Grace Tierney's Blog, page 21

December 30, 2021

Wordfoolery’s Favourite Books of 2021

Hello,

As you might guess, I love reading. I’ve taken a look back at my reading (59 books so far this year) during 2021 with help from my Goodreads account and here are 12 of my favourite books of the year. They’re not all recent releases, as books often wait in my Towering To Be Read Pile and because I’m still working my way through the 501 Books to Read Before You Die List. If you want to buy a book as a gift, or you want to treat yourself, I’d recommend any of these books. If you order through the links provided, a tiny fee is paid towards supporting this blog.

If you prefer posts about the history of unusual words, don’t worry normal service will resume next Monday. I only do this once per year.

They’re listed in random order. I can’t rank books, I love them too much.

London Bridge is Falling Down – Christopher Fowler

Another brilliant story about elderly detectives Bryant and May and their motley crew at the Peculiar Crimes Unit. If you love London, history, and witty detective fiction, this is for you.

Go Tell the Bees that I am Gone – Diana Gabaldon

Gabaldon writes the best historic fiction I know, effortlessly incorporating research on the role of Scottish emigrants in the American War of Independent while engaging you in the best depiction of a married couple in love I’ve ever read. Throw in some time travel, amazing supporting characters, and plenty of peril too.

Churchill – Andrew Roberts

Love biographies? Churchill lived a long life at the centre of things and Roberts covers it all – tough love from parents, mistakes in WWI, wilderness years, amazing leadership in WWII (when most would be retired), his worries about atomic bombs and the Cold War. Fascinating read.

Three Coins – Kimberly Sullivan

Escapist read – female friendship and romance in Italy as each of the trio finds their path to being happy. Read my interview with Rome-based indie author Kimberly here.

The Lost Man – Jane Harper

Harper regularly appears on my year end list. Thought-provoking Australian outback thriller. A brother dies of thirst. His siblings are the nearest suspects. What will this do to their family and remote community?

Project Hail Mary – Andy Weir

Wake up alone in deep space without memory of who you are and why you are there. Work it out. Get help from a very unexpected source. Save the universe. The best sci-fi writing of the moment I think.

A Good Girl’s Guide to Murder – Holly Jackson

Pip investigate a local murder as her school project, five years after the culprit committed suicide. She partners up with the alleged murderer’s brother and starts poking around but the real culprit isn’t happy as she uncovers a web of local secrets and several plausible murderers.

Traitor’s Blade – Sebastien de Castell

Three Musketeers meets Game of Thrones, our heroes spend the entire book on the run, and I lost count of the fight scenes (each different and believable), meeting corrupt nobles, a magic horse, and several intriguing women with stories of their own.

The Salt Path – Raynor Winn

How would you cope if you lost your home and your husband got a terminal diagnosis in the same week? This true story is an uplifting read that sings with hope. I highly recommend this to anybody who loves walking, the coast, nature, and honesty.

The Guest List – Lucy Foley

A page-turning read about a wedding on a remote Irish island for magazine running bridezilla and her Bear Grylls style groom. Limited guests, lights go out in the marquee during a storm, body found.

The Thursday Murder Club – Richard Osman

A murder solved by four retirees in their eighties who live in a posh retirement village. The friends – a nurse, a union boss, a probable spy, and a psychologist – meet to solve cold cases, for fun, so when a murder happens on their door step they get to work, outwitting the police along the way. Great twists and plenty of wine drinking.

Darkdawn – Jay Kristoff

The last in this great fantasy trilogy. We finally find out who is writing the snarky footnotes, meet a wonderful pirate, and Mia faces an even bigger and more dangerous challenge. Looking forward to re-reading this trio.

My three books inspired by this blog are out now in paperback and ebook (all the ways to get them are listed here along with reader reviews etc). “Words the Vikings Gave Us” explores the influence of Old Norse and modern Scandinavia on English. “Words The Sea Gave Us” covers nautical words and phrases from ahoy to skyscraper. “How To Get Your Name In The Dictionary” records the lives of the people whose names became part of the English language including Guillotine, Casanova, and Fedora.

Right, that’s enough book chat. Next week I’ll be back with strange and unusual words. Wishing you happy reading in 2022.

Until next time happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

p.s. this post contains affiliate links which make a small payment to the blog if you choose to purchase through them. #CommissionsEarned. Alternatively, you can use my digital tip jar to say thanks for this year’s words.

p.p.s. My fav books from 2020, 2019, and 2018 are also available.

December 27, 2021

Glimmer and the Glimmerman

Hello,

There’s something about dark December nights that lend themselves well to candles. The flickering glimmer of a flame brings something special to a room, doesn’t it?

Glimmer is one of those words whose meaning has changed completely over time. I always find them fascinating. A glimmer has been noun since the late 1500s and it means a faint, wavering light. However it is drawn from glimmer, the verb, which is older. In the early 1500s to glimmer was to shine dimly but in the late 1400s, when it first arrived in English, it meant to shine brightly. I’ve no idea how the meaning became so confused but at least it means you can definitely apply it to a candle’s flame as sometimes they are bright and sometimes they are not.

Glimmer arrived in English with thanks to either the Middle Dutch verb glimmen or the Middle Low German verb glimmern both of which have roots in the the Proto-Germanic term glim. Glim also gives us the roots of gleam and gleaming in English.

Glimmerman is not listed in either Merriam Webster or the Collins dictionary but I did find it in “The Dictionary of Hiberno-English” which I’m enjoying reading at the moment. Hiberno-English, in case you’re curious, is the particular variety of English spoken in Ireland. It has adopted many words and grammatical structures directly from Irish (Gaelic) and merged them with English over the centuries. It also retains a few Old English words which have fallen out of use in British English.

As it turned out I have a faint (glimmering?) personal link to the glimmerman “(colloquial) a Dublin Gas Company inspector during the war years who investigated contraventions of the rationing regulations (the “glimmer” was the minimal flame that could be obtained – illegally and dangerously – from the residual gas in the system when it was turned off)” (with thanks to the dictionary mentioned above). This is a reference to World War II, by the way, when the two or three glimmermen employed to cover Dublin city could enter a premises and disconnect them from the supply if they were cheating the gas supply rationing in this fashion. There’s additional information about them over on Wikipedia if you’re curious.

Several members of my father’s family across three generations worked in the Dublin Gas Company (1824-2006) during the 1900s, although none of them were glimmermen. I’m surprised not to find the word in British dictionaries, but perhaps gas wasn’t rationed in the same way there? If any British readers know more, please let me know in the comments.

Until next time happy reading, writing, wordfooling,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

December 20, 2021

Pass the Port – a Wordfoolery Christmas

Hello,

As this is my final blog post before Christmas 2021 I want to wish you all a very wordy Christmas and thank you for your support this year. I truly appreciate the comments, retweets, and shares. It’s wonderful to know other people love English words as much as I do. I’m also delighted to report that the Wordfoolery books have been doing very well too so the addiction to unusual words is spreading (insert evil cackle here). I can’t manage to post one of this year’s Wordfoolery Christmas cards to all of you, but I hope you like my water-colour and text art effort.

Happy Christmas from Wordfoolery

Happy Christmas from WordfooleryWith a draft book of Christmas words to choose from I’ve decided to delve into the Christmas Drinks chapter and share part of the story of port with you as a festive blog post. I was supposed to chat about it on the radio last week but we ran out of time. You can listen to the rest of the Wordfoolery Wednesday Christmas Edition on their podcast if you’d like to hear about how turkeys got their name, the very long, and secret, history of mince pies, and why we associate roasting chestnuts with this time of year. I will be drinking a glass of port on Christmas Day and I loved discovering the unusual drinking traditions associated with it. I hope you do too.

{extract from “Words Christmas Gave Us” by Grace Tierney, copyright 2021}

Port is a Portuguese fortified wine (typically 20% alcohol) often served with dessert or a cheese board, especially at Christmas.

Port entered English as a name for this type of wine in the 1690s as a shortening of Oporto, the city from which the wine was shipped to England. The city also gives its name to its country. Portugal, originally spelled Portyngale, came from the Medieval Latin name Portus Cale, the Roman name for the city of Oporto. Portus was the Latin for a harbour or port.

Port wine gained popularity in England in the 1700s when their war with France deprived drinkers of French wine and they turned to Portugal for an alternative.

Port drinking at the dinner table comes with a couple of fun traditions. The bottle, or decanter, should be placed to the right of the host/hostess. It is then passed between guests to the left, traveling around the table in a clockwise direction and ensuring everybody get a glass.

Of course if a guest fails to notice the decanter, or is trying to sneak a second glass, guests on their left may grow impatient. The polite custom is to then ask “Do you know the Bishop of Norwich?” to remind them and failing that “Is your passport in order?” (pass port, get it?).

The Bishop of Norwich story probably originated with Henry Bathurst who held that title from 1805 until 1837. He lived to the grand age of 93, with increasingly poor eyesight and a tendency to fall asleep towards the end of lengthy dinners. As a result, the port decanter often stalled at his place. Apparently Henry had a large capacity for wine and he was suspected at times of faking his slumber or inattention, to monopolise the port decanter.

{end of extract}

Until next time happy reading, writing, wordfooling, and don’t forget to pass the port.

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

December 13, 2021

Contumelious – a Useful Word for Difficult People

Hello,

If you’re the sort of person who loves unusual words then there’s nothing better than finishing a novel and scurrying off to discover a handful of new terms used by the author. Obviously you don’t want a writer who throws in words simply to display their vocabulary, but a handful of choice words, is like an extra gift to the reader.

One such writer in my experience is Diana Gabaldon and I’ve recently finished reading her latest novel in the Outlander Series (historic fiction/family saga with a twist of time travel), “Go Tell the Bees that I am Gone”, and gathered up a handful of new words, or at least new to me.

The lead character, Claire, is married to Jamie, a rather single-minded Scot. It’s a running joke how stubborn he is and at one point she is composing a list of terms for “bloody Scot” in her mind on this topic, one of which is contumelious (pronunciation here). I knew from context that is had to be about his sheer obstinacy, but anything ending in melious seems like it should be related to honey and sweetness (I was thinking of mellifluous) and with bees in the book title, and scattered throughout the story itself, I had to check it out.

British English dictionaries list it variously as American English or as archaic, so I’m using those as my excuse for not knowing it. It appears that while it was fairly regularly in use during the 1700s (the time period for that scene in the book), it has faded drastically since then.

It doesn’t appear to be a synonym for stubborn, however, as it is defined as rude, insulting, sneering, insolent, abusive, and humiliating – a pretty good term to use for somebody who has seriously annoyed you.

“Grumpy Tiki” – a wood carving by my DH whose Contumelious face adorns our garden

“Grumpy Tiki” – a wood carving by my DH whose Contumelious face adorns our gardenContumelious has been with us since the early 1400s. It arrived in English from Old French contumelieus, which was a direct borrowing from Latin contumeliosus (insolently abusive). The word was drawn from contumelia (insult).

There’s also a related word contumely which arrived a century earlier and describes abusive speech, from the same French and Latin sources. Contumelia is probably drawn from contumax (stubborn or insolent) so that must be where we get the link to Claire’s stubborn Scot. Contumax was used especially of people who refused to answer a summons to court. Con in this case is being used as an intensifying prefix but the tumax part of the word may be drawn from the Latin verb tumere (to swell up). There are several words in English which link anger or abusive people with the idea of them swelling up with their ire and I know I’ve mentioned them before on Wordfoolery, but the only one I can recall today is blowhard.

Until next time happy reading, writing, and wordfooling and good luck with avoiding contumelious people.

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

p.s. This post contains Amazon.com affiliate links which make a small payment to the blog if you choose to purchase through them.

December 10, 2021

Kimberly Sullivan & a Trip to Rome

Hello,

As a bonus post this week I’ve invited on a writing friend of mine, Kimberly Sullivan (a.k.a. KimberlyinRome), to talk about her debut novel “Three Coins”. I was lucky enough to see some early chapters from this feel-good tale set in Rome, and I really enjoyed reading the finished book (you can see my review on Goodreads). I also got her to share her favourite Italian phrase too, see below.

Congratulations on the new book, Kimberly. What got you started on the writing trail?

Oh, thank you, Grace! And thanks so much for inviting me to your blog. I’m so excited to have my first novel out. It’s been a dream of mine for quite a while, but until now I’ve only published short stories. I decided to indie publish my novel, Three Coins, and it felt like a big leap for me. I’ve been lucky enough to work with a great editor and graphic designers on this novel, and I already have the same team on board as I prepare my second novel for publication in April ’22 – this next one a time slip novel set in modern-day and nineteenth-century Bath, UK.

Can you tell us what “Three Coins” is about?

Three Coins is the story of three women thrown together by chance, who gradually become friends and learn to lean on one another to improve their lives. Emma, Tiffany and Annarita are three very different American expatriates living in Rome, Italy. As the novel opens, each is facing seemingly daunting challenges that find each woman at the breaking point.

Realizing the need to get away and regroup, each woman finds her way to a seaside resort close to Rome, thinking this will be an opportunity to reflect and return stronger. Of course, November is a dead period for these seaside resorts and these women are the only tourists in town. They meet at their hotel at a 1950s movie night, featuring the classic Hollywood film “Three Coins in The Fountain”. I thought it would be fun to revisit this 1954 tale in modern Italy, with three American women seeking happiness, love and fulfilling lives in the Eternal City.

“Three Coins” features three women, each in different stages in life, but able to sustain a strong friendship. Is that an important theme for you?

Absolutely. Friendship – especially of an unlikely nature – is often an important theme in my stories. In this novel, I wanted to find three women whose paths would not have crossed under normal circumstances, since they are all at different stages of life, work, financial stability, relationship status and family obligations. In literature, as in life, those random meetings can sometimes develop into the most enduring relationships. The burgeoning friendship and mutual support between these three women allows each character to rebound from her failures and to be braver working towards what she really wants.

Do you have an ideal reader in mind when you write? Who would love this story?

I am a big reader of women’s fiction, so I imagined the story would appeal to those who also like the genre, and following along on women’s journeys as they grow stronger and work towards their goals. I obviously hoped it would also appeal to those who, like me, enjoy a bit of armchair travel with their novels and (even better) with a touch of romance.

What has been the best experience so far in getting “Three Coins” out into the world?

Honestly, as a publishing newbie, I’m just so excited to finally have my first novel out there. But perhaps the best experience was working on my cover design. I love the graphic artists I worked with for my cover. We spoke about possibilities and how I also wanted to evoke the glamor of 1950s Rome in this contemporary story. The designers came up with a cover I absolutely love and consider so much fun, while still encapsulating the story. And as someone who adores graphic art, but has not one iota of artistic talent herself, I was thrilled to work with such talented artists to create this look. I can’t wait to collaborate again for my next book!

You blog too, about books and your beloved Rome, at https://kimberlysullivanauthor.com/blog/ – how on earth do you juggle it all? Any tips?

Yes, I’ve been blogging since 2012, posting twice a week: one post related to travel and one to either writing or reading. I wouldn’t be honest if I didn’t admit it is another time commitment, but my advice is to blog about topics you are passionate about… that way it still stays fun when deadlines loom large. And, alas, they always do.

Italian, and Latin, words crop up regularly on Wordfoolery and I enjoyed the way you scatter Italian throughout the book in a way that works even if you only know enough to order pizza and gelato (like me). What’s your favourite Italian phrase or word?

Ooh, this is a great question. Like you, I love words. And I also love studying foreign languages and grasping the differences of how one expresses oneself in different languages. My Italian husband and I raised our kids to be bilingual, but our dinner conversations can be quite funny to outsiders since certain expressions or feelings just “work better” in one or the other language, so our conversations often tend to be a bit of a mess switching back and forth. One of the expressions my children preferred in Italian is the term for best friend. In Italian, it is amico del cuore, which translates literally to ‘friend of the heart’. I loved that my kids felt the Italian term better expressed their sentiments.

As somebody who stops to look at every tiny historic detail in places I visit, I loved the little plaque at the Circus Maximus that the three women spot in the story. I have to ask, is that real or did it come from your imagination?

Yes! I am so glad you picked up on the plaque and asked about it, Grace, because the plaque is (or shall I say, was) very real and I knew I needed to work it into my story.

When I started writing this novel, my family and I were living close to the Circus Maximus, where this plaque was located, and I passed it each day. My children and I wondered at its cryptic message “I was lost” and a twenty-first century date in Roman numerals. Like my sons and me, Annarita, one of my characters, discovers this plaque and wonders what it is and why it was placed there. This plaque was too mysterious not to weave into my novel, where it serves as a reminder to all my characters as their lives are unfolding in ways they hadn’t envisioned.

Sadly, the plaque, which was obviously placed in that spot “unofficially”, has since been removed. I was so sad to pass by the first time I realized it was missing. Now, I only have a photo of it. But I’m pleased I was able to memorialize it as a part of my story. And I loved that it played a small role in encouraging my characters to pursue their dreams.

You’ve been living in bella Roma for a while now and it’s almost a character in the book. Reading it whisked me away from a rather damp, cold Irish November, to a warm pavement cafe in Italy, thank you! Will we be getting more Roman tales from you soon? What’s next on your writing To Do List?

I’m like you, I love to be whisked away to new destinations with novels. For me, these vicarious escapes through novels always feel like a mini holiday. Haha. Yes, I have been in Rome a good long while. That reminds me of when my older son was very young and he asked me, “Mommy, did you move to Rome before or after they built the Colosseum?” I have lived in Rome an awfully long time, but I do swear I was not around for the Flavian emperors’ impressive building project almost 2000 years ago.

And yes, Rome – and Italy in general – tend to work their way into many of my projects. My next release won’t be set in Italy (although it gets a tiny cameo!), but the projects I have scheduled after that are both contemporary/historical dual timelines: one set in the mountainous region of Abruzzo, with the historical segment during WWI, and the other set in Rome in the 1890s. I know short stories are a tougher sell in today’s market, but I also have a collection of contemporary short stories set all around the bel paese. I think Italy will continue to be an inspiration to me as I’m coming up with story ideas. Can you blame me? : )

Grace – thank you so much for having me on your blog! If readers are interested in my novel, it’s available on Amazon, Barnes & Noble and Kobo, with links to all sites at my author site. I’d love it if your readers would like to sign up for my newsletter or to connect with me on Instagram (@kimberlyinrome), Twitter or Goodreads. Thank you – Grazie!

Thanks, Kimberly. I should also mention that the e-book edition of “Three Coins” is currently reduced from $4.99 to $1.99 on all platforms (and similarly in other countries/currencies) until Sunday 12th of December 2021 so if you’d like a quick blast of Italian sunshine and happiness, you know what to do.

Until next time happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

December 6, 2021

Eponym Series: Jodhpurs

Hello,

Longtime Wordfoolery readers will remember that I sometimes blog on specific types of words – one being eponyms, and the other being nautical words (and I reserve the right to start another series someday). The eponym series inspired me to create the first Wordfoolery book in fact (available on Amazon US, Amazon DE, and all these other spots).

I have discovered it is impossible to be complete with any book about words. New words gain currency everyday plus it’s tremendously easy to miss a word which should be in the book despite spending at least a year (and in most cases several years) assembling my word list. This has proven to be particularly true with eponyms. I’m still gathering them and it’s not a short list. One day perhaps I’ll do a second volume on the subject, or launch a much expanded second edition, but in the meantime, here’s one of the ones I missed.

Jodhpurs entered the English language in 1899 as “jodhpur riding-breeches”, gradually changed spelling to be jodpores in 1912, and later settled as jodhpurs. They’re technically both a toponym (a word named for a place, such as paisley, turkey, or derby) and an eponym (a word named for a person, such as boycott, casanova, or montessori). They’re named after Jodhpur, a city in northwestern India. Nowadays Jodhpur is the second largest city in Rajasthan but it was historically the capital of the Kingdom of Marwar.

Jodhpur was founded in 1459 by Rao Jodha (1416-1489), a successful clan chief who also founded the kingdom of Marwar The city, and ultimately the riding trousers, are both named for him.

Jodhpurs are tight-fitting pants, with baggy fit over the thighs that horse riders wear. Jodhpurs originated in the city around the 1890s and were based on a traditional style of trousers called the churidar which are tight at the calf and baggy at the hips which are still worn to Jodhpuri weddings.

The arrival of jodhpurs to the English language was thanks to Sir Pratap Singh, the younger son of the Maharaja of Jodhpur. He had altered the traditional design somewhat around 1890 in India but when he visited Queen Victoria in 1897 for her Diamond Jubilee celebrations he brought along his polo team and their new riding trousers caused a sensation, probably helped by the large number of polo matches they won.

The British polo community were swift to merge Singh’s design with their own riding breeches and Savile Row tailors were soon creating these jodhpurs for their clients.

Until next time happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

p.s. This post contains Amazon.com affiliate links which make a small payment to the blog if you choose to purchase through them.

November 29, 2021

Investigating the Naughty and Nice Lists

Hello,

It’s the second last day of November and I’ve decided I’m on the Nice List. I’ve spent the last 29 days drafting most of a book about Christmas words and I’m sure Santa would approve. I passed the 50,000 words finish line in NaNoWriMo 2021 today (50,152 to be precise) and after a very busy writing, NaNoWriMo regional mentoring, and book promotion month (I had a ball at the #HistoryWritersDay online book fair on Twitter last weekend) I’ll be putting up my feet somewhat until the New Year. Never fear, I’ll still be posting here though, Wordfoolery is fun, not work.

My 15th win

My 15th winNaturally the new book has an entire chapter dedicated to Santa Claus and associated words like Rudolph, North Pole, Krampus, and more. While writing it, I investigated the naughty and nice lists and thought I’d share it today. Enjoy!

Extract from “Words Christmas Gave Us” by Grace Tierney, copyright 2021

Santa always has a strong interest in whether a child was naughty or nice and letters to Santa give children a chance to plead their case. Santa will always give them a second chance to avoid the dreaded Naughty List.

Naughtiness isn’t much more than mischief in most youthful offenders, but that hasn’t always been so, as demonstrated by the history of the word. When naughty joined English, spelled as nowghty or noughti (you just have to love early English spelling, don’t you?) in the late 1300s it had two meanings.

The first was to be needy, to have nothing. It was a way to describe somebody caught in poverty. The second was more judgemental, it described somebody as evil, immoral, unclean, and corrupt. That’s a pretty bad score sheet and it isn’t surprising that it would result in a zero presents result.

It acquired those meanings from the word nought or naught which was defined as nothingness, a trifle or insignificant person, the number zero but also as evil or an evil act. Somehow the number zero was equal to evil. This may explain some children’s aversion to studying the noble science of mathematics.

Over time the whole naughty is evil thing eased, thank goodness. By the 1600s somebody who was mischievous, disobedient, or improper would be called naughty, especially if that person was a child.

By the 1800s this also applied to an adult who might be promiscuous, but of course that’s not what Santa’s naughty list is about because he only brings gifts to the children of the world.

Like naughty, nice has changed meaning several times during its lifetime. It began in English in the late 1200s as an adjective for somebody who is foolish, ignorant, and frivolous. It had arrived directly from Old French from the Latin word nescius (ignorant or unaware) which translates directly from ne (not) and scire (to know). Scire is the same verb that gives us science.

By the early 1300s, nice meant timid or faint-hearted, by the late 1300s it was dainty or delicate, and by the 1500s it was precise or careful. That discovery made me laugh aloud as my English teacher in school insisted we never use nice in the modern meaning in our work, but only to indicate careful precision. She was only four centuries too late on that one. The precision meaning is retained in the phrase nice distinction.

By the 1700s, somebody nice was agreeable or delightful and in the 1800s we had added kind and thoughtful to that description. By the early 1900s it was declared to be a great favourite with the ladies “who have charmed out of it all its individuality and converted it into a mere diffuser of vague and mild agreeableness”. This was probably what my teacher detested. Certainly Jane Austen wasn’t a fan as she dedicates an entire scene in “Northanger Abbey” (1803) between Henry and Catherine to complaining about how the word nice had become a mild, and ultimately weak, adjective to describe anything from books to weather, walks, and people.

What about the infamous Naughty List and its more pleasant sibling, the Nice List? Neither appear in the stories about Santa until the song “Santa Claus is Coming to Town” was released in 1934 and became an immediate Christmas classic. In fact the song only mentions one list, although he does check it twice so it’s possible that Santa merely keeps a census of all the children in the world and marks either a tick or a cross to indicate whether their gifts should be loaded onto the sleigh on Christmas Eve. Either way, try to be good. We all want to be on the Nice List, right?

end of extract

Until next time happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

November 22, 2021

The Surprisingly Prayerful Origins of the word Gaudy

Hello,

It’s the last week of my NaNoWriMo challenge to write 50,000 words of “Words Christmas Gave Us” (I’m on 39,387 words). However this week brings the perfect writing storm as it’s a big week for book promotion, so I hope you’ll forgive me for taking one of the words from the draft Christmas book for this week’s blog. Also, I will be promoting my books this week on social media so if you’ve already bought them for yourself and your entire extended family then feel free to mute me until the 29th of November when normal Wordfoolery will resume. Now, let’s a take a look at the origin of the word gaudy.

While some like to deck their halls with subtle, elegant decorations at this time of year and others take a natural approach with evergreens, pine-cones, and various foraged items, there are those who believe Christmas is a time to Go Big or Go Home. You’ll know these homes by the clash of colours, strobe lights, and total decoration overload. Some of the latter group do it simply for fun while others go for it to such an extent that people from the area come to visit their homes and admire the display, leaving a donation for charity as they do so. It’s hard to be against such a thing, even if you think it’s a bit gaudy.

Gaudy arrived in English originally with the word gaud. A gaud in the mid 1300s was a large ornamental bead in a rosary. A rosary is a set of prayer beads used to help Roman Catholics keep count of prayers. The plural of a gaud was gaudeez.

At the same time period a gaud might also be a jest or trick, some form of deception. You could be gaudful and gaudless too, but those terms gradually fell into disuse.

By the end of the 1300s the idea of a gaud had broadened to include ornamentation (appropriately for its link to Christmas ornaments now), this was thanks to Old French gaudie (joy, playfulness, a flashy trinket) from Latin gaudium (joy) and gaudere (to rejoice).

Hopefully my decorations weren’t too gaudy

Hopefully my decorations weren’t too gaudy

By the early 1400s a gaud was being used as a term for a bauble or trinket which suggests that the beads in those rosaries were often very ornate rather than simple wooden beads for counting your prayers. In a deeply religious society, with regular church-going as a public event perhaps a decorative rosary was an important style accessory? A quick search online for historic rosary beads of that period seems to support this theory, at least for the wealthier members of the court.

Alongside this idea of showy ornamentation, the second meaning – full of trickery – persisted at least until the mid 1500s.

The showy idea may also have been influenced by a similarly spelled Middle English word gaudegrene from the same time which described a yellowish green dye extracted from the weld plant. This originally Germanic plant name became gaude in Old French, bringing with it the idea of colour to add to the idea of ornamentation – joining bright showiness to joy and rosary beads.

Around the 1550s you’d also have a gaudy day (day of rejoicing) and joyfully festive arose in the 1580s, all of which fits well with the idea of Christmas festivities although it wasn’t linked directly to Christmas. By the 1600s the meaning had shifted again, this time to the more modern idea of gaudy meaning showy or tastelessly ornate. Perhaps even then there were those who decried over the top ornamentation and joyful celebration. It might be no co-incidence the negative meaning was added in a century which saw the rise of puritanism and a crackdown on what was seen as overly pagan or “popish” celebration of the season.

If you like the idea of a gaudy day, do not fear, you can join in on the Wear Something Gaudy Day, celebrated on the 17th of October, inspired by a 1970s comedy show “Three’s Company”, mark it in your diary for 2022, if you wish. Gaudy days are also celebrated in several long-established universities and colleges in the UK, generally involving a feast and celebration thanks to the Latin meaning of rejoicing. I think we all need more rejoicing days, so this should be encouraged, even if the decorations are gaudy.

Until next time happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

p.s. Happy Thanksgiving this week to my American readers!

p.p.s. If you haven’t stumbled across my word history books here’s the lowdown.

“Words the Vikings Gave Us” Viking verbs & Norse nouns

“Words the Sea Gave Us” nautical words & sailor yarns

“How To Get Your Name In The Dictionary” heroes & villains who gave their names to English.

They’re available in paperback from Amazon, various online bookshops worldwide, some Irish independent bookshops, and signed copies directly from me (Christmas orders for signed copies close on the 10th of December – for Europe). The ebook editions are on Kindle and Kobo. All the info is at My Books and they make ideal gifts for the history buff or word nerd in your life. Anybody who buys any of the books (from any source) between now and December 31st, 2021 will be entered in a draw to win a viking bead necklace, nautical words bookmark, and a selection of Christmas chocolate – just message me an image of your receipt on Twitter @Wordfoolery or to grace at gracetierney dot com as proof of purchase. I’ll announce the winner here, and on Twitter & Facebook on the 1st of Jan 2022.

Don’t forget to check out the free download section where I have articles about boat names (from ark to schooner) and nine things you never knew about the Vikings. You might enjoy them.

If you’re on Twitter and love reading history (nonfiction or fiction) then be sure to check out #HistoryWritersDay on Sat 27 Nov and Sun 28 Nov 2021. It’s a a Virtual Christmas Market of Twitter accounts offering history books to buy. Loads of great authors, bookshops, and publishers are taking part, including me. I love browsing markets at any time of year but throw in history books and I couldn’t resist.

November 15, 2021

The Word History of Heroes

Hello,

Having explored the life stories of so many heroes, heroines, and villains for “How to Get Your Name in the Dictionary”, I realised this morning that I’ve never delved into the word hero itself. Mission accepted.

A hero is defined as “a person who is admired for their courage, outstanding achievements, or noble qualities”. After the last two years we’re all clear that heroes don’t always wear capes and often can be found in the most unlikely of places, showing up, getting the job done, caring for others.

Hero arrived in the English dictionary in the late 1300s to describe a “man of superhuman strength or physical courage”, although of course it can now refer to a female as well and sometimes the strength is spiritual or moral rather than physical.

Hero landed from Old French heroe which had come from Latin heros (whose plural is heroes) which described a hero, demi-god, or an illustrious man. We don’t talk about people being illustrious much anymore, that’s a shame. The Latin term was drawn from Greek hērōs (demi-god) but linguistic experts suspect the true origin was probably an older word.

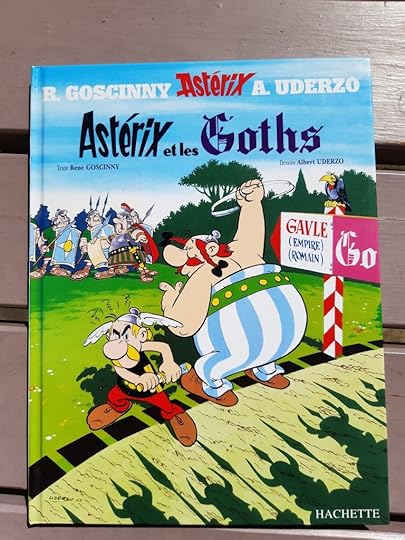

A hero of the Gauls

A hero of the GaulsThe Greeks were big on gods, to say the least, and demi-gods were legendary figures typically born of a union between a god or goddess and a human. Perhaps the best known of these would be Hercules and the tales of his twelve great labours. Considering one of his labours was to visit the underworld, capture its three-headed dog guardian Cerebus, and escape I think we can agree he fits the bill as being a good model for a hero, in the classical sense.

By the mid 1660s a hero in English was less of a demi-god and more of a brave man. By the end of the 1600s it was used in the sense of the lead male in a play or story, a use it has retained ever since.

Hero can be used to indicate either a male or female in modern English, although there’s also a female form, heroine. Much has been written about heroes and heroic actions, from being the hero of your own story to hero-worship and have-a-go-heroes, but knowing you walk in the footsteps of Hercules may inspire you to quiet heroics of your own.

Until next time happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

p.s. Today is the halfway point of NaNoWriMo 2021 and I’m up to 27,295 words on “Words Christmas Gave Us” – watch this space!

November 8, 2021

The Well-Traveled Word History of the word Tartan

Hello,

This week I’m resisting the urge to discuss Christmas words as I’m neck deep in festive research for “Words Christmas Gave Us” my book project for this year’s NaNoWriMo challenge. I’d been concerned that I wouldn’t have enough material for a full-length book with the topic but that has, thankfully, proven to be a misapprehension.

Instead I’ve turned my mind towards the upcoming release of Diana Gabaldon’s next book in the Outlander series later this month. The last volume was released seven years ago and I’ve already pre-ordered the new one from my local indie bookshop. The hero in the series wears his tartan kilt with pride so I’ve decided to delve into some fabric word history today.

Tartan from my youth

Tartan from my youthI should define tartan first, it’s a woven woolen fabric decorated with crossing stripes of contrasting colours. My first school featured a tartan kilt as part of our uniform, with matching bow-tie in the same pattern. That’s the design pictured above. I’ve no idea why a school in Ireland decided on a kilt and I know I was literally the only child in the school who wore the bow tie. My mother was big on the uniform code. I didn’t mind, I rather liked the bow tie. The kilt was scratchy though. Judging by more recent school photos I stumbled across lately, the tie is widely worn now.

Despite tartan being linked with Scotland now, its etymology dances across several countries.

Tartan became an English word in the mid 1400s for a woolen fabric. It probably came from the French word tiretaine (strong, coarse fabric) which in turn came from Old French tiret (kind of cloth) and ultimately from Medieval Latin tyrius (cloth from Tyre).

Tyre was an island city in the Levant (a region which includes modern day Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Palestine, and Jordan) and its name comes from Tyros in Greek, which comes from Hebrew/Phoenician tzor (rocky place). Tyre was particularly know for Tyrian purple, a dye made there in ancient times from a specific mollusc (murex brandaris). This so-called Imperial Purple was used for ceremonial robes in Roman life. There’s a very detailed Wikipedia page about its production and history if you’re curious.

The spelling of tartan was probably influenced in Middle English by tartaryn (rich silk cloth) a mid 1300s word which came from Old French tartarin (Tartar cloth). The Tartars were Central Asian people (more detail on them here).

It wasn’t until about 1500 that the specific meaning of tartan being the woven cloth with the crossing stripes pattern arose in English but the history of tartan cloth, as hinted at by its etymology is much older and more complex. Thankfully there’s a Scottish Tartan Museum who explain it much better than I can. The details below are drawn from their site, with thanks.

Firstly, plaid and tartan are not the same thing. Plaid comes from the Gaelic word for blanket and refers to a large piece of cloth, like the large piece used in a traditional belted kilt. These were usually made from tartan cloth, hence the confusion.

The earliest Scottish tartan dates back to the 300s but tartan patterned cloth has been found dating back to 3,000 B.C. in other parts of the world, so it wasn’t invented in Scotland. The weaving of tartan cloth was taken up locally by home weavers in Scotland and no specific clan tartans existed until around the mid 1700s. However the wearing of tartan became linked to Highland culture to such an extent that in the aftermath of the Battle of Culloden in 1746 the British government outlawed the wearing of the tartan as part of a brutal effort to suppress Scotland and any future rebellion against the crown. Thankfully the ban was lifted in 1782.

Commercial weavers, such as William Wilson & Sons produced more than 250 tartan designs by 1819 and named some of them for clans and towns. They designed their own and gathered patterns from around the country. Around this time those who had left Scotland and raised families overseas began to be interested in wearing tartan as a link to their homeland. The Highland Society of London wrote to clan chiefs to settle the matter but many of them weren’t aware of their clan’s traditional design. They consulted older clan members for memories, and firms like Wilson & Sons. Thanks to this and a royal visit in 1822 where attendees were expected to wear their clan tartan, most clans decided on a specific tartan for their use in future. There are now over 7,000 designs on record and many clans provide both a vibrant dress tartan design (often worn to weddings, for example) and a hunting tartan, generally in more muted tones which would blend well with the landscape while hunting.

I don’t think my old school tartan would hide me in the heather, so I guess it’s a dress tartan. Technically I’m allowed a few more designs if I ever fork out the money for a proper kilt as I’ve Clan Ferguson and Clan Johnston forbears from Scotland. Also as I’m Irish I’m entitled to the saffron kilt – a plain orange kilt (no tartan here!) which was imported to Ireland thanks to British army regiments. Decisions, decisions.

Until next time happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

p.s. It’s day eight of NaNoWriMo 2021 and I’m up to 14,044 words on “Words Christmas Gave Us” – watch this space!