Grace Tierney's Blog, page 20

February 24, 2022

Books to Make You Laugh

Hello,

Today, continuing my countdown to Ireland Reads Day tomorrow (25th Feb 2022), I’m exploring my long running love of funny books. Often underestimated and rarely featuring on book award shortlists, I think any book which gives you a laugh is one to be treasured.

I’ve just had a rummage on my shelves and found plenty of examples to share. I’ve reached that point in life which comes to all bookworms when you are forced to admit that unless you’re prepared to move house you may have to give away some of your books (gasp!). Yes, I know, it’s a wrench, but I console myself that they raise funds for charity and hopefully find a new reader if I let them go.

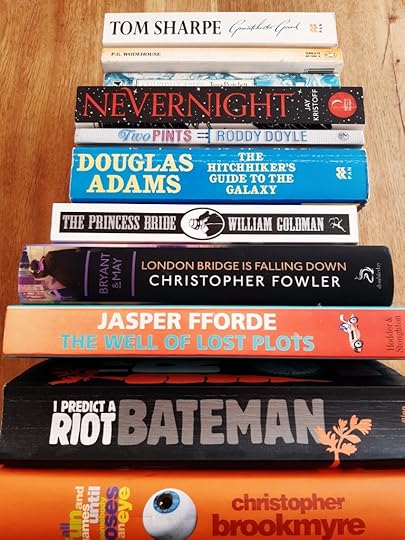

While I have made my peace with passing on thrillers, rom-coms, and general fiction the category I always keep is humour. The picture below, featuring many of my favourite funny writers, contains books I bought in my teens onwards, which is why some of the spines are faded.

Need a chuckle? Check these out.

Need a chuckle? Check these out.There are, of course, as many forms of humour as there are people in the world. We all have things which tickle our funny bone and it varies. I can enjoy a pun here and there, but others loathe them. The dark humour of Christopher Brookmyre’s thrillers has reduced me to tears on public transport (much to the bemusement of my fellow passengers), but it wouldn’t be for everybody.

I can’t help but notice the total absence of female writers in this pile. I know I read roughly 50:50 from male and female authors (I checked one year, out of sheer curiosity) but it appears I enjoy male humour, no idea why.

Some are old-school – if you haven’t tried PG Wodehouse’s delightful farces, you’re missing out and Tom Sharpe’s school stories are bitingly funny.

Some are old friends, often re-read – Terry Pratchett’s satirical fantasy world, I’m looking at you. I’ve reached the point where I can recite most of William Goldman’s wonderful romantic adventure “Princess Bride” but still love it.

Others are more recent discoveries. Christopher Fowler’s Bryant & May detective series is so clever and witty, while Jay Kristoff’s dark fantasy has the funniest footnotes ever (at least as good as Pratchett, and that’s saying something).

I’m pleased to include two Irish writers (drat, I forgot to include my beloved Oscar Wilde plays) – Roddy Doyle whose ear for Dublin dialogue is perfect and Colin Bateman who creates crazy plots set in Northern Ireland – he’s another who makes me laugh aloud.

That’s the key, I think. If a book can make me laugh, ideally in a quiet place, then it’s going on my shelves. Sometimes we need to read something funny. I know the Pratchett’s got me through exam stress more than once. Books are an escape to other worlds and smiling on the journey is a wonderful bonus.

I do my best to include humour in my word history books. Anybody who has ever looked at how words were spelled in Old English needs a sense of humour. If I’ve made anybody smile while reading, I’ll be very happy indeed.

Wishing you a very happy, and laughter-filled, Ireland Reads Day,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

February 22, 2022

Childhood Reading is a Joy

Hello,

Today, in honour of Ireland Reads Day this Friday (25th Feb, 2022), I’ll be chatting about childhood reads. As some of you already know I came to reading late. I struggled to learn the basics and reading a book with words instead of pictures seemed like an unpleasant chore to me until I was about 8. My teacher’s frustration didn’t help and going to the remedial reading lessons made me feel stupid, although I’m sure they were needed.

My avid-reader parents didn’t know what to do but my older sister passed me Enid Blyton adventure stories and that helped ignite a love of story and “what happened next” which I’ve never lost. I slogged my way through the Famous Five, Secret Seven, St. Clare’s, and Mallory Towers. Then, when I was 9, my new teacher read us “The Hobbit” by J.R.R. Tolkien each week during the school year.

I was hooked and waited eagerly for the next installment but we reached June and the school holidays and Bilbo Baggins hadn’t met Smaug yet. I explained my predicament to my father who took me into Dublin on the bus to Easons on O’Connell Street where he bought me a brand new copy of book, complete with evil dragon and golden hoard on the front and a cool fantasy map inside. I signed it and added my age, 10, to the inside leaf.

I became the child who reads well into the early hours to finish a story, the one who is accused of “eating the dictionary” because her vocabulary is wide, the one who mispronounces words because she found a word in a book rather than in speech, and the one who loved Easter holidays because she could curl up in her bedroom with books and chocolate eggs for a glorious two weeks.

I also re-read “The Hobbit” every year.

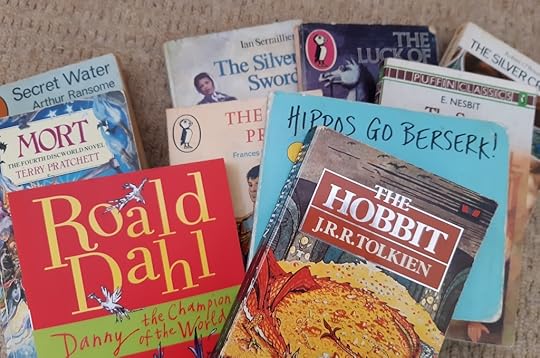

A selection of my childhood books

A selection of my childhood booksI grew up at a time when YA didn’t exist, this totally confuses my teens. I moved directly from Enid Blyton to Charles Dickens and happily alternated between Snoopy cartoon books and Agatha Christie or Alistair Maclean. My parents didn’t care what I read, as long as I was reading.

As somebody who now writes her own books, what books can I suggest for modern readers of a youthful disposition? Some classics still hit the spot. Roald Dahl, Dr Seuss, and Tolkien still shine but some of the Victorian and Edwardian books I loved are a struggle for younger readers now. If you love Hogwarts you might try Enid Blyton and Angela Brazil boarding school books, but they don’t have magic. “Alice in Wonderland” still works too with its imaginative freedom.

Don’t forget nonfiction, I got hooked on history through books about myths by Roger Lancelyn Green (plus my father’s massive tomes on the American Civil War).

Amongst the books I saved and passed on to my own children – Frances Hodgson Burnett and E. Nesbit’s books are wonderful escapism and modern readers have the extra joy of movies about the Secret Garden and the Five Children and It. Arthur Ransome books are perfect for a child who loves the sea and sailing and are probably why I wrote “Words the Sea Gave Us”.

I didn’t own many picture books myself, but they were much loved when my children were younger. Sandra Boynton’s hilarious “Hippos Go Beserk” is the only book I can recite because I read it so often. We also loved “The Gruffalo”, “Mr Wolf’s Pancakes”, “Where’s my Cow?”, “The Happy Hedgehog Band”, the Winnie the Witch series, Harry and his bucketful of dinosaurs and whatever you do, “Don’t Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus”.

Nowadays I’m drawn into books by my teens. They like to discuss them so I’ve read and loved “Hunger Games”, “Divergent”, “Six of Crows”, the Skullduggery Pleasant series (set in Ireland!), and many more. I’ve been told to mention book tok on TikTok as a good source of recommendations for YA readers. “Paper Girls” and Manga books are worth checking out too (JoJo, Clash of Titan are popular around here).

One final mention must go to Terry Pratchett and his Discworld Series (I suggest starting with “Mort” and going from there) which got me through my Leaving Cert and university exams with their wit, intelligence, and sheer page-turny-ness and are much loved by my youngsters too. This blog is called Wordfoolery thanks to one of his characters.

What advice can I give to a young reader?

Read what you like. Your local library has everything so gather a selection and try them. If you don’t like it, stop reading and pick up another. Books don’t mind if you’re a boy or a girl. Words don’t mind if you can’t understand every single one – skim past the hard ones, understanding will come if you keep reading (and a dictionary, or helpful adult might help if you really need to know). It’s OK to read books with lots of pictures until the words get easier. I still read books with pictures (check out Chris Riddell’s Goth Girl books, they’re So Beautiful). If you don’t like made up stories, try nonfiction (and vice versa).

If you find a book you love, go to your teacher/librarian/parent/bookseller – tell them and ask for more. They can help.

And parents? If you’ve babies/toddlers try putting their books on the lowest shelf in the house – they will pull them out and play – that’s a good thing. Read to them – this really works. Read yourself where they will see you. Our children copy us, set a good example. When mine were 9-12 we logged all their reads and when a sheet was full (about 20 reads) we went to the bookshop and paid for a book of their choice with zero parental input. They chose well every time and adored the trip (this could be done via the library or second hand bookshop too).

Older children? Ask them to recommend a book for you, read it, talk about it. If there’s a movie of it too, watch it and enjoy the eternal book vs. film debate.

I read every day and I’ll never stop. Thank you, Mr. Baggins.

Wishing you all a very happy Ireland Reads Day,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

February 21, 2022

Ireland Reads 2022

Hello,

I’m guessing that if you enjoy the Wordfoolery blog (fooling with unusual English words since 2009) you’re probably already reader, but do you know that Ireland has an entire day dedicated to celebrating reading in all its forms? It’s called Ireland Reads, it’s on the 25th of February annually, and I’m a Reading Ambassador for the initiative on behalf of the Louth Library Service.

The idea is that you sign up at the Ireland Reads website, pledging to read for a certain amount of minutes, or hours, on Friday the 25th. They’ve a brilliant book suggestion tool there too with thousands of ideas provided by librarians around the country. I’ve pledged two hours as I think the day is a wonderful excuse to read, but even fifteen minutes counts as they dare you to #SqueezeInARead (hence the lovely graphics of readers in tiny spaces). Technically it’s for people reading in Ireland but I’m sure if you were signing up from elsewhere they wouldn’t mind. You could always try a book by an Irish author.

I’ll be blogging about Ireland Reads this week (don’t worry, the unusual words will resume next Monday). As Louth Libraries is particularly aiming to get children reading on the day this year I’ll be chatting about the books I loved as a child and because I love fiction with a touch of humour I’ll be posting about funny books too. On Wednesday 23rd Sinéad Brassil and I have turned over part of Wordfoolery Wednesday on LMFM radio to book chat so if you’re local please tune in (or you can catch the podcast later).

They also asked me to create a video about Ireland Reads, including a reading from my most recent book, “Words the Vikings Gave Us”. If you’d like to admire my unusually tidy and dust-free bookshelves you can check that out here. It’s my first ever video book reading so please excuse any hesitations.

Some other bookish Wordfoolery posts you might enjoy –

Seven Fun Ways Back into Reading

Eleven Ways to Squeeze in a Read

Wordfoolery’s Favourite Books of 2021 and 2020, 2019, 2018. I’m not a book blogger but I read about 60 books each year and I pick out my favourites each year to review at year end so other readers can find and enjoy them as much as I have. I’m also very active on Goodreads, so feel free to friend me there to read my reviews.

Hopefully you will join me on the Friday the 25th in picking up a book and squeezing in a read. Any type will do and of course audio books, graphic novels, nonfiction, genre fiction, poetry, and screenplays all count too.

Until next time happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

February 14, 2022

The Two Meanings and Histories of Cleave

Hello,

This week’s word is cleave – with thanks to friend of the blog, Rick Ellrod who asked me to check out why we can say “cleave unto” somebody in a unifying or romantic sense but also use a cleaver to cut something apart. Yes, it may be Saint Valetine’s Day, but I’m thinking about meat cleavers as well as romance.

A romantic cleaver?

A romantic cleaver?Regular readers will know that words sometimes change meaning during their lifetimes. The older the word, the more likely that is to happen. You can even end up with the final meaning being the exact opposite of the original and that’s what I expected to find in this case.

I was wrong.

To cleave, meaning to split or divide, entered Old English originally spelled as cleofan, cleven, or cliven from a Proto-Germanic root word kleuban which gave similar terms to Old Saxon, Old Norse, Danish, and German. Its past tense is recorded from the 1300s, so it’s a fairly old word in the English dictionary. You might know some of its verb variations – cleft and cloven (think of a cloven-hoof, for an example) – which all relate to splits and divisions.

None of this appears to have anything to do with romantically joining with your beloved soulmate by cleaving to them. The answer is surprisingly straightforward and simple for English etymology – the other cleave, despite identical spelling, is a totally different verb in English, and in other languages.

Cleave, meaning to adhere or cling, entered Middle English as celvien or cliven, from Old English clifian or cleofian. The word came to Old English from West Germanic klibajan (to stick or cling) and a PIE root word gloi (to stick) and it generates similar terms in Old Saxon, Old High German, and Dutch.

Despite having the same spelling in modern English the two cleaves were different in Old English and come from different roots – one Germanic and the other Indo-European. The spellings may have converged in English naturally as both words were used and spoken. Cleave to may be rarely used now, but it was an equally popular verb originally.

Nowadays, perhaps to avoid confusion, you’re more like to hear about stick and split for these meanings, but feel free to continue cleaving, in whichever form makes you happy.

Until next time, happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

February 7, 2022

The Playful Roots of Ludo and Ludicrous

Hello,

These week I’ve investigated the etymology of ludicrous. Along the way, as often happens, I veered off course to check out ludo as well. That’s the problem with the history of words, you can easily be distracted into side alleys.

Ludicrous is one the Romans gave us but it didn’t land in English until the early 1600s when it had a different, and now dead, meaning – relating to play or sport. It arrived via Old French ludicre (sportive), Latin ludicrus (same meaning) and ludicrum (a game, toy, or joke), all of which are rooted in the Latin verb ludere (to play).

The Wordfoolery jester wears a ludicrous hat

The Wordfoolery jester wears a ludicrous hatBoth ludere and ludus (a game) come back to the root word loid (to play) which provides similar words in Middle Irish, Greek, Albanian, Lithuanian and Latvian (although a couple of those are linked more to giving birth than to playing and I really cannot fathom that link!).

Clearly ludicrous’ meaning changed over time. Its modern meaning of something being ridiculous or open to provoking ridicule dates to the late 1700s. The Latin verb ludere (to play) also gave rise to other English words, allude and allusion, via French again (alluder) which in the early 1500s had an original meaning in English of mocking or making a joke. The modern meaning of making a passing reference wasn’t too long in arriving though and is the one which lasted.

It was at this point that I had a light-bulb moment and wondered if the popular board-game ludo might be related to all these playful Latin verbs too.

Ludo is a board game for 2-4 players where players race to get their four tokens from start to finish according to dice rolls. Its simple rules made it very popular in my house when my children were younger and the random chance from the dice meant adults, older siblings and younger children all have a fair chance to win. Nowadays you’re more likely to find us playing Monopoly, Cluedo, or card games.

Ludo has been the game’s name in England since the late 1800s but you may know it under a different name such as uckers or parchisi. Parchisi originated in India in the 6th century, there are even cave paintings of people playing it. This is another word derived from the Latin verb ludere (to play) as it literally means “I play”. However I didn’t find any evidence of the Romans playing ludo. They did, however, enjoy board games and strategic games, as explored here.

Until next time happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

January 31, 2022

Pulling a Lugubrious Face

Hello,

I overheard somebody saying lugubrious the other day and I can’t recall the last time I heard it or used it myself. I hope this word isn’t slipping from use as it’s a delight to say and perfectly fits certain situations. If you’re not sure on the pronunciation you can find it here along with its definition as mournful or dismal, particularly in an exaggerated fashion. You might say, for example, “the teenager’s mood was matched only by his dismal and lugubrious brooding”.

This word is one the Romans gave us. It arose in English around 1600 and was originally spelled as lugubrous. It was compounded from the suffix -ous which we use widely in English (splendiferous, for example) and lugubris, a Latin word meaning mournful or relating to mourning. Lugubris comes from the verb lugere (to mourn) and ultimately from the root word leug (to break or to cause pain). That root also gives rise to lygros in Greek (mournful or sad) and rujati in Sanskrit (breaks or torments).

In modern English being lugubrious isn’t always directly linked to mourning and grief, but can be for any form of downheartedness. Although they are rarely used you can also deploy the related words lugubriously, lugubriousness, and lugubriosity (sadness, since 1839).

In the past there was another English word from the same leug root word, luctual. It’s an adjective meaning sorrowful, so pretty similar to lugubrious in meaning as well as etymology but it faded over time, leaving lugubrious all alone and perhaps even more mournful.

On that cheerful note, until next time happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

January 24, 2022

The Word History of Colours – Turquoise

Hello,

I’ve always been fascinated by how we name colours. I’ve already covered mummy brown (yes, real mummies in that paint), the gory history of magenta, rhymes about colours, cerulean, vermillion, and the medicinal use of lapis lazuli. This week I’m taking a look at turquoise, that striking blue-green shade, and one I’m fond of myself.

My turquoise top (yes, it has more green tone in real life)

My turquoise top (yes, it has more green tone in real life)Turquoise is an opaque blue-green mineral which is a hydrated phosphate of copper and aluminium (yes, I had to look that one up). If you believe in such things it is associated with the Saggittarius star sign.

Turquoise was used in the decorative arts of many ancient civilisations including Egypt, the Aztecs, Persia, Mesopotamia, India, and China. Possibly the best known use is in Tutankhamun’s iconic gold and turquoise striped burial mask.

Turquoise is this stone’s most recent name. Pliny the Elder called it callais (from an earlier Ancient Greek word) and the Aztecs called it chalchihuitl (don’t ask me to pronounce that one).

The Middle English term for turquoise was turkeis (or turtogis) in the late 1300s but in the 1500s this was replaced by turquoise from the Old French word turqueise (Turkish) in the phrase pierre turqueise (Turkish stone). This colourful stone gained the name because it was imported to Europe from lands ruled by the Ottoman Empire. The stone has similar names in other languages for the same reason. You will find turquesa (Spanish), lapis turchesius (Medieval Latin), turcoys (Middle Dutch), türkis (German), and turkos (Swedish). The habit of naming things turkey or turkish thanks to their Turkish exporters of course is also where we get our Christmas turkeys.

By the late 1500s people were using turquoise as an adjective to describe other things which were turquoise coloured such as fabrics and by the 1850s it was simply a name of a colour.

Until next time happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

January 17, 2022

Are you Nonplussed? Blame the Romans

Hello,

I’m currently reading a dictionary of Hiberno-English (the specific variety of English spoken in Ireland) because sooner or later if you write about the history of words you find yourself acquiring and reading dictionaries, for fun. Yes, well, I’ve always been a bit strange.

I came across a word in it which I’ve never heard or read in Ireland – namplush – which is defined as the state of being unready or at a disadvantage and is an English dialect word derived from nonplussed, which has Latin roots. Always ready for a quick trip into the Roman past, I headed for my other dictionaries for more information on nonplussed.

Some Roman ruins to get you in the Latin mindset

Some Roman ruins to get you in the Latin mindsetNonplussed is the state of being perplexed or confounded and it landed in English around 1600. To nonplus somebody is to put them in that state of confusion where they are unable to decide or proceed (1580s). The idea is that when you are nonplussed nothing more can be said or done and it’s a borrowing from Latin non plus (literally this means no more).

This set me on the trail of the word plus and the plus sign (+). Plus in Latin means more, in greater number, or more often and it arrived in English around 1570 so it didn’t take long to find itself in nonplus thereafter. Plus arose from an Indo-European root word, pele (to fill). Clearly people have been adding numbers for many centuries before the 1500s, both in Rome and Britain.

The plus sign was well-known by the late 1400s and is possibly an abbreviation or shorthand for the Latin word et (think about how similar the letter t is to a + sign). Et means and in Latin and in French, it’s best known in et cetera/etc. The word plus was in use to indicate addition since the early 1200s. It’s not clear that the ancient Romans used the word plus in the mathematical sense we have today, or indeed that they were ever nonplussed, but without Latin’s et we wouldn’t have the plus sign and without Latin we wouldn’t have nonplussed, so I’m concluding this is one the Romans Gave Us.

Irish readers – have any of you ever heard of namplush? I suspect it is archaic or very regional.

Until next time happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

January 10, 2022

Chaperon – How a Hat Word Saves Modesty

Hello,

This week’s word is chaperon and, as I sometimes discover, one I’ve been misspelling for a considerable number of years. Spelling it as chaperone is incorrect. Don’t argue with me, I have it from the Oxford English Dictionary “English writers often erroneously spell it chaperone, app. under the supposition that it requires a fem. termination”. No wriggling out of that one!

What exactly is a chaperon? A chaperon is a woman who accompanies a younger, unmarried lady in public. This could be her mother, aunt, even her maid servant, and the definition dates back to the 1700s. Clearly this rule didn’t apply to lower-class or working women who were too busy earning a crust, but a chaperon was vital for preserving the reputation and modesty of an upper-class lady, as without it she wouldn’t be able to marry well.

This requirement is no longer an issue in contemporary western society, thank goodness. Evolving social attitudes to male/female mixing, relationships, and morals have moved on from this restriction.

The word itself has older roots and is one the French gave us. English borrowed the word from French where a chaperon was a protector, especially a female protector of a young woman. In French it had an earlier meaning (around 1400) of a hood or head covering. It had been used in that way since at least Old French in the 1100s when it was a diminutive form of chape (which is related to capes and caps). It was also used in Middle English as a hooded cloak so it looks like both languages had that evolution of the idea of a head/body covering protecting you, to a person who protects you.

Head coverings were an important part of showing a woman’s modesty in English and French society at that time. You really wouldn’t appear in public without a head-wrap, turban, bonnet, kerchief etc. I’m not an expert on such things but it’s easy to see parallels with Catholic mantillas (now rarely worn except at the Vatican) and the hijab headscarves sometimes worn by Muslim women.

A jester’s chaperon

A jester’s chaperonThe chaperon head covering, like the word’s meaning, changed significantly over time. The original one in the early 1200s was a simple hood but over time extra layers and folds of fabric were added until a turban style head wrapping was achieved in the 1400s. Think of the sort of elaborate headgear a courtier might wear in Tudor times. They were worn as a sign of wealth and importance and were often made from large amounts of rich embroidered fabrics. Luckily the chaperon went out of style. I love hats but a chaperon would be a step too far for me.

Sometimes chaperons are used in ceremonial regalia at royal events or re-enactments. I’m sure I spotted some in Siena when hundreds of locals were preparing for their famous palio horse race by parading in medieval costume.

Happy New Year and until next time happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

January 3, 2022

Fufflement – Wrap up well in Winter

Hello,

It has been a mild winter here, so far. My walk this morning, however, leaned towards the chilly side. I shall have to deploy my Very Long Scarf soon. Inspired partly by Tom Baker’s Dr. Who scarf, I crocheted one in autumn shades and made it long enough to require looping around my neck several times. It’s made of merino wool and is very warm.

It reminded me of a dialect word I chanced upon one day on Twitter – fufflement. You probably won’t find it in your English dictionary, but it’s a good old word and seemed suitable for a day when you might want to wrap up in layers of winter clothing.

Fufflement is an old Yorkshire dialect word meaning “wearing too many layers of clothing”. Thanks to many years watching (and re-watching) episodes of “Friends” it always makes me think of the one when Joey dresses up in all of Chandler’s clothes to annoy him. He certainly wouldn’t have been cold today in that strange outfit. It can get pretty cold in the Yorkshire Dales during the winter, so I’m not surprised that’s where we get fufflement. The English spoken in Yorkshire often retains older words, I found that several times while researching Viking words. The next time I wind my Very Long Scarf around my neck, I shall know I am fuffling myself (or should that be fufflementing myself?), and I’ll think of the beautiful Yorkshire countryside.

I’ve previously investigated the history of kerfuffle, you can have a read of that here. Along the way to that one I discovered that the fuffle part dates back to the 1500s and was a Scottish verb meaning to disorder or dishevel. That ties in pretty well with Joey’s odd pile of clothes and my crazy scarf. It can get cold in Scotland too, although they might deploy a kilt for warmth, rather than my scarf looping approach.

Happy New Year and until next time happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

p.s. my Christmas book contest finished on the 31st of December. The winner was Roisin Tracey and her prize is on its way to her.