Stewart Brand's Blog, page 46

December 9, 2014

Brian Eno and Danny Hillis: The Long Now, now — a Seminar Flashback

photos by Kelly Ida Scope

photos by Kelly Ida Scope

In January 02014 Brian Eno and Danny Hillis, co-founders of The Long Now Foundation, spoke about The Long Now, now in our Seminars About Long-term Thinking series. Long Now’s third co-founder, Stewart Brand, joined them onstage for the second part of the talk.

Leaving the planet, singing, religion, drugs, sex, and parenting are all touched on in their wide-ranging and humor-filled discussion. There’s much about the 10,000 Year Clock project, of course, including details about how The Clock’s chime generator will work. And, fittingly, they discuss the notion of art as conversation.

Video of the 12 most recent Seminars is free for all to view. The Long Now, now is a recent SALT talk, free for public viewing until Februray 02015. Listen to SALT audio free on our Seminar pages and via podcast. Long Now members can see all Seminar videos in HD.

From Stewart Brand’s summary of the talk (in full here):

Hillis talked about the long-term stories we live by and how our expectations of the future shape the future, such as our hopes about space travel. Eno said that Mars is too difficult to live on, so what’s the point, and Hillis said, “That’s short-term thinking. There are three big game-changers going on: globalization, computers, and synthetic biology. (If I were a grad student now, I wouldn’t study computer science, I’d study synthetic biology.) I probably wouldn’t want to live on Mars in this body, but I could imagine adapting myself so I would want to live on Mars. To me it’s pretty inevitable that Earth is just our starting point.”

Danny Hillis is an inventor, scientist, author, and engineer. He pioneered the concept of parallel computers that is now the basis for most supercomputers, as well as the RAID disk array technology used to store large databases. He holds over 100 U.S. patents, covering parallel computers, disk arrays, forgery prevention methods, and various electronic and mechanical devices. Danny Hillis is also the designer of Long Now’s 10,000-year Clock.

Brian Eno is a composer, producer and visual artist. He was a founding member of Roxy Music and has produced albums for such groundbreaking artists as David Bowie, The Talking Heads and U2. He is credited with coining the term “Ambient Music” and making some of the definitive recordings in that genre. In recent years he has focused on generative art including numerous gallery installations and his Ambient Painting at The Interval at Long Now. His music is available for purchase at Enoshop.

The Seminars About Long-term Thinking series began in 02003 and is presented each month live in San Francisco. It is curated and hosted by Long Now’s President Stewart Brand. Seminar audio is available to all via podcast.

Everyone can watch full video of the last 12 Long Now Seminars (including this Seminar video until February 02015). Long Now members can watch the full ten years of Seminars in HD. Membership levels start at $8/month and include lots of benefits.

photos by Kelly Ida Scope

December 8, 2014

The Artangel Longplayer Letters: Carne Ross writes to John Burnside

In April, Long Now board member Esther Dyson wrote a letter to Carne Ross as part of the Artangel Longplayer Letters series. The series is a relay-style correspondence: The first letter was written by Brian Eno to Nassim Taleb. Nassim Taleb then wrote to Stewart Brand, and Stewart wrote to Esther Dyson, who wrote to Carne Ross. Carne’s response is now addressed to John Burnside, a novelist, short story writer and poet, who will respond with a letter to a recipient of his choosing.

In April, Long Now board member Esther Dyson wrote a letter to Carne Ross as part of the Artangel Longplayer Letters series. The series is a relay-style correspondence: The first letter was written by Brian Eno to Nassim Taleb. Nassim Taleb then wrote to Stewart Brand, and Stewart wrote to Esther Dyson, who wrote to Carne Ross. Carne’s response is now addressed to John Burnside, a novelist, short story writer and poet, who will respond with a letter to a recipient of his choosing.

The discussion thus far has focused on the extent and ways government and technology can foster long-term thinking. You can find the previous correspondences here.

From: Carne Ross, New York City

To: John Burnside, Berlin

8 December 2014

Dear John,

We are bidden to consider the future. What a privilege to be asked! What a nightmare to contemplate!

Esther Dyson wrote to me to propose an appealing scheme of how to inspire communities to be healthier. She spoke too of how data and technology, on which she is more than expert, enable government to provide better services and be accountable to citizens.

Of course she is right on this point, but I think you and I would want to take it some way further. Esther’s model is the familiar archetype of representative democracy, where the many elect the few to provide services for them. It is a transactional model, technocratic, with success or failure assessed with measurement and metrics. What’s missing are some essential questions: Who is doing what to whom? Who has power and who does not? Indeed, what is it all for? Like Esther, I want better and more accountable services for everyone. But this is not enough. The contemporary architecture of representative democracy and a capitalist economy, within which these reforms would take place, is to me, and I suspect you, deeply inadequate. Its flaws – inequality, environmental destruction, to name but two – are all too evident.

Let us look to the future, which is the challenge posed by this series of letters. I tried to cast my mind ten thousand years hence, or a thousand. Of course it was impossible. I could imagine space colonies and eternally-pickled brains whose contents are stored in data clouds. But what’s the use of such piddling fantasies? It seemed more worthwhile to fantasize about an ideal. How would humans live in an ideal world? I did not imagine a blueprint of such a world: if the twentieth century has taught us anything, it must be that utopian designs are inherently despotic; whether communist, fascist or even neo-liberal. Humans are forced to fit the design, and not the other way around. I tried to imagine how a human would ideally live, a thought experiment which proved one thing: how pathetically distant our current “civilisation” is from ideal. But the vision thereby also provided a kind of target.

How should humans ideally live? They would be fed and housed in as much comfort as they wished. They would live as long as they wanted in beauty and perfect, athletic health (you and I, I fear, are some way from this ideal already). They would be free to die as they choose, for eternal life would, I suspect, be its own kind of hell (though I would be willing to give it a go). They would live in peace, without hatred or resentment. They would wallow in mutual love with other humans (perhaps they could enjoy the permanent sensation of being “in love”). I have long doubted the idea of living in “harmony” with heartless, brutal nature, but humans in this ideal conception would enjoy their planet, unthreatened by its depredations, and reaping from it all that they needed They would be free of all coercion: no one would have power over anyone else. There would therefore be no government.

Their material needs and desires thus satisfied, humans would be free to indulge in what for me is the ultimate “point”, if there can be said to be such a thing, which would be the expression and enactment of all that is sublime and joyous of the immaterial: art, music, poetry (yes, John, you have a place there), love, sex (needless to say), pleasure, literature, voluptuous languor. There are not sufficient words for this fabulous realm; there is certainly no measure, which is why I recoil at our current obsession with metrics and measurable targets, and data: the things that matter most have no measure! It is there to be endlessly explored, imagined. It is the infinite.

Writing this today, I feel terribly sad and a little bit desperate. My expectation is that this ideal is, in reality, wholly unattainable. Looking forward once more, I fear that much more likely is that within a few hundred years, if not less, humanity will have successfully annihilated itself in ways already all too clear. Nuclear weapons cannot be dis-invented. It seems implausible to expect that the bombs will never be detonated. We have already come very close to nuclear war on several occasions in the few decades since their invention. The supposedly stable framework of strategic theory – “mutually assured destruction”, deterrence etc. – seems flimsy at best, likewise, is the reliance on lots of buttons that must be pressed, or keys that must be turned simultaneously, as launch devices designed to prevent an accidental launch. Most worryingly, the proliferation of these ghastly weapons has already put them in the trembling hands of nutters like the Kim family tyranny of North Korea, and under the control of governments which could tomorrow by overthrown by, millenarian extremists, whether religious or secular.

Then there is “the environment” where credible scientific forecasts of global warming are already painting a future of planetary catastrophe. A thousand years hence? Even getting through a hundred without mass starvation, war and species loss seems unlikely at this rate. God, I feel like should stop writing, pour myself a Highland malt and lose myself in your fine poems. No, I feel obliged to continue.

What is to be done? Metrical improvement of government services doesn’t quite hit the mark, does it? I am not preaching revolution, for Hannah Arendt was right to say that revolution merely brings us back to where we started, usually, with much bloodshed and misery along the way. I don’t believe in violent overthrow or hostility. Together, we might just make it. Divided, we most definitely shall not.

I do believe that a cultural, political, and economic reformation is possible; a profound and magnificent reimagining of how we live and how we get by with one another. Humans survive together. Alone, we are nothing: life is not worth living. The most important question is not what we believe, where we’re from, what sex we are, or what kind of music, or food, or sexual partner we like. It is: how do we deal with Other People? Get this right, in the economy and in politics, and we might just make it.

If the ideal is humans who are comfortable, healthy, free from violence or coercion, then that is where we should start. This is not impossible even today. Put people first and central in politics and the economy. In ancient Athens, many citizens played an active part in deciding the city’s future. Today, “participatory” processes allow the mass – sometimes tens of thousands of citizens, men and women – to decide things like budget priorities. When all are included in these decisions, the resulting policies reflect all of their interests; they are more equitable. In comparison, supposedly “representative” democracies will inevitably create elites (the few elected by the many) who are inherently susceptible to the influence of – if not corruptible by – the most powerful, thereby exacerbating, rather than reducing, any existing power imbalance.

Inequality supercharges this problem. The rich are already powerful. The evidence clearly shows that “democratic” legislation reflects their interests (literally: interest on capital is taxed at a lower rate than earned income, so a wealthy hedge fund owner is taxed at a lower rate than his cleaner). As Thomas Piketty has so convincingly demonstrated, the rich are indeed getting richer, because, as he shows, the returns on capital are, in general, greater than the returns on labour. Not only are the rest not getting richer (at all), the poor are, astonishingly, actually getting poorer. We are living in the age of the globalized, mega-wealthy plutocrats who control vast sums of money, and thus vast numbers of people. They control politics, philanthropy, culture, and even ideas (the musings of a billionaire are deemed, in publications like The New York Times, much more worthy of publication than the musings of, say, a street sweeper).

Fixing democracy is only half the solution. We must also promote new forms of economic activity, where profits and agency are shared, not concentrated in the hands of a tiny few. Employee-owned cooperatives, whether a bakery or a bank, can be as successful as the egoist entrepreneur (an archetype that is much too celebrated in contemporary culture; every successful individual stands on the shoulders of many). This is not state control, or redistribution by taxation, which of course is a kind of coercion, something we wish to avoid. It is altering the form, and thus the outcome, of economic activity at source.If widely implemented, with good will, patience and perseverance (for nothing human is ever perfect), such methods may have rapid effect, especially since humans are now so thoroughly connected with one another, and ever more so. Changing the method is tantamount to changing the outcome because, as Gandhi stressed, the means are the end. Change the manner in which we interact with one another, how we govern ourselves, how we make things, how we flourish, and we change everything. We are no longer mere outputs of an ideological system, we are in control, at the centre, the point.

John, I know that you share these sentiments. The question now that I cannot answer is how do we foment this transformation. Stalin imposed Marx’s revolution, causing untold horrors. Our reformation must come by suasion, not coercion. It’s clear that the disillusionment with the current status quo is rampant. But it is a different matter to turn that negative into a positive impulsion to build new things, new companies, new forums for decisions. Expert craftsman of words that you are, I suspect you would also agree that words alone are not enough. Are we to be dragged under by our own cynicism? Or will hope come to our rescue?

My hope is succoured by the hundred tales I hear of people of similar mind taking their own course, building businesses, starting communities, tending to the vulnerable, sharing their labour, love and resources for goals far greater than mere money, for solidarity, for compassion, for mutual aid; they who celebrate the best of humanity, not the most selfish: a thousand paths in the same direction, towards lives that are lived fully, marching forward in step alongside other humans, respecting and loving them and in common purpose with them. These stories move me to the quick. There are legion. May they prevail.

Over to you, my friend,

Carne

Carne Ross founded the world’s first not-for-profit diplomatic advisory group, Independent Diplomat. He writes on world affairs and the history of anarchism, recently publishing The Leaderless Revolution (2011), which looks into how, even in democratic nations, citizens feel a lack of agency and governments seem increasingly unable to tackle global issues.

John Burnside is a novelist, short story writer and poet. His poetry collection, Black Cat Bone, won both the Forward and the T.S. Eliot Prizes in 2011, a year in which he also received the Petrarch Prize for Poetry. He has twice won the Saltire Scottish Book of the Year award, (in 2006 and 2013). His memoir A Lie About My Father won the Madeleine Zepter Prize (France) and a CORINE Belletristikpreis des ZEIT Verlags Prize (Germany); his story collection, Something Like Happy, received the 2014 Edge Hill Prize. His work has been translated into French, German, Spanish, Italian, Turkish and Chinese. He writes a monthly nature column for The New Statesman and is a regular contributor to The London Review of Books.

December 2, 2014

Royal Ontario Museum Passenger Pigeons Now on Display at the Interval

Visitors to The Interval can now view two stunning passenger pigeon specimens on loan from the Royal Ontario Museum. The Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) houses the world’s largest collection of passenger pigeons. These specimens showcase the species’ unique male and female coloration and beauty.

The passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) once lived throughout eastern North America in enormous nomadic flocks – the largest flocks recorded in history. Fossil records date as far back as 240,000 years, yet in less than three decades the species went extinct in the wild due to commercial harvesting, leaving only a few birds in captivity by 01902. The last passenger pigeon died on September 1, 01914, at the Cincinnati Zoo.

Revive & Restore’s flagship project, The Great Passenger Pigeon Comeback, aims to use new genome editing tools to recreate passenger pigeons from their living relative, the band-tailed pigeon. Through a partnership with the UCSC Paleogenomics Laboratory, Revive & Restore is sequencing the genomes of Royal Ontario Museum specimens to provide the foundation for future flocks of passenger pigeons.

Revive & Restore gratefully acknowledges the Royal Ontario Museum for this generous temporary loan for visitors to enjoy. Revive & Restore’s Research and Science Consultant and lead scientist on The Great Passenger Pigeon Comeback, Ben Novak, will speak at the Royal Ontario Museum on September 26, 02014 for their De-Extinction Dialogues event. The title of his talk is “De-Extinction: a genetic future to the conservation legacy of the passenger pigeon.” Visit the ROM website for more details.

December 1, 2014

Kevin Kelly Seminar Media

This lecture was presented as part of The Long Now Foundation’s monthly Seminars About Long-term Thinking.

This lecture was presented as part of The Long Now Foundation’s monthly Seminars About Long-term Thinking.

Technium Unbound

Wednesday November 12, 02014 – San Francisco

Video is up on the Kelly Seminar page.

*********************

Audio is up on the Kelly Seminar page, or you can subscribe to our podcast.

*********************

Holos Rising – a summary by Stewart Brand

When Kevin Kelly looked up the definition of “superorganism” on Wikipedia, he found this: “A collection of agents which can act in concert to produce phenomena governed by the collective.” The source cited was Kevin Kelly, in his 01994 book, Out of Control. His 02014 perspective is that humanity has come to dwell in a superorganism of our own making on which our lives now depend.

The technological numbers keep powering up and connecting with each other. Their aggregate is becoming formidable, rich with emergent behavior, and yet it is still so new to us that it remains unnamed and scarcely considered.

Kelly clicked through some current tallies: one quintillion transistors; fifty-five trillion links; one hundred billion web clicks per day; one thousand communication satellites. Only a quarter of all the energy we use goes to humans; the rest drives Earth’s “very large machine.” Kelly calls it “the Technium” and spelled out what it is not. Not H.G. Wells’ “World Brain,” which was only a vision of what the Web now is. Not Teilhard de Chardin’s “Noosphere,” which was only humanity’s collective consciousness. Not “the Singularity,” which anticipates a technological event horizon that Kelly says will never occur as an event—”the Singularity will always be near.”

The Technium may best be considered a new organism with which we are symbiotic, as we are symbiotic with the aggregate of Earth’s life, sometimes called “Gaia.” There are pace differences, with Gaia slow, humanity faster, and the Technium really fast. They are not replacing each other but building on each other, and the meta-organism of their combining is so far nameless. Kelly shrugged, “Call it ‘Holos.’ Here are five frontiers I think that Holos implies for us…”

1) Big math of “zillionics” —beyond yotta (10 to the 24th) to, some say, “lotta” and “hella.” 2) New economics of the massive one-big-market, capable of surprise flash crashes and imperceptible tectonic shifts. 3) New biology of our superorganism with its own large phobias, compulsions, and oscillations. 4) New minds, which will emerge from a proliferation of auto-enhancing AI’s that augment rather than replace human intelligence. 5) New governance. One world government is inevitable. Some of it will be non-democratic—”I don’t get to vote who’s on the World Bank.“ To deal with planet-scale issues like geoengineering and climate change, “we will have to work through the recursive dilemma of who decides who decides?” We have no rules for cyberwar yet. We have no backup to the Internet yet, and it needs an immune system.

There is lots to work out, but lots to work it out with, and inventiveness abounds and converges. “We are,” Kelly said, “at just the beginning of the beginning.”

Subscribe to our Seminar email list for updates and summaries.

November 25, 2014

Software as Language, as Object, as Art

When The Long Now Foundation first began thinking about long-term archives, we drew inspiration from the Rosetta Stone, a 2000-year-old stele containing a Ptolemaic decree in Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics, Demotic script, and Ancient Greek. Our version of the Rosetta Stone, the Rosetta Disk, includes parallel texts in more than 1,500 languages. Since creating the Disk (a copy of which is now orbiting Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko on board the European Space Agency’s Rosetta probe), we have also partnered with the Internet Archive to create an online supplement that currently contains information on some 2,500 languages.

One of our purposes in creating The Rosetta Project was to encourage the preservation of endangered human languages. In a recent event at The Interval, The Future of Language, we explored the role these languages play in carrying important cultural information, and their correlation with biodiversity worldwide.

While we have focused our efforts on spoken languages and their written analogues, other organizations have begun preserving software—not just the end results, but the software itself. This is not only a way of archiving useful information and mitigating the risks of a digital dark age, but also a path to better understand the world we live in. As Paul Ford (a writer and programmer who digitized the full archive of Harper’s Magazine) wrote in The Great Works of Software, “The greatest works of software are not just code or programs, but social, expressive, human languages. They give us a shared set of norms and tools for expressing our ideas about words, or images, or software development.”

Matthew Kirschenbaum, the Associate Director of the Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities, made a similar point in the opening address of the Digital Preservation 2014 Meeting at the Library of Congress. In discussing George R. R. Martin’s idiosyncratic choice to write his blockbuster, doorstopper Song of Ice and Fire on an air-gapped machine running DOS and WordStar, Kirschenbaum notes that “WordStar is no toy or half-baked bit of code: on the contrary, it was a triumph of both software engineering and what we would nowadays call user-centered design.”

In its heyday, WordStar appealed to many writers because its central metaphor was that of the handwritten, not the typewritten, page. Robert J. Sawyer, whose novel Calculating God is a candidate for the Manual of Civilization, described the difference like this:

Consider: On a long-hand page, you can jump back and forth in your document with ease. You can put in bookmarks, either actual paper ones, or just fingers slipped into the middle of the manuscript stack. You can annotate the manuscript for yourself with comments like ‘Fix this!’ or ‘Don’t forget to check these facts’ without there being any possibility of you missing them when you next work on the document. And you can mark a block, either by circling it with your pen, or by physically cutting it out, without necessarily having to do anything with it right away. The entire document is your workspace.”

Screenshot of Wordstar Interface

If WordStar does offer a fundamentally different way of approaching digital text, then it’s reasonable to believe that authors using it may produce different work than they would with the mass-market behemoth, Microsoft Word, or one of the more modern, artisanal writing programs like Scrivener or Ulysses III, just as multi-lingual authors find that changing languages changes the way they think.

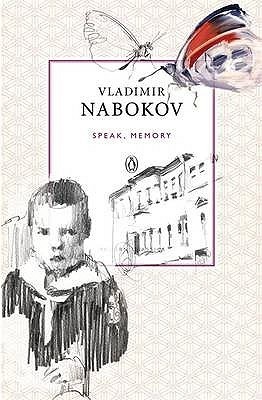

Samuel Beckett famously wrote certain plays in French, because he found that it made him choose his words more carefully and think more clearly; in the preface to Speak, Memory, Vladimir Nabokov said that the “re-Englishing of a Russian re-version of what had been an English re-telling of Russian memories in the first place, proved a diabolical task.” Knowing that A Game of Thrones was written in WordStar or that Waiting for Godot was originally titled “En Attendent Godot” may nuance our appreciation of the texts, but we can go even deeper into the relationship between software and the results it produces by examining its source code.

This was the motivation for the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum’s recent acquisition of the code for Planetary, a music player for iOS that envisions each artist in the music library as a sun orbited by album-planets, each of which is orbited in turn by a collection of song-moons. In explaining its decision to acquire not only a physical representation of the code, such as an iPad running the app, but the code itself, Cooper-Hewitt said,

With Planetary, we are hoping to preserve more than simply the vessel, more than an instantiation of software and hardware frozen at a moment in time: Commit message fd247e35de9138f0ac411ea0b261fab21936c6e6 authored in 2011 and an iPad2 to be specific.

Cooper-Hewitt’s Planetary announcement also touches on another challenge in archiving software.

[P]reserving large, complex and interdependent systems whose component pieces are often simply flirting with each other rather than holding hands is uncharted territory. Trying to preserve large, complex and interdependent systems whose only manifestation is conceptual—interaction design say or service design—is harder still.

One of the ways the Museum has chosen to meet this challenge is to open-source the software, inviting the public to examine the code, modify it, or build new applications on top of it.

The open-source approach has the advantage of introducing more people to a particular piece of software—people who may be able to port it to new systems, or simply maintain their own copies of it. As we have said in reference to the Rosetta Project, “One of the tenets of the project is that for information to last, people have to care about and engage it.” However, generations of software have already been lost, abandoned, or forgotten, like the software that controls the International Cometary Explorer. Other software has been preserved, but locked into black boxes like the National Software Reference Library at NIST, which includes some 20 million digital signatures, but is available only to law enforcement.

The International Cometary Explorer, a spacecraft we are no longer able to talk to

The International Cometary Explorer, a spacecraft we are no longer able to talk to

While there is no easy path to archiving software over the long term, the efforts of researchers like Kirschenbaum, projects like the Internet Archive’s Software Collection, and enthusiastic hackers like the Carnegie Mellon Computer Club, who recently recovered Andy Warhol’s digital artwork, are helping create awareness of the issues and develop potential solutions.

Original Warhol, created on a Amiga 1000 in 01985

Original Warhol, created on a Amiga 1000 in 01985

November 24, 2014

The Interval’s Chalk-Drawing Robot Makes Its Debut: December 8, 02014

On the evening of Monday December 8, 02014 from 8pm to midnight, come see the first demonstrations of Jürg Lehni’s Chalk-Drawing Machine at The Interval.

Jürg will be in attendance and will give live demonstrations throughout the evening.

The Long Now Foundation commissioned Jürg and his team in Switzerland to build a custom version of his Viktor chalk-drawing machine and create software to interface with it for our San Francisco bar/cafe/museum venue The Interval. We are working with Jürg to develop content for the machine and eventually make it a platform for use by visiting speakers and artists.

The design of the chalk-drawing machine is extremely elegant, using an unconventional system of pulleys that is driven by high-quality Maxon Swiss servo motors to triangulate the drawing tool. The motors are coordinated by an open-source controller developed by Jürg himself.

Thanks to swissnex San Francisco who brought Jürg Lehni and his work to San Francisco in 02013; we met Jürg through his participation in several shows that year.

November 20, 2014

Where Time Begins

Last year I had the opportunity to give a talk and tour of the US Naval Observatory in Washington DC at the invitation of Demetrios Matsakis, the director of the U.S. Naval Observatory’s Time Service department. The Naval Observatory hosts the largest collection of precise frequency standards in the world, and uses them to, among other things, keep services like internet time and the global positioning system in your phone running correctly.

The USNO Master Clock is actually an average of many timing signals

The USNO Master Clock is actually an average of many timing signals

The US Naval Observatory keeps track of time and distance in what seems like obscure ways, but these signals are used for some of the most widely trusted and life-critical systems on the planet. The observatory uses a series of atomic clocks, ranging from hydrogen mazers to cesium fountain clocks, which are averaged into the time signals we all use in synchronizing internet servers and finding our way with the guidance of our phones. In fact GPS would not be possible without the highly accurate time signals generated by the observatory, as time very literally equals distance when you are a satellite flying overhead at speeds that actually have to account for Einsteinian relativity.

The humble rack servers pumping out one of the most accurate and life-critical time signals in the world

The Naval Observatory is also part of the larger network in the US that includes NIST and several labs around the world that contribute to the international standards of time like Universal Coordinated Time or UTC. These time standards are defined in collaboration: many of the world’s national labs send in how long a second lasts based on their clocks, and these seconds are then averaged to define the second for the month. But ironically, they do this in retrospect and sometimes add leap seconds, so they only know what the ‘second’ was last month, not this month.

I am often asked when explaining the 10,000 Year Clock why we do not use an atomic clock, as they are often reported to be accurate to “one second in 30 million years”. But this does not mean they will last 30 million years; it is just a way to explain an accuracy of 10-9 seconds in everyday terms. These atomic clocks are extremely fragile and fussy machines that require very exact temperatures and deep understanding of atomic science in order to even read them. They sometimes only last a few years.

Two of the Cesium Fountain Clocks at the USNO used to create the master time signal

Two of the Cesium Fountain Clocks at the USNO used to create the master time signal

Demetrios was also able to tell me more about some of the long-term timing issues that affect The 10,000 Year Clock. Because the Clock synchronizes with the sun on any sunny day, one of the effects that we have to take into account is the rate at which the Earth’s rotational rate may change from millennium to millennium. It turns out that the earth’s rotation can be greatly affected by climate change. If the poles freeze in an ice age, and all the water freezes closer to the poles, the earth spins faster. If the current warming trend continues and the poles melt extensively, the mass of the water around the equator will slow the earth’s rotational rate. All these changes affect where the sun will appear in the sky, and since our clock uses the sun to synchronize, it is an effect we have to account for. While this was all known to us, there is a counter effect that Demetrios told me about. It turns out that when there is less water weighing down one of the tectonic plates of the earth, it rises up higher, counteracting some of the mass altered by the shift in water. We will be investigating this further to see if it changes our calculations.

Many thanks to Demetrios Matsakis for inviting me to the Naval Observatory, it was an honor to present to some of the most technical horologists in the world, and witness the place where the ephemerality of time is pinned down to just “one second in 30 million years”.

Kevin Kelly: Long-term Trends in the Scientific Method — Seminar Flashback

In March 02006 author and Long Now board member Kevin Kelly shared his thoughts on what awaits us in the next century of science. At the time Kevin was already at work on the book What Technology Wants which would be published 5 years later. If you enjoyed Kevin’s 02014 Seminar for Long Now “Technium Unbound“, then you’ll appreciate this talk as a precursor to his ideas about technology as a super-organism.

Long Now members can watch this video here. The audio is free for everyone on the Seminar page and via podcast. Long Now members can see all Seminar videos in HD. Video of the 12 most recent Seminars is also free for all to view.

From Stewart Brand’s summary of the talk (in full here):

Science, says Kevin Kelly, is the process of changing how we know things. It is the foundation our culture and society. While civilizations come and go, science grows steadily onward. It does this by watching itself. [...]

A particularly fruitful way to look at the history of science is to study how science itself has changed over time, with an eye to what that trajectory might suggest about the future.

Kevin Kelly is a former editor of the Whole Earth Review and Whole Earth Catalog. He was the founding Executive Editor at Wired magazine, and his other books include Out of Control and most recently Cool Tools: A Catalog of Possibilities (02013).

The Seminars About Long-term Thinking series began in 02003 and is presented each month live in San Francisco. It is curated and hosted by Long Now’s President Stewart Brand. Seminar audio is available to all via podcast.

Everyone can watch full video of the 12 most recent Long Now Seminars. Long Now members can watch video of this Seminar video or more than ten years of previous Seminars in HD. Membership levels start at $8/month and include lots of benefits.

November 19, 2014

Stewart Brand Keynote Video from 02014 Evernote Conference

On October 3rd 02014, Stewart Brand delivered the keynote address for the Evernote EC4 conference. Evernote is a service that allows people to collect information, notes, bookmarks, and create a personal searchable database with this collection.

Phil Libin, CEO of Evernote, has been a fan of Long Now for years, which inspired him to introduce a “100-year data guarantee” for all Evernote customers, a rare promise in the rapidly changing tech industry. The company is also known for having a long-term view and intends to be a “100-year startup”.

In the video above, Libin introduces Stewart while explaining how influential he and Long Now have been on Evernote’s philosophy. Stewart proceeds to give an update on our Revive & Restore project and the de-extinction of the Wooly Mammoth.

Evernote also gave out free copies of Stewart’s book The Clock of the Long Now: Time and Responsibility to attendees of EC4.

Stewart Brand founder The Well and Phil Libin founder Evernote discuss epochal change #EC2014 pic.twitter.com/9HN6FS9fI2

— Pat Egan (@eganpat) October 3, 2014

November 17, 2014

Kevin Kelly Seminar Media

This lecture was presented as part of The Long Now Foundation’s monthly Seminars About Long-term Thinking.

This lecture was presented as part of The Long Now Foundation’s monthly Seminars About Long-term Thinking.

Technium Unbound

Wednesday November 12, 02014 – San Francisco

Audio is up on the Kelly Seminar page, or you can subscribe to our podcast.

*********************

Holos Rising – a summary by Stewart Brand

When Kevin Kelly looked up the definition of “superorganism” on Wikipedia, he found this: “A collection of agents which can act in concert to produce phenomena governed by the collective.” The source cited was Kevin Kelly, in his 01994 book, Out of Control. His 02014 perspective is that humanity has come to dwell in a superorganism of our own making on which our lives now depend.

The technological numbers keep powering up and connecting with each other. Their aggregate is becoming formidable, rich with emergent behavior, and yet it is still so new to us that it remains unnamed and scarcely considered.

Kelly clicked through some current tallies: one quintillion transistors; fifty-five trillion links; one hundred billion web clicks per day; one thousand communication satellites. Only a quarter of all the energy we use goes to humans; the rest drives Earth’s “very large machine.” Kelly calls it “the Technium” and spelled out what it is not. Not H.G. Wells’ “World Brain,” which was only a vision of what the Web now is. Not Teilhard de Chardin’s “Noosphere,” which was only humanity’s collective consciousness. Not “the Singularity,” which anticipates a technological event horizon that Kelly says will never occur as an event—”the Singularity will always be near.”

The Technium may best be considered a new organism with which we are symbiotic, as we are symbiotic with the aggregate of Earth’s life, sometimes called “Gaia.” There are pace differences, with Gaia slow, humanity faster, and the Technium really fast. They are not replacing each other but building on each other, and the meta-organism of their combining is so far nameless. Kelly shrugged, “Call it ‘Holos.’ Here are five frontiers I think that Holos implies for us…”

1) Big math of “zillionics” —beyond yotta (10 to the 24th) to, some say, “lotta” and “hella.” 2) New economics of the massive one-big-market, capable of surprise flash crashes and imperceptible tectonic shifts. 3) New biology of our superorganism with its own large phobias, compulsions, and oscillations. 4) New minds, which will emerge from a proliferation of auto-enhancing AI’s that augment rather than replace human intelligence. 5) New governance. One world government is inevitable. Some of it will be non-democratic—”I don’t get to vote who’s on the World Bank.“ To deal with planet-scale issues like geoengineering and climate change, “we will have to work through the recursive dilemma of who decides who decides?” We have no rules for cyberwar yet. We have no backup to the Internet yet, and it needs an immune system.

There is lots to work out, but lots to work it out with, and inventiveness abounds and converges. “We are,” Kelly said, “at just the beginning of the beginning.”

Subscribe to our Seminar email list for updates and summaries.

Stewart Brand's Blog

- Stewart Brand's profile

- 291 followers