Susan M. Weinschenk's Blog, page 30

February 19, 2016

Looking for a User Experience and/or UI Design Job?

I love connecting people and opportunities, and here’s a chance for one of those connections.

I love connecting people and opportunities, and here’s a chance for one of those connections.

I often get emails from people who are looking to build a career in user experience and/or UI Design. If that’s you, or if you know someone who is looking, then here’s some great news:

Our colleagues at Balanced Experience are looking for talented staff to place at Fortune 500 clients in the U.S. One position is posted so far at their site, but they will have more shortly, so if you are interested please see their careers page, and/or email them: info@balancedexperience.com

New college graduates (Bachelors or Masters) are especially encouraged to apply.

Tell them that The Brain Lady sent you!

February 11, 2016

The Next 100 Things You Need To Know About People: #109 — People Prefer Symmetry

Take any object—a photo of a face or a drawing of a circle or a seashell—and draw a line down the middle either horizontally or vertically. If the two halves on either side of the line are identical, then the object is symmetrical.

People rate symmetrical faces as more attractive. The theory is that this preference has to do with an evolutionary advantage of picking a mate with the best DNA.

Steven Gangestad (2010) at the University of New Mexico has researched symmetry and shown that both men and women rate people with more symmetrical features as more attractive. But symmetry isn’t only about faces: bodies can be more or less symmetrical, too.

So why do people find symmetry to be more attractive? Gangestad says it may have to do with “oxidative stress.” In utero, babies are exposed to free radicals that can cause DNA damage. This is called oxidative stress. The greater the oxidative stress there is, the greater the asymmetry in the face and/or body. From an evolutionary and unconscious viewpoint, people look for partners who have no DNA damage. Symmetrical features are a clue that someone has less DNA damage. As further proof, research shows that men who are rated more attractive have fewer oxidative stress chemicals in their blood.

So, when deciding what photos to use on your website, for example, choose pictures of people who are more symmetrical than less, since those people will be viewed as more attractive.

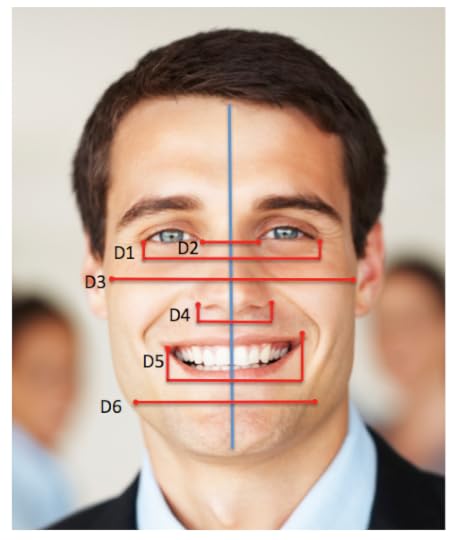

Measuring face symmetry — You can use a ruler to measure the symmetry of a face. Using the face at the top of this blog post as an example, you would:

Measure the distance from the left edge of D1 to the centerline.

Measure the distance from the right edge of D1 to the centerline. Write down the difference between the two lines. For example, if one side of D1 is .5 inch longer than the other side, write down .5.

Take the same measurement for D2, D3, D4, D5, and D6. It doesn’t matter which side is longer or shorter. All your difference numbers should be positive—no negative numbers.

Add up all the differences.

The higher the sum of the differences is, the more asymmetrical the face. If the sum of all the differences is 0, then the face is perfectly symmetrical. The further from zero the total is, the more asymmetrical the face.

Gender differences — Men prefer symmetry in bodies, faces, and just about everything else, including everyday items, abstract shapes, art, and nature. But research by Kathrine Shepherd and Moshe Bar (2011) showed that women prefer symmetry in faces and bodies, but not as much as men for everything else.

If you’re designing for a primarily male audience, then pay special attention to symmetry, whether it’s in faces, bodies, natural or man-made objects, or product pages with TVs—try to use symmetrical objects and show them in an equal right/left and top/bottom view. Men will find symmetrical images most appealing.

If you’re designing for a primarily female audience, then symmetry in faces and bodies of people is the most important. You don’t have to be as concerned with making sure all the products are symmetrically displayed.

Why do people prefer symmetry in objects? — There might be an evolutionary advantage for preferring symmetry in a mate, but why do people prefer symmetry in objects? Some researchers have proposed that the brain is predisposed to look for symmetry, and so people see symmetrical objects faster and make sense of them faster. The theory is that this visual fluency with symmetrical objects makes people feel as though they prefer the objects. They may just find them easier to see and understand. But why this is true for men and not for women remains a mystery.

What about symmetrical web page designs? — Does the research on symmetry mean that your design should always be perfectly symmetrical? If you design a symmetrical layout, then you know that people will perceive it quickly and will more likely prefer it—especially if your target audience is men. On the other hand, if you go with an asymmetrical layout, then people will most likely be surprised by it. That may grab their attention initially, but the advantage of surprise and initial attention getting may be offset by fewer people liking it.

Here’s the research:

Gangestad, Steven W., Leslie A. Merriman, and Melissa Emery Thompson. 2010. “Men’s Oxidative Stress, Fluctuating Asymmetry, and Physical Attractiveness.” Animal Behaviour 80(6), 1005–13. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2010.09.003.

Shepherd, Kathrine, and Moshe Bar. 2011. “Preference for Symmetry: Only on Mars?” Perception 40: 1254–56.

If you liked this article, and want more info like it, check out my newest book: 100 MORE Things Every Designer Needs To Know About People.

February 4, 2016

The Next 100 Things You Need To Know About People: #108 — Our 5 Senses Are Swappable

Over 285 million people are visually impaired in the world. What if they could see using their taste buds in the tongue rather than their eyes?

Over 285 million people are visually impaired in the world. What if they could see using their taste buds in the tongue rather than their eyes?

A woman who is blind puts on a pair of glasses that contain a camera. The image from the camera is sent to a small device about the size of a postage stamp that sits on her tongue. She feels a sensation like soda bubbles on her tongue—this is the camera signals being sent to electrodes on her tongue. This information then goes either to the visual cortex or to the part of the brain that processes taste signals from the tongue. The scientists who developed this technology say they aren’t sure which part of the brain is actually receiving the information from the tongue in this situation.

The taste buds are seeing — The experience of the woman when her brain receives the signals from her tongue is that she sees shapes. The vision is not the same as normal sight, but she can see enough that she can better navigate her environment. People who are totally blind can find doorways and elevator buttons when they use the device, called a BrainPort. They can read letters and numbers and pick up everyday objects, for example, a fork at the dinner table.

The brain is learning — When someone uses the BrainPort at first, they don’t see anything. It takes fifteen minutes for them to start to interpret the signals as visual information. Interestingly, it’s not that they have to “learn” anything —it’s not that they are conscious of practicing. The brain is unconsciously learning to interpret the information as vision.

Design to augment — According to the World Health Organization, over 39 million are blind and 246 million have moderate to severe visual impairment.Over 360 million have disabling hearing loss. Until now, designing devices for people with visual, auditory, or other physical impairments has been an area that a small number of designers have worked on. The rest of the designers have been told to make their designs “accessible” so that the special devices (such as screen readers) are compatible and can use the mainstream technologies. Keeping accessibility in mind is always important, but now more designers will be directly designing devices that are specifically created to augment the impaired sense.

What do you think? Will these devices become more common? If you are a designer would you like to work in this field?

January 26, 2016

The Next 100 Things You Need To Know About People: #107 — Laughter Helps Us Learn

Let’s say you decide to let your 18-month-old daughter play some learning games on your tablet. You have a couple of apps you’ve downloaded and you’re trying to decide which one to give to her: The one that introduces number and letter concepts with music but is pretty serious? Or the one that makes her laugh with the silly animals that keep popping up and running around the screen?

Let’s say you decide to let your 18-month-old daughter play some learning games on your tablet. You have a couple of apps you’ve downloaded and you’re trying to decide which one to give to her: The one that introduces number and letter concepts with music but is pretty serious? Or the one that makes her laugh with the silly animals that keep popping up and running around the screen?

Since you’re not sure that “screen time” is a good thing for young children, you choose the serious one. At least she’ll learn, you think.

Actually, the one that makes her laugh is the better decision.

Rana Esseily (2015) conducted research on babies as young 18 months old. There are many research studies that show that when children laugh, it enhances their attention, motivation, perception, memory, and learning. But this study was the first to try out the idea on children as young as 18 months old.

The children in the group who did a task in a way that made them laugh learned the target actions more than those in the control group who were not laughing during the learning period.Esseily hypothesizes that laughter may help with learning because dopamine released while laughing enhances learning. Other research points to the idea that it works on adults too!

Here’s the research:

Esseily, Rana, L. Rat-Fischer, E. Somogyi, K. O’Regan, and J. Fagard. 2015. “Humour production may enhance observational learning of a new tool-use action in 18-month-old infants.” Cognition and Emotion, 1-9 DOI: 10.1080/02699931.2015.1036840

If you liked this article, and want more info like it, check out my newest book: 100 MORE Things Every Designer Needs To Know About People.

January 22, 2016

The Next 100 Things You Need To Know About People: #106 — People Prefer Objects With Curves

Do people prefer logos with curves rather than logos with interesting angles? Have you noticed that your favorite smartphones, tablets, and laptops tend to have rounded corners?People prefer objects with curves—a preference that’s evident even in brain scans. This field of study is called neuroaesthetics.

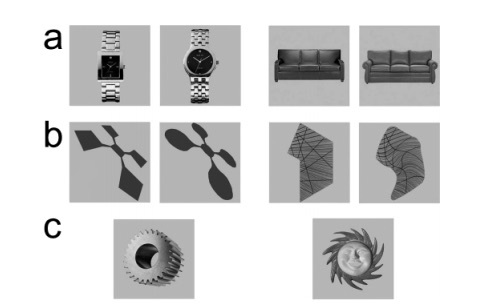

Bar and Neta showed concrete and abstract images with and without curves to people, for example, the images below:

Moshe diagram (http://barlab.mgh.harvard.edu/publica...)

People gave higher “liking” ratings to the objects with curves. Bar and Neta’s theory was that the sharp and angled images conveyed a sense of threat.

What about complex shapes? Silvia and Baron tested complex, angular shapes and complex shapes with slightly curved edges. Again, people preferred the objects with curves.

Helmut Leder Pablo Tinio and Bar (2011) asked whether this preference for curves was true for both “positive” objects (birthday cakes and teddy bears) and “negative”objects (razor blades and spiders). The results? People preferred curves in objects that were either positive or neutral, but there was no preference for curves in negative objects.

Curves stimulate the brain — Ed Connor and Neeraja Balachander took this idea into a neuroimaging lab. Not only did people prefer rounded shapes, there was more brain activity in the visual cortex when they viewed shapes that were more curved and more rounded.

Takeaways:

People prefer curves

If you’re creating a logo, incorporate some form of curve in the design

If you’re creating areas of color on a screen, consider using a “swoosh” or curved shape

If you’re designing actual products – such as smartphones, remote controls, medical devices, or other hand-held items – used curved surfaces.

Nike, Apple, Pepsi, Coca-Cola and dozens of other well-known brands use one or more curves in their logos. Did they fall into curves or did they do their homework?

Here are the research references:

Bar, Moshe, and Maital Neta. 2006. “Humans prefer curved visual objects.” Psychological Science. 17(8): 645-648.

Leder, Helmut, P.P.L. Tinio, and M. Bar. 2011. “Emotional valence modulates the preference for curved objects.” Perception. 40, 649-655.

If you liked this article, and want more info like it, check out my newest book: 100 MORE Things Every Designer Needs To Know About People.

January 11, 2016

Apply For A FREE Engagement Evaluation

Would you like to get FREE advice on how to create a more engaging product, website, or app? And help train the next generation of designers?

Would you like to get FREE advice on how to create a more engaging product, website, or app? And help train the next generation of designers?

I am once again teaching a semester course at the University of Wisconsin, Stevens Point, on “Design for Engagement” in the Web and Digital Media Development department. In the class we use “real life” case studies. A team of 3-4 students is assigned to a client. They perform an Engagement Audit and make suggestions for re-design.

If you have a project/product that you would like evaluated you can apply to be a team case study. If chosen you receive a free audit and you will be helping to train the next generation of designers.

What you should expect:

You will spend about 2-3 hours a month for February, March, April, and early May working with your team. This will be via email, Skype and/or teleconference. You will be speaking with them about your website, software, or app, your target audience and goals and giving them feedback on the Engagement Audit report that they prepare for you.

At the end of the semester you will have suggestions for how to re-design your product so it is more engaging, and you will have some example mock-ups. Please note that you should not expect an entire re-design of your product and you should not expect actual progamming/coding.

Here are the requirements:

You have an existing or prototyped website, software, or app, in English.

The team can access the product or prototype.

You have time to meet with the team remotely, answer their questions and give feedback in a timely manner.

Here’s what you need to submit in an email to: susan@theteamw.com

Your Name:

Your Contact Info:

Brief Description of the product/website/app etc:

Brief Description of your engagement challenges:

Instructions for how we can access the product:

Who the product is for — /users/visitors/intended audience:

What the users/visitors/intended audience want to do with the product:

What YOU want them to do with the product:

Anything else you think we should know:

Let me know if you have questions, and thanks in advance for submitting your product for a possible evaluation.

December 12, 2015

New Book Tour for 2016

Want to host a Brain Lady keynote and/or workshop?

I’ll be going on the road in 2016 for a book tour for my new book: 100 MORE Things Every Designer Needs To Know About People. We are looking for some sponsoring partners.

We’re flexible, but here are the basics — We are looking for companies and organizations that want to bring us in for a keynote or workshop internally, or who want to partner with us to host and help market a public keynote and/or workshop in select cities.

If you are interested, let us know: info@theteamw.com and we can talk details.

November 11, 2015

New Online Video Course: Be Your Own Boss

Starting when my son, Guthrie, was about 8 years old I would talk to him about my consulting, teaching, and speaking business. He’d help me strategize about products and services, pricing, marketing, and sales. He was a great sounding board, and I was surprised that someone so young was actually full of good ideas.

Little did I know at the time that after a degree in Economics, another in International Studies, and then a Law degree, after working for BP, and a logistics firm and a law firm, and coaching people on starting small businesses, that he would pitch to me to come onboard my business as a part-owner. But he did, and I said yes. Guthrie started full time on September 1 of this year as my Chief Operating Officer. And now we have a new online video course. that we are co-instructors on.

It’s different than the other courses I’ve done before, so it may not be appropriate for everyone who reads the blog. It’s called “Be Your Own Boss: Start and grow your own small business.” It’s all about how to turn your passion into a small business and how to make sure it is profitable. The course fee is $145, but we are offering the course through November at a special price of $9.

Here is the coupon code: https://www.udemy.com/beyourownboss/?couponCode=SmartBus

which will take you to the course on Udemy.com

In the course I handle the psychology/behavioral science/how to decide what you want to do part, as well as marketing and sales. Guthrie handles practical topics such as pricing, profitability, business management, and legal issues.

The course has over 5 hours of video, with quizzes throughout and exercises that you can send to us for feedback.

So if you, or someone you know, wants to turn their passion into profit, or has a small business and wants it to really take off, check out the course. You can start by watching some of the free preview videos.

Let me know if you have questions!

Susan

November 2, 2015

The Next 100 Things You Need To Know About People: #105 — Video Games Increase Perceptual Learning

When my son was about 6 years old, we were shopping one day in a large department store when we walked by a section of demo video games. A group of 10-to 13-year-olds were intensely playing the games and my son was fascinated. I was one of “those parents” who didn’t allow any video games in the house. My son stopped to watch. Not wanting him to get too interested, and also being in a rush to get my shopping done, I said something like, “You don’t want to play video games. See, it’s scrambling their brains.” It’s one of the many nonsensical things that seemed to just come out of my mouth as a busy and distracted parent.

I started walking to the checkout lanes and then realized that my son hadn’t budged. But instead of staring intensely at a video game being played he was now staring at one of the boys playing the video games. “What are you doing?” I asked. My son turned to me and said thoughtfully, “He doesn’t look like his brains are scrambled.”

When my two children were growing up we never owned a game console, and I limited their video game time to “educational” games. My daughter never did become a huge fan of video games when she went away to college, but my son did and he still is.

Now, looking at the research, I realize I may have been wrong about video games.

Research shows that playing video games isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Training to play action video games increases the speed of perceptual processing and something called perceptual learning. It’s possible to train the senses—vision, hearing, motor skills—and improve their capabilities, especially with action games.

Brian Glass cites research studies showing that when people who are new to video games are taught how to play action games, they can process visual information faster as a result, even outside of the gaming context.

For many decades, it was assumed that the brain has the most flexibility and neurons at birth and that it’s basically downhill from there. There’s the old adage about not consuming too much alcohol, lest it kill the finite number of brain cells you have. Another theory stated that brain structures became more rigid over time—that as people got older, their brains couldn’t be rewired.

This has all turned out to be untrue. The adult brain has neuroplasticity—its neural structures change and keep changing and learning. The skills learned from video gaming are an example of neuroplasticity.

In addition to the perceptual learning that action video games provide, research shows that strategy games (think StarCraft) can also improve cognitive flexibility. Cognitive flexibility is the ability to coordinate four things:

What you’re paying attention to

What you’re thinking about

What rules to use

How to make a decision

The more cognitively flexible you are, the higher your intelligence and psychological health.

So take a break from work and go improve your cognitive flexibility!

Glass, Brian D., W. Todd Maddox, and Bradley C. Love. 2013. “Real-Time Strategy Game Training: Emergence of a Cognitive Flexibility Trait. PLOS One, 7:8(8):e70350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070350.

If you liked this article, and want more info like it, check out my newest book: 100 MORE Things Every Designer Needs To Know About People.

Video Games Increase Perceptual Learning

When my son was about 6 years old, we were shopping one day in a large department store when we walked by a section of demo video games. A group of 10-to 13-year-olds were intensely playing the games and my son was fascinated. I was one of “those parents” who didn’t allow any video games in the house. My son stopped to watch. Not wanting him to get too interested, and also being in a rush to get my shopping done, I said something like, “You don’t want to play video games. See, it’s scrambling their brains.” It’s one of the many nonsensical things that seemed to just come out of my mouth as a busy and distracted parent.

I started walking to the checkout lanes and then realized that my son hadn’t budged. But instead of staring intensely at a video game being played he was now staring at one of the boys playing the video games. “What are you doing?” I asked. My son turned to me and said thoughtfully, “He doesn’t look like his brains are scrambled.”

When my two children were growing up we never owned a game console, and I limited their video game time to “educational” games. My daughter never did become a huge fan of video games when she went away to college, but my son did and he still is.

Now, looking at the research, I realize I may have been wrong about video games.

Research shows that playing video games isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Training to play action video games increases the speed of perceptual processing and something called perceptual learning. It’s possible to train the senses—vision, hearing, motor skills—and improve their capabilities, especially with action games.

Brian Glass cites research studies showing that when people who are new to video games are taught how to play action games, they can process visual information faster as a result, even outside of the gaming context.

For many decades, it was assumed that the brain has the most flexibility and neurons at birth and that it’s basically downhill from there. There’s the old adage about not consuming too much alcohol, lest it kill the finite number of brain cells you have. Another theory stated that brain structures became more rigid over time—that as people got older, their brains couldn’t be rewired.

This has all turned out to be untrue. The adult brain has neuroplasticity—its neural structures change and keep changing and learning. The skills learned from video gaming are an example of neuroplasticity.

In addition to the perceptual learning that action video games provide, research shows that strategy games (think StarCraft) can also improve cognitive flexibility. Cognitive flexibility is the ability to coordinate four things:

What you’re paying attention to

What you’re thinking about

What rules to use

How to make a decision

The more cognitively flexible you are, the higher your intelligence and psychological health.

So take a break from work and go improve your cognitive flexibility!

Glass, Brian D., W. Todd Maddox, and Bradley C. Love. 2013. “Real-Time Strategy Game Training: Emergence of a Cognitive Flexibility Trait. PLOS One, 7:8(8):e70350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070350.

If you liked this article, and want more info like it, check out my newest book: 100 MORE Things Every Designer Needs To Know About People.