a very dangerous type of cancer. (Dad's, miraculously, fine now.) When I learned that story was going to be published in the Seeds of Change anthology I was thrilled. It was my first publication.

I asked Angela if she wanted a copy of the anthology. She didn't like sci-fi. And that's cool. But I was pretty sure Helen would like a book. Even if she didn't read the story; she'd like knowing she was part of the book. I kept meaning to ask our famous professor to make a book hand off to Helen. But one thing led to another. I was busy. Medical students usually are. I decided to wait until the next year; Helen would come in to give her lecture to the new class of first years. However, when I was taking a spring-quarter autopsy elective, the pathologists brought in Helen's body. She'd died suddenly; the pathologists were supposed to find out why. It felt like a kick in the gut, like I wanted to vomit or cry. I didn't do either. I turned away before they opened Helen up; I left the room. So far that has been the only sight in medical training I have turned away from.

And I'll never forget Helen's character.

And that brings me to my only contribution of advice for this wonderful series on writing strong women: Take note of extraordinary women, try to feel what about them moves you, combine aspects of different extraordinary women (if needed), and then run them through the labyrinth of your plot.

For writers, I don't think it's helpful to think about character. Female or male. Plot, sure, think about plot long and hard. Think about what your reader will think about the plot. The labyrinth, the puzzle, misdirect your reader so you're always one step ahead. Cat and mouse, cloak and dagger. It's like that.

But character is harder, in my opinion. No amount of thinking is going to get you there. You have to find the characters. Female or male. The protagonists of my first novel, Spellwright, are lifted from the characters—mostly boys—I witnessed when I was a learning disabled student in special ed. The protag of my second novel, Spellbound, is inspired by several female surgeons. (Coincidentally, surgeons are often interesting people. It's a male dominated field, so many of the women—especially those who broke into the field years ago—are especially interesting.)

But extraordinary patients and surgeons are just the crowd I fell in with. I've no doubt you find women just as extraordinary in a law firm, sandwich shop, or nuclear submarine. You just have to look for them.

So that's it. My only bit of advice. It's a simple idea really. If you want to write extraordinary women or men, don't think about them, go out and talk to them.

Writing Strong Women—Blake Charlton

The following is a crosspost of my contribution to Mary Victoria's "Writing Strong Women" series.

Let me tell you the stories of three women.

Or, to be more precise, the stories of a dead woman, a living girl, an imaginary girl.

The dead woman's story—as I witnessed it—starts when she was alive.

It's my first year of medical school, and we're learning biochemistry, the molecular basis of disease and medication. Not. so. lively. Then, one day we're treated to an interview between Dr. Gilbert Chu, a famous oncologist, and a vivacious octogenarian, whom I'll name Helen (not her real name). In her late sixties, Helen was diagnosed with ovarian cancer and begun on chemotherapy. At a hospital outside of my academic center, her chemotherapy regimen was confused, and she was accidentally given a medication called Cisplatin. It's a platinum molecule turned biological weapon: it crossbinds DNA, crumpling up genes like a hand wadding up a sheet of newspaper. In very small doses, cisplatin is highly effective against certain types of cancer. Helen was supposed to receive a lot more of a milder drug, but she was given cisplatin at the dosage for a milder drug. Technically, Helen was given a 'massive overdose."

The horrors of routine chemotherapy are well-known: hair loss, nausea, vomiting, weight loss, etc. Cisplatin is notorious for sudden, violent side effects. So much so that oncology nurses sometimes refer to it as "cis-flatten'em." Helen's massive overdose pushed her beyond what was well known and into blindness, deafness, grand mal seizures, kidney failure. At this point, Helen was transferred to my hospital. Under the direction of Dr. Chu, a technological effort worthy of a medical TV drama was begun. Helen just barely survived, but she was rendered nearly deaf. Her vision was drastically decreased for more than a year, and she required a kidney transplant

And yet…and yet…her character suffered no damage. During the interview, it became apparent that she had a personality bigger than the whole hospital. She was cracking jokes with and about the famous oncologist. When she overheard a few of the female med students talking about the upcoming med student formal dance, she told a few of the male medical students in the front row (included me) that she was single. My class loved her. She was incandescent. That's just who she was. It wasn't surprising when we learned that one of the doctors caring for her (not Dr. Chu) fell in love with her; after her recovery, they were married and lived well until his death decades later.

It boggled my mind. Where was her anger at the medical establishment? Where was the bitterness I would have felt if I had been put through such an ordeal? When she answered questions from the audience, I asked exactly that. She grew serious and said something like, "I was angry and bitter. But when you're alone and in the dark, and you're blind and deaf, when you're trapped, you have to find a way to go on. You don't immediately realize there's a choice of how you go on. And somehow I went on in a way so that I could talk to you all, here, much later."

That ended Helen's lecture. I didn't suppose ever to see her again. A few weeks later, I encountered the story of the living girl.

I met Angela (not her real name) shortly after she lost her heart. And both her lungs. The surgeons cut down the center of her chest and took out all three of the concerned organs and replaced them with those of a donor. She had a very rare disease of unknown cause. She was 16 years old. I was assigned to her in a big sib / little sib program between medical students and children with chronic disease. This was our first meeting and she was only 5 days post op. No one yet knew if her body would reject the transplanted organs: a result that would put her in mortal danger. As I sat there, on the flimsy hospital chair, she looked me over and—in the tone unique to an exasperated young woman—said, "Well…this is awkward." A week later, she texted me "OMG, I'm holding my heart in my hands." I had been in histology lecture, but afterwards I stopped by her room. She was holding a dilated and plasticized bit of muscle. "Why the hell do they give us these things back?" she asked. And, really, I don't know why they gave her heart back to her. It's…odd. Anyway, Angela didn't reject her transplants. I would sit with her when she had to come into the hospital, or wait for an appointment in clinic. Sometimes she was bitter. She would wonder "why me?" Not an uncommon feeling for a 16 year old; even for those 16 year olds possessing all of their original internal organs. But Anglia is tough. Nowadays, she's doing well, going to college. Occasionally, she texts me during her more tedious lectures.

But before Angela got to college, there was the story of the imaginary girl.

Her name is Stephanie. That's her real name. To the extent that she's real. She's a teenage brain cancer patient who discovers she's in a hospital for the dead. Things get weirder and more science fictional as the story goes on. You can read it here. Or, if you're the listening type, you can hear it on an Escape Pod podcast. I wrote that story briefly after meeting Helen and Angela. In fact, Stephanie is the composite of Helen and Angela's characters jammed into a plot I dreamt up during a boring neuroscience lecture. I was also drawing upon my experiences from the year I spent with my father after his diagnosis of a very dangerous type of cancer. (Dad's, miraculously, fine now.) When I learned that story was going to be published in the Seeds of Change anthology I was thrilled. It was my first publication.

I asked Angela if she wanted a copy of the anthology. She didn't like sci-fi. And that's cool. But I was pretty sure Helen would like a book. Even if she didn't read the story; she'd like knowing she was part of the book. I kept meaning to ask our famous professor to make a book hand off to Helen. But one thing led to another. I was busy. Medical students usually are. I decided to wait until the next year; Helen would come in to give her lecture to the new class of first years. However, when I was taking a spring-quarter autopsy elective, the pathologists brought in Helen's body. She'd died suddenly; the pathologists were supposed to find out why. It felt like a kick in the gut, like I wanted to vomit or cry. I didn't do either. I turned away before they opened Helen up; I left the room. So far that has been the only sight in medical training I have turned away from.

And I'll never forget Helen's character.

And that brings me to my only contribution of advice for this wonderful series on writing strong women: Take note of extraordinary women, try to feel what about them moves you, combine aspects of different extraordinary women (if needed), and then run them through the labyrinth of your plot.

For writers, I don't think it's helpful to think about character. Female or male. Plot, sure, think about plot long and hard. Think about what your reader will think about the plot. The labyrinth, the puzzle, misdirect your reader so you're always one step ahead. Cat and mouse, cloak and dagger. It's like that.

But character is harder, in my opinion. No amount of thinking is going to get you there. You have to find the characters. Female or male. The protagonists of my first novel, Spellwright, are lifted from the characters—mostly boys—I witnessed when I was a learning disabled student in special ed. The protag of my second novel, Spellbound, is inspired by several female surgeons. (Coincidentally, surgeons are often interesting people. It's a male dominated field, so many of the women—especially those who broke into the field years ago—are especially interesting.)

But extraordinary patients and surgeons are just the crowd I fell in with. I've no doubt you find women just as extraordinary in a law firm, sandwich shop, or nuclear submarine. You just have to look for them.

So that's it. My only bit of advice. It's a simple idea really. If you want to write extraordinary women or men, don't think about them, go out and talk to them.