Grace Tierney's Blog, page 24

June 21, 2021

Follow Roman Footprints to the History of Investigation

Hello,

Regular readers of the blog will know I love to read. I’m looking forward to #CosyReadingNight this Saturday (26th of June 2021) although I haven’t decided yet which book I’ll be reading – I’ve got five on the go at the moment, probably a tad over ambitous. One of the genres I enjoy is detective fiction – anything from Golden Age locked room murders to police procedurals and thrillers. When I stumbled upon the history of the word investigation I knew I had to share it here.

Detective Wordfoolery on the case!

Detective Wordfoolery on the case!Investigation entered the English language in the early 1400s, long before Sir Robert Peel’s “peelers”, the Bow Street Runners, or even little Miss Marple. It came from the Old French word investigacion and originally from Latin. Latin had the word investigationem (a searching for or into). This was compounded from in (same meaning in English) and vestigare (the verb to track).

Vestigare is where it gets interesting in my opinion. Vestigare comes from vestigium which means a track or a footprint. This means that the word investigation tracks back (pun intended) to following the footprints of the culprit.

The word vestige, which usually refers to the last trace of something which is disappearing (such as a species going extinct or a body part being out-evolved) also comes from the same roots. Although in that case those footprints of evolution are being traced by scientists rather than detectives.

Until next time happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

p.s. I’ll be taking part in CampNaNoWriMo next month, working on new episodes for my serialised novel “The Librarian’s Secret Diary”. Anybody else joining the challenge?

June 14, 2021

The Origin of Unscrupulous, thanks to a Stone in your Shoe

Hello,

This week’s word is unscrupulous, simply because I like and use this word and yet never really knew what a scruple was. A scruple sounds like a character in Dickens, doesn’t it?

The dictionary tells me somebody is unscrupulous if they show no moral principles and treat others in a dishonest or unfair manner. Although such people have existed since the beginning of human history the word itself is fairly recent. It was first recorded in the early 1800s as a compounding of un and scrupulous. Yes, scrupulous was a word first.

Naturally that put me on the hunt for scrupulous and I found extra meanings along the way. Scrupulous dates to the mid 1400s. It was in use for four centuries before we got its opposite word, unscrupulous. Scrupulous’ meaning isn’t the exact opposite, however. It has two meanings, the least used one is somebody who is concerned to avoided wrong-doing. The other you may be familiar with – a person or process which is careful, thorough, and attentive to details. There is no moral judgement needed for scrupulous with that meaning.

Scrupulous reached English from the Anglo-French word scrupulus, via French scrupuleux, and eventually from the Latin word scrupulus. You can also use the variants scrupulously and scrupulousness.

This led me to wonder – what is a scruple? Apparently it is (since the late 1300s) a pang of conscience or a moral qualm. It comes from the Latin scrupulus mentioned above. Scrupulus is the diminutive form of a scrupus which is a sharp stone or pebble. This was used by Cicero as an explanation for the pricking of your conscience being like having a small stone in your shoe, jabbing at you periodically as you progressed through your day. The same word, for some strange reason, was also used as a small unit of weight in English around the same date. Wouldn’t it be amazing if it was used to weigh your conscience?

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43BC), in case you’re curious, was a Roman statesman, scholar, lawyer, and philosopher. I particularly like his opinion that “if you have a garden and a library; you have everything you need.”

Until next time be sure to shake any scruples from your shoes before starting your day. Happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

June 7, 2021

Boxing Lingo – Phrases We Got From the Ring

Hello,

I was listening to a documentary today on the radio about Dublin’s National Stadium, the home of boxing in Ireland and the only purpose-built amateur boxing stadium in the world, and I couldn’t help noticing all the everyday phrases the English language has borrowed from the world of pugilism. I’m sure I haven’t compiled a comprehensive list so if you have more, feel free to drop them in the comments.

Pull your punches

If you don’t “pull your punches” when discussing a topic then you are brutally honest. This one is a direct borrowing from boxing where a pulled punch is one where the boxer holds back the full force of their blow.

Heavy hitter

An influential person or organisation is a heavy hitter in their area. This one dates to the mid 1900s and originated in boxing where a competitor who landed heavy punches was a heavy hitter.

Take it on the chin

To take it on the chin in life means that you have suffered defeat bravely. The idea stems from a fighter taking a a blow to the chin but managing to stay upright despite it all.

Below the belt

If an action is described as below the belt then it is perceived as unfair and deceitful. This is thanks to the rules of boxing which outlawed any punches below the belt of your opponent. The first rules were set out by Jack Broughton in 1743 and they were updated in 1867 by the Marquis of Queensbury (who is also remembered for his legal case against Oscar Wilde). Both sets of rules prohibited below the belt tactics.

Up to scratch

The scratch in this case referred to a rough line marked in the ground. Fighters put their foot to this line before the bout could begin. Now something is up to scratch if it is of sufficient quality. A related scratch phase is cooking from scratch or starting from scratch (beginning from the very basics) but in that case the scratch was the starting line of a footrace.

Boxing clever

If you’re boxing clever in life then you’re using your head to perform well. It started, as you might guess, in boxing rings. You’ll find a detailed explanation and early references from the early 1900s here.

Knockout

A knockout in boxing has been around since at least 1887 (and probably earlier) for the idea of stunning your opponent for a count of ten. By 1892 it was being used to describe an excellent thing or person and particularly for a good looking woman by the 1950s. You can also use it as “knock yourself out” meaning “to make a big effort”, since the 1930s.

Punchline

I wish I could claim this is a boxing one too and it’s tempting with punch in the word, but its etymology is unknown. A few possibilities exist though. The British “Punch” magazine was know for its jokes. Punch and Judy puppet shows in Britain certainly have Punch throwing blows as his long-suffering wife while making quips. However early use of the word appears to have been in American English and it may simply refer to a vaudeville comedian delivering a knock-out final line of a joke to their audience.

Can you think of any more boxing terms which have transferred into mainstream English? Please let me know in the comments.

Until next time happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

p.s. NF Reads were kind enough to interview me about creativity and my books this week. You can read the interview here.

May 31, 2021

Boondoggle – where Politics meets Boy Scouts

Hello,

Boondoggle is a fairly well known term in North America, but it was a new one to me when I met it this week.

A boondoggle is “an unnecessary, wasteful, or fraudulent project”. It can also be used as a verb if you are engaging in such a project. My first stop for further information, Etymology Online, told me the term entered American English in 1935 from an uncertain origin as a term for pointless “make work” projects for the unemployed during the New Deal era and also in 1932 as a Boy Scout woven braid.

Some colourful scout braids

Some colourful scout braidsThe connection to scouting reminded me of woggle (invented in the 1920s by an Australian scout) – the item which holds your neckerchief (scarf) together and which is often made of braided leather or cord. I always loved that word, it’s fun to say.

An article by Christopher Klein on History.com in 2015 provided a much more comprehensive history of boondoggle. Apologies to North American readers if it’s old news to them, but I’d never heard any of it before and found it fascinating.

It appears American Boy Scouts invented boondoggling during the late 1920s as a word to describe the knotting and braiding they did on camp to create colourful lanyards, woggles, and bracelets. It’s still popular today and is something I’ve done myself on similar camps. The word itself may have been coined by Eagle Scout Robert Link from New York, according to a scouting magazine in 1930.

The word wouldn’t have been used much outside of scout circles until the 4th of April 1935 when the New York Times reported on a federal programme which had spent $3 million on training hundreds of unemployed teachers in skills such as ballet, shadow puppets, and making boondoggles. The concept was to train those teachers to set up schemes in poor neighbourhoods to show children how to convert discarded items into useful gadgets. This early form of a recycling and disadvantaged youth out-reach scheme was painted as a waste of money by critics. Admittedly classes in ballet and how to run a circus might have been hard to justify at the end of the Great Depression.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt defended the idea in 1936 saying “If we can boondoggle our way out of the Depression, that word is going to be enshrined in the hearts of Americans for many years to come.”

The modern dictionary disagrees with his hope, recording a boondoggle only as a pointless waste of time and money. However if you need a woggle, a boondoggle is the best way to make one and scouts today, worldwide, are still committed to action on environmental issues and poverty.

FDR was a lifelong supporter of scouting in America, as outlined in this article. I can’t help wondering if he learned to boondoggle at any of the camps he attended.

Until next time happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@wordfoolery)

May 24, 2021

Mundungus – the Smelly History of a Potter Character

Hello,

I was gathering words starting with the letter M the other day, as you do, when I stumbled upon mundungus. As a fantasy fan the first thing I thought of was Mundungus Fletcher, a rather unsavoury criminal character in the Harry Potter series.

The author’s fondness for meaningful names is something I’ve explored in earlier posts. For example, Dolores Umbrage’s surname connects her to sadness and darkness while Albus Dumbledore’s first name links him to light and dawn. I’ve also been unearthing information about Professor Snape for my next book. I may need to go through the entire cast of characters, or perhaps I should leave that research rabbit hole to some future PhD student?

Mundungus, it transpires, is an old word for foul-smelling tobacco and was first found in English during the 1600s when tobacco smoking became a cultural norm thanks to the plantations in the New World.

Time for the old peg on the nose trick

Time for the old peg on the nose trickThe origins of the word add an extra level of unpleasant odour to the image. The word mundungus is a borrowing by English from the Spanish word mondongo. Mondongo describes a paunch, tripe, or intestines thanks to another word modejo (the belly of a pig). Tripe, in case you’re wondering, is another word for stomach. My own father ate it when he was a child, but I take a hard pass on that one personally.

All this means that if you call a person, or your novel character, Mundungus then you’re saying they smell like a cross between a pig’s stomach and noxious tobacco fumes. Delightful!

Until next time happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@wordfoolery)

May 17, 2021

A Tip from the Tea Shop – the History of Tipping

Hello,

This week’s word is tip, with thanks to an etymology tip I found in “Oranges and Lemons” by Christopher Fowler (wonderful detective series set in London, awash with historic tidbits). His character mentioned that if you visit Twinings Tea Shop on the Strand, the oldest in the world, you’ll find a wooden box with the gold printed initials TIP on it, standing for “To Improve Promptness”. If you wanted your tea a bit faster you’d drop a few pence in it from which we get the word tip. Naturally this piqued my interest.

It’s always good to leave a tip

It’s always good to leave a tipConsidering tip is a short word, it has a rather long and complex history. For a start it has two noun versions and four verbs. As a noun is can be the absolute point or top of something, that arrived around 1400, or shortly afterwards it gained a meaning as a light blow or tap.

The verb forms include;

(c. 1200, probably from German sources) to strike suddenly(c. 1300, probably from Norse sources) to knock something down or askew. This gives us tipping the scales, tipping point, and to tip one’s hand in card-playing(c. 1300, probably from Norse sources) to adorn with a tipThe final verb is the one we’re interested in today – to tip, as in to give an additional sum of money as a thank you for good service. Tip entered English in roughly this sense around 1600s as “to give a small present of money to”. It wasn’t associated with service at this point. It could be a parent giving a gift to a child, for example. The first record of giving a tip as a gratuity dates to 1706 – remember that date, I’ll be coming back to it.

However there is a large question mark over the whole “To Improve Promptness” idea. For a start there’s a fair bit of debate over what TIP stands for. In the 1909 book “Inns, Ales and Drinking Customs of Old England” by FW Hackwood, he reckons it stands for “To Insure Promptitude”. His book was reviewed in the same year by “The Athenaeum” and the reviewer poured scorn on Hackwood’s theory, implying it was a popular folk etymology without basis in truth. By 1946 TIP was being translated as “To Insure Promptness”. The variations don’t mean the acronym idea is false, but it definitely raises a warning flag.

Now let’s travel back to the Strand in London. This is where you will find the Twinings Museum, beside their tea shop. I have a huge fondness for small museums. They’re easier to visit than the vast labyrinths of the Louvre and other behemoths and are often run with a real passion. I think a wonderful way to spent my later years would be to travel to tiny museums around the world and this one has now gone on my “I want to visit” list.

Thomas Twining founded his tea shop here in 1706 (yes, there’s that year again) and has traded on the same spot ever since. Their website tells me that amongst their tea exhibits is “a non-descript wooden box labelled TIP, which is an acronym for ‘to insure promptness’; patrons of coffee/tea houses would drop a penny into the box to encourage quick service — the origin of tip“.

While I have my doubts about tip being an acronym, I suspect Thomas may have been the first well-known beverage seller to provide a tip box for his customers to add an extra gift for staff on top of their required payment. The word had been around with the meaning of small gift since the 1600s and as “an addition on top” since the 1300s. However I’m sure, regardless of the origin, anybody working in service industries will be very happy to receive a tip as shops and other establishments begin to re-open across Ireland today.

In case you’re curious, the idea of a tip-off being a bit of private information comes from the same roots and it dates to the 1800s. Perhaps such tidbits were first traded in Twinings tea-shop?

Until next time happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

Note: If you order through the affiliate links in this post, a tiny fee is paid towards supporting this blog. Alternatively you can drop me a tip in my digital tip jar at ko-fi.

May 10, 2021

A Man Called Freelove and the Fuel Bowser

Hello,

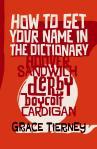

This week’s word is an eponym, bowser. Regular wordfools will know I wrote “How To Get Your Name In The Dictionary” to capture the stories of people whose names entered the English language as words – heroes and heroines (and a fair few villains) whose lives were extraordinary. Since publication I’ve stumbled across a few more. Perhaps there will be a second edition one day. Bowser is one of these and I must thank the QI Elves on the “No Such Thing as a Fish” podcast for putting me on the trail of this one.

First to meaning. What is a bowser? There are two definitions available. Bowser can be a noun for a dog. It was used in the early 1800s and probably comes from the old bow-wow idea for how a dog barks. I don’t think this is in common use anymore, but perhaps readers know otherwise?

The main meaning of a bowser now is that of a truck or pump for delivering liquids – most commonly water or aviation fuel. Water bowsers are deployed in England, for example, when there are water shortages. Fuel bowsers take on various jobs – refueling aircraft at the airport, bringing it to construction vehicles, and you can even have bowser boats to fuel larger ships.

Bowsers get their names from an American inventor called Sylvanus Freelove Bowser (1854-1938). Yes, that really was his name, isn’t it great? He is best know for the invention of the fuel pump for filling motor cars. With the arrival of motoring the world found a need to dispense set amounts of petrol or diesel into them but it wasn’t a liquid you could sell in a bottle or carton like milk or water as you needed large quantities. They needed a way to measure it as you drew it down, so you could be charged, but you couldn’t see it pouring, and because it’s a tad flammable you needed the system to be closed.

He began with a kerosene pump, patented in 1885, as kerosene was important for lighting and heating at the time. He dedicated twenty years of work to the finished concept and finished with the “self-measuring gasoline storage pump” in 1905. The pumps you use to fill your car in New Zealand and Australia are still called bowsers to this day. The same technology is still used, so you can think of him the next time you fill up your car (unless it’s an EV, of course).

Fuel up that car with a bowser

Fuel up that car with a bowserBowser’s pump invention also enabled the creation of the petrol station. For the first twenty years of motoring early drivers had to buy their fuel in two gallon cans from their nearest hardware shop, hotel, or garage.

The first petrol station in Britain opened in 1919 in Berkshire. Motorists were greeted by a uniformed staff member and a single hand-operated pump. The station was operated by the Automobile Association (AA) who, in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution (1917) were promoting UK produced benzole fuel (a by-product of burning coal) instead of Russian benzole. By 1923 there were 7,000 pumps across the UK and Ireland as a result of this initiative. With the addition of a canopy to keep you dry while you pump gas and a shop to sell sundries they became the type we use today, all thanks to Bowser’s fuel pump invention.

Irish readers should note that a bowser is unrelated to a bowsie which “The Dictionary of Hiberno-English” tells me is a disreputable drunkard or lout, unless they’re drinking from a fuel pump?

Until next time happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

Interested in eponyms like bowser? I’ve written a book about nearly 300 of them and the lives of the fascinating people who gave their name to English. “How To Get Your Name In The Dictionary” is out now in Amazon paperback (USA and UK), and ebook for Kindle,, and on .

Note: If you order through the affiliate links in this post, a tiny fee is paid towards supporting this blog.

May 3, 2021

Taking the Vagabond Path

Hello,

This week’s word is vagabond. Did you know that vagabond has two meanings? According to the Cambridge Dictionary it’s “a person who has no home and usually no job, and who travels from place to place” but Merriam Webster gives an additional definition “one leading an unsettled, irresponsible, or disreputable life”. I was thinking vagabonds were only disreputable in North America but my trusty Collins dictionary also gives them a negative description as a thief. Vagabond can also be used as an adjective, in case you need it.

Vagabond boots at Lugnaquilla, Wicklow

Regardless of whether a vagabond is an innocent wanderer of winding paths, or a criminal on the move, where does the word come from?

Vagabond was originally spelled as wagabund (it was in a criminal charge in 1311) and was used in Middle English as vagabounde. Early English spelling was erratic at best, but by the early 1400s English had vagabond. Despite that early legal charge, a vagabond was originally somebody without a home. The idea of them being in some way disreputable didn’t settle into the dictionary until the 1600s.

Vagabond is one the Romans gave us. It starts by compounding two Latin words – vagari (to wander or roam, related to the roots of the word vague) and bundus (to be) to give us vagabundus (wandering about). From there vagabundus wandered into Old French vacabond (wandering or unsteady) by the 1300s and hence, following the Normans, into Anglo-French as vacabunde, and finally into English as wagabund, vagabounde, and vagabond. The spelling of vagabond truly wanders all over the place, which seems immensely appropriate to me.

Until next time happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

April 26, 2021

The Obscure Word History of “In Camera” Court Proceedings

Hello,

This week’s word is the term in camera which is used to describe court proceedings held in private. I’ve always wondered what a camera has to do with this. Surely taking a photo, or video, of the court case would make it more public rather than less so?

Remember these? Cameras that used actual film

Remember these? Cameras that used actual filmAs with many legal terms this is one the Romans gave us. In camera simply means in private but how can camera mean private? The word camera entered English fairly late, during the 1700s, to describe a building with a vaulted or arched ceiling. It had, at this point, nothing to do with photography. They borrowed it from the Latin word camera which gives room words to Italian (camera), Spanish (camara), French (chambre). I was surprised to find it donated a similar word to Old Irish (camra) but when I thought about the modern Irish word for room (seomra) it does make sense.

The Latin word actually came from Greek roots (kamara), so we have to give the Greeks some credit too.

Shortly after it’s arrival, camera did get entangled with the early years of photography thanks to the camera obscura. This literally translates as a dark chamber. I’m not an expert on this technique but apparently is involves a black box with a lens which projects images inside the box of objects outside the box. I’ve a vague memory of entering one (perhaps at the London Science Museum?) and the image was inverted. There’s a very popular one in Edinburgh.

A camera obscura isn’t a camera in the modern sense as there’s no image retained afterwards. An advance on that was the camera lucide (light chamber) which used prisms to project an image onto paper beneath the contraption so it could be traced.

The camera obscura was often shortened to just camera and when modern photography hit its stride around 1840, the word camera was adopted for photographic equipment. Later it was also used for motion picture devices and of course now we all carry cameras in our pockets thanks to mobile phones, something they could only dream of back in the early 1700s.

While sometimes court proceedings, particularly these days, are filmed using cameras, when a case, or part of a case, is held in camera what it means is that the hearing will be held in a private room, often in the judge’s chamber for various legal reasons such as privacy for younger witnesses or to argue obscure legal arguments without unduly influencing the jurors.

Until next time happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

p.s. As regular readers know (by the way hello and welcome to our recent subscribers!) I sometimes write books about the history of words. You’ll find all the details here. The next one will be “Words The Vikings Gave Us” (out later this year). I’ve been plotting and scheming about which one to write next and as usual you’re the first to know. Next up is a mini word book about Christmas Words, after that it’s “Words The Weather Gave Us” and “Words the French Gave Us”. I’ll be busy for a while. If you suggest a word for any of the books I always make sure your name gets in the acknowledgements so feel free to tell me about your favourite Christmas, Weather, or French sourced words in the comments. Thanks!

April 19, 2021

Zephyr – How a Greek God Gives Us Gentle Breezes

Hello,

I’ve been thinking about weather words this week (I have plans afoot for a future book on the subject) so I chose one of my favourites to discuss today – zephyr. A zephyr is a gentle breeze (historically it was also a light cotton gingham, ideal for spring dresses). Not a word you use everyday but rather fun to use. Living by the coast I’m more likely to encounter gales than zephyrs but they are delightful when they arrive.

Where do we get such an unusual word from? Zephyr entered English in the mid 1300s from the Old English word Zefferus which came from Zephyrus in Latin and ultimately from Zephyros in Greek. Zephyros was the west wind and possibly related to zophos which described the west itself as a dark region filled with gloomy darkness. Not something you’d find in a tourist brochure.

However the Greek link yields far more information as those ancient Greeks loved to ascribe a god connection to nearly everything in their world so, of course, they had a god of the west wind.

One of my favourite sources for the more obscure tales of the Greek gods provided me with various tales of this one. You can read the full low-down there, but here are the highlights.

Zephyrus, the god of the west wind, was one of the four Anemoi – one for each major compass point. His brothers were Boreas (north wind and source of our aurora borealis of course), Notos (south), and Eurus (east, not the source of Europe, despite the similar spelling).

Zephyrus brought the milder west winds to Greece which heralded the growing season and hence he was venerated as the god of spring, a beneficial member of their pantheon. He was usually depicted as either a horse racing with the winds or as a handsome youth. In the later form he fell for a Spartan youth called Hyacinth but the young lad preferred Apollo and Zephyrus in a jealous rage caused a thrown discus to veer astray in the wind, hit Hyacinth, and kill him. The flowers of that name are said to have sprung from the blood of the slain lover.

Spring flowers

Spring flowersZephyrus did find love in the end though as he made a nymph called Cloris his wife. She became the Greek goddess of flowers and spring, the equivalent of Flora in the Roman pantheon.

If you get a chance to spend time outdoors this week and a gentle breeze passes by, remember Zephyrus and duck if any frisbees head your way.

Until next time happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)