Zetta Elliott's Blog, page 38

April 4, 2016

roll out

There’s something happening in the universe. I do a lot of things for and by myself, and that’s usually how I guarantee that things will work out—because I’m on it! But I can’t publish a book all by myself, and my collaborators have faced challenges on their end that made getting this book out “on time” impossible. The first pub date for The Door at the Crossroads was 3/31 and then my cover designer had a health crisis, so I found another designer but then her internet connection was iffy, which made sharing files difficult…and so in the early hours of this morning I finally got the finished interior file for Crossroads. I hope to have the e-book out later today and the print book should be ready by the end of the week. Not a smooth roll out! And not how I like to operate. But maybe the universe is trying to teach me to let go and put my faith in others. What happens if the book isn’t ready on time? Nothing. Absolutely nothing! I’m aiming for Wednesday but if that doesn’t work out, it’ll be Friday instead. And that will still be okay…

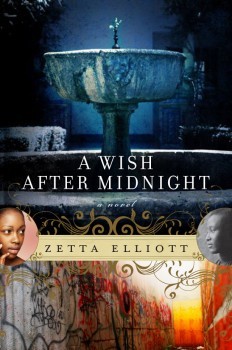

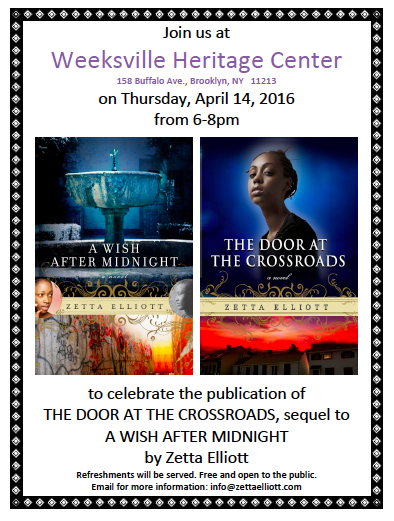

The Book Smugglers have been SO patient with all my randomness, and graciously offered to do the cover reveal on their site today—you can even enter a giveaway to win a copy of A Wish After Midnight and The Door at the Crossroads! And if you’re free on 4/14, you’re welcome to join us at the launch party. The book will be ready by then!

March 30, 2016

bending time

I’ve made plenty of mistakes in my life, but one area where I feel most like a failure is family. I have a large, loving extended family but no meaningful contact with my four siblings, and my mother and I mostly discuss the weather. So when I’m around other people’s families, I’m not always sure how to act. I’m lucky to have friends who welcome me into their homes and treat me like part of their clan. I spent last week in Massachusetts and for the first two days, I was my usual self in spaces that were familiar to me: a college classroom, a women’s center, and a charter school. Then I took the train out to western Mass and found my identity somewhat destabilized. On the one hand, I was in familiar territory; I taught at Mt. Holyoke College from 2006-2009, and had no trouble finding my way around campus. When I gave my talk before about a dozen students and faculty, I felt completely at ease and remembered how it felt to teach at a college full of intelligent and engaged women. Then I piled into the car with my friends and their kids, and we went to school for a music recital. And I didn’t really feel out of place, but I marveled at the lives my professor-friends lead—their endless energy, their determination to be present and engaged parents, the thought they put into choosing the best school for their Black children, their sustained advocacy on behalf of their kids…I was in awe. I’ve been thinking about my own fertility lately and the rational side of me KNOWS I am not ready to become a parent (especially a single parent). But spending a couple of days with my friends and their kids confirmed that fact and quieted the irrational, hormonal side of me that still wonders what it would be like. I finally finished my letter-writing project and speaking to my child self stirred up a lot of stuff for me—as I imagine parenting would. On the train to Cambridge I started reading Robin Bernstein’s brilliant book Racial Innocence and remembered how much I like being around intellectuals. My friends with kids are also intellectuals and we had some provocative conversations while I was there. And somehow they manage to pursue their scholarship while parenting full-time, so clearly it can be done. Will I ever give it a try? I don’t know. I wouldn’t want to fail at parenting. I wouldn’t want to become a mother and then realize my writing mattered more to me. There were plenty of times when I felt like a nuisance or a burden to my single mother, and I wouldn’t want to be responsible for making a child feel that way. So how do you avoid failure–by never trying? Or do you prepare as best you can and accept that you’ll always come up short? I’ve been stressed out for most of this month because The Door at the Crossroads was supposed to come out TOMORROW but a series of mishaps made that impossible. And things are still up in the air right now! Taking the train was more than a little uncomfortable because I had to endure sciatica and endometriosis pain at the same time—and there was NO quiet car! What if, in the midst of all this chaos, I also had to make sure my child’s needs were being met? I took 2 craft kits with me to MA and enjoyed sitting at a table with my (pretend) niece and nephew as we made paper cats and butterflies. The actual cat jumped on my shoulder twice and tried to burrow in my hair because that’s what she does to Renae. But I am not Renae, and I am not Robin. And after a couple of days, I came back to my life in Brooklyn and it felt SO good. Maybe it’s enough—for now—to write for and work with kids. Maybe once my novel comes out and I finish The Ghosts in the Castle and work my way through the other book projects in my queue…maybe then I’ll be ready to think about parenting. Maybe.

I’ve made plenty of mistakes in my life, but one area where I feel most like a failure is family. I have a large, loving extended family but no meaningful contact with my four siblings, and my mother and I mostly discuss the weather. So when I’m around other people’s families, I’m not always sure how to act. I’m lucky to have friends who welcome me into their homes and treat me like part of their clan. I spent last week in Massachusetts and for the first two days, I was my usual self in spaces that were familiar to me: a college classroom, a women’s center, and a charter school. Then I took the train out to western Mass and found my identity somewhat destabilized. On the one hand, I was in familiar territory; I taught at Mt. Holyoke College from 2006-2009, and had no trouble finding my way around campus. When I gave my talk before about a dozen students and faculty, I felt completely at ease and remembered how it felt to teach at a college full of intelligent and engaged women. Then I piled into the car with my friends and their kids, and we went to school for a music recital. And I didn’t really feel out of place, but I marveled at the lives my professor-friends lead—their endless energy, their determination to be present and engaged parents, the thought they put into choosing the best school for their Black children, their sustained advocacy on behalf of their kids…I was in awe. I’ve been thinking about my own fertility lately and the rational side of me KNOWS I am not ready to become a parent (especially a single parent). But spending a couple of days with my friends and their kids confirmed that fact and quieted the irrational, hormonal side of me that still wonders what it would be like. I finally finished my letter-writing project and speaking to my child self stirred up a lot of stuff for me—as I imagine parenting would. On the train to Cambridge I started reading Robin Bernstein’s brilliant book Racial Innocence and remembered how much I like being around intellectuals. My friends with kids are also intellectuals and we had some provocative conversations while I was there. And somehow they manage to pursue their scholarship while parenting full-time, so clearly it can be done. Will I ever give it a try? I don’t know. I wouldn’t want to fail at parenting. I wouldn’t want to become a mother and then realize my writing mattered more to me. There were plenty of times when I felt like a nuisance or a burden to my single mother, and I wouldn’t want to be responsible for making a child feel that way. So how do you avoid failure–by never trying? Or do you prepare as best you can and accept that you’ll always come up short? I’ve been stressed out for most of this month because The Door at the Crossroads was supposed to come out TOMORROW but a series of mishaps made that impossible. And things are still up in the air right now! Taking the train was more than a little uncomfortable because I had to endure sciatica and endometriosis pain at the same time—and there was NO quiet car! What if, in the midst of all this chaos, I also had to make sure my child’s needs were being met? I took 2 craft kits with me to MA and enjoyed sitting at a table with my (pretend) niece and nephew as we made paper cats and butterflies. The actual cat jumped on my shoulder twice and tried to burrow in my hair because that’s what she does to Renae. But I am not Renae, and I am not Robin. And after a couple of days, I came back to my life in Brooklyn and it felt SO good. Maybe it’s enough—for now—to write for and work with kids. Maybe once my novel comes out and I finish The Ghosts in the Castle and work my way through the other book projects in my queue…maybe then I’ll be ready to think about parenting. Maybe.

March 13, 2016

“Reflecting Our Communities”

On Friday I got a confusing email from someone who’d read an article about me in Brooklyn Family magazine. I’d done the interview back in January and didn’t realize it had come out, but passed a kiosk moments after reading the email and found myself on a two-page spread! So I ended the week on a high note but this weekend has not been very productive. Right now I’m supposed to be writing a letter to my younger self, but it’s HARD and I keep putting it off even though it was due last week. PBS is on a pledge drive so there’s nothing to watch, and I’m caught up on the latest episode of Vikings. I spend so much time thinking about my childhood…I don’t know why this letter leaves me stumped. My friend also suggested we try writing to our adult selves from a child’s perspective, but that feels even harder. Somehow I feel like my child-self would be disappointed with the woman I’ve become. I think I had a very different vision of myself when I was young, and definitely thought I’d have a family and be a loving parent by now. Instead I’ve birthed books—The Door at the Crossroads will bring the total to 23 (for young readers, at least). I spent a fair amount of time alone as a child but I’m not sure I ever imagined living so far away from my family as an adult. My sister once said, “You were such a happy kid—what happened?” I don’t think I’m a miserable spinster (yet) but my parents’ divorce definitely changed me, and then my prolonged “awkward phase,” followed by a bout of depression my senior year in high school. What do you say to someone who’s still evolving? “Be patient with yourself and be kind.” My friend had a dream where her child-self said, “You have time.” Which is sage advice! Everything isn’t as urgent as we’d like to believe. I’m a lot like my child-self still…I love to collect shiny, sparkly things, and I love being around trees and exploring wild spaces. Simple things amuse me and I’m glad that hasn’t changed. I guess I’ll try to spin that into some sort of narrative before this day ends.

On Friday I got a confusing email from someone who’d read an article about me in Brooklyn Family magazine. I’d done the interview back in January and didn’t realize it had come out, but passed a kiosk moments after reading the email and found myself on a two-page spread! So I ended the week on a high note but this weekend has not been very productive. Right now I’m supposed to be writing a letter to my younger self, but it’s HARD and I keep putting it off even though it was due last week. PBS is on a pledge drive so there’s nothing to watch, and I’m caught up on the latest episode of Vikings. I spend so much time thinking about my childhood…I don’t know why this letter leaves me stumped. My friend also suggested we try writing to our adult selves from a child’s perspective, but that feels even harder. Somehow I feel like my child-self would be disappointed with the woman I’ve become. I think I had a very different vision of myself when I was young, and definitely thought I’d have a family and be a loving parent by now. Instead I’ve birthed books—The Door at the Crossroads will bring the total to 23 (for young readers, at least). I spent a fair amount of time alone as a child but I’m not sure I ever imagined living so far away from my family as an adult. My sister once said, “You were such a happy kid—what happened?” I don’t think I’m a miserable spinster (yet) but my parents’ divorce definitely changed me, and then my prolonged “awkward phase,” followed by a bout of depression my senior year in high school. What do you say to someone who’s still evolving? “Be patient with yourself and be kind.” My friend had a dream where her child-self said, “You have time.” Which is sage advice! Everything isn’t as urgent as we’d like to believe. I’m a lot like my child-self still…I love to collect shiny, sparkly things, and I love being around trees and exploring wild spaces. Simple things amuse me and I’m glad that hasn’t changed. I guess I’ll try to spin that into some sort of narrative before this day ends.

March 11, 2016

thank you, Bank Street

In 2015 I found out that Room in My Heart was included in the annual list of Best Children’s Books compiled by the Bank Street Center for Children’s Literature. This year I’m proud to have TWO of my self-published titles included in their 2016 list—I Love Snow and A Wave Came Through Our Window, which received a star for outstanding merit! I noticed that once Room in My Heart made the Bank Street list, both the NYPL and the BPL added the book to their collection. And when I checked their catalogs yesterday, I saw that three more of my self-published books were “on order.” So things are slowly starting to change! By the end of this month, I will have self-published 19 books and about 5 of those titles will be available at the

In 2015 I found out that Room in My Heart was included in the annual list of Best Children’s Books compiled by the Bank Street Center for Children’s Literature. This year I’m proud to have TWO of my self-published titles included in their 2016 list—I Love Snow and A Wave Came Through Our Window, which received a star for outstanding merit! I noticed that once Room in My Heart made the Bank Street list, both the NYPL and the BPL added the book to their collection. And when I checked their catalogs yesterday, I saw that three more of my self-published books were “on order.” So things are slowly starting to change! By the end of this month, I will have self-published 19 books and about 5 of those titles will be available at the ![Pageflex Persona [document: PRS0000038_00049]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1428034279i/14353412.jpg) library. I plan to keep pushing for inclusion and hope you will, too. And I’d like to thank the Children’s Book Committee at Bank Street for having open minds and giving my books their stamp of approval. No author should have to win an award or make a “best of” list just to have their book available in public libraries, but indie authors are generally held to a higher standard…which isn’t fair, but we persist!

library. I plan to keep pushing for inclusion and hope you will, too. And I’d like to thank the Children’s Book Committee at Bank Street for having open minds and giving my books their stamp of approval. No author should have to win an award or make a “best of” list just to have their book available in public libraries, but indie authors are generally held to a higher standard…which isn’t fair, but we persist!

March 10, 2016

come to Cambridge!

If you’re in the Boston area, I hope you’ll come out to the Women’s Center at Harvard to hear my public talk on March 22. I’m honored that Prof. Robin Bernstein is teaching A Wish After Midnight in her course, “The Child in African America,” and I look forward to meeting her students while I’m on campus. Robin also arranged this evening talk, and I know there are lots of kid lit people in Boston so I hope to see you there!

If you’re in the Boston area, I hope you’ll come out to the Women’s Center at Harvard to hear my public talk on March 22. I’m honored that Prof. Robin Bernstein is teaching A Wish After Midnight in her course, “The Child in African America,” and I look forward to meeting her students while I’m on campus. Robin also arranged this evening talk, and I know there are lots of kid lit people in Boston so I hope to see you there!

March 9, 2016

MUST.STOP.WRITING.

A novel’s never done. Not for the writer. I finished The Door at the Crossroads in January but I’m tinkering with it still, adding a sentence here and there, inserting a paragraph to extend or clarify a conversation. But it has to stop. At some point every author has to walk away from her book and let it live on its own. I’m like an annoying helicopter parent who won’t let her teenager walk out into the world for fear others will point out her flaws and prey on her weaknesses. I find myself anticipating critiques, and so I go back to the novel and try to answer questions that actually haven’t yet been asked. But it has to stop. Still waiting on the latest updates to the cover but have set a date for the launch party—I hope you can join us on April 14 from 6-8pm at the Weeksville Heritage Center! I’m not good at parties but this book has been a long time coming, so I think it’s important to stop and celebrate.

A novel’s never done. Not for the writer. I finished The Door at the Crossroads in January but I’m tinkering with it still, adding a sentence here and there, inserting a paragraph to extend or clarify a conversation. But it has to stop. At some point every author has to walk away from her book and let it live on its own. I’m like an annoying helicopter parent who won’t let her teenager walk out into the world for fear others will point out her flaws and prey on her weaknesses. I find myself anticipating critiques, and so I go back to the novel and try to answer questions that actually haven’t yet been asked. But it has to stop. Still waiting on the latest updates to the cover but have set a date for the launch party—I hope you can join us on April 14 from 6-8pm at the Weeksville Heritage Center! I’m not good at parties but this book has been a long time coming, so I think it’s important to stop and celebrate.

If you’re in the NYC area, you definitely want to check out the Kweli Writers Conference. I’ll be on two panels but check out all the others—this is your chance to meet and learn from writers, illustrators, editors, and agents:

The Color of Children’s Literature

Program Schedule

Saturday, April 9, 2016

7:30am – 8:45am

Registration and Coffee

8:45am – 9:00am (Volvo Hall)

Welcome and Introduction

9:00am – 9:55am (Volvo Hall)

Keynote by Edwidge Danticat

10:00am – 10:55am (Volvo Hall)

Publishing 101

Panel Discussion moderated by Lynne Polvino (Clarion), featuring:

Regina Brooks, Antonio Gonzalez, Stacy Whitman, Phoebe Yeh

11:00am – 12:00pm (Volvo Hall)

Industry Overview

Panel Discussion moderated by Connie Hsu (Macmillan), featuring:

Victoria Wells Arms, Stacey Barney, Zetta Elliott, Cheryl Hudson

12:00pm – 1:30pm

Lunch Break

1:30pm – 2:25pm

A. Working Through the Editorial Process (Volvo Hall)

Panel Discussion moderated by Natalia Remis (Scholastic), featuring:

Tracey Baptiste, Cheryl Klein, Olugbemisola Rhuday-Perkovich, Eileen Robinson

B. Picture Books Roundtable (Conference Room)

Joanna Cardenas, Zetta Elliott, Cheryl Hudson, Sean Qualls and Eric Velasquez

2:30pm – 3:25pm

A. Building a Platform (Volvo Hall)

Panel Discussion moderated by Olugbemisola Rhuday-Perkovich, featuring:

Dhonielle Clayton, Antonio Gonzalez, Andrew Harwell, Daniel José Older, Stacy Whitman

B. Writing Middle Grade and Young Adult (Conference Room)

TS Ferguson, Grace Kendall, Alvina Ling, Eileen Robinson

3:30pm – 5:30pm (Volvo Hall)

Manuscript Critiques

3:30pm – 4:25pm

Submissions Panel (Conference Room)

Panel Discussion moderated by Jessica Echeverria (Lee & Low Books), featuring:

Celeste Lim, Beth Phelan, Rachel Stark, Harold Underdown

4:30pm – 5:30pm

Success Stories (Conference Room)

Panel Discussion moderated by Katherine R. Harrison (Knopf Books), featuring:

Joseph Bruchac, Sheela Chari, Nnedi Okorafor, Daniel José Older

6pm – 7:30pm (Volvo Hall)

Wine and Cheese Reception

March 2, 2016

did you know…?

Did you know that many public libraries won’t acquire a book unless it has been reviewed in a professional journal like Booklist or Publishers Weekly? And did you know that almost all of those review outlets refuse to review self-published books? (Kirkus will if you’ve got $400) So if you’re a writer of color and you’ve been shut out of the publishing industry, deciding to self-publish means facing yet another set of obstacles. UNLESS a radical librarian from Oakland decides she will take on the task of reviewing self-published books in a quarterly column for School Library Journal! Here’s the introduction to Amy Martin’s SLJ column “Indie Voices,” which provides the rationale for adding indie titles to library collections:

Did you know that many public libraries won’t acquire a book unless it has been reviewed in a professional journal like Booklist or Publishers Weekly? And did you know that almost all of those review outlets refuse to review self-published books? (Kirkus will if you’ve got $400) So if you’re a writer of color and you’ve been shut out of the publishing industry, deciding to self-publish means facing yet another set of obstacles. UNLESS a radical librarian from Oakland decides she will take on the task of reviewing self-published books in a quarterly column for School Library Journal! Here’s the introduction to Amy Martin’s SLJ column “Indie Voices,” which provides the rationale for adding indie titles to library collections:

Self-publishing platforms like CreateSpace and cheap, accessible printing technology have made it easier than ever for authors to publish independently. This, coupled with the misguided notion that writing books for children is “easy,” can lead to some paltry offerings. After all, what book couldn’t benefit from a talented editorial, design, and marketing team? Yet despite its checkered reputation, a growing number of talented authors and illustrators are producing finely written, beautifully illustrated, and smartly designed works that completely skirt the traditional publishing avenues.

It’s difficult to break into the business of making children’s books. That goes double for people of color, queer authors, the differently abled, and/or those creating stories about people who identify with one or more of those categories. Self-publishing can give voice to marginalized people who may be overlooked by mainstream publishing. In this first column, I recommend a handful of self-published titles whose skillful presentations of diverse stories make them worthy purchase for libraries serving children.

I’m honored to have I Love Snow included in Amy’s list of seven great indie titles. I should note that Amy Cheney also reviews for SLJ and already welcomes indie authors; she even set up an award for books that reflect the realities of urban youth. IndieReader also shines a light on self-published books by marginalized writers. They included The Last Bunny in Brooklyn in their list of “6 Titles to Help #DiversifyYourReads.” Joe Sutton’s remarks echo those made by Amy:

I’m honored to have I Love Snow included in Amy’s list of seven great indie titles. I should note that Amy Cheney also reviews for SLJ and already welcomes indie authors; she even set up an award for books that reflect the realities of urban youth. IndieReader also shines a light on self-published books by marginalized writers. They included The Last Bunny in Brooklyn in their list of “6 Titles to Help #DiversifyYourReads.” Joe Sutton’s remarks echo those made by Amy:

One of the best things about self-publishing is how it empowers diverse authors, who might otherwise need to get “permission” from more short-sighted traditional publishers, to get their works published and read. And with many less expensive options (ebooks, POD) replacing high-price vanity presses, another barrier has been lifted, making self-publishing a more accessible and less costly option.

While the traditional publishing industry still devotes most of its attention to white, male authors, the indie scene has an abundance of diversity and cultures. If you’re resolving to add a little diversity to your library, start with this handful of authors!

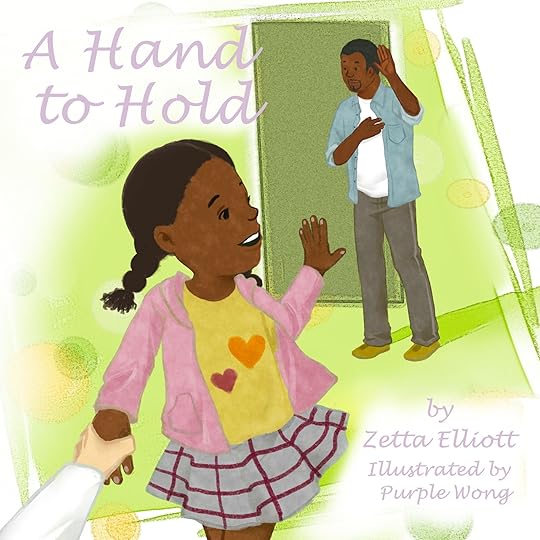

I sent out digital review copies of A Hand to Hold yesterday and the response was heartwarming! I feel so blessed to have the support of teachers, and librarians, and other book lovers. Their excitement about my stories means young readers around the country—and the world—will soon have more “mirror books” in their hands! If you’re a librarian, I hope you’ll consider whether the policies at your branch are contributing to the “diversity gap.” Please don’t place yet another barrier in the path of marginalized writers…

I sent out digital review copies of A Hand to Hold yesterday and the response was heartwarming! I feel so blessed to have the support of teachers, and librarians, and other book lovers. Their excitement about my stories means young readers around the country—and the world—will soon have more “mirror books” in their hands! If you’re a librarian, I hope you’ll consider whether the policies at your branch are contributing to the “diversity gap.” Please don’t place yet another barrier in the path of marginalized writers…

February 29, 2016

Writing While Black/Writing While Indigenous: Two voices speak on excellence

Ambelin: How to begin to speak about excellence? I’m worried that in speaking I’ll contribute to the phenomenon whereby Indigenous writers and writers of colour are held to impossibly high standards, while white writers are often held to no standard at all when it comes to the representation of others. I’m aware that I have no right to tell other Indigenous writers or writers of colour what should constitute excellence for them; we are diverse peoples with diverse cultures, experiences and histories, and all these things influence our individual views on excellence. But I still think there is a place for all diverse writers to personally reflect on what excellence means to each of us, and I believe it’s an important conversation to have. Zetta, you wrote in your first post that you were “tired because the fight seems never-ending, and progress minimal.” I feel the same. On the worst of days, I do what the generations who came before me did – I take the long view, gazing beyond the span of my existence into the undetermined future. And I think about how powerfully it matters to have the voices of so many diverse peoples speaking to these issues in cyberspace. We are creating a record, and if we don’t succeed in changing anything for ourselves, we will at least place our knowledge and insights into the hands of the writers who come after us.

Ambelin: How to begin to speak about excellence? I’m worried that in speaking I’ll contribute to the phenomenon whereby Indigenous writers and writers of colour are held to impossibly high standards, while white writers are often held to no standard at all when it comes to the representation of others. I’m aware that I have no right to tell other Indigenous writers or writers of colour what should constitute excellence for them; we are diverse peoples with diverse cultures, experiences and histories, and all these things influence our individual views on excellence. But I still think there is a place for all diverse writers to personally reflect on what excellence means to each of us, and I believe it’s an important conversation to have. Zetta, you wrote in your first post that you were “tired because the fight seems never-ending, and progress minimal.” I feel the same. On the worst of days, I do what the generations who came before me did – I take the long view, gazing beyond the span of my existence into the undetermined future. And I think about how powerfully it matters to have the voices of so many diverse peoples speaking to these issues in cyberspace. We are creating a record, and if we don’t succeed in changing anything for ourselves, we will at least place our knowledge and insights into the hands of the writers who come after us.

Zetta: Agreed! And I feel the same way about my books. A white woman once remarked that self-published books rarely sell over 100 copies and I thought to myself, “So?” In her mind, that makes the act of self-publishing futile but to me, reaching 100 kids and potentially transforming their lives is not a waste of time. I really want to explore the connection between quantity and quality in the kid lit community. No doubt most writers aspire to see their book on the New York Times Bestseller list, but does that in any way indicate excellence? If 3000 novels for young readers are published annually in the US and only 30 are by Black authors, what does that do to the potential for excellence? Black-authored books in the US are eligible for the Coretta Scott King Award, a prize reserved for African Americans authors and illustrators. But the same people win the award over and over again. Kyra Hicks finds that from 1970-2012,

…authors or illustrators who have received two or more CSK awards or honors account for the majority of all award recipients. For example, 26 African-American authors (33 percent) have been honored with 67 percent of all the author awards given since 1970. And, 17 Black illustrators (40 percent) have 75 percent of all the illustrator awards given.

In 2015 there were only 2 debut Black authors with middle grade or young adult novels. Can we achieve excellence without competition? Are award committees really rewarding excellence when the majority of Black writers can’t even get a foot in the door? In the 19th century, slave narratives had to be authenticated by Whites in order to be deemed legitimate, and formerly enslaved women and men had to self-censor at times in order to avoid offending the “delicate sensibilities” of their genteel White audience. One could argue that this authentication process continues to this day since the publishing industry is dominated by White women.

Perhaps our academic background makes us accustomed and/or indifferent to the limited circulation of significant texts. Perhaps our cultures have taught us that writing is not just for the self but for the community—and every member of the community counts. With this important dialogue we are creating an archive, inserting ourselves into history because these conversations do leave a digital footprint that may guide someone somewhere who feels lost and alone.

Ambelin: And that footprint is so necessary – because diverse writers cannot rely on the people whom writers are supposed to be able to rely upon. Most agents, editors, and reviewers don’t know enough about us to be able to give us meaningful feedback on the ways in which we are representing our worlds – in fact, their advice may well be wrong. I know that I am far from the only Indigenous author to have been told that I am not writing to the ‘Indigenous experience’ (as if there is only one experience shared amongst the vast diversity of the Indigenous peoples of the earth, and as if that experience has been accurately captured by the works produced about us by white people, which is generally the frame of reference against which my writing is being judged). So I must seek other processes to help me achieve excellence. As part of this, I read all I can find written by Indigenous and other diverse peoples on writing and representation. Everything I write is reviewed by other Indigenous people before it is published. If I am in doubt as to whether something should be said, I do not speak. And I am as sensitive as I can be to the contexts in which things will be read, to the many ways in which my words can misread and misinterpreted.

Ambelin: And that footprint is so necessary – because diverse writers cannot rely on the people whom writers are supposed to be able to rely upon. Most agents, editors, and reviewers don’t know enough about us to be able to give us meaningful feedback on the ways in which we are representing our worlds – in fact, their advice may well be wrong. I know that I am far from the only Indigenous author to have been told that I am not writing to the ‘Indigenous experience’ (as if there is only one experience shared amongst the vast diversity of the Indigenous peoples of the earth, and as if that experience has been accurately captured by the works produced about us by white people, which is generally the frame of reference against which my writing is being judged). So I must seek other processes to help me achieve excellence. As part of this, I read all I can find written by Indigenous and other diverse peoples on writing and representation. Everything I write is reviewed by other Indigenous people before it is published. If I am in doubt as to whether something should be said, I do not speak. And I am as sensitive as I can be to the contexts in which things will be read, to the many ways in which my words can misread and misinterpreted.

Zetta: I just wrote about this last month when I took issue with a Black-authored book that completely erased young Black women from the Black Lives Matter movement—even though it was founded by young queer Black women. That YA novel went on to win numerous awards and the Black male author ultimately took responsibility for “missing the mark,” which only further impressed his many (white female) fans. People on social media remarked about our exemplary exchange—“so civil!”—but said very little about what it means that this book got published to great acclaim without anyone else noticing (or caring) that it potentially harms young Black women. In a follow-up post I wrote,

Zetta: I just wrote about this last month when I took issue with a Black-authored book that completely erased young Black women from the Black Lives Matter movement—even though it was founded by young queer Black women. That YA novel went on to win numerous awards and the Black male author ultimately took responsibility for “missing the mark,” which only further impressed his many (white female) fans. People on social media remarked about our exemplary exchange—“so civil!”—but said very little about what it means that this book got published to great acclaim without anyone else noticing (or caring) that it potentially harms young Black women. In a follow-up post I wrote,

…whenever a problematic book comes out, it points to a failure of process. Writing is a solitary activity, but publishing a book is not. It would have been great if the editor of this novel thought about the exclusion of Black girls. It would have meant a lot to me if some reviewers gave the book the praise it deserves but also pointed out this particular limitation. The fact that neither of those things happened confirms for me that a lot of people in the kid lit community aren’t really thinking about Black girls. I don’t generally review books but I published my critique on my blog because I was trying to be strategic. I’ve only met Jason once, but he seemed like an open-minded person and the comment he left on my blog proves that to be true. I also heard he has a ten-book deal, which means he’ll have plenty of opportunities to write (better) Black female characters in the future. Will reviewers and librarians and editors educate themselves about intersectionality and misogynoir? I doubt it. And that puts the onus on the writer—WE have to work harder because we can’t rely on others in the publishing process to get it right. No writer is perfect—I make mistakes all the time. But I care about Black youth and I know Jason does, too. And that’s why we have to help and look out for one another.

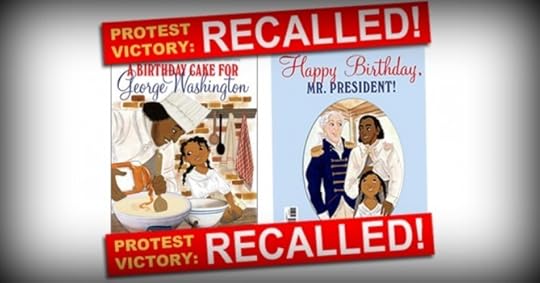

Yet as Scholastic’s controversial publication and recall of A Birthday Cake for George Washington makes clear, having a Black editor doesn’t guarantee that a book about an aspect of the Black experience will be properly vetted. Editors don’t always recognize that different cultural groups have particular storytelling conventions, but cultural competence isn’t the only issue. As you pointed out in your first post, storytelling plays a crucial role in the ongoing struggle for liberation but I suspect most people involved in the kid lit community don’t see the publication and promotion of children’s literature as a political act. Many would agree that books can empower young readers, but few seem to recognize that inaccurate and/or insensitive books can be toxic.

Ambelin: I think, too, that its important to many of us to honour the lives (and the struggles) of all marginalised peoples, not only the groups we belong to. But intersectionality is not an easy thing to address within the limits of a narrative – so do we find ways to convey where different experiences connect and diverge? Where are the spaces for diverse writers to have these conversations amongst ourselves in the first place? And how do we remain true to who we are whilst continually negotiating literary spaces that are not our own and reflect nothing of our identities? I don’t think any of these questions have easy answers. One of my picture books has been criticised as being didactic. The criticism is correct in that it is didactic. But in non-Western cultures, including Indigenous cultures, didacticism is not necessarily a negative; and amongst the Aboriginal peoples of Australia, stories often ‘circle back’ to the message of the tale. I am not suggesting that Indigenous cultures are incapable of change such that we must always tell stories within specific fixed and unvarying forms; a view of Indigenous cultures as frozen relics is a myth generated by anthropological texts and other colonial works of epic fantasy. Nor am I suggesting that I, or any Indigenous writer, is a passive victim of Western literary forms; I am as capable of resistance and subversion as my ancestors were in their long battle against colonialism. But for this particular story, I concluded that it needed to be told in this particular way. It drew adverse comment for didacticism from white reviewers. It is also the book which Indigenous people – and other peoples from non-Western backgrounds – regularly tell me is their favourite of my works. My conclusion is this: in order to be true to myself as an Indigenous writer, there will be times when I must contravene Western literary ideals of what it means to be excellent.

Ambelin: I think, too, that its important to many of us to honour the lives (and the struggles) of all marginalised peoples, not only the groups we belong to. But intersectionality is not an easy thing to address within the limits of a narrative – so do we find ways to convey where different experiences connect and diverge? Where are the spaces for diverse writers to have these conversations amongst ourselves in the first place? And how do we remain true to who we are whilst continually negotiating literary spaces that are not our own and reflect nothing of our identities? I don’t think any of these questions have easy answers. One of my picture books has been criticised as being didactic. The criticism is correct in that it is didactic. But in non-Western cultures, including Indigenous cultures, didacticism is not necessarily a negative; and amongst the Aboriginal peoples of Australia, stories often ‘circle back’ to the message of the tale. I am not suggesting that Indigenous cultures are incapable of change such that we must always tell stories within specific fixed and unvarying forms; a view of Indigenous cultures as frozen relics is a myth generated by anthropological texts and other colonial works of epic fantasy. Nor am I suggesting that I, or any Indigenous writer, is a passive victim of Western literary forms; I am as capable of resistance and subversion as my ancestors were in their long battle against colonialism. But for this particular story, I concluded that it needed to be told in this particular way. It drew adverse comment for didacticism from white reviewers. It is also the book which Indigenous people – and other peoples from non-Western backgrounds – regularly tell me is their favourite of my works. My conclusion is this: in order to be true to myself as an Indigenous writer, there will be times when I must contravene Western literary ideals of what it means to be excellent.

Zetta: The novel I’m about to publish (The Door at the Crossroads, sequel to A Wish After Midnight) was also called “didactic” years ago by one of the very few woman of color editors in Canadian children’s publishing. In this case, I think she was reacting to the explicit political content of the book, which I was unwilling to remove or water down. I think most editors—regardless of race—envision the audience for kid lit to be White middle-class kids and teens. And they no doubt realize that the overwhelming majority of educators and librarians purchasing books for schools are also White and middle-class. But since White middle-class readers are definitely NOT my target audience, I resent being asked to alter my story to keep them comfortable. Right now I have a few beta readers looking at Crossroads; one White woman reader said she found the novel hard to read and yet couldn’t put it down, and a Black woman reader said the characters’ harrowing escape from slavery in the book was making it hard for her to be around Whites in real life. That tells me my book is doing exactly what I want it to do. Literature that appeases its readers just upholds the status quo and I want my books to disrupt, disrupt, disrupt! I think Black excellence has a lot to do with risk, and the publishing industry is notoriously risk-averse even as it is also self-congratulatory (same with Hollywood, and the lily-white Oscars are on as I write this). A young Black woman author just got a six-figure advance for a YA novel about the Black Lives Matter movement. Will there be queer Black women in this book? I hope so, but I’m not holding my breath. And even if it does have radical content, one book—and one book deal that enriches one author—is NOT a sign of progress. It costs the industry nothing to make a gesture like that because nothing about the structure of the industry—and the balance of power—has to change.

Zetta: The novel I’m about to publish (The Door at the Crossroads, sequel to A Wish After Midnight) was also called “didactic” years ago by one of the very few woman of color editors in Canadian children’s publishing. In this case, I think she was reacting to the explicit political content of the book, which I was unwilling to remove or water down. I think most editors—regardless of race—envision the audience for kid lit to be White middle-class kids and teens. And they no doubt realize that the overwhelming majority of educators and librarians purchasing books for schools are also White and middle-class. But since White middle-class readers are definitely NOT my target audience, I resent being asked to alter my story to keep them comfortable. Right now I have a few beta readers looking at Crossroads; one White woman reader said she found the novel hard to read and yet couldn’t put it down, and a Black woman reader said the characters’ harrowing escape from slavery in the book was making it hard for her to be around Whites in real life. That tells me my book is doing exactly what I want it to do. Literature that appeases its readers just upholds the status quo and I want my books to disrupt, disrupt, disrupt! I think Black excellence has a lot to do with risk, and the publishing industry is notoriously risk-averse even as it is also self-congratulatory (same with Hollywood, and the lily-white Oscars are on as I write this). A young Black woman author just got a six-figure advance for a YA novel about the Black Lives Matter movement. Will there be queer Black women in this book? I hope so, but I’m not holding my breath. And even if it does have radical content, one book—and one book deal that enriches one author—is NOT a sign of progress. It costs the industry nothing to make a gesture like that because nothing about the structure of the industry—and the balance of power—has to change.

Ambelin: I am always so happy to hear of the successes of other diverse writers – I know how heavily the odds are stacked against all of us. But as you rightly point out, the success of some isn’t evidence of those odds changing. A world of literature that reflected the make up of the actual world (in regard to both who gets published, and who is working in the industry) would be evidence of change, and we’re a long way from that. The individual voices of the marginalised should be difficult for people to make out not because the structures of privilege prevent us from speaking, but because there are so many of us speaking that we overwhelm with our multitude, with our wealth of stories that shout out the many truths of our existence. Instead, there are so few of our voices to speak to the struggles and triumphs of so many. I feel the weight of that, heavy upon my shoulders. In a YA context I write Indigenous futurisms, a form of storytelling whereby Indigenous peoples use the speculative fiction genre to challenge colonialism and to envision Indigenous futures. In drawing on colonial history, I believe I have a dual responsibility. The first aspect of this responsibility is to speak to the truth of Indigenous resistance and agency, and in so doing, deny the lie that we were unresisting victims who faded away in the face of the so-called ‘superiority’ of Western cultures. The second aspect is to convey the way in which colonialism wounded – and ended – the lives of so many. The triumphs of oppressed peoples is a tribute to the spirit of the oppressed. It does not – ever – make the oppression any less evil that it was. And I think there is a danger that narratives which speak to our triumphs can be interpreted by those whose ancestors did not experience these histories (or the present-day disadvantage, discrimination and multigenerational trauma that resulted) as indicating that things were ‘not that bad’. So I believe excellence in this context means celebrating the incredible spirit of Indigenous peoples, but doing so in a way that always names colonialism and other forms of oppression for the evils that they were (and are).

Zetta: I couldn’t agree more. Speculative fiction operates differently without our cultures, and I worry that decades of Harry Potter mania will make is harder for kids of color to imagine themselves operating within magical worlds. In my 2014 essay “The Trouble With Magic,” I build upon Ramón Saldívar’s concept of “historical fantasy,”

…which “links desire and imagination, utopia and history, but with a more pronounced edge intended to redeem, or perhaps even create, a new moral and social order” (587). Saldívar contends that, “in the twenty-first century, the relationship between race and social justice, race and identity, and indeed, race and history requires [writers of colour] to invent a new ‘imaginary’ for thinking about the nature of a just society and the role of race in its construction. It also requires the invention of new forms to represent it” (574). Though Saldívar makes no mention of children’s literature in his discussion, I believe his assessment of contemporary American fiction should be extended to include the needs of young readers, who are more diverse than ever before yet rarely find books that confront the nation’s problematic, ongoing history of social injustice. By linking contemporary racial inequality to the history of enslavement and racial terror in New York City, my novels depart from the work of Ruth Chew by attempting to “reverse the usual course of fantasy, turning it away from latent forms of daydream, delusion, and denial, toward the manifold surface features of history” (Saldívar 595).

That essay can be found in any library database that includes Jeunesse: young people, texts, culture (you can also email me for a PDF). We can—and sometimes must—theorize about our work, but in the end I’m hoping our stories will help young people to theorize their own experience. Magical stories are always about power, and our youth need to know how to wield power and how power has been/is being used by others to oppress our communities.

February 26, 2016

stories heal

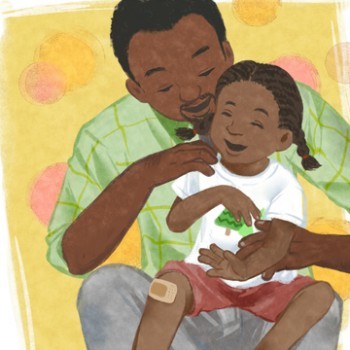

My first newsletter of 2016 is ready to go out (read it here), and I’ve got two new picture books to share with readers. I had the illustrations from A Hand to Hold with me in London and shared them with a friend—she got a bit weepy and said her husband probably couldn’t read the book with their daughter because he’d start crying, too! It’s hard to let go of your child and stand back while s/he engages with the world alone. I used to love holding my father’s hand but my dad moved out after the divorce and so I learned at age 8 what it meant to rely on myself. When I moved to NYC at age 21, I was amused when my father would reach for my hand before we crossed the street. In his mind, I was still a little girl and he didn’t believe I could navigate the city on my own. Now that he’s gone, I often wish I could see his “blinking” hand—he never said, “Take my hand.” He’d just “blink” his hand, open/closed, open/closed, until I slipped my hand inside. My father wasn’t really there for me the way the father in the book is there for his daughter, but I consider A Hand to Hold a tribute to my dad just the same…

My first newsletter of 2016 is ready to go out (read it here), and I’ve got two new picture books to share with readers. I had the illustrations from A Hand to Hold with me in London and shared them with a friend—she got a bit weepy and said her husband probably couldn’t read the book with their daughter because he’d start crying, too! It’s hard to let go of your child and stand back while s/he engages with the world alone. I used to love holding my father’s hand but my dad moved out after the divorce and so I learned at age 8 what it meant to rely on myself. When I moved to NYC at age 21, I was amused when my father would reach for my hand before we crossed the street. In his mind, I was still a little girl and he didn’t believe I could navigate the city on my own. Now that he’s gone, I often wish I could see his “blinking” hand—he never said, “Take my hand.” He’d just “blink” his hand, open/closed, open/closed, until I slipped my hand inside. My father wasn’t really there for me the way the father in the book is there for his daughter, but I consider A Hand to Hold a tribute to my dad just the same…

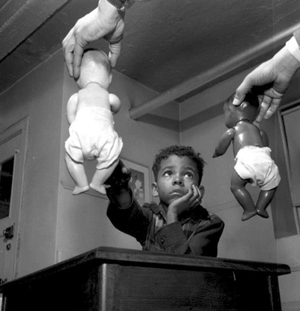

Troy Johnson at AALBC gave me the opportunity to write a guest post for his blog: “Who Will Write a Story for the Children of Eric Garner?” In my essay I ask whether “white books” are as toxic to Black children as white dolls:

Troy Johnson at AALBC gave me the opportunity to write a guest post for his blog: “Who Will Write a Story for the Children of Eric Garner?” In my essay I ask whether “white books” are as toxic to Black children as white dolls:

Think of the doll test developed by psychologists Mamie and Kenneth Clark in the 1940s. Eventually used in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case, the Drs. Clark intended the experiment to prove “the influence of race and color and status on the self-esteem of children.” In 2005, teen filmmaker Kiri Davis recreated the doll test in her short film A Girl Like Me. It’s heartbreaking to watch Black children reaching without hesitation for the white doll when asked, “Which is the nice doll?” and then faltering when asked to point out the doll that looks like them (“the bad doll”). What would happen if we conducted a similar test with books instead of dolls—would the results be the same?

Several YA authors have been discussing this on Facebook so we may take it to Twitter—stay tuned!

February 24, 2016

decolonize kid lit

The CCBC has posted its findings for 2015, and they are as disappointing as ever. They separate the books into categories—by, about, and by but not about. Keep in mind they review over 3000 books each year:

261 books had significant African or African American content

86 of these were by Black authors and/or illustrators

100 books were by Black book creators

14 of these had no visible African/African-American cultural content

41 books had American Indian / First Nations themes, topics, or characters

17 of these were by American Indian/First Nations book creators

18 books were by American Indian / First Nations authors and/or illustrators

1 of these had no visible American Indian/First Nations content

111 books had significant Asian/Pacific or Asian/Pacific American content

43 of these were by Asian/Pacific or Asian/Pacific American

173 books were by authors and/or illustrators of Asian/Pacific heritage

130 of these had no visible Asian/Pacific or Asian/Pacific American content

82 books had significant Latino content

40 of these were by Latino/a authors and/or illustrators

57 books were by Latino/a authors and/or illustrators

17 of these had no visible Latino content

So if there were 261 books published ABOUT Black folks but only 86 of those books were BY Black folks, then that means white folks wrote 161 books about Black people. Are you ok with that? I’m not. And once again we see Asian Pacific American authors writing mostly about white people—they wrote 130 books with NO APA content and only 43 books with APA content. Time to DECOLONIZE…

In other news, my new picture book will be out soon. Look for A HAND TO HOLD soon!

In other news, my new picture book will be out soon. Look for A HAND TO HOLD soon!

![Pageflex Persona [document: PRS0000420_00047]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1439122770i/15797434.jpg)