Stewart Brand's Blog, page 19

October 3, 2019

The History of China’s Cold Chain

Introducing wide-scale refrigeration to a nation’s food system brings about massive changes. Podcaster and journalist Nicola Twilley was able to witness those changes in real-time during a visit to China, where the amount of refrigerated space has grown more than 20x in the past ten years.

This highlight comes from Twilley’s 02018 talk at The Interval at Long Now, “Exploring the Artificial Cryosphere.” You can watch the full talk here.

September 30, 2019

How to Avoid a Negative Climate Future for the World’s Oceans

On September 25th, the UN-led Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released a landmark report on the impact of climate change on the world’s oceans. Over 100 authors from 36 countries analyzed the latest scientific findings on the cryosphere in a changing climate. The picture the report paints is dire, writes Robinson Meyer in The Atlantic:

While the report covers how climate change is reshaping the oceans and ice sheets, its deeper focus is how water, in all its forms, is closely tied to human flourishing. If our water-related problems are relatively easy to manage, then the problem of self-government is also easier. But if we keep spewing carbon pollution into the air, then the resulting planetary upheaval would constitute “a major strike against the human endeavor,” says Michael Oppenheimer, a lead author of the report and a professor of geosciences and international affairs at Princeton.

“We can adapt to this problem up to a point,” Oppenheimer told me. “But that point is determined by how strongly we mitigate greenhouse-gas emissions.”

If humanity manages to quickly lower its carbon pollution in the next few decades, then sea-level rise by 2100 may never exceed about one foot, the report says. This will be tough but manageable, Oppenheimer said. But if carbon pollution continues rising through the middle of the century, then sea-level rise by 2100 could exceed 2 feet 9 inches. Then “the job will be too big,” he said. “It will be an unmanageable problem.”

[…]

The headline finding of this report is that sea-level rise could be worse than we thought. The report’s projection of worst-case sea-level rise by 2100 is about 10 percent higher than the IPCC predicted five years ago. The IPCC has been steadily ratcheting up its sea-level-rise projections since its 2001 report, and it is likely to increase the numbers further in the 2021 report, when the IPCC runs a new round of global climate models.

The cascade of consequences related to sea-level rise include a decline in seafood safety, extreme flooding for coastal areas, a decline in biodiversity in the oceans, and the melting of glaciers in the United States, including ones major cities rely upon for water.

Unless policies are enacted to reduce carbon emissions now, many of the worst case scenarios outlined in the report might come to pass.

A new paper in Science details a “no-regrets to-do list” of ocean climate proposals that could be set in motion today. The proposals are based on another just-released report from the High Level Panel (HLP) for a Sustainable Ocean Economy that, the authors say, “provide hope and a path forward.”

The paper focuses on five areas of action mentioned in the report: renewable energy; shipping and transport; protection and restoration of coastal and marine ecosystems; fisheries, aquaculture, and shifting diets; and carbon storage in the seabed.

These five areas were identified, quantified, and evaluated relative to achieving the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The report concludes that these actions (in the right policy, investment, and technology environments) could reduce global GHG emissions by up to 4 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalents in 2030 and by up to 11 billion tonnes in 2050. This could contribute as much as 21% of the emission reduction required in 2050 to limit warming to 1.5°C and 25% for a 2°C target. Reductions of this magnitude are larger than the annual emissions from all current coal-fired power plants worldwide.

The paper offers short-term and long-term proposals around these five action areas, and include setting “clear national targets for increasing the share of ocean-based renewable energy”; improving the fuel efficiency of ships; restoring coastal “blue carbon” ecosystems; introducing seaweed to diets of sheep and cattle; encouraging diet shifts in humans to include more sources of sustainable low-carbon protein from the ocean,” and more.

“Make no mistake: These actions are ambitious,” the paper admits. “But we argue that they are necessary, could pay major dividends toward closing the emissions gap in coming decades, and achieve other co-benefits along the way.”

Another path forward was put forth earlier this summer by Revive & Restore. Its 200-page report provides the first-of-its-kind assessment of genomic and biotech innovations to complement, enhance, and accelerate today’s marine conservation strategies.

Revive & Restore’s mission is to enhance biodiversity through the genetic rescue of endangered and extinct species. In pursuit of this and in response to global threats to marine ecosystems, the organization conducted an Ocean Genomics Horizon Scan – interviewing almost 100 marine biologists, conservationists, and technologists representing over 60 institutions. Each was challenged to identify ways that rapid advances in genomics could be applied to address marine conservation needs. The resulting report is a first-of-its-kind assessment of highlighting the opportunities to bring genomic insight and biotechnology innovations to complement current and future marine conservation.

Our research has shown that we now have the opportunity to apply biotechnology tools to help solve some of the most intractable problems in ocean conservation resulting from: overfishing, invasive species, biodiversity loss, habitat destruction, and climate change. This report presents the most current genomic solutions to these threats and develops 10 “Big Ideas” – which, if funded, can help build transformative change and be catalytic for marine health.

Learn More

Watch Jeff Goodell’s Long Now talk, The Water Will Come.Read Revive & Restore’s Key Findings from its Ocean Genomics Horizon Scan.Read the IPCC’s press release on its latest report.

September 27, 2019

The Art of World-Building in Science Fiction

The process of world-building in science fiction isn’t just about coming to grips with the consequences of your narrative arc and making it believable. It’s also about imagining a better world.

Stanford anthropologist James Holland Jones spoke about “The Science of Climate Fiction: Can Stories Lead to Social Action?” in 02019 at The Interval. Watch his talk in full here.

September 21, 2019

How to Practice Long-term Thinking in a Distracted World

WIRED’s Editor-in-Chief Nicholas Thompson recently interviewed Bina Venkataraman about her new book, The Optimist’s Telescope: Thinking Ahead in a Reckless Age. Venkataraman’s book focuses on the need for more long-term thinking in the world, and explores issues that have long been a focus for us at Long Now, including the nuclear waste storage problem (discussed in the interview).

Nicholas Thompson: So what I want to do in this conversation with Bina is start out with some personal stuff, move to some organizational stuff, and then try to get to some complicated stuff. So let’s begin with the personal: Why did you write this?

Bina Venkataraman: Well, there’s two answers to that question. The first is that I think we are part of a generation of humanity who have never faced higher stakes for thinking ahead. We’re living longer than our grandparents or their grandparents, and we’re going to need to think about our own futures and how we plan for them. If you look at problems like climate change, our knowledge of how we impact the future is far greater than previous generations of humanity. But we are in a culture that’s encouraging instant gratification. And so I started to wonder: Is it actually possible to think ahead?

The personal part of the answer is that I was working in the White House, and part of my job was to meet with executives of major corporations—like food corporations, for example—and talk about the threat of drought and heat waves to their supply chain. So how farms are going to be affected, the potential for crop failure and a warming climate. One time I sat across from an executive, and he looked at me and said, “You know, I really care about this problem. I have children. I have grandchildren, but I just can’t think ahead. You know, my board and my shareholders have me focused on the quarter. I just can’t think ahead.”

September 16, 2019

Long Now hosts Anthropocene Film Festival

Phosphorus Mining

Phosphorus MiningLong Now is honored to host the San Francisco premiere of ANTHROPOCENE: The Human Epoch on Sunday, September 29, 02019 at 1:30pm at the historic Castro Theatre. This special Sunday afternoon Seminar will feature the film screening, followed by a Q&A with Stewart Brand and all 3 filmmakers.

A cinematic meditation on humanity’s massive reengineering of the planet, ANTHROPOCENE: The Human Epoch is a documentary film from Jennifer Baichwal, Nicholas de Pencier and Edward Burtynsky. The film follows the research of an international body of scientists, the Anthropocene Working Group, who after nearly 10 years of research, are arguing that the Holocene Epoch gave way to the Anthropocene Epoch in the mid-twentieth century, because of profound and lasting human changes to the Earth.

ANTHROPOCENE is the third and final full-length documentary film of the The Anthropocene Project, a multidisciplinary body of work combining fine art photography, film, virtual reality, augmented reality, scientific research and educational programs, seeks to investigate human influence on the state, dynamic, and future of the Earth.

Watermark and Manufactured Landscapes, the other 2 films in this Anthropocene trilogy, will show the same day at 5:30pm and 9:00pm at the Castro Theater, with separate tickets required for each screening. Tickets to see the 2 additional films need to be purchased in person at the theater box office (open from noon to 9:30pm) on the day of the event.

Tickets to the premiere of ANTHROPOCENE may be purchased here.

September 12, 2019

Short film of Comet 67P made from 400,000 Rosetta images is released

On August 6, 02014, the European Space Agency’s Rosetta probe successfully reached Comet 67P. In addition to studying the comet, Rosetta was able to place one of Long Now’s Rosetta Disks on its surface via its Philae lander.

In 02017, ESA released over 400,000 images from the Rosetta mission. Now, motion designer Christian Stangl has made a short film out of the images.

The Comet offers a remarkable, beautiful, and haunting look at this alien body from the Kuiper belt. Watch it below:

the Comet from Christian Stangl on Vimeo.

September 11, 2019

Long-term Building in Japan

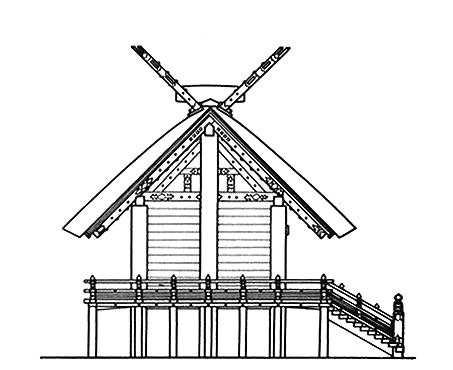

The Ise Shrine in Japan, which has been rebuilt every 20 years for over 1,400 years.

The Ise Shrine in Japan, which has been rebuilt every 20 years for over 1,400 years. When I started working with Stewart Brand over two decades ago, he told me about the ideas behind Long Now, and how we might build the seed for a very long-lived institution. One of the first examples he mentioned to me was Ise Shrine in Japan, which has been rebuilt every 20 years in adjacent sites for over 1,400 years. This shrine is made of ephemeral materials like wood and thatch, but its symbiotic relationship with the Shinto belief and craftsmen has kept a version of the temple standing since 692 CE. Over these past decades many of us at Long Now have conjured with these temples as an example of long-term thinking, but it had not occurred to me that I might some day visit them.

That is, until a few years ago, when I came across a news piece about the temples. It announced that the shrine’s foresters were harvesting the trees for the next rebuild, and I decided to do some research to find out how and when visitors could go see the one temple being replaced by the next. This research turned out to be very difficult, in part because of the language barrier, but also because the last rebuild took place well before the world wide web was anything close to ubiquitous. I kept my ear out and asked people who might know about the shrines, but did not get very far.

Then, one morning in late September, Danny Hillis called to tell me that Daniel Erasmus, a Long Now member in Holland, had learned that the shrine transfer ceremony would be taking place the following Saturday. Danny said he was going to try and meet Daniel in Ise, and wanted to know if he should document it. I told him he wouldn’t need to, because I was going to get on a plane and meet them there.

Ise Shrine

The next few days were a blur of difficult travel arrangements to a rural Japanese town where little English was spoken and lodging was already way over-booked. I was greatly aided by a colleague’s Japanese wife, who was able to find us a room in a traditional ryokan home-stay very close to the temples. I also put the word out about the trip, and Ping Fu from the Long Now Board decided to join us, as well.

Streets of Osaka.

Streets of Osaka.A few days later I met Ping at SFO for our flight to Osaka. Danny Hillis and Daniel Erasmus would be coming in from Tokyo a day later. We would stay the night in Osaka and then take the train to Ise. I found out that one of the other sites in Japan I had always wanted to visit was also close by: the Buddhist temples of Nara, considered to be some of the oldest continuously standing wooden structures in the world. We would be visiting Nara after our visit to Ise.

After landing, Ping and I spent a jet-lagged evening wandering around the Blade Runner streets of Osaka to find a restaurant. In Japan the best local food and drink are often tiny neighborhood affairs that only seat 5–10 people. Ping’s ability to read Kanji characters, which transfer over from Chinese, proved to be very helpful in at least figuring out if a sign was for a restaurant or a bathhouse.

“Fast food” in Osaka.

“Fast food” in Osaka.The next morning we headed east on a train to Ise eating “fast food” — morsels of fish and rice wrapped in beautiful origami of leaves. This was not one of the bullet trains; Ise is a small city whose economy has been largely driven by Shinto pilgrims for the last two millennia. A few decades before the birth of Christ, a Japanese princess is said to have spent over twenty years wandering Japan, looking for the perfect place to worship. Around year 4 of the current era she found Ise, where she heard the spirits whisper that this “is a secluded and pleasant land. In this land I wish to dwell.” And thus Ise was established as the Shinto spiritual center of Japan.

This is probably a good time to say a bit more about Shinto. While it is referred to often as a religion with priests and temples, there is actually a much deeper explanation, as with most things in Japan. Shinto is the indigenous belief system that goes back to at least 6 centuries BCE and pre-dates any religions in Japan — including Buddhism, which did not arrive until a millennium or so later. Shinto is an animist world view, which believes that spirits, or Kami, are a part of all things. It is said that nearly all Japanese are Shinto, even though many would self-describe as non-religious, or Buddhist. There are no doctrines or prophets in Shinto; people give reverence to various Kami for different reasons throughout their day, week, or life.

Shinto Priest at Ise gates.

Shinto Priest at Ise gates.There are over 80,000 Shinto temples, or Jinja, in Japan, and hundreds of thousands of Shinto “priests” who administer them. Of all of these temples, the structures at Ise, collectively referred to as Jingū, are considered the most important and the most highly revered. And of these, the Naikū shrine, which we were there to see, tops them all, and only members of the Japanese imperial family or the senior priests are allowed near or in the shrine. The simple yet stunningly beautiful Kofun-era architecture of the temples dates back over 2500 years, and the traditional construction methods have been refined to an unbelievably high art — even when compared to other Japanese craft.

Roof detail at shrine at Ise.

Roof detail at shrine at Ise.My understanding of how this twenty-year cycle became a tradition is that these shrines were originally used as seed banks. Since these were made of wood, they would need to be replaced and the seed stock transferred from one to the other. The design of the buildings and even the thatch roof are highly evolved for this. When there are rains, the thatch roof gets heavier, weighing down the wood joinery and making it water-tight. In the dry season, it gets lighter and the gaps between the wood are allowed to breathe again, avoiding mold.

The streets of Ise.

The streets of Ise.On Friday afternoon we arrived at Ise and, within a short walk, had checked in at our very basic ryokan hotel. The location was perfect, however, as we were directly across from the Naikū shrine area entrance. The town of Ise lies in a mainly flat lowland area across the bay from Nagoya (to the North). Its temples are the end destination of a pilgrimage route which people used to traverse largely by foot, and over the last 2,000 years various food and accommodation services have evolved to cater to those visitors.

Arriving at the temple area.

Arriving at the temple area.Ping and I wandered toward the entry and met up with Danny, Daniel, and Maholo Uchida, a friend of Daniel’s who is a curator at the National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation in Tokyo. Maholo would prove to be an absolutely amazing guide through the next 24 hours, and most of what I now understand about Ise and its customs comes from her.

Danny Hillis and Maholo Uchida purifying at the Temizuya.

Danny Hillis and Maholo Uchida purifying at the Temizuya.We traversed a small bridge and passed a low pool of water with a small roof over it. These Temizuya basins, found at the entry to all Shinto shrines, are a place to purify yourself before entry. As with all things in Japan — especially visits to shrines — there is an order and ceremony to washing your hands and mouth at the Temizuya. After this purification, we headed into the forest on a wide path of light grey gravel that crunched underfoot.

Just where the forest begins, we approached a large and beautifully crafted Shinto arch. These are apparently made from the timbers of an earlier shrine after it has been deconstructed. Visitors generally pass through three consecutive arches to enter a Shinto shrine area. Maholo quickly educated us on how to bow as we passed under the first arch (it is different for entering versus leaving) and on proper path walking etiquette. It is apparently too prideful to walk in the middle of the path: you should walk to one side, which is generally — but not always — the left side. As with everything here, there was etiquette to follow which was steeped in tradition and rules that would take a lifetime to understand fully.

Danny Hillis bowing under the first arch.

Danny Hillis bowing under the first arch.As we walked from arch to arch, Maholo explained that the forest here had historically been used exclusively to harvest timbers for all the shrines, but over the last millennia they had been harvested too heavily for various war efforts, or lost in fire. Since the beginning of this century the shrines’ caretakers have been bringing these forests back, and expect them to be self-sustaining again within the next two or three rebuilding periods — 40 to 60 years from now.

Third arch approaching the grand shrine.

Third arch approaching the grand shrine.Passing through a sequence of arches, we arrived at the Naikū shrine sanctuary area. This area includes a place that sells commemorative gifts. At this point you might be thinking “tourist trap gift shop,” but this adjacent structure is at least centuries old and of course perfectly fits the aesthetic. Instead of cheap plastic trinkets and coffee mugs, it offered hand-screened prints on wood from the last temple deconstruction, as well as calligraphic stamps for your shrine ‘passport’.

The 2,000 year-old gift shop.

The 2,000 year-old gift shop.Adjacent to the gift shop is the walled-off section of the Naikū shrine. Visitors are allowed to approach one spot, where there is a gap in the wall, and see a glimpse of the main temples. On the left, the one completed in 01993 has begun to grey (pictured below), and on the right gleams the newly finished temple, a dual view only seen once every 20 years. After this event, they will begin disassembly of the old shrine, and will leave just a little doghouse-sized structure in its place for the next two decades.

The old shrine, grey with age.

The old shrine, grey with age.The audience for this event consisted of only a few hundred people. Maholo explained that this rebuilding has been going on for eight years, and that many people come for different parts of the process, including the harvesting of the trees, the blessing of the tools, the milling of the timbers, the placement of the white river foundation stones, and so on.

As we stood there, crowds were gathering, and we noticed behind us a series of chests that were roped off in the courtyard area. Some of these were plain wood and some of them were lacquered. These chests contained the temple “treasures” that are moved from the old temple to the new. Some are re-created every 20 years by the greatest craftspeople in Japan, some have been moved from temple to temple for 14 centuries, and some are totally secret to all but the priests. The treasures are what the Kami spirits follow from one temple to the next as they are rebuilt. So the Shinto priests move the treasures when the new temple is ready, and the Kami spirits move sometime in the night to follow them in to their new home.

Treasure change ceremony at Ise.

Treasure change ceremony at Ise.As we took photos, a large group of priests and press started lining up. We were ushered over to the gift building area and held back by white gloved security personnel. It was a bit comical as they did not seem to know exactly what to do with us. Since this ceremony happens only every 20 years, it is unlikely that any of the staff were present at the last occasion: while this is one of the oldest events in the world, it is simultaneously brand new. It was very apparent that none of the ritual acts were performed for the audience. All of this ceremony was designed for the benefit of the Kami spirits, not for people’s entertainment, and much of what we saw were glimpses through trees from a distance. While it was hard to see everything, we all agreed that this perspective made the tradition much more magical and interesting than if it had all been laid bare.

Without fanfare, the princess of Japan led a march of hundreds of Ise priests down the path that we had just walked, and they all lined up in rows next to the chests. After a ceremony with nearly 30 minutes of bowing, the chests were carried into the sanctuary and placed into the new shrine (though this was out of view).

Then they came back out, lined up again, and went through a series of wave like bows before being led away by the princess.

All very calm, very simple, and without any hurrah. The Kami would soon follow the treasures into their new home.

What was a real surprise was to learn that there are 125 shrines in Ise: all are rebuilt every 20 years, but on different schedules. This is also done at other Shinto shrine sites, but not always every 20 years; some have cycles as long as 60 years. Once we were allowed to wander around again, we hiked up the hill to some of the other temples, all built for different Kami. Some recently-built shrines stood next to the ones awaiting deconstruction, and some stood alone. These are all made with similar design and unerring construction, and unlike the main temple, we were allowed to walk right up to these and take pictures.

A recently-built shrine stands next to an old one.

A recently-built shrine stands next to an old one.We left the forest on a different path as the sun set, bowing our exit bows twice after each of the three arches. We wandered through the town a bit and I suggested we find a local bar that offered the traditional Japanese “bottle keep” so we could drink half of a bottle and leave it on the shelf to return in 20 years for the other half.

Hopefully we’ll drink from this bottle again in 02033.

Hopefully we’ll drink from this bottle again in 02033.Maholo took us to a tiny alley where she peeked into a few shoji screens, eventually finding us the right place. It had only eight or so seats, and the proprietor was a lovely Japanes grandmother. We ordered a bottle of Suntory whiskey and began to pour.

The barkeep was amazed to find out how far we had traveled to see the ceremony, and put our dated Long Now bottle on the highest shelf in a place of honor.

Afterwards, Maholo had arranged for us to have dinner at a beautiful ryokan with one of the Shinto priests, who had come in from Tokyo to help with the events in Ise. We were served course after course of incredible seafood while he gracefully answered our questions, all translated by Maholo.

We learned that the priests who run Ise are their own special group within the Shinto organization, and don’t really follow the line of the main organization. For instance, when several of the Shinto temples were offered UNESCO world heritage site status, they politely declined. I can just imagine them wondering why they would need an organization like UNESCO, that is not even half a century old, to tell them that they had achieved “historic” status. I suspect that maybe in a millennium or two, if UNESCO is still around, they might reconsider.

The priests bringing the Kami their first meal.

The priests bringing the Kami their first meal.The next morning we returned to Naikū to catch a glimpse through the trees of the priests bringing the Kami their first meal. The Kami are fed in the morning and evening of each day from a kitchen building behind the temple sanctuary. We watched priests and their assistants bringing in chests of food as we chatted with an American who works for the Shinto central office in Tokyo. He had put together a beautiful book about the shrines at Ise, The Soul of Japan, to which he later sent me a link to share in this report.

Afterwards, we also visited the small but amazing museum at Ise that displays some of the “treasures” from past shrines, a temple simulacrum, and a display documenting the 1400-year reconstruction history along with the beautiful Japanese tools used for building the shrines.

Bridge to the Gekū shrines.

Bridge to the Gekū shrines.Then Maholo took us to the Gekū shrine areas, a few kilometers away, which allow much more access. These shrines, and the bridge that leads to them, are also built on the alternating-site, 20-year cycle. But here you walk on the right, and there are four arches — I could not find out why. Most interesting, however, is that in World War II the Japanese emperor ordered a rare temporary delay in shrine rebuilding. While the people of Ise could not defy him, they realized that he had only mentioned the shrines, so they went ahead and rebuilt the bridge as scheduled in the middle of a war-torn year.

Finally, we headed to the train station, from where Danny and Daniel would travel to Kyoto for their flights, and Maholo would return to Tokyo. Ping and I later boarded the train to Osaka to stay the night, and then headed to Nara prefecture the next day.

Entering Hōryū-ji

Entering Hōryū-jiHōryū-ji at Nara

Only 45 minutes by train from Osaka is the stop at Hōryū-ji, a bit before you get to Nara center. Almost concurrent to the building of the first shrine at Ise in the 7th century, a complex of Buddhist temples were built here beginning in 607 CE.

The tall pagoda at Hōryū-ji is one of the oldest continuously standing structures in the world. And while there is controversy over which parts of this temple complex are orginal, the central vertical pillar of wood in the Pagoda was definitively felled in 594.

The architecture has a strong Chinese influence, reflecting the route Buddhism traveled before arriving in Japan, and came with a tradition of continual maintenance rather than periodic rebuilding.

Roof detail at Hōryū-ji

Roof detail at Hōryū-jiI suspect one of the main reasons these buildings have survived so long is their ceramic roof. The roof tiles can last centuries and are vastly less susceptible to fire than wood or thatch. Like the Shinto shrines, though, no one resides in these buildings, so the chance of human error starting a blaze is vastly diminished. I was amused to see the “no smoking” sign as we entered one of temples.

No smoking sign at Hōryū-ji

No smoking sign at Hōryū-jiAs you walk through these temples there are many beautiful little maintenance details. Places where water would have wicked into the bottom of a pillar or around the edge of a metal detail have been carefully removed, with new wood spliced back in over the centuries.

It is striking that this part of Japan houses two sets of structures, both of nearly equal age, and both made of largely ephemeral materials that have lasted over 14 centuries through totally different mechanisms and religions. Both require a continuous, diligent and respectful civilization to sustain them, yet one is punctuated and episodic, while the other is gradual. Both are great models for how to make a building, or an institution, last through millennia.

Learn More

Read Alexander Rose’s recent essay in BBC Future, “How to Build Something that Lasts 10,000 Years.”See more photos from Alexander Rose’s trip to Japan here.Read Soul of Japan: An Introduction to Shinto and Ise Jingu (02013) in full here.

September 5, 2019

What a Prehistoric Monument Reveals about the Value of Maintenance

Members of Long Now London chalking the White Horse of Uffington, a 3000-year-old prehistoric hill figure in England. Photo by Peter Landers.

Members of Long Now London chalking the White Horse of Uffington, a 3000-year-old prehistoric hill figure in England. Photo by Peter Landers.Imagine, if you will, that you could travel back in time three thousand years to the late Bronze Age, with a bird’s eye view of a hill near the present-day village of Uffington, in Oxfordshire, England. From that vantage, you’d see the unmistakable outlines of a white horse etched into the hillside. It is enormous — roughly the size of a football field — and visible from 20 miles away.

Now, fast forward. Bounding through the millennia, you’d see groups of people arrive from nearby villages at regular intervals, making their way up the hill to partake in good old fashioned maintenance. Using hammers and buckets of chalk, they scour the hillside to ensure the giant pictogram is not obscured. Without this regular maintenance, the hill figure would not last more than twenty years before becoming entirely eroded and overgrown. After the work is done, a festival is held.

Entire civilizations rise and fall. The White Horse of Uffington remains. Scribes and historians make occasional note of the hill figure, such as in the Welsh Red Book of Hergest in 01382 (“Near to the town of Abinton there is a mountain with a figure of a stallion upon it, and it is white. Nothing grows upon it.”) or by the Oxford archivist Francis Wise in 01736 (“The ceremony of scouring the Horse, from time immemorial, has been solemnized by a numerous concourse of people from all the villages roundabout.”). Easily recognizable by air, the horse is temporarily hidden by turf during World War II to confuse Luftwaffe pilots during bombing raids. Today, the National Trust preserves the site, overseeing a regular act of maintenance 3,000 years in the making.

Long Now London chalking the White Horse. Photo by Peter Landers.

Long Now London chalking the White Horse. Photo by Peter Landers.Earlier this summer, members of Long Now London took a field trip to Uffington to participate in the time-honored ceremony. Christopher Daniel, the lead organizer of Long Now London, says the idea to chalk the White Horse came from a conversation with Sarah Davis of Longplayer about the maintenance of art, places and meaning across generations and millennia.

“Sitting there, performing the same task as people in 01819, 00819 and around 800 BCE, it is hard not to consider the types and quantities of meaning and ceremony that may have been attached to those actions in those times,” Daniel says.

The White Horse of Uffington in 01937. Photo by Paul Nash.

The White Horse of Uffington in 01937. Photo by Paul Nash.Researchers still do not know why the horse was made. Archaeologist David Miles, who was able to date the horse to the late Bronze Age using a technique called optical stimulated luminescence, told The Smithsonian that the figure of the horse might be related to early Celtic art, where horses are depicted pulling the chariot of the sun across the sky. From the bottom of the Uffington hill, the sun appears to rise behind the horse.

“From the start the horse would have required regular upkeep to stay visible,” Emily Cleaver writes in The Smithsonian. “It might seem strange that the horse’s creators chose such an unstable form for their monument, but archaeologists believe this could have been intentional. A chalk hill figure requires a social group to maintain it, and it could be that today’s cleaning is an echo of an early ritual gathering that was part of the horse’s original function.”

In her lecture at Long Now earlier this summer, Monica L. Smith, an archaeologist at UCLA, highlighted the importance of ritual sites like Stonehenge and Göbekli Tepe in the eventual formation of cities.

“The first move towards getting people into larger and larger groups was probably something that was a ritual impetus,” she said. “The idea of coming together and gathering with a bunch of strangers was something that is evident in the earliest physical ritual structures that we have in the world today.”

Photo by Peter Landers.

Photo by Peter Landers.For Christopher Daniel, the visit to Uffington underscored that there are different approaches to making things last. “The White Horse requires rather more regular maintenance than somewhere like Stonehenge,” he said. “But thankfully the required techniques and materials are smaller, simpler and much closer to hand.”

Though it requires considerably less resources to maintain, and is more symbolic than functional, the Uffington White Horse nonetheless offers a lesson in maintaining the infrastructure of cities today. “As humans, we are historically biased against maintenance,” Smith said in her Long Now lecture. “And yet that is exactly what infrastructure needs.”

The Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco. Photo by Rich Niewiroski Jr.

The Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco. Photo by Rich Niewiroski Jr.When infrastructure becomes symbolic to a built environment, it is more likely to be maintained. Smith gave the example of San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge to illustrate this point. Much like the White Horse, the Golden Gate Bridge undergoes a willing and regular form of maintenance. “Somewhere between five to ten thousand gallons of paint a year, and thirty painters, are dedicated to keeping the Golden Gate Bridge golden,” Smith said.

Photos by Peter Landers.

Photos by Peter Landers.For members of Long Now London, chalking the White Horse revealed that participating in acts of maintenance can be deeply meaningful. “It felt at once both quite ordinary and utterly sublime,” Daniel said. “The physical activity itself is in many ways straightforward. It is the context and history that elevate those actions into what we found to be a profound experience. It was also interesting to realize that on some level it does not matter why we do this. What matters most is that it is done.”

Daniel hopes Long Now London will carry out this “secular pilgrimage” every year.

“Many of the oldest protected routes across Europe are routes of pilgrimage,” he says. “They were stamped out over centuries by people carrying or searching for meaning. I want the horse chalking to carry meaning across both time and space. If even just a few of us go to the horse each year with this intent, it becomes a tradition. Once something becomes a tradition, it attracts meaning, year by year, generation by generation. On this first visit to the horse, one member brought his kids. A couple of other members said they want to bring theirs in the future. This relatively simple act becomes something we do together—something we remember as much for the communal spirit as for the activity itself. In so doing, we layer new meaning onto old as we bash new chalk into old.”

Learn More

Read more about the White Horse of Uffington in Emily Cleaver’s article for The Smithsonian.Watch Monica L. Smith’s Long Now Seminar, “Cities: The First 6,000 Years.”Long Now London meets on the second Thursday of every month. Its next gathering is at the Royal Society of Arts on Thursday, September 12th at 6pm. They will be screening Benjamin Grant’s recent Long Now Seminar, “Overview: Earth and Civilization in the Macroscope.” More info can be found here.Those interested in Long Now London can email hi@longnowlondon.org or follow them on Twitter and Instagram.

September 1, 2019

The Amazon is not the Earth’s Lungs

An aerial view of forest fire of the Amazon taken with a drone is seen from an Indigenous territory in the state of Mato Grosso, in Brazil, August 23, 2019, obtained by Reuters on August 25, 2019. Marizilda Cruppe/Amnesty International/Handout via REUTERS.

An aerial view of forest fire of the Amazon taken with a drone is seen from an Indigenous territory in the state of Mato Grosso, in Brazil, August 23, 2019, obtained by Reuters on August 25, 2019. Marizilda Cruppe/Amnesty International/Handout via REUTERS.In the wake of the troubling reports about fires in Brazil’s Amazon rainforest, much misinformation spread across social media. On Facebook posts and news reports, the Amazon was described as being the “lungs of the Earth.” Peter Brannen, writing in The Atlantic, details why that isn’t the case—not to downplay the impact of the fires, but to educate audiences on how the various systems of our planet interact:

The Amazon is a vast, ineffable, vital, living wonder. It does not, however, supply the planet with 20 percent of its oxygen.

As the biochemist Nick Lane wrote in his 2003 book Oxygen, “Even the most foolhardy destruction of world forests could hardly dint our oxygen supply, though in other respects such short-sighted idiocy is an unspeakable tragedy.”

The Amazon produces about 6 percent of the oxygen currently being made by photosynthetic organisms alive on the planet today. But surprisingly, this is not where most of our oxygen comes from. In fact, from a broader Earth-system perspective, in which the biosphere not only creates but also consumes free oxygen, the Amazon’s contribution to our planet’s unusual abundance of the stuff is more or less zero. This is not a pedantic detail. Geology provides a strange picture of how the world works that helps illuminate just how bizarre and unprecedented the ongoing human experiment on the planet really is. Contrary to almost every popular account, Earth maintains an unusual surfeit of free oxygen—an incredibly reactive gas that does not want to be in the atmosphere—largely due not to living, breathing trees, but to the existence, underground, of fossil fuels.

Read Brannen’s piece in full here.

August 28, 2019

The Vineyard Gazette on Revive & Restore’s Heath Hen De-extinction Efforts

The world’s last heath hen went extinct in Martha’s Vineyard in 01932. The Revive & Restore team recently paid a visit there to discuss their efforts to bring the species back.

Members of the Revive & Restore team next to a statue of Booming Ben, the last heath hen.

Members of the Revive & Restore team next to a statue of Booming Ben, the last heath hen.From the Vineyard Gazette:

Buried deep within the woods of the Manuel Correllus State Forest is a statue of Booming Ben, the world’s final heath hen. Once common all along the eastern seaboard, the species was hunted to near-extinction in the 1870s. Although a small number of the birds found refuge on Martha’s Vineyard, they officially disappeared in 1932 — with Booming Ben, the last of their kind, calling for female mates who were no longer there to hear him.

“There is no survivor, there is no future, there is no life to be recreated in this form again,” Gazette editor Henry Beetle Hough wrote. “We are looking upon the uttermost finality which can be written, glimpsing the darkness which will not know another ray of light. We are in touch with the reality of extinction.”

The statue memorializes that reality.

Since 2013, however, a group of cutting-edge researchers with the group Revive and Restore have been hard at work to bring back the heath hen as part of an ambitious avian de-extinction project. The project got started when Ryan Phelan, who co-founded Revive and Restore with her husband, scientist and publisher of the Whole Earth Catalogue, Stewart Brand, began to think broadly about the goals for their organization.

“We started by saying what’s the most wild idea possible?” Ms. Phelan said. “What’s the most audacious? That would be bringing back an extinct species.”

Read the piece in full here.

Stewart Brand's Blog

- Stewart Brand's profile

- 291 followers