Stewart Brand's Blog, page 106

March 4, 2011

Human Language in the Palm of My Hand

Two days ago, we learned that a Rosetta Disk made its way into the Special Collections of the University of Colorado Boulder library, and was on public display there. One of our members, Zane Selvans paid a visit, and had an extraordinary experience. He took fantastic pictures and wrote it up on his blog Amateur Earthling – we repost it here with his permission. It is a great illustration of the challenge in keeping information alive over time, place, and people.

Human Language in the Palm of my Hand

by Zane Selvans

One of the Rosetta discs was recently bequeathed to the University of Colorado libraries, and the Long Now put out a request for pictures of it in its new home. I eagerly responded by heading to the special collections in Norlin yesterday. It didn't seem to be on display anywhere, so when the librarian made eye contact, I said I was here to see the Rosetta disc, and she sent someone off to get it. And they took it out of its Pelican case, and set it on the table in front of me (after I'd filled out a reader card and agreed only to take notes in pencil… or by digital means — no pens are allowed near the old books) At first I was hesitant to touch it, and asked if it was okay, and she said "Oh it doesn't look like the kind of thing that requires any special handling." So I picked it up.

I was amazed at the weight of the thing. The tungsten hemisphere (I think it's tungsten anyway… but maybe I'm thinking of one of the clock parts) [ed. note - it is actually stainless steel] is much denser than most everyday objects. That, plus the iridescent sheet of the etched words and the distortion of the lens makes it into a strange kind of artifact. It's obviously a weird thing. I couldn't help but think of Michael Madsen's Into Eternity, and the difficulty of attempting to ensure that we communicate anything tens of thousands of years into the future. His one way conversation with those who inherit our histories. These spheres are beautiful art and elegant thought experiments today, but holding one made me envision the world in which they were actually needed, where they've been used for their intended purpose. Far seeing, informational time machines. Linguistic Palantír. It's both horrifying and hopeful to think about what could come to pass in our deep futures.

If this thing has been used, then darkness fell one day.

If this thing has been used, then someone made it through, and they want to know again.

I couldn't help myself. I had to open it up. Gingerly. It's a hard thing to handle, so smooth and round and heavy enough that it's challenging to control it with one hand. The lockring tinkled down and the librarian looked over a little surprised. "Oh, I didn't know you could open it."

Have you looked at it. Do you know what it is? Something to do with languages. Mmm. Yes.

With only a single change of custody, all information about the thing had already apparently been lost. They said that when it was checked in to the collections, it hadn't come with any accompanying documentation. Just a strange heavy sphere in a padded box. The box was labeled, saying who it had come from, and naming it a Rosetta disc, but that was about it. It's supposed to be usable even without any documentation — that's kind of the point — but it certainly does highlight the fragility of information. I tweeted to the Long Now afterward, and they've sent "Care and Feeding" documentation to the curator. Somehow it feels good to have participated, even peripherally, in the smuggling of this information into the future.

March 3, 2011

'In Our Time' on the Nervous System

Mind Hacks points us to a great BBC Radio 4 program on the history of our knowledge of the nervous system:

It's a satisfyingly in-depth discussion that tracks first beliefs about the nervous system from ancient times through the renaissance into the modern age.

Check out the In Our Time episode page, or download the mp3.

March 2, 2011

A Rosetta Disk is on public display in the University of Colorado Boulder Libraries Special Collection

In 02008, one of the first prototype Rosetta Disks went to the family of the late Charles Butcher, who was the founder of The Lazy 8 Foundation. Lazy Eight was one of the first supporters of the Long Now 10,000 Year Library and Rosetta Projects.

This Rosetta Disk has now been donated by the Charles Butcher family to the University of Colorado Boulder. It looks like it is housed in the Library Special Collections, and that it is currently on exhibit as part of Realia: Everyday Objects from Other Lives.

If anyone has a chance to go visit the Rosetta Disk in this exhibit, please send us photos!

Lake Vostok

The sixth largest lake in the world is located deep in the continent of Antarctica where it has been isolated under two and a half miles of solid ice for more than 14 million years…and, according to the Wired Science blog, it will remain so for at least one year more. A team of Russian scientists that has been drilling through the ice was scheduled to break through this month, but extreme weather has required them to leave the site until next December. So what's in the water?

What lies beneath the mammoth sheet of ice may provide answers to what Earth was like before the Ice Age and how life has evolved.

Most importantly, Lake Vostok appears to be incredibly similar to the frozen lakes of Jupiter's Europa satellite and Saturn's Enceladus. As Wired UK reported earlier this week, NASA and the ESA have already planned a mission to esplora Europa's lake in 2020. If life is found in Vostok, the implications for the possibility of extraterrestrial life on Europa and Enceladus are huge.

"It's like exploring an alien planet where no one has been before," said Valery Lukin of the Arctic and Antarctic Research told Reuters. "We don't know what we'll find."

One thing that some people hope they don't find is kerosene (or Shoggoths, for that matter), the substance with which the team has filled their unfinished bore-hole to prevent it from icing over.

March 1, 2011

Peak Science?

Moons of Jupiter through an amateur telescope, photo by Thomas Bresson

Forgive the metaphor, but earlier this month in the Wall Street Journal, Jonah Lehrer discussed several trends that have emerged in scientific discovery over the past century that indicate we may need to start 'digging deeper.'

An economist at Northwestern named Benjamin Jones has pointed out the first of those trends by analyzing millions of published scientific papers. He found that the prevalence of teams working on papers has been growing steadily; there are more papers published these days that have several authors than in the past. That prevalence is especially pronounced among highly successful papers: those that receive a disproportionate amount of citations in other papers. So, using papers published as an indication of scientific progress seems to indicate that more work is being done collaboratively and that productive science seems to increasingly require more work and wider expertise than a single person can muster.

The second trend comes from Samuel Arbesman, a researcher at Harvard Medical School. He's found that across many different disciplines, the relative magnitude of discoveries seems to be falling:

By measuring the average size of discovered asteroids, mammalian species and chemical elements, he was able to show that, over the last few hundred years, these three very different scientific fields have been obeying the exact same trend: the size of what they discover has been getting smaller.

These trends seem to indicate that science is actually getting harder. Lehrer borrows a metaphor from Tyler Cowen's The Great Stagnation to argue that we've basically picked all the low-hanging fruit of scientific discovery – all Galileo had to do was be the first person to look at Jupiter through a telescope and he discovered four moons. But, we've found all the moons now, and without those easy to reach facts, we're now forced to pool more effort and resources into learning new things.

February 28, 2011

Long Now Media Update

WATCH

Mary Catherine Bateson's "Live Longer, Think Longer"

There is new media available from our monthly series, the Seminars About Long-term Thinking. Stewart Brand's summaries and audio downloads or podcasts of the talks are free to the public; Long Now members can view HD video of the Seminars and comment on them.

The Data Deluge

The figure shows the projected increase in global climate data holdings for climate models, remotely sensed data, and in situ.

On February 11 Science magazine published a special issue dedicated to the challenges that research communities face as they produce increasing quantities and types of data. One of the articles tells the story of particle physicist Siegfried Bethke, who wanted to reanalyze the data from an experiment conducted twenty years earlier. He discovered that no organized effort had been made to preserve the data, and it took him, his secretary and a graduate student two years to find it all and rewrite the now-obsolete code necessary to read it.

"The problem starts when the experiment is over, and the data used by one group of people is only understood by those people," [Cristinel] Diaconu says. "When they go off and do other things, the data is orphaned; it has no parents anymore." The orphan metaphor only goes so far: After a certain point, orphaned data can't be adopted by later researchers who weren't part of the original team. Even given the raw data, only someone intimately involved in the original experiment can make sense of it.

A particle physics study group has recommended that every large experiment hire a 'data archivist,' a sort of Receiver of Memory who would be responsible for making sure that data remains intelligible and accessible long after 'the end' of a project.

A data archivist would be a mix of librarian, IT expert, and physicist, with the computing skills to keep porting data to new formats but savvy enough about the physics to be able to crosscheck old results on new computer systems.

As indicated by another article in the special issue, "Climate Data Challenges in the 21st Century," scientists not only need to make their data accessible to colleagues and to researchers of the future, but also to non-researchers of the present. As managers and policy-makers move to address time-sensitive issues such as climate change, the long-term soundness of their decisions will depend at least partly on the information available to them.

Increased support from the funding agencies is needed to enhance data access, manipulation, and modeling tools; improve climate system understanding; articulate model limitations; and ensure that the observations necessary to underpin it all are made. Otherwise, climate science will suffer, and the climate information needed by society—climate assessment, services, and adaptation capability—will not only fall short of its potential to reduce the vulnerability of human and natural systems to climate variability and change, but will also cause society to miss out on opportunities that will inevitably arise in the face of changing conditions.

February 25, 2011

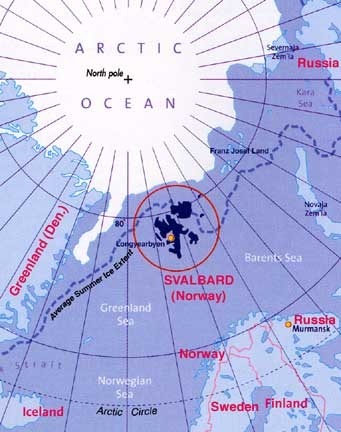

Svalbard Seed Vault

Alexander Rose (left) and Steve Rowell (right) at the Svalbard Seed Vault

Long Now Executive Director and Clock Project Manager Alexander Rose is currently in Longyearbyen Svalbard in the Spitsbergen archipelago with artist Steven Rowell. We are here to visit the 1000 year seed vault and talk with its engineers. We will hopefully be getting into the vault on Sunday (the entry part anyway, no one but a few scrubbed down and sterilized technicians are allowed in the actual vault). But today we drove up there and shot the image above between 40 mph wind and snow gusts. You can follow the trip updates live on twitter by following @zander.

Long Now Graffiti

We heard last week that some "Long Now Graffiti" showed up on the sidewalk out in front of the Pixar animation studios in Emeryville California. A friend just sent in pictures of it… I assume no one wants to come forward to tell us more about it, but I would really love to know why it only goes to the year 10,000. Why not 12011?

February 24, 2011

Matt Ridley Ticket Info

Seminars About Long-term Thinking

Matt Ridley on "Deep Optimism"

TICKETS

Tuesday March 22, 02011 at 7:30pm Novellus Theater at YBCA

Long Now Members can reserve 2 seats, join today! • General Tickets $10

About this Seminar:

Via trade and other cultural activities, "ideas have sex," and that drives human history in the direction of inconstant but accumulative improvement over time. The criers of havoc keep being proved wrong. A fundamental optimism about human affairs is deeply rational and can be reliably conjured with.

Trained at Oxford as a zoologist and an editor at The Economist for eight years, Matt Ridley's newest book is The Rational Optimist: How Prosperity Evolves. His earlier works include Francis Crick; Nature via Nurture; Genome; and The Origins of Virtue.

Long Now is presenting this Seminar in partnership with Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, whose commitment to providing a forum for the most compelling contemporary thought continues with this collaboration.

Twitter - up to the minute info on tickets and events

Long Now Blog – daily updates on events and ideas

Facebook – stay in touch through our fan page

Long Now Meetups - join one or start your own

Stewart Brand's Blog

- Stewart Brand's profile

- 291 followers