Stewart Brand's Blog, page 99

July 27, 2011

Biochronicity

Over the course of a lifetime the human body undergoes various developments at various timescales. There are daily processes such as digestion and sleep, but also decadal processes by which infants mature into adults – undergoing puberty somewhere along the way – and gradually grow old. Biologists have fruitfully studied the mechanisms behind these daily, monthly and yearly sorts of developments, but the factors that actually determine when and how quickly they occur are much less certain.

Wired's Danger Room featured a recently announced effort by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency to investigate those temporal determinants. The Wired blog post explains the agency's 'Biochronicity' project:

There's a hidden clock that underlies every process of every living thing — from when our cells start dividing to how quickly we age. Researchers at Darpa, the Pentagon's extreme science agency, believes they can find it, using a mash-up of biology, code-cracking, mathematics and computer science.

…to uncover the calculus within the genome, it might take some looking beyond the genome. Genes may contribute a few elements to the inner clock, but they interact within a larger scaffolding of cell processes and environmental factors. Furthermore, all those interactions may not be subject to any top-down control of a particular actor. Darpa's "master regulator" may turn out to be more of an interlocking network of systems.

So it appears that the best way to learn about the long-term biological development of a human may be to study a plethora of individual timing mechanisms and the factors that influence them. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency hopes to use such information to predict the course of processes such as cell cycles and aging. The trick, perhaps, will be to come full circle and use knowledge of numerous, distinct yet interdependent mechanisms to paint a holistic and coherent portrait of yearly, decadal or even lifetime development. So it goes with long-term thinking in general. The big picture is composed of – and derived from – small pixels.

The success of this research could have profound implications for long-term thinking in society. Michael West, a scientist who has been studying human aging and cell mortality since the early 1990s, spoke at The Long Now Foundation's SALT series in 02004 about "The Prospects of Human Life Extension," pointing out that an average life-span of 100 years or more would likely change the way that people think about time and how they plan for the future. It was none too many generations ago when few humans lived beyond their forties.

Danger Room writers Noah Shachtman and Lena Groeger are excited and encouraged about the scope of the project.

Biochronicity is a return to the fundamentals, the building blocks of science. Of course, this mission to uncover how time is encoded in our biology will begin with tiny steps. But now could be the perfect time to start.

Long Now Media Update

LISTEN

(downloads tab)

Geoffrey B. West's "Why Cities Keep on Growing, Corporations Always Die, and Life Gets Faster"

There is new media available from our monthly series, the Seminars About Long-term Thinking. Stewart Brand's summaries and audio downloads or podcasts of the talks are free to the public; Long Now members can view HD video of the Seminars and comment on them.

July 26, 2011

Geoffrey B. West, "Why Cities Keep on Growing, Corporations Always Die, and Life Gets Faster"

Superlinear Cities

A Summary by Stewart Brand

"It's hard to kill a city," West began, "but easy to kill a company." The mean life of companies is 10 years. Cities routinely survive even nuclear bombs. And "cities are the crucible of civilization." They are the major source of innovation and wealth creation. Currently they are growing exponentially. "Every week from now until 2050, one million new people are being added to our cities."

"We need," West said, "a grand unified theory of sustainability— a coarse-grained quantitative, predictive theory of cities."

Such a theory already exists in biology, and you can build on that. Working with macroecologist James Brown and others, West explored the fact that living systems such as individual organisms show a shocking consistency of scalability. (The theory they elucidated has long been known in biology as Kleiber's Law.) Animals, for example, range in size over ten orders of magnitude from a shrew to a blue whale. If you plot their metabolic rate against their mass on a log-log graph, you get an absolutely straight line. From mouse to human to elephant, each increase in size requires a proportional increase in energy to maintain it.

But the proportion is not linear. Quadrupling in size does not require a quadrupling in energy use. Only a tripling in energy use is needed. It's sublinear; the ratio is 3/4 instead of 4/4. Humans enjoy an economy of scale over mice, as elephants do over us.

With each increase in animal size there is a slowing of the pace of life. A shrew's heart beats 1,000 times a minute, a human's 70 times, and an elephant heart beats only 28 times a minute. The lifespans are proportional; shrew life is intense but brief, elephant life long and contemplative. Each animal, independent of size, gets about a billion heartbeats per life. (West added that human bodies run on 100 watts—2,000 calories of food a day. But our civilizational energy use adds up 11,000 watts per person. We're like blue whales walking around.)

Does such scalability apply to cities? If you plot, say, the number of gas stations against the size of population of metropolitan areas on a log-log scale, it turns out you get another straight line. Ditto with the length of electrical lines, carbon footprint, etc. Per capita, big city dwellers use less energy than small town dwellers. As with animals, there is greater efficiency with size, this time at a 9/10 ratio. Energy use is sublinear.

But unlike animals, cities do not slow down as they get bigger. They speed up with size! The bigger the city, the faster people walk and the faster they innovate. All the productivity-related numbers increase with size—wages, patents, colleges, crimes, AIDS cases—and their ratio is superlinear. It's 1.15/1. With each increase in size, cities get a value-added of 15 percent. Agglomerating people, evidently, increases their efficiency and productivity.

Does that go on forever? Cities create problems as they grow, but they create solutions to those problems even faster, so their growth and potential lifespan is in theory unbounded.

(West pointed out that there is a bit of variability between cities worth noticing. On the plot of crimes/population, Tokyo has slightly fewer crimes for its size, and Osaka has slightly more. In the U.S., the most patents per capita come from Corvalis, Oregon, and the least from Abiline, Texas. Such variations tend to remain constant over decades, despite everyone's efforts to adjust them. "Exciting cities stay exciting, and boring cities stay boring.")

Are corporations more like animals or more like cities? They want to be like cities, with ever increasing productivity as they grow and potentially unbounded lifespans. Unfortunately, West et al.'s research on 22,000 companies shows that as they increase in size from 100 to 1,000,000 employees, their net income and assets (and 23 other metrics) per person increase only at a 4/5 ratio. Like animals and cities they do grow more efficient with size, but unlike cities, their innovation cannot keep pace as their systems gradually decay, requiring ever more costly repair until a fluctuation sinks them. Like animals, companies are sublinear and doomed to die.

What is the actual mechanism of difference? Research on that continues. "Cities tolerate crazy people," West observed, "Companies don't."

Other media from this Seminar will be posted here.

July 25, 2011

Record-a-thon! This Saturday 7/30

Join us for the Record-a-thon this Saturday July 30 at the Internet Archive and help document and promote the languages used in your own community! We need your help to meet our goal of recording 50 languages in a single day! How many languages can you help us document? Bring yourself and your multilingual friends and be the stars of your own grassroots language documentation project!

Keynote Speaker: Dr. Elisabeth Lindsey, National Geographic

Updated Schedule of Events!

Plan to attend in-person or remotely?

RSVP here through EventBrite!

(Tickets are free – your RSVP will allow us to prepare for numbers to expect and what equipment is going to be present, whether you intend to come in person or if you're participating remotely.)

Svalbard Seed Vault trip report

Svalbard February 02011, (most photos and sound recordings by Steve Rowell)

The Planning:

Over the last couple years artist Steve Rowell has been planning a project to document the Svalbard Global Seed Vault as part of a larger project about the beginnings and future of agriculture. The Seed Vault is designed with a 1000 year design life to store back-up samples of every food crop seed in the world. About a year ago Rowell contacted me to see if Long Now would be interested in participating in his project. I said that we would as long as I got to come along on one of the trips to Svalbard and meet the creators of the Vault. The Norwegian government management of the vault required that Rowell also get participation from Scandinavian nations, specifically Norway as part of his project. Over the last year he was able to secure funding and collaboration with a Norwegian and a Dutch artist, and with it an official invite to visit the Vault. Long Now would cover our accommodations for this scouting trip, and I would cover my own flight. The Seed Vault administrators seem to be a bit overwhelmed with the interest in the Vault. They open the Vault about twice a year to deposit new seed stock and they are apparently inundated with requests to visit. However the remoteness of the location and their limited time on site means they really don't have time to give many tours. But with persistence and the Scandinavian participation Steve was able to secure us the invite. We quickly booked our complicated flights, and found accommodation in one of the few places to stay in winter.

The Journey:

On February 22nd I boarded a Lufthansa jet bound for Munich out of San Francisco. I would be meeting Steve in Oslo the following evening as he was traveling from Washington DC. It took three tries to fly out of Munich due to aircraft difficulties that resulted in me arriving at 1:30 am in Oslo. After a couple hours of sleep I met Steve the next morning at the airport hotel breakfast area, and we boarded our SAS flight to Tromsø at the northern tip of Norway. It was a rare clear day, and I was able to see the stunning fjords of Norway as we crossed the 66th Latitude into the Arctic circle.

In Tromsø we were asked to exit the plane and go through an ID check. I think it has something to do with the unique treaty status of the Spitsbergen Archipelago where Svalbard is. The Spitsbergen Treaty, ratified almost a century ago, gives Norway sovereignty over the area, but they have to grant completely equal access, immigration, and commercialization to any signing nation with minimal taxation. This also means that there are a number of refugees on the island, and I suspect they want to keep track of them.

We re-boarded in Tromsø to find the plane completely packed. Aside from it's major coal mining activity and arctic scientific research, Svalbard is a winter tourist destination to see the northern lights and wildlife. Crammed onto the plane were Swedish grandmothers, Russian coal miners, scientists and even a couple babies. Everyone had shed the usually fashionable northern European winter-wear for serious expedition wear. Huge gore-tex parkas with fur lined hoods and patches reading "Antarctic Survey 1996″ abounded. We landed in 30 mph crosswinds and driving snow. The pilot was clearly used to the airport bringing the plane down fast, but touching down without even a bump. We caught the local bus to our accommodation – Mary-Ann's Polarrigg, and even glimpsed the Seed Vault perched just above the airport.

Longyearbyen:

The town of Longyear was founded by an American from Massachusetts of the same name. He bought the rights to a coal deposit from a Norwegian company and established one of the first permanent outposts on the island. With the coming of the airport in the 70′s, Longyearbyen changed from a tiny mining town to a University town and adventure tourism destination. I will not recount the history of Svalbard in any detail, it is well recorded by many sources including Wikipedia. I do recommend The Future History of the Arctic by Emmerson for anyone interested in the bizarre and increasingly consequential future, present and past of the Arctic region.

Mary-Ann's Polarrigg (entry shown above) known locally as "The Rigg" is a long row of prefab buildings from various eras, mostly leftover from the mining industry. Mary-Ann the proprietor is an amazingly sweet lady who has filled the place with the wildest and weirdest eclectica to be found on Svalbard. Stuffed polar bears and arctic foxes mingle with old mining equipment and incredible historic photos. She is also the chef, preparing hearty Nordic breakfasts and dinners of local seal, trout, reindeer and of course… whale. (In Norway they have t-shirts with a picture of a whale and the tag line "Smart food for smart people".

Our first two bone-chilling days on the island we spent touring around in a borrowed car from Mary-Ann as our appointment at the Vault was not until our third day. There are only a few miles of road there, the longest runs of which service the airport and the coal mines. We got a tour of the Polar University where every student is taught arctic survival and how to use a rifle. Everyone on Svalbard is required to own a gun, and be trained in its use, for protection from polar bears. Svalbard is the first place I have ever seen 20 year old students walking in and out of school with rifles slung over their shoulders.

There is a strange basic irony about Svalbard that we discovered on the University tour. One of the main research topics and political focuses on the island is climate change and atmospheric pollutants. While the Norwegian mainland gets all its electricity from clean hydro-electric power, the only coal fired power plant in Norway is actually on Svalbard. But without this coal power, the island would have to evacuate in less than 48 hours. On Svalbard coal equals life.

The Seed Vault:

Sunday was the scheduled day to visit the Vault, and that morning it was a white out blizzard. We had been told that not even the Royalty of Norway were allowed in the actual seed vault, and to expect to only see the entry hallway. Our guide at the University, a few days before, was shocked that we would even be allowed to see the hallway. The drive up the switchbacks was a bit perilous in the snowstorm. We had to stop multiple times as visibility dropped to zero. We met our hosts Roland von Bothmar and Anders Nilsson of NordGen at the top of the road, and together approached the vault. Apparently they had spent a lot of time the previous day cracking and melting ice off the door as it had been above freezing allowing water to run down, and then freezing the door shut as the evening temperatures dropped. (Note that there is a lot value to a design that sheds water away from hinges, seems, and especially locks.) Their work had paid off though as they were able to open the door quickly and we all scrambled in out of the nearly horizontal snow stinging our faces.

The 320 feet of fluorescent lit down sloping entry hallway is separated into three equal sections. This first section we enter into from the outside door is not completely sealed off from the outside air. You can see where the permafrost meets the building in a sloping line of hoarfrost built up on the wall. We move deeper toward the next door. Roland asks us to watch out for the ice on the floor, apparently the freeze thaw cycle melts the frost on the walls which then runs down the floor and then freezes again, making the ramp treacherous.

On the other side of the door the hallway widens to a 20 foot diameter corrugated metal tube with a concrete floor. Roland explains that this part of the vault has been shifting as the permafrost around us thaws and freezes. Indeed the concrete on one side of the floor is cracking as evidence of this. The wall at the end of this section is a new addition and is still covered in a tyvek like building wrap.

Once through this next doorway the floor curiously transitions to asphalt, possibly to allow more flexibility and water permeability. There is a pump system and grating newly installed in the floor to deal with the water from the thawing frost. All of these water and freeze-thaw issues have been discovered since the vault was finished in 02008. The walls and ceiling of this section are about 25 feet wide and tall. The very rough surface is a product of the drilling and blasting into the loose local shist. The rock has been stabilized with large bolts roughly every 4′, covered in shot-crete, and then a white paint. This wall, ceiling and floor finish is the same for the rest of the vault, including the seed chambers. This hallway terminates in a large concrete wall with a metal door in it, and there are a few other doors on the right hand side at the end of the hall. Above are cable racks and the ever present ventilation tubes. One set of the tubes has frost building up on each joint section, these are the cooling pipes for the seed vault bringing them down from today's ambient -5C to the desired -18C. We enter the doors on the right into a control room. This area has desks and a PC and a sign in book. The list of people who have signed in is impressive, Everyone from UN president Ban Ki-moon to President Jimmy Carter, and… us. I had assumed this was as far as we were going to get, but then Roland says that he is turning the lights on in the next section for us, and warns that camera lenses brought into the colder areas will fog up. We leave a selection of lenses here, and pass through the third lock. (Sound recording in the last hallway section)

Through the doors the asphalt starts sloping back upward and we enter into a lateral access hall where you can see each of the three seed vault doors. The doors are embedded in concrete walls blocking off each rough blasted chamber. The central chamber, vault 2, is covered in a thick layer of frost, cracked away around the door from the recent depositing of this years seed stock. The cooling pipes above are fully covered in thick frost here as well. The only adornment in the whole space is a spear-like metal shape on the wall, a seed sculpture by a Japanese artist who donates these pieces to seed banks all over the world.

There is a shelf here with some plastic bins and seed samples of the types found in the vault. Glass jars, vials and bags each containing labeled seeds from different seed banks around the world. Now they use a standardized mylar zip lock bag and plastic bin. However Roland points out the USDA submissions always use their own box, a cardboard one. It turns out that this seed vault is the second one on Svalbard. There was one created in the 01980s for just Scandinavian species which is inside a shipping container in one of the old coal mines. It was sealed 30 years ago and Roland hasn't even been there. Roland explains that all the seeds arrive by cargo plane a week ahead of each deposit, upon arrival they use the airport x-ray machine to make sure there are only seeds being deposited (e.g. no bombs). In the last 3 years since the vault opened they now have over 637,000 varieties in the vault, and they have not even filled up one chamber yet. Roland also confirms what we learned from the University, that all the seeds here are edible crop seeds with one exception. Through a partnership with the University at Svalbard they have stored about 60 varieties of plants from the Spitsbergen Archipelago, none of which are edible.

Roland also mentioned all the crackpot theories and stories people have about the vault – like the one where it is really all the big bio-tech companies trying to control the world food supply. These of course are not true in the least. It is a Norwegian government project run by a consortium of academic, government and non-profit scientific entities. The seeds remain the property of each donating country, and the manifest is public (you can go to the website and download it now if you like). Depositors can pull their seeds at anytime for any reason. So far no company has submitted GMO seeds, likely because of how much disclosure they would have to do around them as part of the process. The really interesting question though is what happens if a country ceases to be a country, who then owns the seeds and the rights to access them? (Sound recording in the transverse tunnel)

Roland opens one of the empty vaults for us. We shuffle into the air lock area and after the outer door is closed, the next door is opened. This vault, number three, has no seeds or cooling system. It is about 100 feet deep and 30 feet wide and tall. Some of the same shelving used in the active vault is in here, along with the plastic bins ready for more seeds to be delivered. Amazingly the thick stone wall shared with the active vault two is covered in frost. Wires dangle from sensor equipment on each wall, and there is one spot you can see the fractured native shist where the shot-crete doesn't quite meet the floor. We also go into the other empty vault, number one, and it is similar, except it is completely empty. We ask if the spaces were sterilized or treated in any way before the seeds go in. Roland says that they are not, and that the mylar bags and the cold are all the seeds need.

Then to our surprise, Roland offers to open the active vault. Jimmy Carter wasn't even allowed into that vault. We crowd close to the ice covered door, we need to let as little cold air out as possible. Roland unlocks the door with one of only four keys in the world, and we hear the frost crack at the hinges.

We rush into the airlock, and the next door is opened. This vault is COLD. The difference between -5c and -18c (0F) is palpable. The inside of my nostrils hurts and the skin on my face tightens. Most of the space near the door is taken up by the cooling equipment. Apparently this equipment was installed just 6 months ago to replace the original equipment that was less efficient, loud and blustery. Ten feet in front of us is a locked gate, and ten feet beyond that are the shelves and shelves of boxes. Each box is marked with the logo of a seed bank from a different nation, the USDA cardboard boxes are front and center in the second row of shelves. We are allowed a few photos and video and are ushered quickly back out again.

After the visit I read some of the material we received. It doesn't go too much into the "why" of things, just what happened in the building process. But what was apparent was that they had a very tight deadline, and I am not sure why. Most of the decisions, location, contractors, and material choices were made solely for this expediency. While it will likely be okay if people are there to maintain it, it seems some of the issues like the shist rock site, ferrous metal reinforced concrete, permafrost shifting and flooding, may require a lot of intervention to maintain the integrity of the vault.

I certainly learned a lot being here. Mainly that even if you put your site in the hardest to reach place in the world, people will still want to come and visit it – in droves. They did not design it for visiting, and are having to deal with this fact now.

We ended the day with a dinner up at Huset, the most northerly restaurant with a Michelin star. We ate scallops and reindeer with Roland and Anders as well as a seed scientist from University of Arizona who was in town to deposit their collection of desert legume seeds from around the world. What an amazing day.

Other Travel Notes:

Our last day here we finally got an opening in the weather. We arranged a guided "skooter" (snowmobile) tour and our original plan was to visit the Russian coal outpost of Barentsburg, but after talking to some folks we switched it over to Temple Fjord. I cannot recommend touring Svalbard this way enough. We even saw the direct sun for the first time since our arrival when out on the fjord. Be prepared for cold unlike anything you have ever experienced. Under the thick "skooter suit," boots and helmet loaned to me by the guide I wore: expedition weight base layers, a complete down suit, a fleece, two pairs of thick socks, a neck gator and a balaclava. I still got chilled to the point of numbness. Any small chink in your armor, and the wind augmented by 50km/hr on the scooter cuts right to your bones. We encountered a dutch two masted sail boat that purposefully traps itself in the sea ice each year there. They operate it as a kind of outback adventure hotel. Do not miss touring these outer areas, they are spectacular.

Some notes about clothing. The Norwegian tradition of removing your "outside shoes" is honored almost everywhere on Svalbard. Bring snow boots that are easily removable, and carry some slippers or flip flops around with you so you don't end up in your socks everywhere. The other pro-tip is to bring a pair of ski goggles with clear lenses (not dark tinted as you wont be able to see). Even if you are walking 500 yards, you will be glad you did in a snow storm. As you might expect bring lots of down, fleece and gore-tex layers. Neck gators, balaclavas, mittens and glove liners are also a must. It can rain, snow, blow 40 mph, and then turn to sunshine all within an hour. Headlamp and even a little red flashing jogging light is also a great idea for walking around after dark (eg. after 3pm).

There are some excellent eating and drinking establishments on Svalbard. The Michelin starred Huset up high in the valley is astonishingly good, (but pricey) and includes a wine list of over 1100 titles. Also the pub in town next to the market has one of the largest single malt whiskey collections in all of Europe, not to be missed. You should also stop by the Svalbard Museum, it has won several well earned exhibit design awards. Likely one of the most interesting and informative small museums I have ever been to.

A general note that if coming in winter (which I do recommend) that you put at least a day or two of float in your schedule. While you can do most things even in the worst weather here, it seems a bit silly to tour the fjords when you have 20 feet of visibility. Also note that there are 4 months of the year where there it basically as dark as night. We had plenty of indirect light on our trip at the end of February.

Living and travel costs in Scandinavia are expensive, but Svalbard is even more so. Pretty much everything aside from water, reindeer, and polar bears has to be imported by air to Svalbard. A personal pizza and drink can easily run $20-30, a simple dinner for two and a couple beers can come in well over a $100. Simple accommodations even in the slow season are hard to book and expect to pay over $150-300/night. The Polarrigg was nice as they have a full kitchen for guest use, and Mary-Anne let us use her vehicle several times at no charge. There is a Radisson which is very central, a huge benefit as its a very short walk to most local services (you can walk from the Rig as well but it's about 1/4 mile in often bad weather). The funny thing though is some things cost less than on the mainland because of the unique tax status of Svalbard. Alcohol is much cheaper here, basically US prices.

Like many Scandinavian and northern areas where alcoholism is rampant, the state controls the liquor stores here. However Svalbard has the most control I have ever seen. There is one liquor store, and each citizen's purchases are allocated and recorded. In addition visitors must present their plane ticket on which they write what you have bought to be sure you do not go above your personal allocation while there. You can fly in with liquor though…

July 15, 2011

Brains, Lead, and the Law

Long Now Board Member David Eagleman recently wrote an article for The Atlantic exploring the problems brain science is creating for our legal system's underlying conceptions of free will, intention, and culpability:

The crux of the problem is that it no longer makes sense to ask, "To what extent was it his biology, and to what extent was it him?," because we now understand that there is no meaningful distinction between a person's biology and his decision-making. They are inseparable.

WHILE OUR CURRENT style of punishment rests on a bedrock of personal volition and blame, our modern understanding of the brain suggests a different approach. Blameworthiness should be removed from the legal argot. It is a backward-looking concept that demands the impossible task of untangling the hopelessly complex web of genetics and environment that constructs the trajectory of a human life.

Instead of debating culpability, we should focus on what to do, moving forward, with an accused lawbreaker. I suggest that the legal system has to become forward-looking, primarily because it can no longer hope to do otherwise. As science complicates the question of culpability, our legal and social policy will need to shift toward a different set of questions: How is a person likely to behave in the future? Are criminal actions likely to be repeated? Can this person be helped toward pro-social behavior? How can incentives be realistically structured to deter crime?

It's clear from this article that there's much to learn and maybe even more to do in changing our legal system and our understanding of justice, but Jonah Lehrer has a serendipitously-timed blog post that makes tangible the kinds of benefits we stand to gain:

The steep drop in crime in America is one of the most noteworthy sociological trends of the last twenty years. What astonishing is that, although the murder rate has fallen by more than 50 percent in many cities, we still don't know why.

He points out that one piece of the puzzle could be the banning of lead in paint by the Environmental Protection Agency.

Lead exposure damages the prefrontal cortex – a part of the brain associated with impulse control. So, it follows that once there were many fewer children experiencing loss of impulse control due to lead exposure, there would be many fewer impulsive people in our society likely to commit crimes in heated moments.

This remains a theory, but as an example of a positive outcome from policy-making based in an empirical understanding of the brain, we can only hope it's the first of many.

July 14, 2011

Evolvability and 50,000 Generations of E. Coli

Adapting to one's environment may be essential to survival, but environments themselves change, and retaining adaptability can mean the difference between short- and long-term success. A team of researchers was recently able to observe and analyse the benefits to bacteria of different mutational strategies along these lines.

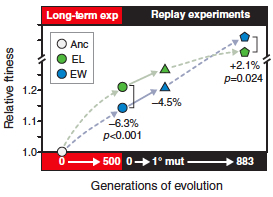

The key was an ongoing experiment utilizing 50,000 generations of E. Coli. Using this repository of data, researchers with the Universities of Michigan and Houston were able to look at various strains of the E. Coli bacteria and watch as they adapted, diverged, competed with each other, and met different fates over hundreds of generations. The results were surprising – lineages within the population that quickly adapted to the experimental environment (and were, in direct competition, more fit than the others) fared, in the end, worse than those that took their time.

In essence, the ELs [Eventual Losers] followed a trajectory in the fitness landscape that allowed more rapid improvement early on, but which shut the door on at least one important avenue for further improvement. By contrast, the EWs [Eventual Winners] followed a path that did not preclude this option, giving them a better than otherwise expected chance of overtaking the ELs.

Eyes on the prize, little E. Coli – even microbes have to think long-term some of the time.

The Scientist has an article summarizing the study, or you can find the paper itself through Science.

July 12, 2011

Long Now Media Update

WATCH

Peter Kareiva's "Conservation in the Real World"

There is new media available from our monthly series, the Seminars About Long-term Thinking. Stewart Brand's summaries and audio downloads or podcasts of the talks are free to the public; Long Now members can view HD video of the Seminars and comment on them.

Bringing Ancient Sculpture Back to Life

An exhibit currently on display at Stanford University's Cantor Arts Center resurrects a liveliness rarely associated with Ancient Greco-Roman sculpture. When asked to conjure an image of Roman décor circa the year zero, sparkling white marble generally abounds. It turns out that a closer look at these millennia-old figures reveals that they were once covered in vibrantly-colored paints. In an article about the exhibit, Stanford News describes how undergraduate student Ivy Nguyen used ultra-violet light to find trace amounts of pigment on the surface of ancient sculptures, still present after over two thousand years:

While the technique is not new, Nguyen went beyond that with the use of x-ray fluorescence (XRF), commonly used in conservation sciences. XRF can find traces of pigment that are invisible to the unaided eye.

Nguyen's ultraviolet imaging with the black light reveals "ghost images," showing the areas that might be promising to test. The XRF reveals what's in those ghost images.

Although other exhibitions have focused on painted Greek and Roman statues, this exhibition focuses on the science as well as the art, taking the visitor through the laboratory process with cases displaying pigments used in ancient times, wall-mounted images of the analysis and small, painted terra cotta works from Cantor's ancient collection that were used as controls in the study.

Two versions of a restored sculpture are on display at the exhibit. One version includes colors that were found through testing while the other, taking into consideration that only base layers of paint have survived, includes additional layers of painted decorations that may more closely resemble the originals.

Through some combination of the quality of ancient pigment and the creative application of modern scientific technology we find ourselves able to catch a more accurate glimpse of a civilization long fallen. To see the painted replicas of Stanford's Maenad sculpture (and to get some ideas about what materials to use for your next paint job), visit the Cantor Arts Center, which is free to the public. The exhibit ends on August 7th.

July 9, 2011

Life is better after World War III?

The folks over at Good put together an info-graphic on survey results of what Americans think the world will be like 02050. Click on the picture above to see the big version. It is interesting that while overall optimism seems to be on the decline (since the last survey in 01999), the majority of Americans are optimistic about their personal future, while also believing that World War III and a terrorist nuclear attack are all likely. Where do you land on these questions? Will 02050 be better or worse that 02011?

Stewart Brand's Blog

- Stewart Brand's profile

- 291 followers