Stewart Brand's Blog, page 92

March 2, 2012

Language: Speed vs. Density

The September 02011 issue of the journal Language included an article entitled "A Cross-Language Perspective on Speech Information Rate," by a team of linguists working with the University of Lyon and the French National Center for Scientific Research. Like many linguistic studies, this one investigates the parameters of human language and seeks to identify commonalities that hold true across languages. Given, however, that universal grammatical rules have proven more difficult to define than linguists might have hoped, this study was designed to test the universality of a different factor – time.

The authors hypothesize that "a trade-off is operating between a syllable-based average information density and the rate of transmission of syllables in human communication." Basically, a language that is spoken quickly – in terms of syllables per second – uses more syllables than one that is spoken slowly in order to say the same thing.

To test their hypothesis they analyzed audio recordings of native speakers of seven different languages reading brief texts written in various styles. There were twenty texts, each composed in English and translated into the other languages. The authors compared the number of syllables that each language used in a given text, as well as the amount of time taken by speakers of different languages to actually say the entire texts. And indeed, they found that for the most part the languages whose texts used more syllables were spoken faster, and vice versa, resulting in equivalent rates of information output. Two complementary strategies for encoding and transmitting ideas.

"One has to consider the [...] loose hypothesis that [the information rate of the language] varies within a range of values that guarantee efficient communication, fast enough to convey useful information and slow enough to limit the communication cost (in its articulatory, perceptual, and cognitive dimensions)."

The premise here is that each translation of each of the texts communicates all of the information communicated in each other translation, adding and subtracting nothing, simply encoding the information according to the rules of each language. It would be interesting to discuss this premise with respect to the notion of linguistic relativity, which argues that your native language actually influences the way you perceive reality. Or in terms of issues such as evidentials or honorifics, which can require that certain information – and therefore more syllables – be included in a statement which in another language might be superfluous. Further research might also be able to analyze across more language families. The seven languages used in this study were English, German, French, Spanish, Italian, Mandarin Chinese and Japanese.

The authors also noted that the syllables themselves in quickly spoken languages are on average less complex, in that they are composed of fewer sounds (i.e. 'law' vs. 'claw' – both one syllable, but with different numbers of phonemes). As an initial investigation into the speed with which people communicate through speech, this is a fascinating study.

It seems that humans may be naturally and universally self-regulating when it comes to communicating through speech. There is a balance that cannot be disturbed: fast syllables are not allowed to carry too much meaning, and syllables with lots of information must be spoken slowly.

via kottke.org

March 1, 2012

Jim Richardson Seminar Media

This lecture was presented as part of The Long Now Foundation's monthly Seminars About Long-term Thinking.

This lecture was presented as part of The Long Now Foundation's monthly Seminars About Long-term Thinking.

Heirlooms: Saving Humanity's 10,000-year Legacy of Food

Wednesday February 22, 02012 – San Francisco

Audio is up on the Richardson Seminar page, or you can subscribe to our podcast.

*********************

Save Agricultural Biodiversity - a summary by Stewart Brand

Humanity's agricultural legacy is on a par with any of our great cultural legacies, Richardson said, but preserving it is not just a matter of honoring the history and richness of our most fundamental civilization-enabling technology. For the health of future crops and livestock we need the deep genetic reservoir of all those millennia of sophisticated breeding. A million people died in the Irish Potato Famine because the whole nation depended on just two varieties of potato. In Peru, where potatoes originally came from, Richardson visited a field at 14,000 feet where 400 varieties of potato (with names like "Ashes of the Soul" and "Puma Paw") are grown in just two acres. The local 1,300 varieties of potato are managed by a "Guardian of the Potatoes," whose job it is in the community to know the story and uses of all the potatoes.

The accumulated wisdom in the crops and livestock is profound. We've been breeding cattle for 10,000 years, goats for 9,000 years, dogs for 12,000 years, chickens for 8,000 years, llamas for 6,500 years, horses for 6,000 years, camels for 4,000 years. All those millennia we have been in deep partnership with the animals. All of our staple foods are ancient. Wheat has been bred for 11,000 years, corn for 8,000 years, rice for 8,000 years, potatoes for 7,000 years, soybeans for 5,000 years

"For 9,900 years," Richardson said, "we've been building up variety in domesticated crops and livestock—this whole wealth of specific solutions to specific problems. For the last 100 years we've been throwing it away." 95% is gone. In the US in 1903 there were 497 varieties of lettuce; by 1983 there were only 36 varieties. (Also changed from 1903 to 1983: sweet corn from 307 varieties to 13; peas from 408 to 25; tomatoes from 408 to 79; cabbage from 544 to 28.) Seed banks have been one way to slow the rate of loss. The famous seed vault at Svalbard serves as backup for the some 1,300 seed banks around the world. The great limitation is that seeds don't remain viable for long. They have to be grown out every 7 to 20 years, and the new seeds returned to storage.

Even with living heirlooms, the rule is Use It Or Lose It. Devotees of exotic cattle say "You have to eat them to save them." With dramatic photos Richardson compared the livestock shows in Wales with the livestock markets in Ethiopia. You see children adoring the young animals and breeders obsessing on details of excellence and uniqueness. "One guy says, 'You see that sheep with the heart-shaped spot on his left shoulder? I'll bet you I can move it to his rump in four generations.'" There's a sheep called the North Ronaldsay that is bred to live solely on seaweed on the coast. Ethiopia has some specialists, like the Sheko cattle that are resistant to tsetse flies, but unlike in Europe, most of their breeds have to be generalists capable of providing meat, milk, labor (such pulling plows), and warmth in the winter.

Helping preserve agricultural biodiversity is open to anyone. The Seed Savers Exchange in Decorah, Iowa, has 13,000 members. Their catalog is a cornucopia of heirloom garden delights, and members learn how to produce and store their own seeds and then share them. "It's a wonderful example of citizens participating in the process." And we can always acquire a new taste for old foods. Teff! Quinoa! Amaranth! Randall Lineback cows! You have to eat them to save them.

PS: Jim Richardson's beautiful heirloom photos and article may be found here.

Subscribe to our Seminar email list for updates and summaries.

February 29, 2012

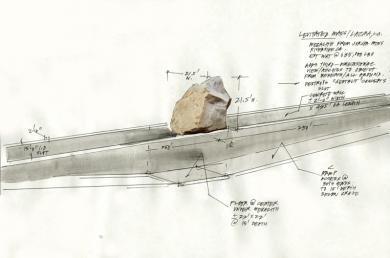

Heizer's Mass Takes the Scenic Route

Theories about the construction of Stonehenge, Easter Island's Moai, or the Egyptian pyramids range from the mundane to the outrageous, so trying to imagine what people thousands of years from now will make of the above diagram – or the 340-ton boulder relocation project it represents – may be a futile exercise. Regardless, it's a pretty safe bet that Levitated Mass, the artwork by Michael Heizer for which such a strange machine is needed, will be around for a while. Will the journey it's taking over the next 10 days be shrouded in myth and mystery generations hence? That depends, at least in part, on Twitter's usefulness to future archaeologists – the rock is documenting its trip via tweet.

Sourced from a quarry about a hundred miles from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, where it will live out its days, the boulder will travel through four counties and 22 cities. Along the way, it will require roads to be closed, paths to be cleared and street signs and overhead wires to be temporarily removed in order to make way for its massive, custom-built transporter. The LA Times is following the project, as is Unframed, LACMA's blog.

February 27, 2012

Mark Lynas Seminar Primer

Tuesday March 6, 02012 at the Cowell Theater, San Francisco

Journalist and environmentalist Mark Lynas has a knack for getting deep down into the crux of problems and scraping out the science. Though we shouldn't ever mistake a clear view for a short distance, this knack is making the terrain between us and a sustainable, thriving biosphere look pretty navigable. Much of his writing has focused on finding ways to objectively measure, at personal and global scale, our relationship with the environment.

He may be best known for his book Six Degrees: Our Future on a Hotter Planet, in which he explores the ecological changes humanity can expect if Earth's average temperature rises as much as the IPCC predicts it might over the next century.

In his most recent book, The God Species: How the Planet Can Survive the Age of Humans, he places climate change within the context of the nine planetary boundaries, a fairly new ecological framework for assessing the health of our biosphere. Much as we are able to identify and assess the nervous system as distinct from (but intertwined with) the circulatory system, the digestive system, the endocrine system, etcetera, we're beginning to better understand the distinctions and interrelations between our planet's climate, oceans, geology, and biodiversity. Scientists have identified nine of these systems and boundaries beyond which they begin destabilizing each other, leading to a biosphere that can no longer support a global human civilization.

Lynas served for two years as climate science advisor to the (now deposed) president of the Maldives, a low-lying island nation that was taking climate change seriously enough to have explicitly set the goal of becoming carbon neutral by 02020. (The archipelago hasn't got any land more than 6 feet above sea level, so climate change and rising waters represent a rather immediate existential threat to them.) Now that president Nasheed has been removed via coup, however, it's unclear how devoted the government will remain to that goal. While there, though, Lynas helped them asses and make partnerships around alternative energy and other emissions-reducing technologies.

As we're coming to terms with the Anthropocene, a good understanding of our actions' impacts is vital. Mark Lynas has been following the scientists working to develop that understanding and his Seminar will offer a distillation of how we can track the biosphere's health. The talk is on Tuesday March 6th at the Cowell Theater. You can reserve tickets, get directions and sign up for the podcast on the Seminar page.

Subscribe to the Seminars About Long-term Thinking podcast for more thought-provoking programs.

PanLex joins Rosetta at Long Now

PanLex, the newest project under the umbrella of The Long Now Foundation, has an ambitious plan: to create a database of all the words of all of the world's languages. The plan is not merely to collect and store them, but to link them together so that any word in any language can be translated into a word with the same sense in any other language. Think of it as a multilingual translating dictionary on steroids.

You may wonder how this is different from some of the other popular translation tools out there. The more ambitious tools, such as Babelfish and Google Translate, try to translate sentences, while the more modest tools, such as Global Glossary, Glosbe, and Logos, limit their scope to individual words. PanLex belongs to the second, words-only, group, but is far more inclusive. While Google Translate covers 64 languages and Logos almost 200 languages, PanLex is edging close to 7,000 languages. With the knowledge stored in PanLex, translations can be produced extending beyond those found in any dictionary.

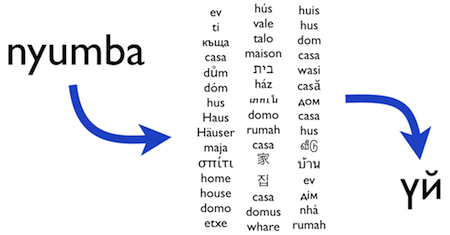

Here's an example to give the basic idea of how it works. Say you want to translate the Swahili word 'nyumba' (house) into Kyrgyz (a Central Asian language with about 3 million speakers). You're unlikely to find a Swahili–Kyrgyz dictionary; if you look up 'nyumba' in PanLex you'll find that even among its half a billion direct (attested) translations there isn't any from this Swahili word into Kyrgyz. So you ask PanLex for indirect translations. PanLex reveals translations of 'nyumba' that, in turn, have four different Kyrgyz translations. Three of these ('башкы уяча', 'үй барак', and 'байт') each have only one or two links to 'nyumba'. But a fourth Kyrgyz word, 'үй', is linked to 'nyumba' by 45 different intermediary translations. You look them over and conclude that 'үй' is the most credible answer.

How confident can you be of your inferred translation—that Swahili 'nyumba' can be translated into Kyrgyz 'үй'? After all, anyone who has played the game of "translation telephone" (where you start with Language A, translate into Language B, go from there to Language C and then translate back to Language A) will know this kind of circular translation can result in hilarious mismatches. But PanLex is designed to overcome "semantic drift" by allowing multiple intermediary languages. Paths from 'nyumba' to 'үй', for example, run through diverse languages from Azerbaijani to Vietnamese. Based on such multiple translation paths, translation engines can provide ranked "best fit" translations. As the database grows, especially in its coverage of "long tail" languages, possible translation paths will multiply, boosting reliability.

There are a couple of demonstrations that you can try with a browser. This will give you a sense of the magnitude of the data and the potential power of the database as a tool. One of these is TeraDict. If you enter a common English word like 'house' or 'love' you are likely to get translations into hundreds, or even thousands, of languages, and in some cases many translations per language. French, for example, has 25 translations for 'house' and 55 translations of 'love', including 'zéro' (hint: Think tennis!). Two similar interfaces allow you to explore the database in either Esperanto—InterVorto—or Turkish—TümSöz.

The second web tool, PanLem, is considerably more complicated and is used mostly by PanLex developers to enlarge and evaluate the database. But it's publicly accessible. There is a step-by-step "cheat sheet" to help you climb the learning curve.

PanLex is an ongoing research project, with most of its growth yet to come, but the database already documents 17 million expressions and 500 million direct translations, from which billions of additional translations can be inferred.

PanLex is being built using data from about 3,600 bilingual and multilingual dictionaries, most in electronic form. The process of ingesting data into the database involves substantial curation and standardization by PanLex editors to ensure data quality. The next stage of collection will likely involve dictionaries that exist only in print form. It is hard to say how many are out there, but we expect it is on the order of tens of thousands. It is likely that most of these have not been scanned or digitized. Once they are, there will be a significant effort to improve the optical character recognition (OCR) for these materials—an effort which is likely to be highly informative to the development of OCR technology, since it will involve the human identification of many forms of many different scripts for languages around the world.

PanLex is working closely with the Rosetta Project. PanLex is a wonderful realization of the Rosetta Project's original goal in building a massive, and massively parallel, lexical collection for all of the world's languages.

February 22, 2012

The Future of Film's Past

Science fiction author Bruce Sterling, who delivered one of our earliest SALT presentations, recently shared an article about the difficulties of film preservation on his Wired blog, beyond the beyond.

In the article, Kristin Thompson and David Bordwell describe the enormous and myriad challenges that film archivists face, from physical and digital decay, multiplicity of formats, sheer volume of footage, cost of preservation, and a general disregard for 'preservability' in the film industry's production process.

The authors begin with the story of Dawson City, where a cache of films buried in 1929 was recently found, leading to some amazing restorations. But as digital footage becomes the norm, the stability inherent in 35 mm film (upwards of a 100-year life-span with proper care) is no longer a guarantor of longevity.

Given such discoveries, the archivists will set to work creating usable and enduring versions. But today such a task is much harder. Soon most of the films we make and show will not exist on photochemical stock. They'll be digital files, and they need to be kept securely. But how?

Will today's typhoon of ones and zeroes rip away our analog past? Will there ever be a digital Dawson City, a stockpile of files of lost movies? It seems likely that digital projection has, in unintended and unexpected ways, put the history of film in jeopardy.

Even when people recognize the severity of the problem, the cost of doing anything about it is steep. An EU archival commission estimates the cost of basic archiving for Europe's yearly film output in 02015 at 1.5-3 million euros, with 1,900 petabytes of data and another 290 million euros to ensure long-term preservation. To archive the Library of Congress' 30,000-title nitrate collection alone would require 1.44 exabytes of data storage.

Now let's say you've not only recognized the problem, found the funding to act on it, and archived a film. "What if," the authors ask, "you want to show it tomorrow? Or ten years from now? Or fifty?"

If you have a DCP [Digital Cinema Package] in good shape, and a projector that will show 2K/4K according to the Digital Cinema Initiative standard, you're good to go. For now. But maybe not tomorrow. [...]

The digital gold rush, along with fear of piracy, favored short-term solutions and proprietary, incompatible software and hardware. There were too many ephemeral video formats chasing the consumer and prosumer market, with little thought of their afterlives. The days of 8mm, super-8mm, 16mm, 35mm, and 65/70mm were simple by comparison. We're left with a plethora of transitory standards that will be impossible to recover.

The tradeoffs between these standards – both digital and chemical – present a dizzying array of problems and opportunities that the article explores in much further detail. At the end is a long list of links and resources for anyone interested in digging deeper into the issue.

February 20, 2012

Francis Gavin On the Use (and Misuse) of History in Political Decision-Making

Policy-makers wrestling with foreign policy decisions that will have very long-lasting repercussions often turn to experts to inform them of the likely outcomes.

Through the lens of the current international dilemma over Iran's nuclear ambitions, foreign policy historian (and former SALT speaker) Francis Gavin offers his thoughts on the relationship between policy-makers and experts in an article for Foreign Policy written with James B. Steinberg.

Crafting policy requires a certain amount of implicit prediction about the future, which is – to put it lightly – notoriously difficult to do right:

"In fact, as Philip Tetlock demonstrated in Expert Political Judgment, a 20-year study that looked at over 80,000 forecasts about world affairs, self-proclaimed authorities are no better at making accurate predictions than monkeys throwing darts at a dart board, and they are rarely held accountable for their errors."

While exploring some of the past decisions made as part of US nonproliferation efforts, he shows that historians can easily choose individual precedents that belie the larger portfolio of issues faced during their time and the broader strategy into which they may have fit. Taking the full context of the time, the issues and the decision-makers is necessary to properly extracting any useful historical knowledge from past events:

"If Vietnam is understood at least in part as a function of the Johnson administration's successful efforts to encourage nuclear nonproliferation, seek détente and cooperation with the Soviets, and manage the German question, the policy — if still disastrous in its consequences — makes more sense. The difficulty inherent in assessing U.S. foreign policy is made clear by the fact that all three policies were crafted by the same policymakers in the same administration at the same time."

But, rather than simply taking "experts" down a peg for ignoring the broader range of issues policy-makers must consider, he suggests a way to make better use of their specialties:

"We believe that if different types of experts — the best strategists and historians, for example — were brought together with statesmen in an environment that encouraged honest debate and collaboration and not point-scoring, where participants were encouraged to acknowledge how little anyone can actually know about the future effects of U.S. actions, the possibility to achieve both greater coherence and greater humility in the U.S. foreign-policymaking process would be greatly enhanced."

February 16, 2012

Time in the 10,000-Year Clock

Keeping time for 10,000 years isn't tricky just because its hard to build a really durable clock. It also forces us to recognize and account for changes in things we normally think of as immutable, like the length of a day.

Long Now co-founder and lead designer of the 10,000-Year Clock, Danny Hillis, published a paper recently along with Rob Seaman, Steve Allen, and Jon Giorgini, with the American Astronomical Society. The paper discusses the different kinds of time that the Clock needs to track in order to show accurate time for the next ten millennia, and how these systems interrelate.

The 10,000-Year Clock has both a pendulum (generating an approximation of absolute time) and is also synchronized to the sun at noon. Therefore the Clock must reconcile Universal Time, Terrestrial Time, and Barycentric Dynamical Time and also deal with unpredictable changes in the Earth's rotation:

"The variation is caused by a variety of effects including tidal drags, shifts in the Earth's crust, changes in ocean levels, and even weather… This creates an uncertainty in the average length of day of about 10 parts per million, an uncertainty of plus or minus 37 solar days over the design lifetime of the clock."

So, not accounting for these variations could theoretically leave the Clock over a month off at the end of 10,000 years. Read the paper to see how each system is accounted for.

The paper was presented at a colloquium in October 02011 called Decoupling Civil Timekeeping from Earth Rotation. Attendees, including astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson, discussed the paper and the 10,000-Year Clock. Notes taken during the conversation show that, while the technical success of the Clock's durability is yet to be determined, its ability to inspire long-term thinking is already taking hold:

Neil deGrasse Tyson jested that the Long Now should put some signage on the 10,000 Year Clock so that a post-apocalyptic Earth will not think that the world will end when the clock stops working.

February 13, 2012

Mark Lynas Seminar Tickets

Seminars About Long-term Thinking

Mark Lynas on "The Nine Planetary Boundaries: Finessing the Anthropocene"

TICKETS

Tuesday March 6, 02012 at 7:30pm Cowell Theater at Fort Mason

Long Now Members can reserve 2 seats, join today! • General Tickets $10

About this Seminar:

Human activities increasingly dominate 9 crucial planetary systems. Add to the familiar ones—climate, biodiversity, and chemical pollution—atmospheric aerosols, ocean acidification, excess nitrogen in agriculture, too much land in agriculture, freshwater scarcity, and ozone depletion. To have "a safe operating space for humanity" on Earth requires adjusting our behavior to work within those systems. How we collectively step up to that responsibility will determine whether "the Anthropocene" (the current geological era shaped by humans) will be a tragedy or humanity's greatest accomplishment.

British environmentalist Mark Lynas is the author of one of the finest climate books, Six Degrees, and of a new work, The God Species: How the Planet Can Survive the Age of Humans, which spells out a cohesive Green program for this century guided by the 9 boundaries.

Twitter - up to the minute info on tickets and events

Long Now Blog – daily updates on events and ideas

Facebook – stay in touch through our fan page

Long Now Meetups - join one or start your own

February 9, 2012

Jim Richardson Seminar Primer

Wednesday February 22, 02012 at the Cowell Theater, San Francisco

Jim Richardson's photography focuses heavily on humanity's relationship to the natural world. He often travels far and wide to explore distant locations, working for both National Geographic and Traveler Magazine, but he's also lovingly documented life in his own backyard of rural Kansas.

He'll be speaking in an upcoming Seminar About Long-term Thinking about the biodiversity created by human agriculture. Though industrial monoculture threatens this rich legacy, humans have spent considerable time and effort over the last 10,000 years breeding and cross-breeding plants and animals of every color, stripe and shape. These heirlooms will require their own conservation efforts and documenting them photographically is a task Jim Richardson is highly qualified for.

In an interview for The Comment Factory, he discussed the proliferation of digital photography and the ways it has lowered many photographic boundaries. He reminds us, though, that, "Technology alone is never enough. Meaning comes from people. Technology without meaning is just a waste."

For more on what makes good photography and how to produce it, he offers Notes and Tips from the field on some photos he's taken for National Geographic over the years. A recent feature on light pollution called Our Vanishing Night, is full of stunning urban, rural and aerial shots by Richardson that explore our relationship with the night sky.

For more on what makes good photography and how to produce it, he offers Notes and Tips from the field on some photos he's taken for National Geographic over the years. A recent feature on light pollution called Our Vanishing Night, is full of stunning urban, rural and aerial shots by Richardson that explore our relationship with the night sky.

While on the topic of preserving agricultural diversity, some Long Now followers might be thinking of the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, a seedbank on an archipelago near the North Pole. (Long Now Executive Director Alexander Rose visited the site in 02011.) Indeed, it's been on Richardson's radar as well: he traveled to Svalbard in 02010 and documented some run-ins with the local 'wildlife' on his blog.

We're looking forward to seeing Jim Richardson's artwork and hearing stories of his travels for this lecture and we hope you'll join us. The talk is on Wednesday February 22nd at the Cowell Theater. You can reserve tickets, get directions and sign up for the podcast on the Seminar page.

Subscribe to the Seminars About Long-term Thinking podcast for more thought-provoking programs.

Stewart Brand's Blog

- Stewart Brand's profile

- 291 followers