Doug Henwood's Blog, page 5

February 16, 2025

No, federal spending and employment are not “out of control”

Among the leading fantasies of the moment are that federal employment and spending are “out of control,” so drastic action is needed to put things back in order. These are lies. Some people who utter these lies probably know better and some don’t, but they’re still lies.

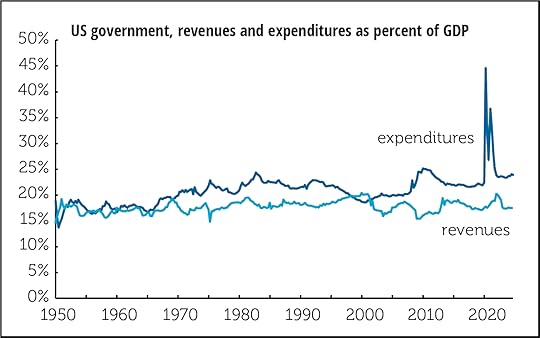

First, let’s look at federal expenditures and revenues as a percent of GDP. (These come from table 3.2 in the national income accounts, by the way.) People who want to deceive will often cite raw dollar amounts to amplify the gee-whiz factor, but the only honest way to render these quantities over time is by comparing them to total economic output. You could, if you had deceptive intentions, say, “Federal spending is up by $2.3 trillion over the last five years.” Which is true, but GDP is up by $7.8 trillion.

Aside from surges around recessions (mid-1970s, early 1980s, 2008–2010) and the covid pandemic, the expenditures line has been essentially flat for the last 40 years. A serious problem, if you’re concerned about debt and deficits—I’ll address that some other time—is that, aside from the late 1990s, revenues haven’t kept up with spending since around 1970. They took hits from George W. Bush’s tax cuts after 2001 and from Trump’s after 2017, but the revenue line has also been essentially flat for decades, just at a level well below spending. Funnily, the people most concerned about debts and deficits—rich people and those who shill for them—are the ones most opposed to paying taxes.

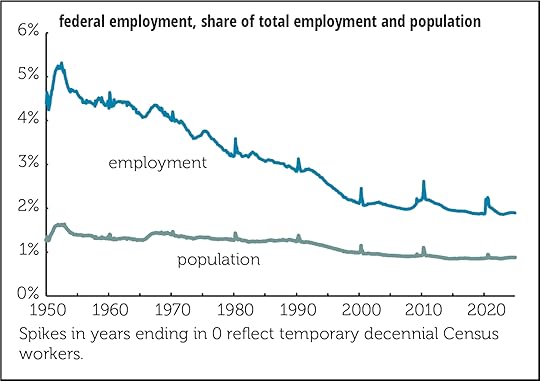

And now federal employment, graphed below as a share of total employment and the population.

Both are in downtrends. In 1950, back when America was Great, federal employment was 4.4% of total employment and 1.3% of the population. In 2024, it was 1.9% of employment and 0.9% of the population. Both are exactly the same as when Trump took office—there was no surge under Biden. Both are well below where they were when Reagan took office.

Not that this will have any effect on the Discourse . But hope dies last.

. But hope dies last.

February 13, 2025

Fresh audio product: untangling DEI, the history of “choice”

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

February 13, 2025 Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò picks apart the contradictory strands of the DEI obsession • Sophia Rosenfeld, author of The Age of Choice, explores this history of that concept over the last few centuries

February 6, 2025

Fresh audio product: Christian nationalism, Trump’s sovereigntists

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

February 6, 2025 Kristin Du Mez, author of Jesus and John Wayne, on Christian nationalism • Jennifer Middlestadt, author of this article, on “sovereigntism,” the foreign policy of Trump et al.

January 30, 2025

Fresh audio product: broligarchs and their scribes, the New York intellectuals

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

January 30, 2025 Eoin Higgins, author of Owned, on tech moguls and the journalists, like Glenn Greenwald and Matt Taibbi, who work for them • Ronnie Grinberg, author of Write Like a Man, on the mostly male, mostly Jewish New York intellectuals

January 29, 2025

More on union density: who and where

A follow-up to yesterday’s post about historical trends in union density. Today, a look at demographics and geography.

Once upon a time, the stereotypical union member was a factory worker. That hasn’t been the case for a long time. In 2024, manufacturing accounted for 10% employment and only 8% of union membership. In 1983, the numbers were very different: 22% of employment and 30% of union membership. Last year, not quite 8% of manufacturing workers were unionized—higher than private services, where it’s under 6%—but that’s down hard from 28% in 1983.

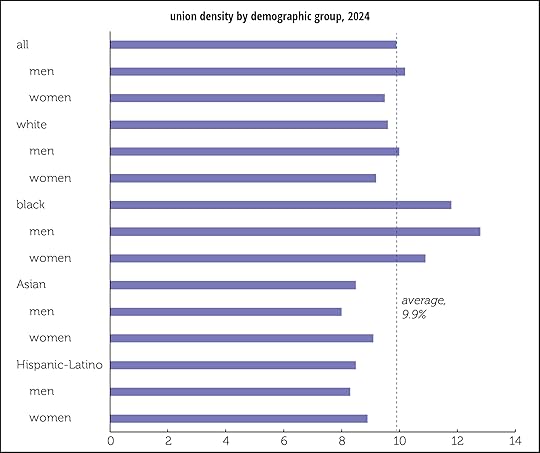

demographicsThat modal union member of the mind was also typically male. No longer. Last year, 10.2% of male workers were unionized, not much higher than the 9.5% among women. And notional modal member was often white too. As the graph below shows, union density is higher among black Americans than any other racial/ethnic group.

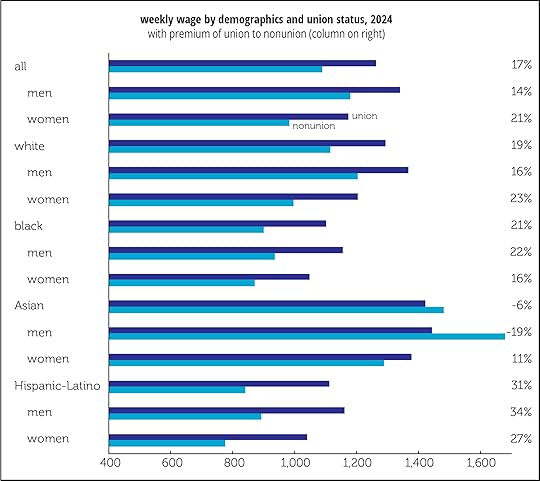

Unions also narrow pay gaps among disfavored groups (graph below). The union premium is higher for women than men, for Hispanics/Latinos and for black workers than for whites (see the column on the right for details). Unions narrow the black/white weekly wage gap by 4 percentage points and the Hispanic–Latino/white gap by 6 (not graphed, sorry). Sadly, that advantage has been narrowing over time as unions weaken, but it’s still significant.

Union density rates vary widely by state, from North Carolina’s 2.4% to Hawaii’s 26.5%. Details are mapped below.

High-density states are concentrated in the Northeast, the upper Midwest, the West, and offshore. The South is low-union land: of the ten states with a density under 5%, seven are in the South. As I noted yesterday, union density in the states of the former Confederacy averaged 4.3% last year. It averaged 10.9% outside the Confederacy—well over twice as much. W.E.B. Du Bois’s descriptions of the Southern labor market in Black Reconstruction sound quite familiar today.

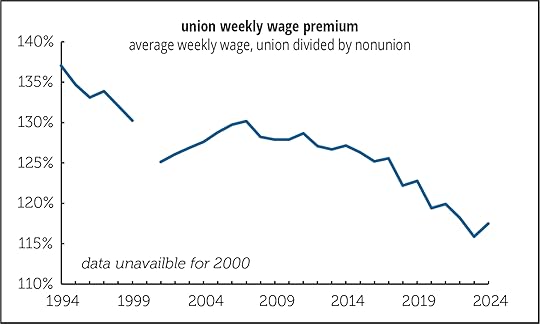

codaI usually end these density writeups with a homily. The union premium may be declining, but any premium >0% will inspire bosses to hate unions and want to destroy them—and not just for the higher pay. Unions are a constraint on bosses’ behavior; they can force them to be less racist, less abusive, and less able to fire. But clearly they’ve lost a lot of their bite over time.

And now my standard conclusion:

There are a lot of things wrong with American unions. Most organize poorly, if at all. Politically they function mainly as ATMs and free labor pools for the Democratic party without getting much in return. But there’s no way to end the 40-year war on the US working class without getting union membership up….

It’s still true, though I’ve got to up that count to 45 years or more.

January 28, 2025

Unions lose some more

Here are the headlines for my last five writeups of the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ annual accounting of union density:

Union density: yet another low (2020)

Pandemic boosts union density (2021)

Union membership resumes its fall (2022)

Union density keeps falling (2023)

Unions had a flat 2023 (2024).

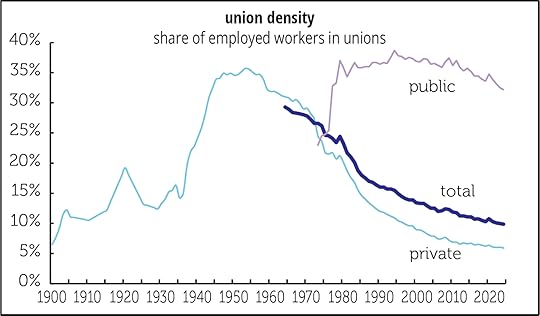

It’s not hard to detect a theme here: near-relentless decline. The only recent up year was 2021, which came about because more nonunion workers lost their jobs than union workers during the worst months of the pandemic, raising the density numbers. (Density is the share of the labor force that’s in a union.) Since 2019 (the subject of the 2020 report), it’s fallen from 10.4% to 9.9%. The long-term trajectory, graphed below, is almost unrelievedly downward. Private-sector density peaked in 1953, after rising sharply through the 1930s and 1940s, and has essentially collapsed. Public sector unions grew enormously from the early 1970s into the early 1990s, but after peaking in 1993, their density been heading down too, thanks to the state-level right-wing war on unions.

Since 1965, union density has risen only five times from one year to the next; it’s fallen in 49. Although one has to take stats from over a century ago skeptically, it looks like the private sector union share today is lower than it was in 1900. The public sector is back to 1977 levels.

A reminder why unions are important: the raise wages. The so-called union premium, the amount by which a union wage exceeds a nonunion wage, has been declining, but it was still 17% last year (graph below). Barry Hirsch and David Macpherson (see link below) adjust the premium for variation in industry, occupation, and demographics to isolate a pure union effect. Their data for 2024 isn’t out yet, but the adjustment does take a chunk out of the union premium, lowering it by about a third. But the premium is still a nontrivial 12% over the last five years.

More to come tomorrow on the union premium by demographic and union density by state.

A taste of the geographical story: union density in the states of the former Confederacy averaged 4.3% last year. It averaged 10.9% for the states that did not secede—well over twice as much. The planters came up with a durable labor market model.

Note on sources: The public sector data for 1973–1999 comes from Barry Hirsch and David Macpherson. Private sector data for 1900–1964 comes from Leo Troy and David Sheflin’s Union Sourcebook. Later data is from the BLS.

The Gaza ceasefire: an interview with Mouin Rabbani

This is a lightly edited transcript of an interview that I did with Mouin Rabbani on the January 23, 2025, edition of Behind the News. Rabbani is a journalist and analyst with a deep understanding of the Middle East. He has served as Principal Political Affairs Officer with the Office of the UN Special Envoy for Syria and Special Advisor on Israel-Palestine with the International Crisis Group. He is the co-editor of Jadaliyya, an ezine that covers the region, where he also hosts its Connections podcast.

I asked Rabbani to comment on Trump’s expressed desire to “clean out” Gaza—expel its inhabitants. I’ve appended those comments to the interview.

This ceasefire deal is nearly identical to the outlines of one proposed in May. What were the details of that proposal and then what happened? Why did it become OK eight months later when it wasn’t so good in May?

The deal consists of three stages. The first stage essentially consists of a temporary suspension of hostilities together with a limited Israeli–Palestinian exchange of captives and a surge in urgently needed humanitarian supplies into the Gaza Strip. The second stage, which is not yet finalized—the negotiations on which are supposed to begin on day 16 of the first stage, which is supposed to last for a total of 42 days—will see a larger Israeli withdrawal from within the Gaza Strip, a reopening of the border crossing between the Gaza Strip in Egypt, a much broader exchange of captives, and of course a continuation of the suspension of hostilities. And if the third stage is then concluded and finalized, then we’re really talking about an indefinite ceasefire and the completion of the exchange of captives. Or rather at that stage, any remaining bodies held by the Palestinians in the Gaza Strip will be handed over to the Israelis in exchange, I presume, for additional Palestinian prisoners and hostages and bodies held by Israel and the reconstruction plan that is supposed to be implemented under the supervision of Egypt and Qatar, the two main mediators of this agreement together with the United Nations.

As you mentioned, this multi-stage deal is essentially identical to the one presented by former President Biden in late May of last year, which Biden said at the time was not so much an American proposal, but rather a proposal that had been formulated by the Israelis and presented by the Americans in Washington. And now the Qatari Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Sheikh Mohammed bin Abdulrahman Al Thani (he holds both offices) have said that in fact, the deal is also very close to what had initially been proposed in December 2023, shortly after the temporary ceasefire and limited exchange of captives took place and then collapsed because Israel decided to resume the war.

As you mentioned, this multi-stage deal is essentially identical to the one presented by former President Biden in late May of last year, which Biden said at the time was not so much an American proposal, but rather a proposal that had been formulated by the Israelis and presented by the Americans in Washington. And now the Qatari Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Sheikh Mohammed bin Abdulrahman Al Thani (he holds both offices) have said that in fact, the deal is also very close to what had initially been proposed in December 2023, shortly after the temporary ceasefire and limited exchange of captives took place and then collapsed because Israel decided to resume the war.

What happened is that after Biden presented the Israeli agreement in late May, and then Hamas accepted it in early July of last year, something that Netanyahu did not expect, he began adding new conditions such as that Israel would maintain an indefinite presence in what is called the Netzarim Corridor, which essentially bisects the Gaza Strip into north and south, that Israel would maintain an indefinite—read permanent—presence in what Israel calls the Philadelphi Corridor, which is the border zone between Gaza and Egypt, that Israel would retain freedom of action within the Gaza Strip. Essentially the deal that Netanyahu is proposing is that Israel will retrieve all its captives and hostages and then resume its genocidal campaign in the Gaza Strip. And under Biden, the Americans went along with this. They basically claimed falsely, as we now know, that the only reason the deal was not being consummated was because Hamas was refusing to accept it.

Whereas we now know the real reason—and this has been made clear not only by everyone who has looked into this, but also by Netanyahu’s own negotiators—the real reason was that Israel kept proposing new conditions and changes designed to make it impossible for Hamas to accept an amended deal. And Hamas essentially said that they’re only going to accept the deal that had been proposed by Biden. They did show some flexibility in terms of the wording and the sequencing and so on, but there were no major changes.

So then as you rightly ask, well, what happened? Why is Israel suddenly accepting the agreement that it had rejected for the past half year? The key issue is that the American attitude changed. The incoming Trump administration made clear to the Israelis that the incoming president did not want a foreign policy crisis on his hands on the day he entered office, and he absolutely did not want a crisis on his hands.

That also included American hostages in the Middle East because several of the Israelis being held in the Gaza Strip are also dual nationals. In other words, they’re also US citizens. And it was as a result of basically Israel being given its marching orders that Netanyahu came to the conclusion it was not a very good idea to get on Trump’s bad side at the very outset of his tenure and went along with this agreement.

Trump had said on several occasions after the election that if there is no deal, there will be hell to pay. And everyone interpreted this as a threat to Hamas, which I’m sure it was, but it wasn’t a threat directed solely at Hamas. It was a threat directed at everyone involved: finish the deal and make sure there’s a ceasefire by January 20th.

Israeli analysts have also pointed out that there are other factors that have now made it easier for Netanyahu to accept the deal. One thing that we have now that we didn’t have last summer is that Israel has successfully eliminated two leaders of Hamas, has managed to decimate the leadership of Hezbollah, it has bombed Iran, and of course the Syrian regime of Bashar al-Assad has collapsed and is no more. That has led to improved poll numbers for Netanyahu and an expansion of his coalition, making it easier for him to accept the deal and lose a few of his coalition partners.

But then there is also the explanation that was put forward by the Biden administration, and particularly by former Secretary of State Antony Blinken. And can I just say what a relief it is to be able to say former Secretary of State Antony Blinken? He said that it was the pressure Hamas felt because of all these Israeli military achievements that I just mentioned, that finally compelled a weakened and isolated Hamas to accept what it had been rejecting throughout the second half of 2024. That’s a baldfaced lie, to put it politely, because first of all, Hamas had already accepted this agreement in early July 2024. And secondly, and more importantly, all these developments that were enumerated, the assassinations of the Hamas leaders, regime change in Syria, the decimation of the Hezbollah leadership and so on, took place after Hamas had already accepted the proposal. So, they were completely irrelevant to its calculations at the time that it made its decision to play ball.

You’d almost think that the Biden administration’s goal was to let Israel do all its destructive work, and it largely accomplished it. It decimated the resistance, it’s destroyed Gaza, and there’s not much left to bomb. It was just buying time to complete the work, and now the work is done.

That’s an entirely appropriate way to look at it. There’s virtually nothing left to bomb in the Gaza Strip now that there’s a suspension of hostilities.

We’d seen isolated pictures of that, but now that we can see this full landscape, it’s just appalling to look at. It’s like Hiroshima.

It’s probably a greater level of destruction than in Hiroshima—there’s literally nothing left standing.

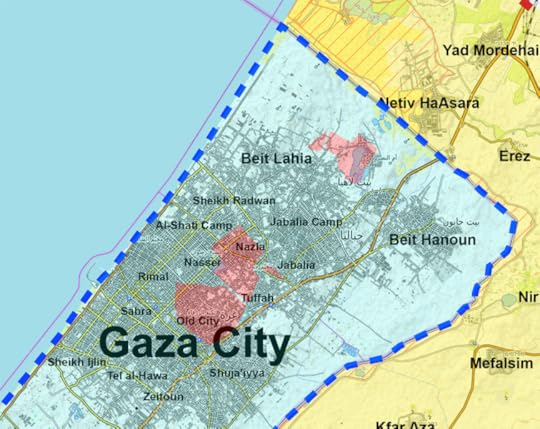

Having said that, just regarding your comment about Hamas, I can’t imagine that Hamas is not significantly weakened and depleted, but it was hardly a defeated organization. I mean, just in the last month in Beit Hanoun and Beit Lahia, the two  towns in the far north of the Gaza Strip immediately abutting the boundary with Israel, Israeli forces were incurring some of their heaviest losses during the past year. Because for all its losses and regardless of how much it had been weakened, it retains a capacity to fight and to fight coherently and to arm itself, and most importantly, to generate new recruits to replace those that it has lost.

towns in the far north of the Gaza Strip immediately abutting the boundary with Israel, Israeli forces were incurring some of their heaviest losses during the past year. Because for all its losses and regardless of how much it had been weakened, it retains a capacity to fight and to fight coherently and to arm itself, and most importantly, to generate new recruits to replace those that it has lost.

None of this agreement has anything to say about the future of the Occupied Territories, does it? I mean the long-term political solution to who will govern these places, who will own these places. That remains very much up in the air.

Yes, and those are in fact, two separate issues. There’s the issue of, let’s call it the day after scenario, which primarily concerns postwar governance, what type of government, what type of administration, and then there is a much broader and much more fundamental issue, which is the political future of the Gaza Strip in the context of the political future of the occupied Palestinian territory and the broader question of Israeli–Palestinian relations and all the rest of it.

On the first point, the reason there is no agreement on that is because Israel, since October 2023—and I should add to the frustration of its Western allies, and particularly in Washington—has refused to put forward any proposal of its own about post-war governance. The Americans have strongly promoted the idea of the Palestinian Authority, which is now ensconced in the West Bank, taking over the administration of the Gaza Strip, essentially entering the Gaza Strip on the back of Israeli tanks.

But this has been categorically rejected by Israel. Israel has certain point suggested that it can find client clan leaders to do its bidding, but that’s not working either. I think that reflects Israel’s vision that there should be no Palestinian future in the Gaza Strip. They’ve worked very hard to make this territory uninhabitable, unfit for organized human life. So why should there be any post-war governance there apart from the Israelis?

At the same time, I think Hamas also recognizes that it cannot simply reconstitute itself and maintain its hegemonic rule over the Gaza Strip the way that it has ruled the territory between its seizure of power in 2007 and October 2023. And in fact, a month or two ago, an agreement was reached in Cairo, under Egyptian auspices, between Hamas and the Fatah movement, which forms the backbone of the Palestinian Authority, according to which a government will be established in the Gaza Strip that is politically neutral, what’s called a technocratic government. That will not include personalities that are openly or clearly affiliated with either Hamas or with Fatah. These are supposed to be independent, but the body itself and its members will enjoy the consent of both parties.

Now, this becomes a little tricky because this is an agreement that was reached between Hamas and Fatah. It is being strongly promoted by the Egyptians, but the Jack-in-the-Box here is the Palestinian Authority leader, Mahmoud Abbas, who has yet to endorse the agreement reached by his own negotiators. I think what’s at play here is he doesn’t want to touch Hamas with a ten-foot pole because he’s concerned that even an agreement that doesn’t include any role for Hamas in Gaza governance, but includes governance with the consent of Hamas, will make it more difficult for him to engage with the Americans and potentially the Europeans as well. And the Israelis, of course, categorically reject any such agreement because from their perspective, one of their original war aims was not only to eradicate Hamas as a military force, but also as a governing authority.

Some people have expressed skepticism about the story that Trump’s envoy, Steve Witkoff, laid down the line with Netanyahu, and Netanyahu fell into line, saying this is just PR to buy some time to have a smooth inauguration. First of all, do you think this his story is believable? And longer term what next? Trump is talking about Gaza’s potential as a seaside resort. Jared Kushner said something similar last year. What do they have in mind? Do you have any sense of that?

I don’t know if they have anything in mind. Let me just answer the first part of your question first. We’ve had multiple reports from multiple sources providing details of the Trump transition team’s interactions with Israelis, and specifically about his Middle East envoy, Steve Witkoff’s meetings with Netanyahu. These seem entirely credible. The general tenor that the Trump administration read the riot act to Netanyahu and told him to get into line to me seems entirely believable. There isn’t a better explanation of why Netanyahu had been rejecting this agreement throughout the past six months, had never come under any pressure from the Biden administration to sign onto it, and all of a sudden, as soon as Trump’s people got involved.

The second, and I think more important part of your question, what do the Americans have in mind here? It’s much less clear because we do know that Trump’s people absolutely did not want a crisis on January 20th. Is that all they cared about? Are they now going to lose interest given that Gaza and the Middle East did not interfere with the inauguration? If they now lose interest, does this mean that Netanyahu can now derail the agreement after its first stage to ensure that the second and third stages of this agreement are not implemented, or will they remain on top of things and keep the pressure on to ensure that the rest of this agreement is implemented?

There are conflicting signs here. I mean, on the one hand, we have Witkoff not only saying that he intends to remain personally engaged, but there’s even suggestions that he will soon be visiting the Gaza Strip and in a quote attributed to him to ensure that there are no provocations to derail the agreement. And he then made a point of saying, and I’m not only talking about Hamas. Those are words would never have heard from any of Biden’s people.

And then there’s the larger context. Yes, they’ve talked about the Gaza beachfront as if this is essentially a real-estate deal and not a political crisis or a decades long issue of occupation and self-determination and so on. But I think the other issue here is that while we’re very much focused on US–Israeli relations, we would do well to pay equal attention to US–Saudi relations. And why am I saying this? You may recall that during his first term, Trump, through Prince Jared of Kushner, engineered a normalization agreement between Israel and the United Arab Emirates, then Bahrain, then Morocco, and the big prize was seen as Saudi–Israeli normalization. That didn’t occur. Biden made it the centerpiece of his Middle East policy, at least until October 2023, and even after that. He also didn’t achieve it. Will Trump now return to this item? Will he make this the centerpiece of his Middle East diplomacy? The reasons to believe that he will.

We then have to see how the Saudis respond. Will the Saudis simply go along with it without seeking to impose any conditions regarding the Palestinians simply to carry favor with the Americans the way that the Emiratis and the Bahrainis did? Will they assess that this is simply not going to happen because the Israelis are too extreme and won’t be willing and won’t be pressured by the Americans to make any significant political moves? And will the Saudis therefore focus much more on concluding a bilateral Saudi–American agreement? Or will the Saudis go to Trump and say, we want to do this. This is what needs to happen—an end to occupation, whatever other political arrangements that would fundamentally transform Israeli–Palestinian relations. You, Trump, get not only to sell many billions more of weapons, and we keep the Chinese role in Saudi Arabia limited, and we limit our relations with Russia, and as a bonus, you get a Nobel Peace Prize.

If the Saudis do that, Trump may very well go for it. That will of course, I think create very significant tensions in Washington between the various elements of his own constituency where you have kind of a collection of neocons, Israel-firsters, Christian evangelists, isolationists, people who feel that the US is being led by the nose by Israel, and so on. So, these are things I think that have yet to materialize and we’ll know much more in the next few months.

Does Trump have a clear agenda for the Middle East? If he does, who is going to be formulating that agenda? Or were they simply focused on the transition and don’t really care what happens next? And then of course, there’s also the broader question of Iran where conditions now are very different than they were during the first Trump administration.

Meanwhile, Israel is ramping up military activities in the West Bank. What’s going on there?

Just getting back to an earlier question of yours, another point that has been raised by a number of observers and analysts is that there was supposed to have been all kinds of negotiations and haggling and deal-making involved between Witkoff and Netanyahu, in other words, between the United States and Israel, and that Israel got a variety of US commitments in exchange for accepting the ceasefire deal.

I’m not persuaded when people talk about Trump agreeing to at least partial Israeli annexation of the West Bank. That may well happen, but that was already on the US agenda during the election campaign. My suspicion is that it was much more limited than that. Trump’s people basically told Netanyahu, these are your marching orders. This is what’s going to happen, and regarding any quid pro quo or what comes next, we’ll talk about that in January, February.

Now, as far as the West Bank is concerned, that was not an issue for the Americans because it didn’t have the same resonance. What that means is that Israel essentially has a free hand in the West Bank because it’s not really registering on Washington’s radar yet. Netanyahu is partially compensating for accepting this deal by very significantly ramping up Israel’s rampages by both the military and the settlers in the West Bank. This appears to have been part of a deal between Netanyahu and his finance minister, the far-right Religious Zionism movement led by Bezalel Smotrich, who unlike Ben-Gvir, did not leave the government but stayed within it. It seems that intensifying Israel’s rampages through the West Bank and land seizures and so on was part of that deal.

Finally, you alluded to this earlier, but let’s talk a bit more about it. Gaza is a wreck. It’s not possible to imagine any civilization being reestablished there. So, what’s ahead? What are we going to do? There are 2 million people who are essentially homeless?

Yes, 2 million people are essentially homeless. Israel’s initial intention, one, by the way, that was endorsed and embraced by the Biden administration and specifically by the former Secretary of State Blinken. The initial proposal was to transfer, in other words, to forcibly deport, the Palestinian population of the Gaza Strip to the Sinai Peninsula, open the border, pushed them all out, closed the gate. Problem solved. Blinken in fact, went to the region and met with officials in the Gulf States and in Egypt, and proposed this plan. And much to his surprise, Washington’s closest Arab allies categorically rejected it. It has been suggested that the Egyptian strongman, Abdel Fattah El-Sisi was in principle prepared to consider that but was met with very strong pushback from other power centers in the Egyptian security establishment. But my sense is that at least for the foreseeable future, that objective or that plan is no longer on the agenda. It’s no longer considered feasible.

I suspect what Israel wants to do now is to create conditions within the Gaza Strip where if you don’t have kind of an organized mass departure of Palestinians from the Gaza Strip, you’ll have a situation similar to what you’ve had, for example, in Syria or in North Africa, where people will get into boats or fishing trawlers or rubber dinghies, try to make it to the nearest island or land mass and either make it or drown in the Mediterranean like so many thousands before them.

Having said that, while I generally agree with your statement about the Gaza Strip, certainly in its current form, not being a viable place for human civilization, we do have somewhat of a historical analogy here, and that’s the late 1940s.

What I’m pointing to specifically is that the Gaza Strip did not exist before 1948. You had Gaza City, one of the oldest cities in the world, and during the British mandate of Palestine, you had the District of Gaza, which was very much larger than the current Gaza Strip. But the Gaza Strip itself is a product of the Palestine war of the late 1940s, and particularly of the Nakba, the mass dispossession and expulsion of Palestinians from territory that became the state of Israel, and overnight the population of what became the Gaza Strip, more than tripled from 80,000 to, I believe it was 240 or 250,000. These were all destitute, penniless, uprooted people who often entered the Gaza Strip on foot with only the clothes on their backs or on donkey carts. And they’re actually very detailed reports at the time from, for example, the Quakers, an organization that was quite active in the Gaza Strip during the late 1940s, and subsequently from UN agencies that were there.

Gaza’s infrastructure was certainly more prepared than it is today, but it was similarly in no way able to absorb three times the existing population. Yet, as I always say, one should never underestimate the resourcefulness and the persistence of the Palestinians of the Gaza Strip. We’re talking about people here who were under blockade and siege for 17 years, for a prolonged period were not even able to get fuel into the Gaza Strip to run their vehicles and found a way to use cooking oil to make their cars run and have taxi transportation and all the rest of it.

Yes, the challenges are going to be enormous. We don’t yet know to what extent they will be supported either by Arab states or the international community, or whether once the guns fall silent, if people will just move on to the next crisis. But this is an extraordinarily resourceful people that has managed to build a viable society out of nothing once before and may well succeed in doing so again, particularly if the underlying political crisis that is now in its eighth decade and that ultimately explains a crisis that erupted on October 7th, 2023, is also addressed.

That’s a big qualification.

Yes. I readily concede that point.

Mouin Rabbani’s comments on Trump’s proposal to “clean out” Gaza, written on January 28, 2025.

Trump’s proposal to relocate Palestinians from the Gaza Strip to Egypt and Jordan seeks to achieve under cover of humanitarian assistance what Israel failed to implement through genocidal warfare. Proposals for the ethnic cleansing of the Gaza Strip have a long history going back to the 1950s. In October 2023, Israeli leaders once again put forward a proposal to forcibly relocate the entire population of the Gaza Strip to Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula, which was adopted by the Biden administration, which sent its Secretary of State, Antony Blinken, to the region to market it to Washington’s closest Arab partners. He was categorically rebuffed, because the price of cooperating with such schemes would cost those participating very dearly. If Trump’s proposal is more than a trial balloon it will meet a similar fate. In the meantime, Palestinians are voting with their feet as hundreds of thousands of the displaced are moving to the rubble of northern Gaza rather than heading south to the Egyptian border.

January 23, 2025

Fresh audio product: Gaza ceasefire, sex work today

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

January 23, 2025 Mouin Rabbani on the Gaza ceasefire and Trump’s plans for the Middle East • Angela Jones and Bernadette Barton, co-editors of Sex Work Today, on that topic

January 20, 2025

Tariff follies

Our new emperor has a well-advertised love of tariffs. They appeal to his grandiosity, as dramatic imperial gestures that will bring the world to heel at no cost to Americans, given his stubborn delusion that foreigners, not consumers, pay the duties. Should he carry through with his threats to slap 10%, 20%, 30%, tariffs on imports—many of them on products that aren’t even made here, so there aren’t any domestic substitutes—prices will rise significantly, quite the turn for a guy who ran against Bidenflation.

I’ve written about Trump’s tariffs for Jacobin, notably their regressive effects, hitting the poor far harder than the rich, while doing nothing to stimulate domestic production, their intended purpose. (Between March 2018, when the tariffs were imposed, and January 2021, when Trump left office, steel production fell by 6%, almost twice as much as overall manufacturing.) All important, but now I’d like to take a quick look at tariffs in American economic history.

In his Truth Social post announcing the creation of an “External Revenue Service” (ERS), Trump made some outlandish claims. It will, as he put it, demonstrating his idiosyncratic understanding of trade (and strange capitalization practices), “collect our Tariffs, Duties, and all Revenue that come from Foreign sources. We will begin charging those that make money off of us with Trade….” Trade can be beneficial to both parties, though he makes it sound like a purely exploitative relation. And almost no one aside from him and his circle of advisers thinks that foreigners, rather than US consumers, pay tariffs,. But let’s set these issues aside for now.

Instead, let’s look at tariffs over the long sweep of history. According to a useful factsheet from the Congressional Research Service, tariffs were an easy way to collect revenues in the early history of the country, which didn’t have a developed administrative structure. There were only so many ships docking in so many harbors to unload goods. So, taxing that merchandise was not much of a technical challenge. The government was small and didn’t need that much revenue anyway.

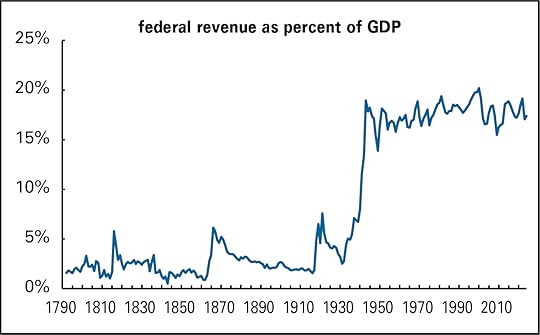

And government was small. From 1792 to 1930, federal revenue averaged less than 3% of GDP. (See graph above.) Obviously those old GDP figures are guesses, but let’s take them as a decent approximation of reality. From 1792 to the eve of the Civil War, 1860, tariffs provided an average of 86% of total federal revenue. There were some bumps before the Civil War, notably the War of 1812, which juiced expenditures and savaged imports. Besides borrowing heavily, the federal government increased excise taxes, reducing dependence on tariffs and leaving them accounting for just over half of federal revenues in the last third of the 19th century. With the introduction of the personal income tax (PIT) in 1913, tariffs receded in importance; since 1945, the PIT has accounted for 45% of federal revenues. (See graph below.)

(Speaking of federal revenues, the popular notion that taxation has been growing like topsy can’t survive fact-checking. As the graph shows, federal revenue as a share of GDP has been nearly flat for the last seven decades; in fact, the 2024 share, 17.1%, is below the 1951 share, 18.4%.)

With the growth of the PIT, and federal revenues generally, tariffs (or customs duties, to use the technical term) have largely disappeared as source of federal revenue. In the graph above you can see a spike around 1930, the time of the infamous Smoot-Hawley Tariff, which many, though not all, economists believe contributed to the Great Depression. Customs receipts barely cracked 1% of total revenue in the 1990s and 2000s. With the tariffs imposed during the first Trump administration, and preserved by Biden, that share doubled to an average of 2.0% from 2019 to 2022, but they eased back to 1.6% in 2024. The effective tax rate—customs receipts as a share of goods imports, graphed below—follows a similar trajectory: high in the 19th century, lower in the early 20th, and low and mostly declining since the end of World War II. That looks poised to change.

Since Trump has floated the idea of replacing the PIT with tariffs—switching from “taxing our Great People using the Internal Revenue Service,” as he said in the Truth Social announcement of the ERS—it’s interesting to experiment with how large those tariffs would have to be to plug the revenue gap. In the first three quarters of 2024, goods imports were $3.3 trillion at an annual rate, and the PIT brought in $2.5 trillion. Matching that would require a tariff rate of 70%. (Graph below.) The effective tariff rate last year—revenues divided by the value of goods imports—was under 3%.

Obviously a 70% tariff would decimate imports, but we’re not even considering that. And more than trivial increases would prompt retaliation from our trading partners, dinging US exports—and crafted to hit Trump-supporting regions especially.

It all seems like a stretch.

January 16, 2025

Fresh audio product: SF’s tech bro saviors, the Resnicks and California water

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

January 16, 2025 Laura Jedeed, author of this article, talks about San Francisco and tech moguls’ plans to “fix” it • Yasha Levine, co-director of Pistachio Wars, on the Resnicks and water in California

Doug Henwood's Blog

- Doug Henwood's profile

- 30 followers