Zetta Elliott's Blog, page 39

February 23, 2016

Writing while Black/Writing while Indigenous: Part 2

Ambelin,

Just now as I came in, I heard a seagull cry outside my window and I was reminded, once again, that Brooklyn is on an island that faces the sea. I went for a walk this afternoon after mailing a book at the post office; next month I plan to self-publish the sequel to my time-travel novel A Wish After Midnight, and my most trusted reader-friend in Nova Scotia has agreed to provide a critique. There are so many of us separated by stretches of seawater yet when we find words for our experiences, the distance almost seems to disappear. One of the many books I have yet to write is The Hummingbird’s Tongue, an experimental memoir about migration, memory, and mental illness. I’ve tried to develop a structure for the book that reflects the fragmentation of an archipelago, which in turn symbolizes the fractures and ruptures caused by trauma. I’ve only given one talk on this memoir and found myself referencing a 1946 picture book I cherished as a child. In The Little Island by Golden MacDonald (Margaret Wise Brown), a kitten traps a fish but it wins its release by telling the kitten a secret: “All land is one land under the sea.” Weary as I am these days, I draw strength from the knowledge that I have allies like you at the end of so many seas, which makes the isolation of being a Black feminist writer in the US a bit easier to bear.

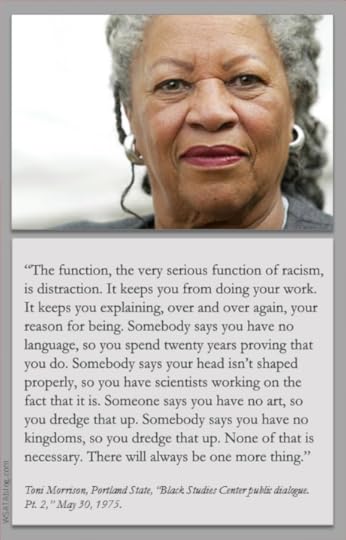

As I read your initial post I felt a strange blend of affirmation and sadness—too much of what you wrote was familiar to me, and I’m weary these days of the many challenges facing my own beleaguered community. Tired because the fight seems never-ending, and progress minimal. This nation—my adopted home—is on the brink of electing a brazen bigot, and his popularity reveals just how deeply racist the US continues to be. In the past year I’ve found myself actively withdrawing from spaces where I’m likely to encounter groups of whites (harder to do these days in my rapidly gentrifying neighborhood). When women of color friends become consumed with the latest outrageous behavior of white women writers, I simply shrug and keep on planning the publication of my novel. I began to self-publish because I had no other way to get my books into kids’ hands, but now being excluded from the publishing industry almost seems like a blessing. As I often like to say when tempests swirl in the kid lit cup, “That’s not my peer group.” I don’t have time to respond to all the ridiculous things oblivious white women say or do, and Toni Morrison’s wise words are never far from the front of my mind: “racism is a distraction.”

As I read your initial post I felt a strange blend of affirmation and sadness—too much of what you wrote was familiar to me, and I’m weary these days of the many challenges facing my own beleaguered community. Tired because the fight seems never-ending, and progress minimal. This nation—my adopted home—is on the brink of electing a brazen bigot, and his popularity reveals just how deeply racist the US continues to be. In the past year I’ve found myself actively withdrawing from spaces where I’m likely to encounter groups of whites (harder to do these days in my rapidly gentrifying neighborhood). When women of color friends become consumed with the latest outrageous behavior of white women writers, I simply shrug and keep on planning the publication of my novel. I began to self-publish because I had no other way to get my books into kids’ hands, but now being excluded from the publishing industry almost seems like a blessing. As I often like to say when tempests swirl in the kid lit cup, “That’s not my peer group.” I don’t have time to respond to all the ridiculous things oblivious white women say or do, and Toni Morrison’s wise words are never far from the front of my mind: “racism is a distraction.”

But it isn’t right that when a woman of color speaks her truth, countless white women feel entitled to attack her and believe they can do so with impunity—because, in fact, they can. Former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright recently warned, “There’s a special place in hell for women who don’t support other women.” If that’s true, then that special corner will be very crowded and mighty white. Yet afterlife aside, there never seems to be any penalty for the egregious behavior of those in the dominant group, and those with power and privilege routinely insist upon occupying the victim position even as they deny their role as victimizer. The recent Diversity Baseline Survey conducted by Lee & Low Books makes evident what many of us have known for years: white women dominate the kid lit community. So my separatist impulse is often thwarted by the fact that in order to reach the children of color I write about, I generally have to negotiate with an editor, librarian, reviewer, teacher, or literacy advocate who is likely to be a straight, white, middle-class cis woman. She is not from my community and likely got her job without needing to demonstrate basic competence in my culture. I do have radical white women friends who are actively anti-racist, but I can count them on one hand (and maybe two fingers). Their individual activism doesn’t change the fact that white women as a group are responsible for creating and/or sustaining the disparities we see in the kid lit community today. I very much appreciate true allies’ support and attempts at inclusion, but know that individual subversive acts will not change systems designed to promote and perpetuate dominance.

So how do we decolonize the kid lit community? How do we redistribute power and end the dominance of white women? As the topic of reparations resurfaces here in the US, I can’t help but wonder what reparations would look like within the kid lit community. How could the dominant group ever make amends for the damage done to our children? For decades here in the US they have ignored our pleas for inclusion and perpetrated a form of symbolic annihilation by distorting or altogether erasing the image of Black youth. Can the publishing industry really be trusted to reform itself when those who uphold it haven’t acknowledged the harm they’ve caused? Of course, the first step would be an admission of wrongdoing, but most white Americans prefer reconciliation without its prerequisite: TRUTH.

So how do we decolonize the kid lit community? How do we redistribute power and end the dominance of white women? As the topic of reparations resurfaces here in the US, I can’t help but wonder what reparations would look like within the kid lit community. How could the dominant group ever make amends for the damage done to our children? For decades here in the US they have ignored our pleas for inclusion and perpetrated a form of symbolic annihilation by distorting or altogether erasing the image of Black youth. Can the publishing industry really be trusted to reform itself when those who uphold it haven’t acknowledged the harm they’ve caused? Of course, the first step would be an admission of wrongdoing, but most white Americans prefer reconciliation without its prerequisite: TRUTH.

Author Libba Bray attempted to reason with her white peers and cited a reading by Toni Morrison that she attended here in Brooklyn. Bray recounts that when Morrison was asked what her female characters had taught her, she replied, “Sovereignty.” I imagine that word holds particular resonance for Indigenous people. For me, self-publishing is the only way I will ever retain control over my words and my message to our youth. And I love our youth enough to tell them the unfiltered truth about life in this country. Of course, there are penalties for women of color who dare to create as a radical act of love. As John Henrik Clarke once stated,

Racists will always call you a racist when you identify their racism. To love yourself now – is a form of racism. We are the only people who are criticized for loving ourselves, and white people think when you love yourself you hate them. No, when I love myself they become irrelevant to me.

Apparently Canadians are preparing an island for those in the US looking to migrate after Trump’s election. But I left Canada once already and know there is no island sanctuary for a Black feminist writer like me. What keeps me afloat is the work and the knowledge that there are allies like you in the world. Thank you for persisting, for claiming space, and loving your youth. The sea between us may seem endless, but under the waves there is land that unites us.

This post is part of a series of essays, letters, and reflections shared by Ambelin Kwaymullina and Zetta Elliott. Read Part 1 here.

February 22, 2016

Writing while Black/writing while Indigenous: two voices speak on literature, representation and justice

Ambelin Kwaymullina and I met online a couple of years ago and found that we share similar perspectives on issues of representation in children’s and young adult literature. When I told Ambelin I wanted to write something about “Black excellence,” she proposed a series of posts where we could reflect on “the diversity debate” and the ways current responses dismiss or altogether ignore the needs of kids in our communities. Welcome, Ambelin!

Ambelin Kwaymullina and I met online a couple of years ago and found that we share similar perspectives on issues of representation in children’s and young adult literature. When I told Ambelin I wanted to write something about “Black excellence,” she proposed a series of posts where we could reflect on “the diversity debate” and the ways current responses dismiss or altogether ignore the needs of kids in our communities. Welcome, Ambelin!

***

I am an Aboriginal woman who comes from the Palyku people of the Pilbara region of Western Australia. I write YA novels and picture books, and I teach law at a university. I’m often told that being a writer and a law academic is a strange combination, but there is a powerful connection between law and storytelling. The global seizure of Indigenous territories by colonial nation-states has long been justified by legal doctrines based in derogatory stories told about Indigenous peoples. In Australia this was terra nullius, the notion that Indigenous peoples did not own the land we occupied because we were not sufficiently ‘advanced’ (which is to say, our life-ways and law-ways did not resemble those of Western Europe). And in Australia and elsewhere, stories continue to influence the way in which Indigenous and other marginalised peoples are treated by the law.

When I began my law degree I had a deep-seated fear of those in a position of public authority, inherited from my ancestors who survived the ‘protection’ era. From the late 1800s onward in Australia, so-called ‘protection’ legislation authorised the forcible removal of Indigenous children from their families. It is estimated that from 1910 to 1970, between one in three and one in ten children were taken. In some families, all the children were taken. In other families the removal and institutionalisation of children occurred over successive generations. My great-grandmother and my grandmother were among them; they belong to what is now called the Stolen Generations. ‘Protection’ legislation was also the basis of a system of intensive surveillance and control under which no aspect of Indigenous existence escaped the attention of government officers.

The last remnants of the ‘protection’ regime were dismantled in the 1970s and Australia enacted national racial discrimination legislation in 1975. My law degree gives me the training to locate and interpret the guarantees of equality that now exist. I once imagined that this would be empowering. Yet it has not made me less afraid. If anything I am more so, because if I know the power of the law then I also understand its limits. Law can regulate behavior; it is often far less successful at changing attitudes. But attitudes can subvert the law and make a mockery of notions of equal treatment and equal opportunity. A recent report on racial discrimination legislation in Australia highlighted the persistence of systemic discrimination against Indigenous peoples. Health research has shown that Indigenous Australians are one-third less likely to receive appropriate medical care than non-Indigenous patients with the same need. Beyond Blue’s recent study of Australians aged 25 – 44 found that one in five would move away if an Indigenous person sat near them, one in ten would not hire an Indigenous person, and one in five believe it is hard to treat Indigenous Australians in the same way as everybody else. Statistics in relation to Indigenous peoples elsewhere will differ in their details but the larger trends repeat – as was found by the United Nations State of the World’s Indigenous Peoples report, Indigenous peoples across the globe face systemic discrimination and exclusion from political and economic power.

Behind all these statistics are the stories. There are thousands upon thousands of stories that distort the identities, cultures and histories of the many Indigenous peoples of the earth. These stories influence other tales in a self-perpetuating cycle supported by the structures of privilege that continue to exclude Indigenous voices from speaking to our own truths. Representation – or rather misrepresentation – in narrative is not separate from discrimination; it is part of what enables it. In those crucial moments when others are making choices that will influence our fate, it is the stories they know about us that alter perception and displace empathy. When diverse authors say that diversity in literature is a matter of life and death, I think some people believe we are using hyperbole. But the grim truth is that the marginalised have no need of hyperbole to make our point. We only need reality.

Behind all these statistics are the stories. There are thousands upon thousands of stories that distort the identities, cultures and histories of the many Indigenous peoples of the earth. These stories influence other tales in a self-perpetuating cycle supported by the structures of privilege that continue to exclude Indigenous voices from speaking to our own truths. Representation – or rather misrepresentation – in narrative is not separate from discrimination; it is part of what enables it. In those crucial moments when others are making choices that will influence our fate, it is the stories they know about us that alter perception and displace empathy. When diverse authors say that diversity in literature is a matter of life and death, I think some people believe we are using hyperbole. But the grim truth is that the marginalised have no need of hyperbole to make our point. We only need reality.

There are those who study the law because they love the law; I studied the law in search of justice. In the legal systems of the many Aboriginal nations of Australia, there is a strong correlation between the concept of justice and that of balance. Far less so, in Western legal systems. Less so too in the world of literature where there are massive imbalances in power between the privileged and the marginalised. But I am not the only one who would name this imbalance unjust, because I am one of many voices across the globe speaking to these issues. Some of us come from the peoples that have been, and are being, excluded; from a history of voices silenced and stories never told. Some are among the privileged who have inherited the benefits of our exclusion. But we are all part of a future that has not yet been fathomed.

None of us know what the world of literature looks like when all voices are heard equally and all voices have an equal opportunity to be heard. Such a world doesn’t exist. But I think I see it sometimes, or rather I feel it. The sound of a thousand peoples speaking to a thousand different realities. A sense of there being air enough for everyone to breathe. Daniel Older has said that “perhaps the word hasn’t been invented yet [for] that thing beyond diversity.”

I call it justice.

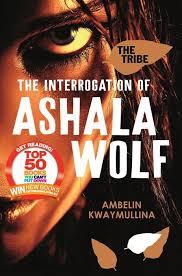

Ambelin Kwaymullina is an Aboriginal writer, illustrator and law academic who comes from the Palyku (pronounced ‘Bailgu’) people of the Pilbara region of Western Australia. She is the author of the Tribe series, a dystopian trilogy for young adults, the first book of which (The Interrogation of Ashala Wolf) is published in the US. She has also written and illustrated a number of picture books. Some of Ambelin’s commentary on diversity issues can be found here.

February 20, 2016

Electric Avenue

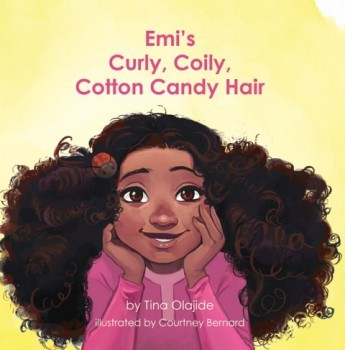

Between jet lag and this never-ending cold, I haven’t gotten a lot of sleep this past week. But my four days in London produced nearly 4000 words so I’ve still managed to be productive, and stepping outside of my Brooklyn life helped me to shift my focus from The Door at the Crossroads to The Ghosts in the Castle. On Monday I arrived with a migraine but checked into my lovely hotel and an hour later went over to Hammersmith to meet another indie author, Tina Olajide. The first book in her Hey Emi series is very popular here in the US, and we talked about ways to expand access to libraries and schools. I learned of Tina through radical Oakland librarian Amy Martin who’s on a mission to add diverse titles to her youth collection by connecting with indie authors. I wish there were more librarians like her! Tina and I swapped stories about the self-publishing process until my energy ran out and I went back to the hotel. There’s something about being in a bubble that helps me write; I can produce here at home but when I’m abroad, there’s a

Between jet lag and this never-ending cold, I haven’t gotten a lot of sleep this past week. But my four days in London produced nearly 4000 words so I’ve still managed to be productive, and stepping outside of my Brooklyn life helped me to shift my focus from The Door at the Crossroads to The Ghosts in the Castle. On Monday I arrived with a migraine but checked into my lovely hotel and an hour later went over to Hammersmith to meet another indie author, Tina Olajide. The first book in her Hey Emi series is very popular here in the US, and we talked about ways to expand access to libraries and schools. I learned of Tina through radical Oakland librarian Amy Martin who’s on a mission to add diverse titles to her youth collection by connecting with indie authors. I wish there were more librarians like her! Tina and I swapped stories about the self-publishing process until my energy ran out and I went back to the hotel. There’s something about being in a bubble that helps me write; I can produce here at home but when I’m abroad, there’s a  greater sense of urgency. I knew I only had 4 days, and I knew I wanted to see my former editor from Amazon, and I had to tour Windsor Castle once more, and I was invited to tea with a dear friend, her daughter, and granddaughter. I actually might write Brown’s Hotel into my book since I conclude with a tea party between Zaria and her stern Aunt Prudence. In so many of the British books I read as a child, the eccentric aunt takes an interest in—and leaves her fortune to—her most unlikely heir. But instead of passing on her fortune, Aunt Prudence will share her memories of the 1981 Brixton Riots. I spent a couple of hours in Brixton before heading to

greater sense of urgency. I knew I only had 4 days, and I knew I wanted to see my former editor from Amazon, and I had to tour Windsor Castle once more, and I was invited to tea with a dear friend, her daughter, and granddaughter. I actually might write Brown’s Hotel into my book since I conclude with a tea party between Zaria and her stern Aunt Prudence. In so many of the British books I read as a child, the eccentric aunt takes an interest in—and leaves her fortune to—her most unlikely heir. But instead of passing on her fortune, Aunt Prudence will share her memories of the 1981 Brixton Riots. I spent a couple of hours in Brixton before heading to  the airport on Thursday. I found a downloadable walking tour map online and picked out the marketplaces since I needed a shop or vendor where the two children might buy an Ethiopian necklace. After browsing a bit and talking to an Algerian vendor about gentrification in Brixton and Brooklyn, I went to the Black Cultural Archives for lunch. The kitchen was closed but I wrote for a while and chatted with two women there who pointed me in the direction of an Ethiopian shop where I got a necklace and scarf. The Ethiopian woman running the shop and a nearby cafe hadn’t heard of Prince Alemayehu (pictured above), and I wondered if The Ghosts in the Castle would ever circulate in the UK. There are two protagonists, one Black British boy and his African American cousin, but it’s her outsider perspective that drives the narrative. Zaria comes to England as I did for the first time over 20 years ago, with a head full of stories about British castles and wizards and fairies. What she learns at age 8 is what I didn’t learn until my 20s: that British imperialism devastated the countries and cultures of people of color all over the world.

the airport on Thursday. I found a downloadable walking tour map online and picked out the marketplaces since I needed a shop or vendor where the two children might buy an Ethiopian necklace. After browsing a bit and talking to an Algerian vendor about gentrification in Brixton and Brooklyn, I went to the Black Cultural Archives for lunch. The kitchen was closed but I wrote for a while and chatted with two women there who pointed me in the direction of an Ethiopian shop where I got a necklace and scarf. The Ethiopian woman running the shop and a nearby cafe hadn’t heard of Prince Alemayehu (pictured above), and I wondered if The Ghosts in the Castle would ever circulate in the UK. There are two protagonists, one Black British boy and his African American cousin, but it’s her outsider perspective that drives the narrative. Zaria comes to England as I did for the first time over 20 years ago, with a head full of stories about British castles and wizards and fairies. What she learns at age 8 is what I didn’t learn until my 20s: that British imperialism devastated the countries and cultures of people of color all over the world.

On Monday I’ll have a guest blogger, Ambelin Kwaymullina. We’re doing a series of blog posts starting next week about decolonizing kid lit so stay tuned…

February 10, 2016

#DearScholastic

Do you remember buying books from the Scholastic Book Fair? I think I do. You got a little catalog at school, and you picked the book you wanted, and then brought in your order slip with your money. Well, Scholastic Book Fair is still going strong but I hear from more and more teachers that they don’t want the fair in their school. The books aren’t diverse and kids often buy licensed products instead of books—so how does that promote literacy? I was at a school last month and a 5th grade teacher surveyed my 20 books and asked, “Will these be available at our Scholastic Book Fair next week?” No—they won’t. Your Black and Latino students will probably be hard-pressed to find a “mirror book” in Scholastic’s offerings.

Last year I met a fantastic 3rd grade teacher, Ruben Brosbe, and his students have started a letter-writing campaign to get Scholastic to diversify their book fair offerings:

Last year I met a fantastic 3rd grade teacher, Ruben Brosbe, and his students have started a letter-writing campaign to get Scholastic to diversify their book fair offerings:

Dear Scholastic Books,

In the fall my students learned about the diversity gap in children’s literature. When the December Scholastic Book Club catalog arrived, we decided to count the number of books featuring people of color. Out of more than 100 books we counted about 7 that had people of color.

We decided to write you letters to tell you how we felt about this.

Thanks for reading! We hope you will write back!

Sincerely,

Mr. Ruben and Class 301

Here’s one excerpt from a letter by Maya:

“When diverse kids have to read books with only white characters it makes them feel left out. It makes them feel like white kids are better. Our class counted and out of over one hundred books less than ten are diverse. I don’t think that’s fair. Also white kids want to read about different types of people. It’s never different types of people.”

All the letters are powerful so please take the time to read, and retweet, and follow their campaign: @diversereaders #DearScholastic

February 4, 2016

reflecting on representation

At the end of every year, Edith Campbell and I compile a list of middle grade and young adult novels authored by African Americans. Our 2015 list was particularly demoralizing, with only 32 of 3,000 novels for young readers published by Black writers (and only 2 debut authors). Lee & Low’s Diversity Baseline Survey proves what many of us have known for years: white women run the publishing industry. Can we trust these gatekeepers to find the stories that fully and accurately reflect “the Black experience?” With so few books published annually, can we truly achieve excellence in African American children’s literature? This year Edi and I decided to reflect on these lists and what they tell us about the status of African American writers in the children’s publishing industry.

At the end of every year, Edith Campbell and I compile a list of middle grade and young adult novels authored by African Americans. Our 2015 list was particularly demoralizing, with only 32 of 3,000 novels for young readers published by Black writers (and only 2 debut authors). Lee & Low’s Diversity Baseline Survey proves what many of us have known for years: white women run the publishing industry. Can we trust these gatekeepers to find the stories that fully and accurately reflect “the Black experience?” With so few books published annually, can we truly achieve excellence in African American children’s literature? This year Edi and I decided to reflect on these lists and what they tell us about the status of African American writers in the children’s publishing industry.

Zetta: Many people thank me for posting our annual African American MG/YA novel list, but I source the titles from your blog. When and why did you start keeping track of new releases by PoC/First Nations authors, and what compelled you to count debut authors?

Edi: This question made me go back to the early days of my blog and see what I could find about the beginnings of my book lists. On a post a few months after I began the blog, I mentioned that I was creating a book list for urban teens and that I would begin looking for books for Latino students soon. That first list was (and is) a mess. It contained every book I could think of regardless of when it was published. Every year, my list becomes more polished and more diverse. At some point, I decided to promote all Native American and authors of color and to post new books each month. I know that we’ve used my lists to locate Latinx books and African American speculative fiction. I’ve used it to locate books with African American female lead characters. I’m not sure if anyone else is using the lists as data, but they certainly could.

I think it’s important to take note of new authors. If that first book doesn’t sell as projected, their career is in jeopardy. So I create that list to start bringing attention to the debut authors. I’m not on a selection committee this year, so I’ll be able to interview them and review their books unlike last year. I’ve not paid a lot of attention to the ethnic breakdown of the debut authors list because, like it or not, all brown folk face the same basic discrimination in publishing. I do believe, however, that this year there are only 2 African American debut authors in a list of twenty, and they’re both female.

Edi: Are you ever surprised by what these lists of African American MG/YA fiction titles reveal?

Zetta: No, I’m never surprised. People want to believe we’re making “progress” because the word “diversity” gets bandied about on social media. But what’s needed in the “movement” for inclusive children’s literature is greater transparency. I get VERY tired of the relentless optimism and naïveté of some diversity advocates who refuse to grapple with the facts. If there are 3000 novels published for young readers in the US each year, then should we really be celebrating the publication of 30 Black-authored novels? And of those 30 authors, only TWO were making their debut in 2015? I think that’s appalling. I want our lists to put things in perspective, but I find people often use them in other ways—and that’s okay. My primary goal, however, is to reveal what’s really going on in children’s publishing here in the US. It always reminds me of that quote by Malcolm X about progress:

“If you stick a knife in my back nine inches and pull it out six inches, there’s not progress. If you pull it all the way out that’s not progress. Progress is healing the wound that the blow made. And they haven’t even pulled the knife out much less heal the wound. They won’t even admit the knife is there.”

We’ll never resolve the diversity disparities in children’s publishing if we don’t first acknowledge the severity of the problem. And that includes holding people accountable. Imagine what would happen if WNDB took to Twitter and asked their 20K followers to join them in demanding that the Big 5 each debut FIVE Black authors per year for the next 5 years. To quote another important Black male activist, “Power concedes nothing without a demand.” I’m still waiting for WNDB to demand SOMETHING, anything from the publishing industry. They have so much power and it seems they’re using it to uphold the status quo.

Zetta: You’re involved with WNDB. Describe your role and the impact you feel this young movement will have on racial disparities in kid lit.

Edi: My only formal connection to WNDB was being on the selection committee for the initial Walter Award. I think impact can only be measured in retrospect, and I would like to see it done on WNDB’s terms. I’m hoping they have measurable goals that will be clear indications of their success. I think WNDB developed at a time when awareness of marginalization was growing across industries, and the time was ripe for them to build an audience. From a variety of things I’m seeing, I do feel that diversity is not going away any time soon and I think that’s because WNDB has legitimized its presence in kidlit. At the same time, I think marginalization in kidlt (ha! in America) is so pervasive that it will take constant and consistent efforts on many fronts to change what’s being put in front of our children. Some of this is about economics, but it’s also about access to our children.

Edi: A lot has happened with regards to diversity in kidlit. What gives you hope that things are going to change, that there will be better representation for marginalized youth?

Zetta: Did I miss something? What has happened exactly? In what way has the status quo changed? I’m not optimistic, I’m afraid. Lee & Low’s Diversity Baseline Survey proves to the world what many of us have known for a long time: white, straight, middle-class cis women run this industry. Will they have a sudden epiphany, recognize the error of their ways, and vow to correct the disparities they’ve created? I doubt it. The publishing industry wasn’t designed to serve our children or our communities. The people who work in publishing, for the most part, are not from our communities. I advocate for a community-based publishing model that will empower marginalized people and turn them into consumers and producers of books. A public library in St. Paul, MN published books for speakers of Karen in their community—that gives me hope. A traditional publisher would argue that catering to such a small population wouldn’t make commercial sense, but imagine what it means to the members of that community to have books in their own language! What gives me hope is the impulse to make books for reasons OTHER than profit. Tell your story because it proves you believe your voice matters. Tell your story so that it can counter the dominant narrative. Tell your story because expressing yourself is good for you! Tell your story because if you don’t, someone else will. More than half of the children’s books about Blacks that were published in 2014 were written by whites. That’s not ok. Print-on-demand technology makes it possible for more and more people to tell their stories, their way—without interference from culturally incompetent gatekeepers. THAT gives me hope!

February 2, 2016

“find your own voice & use it”

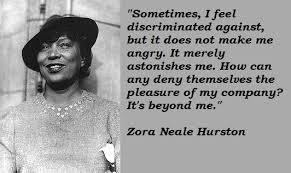

I’ve had two opportunities to have my say recently. Last summer an editor at Publishers Weekly asked me to participate in a panel of “indie experts” but I declined because I didn’t feel I had enough expertise. The editor kindly suggested I write an article for him instead and it took me six months, but I finally got it done before Xmas. It went up yesterday; “How It Feels to Be Self-Published Me” was inspired by Zora Neale Hurston’s 1928 essay “How It Feels to Be Colored Me.” I had to cut about a third of it but I think my message comes through loud and clear, and it seems to be resonating with lots of folks online:

I’ve had two opportunities to have my say recently. Last summer an editor at Publishers Weekly asked me to participate in a panel of “indie experts” but I declined because I didn’t feel I had enough expertise. The editor kindly suggested I write an article for him instead and it took me six months, but I finally got it done before Xmas. It went up yesterday; “How It Feels to Be Self-Published Me” was inspired by Zora Neale Hurston’s 1928 essay “How It Feels to Be Colored Me.” I had to cut about a third of it but I think my message comes through loud and clear, and it seems to be resonating with lots of folks online:

Like Hurston, I remember the moment I went from being an admired, multi-award-winning debut picture book author to a largely unknown, ignored, and even pitied self-published author. In the past two years I have published sixteen books for young readers, but my books are not eligible for review in the major outlets, public libraries refuse to acquire them for their collections, and major awards are no longer a possibility. Despite the many voices clamoring for books that better reflect the nation’s diverse population, my indie titles that center on marginalized children are summarily dismissed. And there is little I can do about this marginalization; there are no penalties when gatekeepers reject books simply because they don’t come from a system that’s rigged against writers of color. So have I really found the success I deserve?

On Sunday I had the honor of being featured on Dr. Ebony Thomas’ blog The Dark Fantastic. Ebony is a professor in the Graduate School of Education at the University of Pennsylvania, and with her graduate students she has compiled a list of children’s books that promote social justice (#Kidlit4Justice). Her grad students also came up with some thought-provoking questions:

5) A notable contingent of tweeters for #kidlit4justice have asked the twitter sphere to donate both money and books to libraries. What role have libraries paid in fighting for justice in the past, and does a similar role exist for libraries today or in future fights for justice?

I grew up depending on libraries. My family didn’t have much money and we had no tradition of buying new books, but we all had library cards. The only diverse books in my library’s collection, however, were the ones that managed to win an award—like Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry. I think the field of library science needs to evolve and diversify so that collections do the same. The kid lit community in general is dominated by middle-class white women—they make up the majority of editors, reviewers, librarians, teachers—and they need to ask themselves what they’ve done and/or are doing to perpetuate racial disparities. Citizens also need to let their elected officials know that library funding is important, especially since public libraries do so much more now than just circulate books. The Brooklyn Public Library has sponsored my author visits for years, and through them I’ve reached hundreds of kids. But the BPL won’t acquire self-published books, so that leaves the vast majority of my books out of reach for kids who rely on the library. The BPL has asked me to develop a workshop on self-publishing and I think that’s the way forward—I believe in community–based publishing and think libraries should take the lead in developing producers of books, not just consumers.

I concluded my PW essay with a line from one of Jayne Cortez’ poems, “Find Your Own Voice.” We should all follow her advice! I’m grateful for the chance to share my point of view, and for everyone who took the time to read and respond. Every time we speak up for ourselves, we build community…

January 30, 2016

#1000BlackGirlBooks

Yesterday I had the opportunity to discuss diverse books with Lee & Low publisher Jason Low on The Brian Lehrer Show. I was invited to talk about Marley Dias’ remarkable book drive to gather 1000 books that feature Black girls. Friends on Facebook have been posting this story on my page for weeks, and a few days ago I finally packed up some of my books and mailed them off (if you’d like to donate, too, here’s the address: GrassROOTS Community Foundation, 59 Main Street, Suite 323, West Orange, NJ 07052). Jason was invited to share the results of Lee & Low’s Diversity Baseline Survey, which were released last week (see below). I had SO much to say about the need for “mirror books” and the problem with white women dominating the publishing industry, but we only had time to make a couple of remarks each before the host invited listeners to call in with their book recommendations. I’ve written elsewhere about my experiences with white women (see “sister/outsider” and “unmanageable me“), and this survey didn’t reveal anything I didn’t already know. But it’s important to have this graphic because it makes their dominance VISIBLE. When I say, “White women should be held accountable for the disparities in children’s literature,” some people (mostly white) think I’m being unfair. But the data prove that white women run this industry—and they make up the majority of teachers, librarians, booksellers, and nonprofit literacy advocates. So if the books Marley needs don’t exist or aren’t showing up in her classroom, who’s to blame?

Yesterday I had the opportunity to discuss diverse books with Lee & Low publisher Jason Low on The Brian Lehrer Show. I was invited to talk about Marley Dias’ remarkable book drive to gather 1000 books that feature Black girls. Friends on Facebook have been posting this story on my page for weeks, and a few days ago I finally packed up some of my books and mailed them off (if you’d like to donate, too, here’s the address: GrassROOTS Community Foundation, 59 Main Street, Suite 323, West Orange, NJ 07052). Jason was invited to share the results of Lee & Low’s Diversity Baseline Survey, which were released last week (see below). I had SO much to say about the need for “mirror books” and the problem with white women dominating the publishing industry, but we only had time to make a couple of remarks each before the host invited listeners to call in with their book recommendations. I’ve written elsewhere about my experiences with white women (see “sister/outsider” and “unmanageable me“), and this survey didn’t reveal anything I didn’t already know. But it’s important to have this graphic because it makes their dominance VISIBLE. When I say, “White women should be held accountable for the disparities in children’s literature,” some people (mostly white) think I’m being unfair. But the data prove that white women run this industry—and they make up the majority of teachers, librarians, booksellers, and nonprofit literacy advocates. So if the books Marley needs don’t exist or aren’t showing up in her classroom, who’s to blame?

January 25, 2016

Multicultural Children’s Book Day

January 27th is Multicultural Children’s Book Day! Join @MCChildsBookDay at 9pm EST for the MCCBD Twitter Party! Parents, teachers and librarians who register to come to our twitter party will have the chance to follow the #ReadYourWorld conversation and win one of 12 5-book bundles plus one grand prize bundle. Details are here.

January 24, 2016

be a witness

One of the best pieces of advice I ever received came from my graduate school advisor. She was teaching a seminar on Black popular culture and several first-year Black male students came to class every week ready for a fight. Now that I’ve taught at the college level for close to ten years, I realize those young men were probably trying to challenge my Black woman professor’s authority. She always let them have their say before showing them the error of their ways, but I remember walking out of the room one day when I’d had enough of their foolishness. Later she told me I needed to stay in the room. “Be a witness,” is what I remember her telling me. “And be strategic. You can’t reason with every idiot.”

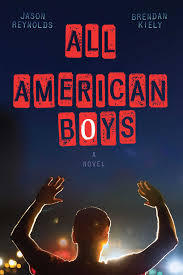

I’ve applied that advice over the years, learning when its best to hold my tongue and when I need to jump into the fray. I often think of Toni Morrison’s reminder that racism is a distraction, and so I try to focus on getting my work done instead of chastising white folks every time they mess up. When it comes to men of color and sexism, I generally reserve my remarks for my private conversations with other women of color; we know there are consequences that come with criticizing “our men” in public but when we’re together, we can talk about how it feels when white women editors, educators, and librarians knock us down in their haste to get next to the one straight male author of color in the room. In our own company, we’re able to safely discuss “misogynoir“—the very real discrimination we face as Black women writers in an industry that’s dominated by white women gatekeepers. When I wrote my critique of All American Boys last week, I focused on what was missing from the book: the agency and voices of young Black women. I thought about that provocative video project “Every Single Word,” where you only hear the lines spoken by people of color in major motion pictures. If we did something similar for All American Boys, what would we hear from girls of color on the topic of police brutality? Not much. I emailed Jason Reynolds when the post went up, and yesterday he took the time to write this response:

I’ve applied that advice over the years, learning when its best to hold my tongue and when I need to jump into the fray. I often think of Toni Morrison’s reminder that racism is a distraction, and so I try to focus on getting my work done instead of chastising white folks every time they mess up. When it comes to men of color and sexism, I generally reserve my remarks for my private conversations with other women of color; we know there are consequences that come with criticizing “our men” in public but when we’re together, we can talk about how it feels when white women editors, educators, and librarians knock us down in their haste to get next to the one straight male author of color in the room. In our own company, we’re able to safely discuss “misogynoir“—the very real discrimination we face as Black women writers in an industry that’s dominated by white women gatekeepers. When I wrote my critique of All American Boys last week, I focused on what was missing from the book: the agency and voices of young Black women. I thought about that provocative video project “Every Single Word,” where you only hear the lines spoken by people of color in major motion pictures. If we did something similar for All American Boys, what would we hear from girls of color on the topic of police brutality? Not much. I emailed Jason Reynolds when the post went up, and yesterday he took the time to write this response:

Zetta, thank you for this post. As one of the writers of All American Boys, I don’t necessarily feel any need to offer a rebuttal. I have no reason to be defensive. The points you raise are spot on, and they are, in fact, things I’d thought about in the process of making this book. I even had a hard time with the title for this very reason. My hope was that Tiffany, who worked closely with Jill, would sing out more prominently as part of the planning of the protest, but while focusing on the story of Rashad and approaching it from his first person narrative, it didn’t come across as such. And for that, I’m accountable. I own that. I felt similarly about Berry. *You* see her as a young woman who is doing what her boyfriend tells her, and doesn’t know about her little brother’s experience’s with the cops. *I* saw her as a powerful character, smarter than everyone else in the story, working hard to make change in the community. I saw her as a blazer. As someone whose “role” was at the *front* of the line — the only singular voice heard at the protest. She was the leader. But we were in Rashad’s head, in his family, in his vacuum, so all the information is being disseminated through his closest of kin, his brother. But maybe Rashad should’ve had a sister. Reading your post makes it clear that Berry doesn’t come across as I’d hoped. And that’s frustrating. The hard part about writing a book like this (for me) was knowing that there was no way I was going to hit all the marks. And admittedly, I didn’t. But it wasn’t a blind, ignorant scribble (not that you said it was.) I recognize fully how important it is to do away with the erasure of black girls and women, and I truly appreciate the call-out. And you have my word, I’ll continue to try to do better.

All the love.

People on Facebook and Twitter are praising our civil, reasoned exchange, and I understand why. Too often when an author gets called out, s/he responds with defensive vitriol. It’s clear from his response that Jason had a different narrative unfolding in his head, to which I would say: “If you need a Black feminist beta reader, let me know.” Because whenever a problematic book comes out, it points to a failure of process. Writing is a solitary activity, but publishing a book is not. It would have been great if the editor of this novel thought about the exclusion of Black girls. It would have meant a lot to me if some reviewers gave the book the praise it deserves but also pointed out this particular limitation. The fact that neither of those things happened confirms for me that a lot of people in the kid lit community aren’t really thinking about Black girls. I don’t generally review books but I published my critique on my blog because I was trying to be strategic. I’ve only met Jason once, but he seemed like an open-minded person and the comment he left on my blog proves that to be true. I also heard he has a ten-book deal, which means he’ll have plenty of opportunities to write (better) Black female characters in the future. Will reviewers and librarians and editors educate themselves about intersectionality and misogynoir? I doubt it. And that puts the onus on the writer—WE have to work harder because we can’t rely on others in the publishing process to get it right. No writer is perfect—I make mistakes all the time. But I care about Black youth and I know Jason does, too. And that’s why we have to help and look out for one another.

This would make a great panel, don’t you think?

January 19, 2016

nobody’s cheerleader

A feminist friend of mine once shared with me that her eldest daughter was trying out for the cheerleading squad at her school. I understood her concerns, but pointed out that cheerleading can be quite athletic and there are competitions that have nothing to do with girls in miniskirts waving pompoms to encourage boys as they run up and down the basketball court or football field. In the end she decided to compromise; her daughter could try out for cheerleading so long as she also picked some extra-curricular activities that developed her intellectual abilities (I think her daughter opted for student government).

A feminist friend of mine once shared with me that her eldest daughter was trying out for the cheerleading squad at her school. I understood her concerns, but pointed out that cheerleading can be quite athletic and there are competitions that have nothing to do with girls in miniskirts waving pompoms to encourage boys as they run up and down the basketball court or football field. In the end she decided to compromise; her daughter could try out for cheerleading so long as she also picked some extra-curricular activities that developed her intellectual abilities (I think her daughter opted for student government).

I used to say with pride, “I’m nobody’s cheerleader.” As a young Black feminist, I refused to engage in any activity that seemed designed to subordinate women in order to uplift men. Skimpy outfits aside, it’s frustrating to know that squads of boys/men never show up to cheer on women athletes. There’s no reciprocity—it’s all about celebrating male achievement. Yet as a teacher, I found that it often *was* my job to cheer from the sidelines as my students struggled to apply the lessons they learned from me in class. And there wasn’t much reciprocity because even though I could (and did) learn from my students, there was a built-in imbalance since I was being paid to serve them and not the other way around. I want *all* of my students to achieve but over the course of 25 years, I have gotten so used to purposely cheering on bright Black boys that I sometimes have to remind myself to give equal time to Black girls. Experience has taught me to expect Black girls to succeed (because they generally do) whereas experience has taught me that many Black boys struggle and will give up without extra encouragement. Yesterday was MLK Day and I went up to White Plains to present at a fundraiser for the MLK Freedom Library. It was a wonderful group that broke down in the usual way—several Black (grand)mothers with their kids, just one or two Black (grand)fathers with their kids, and quite a few older and younger Black women who came out (I think) to support their sorority, which co-sponsored the event. There was a Black boy sitting in the front who kept raising his hand to share personal anecdotes; sometimes I listened long enough to connect his comments to my presentation and other times I asked him to save his question or comment until the end. When I asked for a volunteer to read a passage on one of the slides, he waved his hand in the air and stood by the screen as soon as I called on him. I warned him that there were some big words in the passage but I would help him if he got stuck. Then I discovered that he could only read words with 2 or 3 letters, which meant that we read most of the passage together. But he kept his eyes on me and I knew the entire audience was cheering him on, and we all gave him a round of applause once he reached the end. Would a Black girl with limited reading skills wave her hand and ask to read aloud? I don’t know. Would the primarily female audience have gotten behind her in the same way? I hope so.

Black women are desperate to see Black boys succeed. We’re keenly aware of the many arenas where Black men are nowhere to be found; we feel their absence, mourn it, and generally do what we can to support the Black men who seem to be beating the odds. But it’s not easy being a Black feminist when there’s almost zero reciprocity, and standing up for Black girls can lead to charges of disloyalty to “the race.” Folks are worried that Will Smith and Michael B. Jordan weren’t nominated for an Oscar. I haven’t heard anyone mention that no Black women were nominated either, though I suppose that might be due to the fact that Black women are finally taking up space in television. Yesterday on the train ride back from White Plains I had an excellent conversation with two sorors I met at the event; we talked about politics and pop culture, the Black intellectuals we admire or can’t stand. We parted ways at Grand Central and on the subway back to Brooklyn I finished reading All American Boys. It’s an important book, I’m glad it exists. I’ve read all of Jason Reynold’s books and went into this one worried he’d give short shrift to Black girls—and I wasn’t disappointed. Despite giving a shout out in the acknowledgments section to women who are regularly rendered invisible in civil rights movements, no teenage Black girl has a voice or a significant role in the book. Black girls are the objects of desire for the book’s Black male characters—they’re there to “get all up on” and/or serve as props for teasing other boys. Considering the fact that young queer Black women FOUNDED the Black Lives Matter movement, it was disappointing to have a WHITE girl (written by the book’s white co-author, Brendan Kiely) be the one to introduce (at the end of the book). Black female victims of police brutality are named at the protest, but the one young Black woman with potential—Berry, a law student—is totally ignorant of her younger brother’s history with the police, and at the protest merely reads the script handed to her by her Black male boyfriend (and brother of the protagonist/victim). Imagine how different the book would be if instead of an older brother, Rashad had had an older sister—and she and her girlfriend organized the rally. Imagine if Tiffany, the girl Rashad hoped to “rub-a-dub on,” had been given a voice and an opportunity to talk about how police brutality impacted her life, her community, her personal sense of safety (think convicted rapist cop Daniel Holtzclaw and #BlackWomenMatter).

Black women are desperate to see Black boys succeed. We’re keenly aware of the many arenas where Black men are nowhere to be found; we feel their absence, mourn it, and generally do what we can to support the Black men who seem to be beating the odds. But it’s not easy being a Black feminist when there’s almost zero reciprocity, and standing up for Black girls can lead to charges of disloyalty to “the race.” Folks are worried that Will Smith and Michael B. Jordan weren’t nominated for an Oscar. I haven’t heard anyone mention that no Black women were nominated either, though I suppose that might be due to the fact that Black women are finally taking up space in television. Yesterday on the train ride back from White Plains I had an excellent conversation with two sorors I met at the event; we talked about politics and pop culture, the Black intellectuals we admire or can’t stand. We parted ways at Grand Central and on the subway back to Brooklyn I finished reading All American Boys. It’s an important book, I’m glad it exists. I’ve read all of Jason Reynold’s books and went into this one worried he’d give short shrift to Black girls—and I wasn’t disappointed. Despite giving a shout out in the acknowledgments section to women who are regularly rendered invisible in civil rights movements, no teenage Black girl has a voice or a significant role in the book. Black girls are the objects of desire for the book’s Black male characters—they’re there to “get all up on” and/or serve as props for teasing other boys. Considering the fact that young queer Black women FOUNDED the Black Lives Matter movement, it was disappointing to have a WHITE girl (written by the book’s white co-author, Brendan Kiely) be the one to introduce (at the end of the book). Black female victims of police brutality are named at the protest, but the one young Black woman with potential—Berry, a law student—is totally ignorant of her younger brother’s history with the police, and at the protest merely reads the script handed to her by her Black male boyfriend (and brother of the protagonist/victim). Imagine how different the book would be if instead of an older brother, Rashad had had an older sister—and she and her girlfriend organized the rally. Imagine if Tiffany, the girl Rashad hoped to “rub-a-dub on,” had been given a voice and an opportunity to talk about how police brutality impacted her life, her community, her personal sense of safety (think convicted rapist cop Daniel Holtzclaw and #BlackWomenMatter).

I don’t always get my Black male characters right. At the event in White Plains I talked with a Rastafarian scholar about how hard it was for me to make Judah homophobic. I want him to be a better person, but I can’t idealize a young man who realistically would disown his best friend for being gay. There’s been a lot of talk on social media about the appropriate way to “call out” or “call in” PoC who get it wrong when publishing books for young readers. I’m for accountability and I don’t have a lower standard for people of color—I actually hold them to a higher standard because unlike racist and/or ignorant whites, they should know better. We wouldn’t cut PoC officials slack if they played a role in poisoning the water in Flint, and we shouldn’t cut editors or authors slack when they produce toxic books for our kids. All American Boys is *not* toxic—it’s an important book, and I think it could be a useful teaching tool in the home and at school. It recently won a Coretta Scott King Honor Award and I believe its publication date was moved up in order to capitalize on the nation’s current interest in police brutality and youth movements. I have at least one professor friend who plans the teach the novel this spring, and I have already urged her to point out the absence of Black girls from the book. That kind of erasure isn’t new, and it’s the very reason we have hashtags like #SayHerName and #BlackWomenMatter.

I don’t always get my Black male characters right. At the event in White Plains I talked with a Rastafarian scholar about how hard it was for me to make Judah homophobic. I want him to be a better person, but I can’t idealize a young man who realistically would disown his best friend for being gay. There’s been a lot of talk on social media about the appropriate way to “call out” or “call in” PoC who get it wrong when publishing books for young readers. I’m for accountability and I don’t have a lower standard for people of color—I actually hold them to a higher standard because unlike racist and/or ignorant whites, they should know better. We wouldn’t cut PoC officials slack if they played a role in poisoning the water in Flint, and we shouldn’t cut editors or authors slack when they produce toxic books for our kids. All American Boys is *not* toxic—it’s an important book, and I think it could be a useful teaching tool in the home and at school. It recently won a Coretta Scott King Honor Award and I believe its publication date was moved up in order to capitalize on the nation’s current interest in police brutality and youth movements. I have at least one professor friend who plans the teach the novel this spring, and I have already urged her to point out the absence of Black girls from the book. That kind of erasure isn’t new, and it’s the very reason we have hashtags like #SayHerName and #BlackWomenMatter.

Toni Morrison advised us to write the books we want to read rather than waiting for others to write them for us. Which is just what I plan to do…